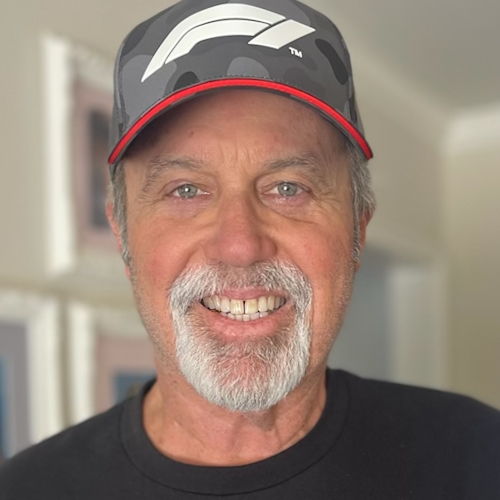

Steve’s Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) Story

A year away from retirement, Steve was looking forward to his final year as a Sociology teacher until a routine check-up revealed an alarmingly low white blood cell count.

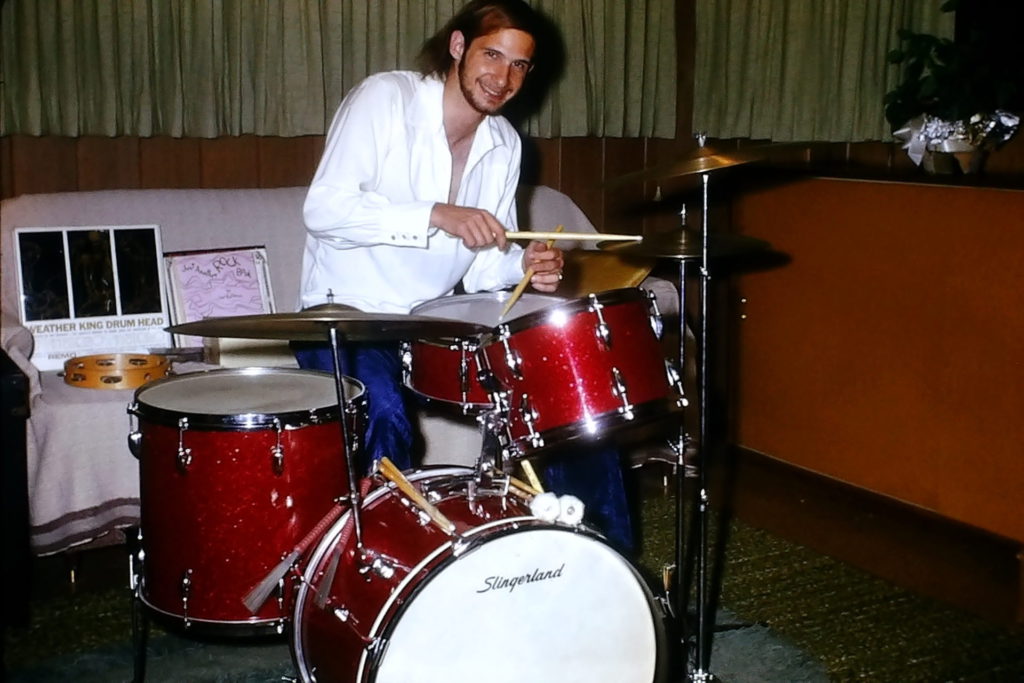

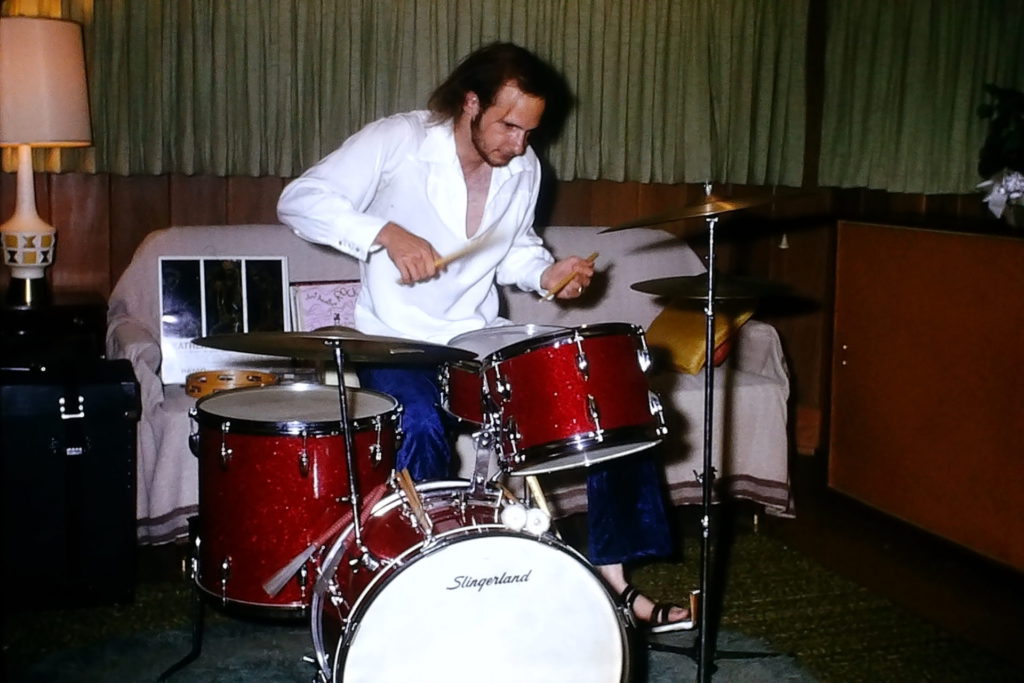

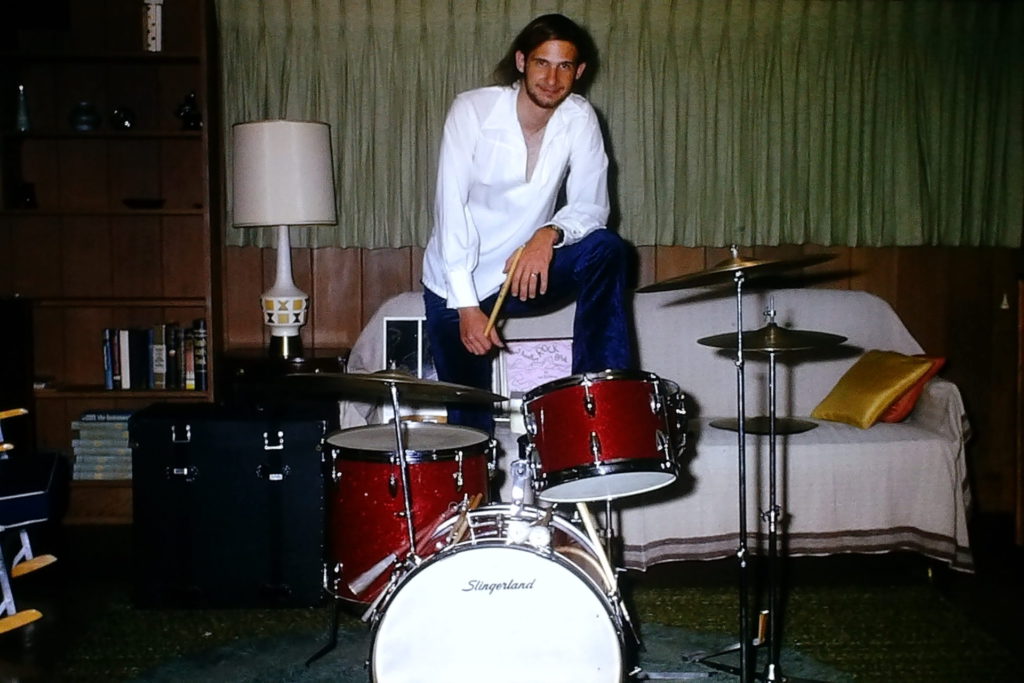

