Renée’s Acute Myeloid Leukemia Story

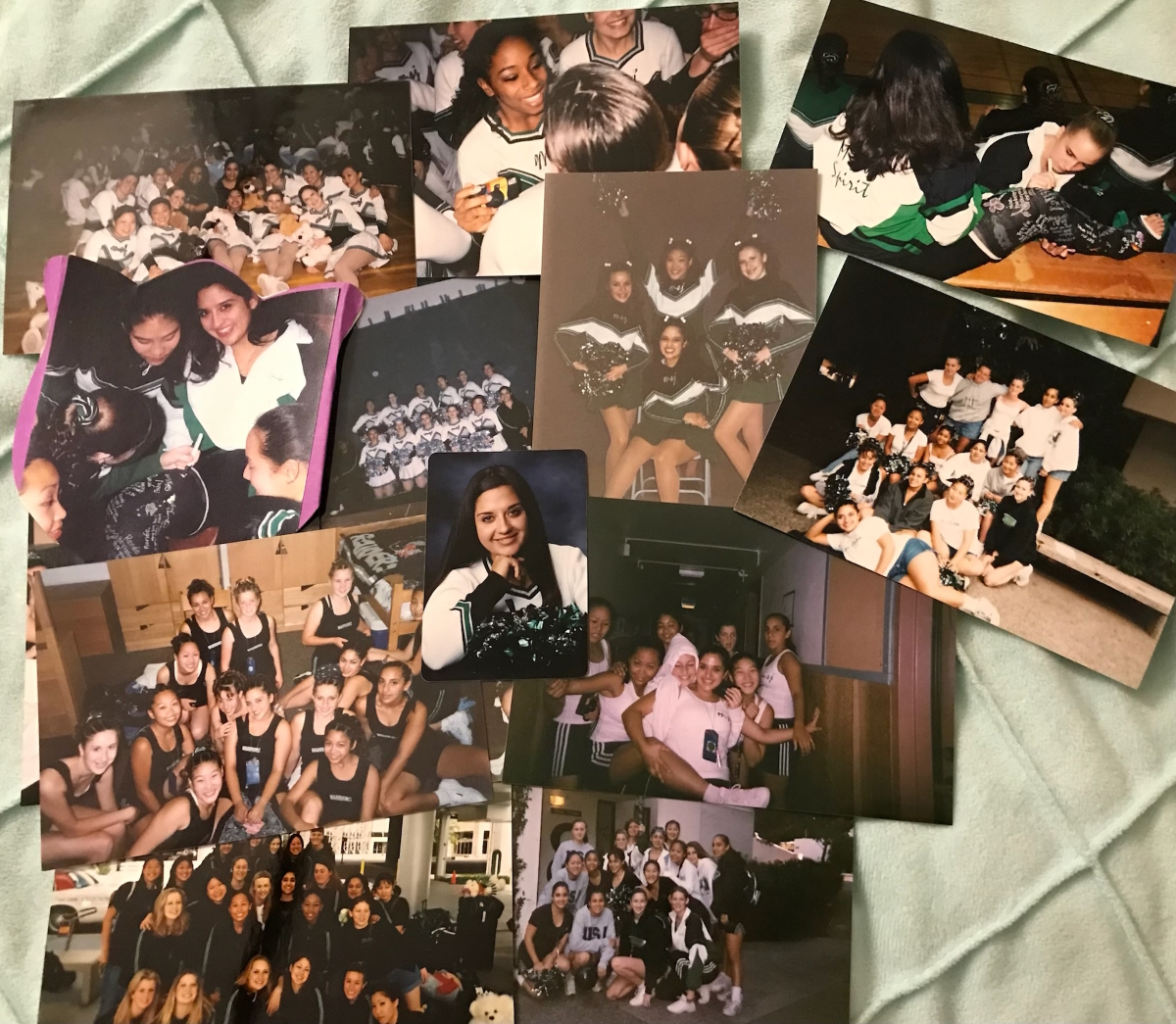

Renée was 18 when she started noticing bruises all over her body. At first, she thought the bruising was normal because she was a cheerleader and dancer.

After she had her wisdom teeth removed, her health rapidly declined, prompting her mom to bring her to the hospital.

She shares her story of finding out she had an aggressive type of cancer, being told she won’t be able to have kids, and the miraculous surprise of finding out she was pregnant.

This interview has been edited for clarity. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider for treatment decisions.

- Name: Renée F.

- Diagnosis:

- Acute myeloid leukemia (AML)

- Initial Symptoms:

- Bruising

- Treatment:

- Chemotherapy

- Radiation

- Allogeneic bone marrow transplant

All I was holding on to was trying to keep it together because these little, itty bitty pediatric kids are looking up to me.

‘We don’t know what’s going on just yet, but because you’re 18, we need to ask you if you have a DNR.’ I panicked… and immediately signed my rights to my parents. Then the rest was a big blur.

Introduction

I’m from California. I love the ocean. I love hiking. I’m very artistic and creative, and I like to find careers that allow me to utilize that creativity. I was a preschool teacher for many, many years.

I’m a single mom. I’m kind of obsessed with my kid. My world revolves around her. [It’s] really special that I get to relive all my favorite things from my childhood with my daughter.

She is incredible and very smart. She’s got an old heart, an old soul, and she’s determined to be a doctor or a surgeon so we’re working on that. And we have two cats.

I can’t control how this disease ended up in me, but I can control what I’m going to do now.

