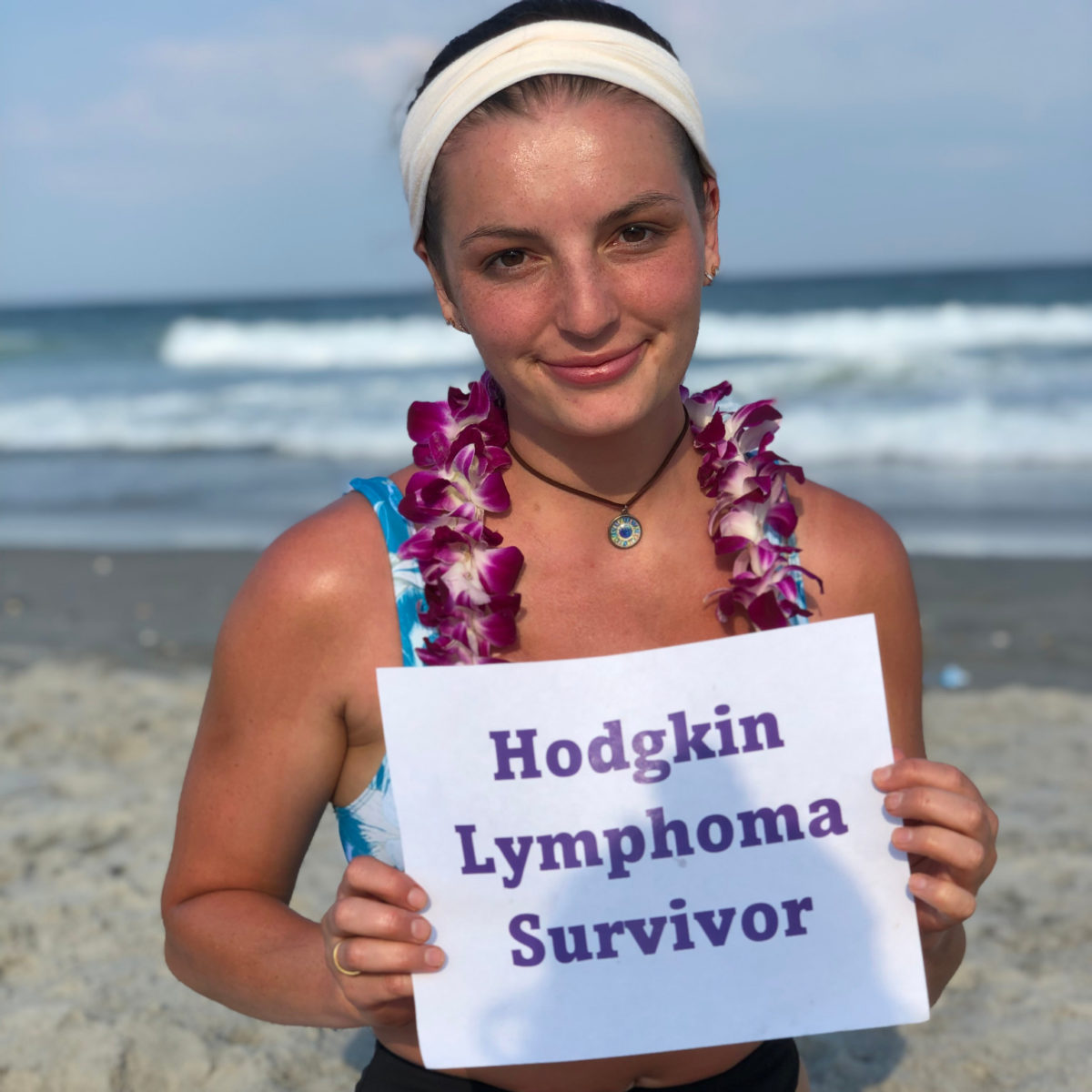

Sam’s Relapsed Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Story

Sam was diagnosed with Hodgkin’s Lymphoma at 38, which relapsed within a month after ending treatment.

She shares the complications of being a doctor-patient, the importance of being honest with your medical team and having clear lines of communication, and the delicate balance of advocating for yourself.

This interview has been edited for clarity. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider for treatment decisions.

- Name: Samantha S.

- Diagnosis:

- Hodgkin’s Lymphoma

- Symptoms:

- Fatigue

- Cough

- Fast-growing lump above the collarbone

- Treatment:

- ABVD chemotherapy (Dropped Bleomycin after 2 cycles)

- Relapse Symptoms:

- Feeling unwell

- Pulmonary symptoms

- Lump reappeared

- Treatment:

- Brentuximab

- Cyclophosphamide

- BEAM chemotherapy

- Autologous bone marrow transplant

I love my doctors and my healthcare team, and I also need to be able to ask questions about my life

It was so tough in the beginning because it was one year into the pandemic. I was really tired… It was such a hard time [with] so many hats to wear so I just discounted my fatigue