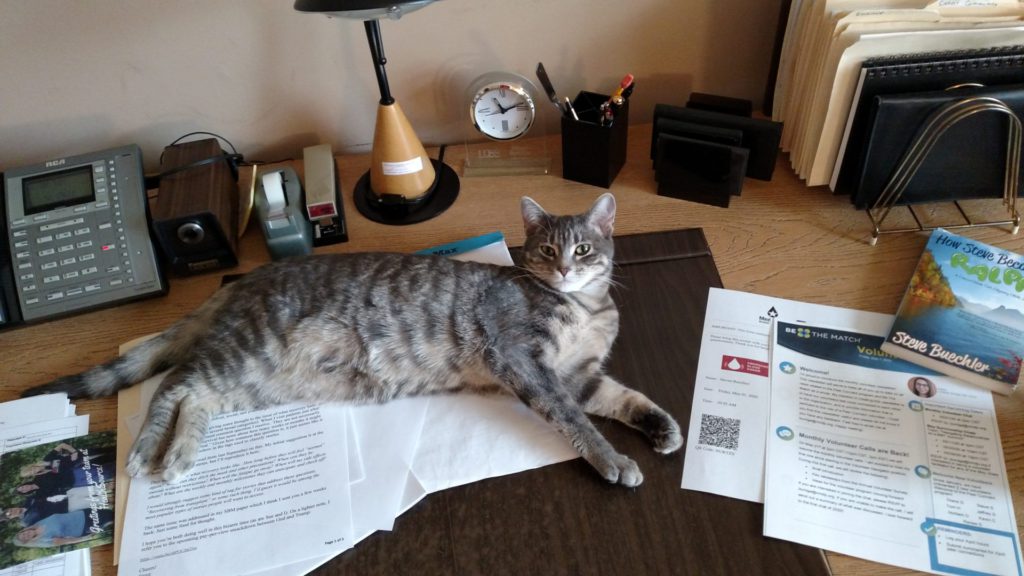

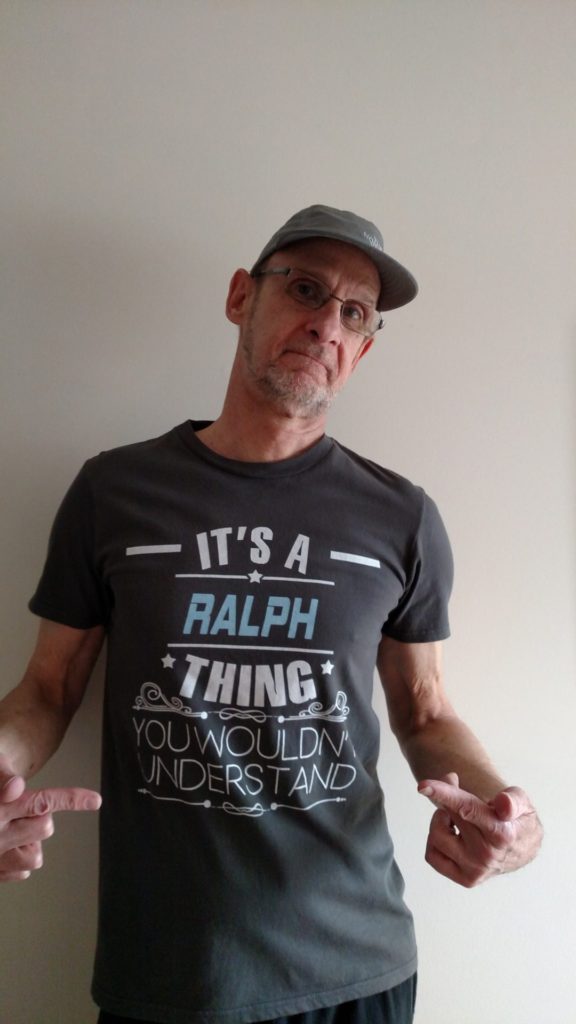

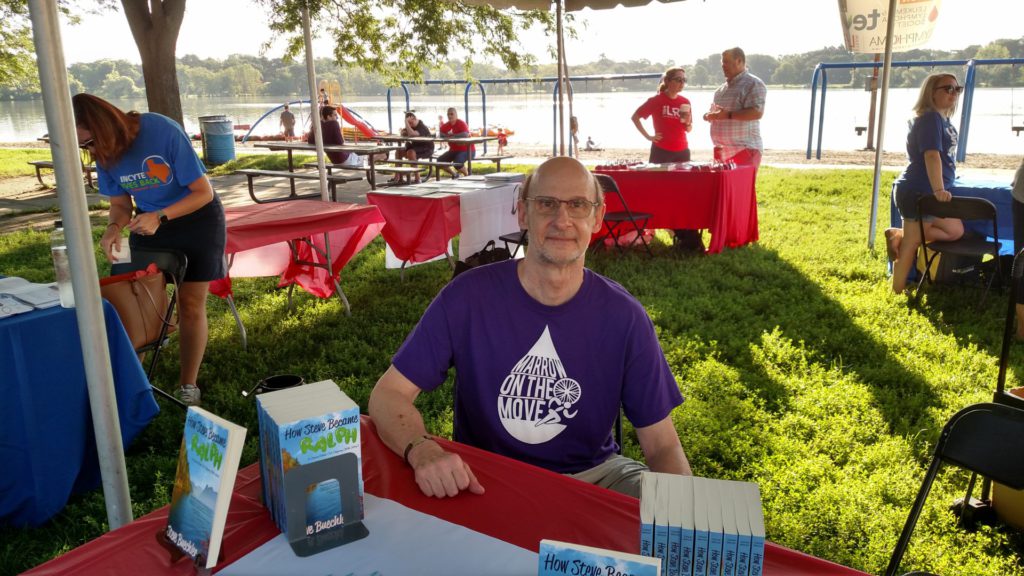

Today, Steve is a poker player, traveler, ambassador of sociology, and going on 5+ years as a volunteer in the cancer community. He also wrote a book about his experience called, “How Steve Became Ralph: A Cancer/Stem Cell Odyssey (with Jokes).”