Pre-diagnosis

What were your first symptoms?

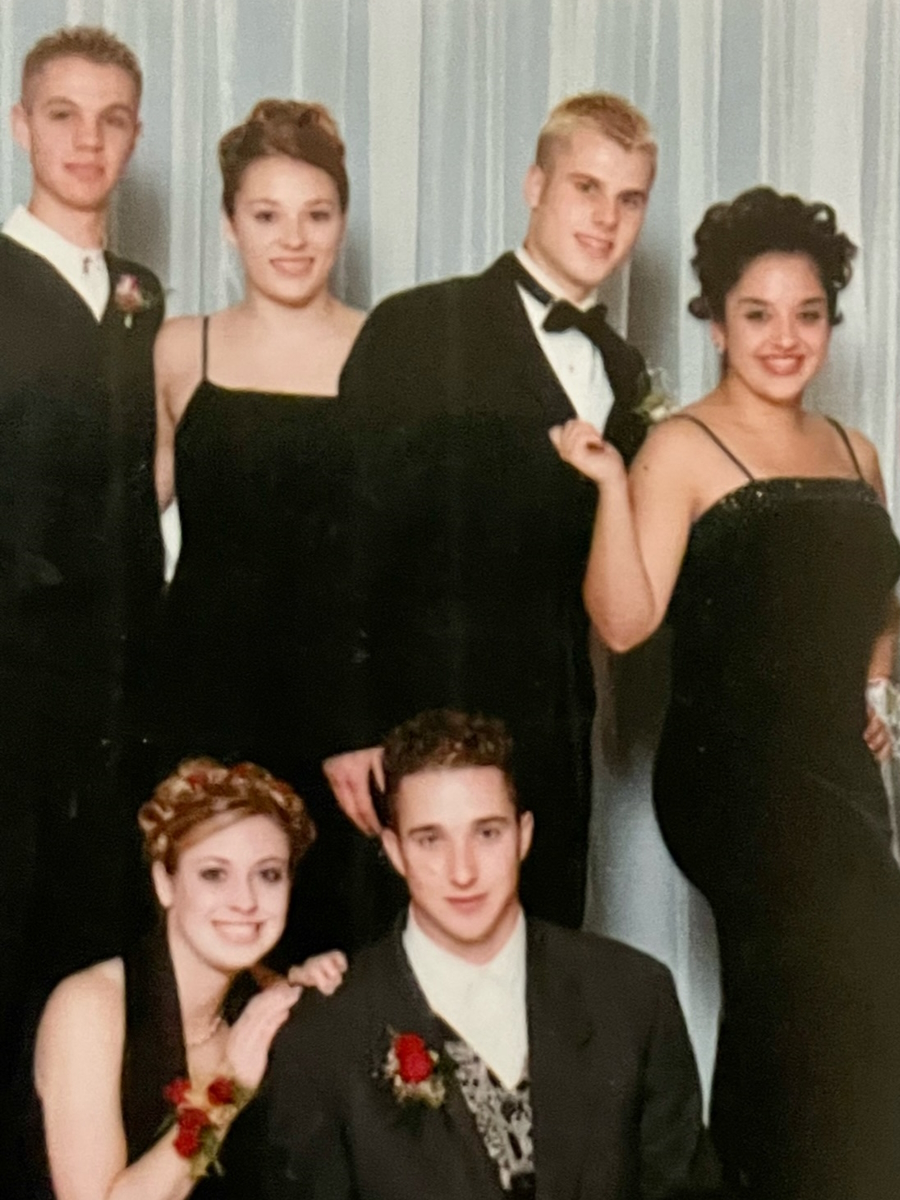

I was a senior in high school. I was a cheerleader and a dancer so I was covered in bruises all the time and always achy. That was normal for cheerleading.

I got my wisdom teeth pulled. Surgery [went] perfectly fine but after, things went downhill really, really fast.

My mom, who insisted that there was something wrong, rushed me to the hospital. They did some blood work and told us, “Don’t go very far. You’re not being admitted yet, but we’re going to get the results fairly soon so just stay close by.”

[After] maybe 20 minutes, the hospital staff was running down the hallway with the wheelchair, yelling my name. They found me and my mom and said, “You need to come with us. We need to take you back to do more testing, but we need to get you back to the hospital.”

They brought me in and said, “We don’t know what’s going on just yet, but because you’re 18, we need to ask you if you have a DNR.” I said, “I don’t have my driver’s license yet.” She said, “That’s not what that means,” and explained to me what a DNR was.

Because I was 18 and really sick, I had two options: (1) sign off my rights to my parents, be completely admitted to the hospital with unknown circumstances, and let my family make decisions and choices on my behalf because I was going downhill very quickly; or (2) make my own decisions and sign a DNR.

I panicked, didn’t really know how to respond to that, and immediately signed my rights to my parents. Then the rest was a big blur.

They told me that I had a less than 25% chance of making it through the night, let alone the week… I hadn’t even gotten my driver’s license or my high school diploma yet and everything was just ripped away.

Everything quickly went downhill

I was diagnosed [on] May 27, 2002. I had my wisdom teeth pulled prior to my diagnosis. It went downhill really quickly.

I’m trying to think back: when did I first really notice symptoms? When I was 16, I broke my fibula. I had a spiral fracture. Could it have been from then? I don’t know.

I don’t know how I ended up with this. I went to a very small Catholic school in Fremont. [Out of] 32 kids in my elementary school class, four classmates including myself were diagnosed with a form of cancer — two with breast cancer, two with leukemia, and two required bone marrow transplants. I was number 2. All before we were 35.