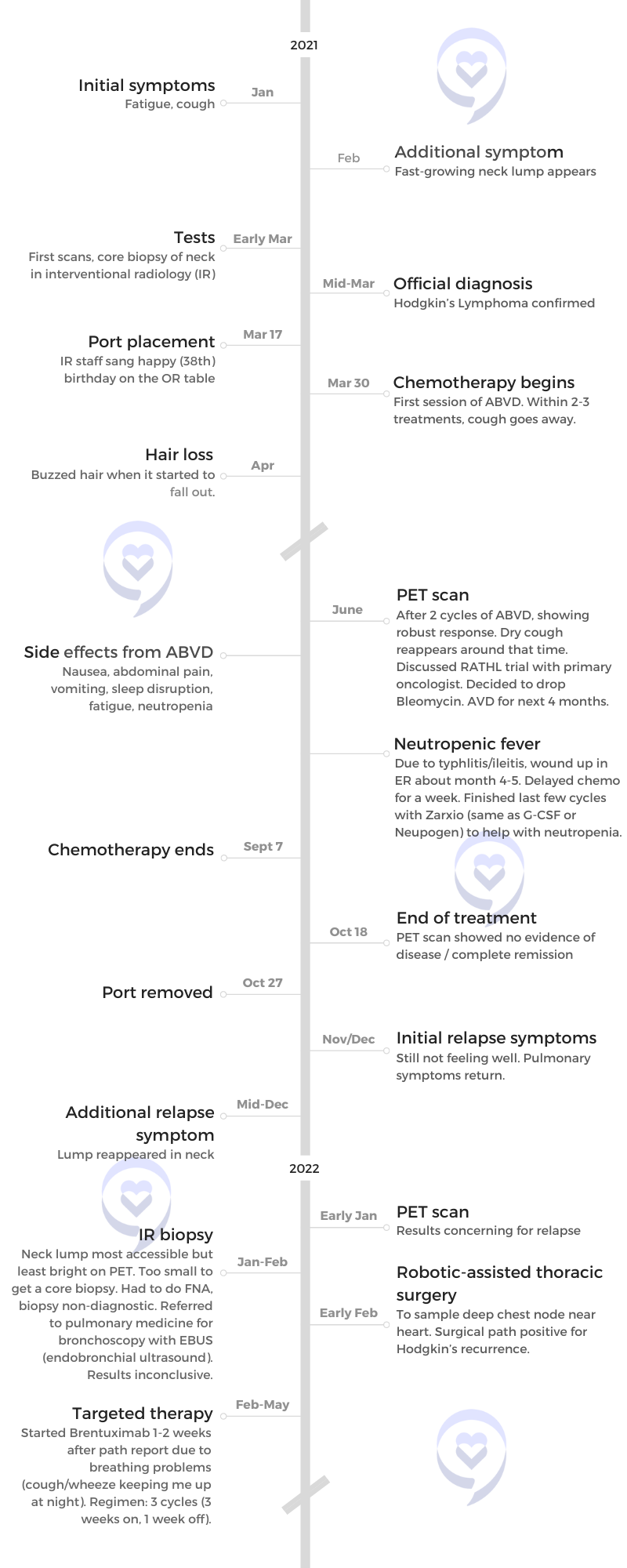

Pre-diagnosis

Introduction

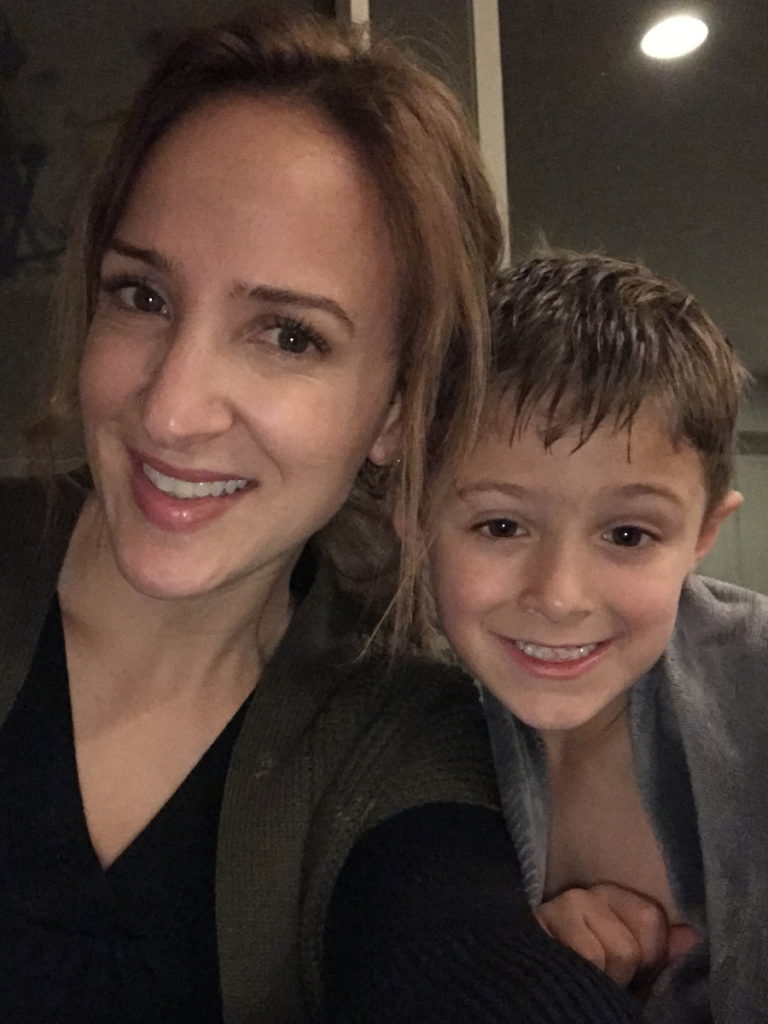

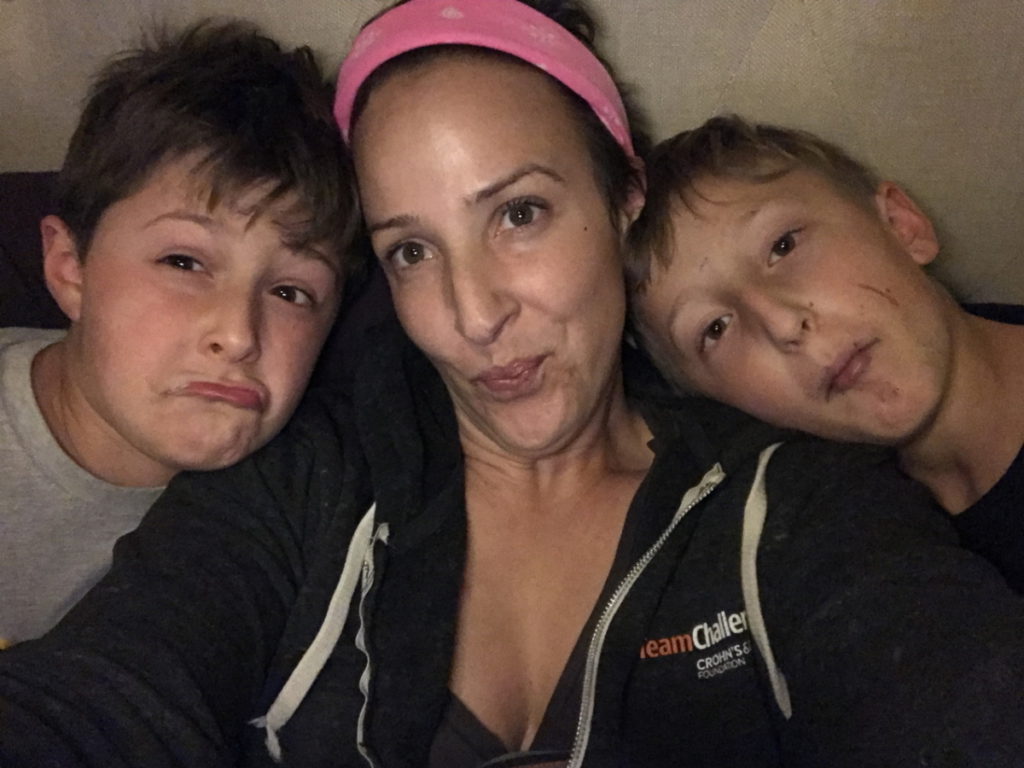

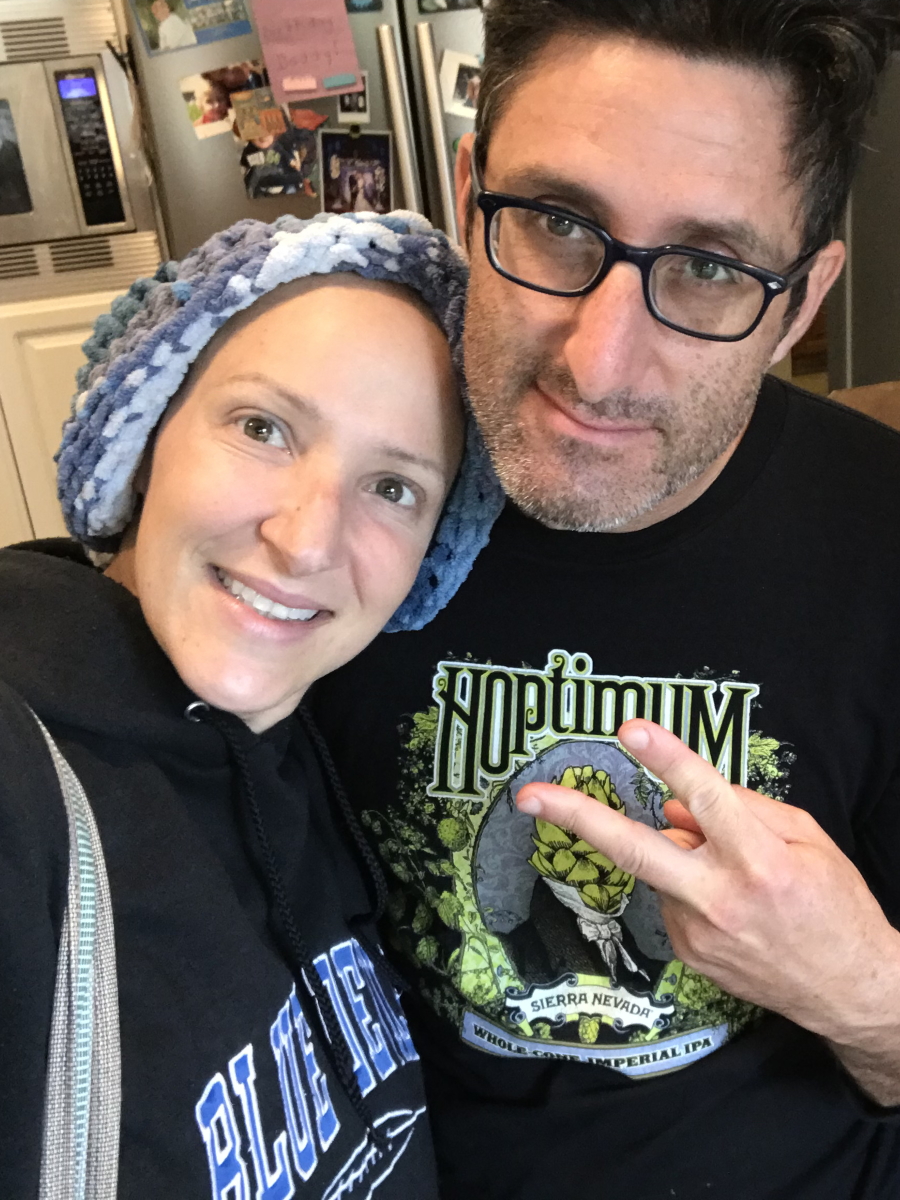

I am a mom of three adorable kids ages four, nine, and ten — almost 11. My husband is amazing. We’ve been together since before medical school. We’ve been buddies since the beginning.

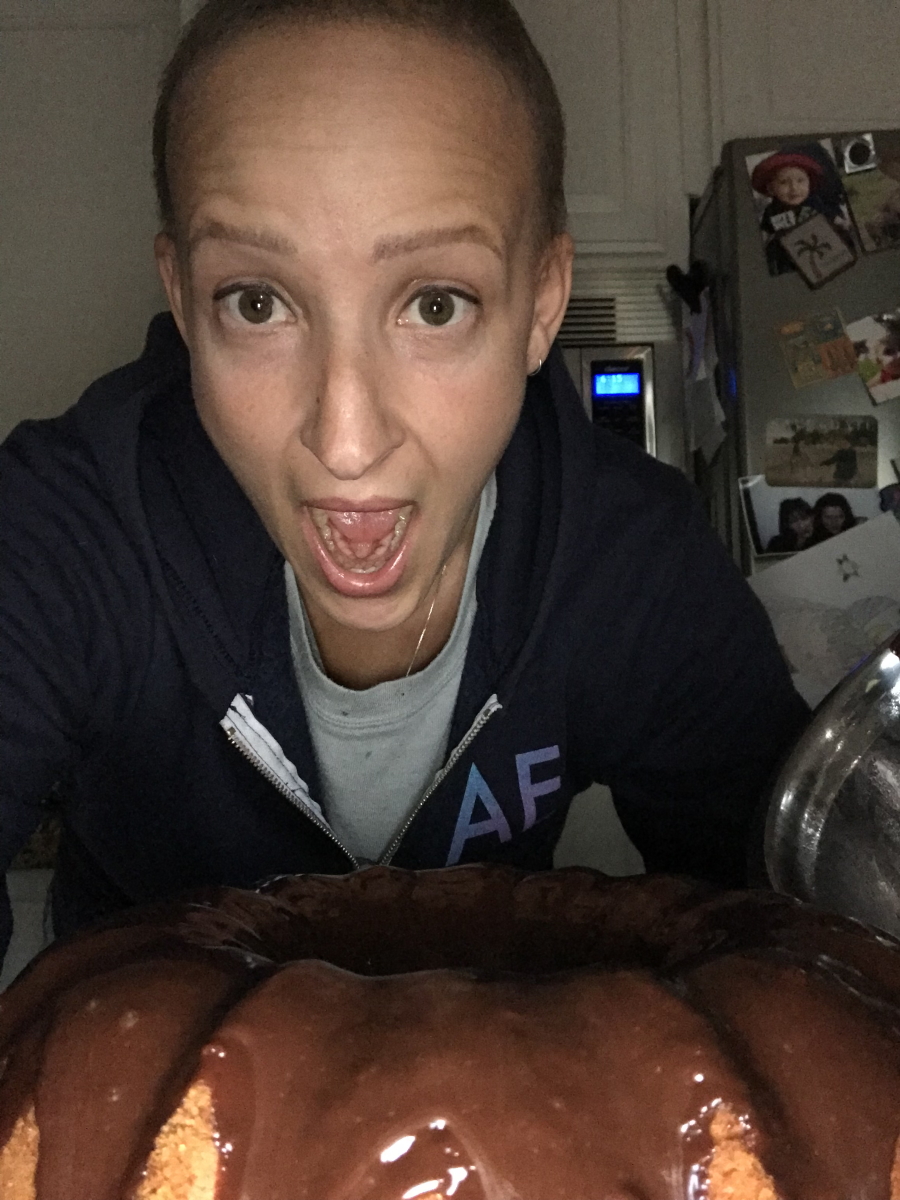

I’ve been a long-distance runner for many years. I love jogging, running, baking, hiking, playing guitar, and painting. Some of those things I did later on when I had my transplant at Stanford Hospital.

I love being a doctor in my community, too, when I’m feeling better.

Initial symptoms

It was so tough in the beginning because it was one year into the pandemic. I was really tired, having trouble getting past 8 o’clock at night with bedtime and bath time, and then getting back to patient notes after the kids were sleeping. I thought, Every doctor is tired right now, especially doctor parents and even just parents that are homeschooling their kids during the pandemic. It was such a hard time [with] so many hats to wear so I just discounted my fatigue. That went on for maybe a month or so, maybe two months.

I also had a cough, predominantly at nighttime. There had been some wildfires in the area where I live. I had a ton of excuses for why I was coughing. I’d be coughing so hard that I slather myself in Vicks VapoRub and take steamy baths in the middle of the night to try and calm my breathing down, thinking, I must have some kind of asthma or reactive airway. All these justifications [for] why I wasn’t feeling well and have these symptoms.

I started getting a rock-hard, rapidly growing lump right above my collarbone. Then I knew. I even said to my husband when I started to feel it, “I think I have lymphoma.” I specifically said lymphoma. It was just so classic to me in my mind.

Shortly after, I put it all together — cough, fatigue, and this lump. This doesn’t feel like a benign lymph node. This feels like I have a rock that’s coming up above my collarbone into my neck area.

Within a week, there was a difference in [its] size. It just had all the features of a lump that’s concerning. A lot of people don’t have rock-hard lumps — they have more rubbery lumps — but I just knew I had to get it checked out.

Shortly after, I put it all together — cough, fatigue, and this lump. This doesn’t feel like a benign lymph node

The process of getting diagnosed

It was really scary. First, finding the time to get an appointment, doing the dance of, “Am I imagining these things? Is this really something worth taking time off work for?” I want to save my sick time for my family and things going on. Logistically, it was tough.

Being a doctor, I knew that I had a left supraclavicular node and I knew exactly which node it was — Virchow’s node. I was hoping that it wasn’t that.

One of my PCPs at the time ordered a thyroid ultrasound saying, “It could be a thyroid nodule; it’s probably [a] thyroid nodule.” In my mind, even though I thought this isn’t, I think they were hoping that it was a thyroid nodule and I was hoping it was, too.