Steve shares his story about being diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia (AML), receiving a cord blood stem cell transplant, and how mindfulness meditation yoga helped him stay positive throughout his journey.

- Name: Steve B.

- Diagnosis (DX):

- Staging: N/A

- Symptoms:

- Low white blood cell count

- Treatment:

- Chemotherapy

- 7+3 Cytarabine & idarubicin

- Pre-transplant conditioning

- Cytoxan

- Fludarabine,

- Total body irradiation

- Stem cell transplant

- Cord blood donor

- Chemotherapy

This interview has been edited for clarity. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider for treatment decisions.

- Diagnosis

- Hospital Stay

- Chemotherapy

- Starting chemotherapy

- What were the effects of 7+3 chemotherapy?

- Collaborating with doctors to find the best treatment

- How did you take precautions to avoid infection?

- How did you occupy your time during your hospital stay?

- Did anything help you cope with your diagnosis?

- Being treated like a person rather than a patient

- What was it like being without your wife during your hospital stay?

- What was returning home like?

- Stem Cell Transplant

- Life After Cancer

- Reflections

- Turning gratitude into giving back

- The importance of trusting your medical team

- What led you to write your memoir?

- The power of mindfulness and meditation

- Connecting with people through humor

- Do you think positive thinking led to your outcome?

- Discovering a common core humanity in everyone

- The value of caregivers

- What advice would you give to other cancer patients?

Diagnosis

Tell us about yourself

I need to start with my occupation and my profession, which I dearly loved because I spent about 40 years as a practicing sociologist. And although I’ve retired, I continue to be in love with my discipline because it’s a window into the world in so many different ways.

I used to urge my students – unless you plan to live on a desert island for the rest of your life, you really need to take sociology to understand the world that’s going to shape you. So you can be an active agent in that world and know how to respond and react.

We can look big picture of the world capitalist system, or we can micro-focus on 2 people interacting and everything in between. I find it to be a completely captivating perspective for looking at the world. I’m quite the ambassador for trying to recruit people into sociology when I’m not playing sociologist.

I’ve been to Minnesota’s Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness for more than 30 trips, usually a week-long, sometimes 10 days, in the wilderness where you pack everything that you’re going to need and try to survive for 10 days in a remote wilderness area. It’s a great retreat from everything having to do with the modern technological world that we live in.

I like to play poker on the side and shoot pool with a buddy of mine. My wife and I have done a number of cruises, including the Mediterranean many times. I have interests outside of being a sociologist but that’s been my core identity for most of my adult life.

How would you summarize your cancer story?

It would underscore the suddenness with which this came over me. The only time I was in a hospital before my treatment for AML was on the day I was born in Madison, Wisconsin, in 1951. I had the honor of being the 200,000th officially registered patient at Madison General Hospital, so I was destined for something, but I hadn’t been in a hospital other than to visit people for 64 years.

I landed in a hospital very quickly and I stayed for a very long time. It was all new to me. If you would ask me to define leukemia, I couldn’t have done it. I knew nothing about it, I had no exposure to it, and I had no reason to have any familiarity with it. It was a real crash course in trying to figure out what the heck was going on and where was it going to go.

I’d give a nod to the value I found in writing my story, that was one of my basic survival mechanisms. Maybe because I’m an academic and I’m comfortable with writing, but it was more than that. Telling my story for myself and for others was a way of maintaining my sanity.

A routine check-up reveals an abnormally low white blood cell count

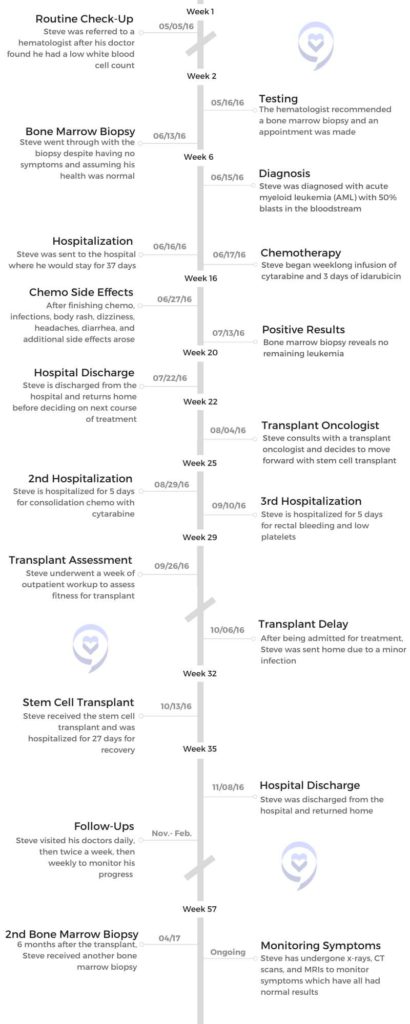

I kept the appointment at the last minute. Arguably, it may well have saved my life because they did some routine lab work and came back with very low white blood cell counts which was a red flag for my doctor.

It was the spring of 2016. Professionally, I was looking forward to one more year of teaching and then I was going to glide into a carefree retirement. But I had an annual physical schedule, which they always encourage us to do – go in and get your checkup.

Things were going so well, I almost canceled it. I thought, there’s nothing to learn here. I feel fine. I’m doing well. Why do I want to spend an afternoon going and doing this? But I kept the appointment at the last minute. Arguably, it may well have saved my life because they did some routine lab work and came back with very low white blood cell counts which was a red flag for my doctor.

He said, “I think you should go see a hematologist.” I didn’t know what a hematologist was, but they made an appointment. It was an office of Hematology/Oncology. I thought, what tree are these people barking up? I feel perfectly fine. Oncology is the furthest thing from whatever’s going on here.

Receiving a diagnosis

…he said in about a 10-minute conversation that I had acute myeloid leukemia (AML). I didn’t know what that was. I have 50% blasts in my bloodstream. I didn’t know what that was.

To humor my doctors, I met with this hematologist. They were also very concerned and said, “The next step should be getting a bone marrow biopsy to see if we can rule in or rule out what may be going on here.” I said, “If that’s what you think is appropriate, I’ll follow your recommendation. But I have no symptoms. I’m sure when we do this thing, it’s going to rule out whatever you think is going on that’s so bad.”

Call it confidence, call it naive, call it stupid, but there I am going in. It was a heck of a week. The biopsy was on a Monday afternoon. On Tuesday, I swam my normal 50 laps, saw a chiropractor, did some shopping, and I ate dinner out. Nothing could be more normal.

Wednesday morning, I played a weekly poker game with some retired guys and that afternoon I came home and my wife said, “That doctor called and wants you to call him back.” I placed the call thinking, again with this overconfidence, this is when they’re going to tell me everything is really fine.

Instead, he said in about a 10-minute conversation that I had acute myeloid leukemia (AML). I didn’t know what that was. I have 50% blasts in my bloodstream. I didn’t know what that was.