It makes your head spin and at the same time, you get nowhere. I can’t control how this disease ended up in me, but I can control what I’m going to do now.

In my mind, there was no other option. It was going to work, I’ll be damned.

Diagnosis

From that moment on, I spent about seven months in the hospital. I was in [the] ICU, hanging to life. All my friends from high school were called. All the teachers. Everybody just took off and flooded the hospital.

At the time of my diagnosis, they told me that I had a less than 25% chance of making it through the night, let alone the week. I was going to need two platelet transfusions and two blood transfusions right then and there just to get me stabilized.

If I made it through the week, there was a 50% chance the treatments would work [and] if they did, there would be a 50% chance of developing [a] secondary cancer. The treatments would cause me to be infertile because there is not enough time or science to consider any fertility-saving options.

I hadn’t even gotten my driver’s license or my high school diploma yet and everything was just ripped away.

I’m a very religious person so it was a very religiously-powered, emotional roller coaster. I clung to my faith, used music as therapy, and practiced mindset mindfulness.

How did you process the diagnosis as an 18-year-old?

Lucky for me, I’m very stubborn. Being the third out of four girls, you got that middle child syndrome so you want to be heard, you want to be seen.

At that time, I was at a really low point in my life. My parents had gone through a really bad divorce and it was just really hitting me hard. When you’re a teenager, struggling with your emotional wellness and where you fit in this big, crazy world, that’s a lot to carry on your shoulders. Then add to it something that you have no control over, that’s fully taking over your life, and you just scream for control.

In my mind, there was no other option. It was going to work, I’ll be damned. It’s going to work. That was just the mindset.

I remember telling people, “I can’t have you crying in front of me right now because I’m going to lose it. If you cry, that’s fine. Just do it outside. I need to stay stable as best as I can.”

I’m a very religious person so it was a very religiously-powered, emotional roller coaster. I clung to my faith, used music as therapy, and practiced mindset mindfulness, things I didn’t even know I was doing then that are so fundamental now.

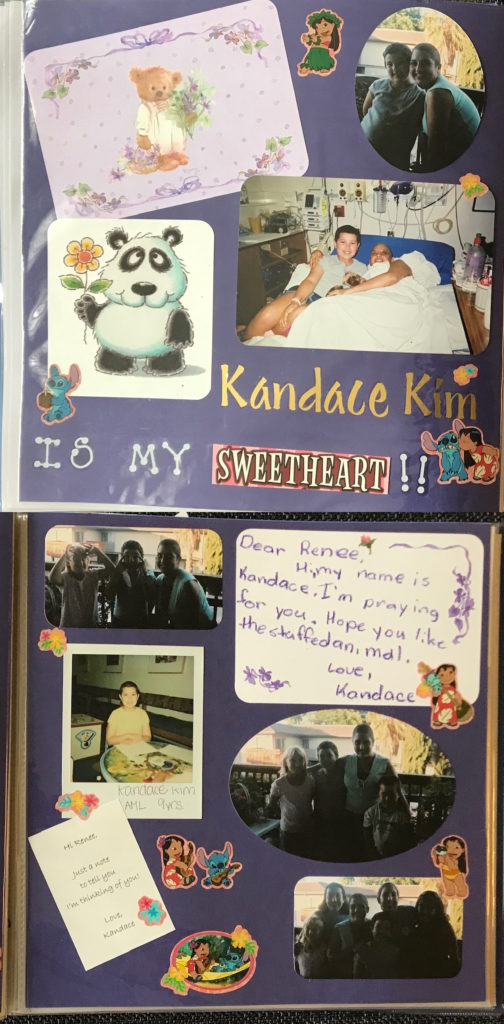

The hardest part was that because I was 18, I was the oldest kid in pediatric oncology. When other kids came by my room, they saw my cheerleading graduation pictures [and] the artwork that my friends left, and they came to me for advice.

I remember hearing one of them say as she was leaving my room, “Daddy, I didn’t know cheerleaders could get leukemia. I thought just kids got it.” Hearing that and not knowing where the hell I’m going to end up was just gut-wrenching. I have no other option. I’m not done yet.

My oncologist, who’s still friends with me today, [would] come over every morning. “Are you still fighting with me? I’m fighting for you. Are you still fighting with me?” And I would tell him, “Yeah, absolutely.”

Every time there was news that this treatment didn’t work or that we had to try this other chemo because it was stronger, my answer was always, “Whatever you have to do.”

When I think back to when I was going through this, I wish I heard more stories to hold on to because all I was holding on to was trying to keep it together because these little, itty bitty pediatric kids are looking up to me.

My oncologist [would] come over every morning. “Are you still fighting with me? I’m fighting for you.

When did you get your diagnosis?

It was the same day that I went to the hospital for that blood test. This sweet old man came over and was talking to me and my mom. He says, “She has acute myelogenous leukemia.”

My mom said, “No, she doesn’t. You have the wrong test results. Her sister just got over mono. She has mono.” He said, “No, it’s not mono. It’s really serious. And if we don’t treat it right now, she’s not going to make it.” I asked him, “I’m not going to make it to what?” And he goes, “To the end of the week.”

I can honestly say it took years for this to set in, that this is what’s going on. The only way I could process it to make sense was that it was like a really, really bad sinus infection and that’s it.