I was able to get a thyroid ultrasound. When I was in the ultrasound suite, the ultrasound tech said, “Your thyroid’s normal,” and I could sense a “but” there. I said, “So what’s going on? Can you just give it to me straight?” She said, “I’m a tech. I really can’t diagnose you with anything but see these?” She turned the ultrasound probe. I looked at the screen and went, “Ugh.” It looked bad, like some kind of tumor or mass. Then I said, “That looks like tumors or masses.” And she said, “Yeah, it does, but I’m not a doctor.” She was very professional, given the situation. It’s so tough.

It looks like tumors…

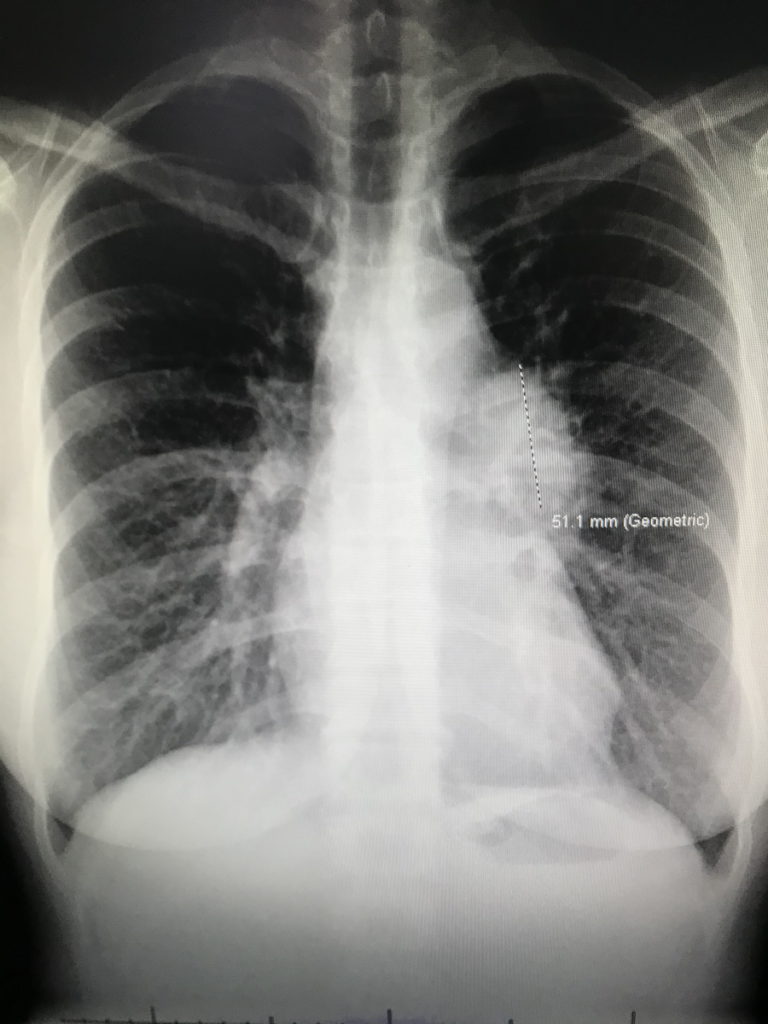

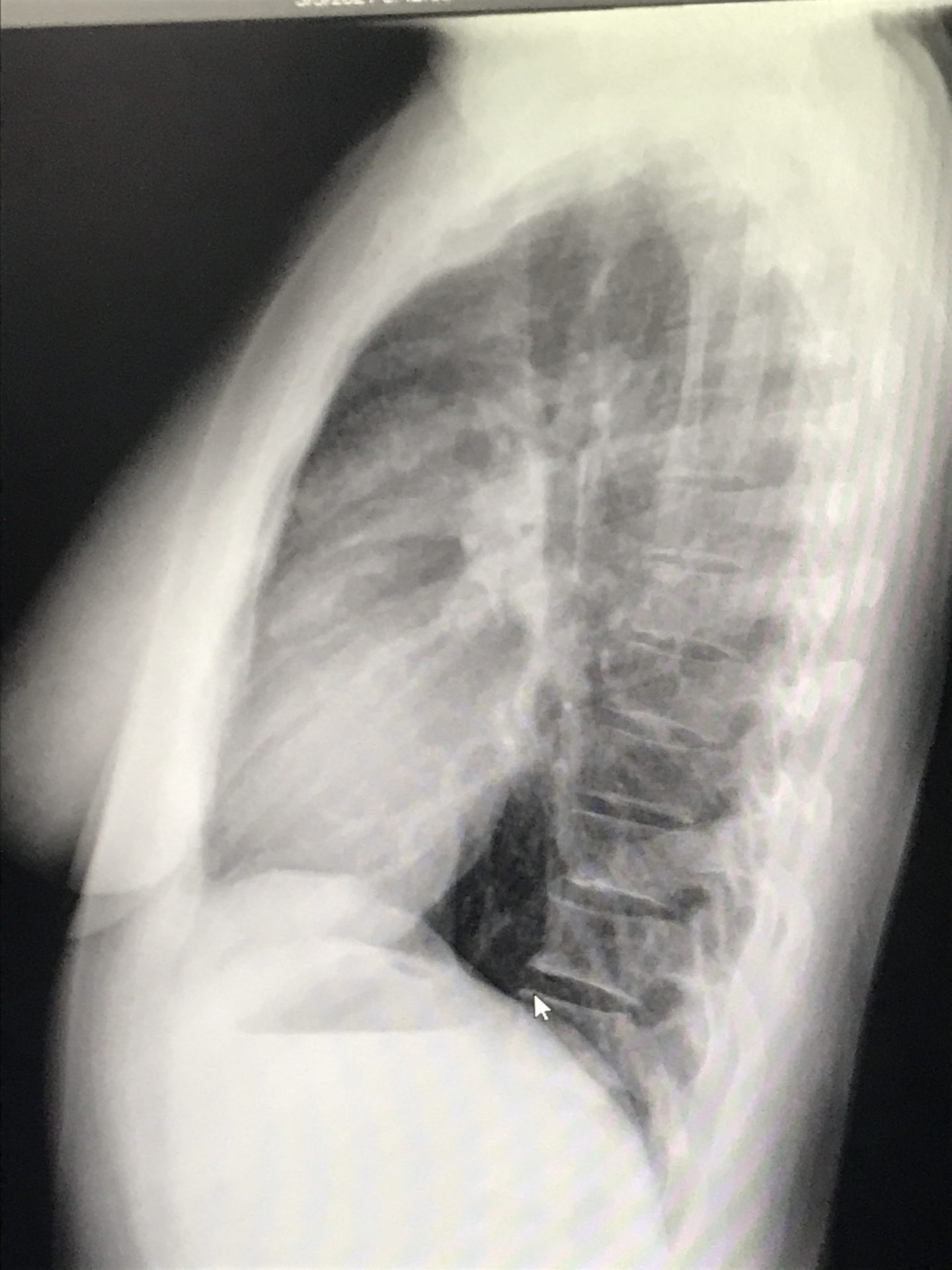

I called one of my friends at work — another doctor — crying on the way home, saying that it looks like tumors. She ordered a chest X-ray for me and I got the chest X-ray before my clinic day. I then went straight to my office, opened my own chest X-ray, and saw that not only were there masses near my collarbone but there were masses in my mediastinum — the middle of [the] chest cavity. It didn’t look right. It was like it was somebody else’s chest X-ray.

I was totally numb. I couldn’t even process that that was mine. I walked into my friend’s office next door — an amazing nurse practitioner — and said, “I think I have cancer. I just opened my chest X-ray and [there are] masses and I have lumps in my neck. I’m pretty sure I have cancer.” I said it with this blank look on my face. Then I said, “Okay, I’ll go see some patients now,” and just went on about my day.

I was completely in shock and happy to focus on everybody else and not myself because that was just terrifying. I saw patients all day and then over the weekend, things evolved. I decided I better take some time to figure out what’s going on with me. I probably shouldn’t be seeing patients while I’m going through this. And I’m glad I took that time during the diagnostic process.

I was totally numb. I walked into my friend’s office and said, ‘I think I have cancer…’ I was completely in shock.