He said, “It’s imperative that you get to a hospital immediately. We’ve made an appointment for you at 9 a.m. tomorrow morning. Report to this hospital,” which happened to be across the metro from the west side of the Twin Cities where I live to the flagship hospital for my insurance.

The rest of that day is a blur. I can’t clearly remember it. I wasn’t scared or frightened or panicked. I didn’t have any conception of what was happening and how I should feel. Numbness prevailed through that evening.

I packed up some things, not knowing what to pack. They said I could expect a long hospital stay. The next morning, my wife and I drove across the metro.

»MORE: Patients share how they processed a cancer diagnosis

How did your wife react to your diagnosis?

Like me, she had no idea how to react and what this meant.

What was it like not knowing much about your diagnosis?

It’s the “Fast and Furious’”of blood cancers. It’s the deadliest of the blood cancers. I’ve heard people say, without treatment upon diagnosis, life expectancy can be measured in weeks or months if you’re lucky. It’s that fast.

My first reaction was not to go on Google and look this stuff up. Intuitively, I knew that was not a wise thing to do. In fact, throughout my early treatment, I remained naive about what this disease was and what course of treatment I could expect. In an odd way, I think that served me well until I needed to hear the hard story about what this is and make some decisions.

I was glad I didn’t know much going in because I think it would have been overwhelming. There is some research that’s been done specifically on AML patients that finds, the more they know about their prognosis, the more stress they feel and the more physical symptoms they experience. Depression sets in.

It’s not a pretty story. It’s the “Fast and Furious” of blood cancers. It’s the deadliest of the blood cancers. I’ve heard people say, without treatment upon diagnosis, life expectancy can be measured in weeks or months if you’re lucky. It’s that fast. Not learning all of those facts about AML until I needed to know them to make decisions about treatment, served me well.

Hospital Stay

Did the doctors tell you how long you’d be at the hospital?

They said weeks, but they didn’t specify much more than that.

Once I got my feet under me, I wanted to be a proactive patient and know everything from a scientific perspective. How does this disease work? How does my treatment work? I wasn’t curious about the prognosis. It was that division of labor – I want to know these things but not that thing.

Transferring to a local hospital

We drove across town, we arrived at the hospital, and we spoke with a very good oncologist. What I appreciated is he got to know us as people and not just as a potential patient.

At one point he said, “I think we could take good care of you here, but you probably want to be treated closer to home because of all the back and forth that’s going to be going on for you and all the people visiting you. I know someone across the Twin Cities, an oncologist. I can give her a call and see if she might be able to take you on as a patient.”

It took a couple of hours, but the connection was made so we drove back to a hospital much closer to town and checked in. There were some delays here and there, but that’s pretty typical in hospital admission.

Watching the medical workers was reassuring

They said I would be going to room 4-East-3. I envisioned I was going to be in someplace called room 4, in bed 3 in a barracks-style room, like an old war movie. That’s how little I knew about hospitals. It turned out I had my own room. It was fourth floor, room 3 in a very interesting hospital space where there was a central nurse’s station and about a dozen patient rooms in an oval shape around that nurses station.

I ended up liking that because I was a person that wanted to keep my door open. I wanted to see what was going on. I wanted to hear the chatter. I wanted to be connected to something larger than just my hospital room.

The more I thought about it, I realized being able to watch the nurses and the doctors go about their business in a perfectly normal way, as if this was a routine day at the office for them…I don’t know what’s happening to me. I don’t know what’s going to happen to me, but as I watch these people go about what they’re doing, they seem to know what they’re doing. I can tell they’ve done this before. I feel like I’m in good hands. It was really reassuring just to have that connection from the very first day.

I wanted to see what was going on. I wanted to hear the chatter. I wanted to be connected to something larger than just my hospital room.

Describe how your wife ended up in the hospital while you were there

I ended up in this hospital on Thursday afternoon.

Another side story that I should share because it was pretty impactful – my wife wanted to stay in my room that night to keep me company. I said, “There’s no good place here to sleep. You might as well go home.”

She got up out of one of those huge recliners that they have in hospital rooms and her right leg buckled under her and she winced in pain. We didn’t know what was going on. She limped out of the room and off she went.

The next morning, I get a call that she can’t get out of bed, the pain is so bad. She calls her sister, her sister comes over, they call 911, and they send an ambulance. An hour later, she arrives at my hospital in an ambulance at the ER.

It turns out she has a hairline fracture in her femur bone and she’s going to need surgery so she checks into my hospital and gets a room 2 floors above me. She stays there for a week. During that same week, I start my chemotherapy treatment. I checked into the hospital on Thursday, Sue checked in on Friday night.

Chemotherapy

Starting chemotherapy

I started chemotherapy, it was called 7+3. It was the standard of care at the time. A week-long infusion of cytarabine and another medication called idarubicin.

I don’t think I saw my oncologist until Saturday after I started chemo. That was when she began to lay out what was going to happen in the short term. She said, “You can expect to be here for at least a month. Because this chemotherapy is going to create a lot of side effects, you’re going to get really sick. You’re going to have infections and fevers. We know how to treat them, but they’re serious enough that we’re not going to let you leave here until you get through that process.”

From the first day or 2 that I was there, I had a short-term sense of what was going on. They were vague discussions after that. “You’re going to need more treatment, but we’ll cross that bridge when we get to it.” They really wanted me to focus on this first round of treatment because the goal is really just to stop the leukemia. Ideally to get into remission, and that’s going to buy you enough time to then consider what are my options. What comes next?

What were the effects of 7+3 chemotherapy?

I’m glad I didn’t know this at the time, but they say the chemo I had was really harsh, really brutal, and really wicked. It was nasty. They didn’t tell me that at the time. They said this is the treatment, and I said, okay, let’s do it.

My oncologist said about day 10, these things will begin to happen. I got to day 10, I’m doing fine and I’m cocky. The next day, everything just hit the fan. Colitis, E. coli infection, full body rash, headaches, fevers, diarrhea. You name it, I had it. She was exactly right, she was just off by 1 day. For about 2 and a half weeks it was awful.

Collaborating with doctors to find the best treatment

I gained a real appreciation for infectious disease doctors. These people would come in every day and say, “What are your symptoms today?” I’d rattle them off and they’d say, “This antibiotic, we can get one that’s a broader spectrum. We don’t know exactly what’s going on. Let’s switch it out for this one.” Same with the antivirals, the antifungals.

At a couple of points, it was more like a collaboration because they couldn’t figure out exactly what was causing the side effect. I remember one day saying, “I’ve been on that antifungal medication from the very first day, and somehow I think that’s complicit in some of these side effects.” And they said, “Okay, we’ll switch it out with something else.” That problem got a little better, so it was nice to see I could have a voice, I could have some input, and that on some questions, they just don’t know.

There are so many different symptoms going on that could be many different things, and people react differently to drugs. I felt like it was an experiment in itself to find what medications and what combinations would do the best to get some of these symptoms under control.

How did you take precautions to avoid infection?

