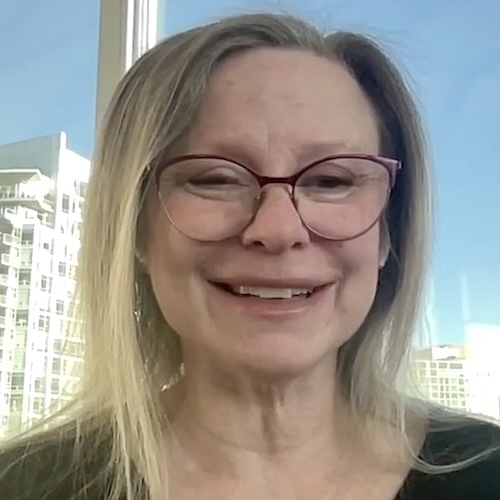

Abigail’s Stage 4 Metastatic Breast Cancer Story

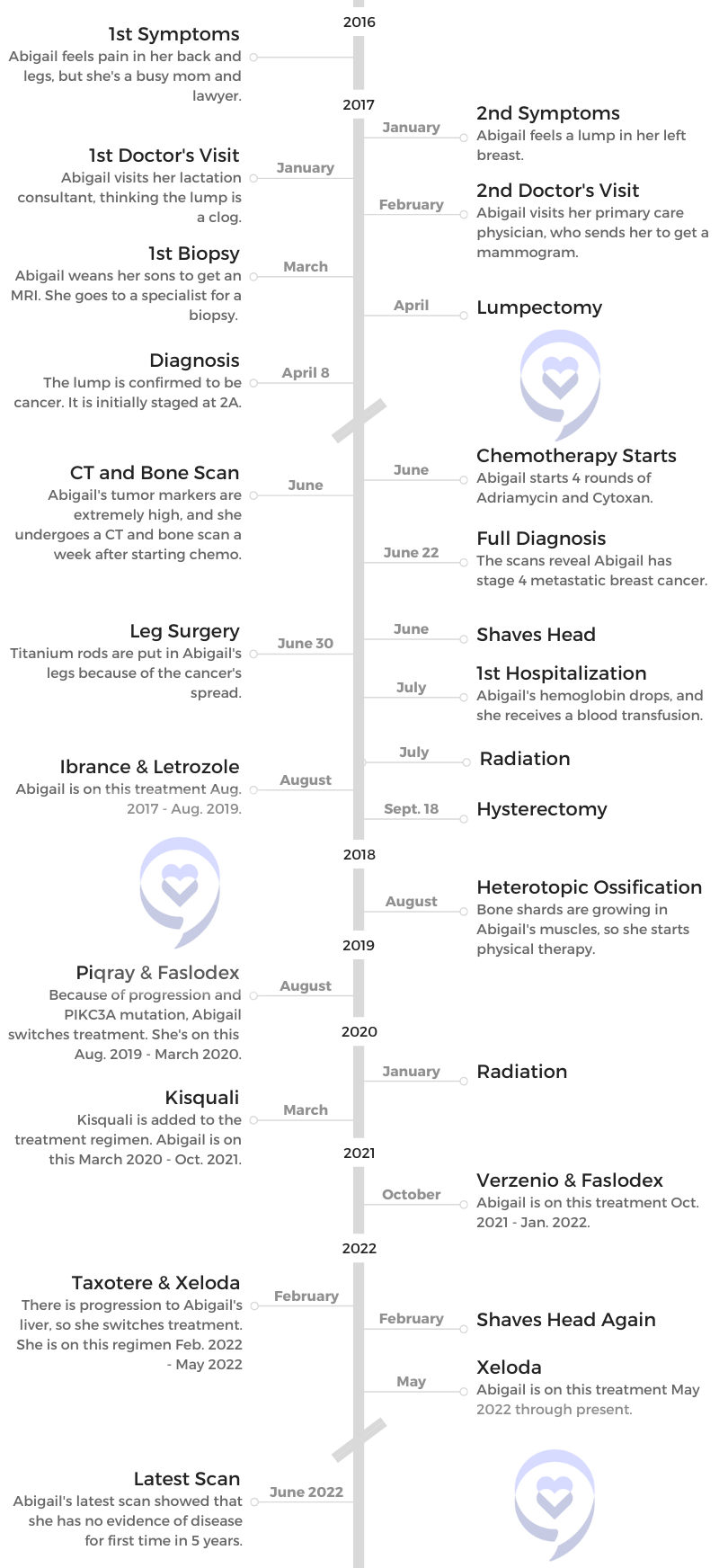

Abigail was a busy lawyer and mom of 2 when she found a lump in her breast. After her first mammogram and a biopsy, she was diagnosed with breast cancer.