Diagnosis

Getting the official diagnosis

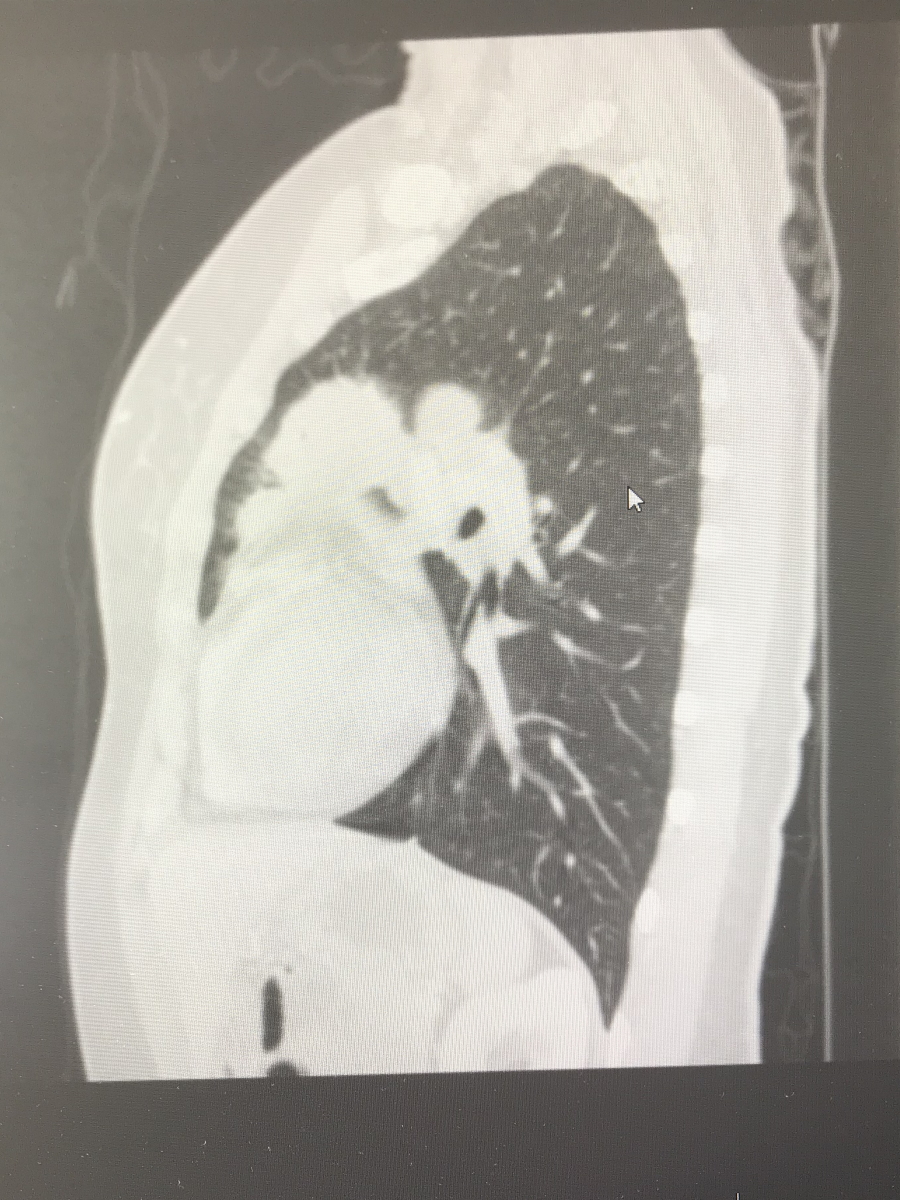

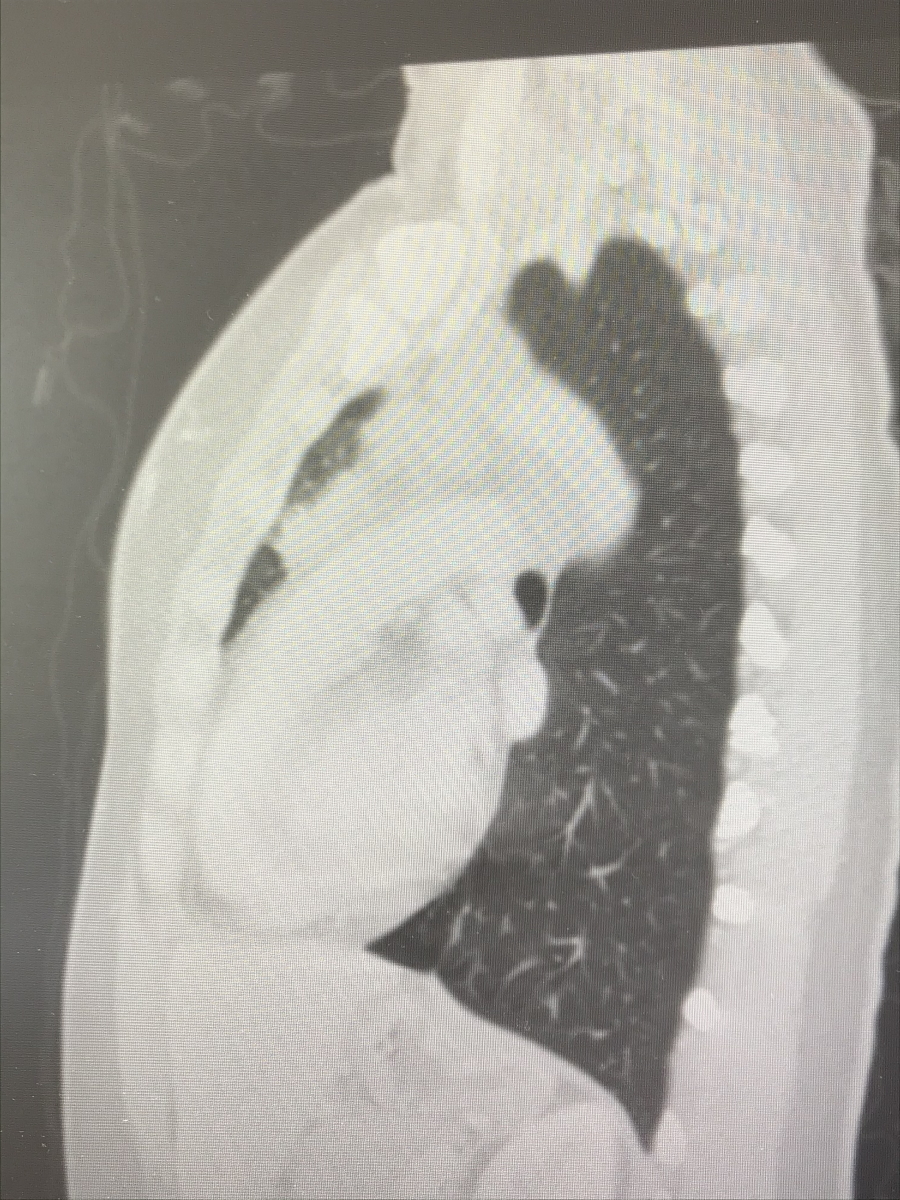

This is where my angst as a patient started, I think. After having that ultrasound and chest X-ray, I had some CT scans done that confirmed everything going on in my chest.

Next, you need tissue. [There are] generally two ways to get a biopsy in the head-neck area — interventional radiology [and] head and neck surgery. I was initially referred to head and neck surgery for a video visit to look at the scan and see if the surgeon [was] going to be able to biopsy or not. Was it reachable based on location?

I got on the video visit with my husband and the doctor said, “Hey, Sam, I saw your CT. I don’t think I’m going to be able to safely biopsy that because it’s too close to your carotid artery so I’m going to refer you to interventional radiology.” I thought, Okay, that makes sense. I wasn’t hysterical.

I had a three-year-old daughter that I had just finished nursing within the month or two before so I still had milk in both breasts and I guess it lit up on my CT scan. When I looked at my scans the weekend before the appointment, I wasn’t even concerned about what lit up in my breast. Then the next thing they said, without knowing a little bit more of my history, was, “I see something lighting up in your chest so I’m pretty sure you have metastatic breast or lung cancer.”

The doctor told me this and there was no pathology yet. I knew it was probably my breast milk. But that What if? part of my brain said, “A doctor’s telling me that I probably have metastatic breast or lung cancer.” I started hearing this high-pitched [sound] and the light drowning out everything. My husband sounds like he’s underwater and he’s right next to me. I started bawling.

I don’t even remember finishing the video visit. I think my husband finished it for me because I went nuts. My next vision was [of] my daughter at my bedside, giving me hospice care before I die. My mind flashed to a situation that could have potentially happened if I was a young person with those cancers. And that’s not even rational either because these days, people [with] late-stage cancers are doing really well and able to live much longer than before with all the new therapies. But I wasn’t thinking that. “Oh my god. He’s just giving me a death sentence.” That’s how I felt.

I was referred to interventional radiology and that doctor was amazing. My new PCP, my whole team, [and] all my colleagues were helping to expedite things. I was biopsied pretty quickly. They fit me in within a couple of days.

When I found out, my OB-GYN called to see how I was doing. She’s a colleague and a friend. While we were on the phone, she said, “Sam, your path just came back. Can I open your path report?” I said, “Okay, okay, you can do it. You can open it.” She opened it and said, “It’s Hodgkin lymphoma.”

I started bawling and was like, “Thank you, thank you, thank you.” At that point, there was so much whiplash and it was such a drastic swing from [when] it was a very different situation potentially. I was so grateful that this was Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

I just spent that weekend on a high. I was skipping around, “Okay, I’m going to live. It’s just going to be a touch of chemo.”

But it didn’t turn out that way.

Breaking the news to the children

My older two were eight and nine. We have gone through a lot of illness experiences with them. My husband is a liver transplant recipient and had a bout of testicular cancer in medical school and some health issues so we weren’t new to being on the patient side of things. In fact, I spent so many years as the wife in the waiting room eagerly awaiting any information. I know what that feels like and I always tried to remember that when doctoring people. Now it was me. It was such a shock.

When [my husband] was sick, initially, we would try to keep it from them because we thought we’re protecting them. Until there’s something that they can see visually, we don’t need to tell them. But kids are smart and they pick up that nervous energy, that tension.

Giving them some version of the truth that’s digestible developmentally at their age is really important.

When my husband was really sick one time — I thought we were keeping it all together — my four-year-old (who is 10 now and was nine when I first got diagnosed), his hair fell out. I took him to the doctor and she did all these tests. We were concerned about some illness and when we ruled everything out, she said, “I think his hair fell out because he’s really stressed. Is there anything going on?” I told her that my husband had just had a hemorrhage, we were waiting for a liver transplant, and he’d been in the intensive care unit.

She put us in touch with a child life specialist who guided us and said that kids see the visual, they feel the stress, and their minds fill in with the worst possible scenario. Sometimes, giving them some version of the truth that’s digestible developmentally at their age is really important.

We learned that earlier on and we knew that we were going to have to share this with the kids, at least the older ones. Things were about to get real with chemo and I was going to look really different pretty soon.

We decided to separate the older boys for the conversation. My older son said, “Wait, you? You’re sick? What are you talking about? Dad’s the one who we always worry about and you were just running 10 miles last week.” We told him and then we told our younger one.

The responses were really different. My older one was really mature and expressed his shock very openly. The younger one, the middle son, said something like, “Okay. Can I go play basketball?” He heard it, but he wasn’t ready to process anything. We didn’t tell our daughter until I had to buzz my hair and all that. She’s three at the time.

Treatment

There was some question about my staging because I had lung tissue involvement. Am I really 2AE or am I stage 4? The extra involvement of organs outside the lymph nodes can potentially be stage 4. When your lungs are involved, it’s somewhat controversial. If it’s continuous with the lymph nodes in that area, then you’re still 2.

What I understood at the time was that it would impact the length of chemotherapy because if you’re earlier stage, you might get two to six months depending on any number of things. But if you’re a stage 4, you’re almost certainly getting six months of ABVD.

They use the Ann Arbor classification and that’s the most classic one. Is there one group of lymph nodes above the diaphragm or two? Then once you’ve crossed the diaphragm to the other side, where your belly is, that tends to be stages 3 and 4.

[There are] other exceptions to those rules and different ways that you can come up with different stages and risk factors. Do you have anemia? Do you have elevated inflammatory markers? All kinds of other things can be taken into account that help put together a whole treatment plan, your true stage, and your prognosis with that stage if you have these other features on lab work.

ABVD chemotherapy

I think this is where I started becoming or at least feel like I was becoming labeled as the anxious patient because I had questions, [like] the lung involvement and what that meant. It started to feel like, “We’re going to discuss it and tell you what you are and what the recommendations are,” and really in a nice way. More like just let us take care of you and you focus on getting better.

For me, it didn’t feel that way. I want to be part of the conversation. I want to really understand what’s happening to my body [and] what the rationale is. Why not stage 4 or why stage 2? How did you decide that? I think physicians aren’t always used to getting those kinds of questions and I wasn’t asking anybody to defend the decision. I really wanted to understand. When I started asking those questions, I began to feel like, “Oh, geez, I’m a little too much right now.”

I was concerned from the get-go that I was really a stage 4, that it was more complicated, or that somehow four months of chemo wasn’t going to cover me. I just had that fear from the beginning. I don’t know why.

Would it be two months of radiation? Would it be four months? Would it be involved-field radiation? Some of the terms I had started reading about. I had to look them up, too, even though I’m a doctor. Would it be six months? When I started asking those kinds of questions and why this and not the other, that’s when I started to feel that things were taking on a certain vibe.

The answer that I got was, “Just start the chemo and then we’ll see what the two-month PET shows,” because that’s how it tends to go with Hodgkin’s. You get a PET scan after two months and see where you’re at. The response determines the rest of your outcome. Do you need more chemo? Do you need less chemo?

My second month PET scan was really good. The concern was just two more months of chemo, four total. I was concerned from the get-go that I was really a stage 4, that it was more complicated, or that somehow four months of chemo wasn’t going to cover me. I just had that fear from the beginning. I don’t know why.

I pushed for six months because I felt like I really want to slam this thing. I wanted just one and done if there’s any chance of relapse.

I don’t want to ever see this thing again. And for many people, that will be the case with Hodgkin’s.