They gave me medicated body wipes I’d have to use several times a day. Any possible source of the infection, I had to control it. Wearing masks long before they became fashionable with COVID, hand washing – they urge that completely. If I ever left my room without my mask, they dressed me down and said, “You can walk the halls, but you got to have that mask on.”

I learned a lot about controlling infectious diseases. Not that it prevented most of the things that got me. I also learned some of the things that got me had been living in my body my entire life. They said that’s probably true for the E. coli bacteria. After the transplant, I had a flare-up of the cytomegalovirus. They said that’s probably been in your body your entire life. If you have a functioning immune system, all that stuff is kept under control. But without it, they run rampant.

I had several visitors. They always had to be masked and keep some distance. It was a fairly spacious hospital room and they didn’t stay for a long time so that was quite manageable.

How did you occupy your time during your hospital stay?

What I appreciated the most is throughout this period I was able to leave my room and walk the halls with a mask. Later at my transplant hospital, it was more confined to quarters for 2 and a half to 3 weeks. But at my initial hospital, the first week when I was receiving chemo, I could leave my room with the chemo on an IV pole, but only walk through the cancer ward on the fourth floor and no further in case there was a spill. They knew how to deal with it, but the rest of the hospital, not so much.

To be seen, recognized, and acknowledged as a full-fledged ambulatory person and not just a sick patient in a bed really meant a lot.

Once I was done with the chemo, I explored every nook and cranny of that hospital. I was on different floors. I walked it from one end to the other. I walked out the front door to put utility bills in the mailbox up by the road. Walking was one of my basic survival strategies. It felt so good to get up and move and to see other people.

After a couple of weeks, the nurses said, “We’ve been watching you and we think you’re walking about 5 miles a day, 3 separate times per day.” That just became my routine. The best part of it was, as I walked past different staff and nurses in different parts of the hospital, they’d recognize me and I’d recognize them. We’d wave, chat, and smile and we’d share a couple of stories.

To be seen, recognized, and acknowledged as a full-fledged ambulatory person and not just a sick patient in a bed really meant a lot. I’ve told nurses that I hope they appreciate that something as simple as a smile or a wave or just some acknowledgment of recognition can mean a whole lot to a patient when they’re vulnerable.

Did anything help you cope with your diagnosis?

Right at the top of the list would be the combination of practicing mindfulness meditation and yoga. The really serendipitous thing is about 2 months before my diagnosis, I received a flyer promoting a community education class on these topics. I thought, I’ve dabbled around with meditation and yoga and I’ve never done it seriously. I’m not very good at it, but I’m going to take this class. It was a time in my life when I really needed to incorporate that into my daily activity.

About 8 weeks before my diagnosis, not knowing it was coming, I was meditating, I was doing yoga. One of the gurus of this approach, Jon Kabat-Zinn, has said we can change the way our brains are wired in as little as 8 weeks of systematic practice. It was about 8 weeks before my diagnosis hit.

For most of my life, I could be mistaken for a chronically anxious, anal-retentive, obsessive-compulsive control freak. You would think cancer would throw me through the roof and it was almost the opposite.

I know a lot about staying in the moment, rhythmic breathing, staying in touch with my body, yoga, and the body scan. From the very first night in the hospital when things finally quieted down and Sue left and the lights go out, it was like, if the demons are ever going to come it’s at night. I did a body scan and I started with my toes, my ankles, and my feet. By the time I got to my torso, 15 minutes later, I fell asleep.

I did that every night in the hospital and I never lost any sleep to anxiety. The nurses came in at all hours and people came in for medication checks and vital signs, so you can’t sleep in a hospital anyway. But it was never from fear or anxiety because I had this powerful tool to deal with it.

Being treated like a person rather than a patient

I was deliberately a proactive patient. I sought out those relationships with nurses and when you’re there for 37 days, you have a chance to do that. They got to know me as a real person, and that was tremendously important for all the reasons we’ve just discussed.

Every couple of days I’d be sent down to imaging for an x-ray or a CT scan and an orderly would show up at my door with a wheelchair ready to take me to imaging. I would say, “I’m walking 5 miles a day in the hospital. I know where imaging is just as well as you, so I’m going to walk.” Sometimes they would say, okay. Other times they would force me to get in a wheelchair. I really resented that because I was being treated as a generic patient and not the individual that I am.

When I got to the imaging, [it was] kind of the same thing with the techs. I’m the 93rd person they’re doing today so they treat me very generically. It was very alienating till I got back to my room and my familiar nurses. It was like, okay, now this is home. You’re my people. We’re back on track.

What was it like being without your wife during your hospital stay?

She was in the hospital with me for the first week, but then she went to a transitional care unit (TCU) for a month of rehab. We learned how to do FaceTime and various kinds of screen-sharing things, but it was very weird and very artificial. No one looks good on a little tiny phone screen. Some of the communication was kind of minimal, but we both had our own struggles to bear.

She has a sister who lived in town, and she was a crucial go-between. She would take things back and forth, bring the mail to me, and the newspapers to her. Having someone like that is a lifeline to keep our lives connected. That helped a lot.

What was returning home like?

It was a whole month after [Sue] left for her TCU and I went through my remaining month of hospitalization. After 5 and a half weeks, she came home 1 day before I did. Our home had been unoccupied for roughly 5 weeks. Open the refrigerator and it was like a petri dish, so we had to clean that out.

Gradually we got back to a little bit of normality as I had to figure out what’s the next stage of treatment and where is this eventually going to go. She still had a fairly long recovery, but at least she could be home and maneuver a lot of the time. We shook our heads like no one was going to believe this happened to us.

At the same time, there was that little storm that hit about 3 weeks into my hospital stay. That was an interesting thing to learn from my neighbors. One night they emailed me photos of 2 60-foot trees that fell down on our house while it was unoccupied. I was dealing with a tree service, contractors, and roofers remotely, trying to get the trees out of there and the house repaired. That all took care of itself.

In my family, there was an old saying that bad things happen in threes – my cancer, Sue’s broken leg, trees falling on the house. It should be clear sailing from here out. Not exactly, but it helped to think that way.

Stem Cell Transplant

Deciding the next course of treatment

Eventually, I decided if I went the chemo route and it didn’t work out, I would always regret not trying the transplant. And if I did the transplant and it didn’t work out, it would at least feel like I gave it my best shot, so I really committed to the transplant.

What triggered my release from the hospital was my immune system came back up. 4 weeks in, they did a bone marrow biopsy and they said there was no cancer. Huge achievement, but this is a cancer that always comes back so we’re on to the next step.

In a nutshell, they said, “We need to wait for the genetic and molecular analysis of your cancer, and that will put you in either a fairly favorable risk profile or an adverse risk profile. If it’s the former, you’ll probably get by with more chemo. If it’s the latter, you’ll probably need a stem cell transplant.” I thought, here’s a fork in the road. The decision will make itself.

When the results came back, they said, “You’re actually in an intermediate category. You’re not in either one, so there’s no clear path forward. We’re going to send you to the University of Minnesota Medical Center where they do transplants.”