Anybody that I had ever known who had cancer died. Kids don’t die from this. You’re not supposed to. I’m supposed to go do things. I was really involved in youth group and cheerleading. I had plans after high school to volunteer. I was going to work at the camp and go build more houses in Mexico.

I remember asking my doctor, “Okay, so in a couple of months, when this is done, I can go to Mexico, right?” And he goes, “Sure.” I think he knew right then and there how to counter the fact that I had problems comprehending what was going on.

‘If we don’t treat it right now, she’s not going to make it.’ I asked him, ‘I’m not going to make it to what?’ He goes, ‘To the end of the week.’

Treatment

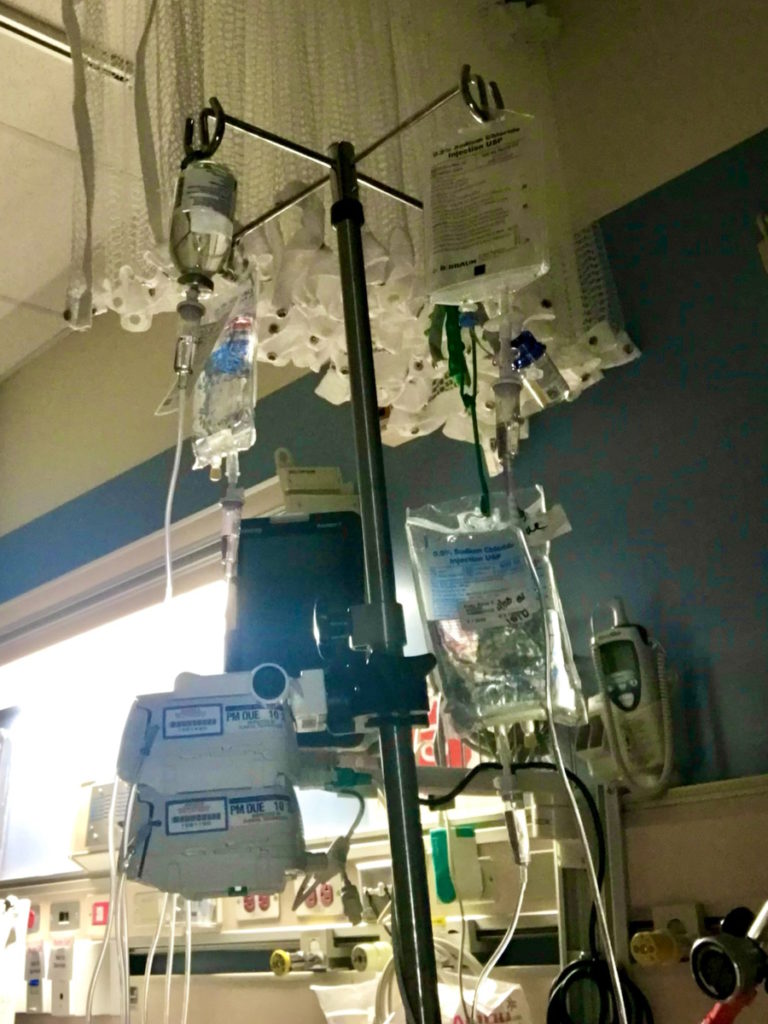

I remember that first blood transfusion, that first bone marrow biopsy, and [the] spinal tap. I remember being in bed, machines going berserk, and telling my mom I couldn’t breathe. Then waking up months later, seeing my reflection in the hospital window of this bald person.

[I] had a patch over my eye because I had an infection. I had an infection from my port. I had an infection from my PICC line. Tubes everywhere. I was completely bedridden.

It was really late at night. I woke up and kept leaning over. My mom says, “What are you doing?” I said, “Who is that person staring at me?” And she goes, “Where?” And I said, “Right there. There’s this weird person staring at me.” And she goes, “Honey, that’s you.” She hit my morphine pump and I fell asleep.

I woke up and my friends and my sisters had made [a] list of all the famous bald people in the world and they put my name at the top of the list. Then they all started dyeing their hair purple.

It just swept over me. I was engulfed in this environment.

Because it was 2002, it was very hush-hush, especially after the recovery. There was nobody to talk to.

The therapist would come by and would be like, “You look really upset today. Is there something bothering you?” And I’m like, “Hmm. Hmm. It’s raining.” I would be so sarcastic. I went to sarcasm to cope because it was so extreme.

What was your treatment plan?

They started me on chemotherapy immediately. I had a PICC line put into my chest and was started on a seven-day treatment.

By day six, the chemotherapy had burnt a hole through the PICC line and caused this massive staph infection. My whole boob swelled and it was just awful. They had to rush me into surgery, remove the PICC line, put it in my arm, and continued with the chemotherapy.

After the chemo was finished, we found out that the chemo did nothing but piss off the cancer. The infection spread. Now I had an infection [in] my eye and things were just going downhill.

They put a PICC line in my neck. By that time, I was in intensive care. They started me on stronger chemotherapy. I believe it was doxorubicin because that’s what basically wiped it out.

I was completely comatose and had about four or five IV poles.

They had to move it. They put it [in the chest area] and it stayed stable for a year. But I had all these other infections now that picked up staph and it was just a mess. By [that] time, they had finally figured out the right chemotherapy to combat the leukemia.

Acute myeloid leukemia is a really fast-growing, aggressive cancer. They blasted me with doxorubicin, sent me over to Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital in Palo Alto, and blasted me with even more chemotherapy. I think the last round was a week’s worth of chemotherapy in 24 hours. It was insane.