By that point, even [after] four months, I started to feel really tired — that Mack Truck feeling is what I call it. I’d lay in bed for about three days after every ABVD. My mom called it the lagoon because I would just lay there with the lights off. The fact that I was advocating for more, I really didn’t want to do it but I thought if this [did] anything to positively impact my survival, then I wanted the more aggressive treatment.

I think they’re like, “Okay, she’s nuts. She wants two more months of chemo.” But I don’t want to ever see this thing again. And for many people, that will be the case with Hodgkin’s.

Side effects from ABVD chemotherapy & how to manage them

ABVD is a tough regimen. It was hard to figure out the toughness of things. Was it just the chemo? Was it the meds they were giving me to help with the side effects of chemo? That was hard to sort out at various times.

Nausea

Nausea was a big issue for me so I was on a lot of different anti-nausea medications — Zofran, Ativan, Phenergan. I was getting steroids. I also had Zyprexa one or two times, which is an antipsychotic medication. That was horrible. I was a zombie for days and couldn’t think at all — worse than the typical chemo brain. I really can’t put any sentences together. For some people, it’s an amazing drug and it works really, really well.

That’s one of those things. You’re trying different medications — some things are going to work for some people and other things are going to work for other people. It’s just important to know what’s out there so that you can ask for it.

Hair loss

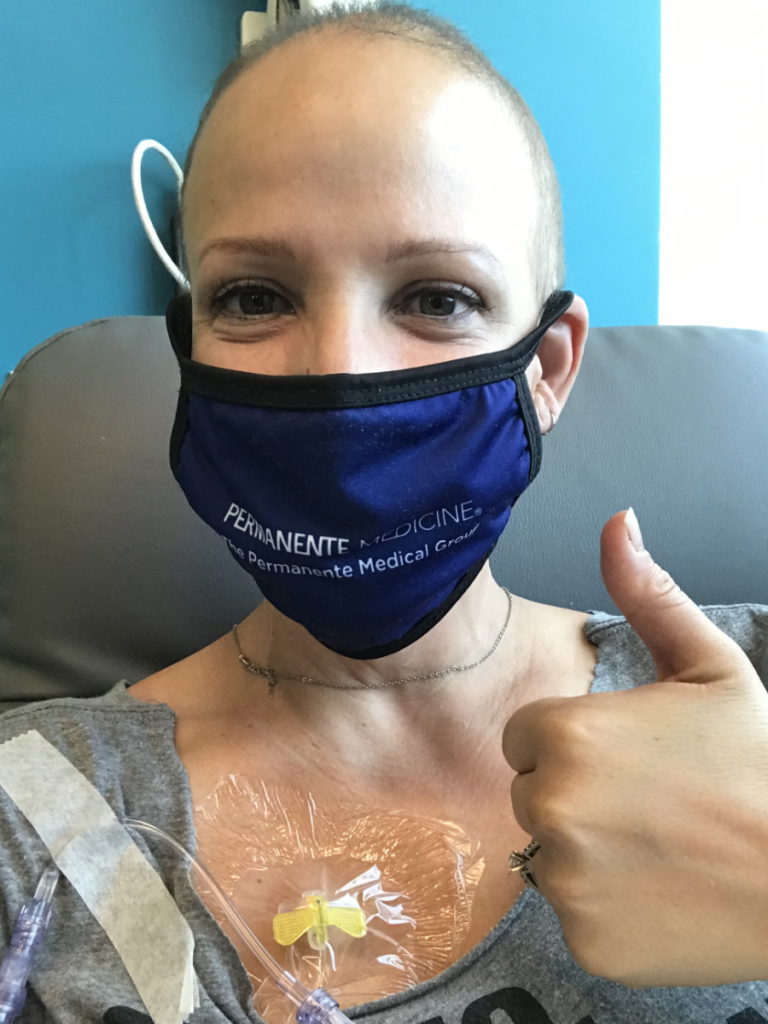

That was a big turning point for my daughter. She’s three at the time and that was a big visual cue to her that something was really wrong, along with my port.

I buzzed my hair the first time on my own then I just appeared hairless one day and that was really upsetting for her. She wasn’t even able to tell me that. She just avoided me and had some stutter that was stress-related. As I would get better and worse throughout treatment and the relapse, her stuttering would coincide exactly with when things were not going well with me. She’d get better when I get better.

I would have never thought to include her in that ritual or experience but it turned out to be really empowering for her.

The hair loss was interesting. Who would think to involve their four-year-old daughter in buzzing their hair? When I had my relapse and I knew I was going to lose my hair, I asked my husband to watch the kids while I was buzzing my hair. I was going to throw on my wig, which looks a lot like my real hair.

My daughter comes and sees me with the buzzer in my hand. She said, “What are you doing?” I said, “I took some medicine that’s going to make my hair fall out so I’m going to buzz it off.” And she goes, “Oh. I’ll take care of that for you, mom.” She took the buzzer and shaved my head. And that time, she wasn’t upset as much about me being bald because she made me bald. I would have never thought to include her in that ritual or experience but it turned out to be really empowering for her.

Should I cut my hair or shave my head? Find out how you can cope with hair loss from chemotherapy »

No need for radiation

I had so much chest involvement that I’d have to get radiation all over my chest. There was so much that they would hit inadvertently — my chest wall, the breast tissue, and the surrounding lung tissue.

Because I was only 38 and they’re planning for me to be alive a long time, managing toxicities or second cancers and the potential for that with your treatment is something that your doctors are always thinking about. Some of the pushback is because they’re thinking Hodgkin’s can be really curable even when it comes back.

In Hodgkin’s survivors, we really want to manage the long-term toxicity so that’s not the thing that’s making you the [sickest]. Also, heart disease. Coronary artery disease can happen more if the heart field is involved in the radiation. All these things to think about.

That was the other thing about why they were okay with six months ultimately was because they said, “If you did have radiation, it would have been four months plus radiation. Six months of chemo seems reasonable. Crazy [but] also reasonable.”

Post-treatment scans

In the first two months, it’s like it melted and my cough went away. At about two months in, I started getting a cough and I was on ABVD. Since I’m a runner and I want to be able to run in the future, there was some concern that I was having some Bleomycin toxicity. At the time, we just thought we don’t even want to [take a] chance.

There’s a new trial that had just come out called RATHL and that trial showed that therapy can be deintensified if the two-month PET scan looks good. You can go down from ABVD and drop the Bleomycin, even if the person’s not having cough or side effects. For me, it was like, “Hey, this trial just came out.” “Yeah, you’re having a cough. We’re going to drop it. But not to worry because studies are showing that’s actually just as good as ABVD if you just get AVD.”

I didn’t get repeat pulmonary function testing. They knew the two-month scan looked good. This trial was just published supporting that you could drop [Bleomycin] anyway so why put me through another round of testing?

If you’re interested in being part of a clinical trial, here’s what you need to know »

[My doctor said] it seemed reasonable and worked with me on that. I was really appreciative. Running is my life. It’s my coping skill. I ran through pregnancy. I ran through all kinds of grief and stress in medical school. They knew about that upfront that [it] was a very important aspect of my life and that we wanted to preserve that.

That’s what I did from months two to six. Then I had my end-of-treatment PET scan and it looked great.

Complete remission

I was in complete remission.

We celebrated that first night. The kids sang “Happy No More Chemo to Mommy” instead of “Happy Birthday.”

I remember the visit. My doctor said, “You’re in complete remission and you need to go on a vacation.”

I had my end-of-treatment PET scan and it looked great. I was in complete remission.

Relapse

Initial symptoms of relapse

I wasn’t feeling well. I felt really beat up. I didn’t feel right. Something wasn’t right. I just didn’t trust that things were okay because I didn’t feel okay.

My health really declined over those six months. I gained a lot of weight from the steroids and the more weight I gained, the harder it was to manage further gain. It just spiraled out of control.

I started feeling a little bit of a lump in my neck. I wrote to my doctor at the time that I thought I felt a lump and that was maybe in November. I had my end-of-treatment PET in October. Within a month, I felt a pea-sized lump.

I wish I made an in-person visit, but I emailed and my doctor said, “Let’s just keep an eye on it and if it’s still growing or if it’s still there, then in two weeks, we’ll talk about what to do next.” That was around the holidays and, in my mind, I knew that wasn’t right.

A person who’s just had cancer now feels something really similar in the area right where you already had cancer. On some level, I was like, “This isn’t going to be good.” But I accepted that decision. Let me just give myself two more weeks to enjoy the holidays before I have to face the reality that I’m relapsing. I allowed that timing of things to happen, even though I knew that it wasn’t right [and] that I needed to advocate.

During that two weeks, I messaged my doctor that I thought it was growing. She said, “Okay, let’s get a PET.” But then I got COVID and I really felt quite ill. Fortunately, I wasn’t hospitalized. I was pretty sick with flu-like symptoms [and] high fevers for about seven days so that delayed everything. We don’t want to PET scan right after you get COVID because it can cause a lot of false positives that are actually not cancer. It’s just COVID. It’s very hard to tell what’s what. It delayed my ability to get the PET scan and biopsies. That all got pushed back [for] about a month.

Getting diagnosed with the relapse was tough. My doctor, once the PET was positive, was a fierce advocate for me. We started with interventional radiology with an ultrasound fine needle aspiration, which they don’t usually like in Hodgkin’s. The cells are really big so if you get a fine needle aspiration and it’s negative, you don’t necessarily know: Is it negative because there’s really no cancer there, or is it negative because we just stabbed the tissue next to it and we missed the cancer cells?

The FNA was negative, but we didn’t believe it because of the PET scan. The stuff that was lighting up [in the area that was most accessible] was lighting up the least and the stuff that was lighting up more brightly was deeper in my chest.

I ended up having to get a bronchoscopy with an endobronchial ultrasound-guided biopsy. They put a camera in through your airway and they biopsy through your airway. I was intubated and had general sedation at that time, which was scary because that was the first time I’d been under general anesthesia.

Emotional roller coaster

When I was finally declared no evidence of disease, I took a nosedive into severe depression after the physical recovery started. My counts were starting to come back from my last chemo, no evidence of disease on the PET, felt like I was starting to potentially get out of the danger zone, and then I just fell apart.

I couldn’t concentrate and I didn’t know if it was just the accumulation of all the chemo. Chemo brain is such a broad term that people use, but for me, it was always really a combination of severe sadness and difficulty functioning in everyday life, difficulty remembering things, difficulty doing what I would say, or executive functioning tasks. If I only have one thing to focus on, it’s fine. But when I’m going through an episode like that, give me a list of groceries to get at the store and it’s going to take me twice as long to find my way around. Can I cook a dish while my kids are talking to me? That would be really difficult.

Learn more about how chemo brain feels, how long it lasts, and how to combat it »

When I was finally declared no evidence of disease, I took a nosedive into severe depression after the physical recovery started… I just fell apart.

A combination of that and remembering who I was just six months before. I was a highly functioning person. I felt like it was such a far fall for me. Even though now I’ve done a lot of frameshifting in a more positive way, I was really comparing myself to where I had been. I was so scared that I would never come back to what I was, even though I did.

When I got to the transplant later on with the relapse, I had the confidence of knowing that I could feel that badly emotionally but that I could come back from that and recover.

Emotionally, I hit the floor and that was tough. Lasted a couple of months. I delayed returning to work first because [of] the emotional and neurological issues. I have that muscle pretty well fine-tuned where I know I shouldn’t be taking care of patients because I’m not okay. I’ve been through it so many times with caring for my husband and I knew I wasn’t okay. I delayed it initially to get through all that.