I had a 3-hour tag team meeting with nurses, social workers, and a transplant oncologist. Thankfully, she just laid it on the line. She said “You need more treatment. You need consolidation after your induction treatment. Chemotherapy has a 5-year survival rate of 33%, but a lot of patients can’t tolerate how toxic it is so they have to stop before it’s over.” My thought was, I hope you have something better than that.

They said the transplant has a 5-year survival rate of 50% but you have to first survive a 15 to 20% mortality rate from the procedure itself because it’s so brutal. That was like Russian roulette. Six chambers, one bullet. She said, “If you want the transplant, I’m happy to do it. Otherwise, I’ll refer you to someone else if you want to do the chemotherapy route.”

I went back to my original oncologist and laid all this out. She reiterated the risks and potential benefits of both options, but she wouldn’t give a recommendation. Bless her, my wife Sue said to my oncologist, “If Steve was your husband, what would you want him to do?” And she said, “Get a transplant immediately.” That reinforced the notion of transplant.

I got second opinions from doctors at the Mayo Clinic. Eventually, I decided if I went the chemo route and it didn’t work out, I would always regret not trying the transplant. And if I did the transplant and it didn’t work out, it would at least feel like I gave it my best shot, so I really committed to the transplant.

Joining a clinical trial for stem cell transplants

Then we needed a donor. They tested my one and only sibling, my brother. He was a half-match, which is workable but not ideal. The doctor said we could consider umbilical cord blood as a donor source. I was like, “Am I in a science fiction movie?” I’d never heard of that. They reassured me it was a real option. Again, I said, “Okay, you’re the expert.”

Which is better? They said, “We don’t know, but we have a clinical trial to find that out and if you want to join the trial, you can do so.” I read a 22-page consent form, asked some questions, and agreed to the study.

I was randomly assigned to the cord blood arm of the study rather than the half-matched brother arm of the study. My brother was off the hook and at that point, I knew I would be headed for a transplant.

I knew the facility, I knew the donor category, and it was a matter of staying in remission. I had a week of consolidation chemotherapy to keep me in remission until we could get to the transplant.

Delaying the transplant

I went through a workup and tested all my vital organs, [which] I passed. I checked in for the transplant at a different hospital in early October. The day I checked in, I happened to mention to the nurse I had some symptoms like a cold or a mild infection. She said, “Let me get a doctor in here.”

This doctor comes in, and he says, “I’m going to cancel your transplant. You have an infection and we want you to get over that infection before we do the transplant.” I must have looked really disappointed because he told this story that many years ago, they admitted someone with my symptoms, and administered pre-transplant chemotherapy. The patient became immunocompromised, developed pneumonia, and died before he could get to transplant. I said, “Okay, I like your logic.”

A week later, my infection cleared up. I came back and checked in. It started on, what they call, day minus 7. One week before the transplant, you have a countdown to the transplant date.

Describe your stem cell transplant

…you have this waiting game of, will one of my donors graft? How will I respond to the new immunosuppression? That begins a whole new chapter in the saga.

They administered cytotoxin, which I later looked up and realized it’s actually derived from the mustard gas used in chemical warfare in World War 1. Along with another medication called fludarabine and total body irradiation. That’s to wipe everything clean – wipe out my bone marrow, wipe out any residual leukemia, and prepare my body to accept the donor cells.

Transplant day came. Talk about a non-event after everything that you go through. A stem cell transplant just means a nurse brings in a bag or 2 of blood, hangs it on an IV pole, attaches a tube, and flips a switch. That’s it. Once you get to that point, it’s the simplest thing in the world.

Then you have this waiting game of, will one of my donors graft? How will I respond to the new immunosuppression? That begins a whole new chapter in the saga.

What advice would you give someone considering a stem cell transplant?

Read and try to understand as much of the write-up that they give you. Ask as many questions as you can.

In my case, it was a relatively easy decision because I was going to have one of these two treatments anyway. I could have chosen and said I want my brother or I want the cord blood, but by going into this study, I left the decision up to their randomization process. Maybe I contributed a little bit to the progress of science but it was such an even trade-off that I couldn’t find a basis for making a decision myself.

Both paths had different strengths and weaknesses. With cord blood, you’re a little less likely to have graft versus host disease because the cells are naive. They’ve never lived in another body but it can take longer to engraft with a half-matched donor. As someone once said, when his cells get in my body, half of them are going to recognize my body as foreign and there’s a much greater chance of graft versus host disease, but that tends to be earlier engraft.

It was a real toss-up. If I’d had a clear indication that either was better, I would have gone for it. Since I didn’t, I said put me in the trial. It was a very passive trial. They followed my outcome along with several hundred other people and ironically they concluded that the half-matched donor was marginally better than the cord blood. But that’s a generalization. I was one person and my cord blood transplant worked tremendously. It couldn’t have been better. I got all the benefits and none of the downsides of cord blood transplants.

Life After Cancer

Did you not have any side effects from the transplant?

Only if you overlook the first 3 months after the transplant. I was in the hospital for 27 days one week before transplant, and then 2 and a half weeks after transplant. They let me go earlier than expected, but I was doing reasonably well so I came home.

I needed a caregiver with me for at least the first 100 days, preferably longer than that. Since Sue wasn’t entirely able to fulfill that role because of her own medical issues, I recruited a 5-week rotation. My brother came and stayed with me for a week, then an old college friend, then my brother came back, then my college friend’s wife, then my brother came back.

For 5-weeks, someone lived in our house 24/7 in case something happened that needed a quick response. None of that really happened, but they drove me back to the clinic every day for the first month.

It always started with a blood draw. They’d say, “Your platelets are a little low. You need some red blood. Today you’ll be here for 4 or 6 hours to top off your fluids.” Gradually those things became less frequent.

»MORE: Cancer patients share their treatment side effects

Post-transplant symptoms and treatment

The first month, I had unimaginable fatigue from the transplant and the engraftment process and the residual effects of the medication, a fair amount of nausea, bone aches as the engraftment happened and just generally feeling out of sorts.

I was on anti-rejection medication that was suppressing my immune system so the engraftment could take place. That left me open to all kinds of other infections. They talk about getting through the first 100 days, and I didn’t fully appreciate what that meant.

At that appointment 100 days out, they said, “We’re going to begin to taper the anti-rejection medication, but we’re going to do it very slowly over a 3-month period so that your body can slowly ramp up its own immune system. We don’t do it so quickly that graft versus host disease rears its ugly head.”

I likened it to, I’m old enough to learn to drive on a stick shift, and you have to put the clutch down and the accelerator in a certain pattern. That’s exactly what they did. I still had a lot of side effects but nothing catastrophic. It worked out very nicely.

Did your donors engraft after the transplant?

Two days after I left the hospital, I came back for my first post-transplant bone marrow biopsy. That’s when they discovered one of my 2 cord blood donors was 99% engrafted. That was really early for a cord blood procedure.