What was originally thought to be stage 2A turned out to be stage 4 metastatic, meaning it had spread throughout her body.

Abigail talks about parenting with cancer, the transition from a busy career to going through treatment, patient advocacy, and the exciting breakthroughs in treatment.

Thank you for sharing your story, Abigail!

- Name: Abigail J.

- 1st Symptoms:

- Back and leg pain

- Lump in left breast

- Diagnosis (DX):

- Metastatic breast cancer (MBC)

- Node negative

- HER2-low

- PIK3CA mutation

- Staging:

- Initially staged at 2A

- Stage 4

- Tests for DX:

- Mammogram

- MRI

- Biopsy

- Treatment:

- Lumpectomy

- Chemotherapy

- 4 rounds of Adriamycin & Cytoxan

- Hysterectomy & oophorectomy

- Ibrance & letrozole (8/17 – 8/19)

- Piqray & Faslodex (8/19 – 3/20)

- Piqray, Faslodex & Kisquali (3/20 – 10/21)

- Verzenio & Faslodex (10/21-1/22)

- Taxotere & Xeloda (2/22 – 5/22)

- Xeloda (2/22 – present)

- 1st Symptoms and Testing

- Breast Cancer Diagnosis

- Processing Cancer and Finding Community

- Undergoing Treatment

- Different Treatment Options

- What were your side effects from treatment, and how did you manage them?

- CDK4/6 inhibitors

- Switching to Piqray

- Research and fundraising

- The future of treatment

- Patient advocacy

- The importance of clinical trials

- What are the differences between genetic and genomic testing?

- Using genomic testing to plan for progression

- Experimenting with treatment

- How Treatment Affects Life

- Reflections

- Different Treatment Options

- More Metastatic Breast Cancer Stories

This interview has been edited for clarity. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider for treatment decisions.

1st Symptoms and Testing

Introduction and Symptoms

Who are you outside of cancer?

I style myself a recovering lawyer. I have had a legal license for 20 years. I’m a mom. I have 2 boys — they are now 7 and 9 — and a husband as well.

I have a very supportive husband. He’s had to make a whole heck of a lot of adjustments since [I went] from healthy to not so healthy. He has weathered all of those adjustments with a lot of grace, which I appreciate.

I love the Enneagram. It’s is a personality type [or] way of understanding motivations. I very much resonate with type 8, which is sometimes called the challenger. I tend to challenge systems and definitely have learned a lot in the last 20 years about being an advocate. It’s kind of in my DNA. If something is wrong, I have to fix it, which is challenging at times with the amount of energy I have during the day.

Justice is something that’s very important to me. It’s probably why I ended up going to law school. My husband is black. He’s from Jamaica, so I’m understanding a whole lot more about the experience of people who are marginalized. That really pisses me off. I tend to get into the weeds with people about fixing those things.

What led to that first diagnosis?

I was 38 when I was diagnosed. Typically they don’t begin mammograms until 40. Because my mother is a breast cancer survivor, I could have gotten mammograms beginning at 36, but I was pregnant and nursing.

The mammogram itself doesn’t see as well into the breast when the milk is there. It clouds the image, so it wasn’t recommended by my primary care physician. Looking back, in 2016 I began having a lot of pain in my back and in my legs. Now I understand that was the metastasis that had spread to my bones.

I was a mom. I was tandem breastfeeding at that point. My kids were 1 and 3. I had a million things going on. I was running my law firm. You don’t prioritize yourself, I think, as a mom. [You don’t prioritize] your health, that sort of thing. It’s so important for us moms to listen to our bodies, to go to the doctor when things are wrong, and to ask the questions that need to be asked.