When it became clear that I was relapsing and it was just a matter of diagnosing, I communicated to my work, “I don’t think I’m actually going to be back for a while because I’m pretty sure I’m relapsing.” I kept them updated but it was a roller coaster for them, too.

My doctor at the time ended up leaving the organization where I was receiving care so I changed to another doctor right about the time I started therapy for my relapse. She was really kind about that. She just said, “It just takes how long it takes for you to get better and it’s different for everyone. Try not to be too hard on yourself. You’re also going back to a very different job. Some people have a more physical job. It’s not as cognitively intense, but your job, you’re in charge of people’s lives. You’re making really important decisions. Your baseline of being well enough to go back to work is going to be different than somebody else’s, depending on what you do and how safe it is.”

It just takes how long it takes for you to get better and it’s different for everyone. Try not to be too hard on yourself.

Reaction to the relapse diagnosis

I got to a place where I was starting to feel better emotionally [and] neurologically. Then the relapse got diagnosed and I had to have robotic-assisted thoracic surgery. I wrote a letter to my family if I don’t wake up or don’t come back because I never had surgery this invasive. I remember that being really emotional.

The relapse was a combination of shock and then things moved quickly. I was referred to the local bone marrow transplant center and started having appointments. The bone marrow transplant doctors started working with my hematology-oncology doctor to make a plan. I started therapy pretty quickly because I was feeling so poorly.

Treatment

Brentuximab targeted therapy

My doctor advocated for me to start Brentuximab, which is the therapy that I took as soon as possible because I felt this left-sided upper chest wheezing. I was trying inhaler [and] it’s not doing anything. I was actually ready to take steroids just to make it go down.

Once I got diagnosed, she said, “The sooner you can start therapy, you’ll just start feeling better.” I started therapy pretty quickly so I felt like I didn’t even have time to think about everything. It just happened so fast.

Side effects from Brentuximab

There was a little bit of discussion about [whether it] should be Brentuximab alone versus Brentuximab with ICE, which is one of the regimens that can be used for relapsed/refractory leading into transplant. But my thinking had already started to shift a little bit.

Initially, I felt, “Yeah, slam it with everything upfront.” Then I felt the cumulative effects of six months of that. I was given an option of Brentuximab alone and then re-PET after a couple of cycles to see [if] that worked well enough and if it didn’t, then get something else versus upfront getting ICE plus Brentuximab. I thought, Oh. Brentuximab alone? Yes, please.

I knew it was a targeted therapy, which meant that you’re still going to have some side effects but your hair could continue growing back. I didn’t need a lot of pre-meds before my infusions and that meant I could think better. I actually worked for a couple of months remotely just doing really small things like answering patient emails and connecting with my group. I was able to think pretty well on Brentuximab alone.

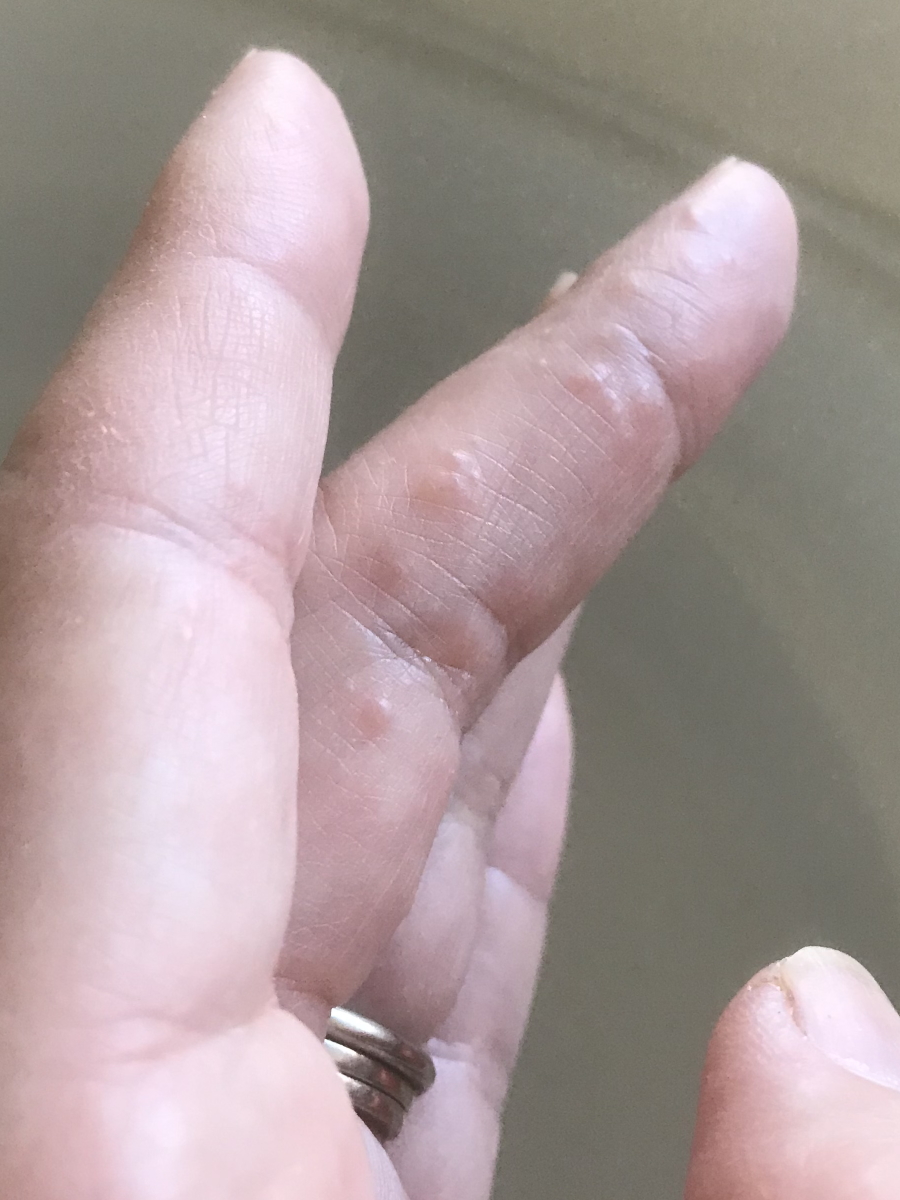

The first infusion that I got, I called my mom on the way home and said, “Oh, this is nothing. It’s like sailing. No big deal at all.” That was after one infusion. I started getting more of the infusions then the hives came on my elbows and I started having really bad joint pain like I’m an old lady. And nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Not a ton of nausea [and] vomiting. Nowhere near the first time, but there was a lot of pooping. I called it “chemo cholera.”

Those are some of the side effects but way more manageable. That was even confusing for my kids because while I was on therapy, they saw me getting better. They were having trouble realizing that this was going to get worse again because I was starting to look so much better healing from the ABVD.

Managing the side effects

I started off with Imodium, then I was taking high doses of Ibuprofen and Tylenol, alternating, and I was doing creams. When that didn’t work, I was doing Zyrtec, an antihistamine. Then we started talking about Prednisone. I ended up on more serious pain medication. I needed that just to get through.

Taking pain medication regularly for a couple of months, even if it’s just [a] low dose, taking it exactly as prescribed, and tapering off of it exactly as you’re told — it’s not fun coming off of it. It’s very uncomfortable. But I was so uncomfortable with the joint pains. By that time, I was getting infusions every week and the side effects were really starting to add up. I just weighed the options and knew that I needed something stronger.

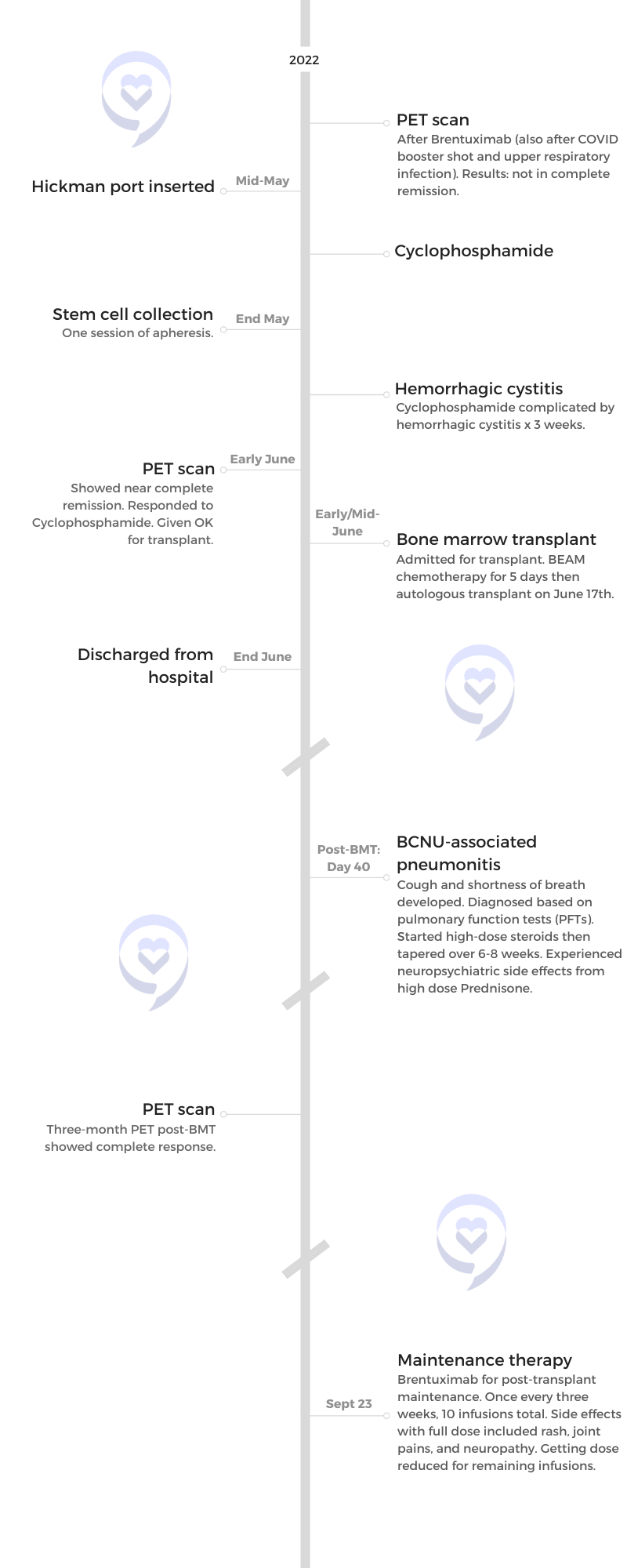

Bone marrow transplant

Single therapy of Brentuximab before the transplant

Three months and then I had to get a re-PET.