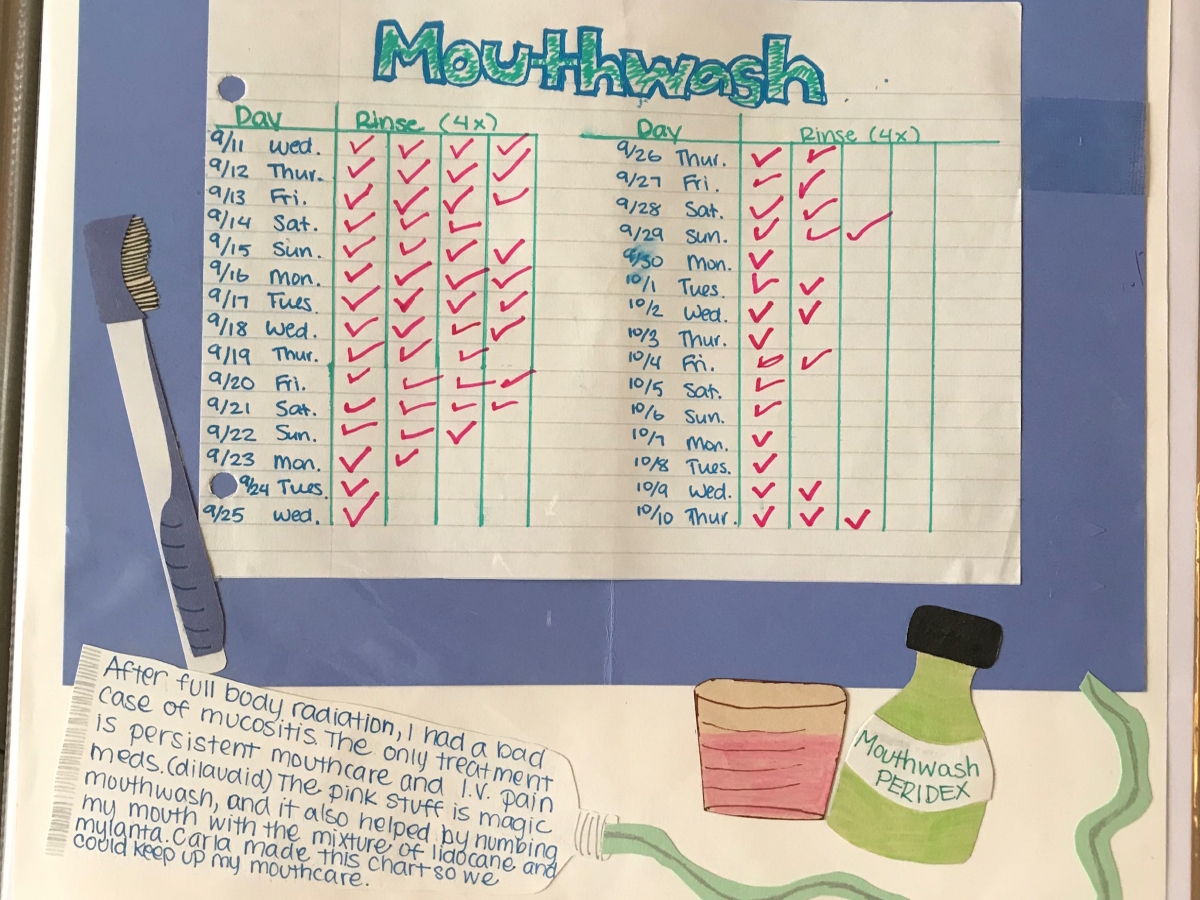

I had mucositis. I threw up my esophageal lining. It was a mess.

‘You can’t start my radiation until you crank up Smack My Bitch Up by Prodigy. I need this to get through this,’ and they did. They totally obliged. You got to do what you got to do.

Radiation

They had me do total body radiation. They had to tape me in this photo booth-looking thing because I had to stand up but I was really weak.

They would zap me then I’d come back later and they would do the back. I had to do it three times a day — front, back, front — and then the next day would be back, front, back. It was like that for a week. I had to do a separate lower-dose radiation treatment just on the lungs.

Bone marrow transplant

After, it was basically wiping out my immune system. I was completely immunocompromised. I was in double-door isolation for months. I couldn’t have visitors. I couldn’t see my friends.

All of my friends are off in college, living their dream, and I’m in prison, in the hospital. I graduated high school in [the] intensive care unit on speakerphone. My sisters accepted my diploma for me.

Most of the time in the hospital, I was clinging to life, bedridden, and in critical care. I was diagnosed in May. By September of that year, I had finally been prepared with chemotherapy and total body radiation to have a bone marrow transplant from my sister.

I have three sisters and lucky for me, two of them matched me perfectly, which is incredible because I’m mixed race. I’m Mexican and Italian so if they didn’t match, it would have been a nightmare.

My bone marrow transplant was the easiest thing out of everything. My doctor carried it in the bag and gave it to me. It was still warm and it was this mushy, orange-ish-looking, goopy, slimy thing in a bag. They hooked it up to my IV.

My sister was in recovery for a couple of hours. I ate cheese puffs and watched Monsters, Inc. for the millionth time. [I had] a lot of Benadryl and morphine.

The day after the infusion, they did [a] bone marrow biopsy to see how much of my sister’s had come in. From day one, it was good to go and immediately multiplied. From that point on, it was just monitoring to make sure that I developed a little bit of graft versus host but not enough to cross the threshold of safety.