I don’t know if things would have been different if I had been diagnosed sooner. Certainly, by the time I was diagnosed, it had progressed to a very significant disease load. I don’t know if things would be different if I had said something sooner. Anyway, at the end of 2016, I was in a fair amount of pain.

Finding a lump in the breast

Then in January 2017, I felt a lump in my left breast. Because I was tandem nursing and pumping every 2 to 3 hours and had been doing that for 4 years, I was certainly very familiar with my breast tissue. But because of all of the nursing, I also had more tissue than I would normally. Even though the lump was relatively close to the surface, I didn’t really fully grasp what was going on.

I thought it was a clog and went to my lactation consultant. Interestingly enough, the cancer in my body happened in my breast exactly where I’d had clogs, and the same thing happened to my mom. The areas where the tumors were that they found when she had her DCIS diagnosis almost 20 years ago now were exactly in the places where she had clogs.

Definitely something to think about if you’re a nursing mom. Pay attention to those areas of your body and make sure that your doctors are paying attention to them as well. No one really treats your breast when you’re breastfeeding.

Your PCP might know something. The pediatrician knows some things. The OB-GYN knows some things. There’s not somebody who’s really talking about your breasts, especially when you’re nursing, except for lactation consultants. Not every medical practice has those.

Testing for Cancer

Is there a way to have a baseline to understand changes happening?

Absolutely. It’s so important to understand that. With lactation consultants, you would want to see an IBCLC, International Board-Certified Lactation Consultant. There are different certifications, but that’s the most important one that has the most medical knowledge.

Those professionals are so important, even with things like latching and different things as you go through your breastfeeding journey. Having that resource is so important. I had that.

We were also part of a milk-sharing organization, so we were able to share about 25,000 ounces during the 4 years that I was nursing and pumping. Ironically, the very first person that got milk from us was someone who had been diagnosed with breast cancer while pregnant. She literally had her baby and was wheeled into the chemo suite. She was unable to breastfeed, and everything just came full circle.

What was that feeling of being able to help someone who wasn’t able to breastfeed?

We had to go through fertility treatment to get pregnant. In a lot of ways, my breasts did what they were supposed to do when the rest of my body didn’t want to. I had a lot of hormonal imbalances that we were able to correct with medications. We didn’t have to get IVF or any of those things, but we struggled to get pregnant.

In a lot of ways, my breastfeeding experience was really redeeming in that my body was doing what it was supposed to do, and it was really doing what it was supposed to do. I had an overabundance of milk, and it was something that was a huge part of parenting. We had to adjust once they were weaned because everything could be fixed by saying, “Let’s nurse.” While tandem nursing, I got to see my boys just bond so tightly because they were nursing at the same time.

I don’t know [if] there’s any experience as good as meeting somebody who was just so grateful for the gift of something that was easy for me. A lot of the children that got the milk from our organization were children who were adopted. A lot of them were drug addicted at birth, and that nutrition — what we called “liquid gold” — was still very important to them.

We didn’t supply the NICUs because we didn’t pasteurize or do any of the things that the larger organizations do. I would take my bags and hand them to someone else. It was an amazing time. I was so grateful to be able to help as many people as we were able to during that time.

What happened at the lactation consultant?

She touched the area and said, “It’s probably nothing.” This is something that was consistent across the medical providers that I saw. “But I’d really like you to just go to your primary care physician and ask her.”

I had actually picked a primary care physician who not only personally tandem breastfed her children, but also had an extra lactation certification. Again, there aren’t those doctors that treat you when you are nursing. It took a bit for me to find somebody, but I had.

This was literally my second appointment with this particular doctor. She said, very similarly to the lactation consultant, “95% sure this is absolutely nothing, but since you’ve never had a mammogram…” Because of my mother’s history of cancer, she sent me for my very first mammogram.

How genetic testing for cancer has changed

My mother had breast cancer when they really only knew about the BRCA1 and 2. She did genetic testing immediately because [she was very concerned about her daughters]. I’m the oldest of 6, and there’s 3 girls. Because she was BRCA negative, we thought, “Oh, we’re in the clear.”