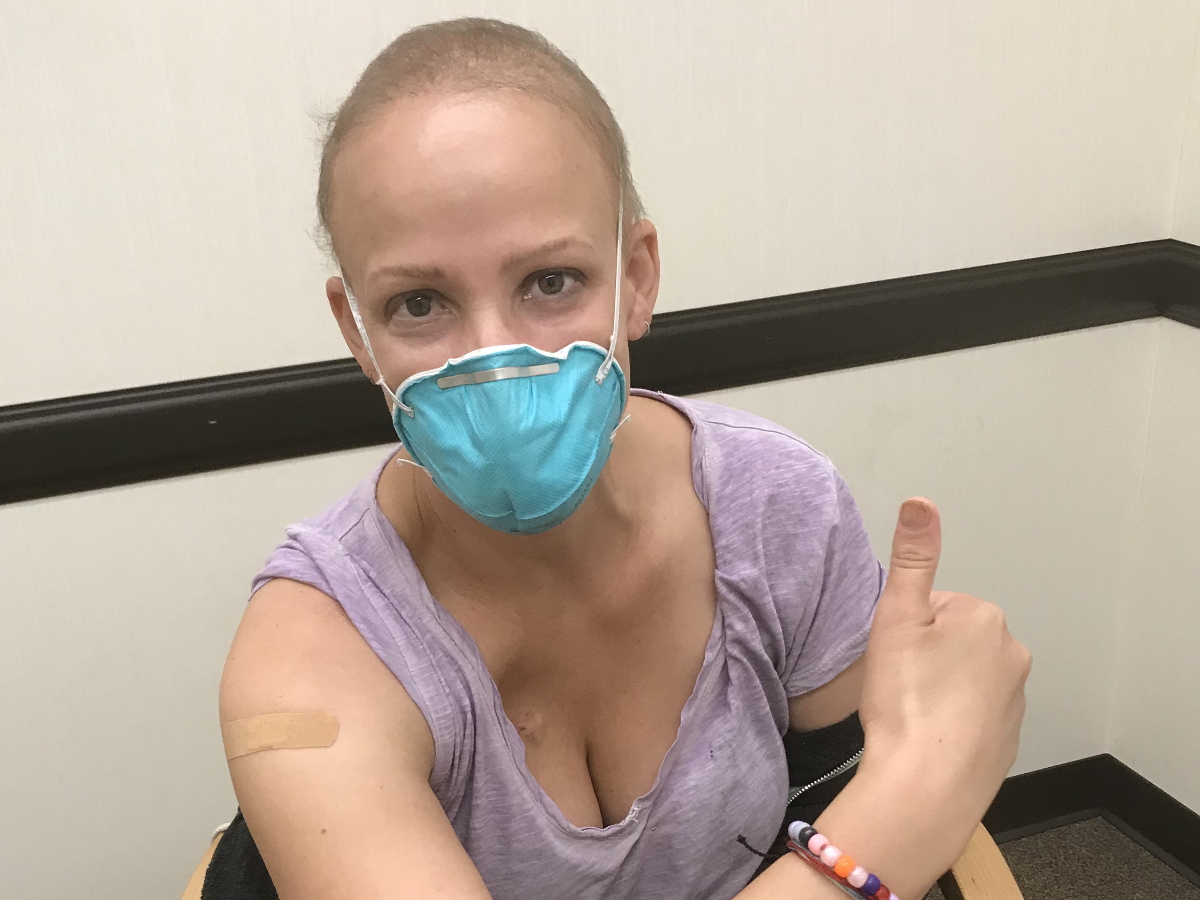

I got my COVID booster on the Friday before my Monday PET and I also had a little bit of a sore throat. My kids had an upper respiratory infection, but I didn’t feel horrible compared to everything I had been through. I wasn’t thinking, Maybe I should let my doctor know that I’m not feeling 100%. I just had my vaccine.

Now I know that they would have said, “Okay, let’s wait on your PET scan for two to four weeks because it’s probably going to show some stuff that may not be anything. We’re really trying to find out: Are you in complete remission or partial remission before you go into your transplant?” Because those are important things that help your doctors to figure out your overall statistics.

I had my PET and it was confusing because it wasn’t no evidence of disease and it wasn’t complete remission. It was questionable partial remission. We came up with a compromise. Instead of doing ICE, there’s a way to collect your stem cells [the] old-school way that uses chemotherapy instead of what most people do now, which is G-CSF injections or Neupogen.

They said, “Because we don’t know and there’s a question that maybe you got a partial response and this is the old way that we used before we did Neupogen anyway, we’re going to give you Cyclophosphamide as part of your cell collection process going into transplant.” I had another huge slug of chemo down at Stanford and that was tough.

I should have gone to the hospital [with] the amount of pain that I was in.

I ended up having my first really serious complication from chemo, which was hemorrhagic cystitis, which is basically peeing blood and blood clots for about two weeks. It was really, really awful. Every time I went to the restroom, it was like having a baby crown. Every single time for about two weeks. Ultimately, I figured out [that] if I just lay in the bath and drink a lot of fluids, then I can just drink and pee in the bath instead of having to go. It was crazy. It was totally crazy.

It’s pretty rare. The thing that’s probably even rarer is someone trying to stay home through that kind of thing. Now that I’m able to step back and look at it, I should have gone to the hospital [with] the amount of pain that I was in and [the] things my family was saying. At one point, my son said, “I think you’re getting better because you’re screaming a little bit less when you pee.” I wished that I had gone to the hospital but in COVID, it’s such a hard thing to figure out. Should you expose yourself to everything in the hospital or not?

Bone marrow transplant process

The transplant was amazing. Even now, I’m in total awe of the whole thing. It was probably one of the most physically grueling things I have ever been through but also one of the most beautiful.

The cards that I gave to the nurses when I left the hospital said something like this felt like giving birth to myself all over again. It was a really emotional, transformational experience and also really scary.

Everybody is exceptionally kind there. My bone marrow transplant nurses were like Mother Teresa. They were so, so nice and the care was outstanding. Everything from the food that you could order on the phone and all the different options. The compassion of the medical team, particularly the nurses, was outstanding.

The transplant was amazing. Even now, I’m in total awe of the whole thing. It was probably one of the most physically grueling things I have ever been through but also one of the most beautiful.

I’ll never forget one night that I was in there and I was just really, really nauseated, totally uncomfortable. This is after I’ve had all the chemo, had my cells going in, and everything coming back. I was so just nauseated and got pretty much everything there was to give for nausea. It was the middle of the night. My nurse said that his other two patients were quiet. He came [into] the room, paged the doctor, [and] confirmed there was nothing else to give to me.

Instead of leaving my room because he couldn’t give me any medication, he got a wet cloth, put it over my head, rubbed my back while I vomited, pulled up a chair and just talked to me, and didn’t let me suffer alone. That’s just one example of countless examples. They’re like doulas. They guide you through the process.

Even when there’s nothing left to give you or nothing left to do, they try heating pads [and] cold packs. “Try sitting this way.” “Let’s get you out of bed.” “Let me help you shower.” Just the incredible level of care and human experience. It feels so awful to feel that sick but people shepherding you through that — such an amazing feeling that I got to know that level of human compassion.

Recovering from bone marrow transplant

When I got home the first day that I was discharged, I thought, Are they really going to let me out of here? Because I’m a hot mess still. They really do try to get you out of the hospital as soon as possible and I think part of that’s just you’ll do better at home. You’ll get up and down more. It’ll be your food, your bed.

I was really glad when I finally got home. But it was hard. I was still really very sick. One of the drugs that I got [in] preparation for my transplant was Melphalan and the nausea [and] vomiting with that drug [were] pretty bad. [And] since I’m already sensitive [to] nausea, I was nauseated for quite a while.

It feels so awful to feel that sick but people shepherding you through that — such an amazing feeling that I got to know that level of human compassion.

Making the trips back and forth from Sacramento to Stanford, which is about 100 miles away, I would sometimes barf out the window. It was tough making those long car trips.

Other people opt to stay in the area and that probably would have been smarter to do. But emotionally, I really needed to come home and start the healing with my family. My kids are so young that they weren’t allowed on the transplant unit. Even during COVID, the number of visitors [is] limited. I needed to go home.

Find out how to navigate the feelings that come along with hospital stays »

Once I started feeling better physically, I had a similar emotional crash after ABVD and I’m still working my way out of that.

I had a lung complication called pneumonitis, [which] can be a delayed chemical irritation in your lungs after chemo and that was difficult to diagnose. I felt like my lungs were shutting down. I had pulmonary function tests that confirmed the case, that there was a really big drop in my lung function from right before the transplant.

I got treatment started very promptly, which is high-dose steroids, and within a couple of days, I was able to breathe much better.

But steroids have side effects. Emotionally, I was manic and reorganizing drawers then I felt really depressed.

Maintenance therapy with Brentuximab

I remember my doctor mentioning it, even the one before who ended up leaving our organization. She mentioned it briefly and I stored it away because I started asking my doctor about it. There was a lot of, “Just wait for that part. Just get through the transplant. Just hold your horses.” But I wanted to know.

My Stanford doctor [and] the transplant team helped to make that decision and talk about a trial that was done or a paper from The Lancet that talked about risk factors at time of relapse. What stage were you [at] when you relapsed? Did you have symptoms like night sweats and fevers? And I did. But it was confusing because I had also recently had COVID and so we weren’t sure if those sweats and B symptoms that I was having were from COVID or they were from my relapse. There was a back and forth just to cover for that, just in case we decided to do the maintenance therapy [with] Brenuximab, which I do okay with.

I always try to be the Goldilocks of patients — not too much, not too little, but just right. It’s a difficult balance to strike.

Importance of communicating with your doctor

It’s very tricky to be a doctor-patient or a healthcare worker patient. You can’t not be who you are or not know what you know. I don’t want to make anybody feel like I’m telling them what to do or telling them how to do their job.

I always try to be the Goldilocks of patients — not too much, not too little, but just right. It’s a difficult balance to strike.

When I first brought up the potential for relapse, what I really felt should have happened right away is, “Oh, there’s a lump? Why don’t you come in soon so I can feel it, document it, and order a scan?” Maybe a more assertive person would have said that from the get-go, but I didn’t. I was still in my phase of what I call trying to be politely ill. I don’t want to offend anybody or make anybody else uncomfortable, even though I’m the one with cancer. I still have to work through some of those when dealing with behaviors that make me feel uncomfortable and try to give that feedback to my team.

Cancer was just terrifying since the beginning. Part of what I’ve been dealing with, even now just trying to communicate with my medical team, is that sometimes I feel the irritation from questions I’m asking. I’ve been told, “Just email me if you have any questions,” so that’s what I do. I have questions so I email.

I can feel that they’re busy and maybe slightly irritated [from] the tone [of] some of the messages — that’s what I’m projecting onto it but that’s how it feels. I just think, Why am I even dealing with that? Why should I even have to think about [it]? I’m the one with cancer. I don’t want to need healthcare professionals in my life. I’d be so happy to stay away from hospitals. But you do, you have questions.

I found that I have to just get out of my comfort zone and be really honest with my team. “Hey, when you said this, it made me feel this way. It hurt my feelings,” or “It made me feel scared when you said that,” or “I felt that I couldn’t ask questions because of the way that you spoke to me.” I’ve had some of these exchanges and they’re extremely uncomfortable. But I think I’ve been able to say them in a way that conveys that I love my doctors and my healthcare team, and I also need to be able to ask questions about my life.

There were a couple of nights where I just felt so sick, really at the brink. Then you come out of it and you get better. But my perspective was I got a second chance. This is my life. I need to stop being afraid to ask for what I need. It’s my one life.

I know that sounds crazy but that’s how I felt in my most vulnerable moments in the dark of the night when I’m just thinking about things.