Before the transplant, I had this odd sensation that my life depended on – I thought of them as 2 kids, really mothers, who donated umbilical cords. I knew that one of them was a baby boy and one of them was a baby girl. I wanted to be on better terms with them, so I named them. I named the boy Ralph and the girl Gwen.

They could determine 3 weeks after the transplant that Ralph had engrafted 99%. Gwen had kind of faded away, which is typically what happens. I felt bad using up 2 donors, but they don’t know ahead of time which one might engraft, and the protocol called for 2 so we did that.

My oncologist later said Gwen, even though she disappeared, may have played a role because for a couple of weeks, they were both circulating in my blood system and they were competing for dominance. Gwen was like a sparring partner that toughened Ralph up and got him to be more effective in battling an infection. Then she went on her way and Ralph made a home for himself in my body.

The first year after the transplant

At the 6-month appointment, my transplant oncologist called me a statistical outlier because the likelihood of early remission, full engraftment, and no graft versus host disease happening together is less than a 10% probability.

At the 6-month mark, I was off the anti-rejection medication. I was starting to feel human again. At 9 months, I was invited to give a keynote address for a fundraiser for my transplant unit in front of 400 people on a sun-kissed July morning in an urban lake. It was really sweet.

One year out, we got our childhood vaccinations redone from dead sources. Two years out, we got our childhood vaccinations from live sources, and by that point, it was obvious I was in the clear and have been ever since.

At the 6-month appointment, my transplant oncologist called me a statistical outlier because the likelihood of early remission, full engraftment, and no graft versus host disease happening together is less than a 10% probability. The numbers are impressive, but when she said this is as good as it gets, that was the stamp of approval that I’d come through this thing. At that 6-month mark, I was able to accept the fact that I’d really made it and I was going to be around for a while

From cancer patient to cancer survivor

That was a crucial moment. That was the day I changed my understanding of my identity from a cancer patient to a cancer survivor.

It still felt like there was a shoe up there that could fall at any time.

At that 6-month appointment, not only did everything look good, but I said to this oncologist I’d seen daily, then 3 times a week, then twice a week, then once a week, and then once every 2 weeks, “When should I see you again?” Her response was, “Maybe 6 months.” That was unnerving. It’s like attachment disorder. You’re letting me go. You’re cutting me loose. But she said, “Steve, it’s a good thing when you don’t need to see your doctor.”

That was a crucial moment. That was the day I changed my understanding of my identity from a cancer patient to a cancer survivor. There could always be a relapse, all kinds of things could happen. This is the time that demarcates having cancer and treatment and getting beyond it. I tried to capture it in some writing I did, and the phrase I came up with was I was experiencing serene euphoria. I didn’t want to shout from the rooftops, I just wanted to quietly let this feeling wash over me, take it in, and embrace it.

Shortly thereafter, I began thinking I need to find ways to give back. Therein I launched what is now a 5-and-a-half-year volunteer career. I’ll never repay the debt to the people who saved my life, but it’s a lot of fun trying and it’s very gratifying to do the things I’m doing in the cancer community.

How did your doctor’s positive words make you feel?

It was a great relief. I joke that I’d always been pretty good at taking tests as an academic. This was like a test, but unlike anything, I’d ever been through. Feeling incredibly fortunate, incredibly lucky.

I’ve written a bit about, who gets cancer, why they get it, and who survives. You can point to all kinds of reasons that probabilistically make a certain outcome more likely, but I’m convinced there’s a certain element of random variation and luck in these outcomes. I’ve learned a lot about that.

Frankly, as a poker player, I think there’s a lot of poker wisdom that applies to the decisions you make when you’re going through treatment. As in poker, so in medicine.

You can make a good decision with the information you have at the time and you can still get a bad outcome. That doesn’t mean it was the wrong decision. It just means you had incomplete, imperfect information. Things are constantly changing, so don’t beat yourself up if the outcome isn’t what you hope for, you still may have made the right decision. That was helpful to think about it that way.

Reflections

Turning gratitude into giving back

There’s a depth of gratitude, that I never experienced before. People always say to be grateful. That’s a great thing. That’s a mentally healthy thing to do. I understood it when I had this to be grateful for. That’s a big part of what fueled the work I’ve done since.

It started with these peer connect programs where, as a transplant survivor, I would be linked with newly diagnosed patients to talk to them on the phone. For 2 and a half years until COVID struck, I did this back at my transplant hospital.

I’d walk into patient rooms and say, “I’m a volunteer.” They go, “Yeah, yeah, what now?” I’d say, “But I’m a transplant survivor.” Suddenly they would perk up. They would sit up straight, they would invite me in, and we’d have these incredibly personal conversations between 2 complete strangers. But we shared the bond of transplant. That’s quite a bond to share.

There’s a depth of gratitude, that I never experienced before. People always say to be grateful…I understood it when I had this to be grateful for.

The importance of trusting your medical team

Be as well-informed as you possibly can be. Be a proactive patient. Trust your medical team if they’re trustworthy. And if they’re not, if you don’t have a comfortable relationship with your medical team, think about whether you need to make a change because that’s really critical.

All kinds of sources of information are out there, but no one knows you the way your own medical team does in terms of the specifics of your disease and your mutations. You really have to put your fate in their hands and hopefully, you have good hands to put them in. I certainly did.

What led you to write your memoir?

I found great benefits from writing my story. I started sending out emails to people. I wrote 65 very long emails to a group of roughly 100 people over 18 months and turned them into a memoir. That was never my plan. Six years later, I’m still writing quarterly updates. I’m working on another book, so writing is obviously therapy for me.

It started by wanting to keep people informed, but I quickly realized needing to tell a coherent story of what I’m going through requires me to understand it better than I have up to this point. It’s kind of like the old adage – if you really want to learn something, teach it. That’s what this felt like. If I’m going to tell my email recipients what’s going on, I need to get it straight myself.

The social scientific part of me enjoyed that process of constructing a narrative that made sense. Initially, so they knew what was going on, but [then I] realized this is therapeutic for me. I’m a sense-maker. If I can make sense of something, even if it’s bad, I can deal with it. If it doesn’t make sense to me, then I’m at loose ends.

The power of mindfulness and meditation

If you can just live in the moment, you’re going to have as rich a life as you possibly can have and the outcome will be what the outcome will be.

I would encourage people to incorporate mindfulness and all its different manifestations. One thing I learned from mindfulness had to do with what’s called scanxiety. You have an upcoming test or scan and people get understandably anxious.

It occurred to me that if I get all bent out of shape because I have a test or a scan coming up in 2 weeks and it turns out fine, I just wasted 2 weeks of my life getting tied up in knots over something that hasn’t even happened yet, which is really odd if you think about it. If it turns out that it’s bad, that proves to be anxious doesn’t prevent a bad outcome. So there’s no reason to be anxious if you can logically train your mind to think that way.