In 2013, they updated the panel of genes that they know to look for to 40. Now, almost 10 years later, we’re at 92. If anybody has had genetic testing prior to 2013, you really should get it redone. Honestly, my mother doesn’t remember being prompted to redo it in 2013, [so] she didn’t.

We later found out in my breast cancer experience that we carry a germline mutation ATM, literally like you get money from the ATM. ATM is part of your DNA that’s responsible for repair. If there’s a mutation in the part of your DNA that’s supposed to repair mutations, clearly that can be an issue. We didn’t find that out until later.

I am so grateful. For a lot of young women under 40, their doctors say, “You’re too young to get breast cancer. It’s probably a cyst; it’s probably this. Don’t worry about it.” Instead, my doctor said, “Let’s double-check.”

Mammogram appointment

I went for that very first mammogram appointment. They were very unhappy with me because, of course, as soon as they squished my breast, milk went everywhere. The machine [was] covered in milk. They did a mammogram, and they did a diagnostic ultrasound.

I didn’t really connect to how serious it was. The radiologist came in and wanted to do a biopsy right then. To me, I was like, “Oh, you just want to follow up right now.” My doctor had said that she wanted me to go to a specialist if they wanted to do a biopsy. The specialist that ended up doing my biopsy was both a breast surgeon and a radiologist. She was able to do all of it and then did my surgery.

That was my first experience leaving somewhere against medical advice. Looking back, the social worker came in to talk to me, [and] there were like 12 people that talked to me before they let me leave. I think they thought I wasn’t going to follow up on it. I think they thought maybe I wouldn’t take it seriously.

I’m pretty sure they knew pretty definitively right then that it was something very serious. I was just like, “No, my doctor told me to do something different.” Because I tend to be a bit stubborn when I decide I’m going to do something, I left.

That was a Thursday. The following Monday, I was in the surgeon’s office getting a biopsy, which was a very interesting experience. I’m very thankful my husband went with me.

I got a primary care physician [right] after we got married. I’d never had a primary care physician. I went to urgent care if I had something serious, and I had my OB-GYN that I went to every year. I really just didn’t engage with the medical system all that much. Thank God I was healthy.

My first introduction to medical things was the fertility experience, which was terrible because it was so emotional. It was invasive, and having vaginal ultrasounds every other day for weeks on end was so not fun.

I think one of the big things that was interesting about the biopsy experience is it was done in my doctor’s office, so I didn’t have to go to a surgery center or anything like that. It was ultrasound guided, so I was lying on the table fully exposed, which then was kind of an issue. Now it’s totally not an issue.

There was a person holding the ultrasound wand, and then the doctor had [something] like a long needle with a little grabber thing on the end, where it sounds like a click when they grab the piece of tissue. There was some pain. They used lidocaine to numb the area, and lidocaine shots are not fun to get either.

I felt so vulnerable, probably for one of the first times. [I was] in a doctor’s office, doing [the] procedure right there, where I hadn’t had time to prepare. All of the other testing that I had, somebody explained it to me, and then I made the appointment. I had time to assimilate to what was happening.

This was like, “No, we need to do this biopsy right now.” Oh, okay. Then I leaked milk and blood from the site of the biopsy for about a week afterwards. She had to biopsy a couple of my lymph nodes. The lymph nodes turned out to be full of milk. Not cancer, just milk.

I got to watch on the ultrasound screen as she was doing it and she narrated. It was a very different experience, different from anything that I had ever experienced previous to that. I think I was still in denial at that moment.

My father-in-law just passed away, but my husband and I had cared for him. On our third date, I met him in the nursing home. He had just transitioned into a nursing home. My husband had been his caregiver as a young professional for about 10 years before he went into the nursing home. He had 3 strokes.

I’m so thankful that my husband was much more in tune with, “Okay, this is serious. Yes, we need to do this right now.” I had meetings. I had client meetings, and I wanted to leave. He was like, “No, no, we have to do this now.”

He was very good at knowing that it was serious enough to do something. I think I was a little emotionally disconnected from the experience at that point. Mostly because I had no idea what was going on.