Feeling like you’re on the “wrong” side

There have been times that I have actually been straight out called anxious or labeled anxious in person. At one point, my doctor said, “You know, Dr. So-and-so and I have talked and we think you’re anxious.” That to me was so hurtful because I would have loved to be asked how I felt. “How are you feeling about things?” Anxiety might have been one of the emotions, but I would have also said hopeful and excited for life and the opportunity to get treatment and a lot of different things but I’m working through it.

Being told how I felt, that happens to people over and over again. It’s happened to me a lot of times. It’s really painful emotionally and I think my fear deep inside was I feel like my doctors don’t like me and I feel like I’m really starting to piss them off. If they don’t like me and I’m one of their most annoying patients, they’re going to start avoiding my room or the person that’s tasked with saving my life won’t try as hard to think about my case or advocate for me.

I know that sounds crazy — I certainly would never practice that way and, in reality, I don’t think that my doctors would do that — but that’s how I felt in my most vulnerable moments, in the dark of the night when I’m just thinking about things. Geez, I think I’ve really irritated this person. What if they don’t take me seriously or try as hard as they can to save my life because they don’t like me?

The power inequality was something that I always really felt and I think that non-health professional patients would find that surprising. You’re both doctors, but I’m not the one in charge holding all the cards. I just have to accept this treatment and the recommendations.

After my relapse and recovering from my relapse, I’ve been trying to become more emotionally empowered, which means asking for what I need, saying when something makes me uncomfortable, [and] taking care of myself — my body, my mind, [and] my needs.

I saw anxiety, anxiety, anxiety. I thought to myself, Yeah, I’m anxious. I’m a doctor-patient and this is a really awesome place that’s super amazing, high-level care known all over the country, all over the world. There have been experiences like this all throughout my cancer where I have to check the information or check the provider and make sure that’s correct. Of course, I feel on edge — anybody would. It’s your life. Then it’s always documented all over my chart, really thoroughly, how anxious I am. That to me just doesn’t feel fair. I’m sure other patients probably feel that way, too.

I’ve been trying to become more emotionally empowered.

The impact of notes on a patient’s chart

It’s tough. The transparency of note writing is a good thing overall because I do feel that it leads to more objective, less passing judgment on the patient and more the patient states they have anxiety or they need to document the anxiety because there are certain medications that are tied to it. I think that’s all helpful.

But those things are absolutely erroneously carried forward sometimes. I’ve had patients tell me, “Somebody wrote diabetes in my chart years ago and now it’s everywhere. I don’t have diabetes. I do have peripheral neuropathy and they don’t really know why I have it, but it’s not from diabetes. Can you figure out a way to get that expunged from my chart?”

It’s real for patients. Somebody writes something and maybe an insurance company sees and that impacts their decision-making. Or in the middle of the night, it could be a medication in an ER somewhere. [There are] a lot of potential ways that it could impact your care.

Clearing up communication lines with your doctor

I wrote to my doctor and said that I think there’s something wrong with our communication. I really want to be your patient. I respect you. Your words and your tone lately make me feel like you don’t like me and that I’m really irritating you. And that’s terrifying from your oncology provider who’s supposed to save your life. It’s terrifying to feel like they’re irritated with you or pissed off at you. If there’s something broken, let’s fix it, and just tell me what it is because I will be happy to adjust how I express what I need. I don’t want to irritate you. I want your job to be easy and I want my care to be easy.

I felt that the right choice was coming out to this person and saying that and also saying maybe it doesn’t have to do with me at all. Maybe you don’t think about me at all after you email but just so you know, this is how it comes across. Maybe you just let it go and moved on to the next thing. Maybe you don’t even think twice about me after this. Maybe it wasn’t how you intended it, but this is how it came across.

Right after I wrote it, I was terrified. Oh my god, why did I do that? But my provider wrote back to me and said, “I’m so sorry. I didn’t intend it to be that way. We need to actually talk face to face or on the phone.”

Sometimes with electronic communications, it doesn’t capture [the] tone. Doctors are super busy and rushed so sometimes what they feel is just being direct and brief, even if it’s a little bit salty, can be really painful for the patients. I get it on both ends.

This is somebody that I work with and so I feel that I need to look into why the relationship is broken right now or how it got broken. And also the very real fear that if I do decide to go to somebody else, even though this would be [the] first change of my initiation, it could be viewed as doctor shopping. Once you get labeled an anxious doctor shopper, it’s really bad.

I decided [to] be human about it and try and fix it. But that took a lot of courage and it’s taken me a year and a half of battling cancer to get to that point. And it still was highly uncomfortable. Not everybody’s going to be able to get there but some people might.

I think one of the reasons I felt so emboldened and supported was [that] I talked to my bone marrow transplant support group the night before. I told everybody, “I don’t know what to do. How do I figure this out?” They all just said, “No, no. You shouldn’t even have to be thinking about, ‘Does she like me or not like me?’ Why are you even thinking about that? You need to either say something or change.” I decided that for me, the right option was to say something. But other people might want to change if they feel like it’s too uncomfortable.

Words of advice

I’m still recovering and recovery is not a linear process. Wherever you are, it’s okay. If you feel awful one day, try not to let it snowball into, “This is how I’m going to feel forever,” because you will feel better. Some days you won’t. Some days you need to just [lie] down. This is not the body I had six months ago.

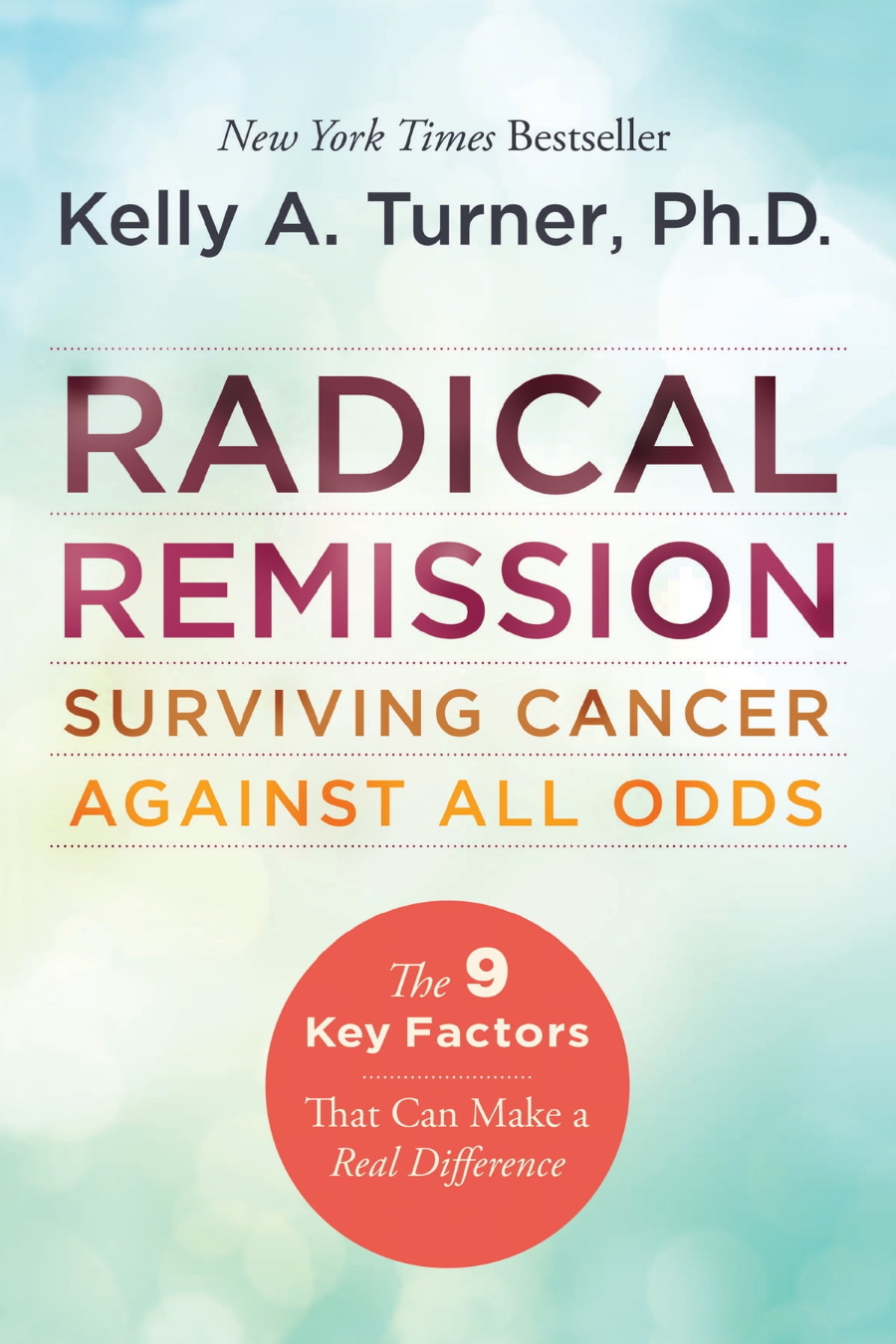

I also found, in helping support my body through conventional allopathic treatment, that a lot of additional things have been really helpful like books about mindset and mental toughness. Since I finished my therapy, I’ve been doing [a] really strict plant-focused diet, juicing, exercising, and support groups — like a comprehensive wellness plan to help me heal. I think there’s this vibe that when you get no evidence of disease or you’re cured, it’s like, “Okay. Be happy. Move on now.”

I feel like I am so broken down right now. How am I going to get better? There are tools out there. There’s something called Wellness Within in the Sacramento area but there are probably similar things in many geographic areas. They help you ease back into exercise, diet, mindfulness, [and] meditation to help the intrusive or trauma thoughts that you might have from your transplant or treatment experience. That’s very real.

I’ve had to be very aggressive about taking care of myself and try and push out that feeling that I get from other people. “Are you all better now?” I don’t even know what to say to that. I’m better. I’m a completely different person than the last time we spoke.

You’re not alone. I’d be happy to speak with anyone who might need help. I just feel really lucky to put it all out there.

Recently, I’ve been listening to this book called Can’t Hurt Me by David Goggins. He says, “Your story is your power. Own that shit.” This is one of my first steps and I was really scared to tell my story. There’s this culture in medicine that you just put your head down and keep going but I don’t think I can do that anymore if I want to fully heal. So I’m making my story my power and owning that shit. I’m really owning it.

Recovery is not a linear process. Wherever you are, it’s okay. If you feel awful one day, try not to let it snowball into, “This is how I’m going to feel forever,” because you will feel better.

You’re not alone.

Inspired by Sam's story?

Share your story, too!

Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Stories

Jessica H., Hodgkin’s Lymphoma, Stage 2

Symptom: Recurring red lump on the leg (painful, swollen, hot to touch)

Treatment: Chemotherapy

Riley G., Hodgkin’s, Stage 4

Symptoms: • Severe back pain, night sweats, difficulty breathing after alcohol consumption, low energy, intense itching

Treatment: Chemotherapy (ABVD)

Amanda P., Hodgkin’s, Stage 4

Symptoms: Intense itching (no rash), bruising from scratching, fever, swollen lymph node near the hip, severe fatigue, back pain, pallor

Treatments: Chemotherapy (A+AVD), Neulasta