I got pretty good at doing that. People are bedeviled by fear and anxiety. I’m not implying in any way it’s a simple thing, but to whatever extent you can live in the moment and let each moment come and have some confidence that you and your medical team will know how to deal with that moment if and when it comes…It doesn’t guarantee that all is going to go well, but it’s a much happier way to pass the time.

If you can just live in the moment, you’re going to have as rich a life as you possibly can have and the outcome will be what the outcome will be. It’s like a poker hand. You might win, you might lose. You do everything right and have a bad outcome. You might be lucky and have a good outcome, but that’s in the future and you can’t know the future. So don’t get into a wrestling match with things that haven’t even happened yet. Keep your feet anchored in the present moment.

Everything that goes along with mindfulness meditation and yoga is a really good way of embodying that. As you work through the yoga poses and the breathing, it really keeps you centered. I don’t want to proselytize because that’s just not for some people, but I’ve heard a remarkable number of patients in the cancer community endorse the notion of mindfulness meditation and yoga.

Connecting with people through humor

I hung onto my sense of humor relentlessly. That was really important to me, and that’s not a joke. Every email I sent out, I ended with a joke because I wanted to lighten the burden of these sometimes very dire stories I was telling people.

Humor kept me connected to people. There were people who I’d known on and off throughout my life. They didn’t know how to relate to me as a cancer patient, but they knew they could share a joke with me and that maintained our connection. Humor can be a very serious survival mechanism.

Do you think positive thinking led to your outcome?

People gave me credit for my positive thinking and that’s why I had a good outcome. I never liked that. If I hadn’t made it, would they say I wasn’t positive enough? I think positive thinking is fine if the patient can find their way to a version of it that works for them. But if it’s other people telling you you have to be positive, what they’re really saying is, you can’t have any negative emotions. You can’t have down days, you can’t express this or that, and that’s not the way it goes.

Cancer patients need as much agency as they can possibly find. They don’t need to be told by other people how to react. So positive thinking is fine if you find your way to it and it works for you, but not as a gospel that gets hammered into people’s heads.

I’ll never know if all those strategies I employed contributed to my positive medical outcome. I do know they allowed me to live as fully, through all these days and times and processes, as I possibly could. That sustained me.

Cancer patients need as much agency as they can possibly find. They don’t need to be told by other people how to react.

Discovering a common core humanity in everyone

I witnessed a degree of resilience in a broader span of people than I would have imagined. It’s striking how tough people can be in these circumstances. Many of the people that I talk with, especially in the transplant community, had a much tougher ride than I did. Yet, their ability to find their own coping mechanisms and persist is really quite remarkable.

This may sound corny, but I’ve seen a lot of people at their worst and it’s attuned me to the fact that there is a common core humanity. It doesn’t matter if the person undergoing this process is male or female or an ethnicity or what have you. At some fundamental level, we’re all pretty similar and I didn’t quite fully appreciate that until this process.

Sociologists talk about how in social life we present a certain self to others. We’re like actors conveying through impression management a certain sense of who we are. That’s pretty hard to do in a hospital bed when you’ve got all these things going on.

I’ve had people in conversations where the guy says, “I really like talking to you, but I got to go throw up. Can you hang on till I’m done?” He goes and throws up and comes back and we continue our conversation. Well, there’s not much presentation of self going on. You’re down to the core sort of reality of who people are. It kindled in me a tremendous amount of empathy that I hadn’t quite found, along with gratitude, and the ability to empathize with what people go through.

I have to put in a pitch for a short video called Empathy by the Cleveland Clinic. For about 4.5 minutes, a camera pans through a hospital, these people are walking by, and you can’t tell from their facial expressions what’s going on. There’s a little caption underneath that says, “Just learned his condition is terminal.” The next person comes by and it says, “Found out his mother’s going to survive.” You see these people from the outside and it’s not clear what’s going on, but it could be a million things. It’s a powerful video.

This may sound corny, but I’ve seen a lot of people at their worst and it’s attuned me to the fact that there is a common core humanity. It doesn’t matter if the person undergoing this process is male or female or an ethnicity or what have you. At some fundamental level, we’re all pretty similar and I didn’t quite fully appreciate that until this process.

That reinforced this empathy I was finding from the range of people I was talking to, the diversity of those people. Yet, underneath that diversity, there’s a small core element of humanity that shows up in everyone. It was very moving.

The value of caregivers

Caregivers oftentimes absorb more stress than patients themselves, so kudos to all the caregivers out there. The importance of caregiving needs to be acknowledged and recognized.

What advice would you give to other cancer patients?

For patients, they say it doesn’t build character as much as it reveals character. It doesn’t change you into a totally different person, but it calls for the kind of person you are. Many people have learned coping strategies, survival mechanisms, and resilience strategies. Something like this really puts them all to the test.

So if you can find those, if you can marshal those, if you can bring them to the fore, surround yourself with a supportive community, get yourself a good medical team, try and find a reasonably optimistic and hopeful stance and maintain that stance through whatever coping strategies work for you, being as physically active as possible, doing mindfulness meditation yoga, being a proactive patient, don’t be a dependent variable, be part of what’s going on, have a belief system you can fall back on…

For a lot of people, that’s religion. That’s not especially my approach. I had a scientific secular worldview that was filled with curiosity and interest and wanting to understand how things work. When my doctors would explain it to me, then it was like, now I understand where I’m at and where I’m going.

Writing your story in whatever form works for you. I’m doing a writing workshop with the Leukemia Society right now and people are having some incredible insights writing and sharing it with one another. It’s a powerful tool.

I could plug a book by a doctor named Annie Brewster called The Healing Power of Storytelling. It’s the best thing I’ve ever read on how telling your story can help maintain your humanity in the face of whatever life throws at you.

Acute Myeloid Leukemia Stories

Russ D., Acute Myelomonocytic Leukemia (AMML), with NPM1 Mutation

Symptoms:Flu‑like symptoms, profound fatigue, blood pressure drop, shortness of breath

Treatments:Chemotherapy, clinical trial (menin inhibitor)

Shelley G., Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) with NPM1 Mutation

Symptoms: Fatigue, rapid heartbeat, shortness of breath, low blood counts

Treatments: Chemotherapy, clinical trial, stem cell transplant

Joseph A., Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML)

Symptoms: Suspicious leg fatigue while cycling, chest pains due to blood clot in lung

Treatments: Chemotherapy, clinical trial (targeted therapy, menin inhibitor), stem cell transplant

Mackenzie P., Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML)

Symptoms: Shortness of breath, passing out, getting sick easily, bleeding and bruising quickly

Treatments: Chemotherapy (induction and maintenance chemotherapy), stem cell transplant, clinical trials

One reply on “Steve’s Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) Story”

Steve B , thank you so much for your story, inspiring. My husband who is 66, good health was just diagnosed 12 days ago with AML FLT3. He had no symptoms other than runny nose and tired. He went to doctor, who thought he was having reaction to allergy medicine he took to get rid of runny nose. Blood test latter, white count of 83. We are still reeling. Transferred 2nd day to cancer hospital, bone marrow test, 4th day started 7+3 therapies.