Breast Cancer Diagnosis

Testing Results

Insurance issues and waiting for results

This was all [of] January, February, but it was April 8th of 2017 when I went back to get the results of the biopsy and they confirmed that it was breast cancer.

Yes, it took a while. One of the reasons it did was because my insurance company was only contracted with one lab, and they were significantly backed up. It was across the state, so there was mailing things back and forth and all of that.

One of the very big lessons I learned right at the beginning was it is not our doctors that run our medical care; it is the insurance companies. [I had to understand] early on what my insurance covered, what it didn’t, and how we had to handle the things that insurance didn’t cover. Fighting with my insurance company — it seems like that’s a full-time job in and of itself, because insurance is ridiculous.

When did you realize this was something more serious?

April 8th of 2017 was when we found out it was breast cancer. I think then, we still thought [I would] go through treatment and be done. I had my mother’s experience to compare with. She is amazing and worked all the way through chemo and radiation and everything else. She had a double mastectomy and did all the things that you need to do.

My mother still [has] no evidence of disease now, almost 20 years later. I had her experience to think about. We really thought in April of 2017 that it was going to be a situation where I went through treatment, and then we could put breast cancer in the rearview mirror.

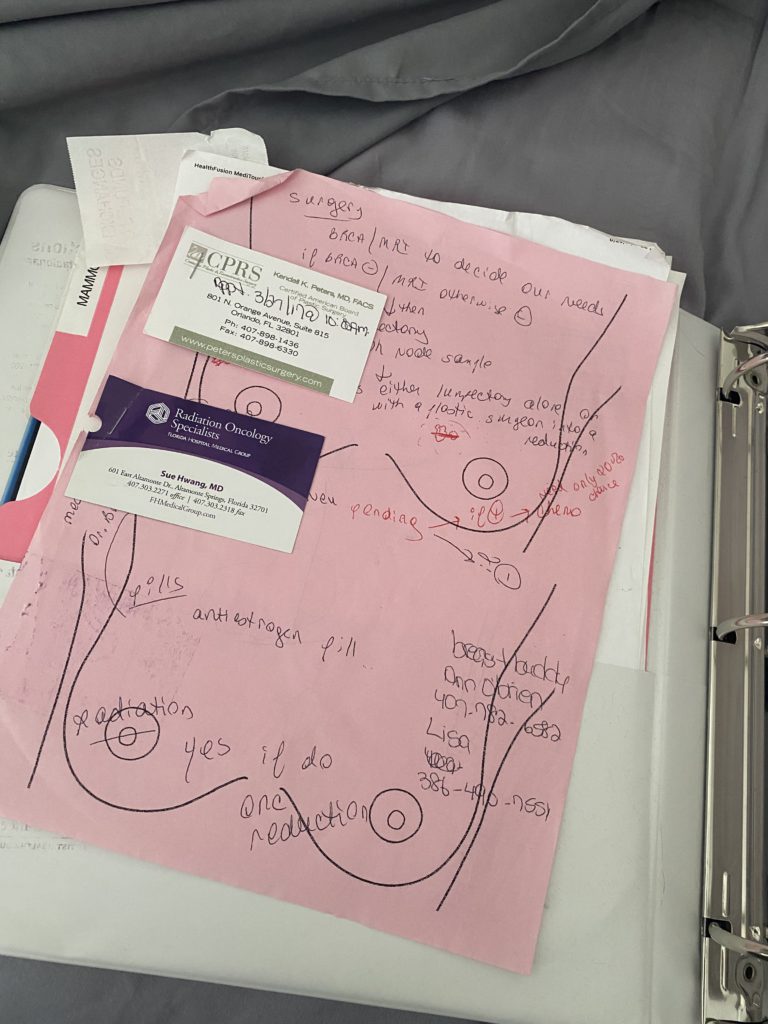

When we found out it was cancer, I left that appointment with an appointment with the medical oncologist, an appointment with the radiation oncologist and plastic surgeon, etc. I had all these appointments to learn about [and] all of the people who were going to be on my team.

I am so thankful that my introduction to this whole experience was [with] someone who said, “I have other doctors I work with very closely. We text each other.” She was texting different doctors to get me in the next day and to talk about treatment options. How amazing!