I learned how to flush my own lines, mostly because I begged them to not make me come in every single day, twice a day, to flush my lines.

I was allowed to leave but because I was still so fragile, I had to be within one mile of the hospital for any situation. I stayed at the Ronald McDonald House in Palo Alto.

I had IV pumps that I had to continue doing. I learned how to flush my own lines, mostly because I begged them to not make me come in every single day, twice a day, to flush my lines. I told them, “I’m 18. Can you just teach me? I’m off [the] hospital campus. You can teach me.” They taught me how to do it.

I stayed at the Ronald McDonald House for about three months, came home for my 19th birthday, and started to rebuild my life from there.

I was immunocompromised and neutropenic for about a year so I was in complete isolation.

I have a sensitive immune system. It was 2002 so not a lot of people really understood that. I lost a lot of jobs because my health was so fragile and it made me look like I wasn’t a consistent employee.

Remission

When they tested my bone marrow [on] day two or three, it had shown 85% [of] my sister and no percentage of me so as far as acute myeloid leukemia is concerned, I was in remission.

The chances of developing AML a second time were there but not any more of a concern than developing [a] secondary cancer.

They told me from the very beginning that the treatment that I [had] to have does cause other cancers and that because of my ethnicity, I’m already on the cusp of some other health issues, like heart disease and diabetes.

The protocol was to continue monitoring me as if I still actively had cancer. They outlined a five-year regimen. I had to get all of my vaccinations again [within] a certain time frame.

I had a lot of radiation done to my body. I had serious wounds and scar tissue. Radiation, scar tissue, and cancer just love to group up so there was concern of tumors, but [they didn’t] want to do mammograms [at] 22 so it was just ultrasounds and regular checks.

We’ve been monitoring my blood work every 3 to 6 months for the last 20 years. I have chronic anemia and my immune system is not my age. I’m 38. My immune system is only 20 years old so that meant going back to work was really difficult because anywhere I worked, I instantly got sick.

I [was] already [burdened by] chronic issues from leukemia, but now I have a sensitive immune system. It was 2002 so not a lot of people really understood that. I lost a lot of jobs because my health was so fragile and it made me look like I wasn’t a consistent employee.

The ripple effects are still felt emotionally, physically, and financially. Honestly, I didn’t start to cope and deal with my leukemia until I got breast cancer. I packed it away. I didn’t know where to go to cope with it.

If anybody asked me about the scars, I would make up stories… I didn’t want to be deemed the ‘cancer girl.’ Nobody falls in love with [a] girl with cancer is how I always saw it in my head.

Fertility

The effect of cancer treatment on fertility

In the back of my mind was this huge, unspoken conversation about fertility. I want to be a mom. I obsessively asked, “Do you know what my chances are after I recover from this stuff? If I’ll be able to get pregnant?”

I asked everybody to the point where they were like, “Renée, you need to just let this go.” It was like that for 11 years. I researched what tests we could do. I did everything possible. For 11 years, the answers were always, “There’s nothing. It’s not happening.”

From the time I was diagnosed, they told me that the treatment will cause infertility. I remember asking them right away, “How do we save my fertility?” They told me flat out, “We don’t have enough time to do what we need to do to save your fertility options.” And in 2002, they really didn’t have the science backing it too much either.

They had to prepare me for the worst because they really didn’t know either and I respect that. It was hard to process. Being told at 18 that you’re not going to be able to have kids then finally being able to recover and be free, you go a little crazy. You’re like, “Screw the world! I’m going to love everybody then and mask my pain with that.”

I went from being this pure, Catholic-raised, Christian girl where I’m told to respect my body, that my body is a temple, and nobody is to touch it or violate it to wide open, everybody touching me, everybody feeling things, everybody looking, taking pictures, cutting me open, putting in this, putting in that, and it was like, “What happened to this temple that I was?” It was really hard to rebound from that and to have all these scars associated with it, too.

[I was] obsessively asking and trying to find out, “If I eat more berries, will that increase my fertility? If I do this pose, will that help?” Trying whatever I could.

Then I got into a relationship where we were both really equal in if we have kids, that’s great [and] if we don’t, it’s no big deal. We were together for a long time.

After going through [treatment], my body went into medical menopause. I was taking hormones so I could get my period. It had been 10 years since my transplant. The doctors wanted to do a full panel test on me so they could scan everything and see what was going on. They wanted me off all of my hormone control medications.

I go to my doctor… She’s doing the ultrasound… She had me sit up to see and she goes, “Renée, you’re pregnant.”