Genetic testing

The only fly in the ointment, looking back at that initial experience, is that we did genetic testing, but she only did BRCA1 and 2. Here we go again. My mother didn’t get retested, and then this surgeon was only looking at BRCA1 and 2 [and] did not do the full genetic panel.

I understand that it is hard sometimes to get those things covered by insurance, especially when you’re at the very beginning of these breast cancer experiences. Now when I talk to newly diagnosed people or people who are beginning the process, [I tell them] to insist on the full genetic panel, because BRCA1 and 2 are not the only genes that are associated with breast cancer. There are now 93 that they look at and that can change your treatment.

There’s literally an algorithm where they plug in all the different details. Your risk changes when you have cancer that’s associated with a genetic mutation, which is still only 12% of breast cancer. The vast, vast, vast majority of breast cancer has no genetic or discernible basis for it. Our genes just go haywire, or our cells go haywire at some point.

Being connected to other patients

We went into all of the appointments. I remember the radiation oncologist literally spent 2 hours with us, [and] the medical oncologist spent about an hour. All the doctors were so kind and caring, and it was a good introduction to something terrible.

I had my lumpectomy. We decided on a lumpectomy versus a mastectomy. Legally, an insurance company is required to cover a mastectomy if the patient wants it, as well as reconstruction. No insurance company can refuse to cover those things. My doctor was like, “All of these options are yours.”

She also connected me with a couple of her patients who had different surgeries, which I thought was amazing. I haven’t heard of other doctors doing this, but she connected me with somebody who had a lumpectomy, somebody who had a mastectomy, and somebody who had a double mastectomy. That was very helpful because I could compare and contrast their different experiences.

How did you decide which option to pursue?

There’s always pros and cons. Everybody is an individual. My mother had a double mastectomy and then did reconstruction. She had a couple of issues where they had to go back and redo things. One was a whole surgery where she got the scar tissue tightened up, and they had to go in and loosen it.

Honestly, my biggest issue at that point in time was recovery time. I didn’t want to have to have multiple procedures. Typically, when you have reconstruction, they put an expander in. Then you go in over time, and they inject more and more saline into that expander. You’re actually stretching out the skin to make room for the implant. Then you have surgery to put the implant in. The whole reconstruction process can take up to a year.

At the time, I opted for an oncoplastic reduction because we didn’t know I was stage 4 and we thought this was going to be an experience [of] go through it, be done, and it would be in our rearview mirror.

They did the lumpectomy to remove the cancer. They took tissue from my right breast to fill in the hole, or the divot, because it was a pretty big area that they had to remove. Then I got a lift and all of those fun, good, nice things to have everything look aesthetically the same.

That was important to me then: the aesthetic, how much I would have to be in various surgeries, how long it would take. I really wanted to be finished as soon as humanly possible with the medical side of things, because I thought, “Hey, I got to go back to work. I got to get back to doing the things that we’re doing.”

Preparing for the lumpectomy

I had my lumpectomy in June of 2017. It was pushed off a little bit because that particular surgery, there were only 2 plastic surgeons that knew how to do it with my surgeon, and I had to dry out my milk. My doctor handed me a paper with 2 or 3 things to do, and she said, “In about a week, you’ll have no more milk.”

I had been nursing and pumping every 2 to 3 hours for 4 years straight, and it took a lot longer than 1 week for my milk to dry up. One of the things that they needed to do was do an MRI to be sure that there was no cancer in my right breast. We had to get the milk out of the way so those images would be effective and reliable.

Scans and recovery from lumpectomy

I hadn’t had a lot of scanning, but I get PET scans every 3 months. I’m radioactive for at least 24 hours, depending on which isotope and the half-life and all of that. I typically have to stay away from my kids overnight after a PET scan because they don’t know how radiation affects a growing body.

[According to] the picture that they pulled out, the lumpectomy went great. It was a 7-hour or something surgery. I got to go home the same day. It was a great recovery. It was a big change. I went from DD to A. That was a very big change. I was normally an A, almost a B cup. Nursing definitely gave me more tissue than I had normally.

That was a big adjustment, too. Clothes fit differently. You have to wear those awful compression garments for the first [couple of] weeks. It was a big adjustment, but I was still working, still trying to have as much normalcy as possible.