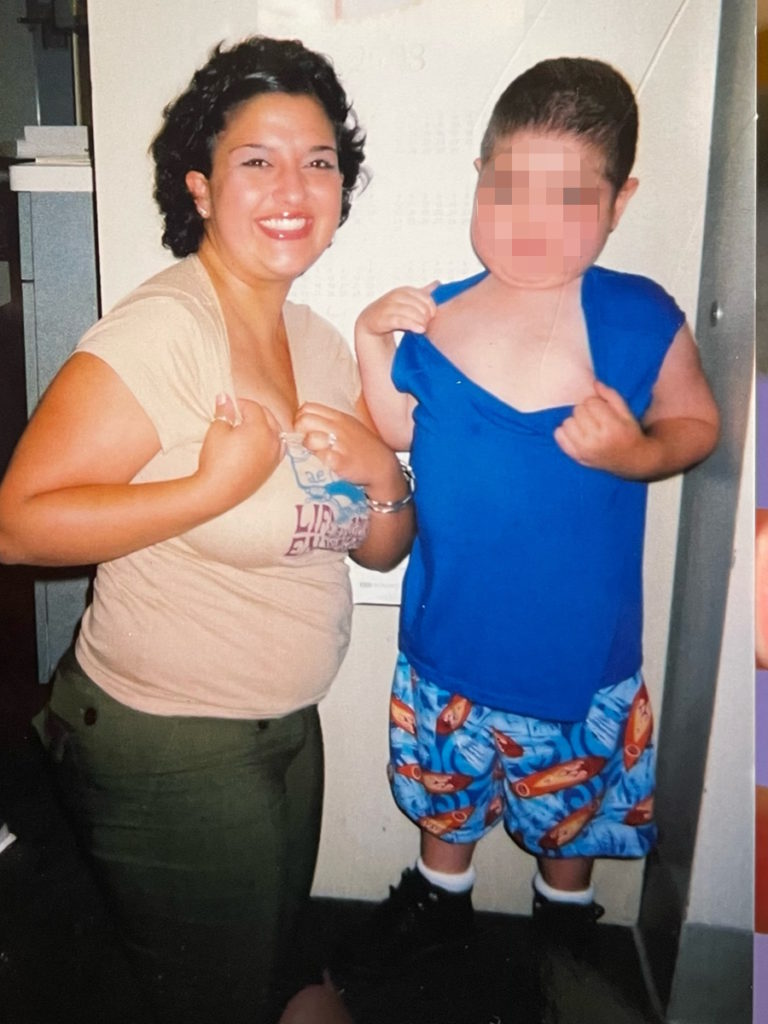

Getting pregnant against all odds

I was off my medications for one year and got pregnant. Didn’t know. Started feeling some symptoms.

I go to my doctor, [who] has been my doctor for 15 years. She knows me very well. She’s doing the ultrasound and she’s already having the conversation with me. “Okay, Renée, if it’s a tumor, it’s going to probably look kind of clustered and it’s going to look like… Oh.” And I said, “Kind of like O? Like it’s going to be like an O shape?” And she goes, “No, look!”

She turns the monitor and grabbed my leg and said, “Did you see that?” I said, “Yeah, what is it?” And she goes, “It’s a baby!” And I said, “Whose?” And she goes, “Yours!” And I said, “How?” She’s like, “Well, you know how, but you’re pregnant!” And I was like, “No, I’m not. I can’t be.”

She had me sit up to see and she goes, “Renée, you’re pregnant.” I’m like, “No… You’re sure?” She’s looking at it and goes, “Oh my goodness.” I said, “What?” She goes, “You’re 14 weeks! You’re having a baby in six months!” “What?! What?!”

It was the most confusing day of my life. I had to call all of my doctors. I called Lucile Packard. All of them were like, “Wait. What?” As soon as it settled in, they all said, “We can’t wait to see our baby.” Everybody said Ava was theirs.

That became this quest of, “What am I getting myself into? What is my health? How does my health impact this baby? Is she going to have any side effects because of what I’ve been through?” It was really interesting to be able to go down that door and get in that space of all these different conversations.

It had been so much time since my treatments that if anything, she’ll be really small, probably premature, and [have a] low birth weight. But other than that, everything else looked perfectly fine.

The beautiful part was that during my pregnancy, all of my chronic symptoms — fibromyalgia, migraines, light sensitivity, and eye issues — disappeared. I had a beautiful pregnancy. It was easy. I ate ice cream every day. It was lovely.

We found out that she was stuck in my pelvis upside down so I had to have a C-section to get her out. I went into labor two and a half weeks early. I had a planned C-section that was now moved forward. But that went perfectly fine. She was small but healthy and has been growing like a vine ever since.

It was a full-circle moment. I knew that if I wanted to be a mom, I could go and adopt but I wanted to feel [being pregnant]. I remember bargaining with God. “I’ll do anything. Anything. You just let me feel it one time,” and I got lucky.

She was small but healthy and has been growing like a vine ever since. It was a full-circle moment.

Words of advice

Hold on with an iron grip. I believe in manifestation. I believe that our universe is listening to us. If you think it, believe it, pray it, hold on to it, eat and breathe it, and obsess about it in a positive way, you’d be surprised at [the] results. It might not be exactly the way that you planned it, but it’ll be close.

We all came from stardust so to be where we are right now took a lot of work by forces that know you better than you know [yourself].

Does it hurt? Does it suck? Yeah. But sometimes, when things don’t work out the way that you plan them, it’s because it wasn’t your plan. Understanding that is powerful. Knowing there will be a time [when] you will look back and remember when you prayed for the things that you have.

Hold on. Keep asking questions.

When things don’t work out the way that you plan them, it’s because it wasn’t your plan and understanding that is powerful.

Hearing other patients’ stories

After I got through leukemia, my oncologist came over and told me that he had another patient that was about my age that had just been diagnosed. She was really upset and [asked if] I could go talk to her and share my story. And I did.

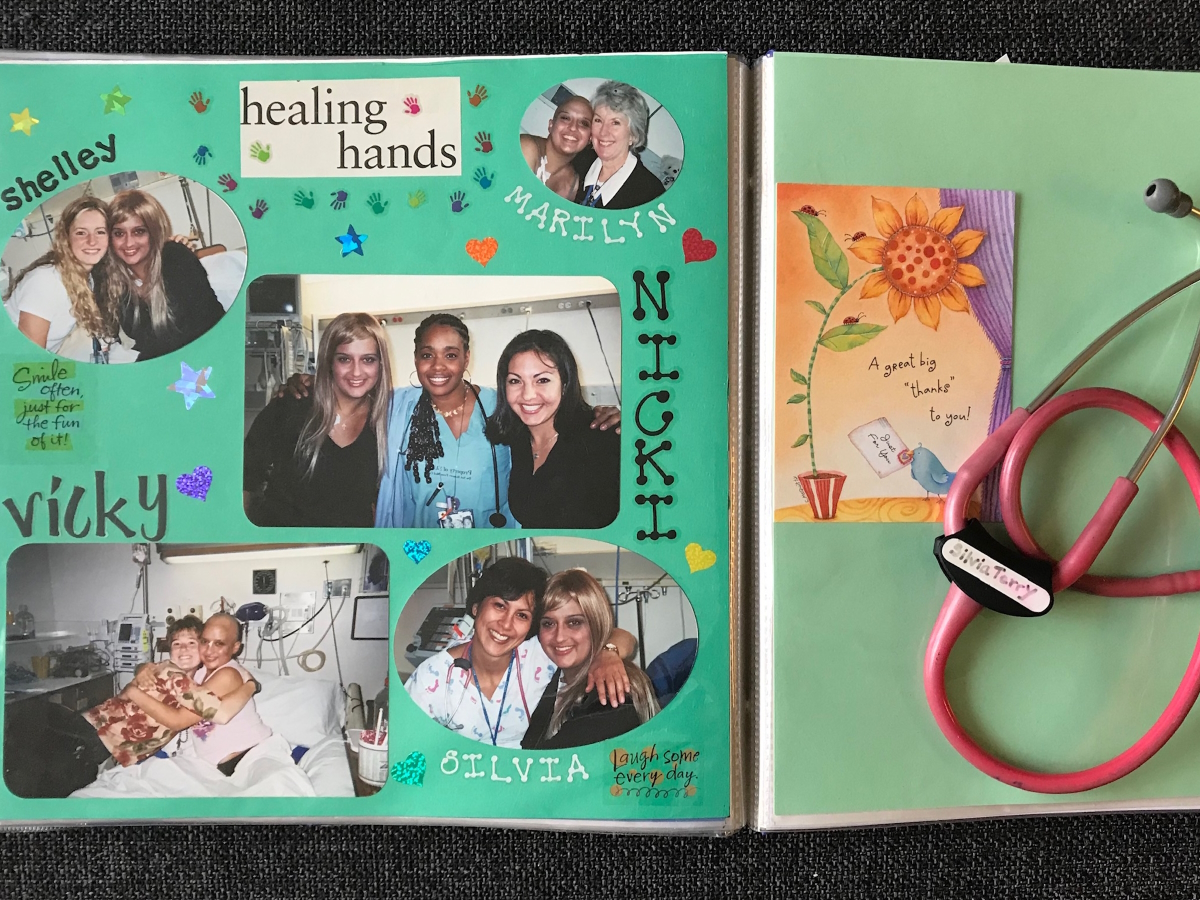

It went from one patient to another [and] another to [it] becoming a routine. When my oncologist met new patients that were struggling with accepting what’s going on, he called me to come over. I’d come to the hospital, sit there, collect their hair with them and put it in the basin, share my story, and show my scars.

I wish I had people that were older that came to my bedside and told me their stories. For me, it was an eight-year-old little girl and she’s still my soul sister to this day.

We need to eliminate the shame of sharing our personal health issues and that we shouldn’t talk about this. It is private, but it’s also very emotionally deep. If we don’t talk about this kind of stuff, it will [have a] ripple effect and impact the rest of our lives.

When we talk about it, it kind of clears those clouds so that that little sliver of light gets in. It’s all you need. Just a little sliver of light.

We go through difficult things in life but to hear that somebody else went through it is comforting… When we talk about it, it kind of clears those clouds so that that little sliver of light gets in. It’s all you need. Just a little sliver of light.

Renée went into remission after going through chemotherapy, full-body radiation, and a bone marrow transplant. For the next 20 years, she’s monitored closely. After a regular breast self-exam, she noticed that one of her breasts was shaped differently. A mammogram and a biopsy reveals she has stage 2 breast cancer.

Read Renée’s Stage 2 Breast Cancer story here »

Inspired by Renée's story?

Share your story, too!

More Acute Myeloid Leukemia Stories

Russ D., Acute Myelomonocytic Leukemia (AMML), with NPM1 Mutation

Symptoms:Flu‑like symptoms, profound fatigue, blood pressure drop, shortness of breath

Treatments:Chemotherapy, clinical trial (menin inhibitor)

Shelley G., Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) with NPM1 Mutation

Symptoms: Fatigue, rapid heartbeat, shortness of breath, low blood counts

Treatments: Chemotherapy, clinical trial, stem cell transplant

Joseph A., Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML)

Symptoms: Suspicious leg fatigue while cycling, chest pains due to blood clot in lung

Treatments: Chemotherapy, clinical trial (targeted therapy, menin inhibitor), stem cell transplant

Mackenzie P., Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML)

Symptoms: Shortness of breath, passing out, getting sick easily, bleeding and bruising quickly

Treatments: Chemotherapy (induction and maintenance chemotherapy), stem cell transplant, clinical trials