Receiving the Diagnosis

When you received the diagnosis, what staging and details were you given?

My doctor was perfect for me because she was very direct. There wasn’t a whole lot of packaging or hemming and hawing. It was, “Okay, it came back. It’s breast cancer. It’s hormone positive, strongly hormone positive.” At that point, we didn’t have the HER2 status because they had to do the extra testing.

I still have the paper where she drew where it was. I had a tumor and then an empty spot, and then it would look like the cancer was developing a second tumor. It was kind of this weird, almost 2 tumors. At that point, she said most likely I was stage 2 because of the size of the tumor.

At that point, I had not talked about any of the other symptoms I was having. There wasn’t any sense that it had spread anywhere at that point. When we did the lumpectomy, they took 4 lymph nodes.

This is one thing that I learned from my mother. When they do lymph node dissections and they take 26 or 30 lymph nodes out of your body, that compromises your lymphatic system in such huge ways. My mom is a physical therapist. At that point, they were already going to do chemo, and she said, “If you take all those lymph nodes, will that change my treatment plan?” They said no, and she said, “No, thank you.”

Node negative

They injected dye around the nipple in the 4 quadrants. I think it was an ultrasound, or it might have been a different type of imaging. They watch to see the first 4 lymph nodes that the dye went to. Those are called sentinel nodes. Those are the first lymph nodes that would be processing any kind of fluid that came from the breast area.

They took those 4 during my surgery, tested them, and they were determined to be node negative. The typical spread of cancer is from the breast through the lymphatic system into other areas of the body. In about 5% of us — of course, I always fall in these weird percentages — it has spread through the blood before it ever really recruits the lymphatic system. Nobody knows why that is.

Statistically and generally, if you are node negative, [typically] doctors then say, “Okay, you don’t have to worry about the cancer having metastasized.” Because I was node negative, they initially staged me at 2A.

Then they sent off the tumor cancer tissue from my lumpectomy to have genomic testing done. I talked about genetic testing. That’s your DNA, your blood, and what you get from your family. Genomic testing is to look at the characteristics of the cancer to see what kind of mutations it has, etc.

Oncotype test results

It’s called an Oncotype test. There’s Oncotype and MammaPrint. They’re basically the same thing, just 2 different companies. They’re able to score, based on your different markers, your risk of recurrence.

My risk of recurrence came back in the gray area, which is super weird, knowing now that I was already stage 4 at that point. At the time, the gray area for me at my age was 27, and 25 to 30 was the gray area. That’s no longer the gray area. Now over 25 is recommended for chemo. They keep learning, which is so good.

My doctor said I wasn’t at 30, which would have made me in the high-risk area, but his personal, “definitely get chemo recommendation” began at 25. Because I was 27, he said, “You should consider chemo.” The report that we got said if I did chemotherapy, it would reduce my risk of recurrence by a little over 20%. For my husband and I, that was enough of a percentage that it made sense to go through chemo.

We scheduled chemo, and that was Adriamycin and Cytoxan. Adriamycin is often called “the Red Devil.” I would do 4 rounds of Adriamycin and Cytoxan and 12 rounds of Taxol and then radiation. That was the treatment plan.

The nurse in my doctor’s office made a mistake and checked the box for them to check my tumor markers at my first chemo session. Tumor markers are various proteins that are given off and are in the blood when cancer is spreading. It was a mistake. It’s not standard of care. A lot of doctors don’t even look at tumor markers.

»MORE: Read patient experiences with doxorubicin (Adriamycin) chemo

Blood work, scans, and a strange phone call

In June, I had my first chemo session. My doctor called me the day after and said, “There’s something amiss with your blood work. We want you to do a bone scan and a CT scan.” I was hopped up on Benadryl and all of the other pre-meds they give you. Again, I didn’t freak out. I was like, “Okay, sure. More tests. More scans.”

I had asked about the PET scan. He said, “It’s hard to get them approved by insurance, but we’ll do it if you want it.” He didn’t seem very concerned about doing scanning, so I was like, “Oh, okay,” and didn’t push it. I don’t not push it anymore, because I think my intuition was telling me we needed to get more information.

I went in for the bone scan and the CT scan. It was a whole day at the hospital. I vividly remember having client consults, drafting pleadings, and doing all these things from the waiting area. Then we got the call June 22nd of 2017, and the nurse who called said, “You just need to come in. It doesn’t matter when. Just come.”

I was in the middle of preparing for a hearing and was totally distracted. I called my husband and said, “I had a weird phone call. They’re not even making me make an appointment. You don’t need to go. I’m sure it’s nothing.”

Thank God my husband had the presence of mind, because of his experiences with his father. [He said], “Doctors don’t say, ‘Just come whenever you can get here. We’ll see you.'”

Receiving the stage 4 diagnosis

My husband took me to the last hearing that I conducted as a practicing attorney, and I won. Of course, you have to include that. My husband took me to the hearing, and then we drove up to my doctor’s office.

What’s funny is I didn’t really like the medical oncologist the first time we met him. He has a daughter that’s very close to my age, and he was just very paternalistic. [It was different] going from my breast surgeon, who was like, “Let’s talk about it. All the details. Let’s make the best decision.”

He was very like, “You’re going to do X; you’re going to do Y.” I kind of bristled at that. It’s kind of like, “What, you’re going to tell me what to do?” In hindsight, he was the perfect doctor to have broken that news to us.

He brought us back into his office. He put his hand on my knee. We were talking about how breast cancer was going to be something that was going to be an experience, a season, and you would die of something else. He said, “You’re stage 4. This is going to kill you.”

That was extremely sobering. It was totally out of the blue. Totally not expecting that. I had a 5-centimeter tumor in the middle of my right femur. My breast tumor was only about 2.4 centimeters. It was bigger in my leg than it was in my breast. They were worried that my bone was going to shatter.

Processing the Diagnosis

Initial response to the diagnosis

My first thought after he said this was, “My kids aren’t going to remember me.” They had turned 2 and 4 at that point. He started giving some statistics, and he was very careful to say, “You are not a statistic. Statistics are not everything. I have patients that have been living for 10, 15 years with metastatic disease. But this is a serious situation.”

I had bone-only metastases at that point; it only spread to the bones. There was some data that was a longer life expectancy than if cancer was in your organs. He shared that with us. He was very kind, and he let us ask all the questions.

Of course, I tried to pin him down onto, “What is the timeline? I get 10 years, right?” He’s like, “Well, some people do.” It was a very good balance of hope and reality. He was going to manage me being on tamoxifen, which is typically a hormonal medication that you’re on after you finish chemotherapy when you have early-stage breast cancer. He said, “Now, we’re going to be talking about totally different medications.”

How did you process your second diagnosis?

I think partly because of my training and partly because of my personality, I tend to think about something first, and then the feelings come later. At the time, it was much more of a project management type of, “Okay, how are we going to fit all this in?” I was thinking much more about the nitty-gritty. “This was going to be the plan, but now that’s all blown out of the water.”

It was a lot of trying to assimilate and understand what’s going to happen now. I vividly remember he sent in his social worker, who was 22, right out of college, and she was trying to talk to us about how we felt about things. We were both just like, “Now is not the time. We’re overwhelmed with all of this.”

We got into the car. I told my husband, “I can’t drive. You have to drive.” My brain was just whirling, and we both cried all the way home. A lot of it was about the kids. A lot of it was that they’re going to lose their mom at such a young age. One of my first thoughts was, “I have to protect them against the crazy stepmother that my husband is going to marry, this other woman, and there’s going to be other kids.”

»MORE: Patients share how they processed a cancer diagnosis

Mental health support

Your brain goes to so many weird places when you have a trauma like that. I don’t think that my executive functioning was fully online. I think [I was] just kind of bouncing all over the place. It took about a week, I think, for things to really marinate and for us to really wrap our heads around things.

Of course, I was in surgery within a week to get titanium rods put in both femurs, and so there were a ton of appointments as well. We had a business, my law firm. We had employees. I had a roster of clients. There was a lot of, “Okay, I have to take care of all these different pieces before I can even focus on what’s going on with me.”

It was about a week or so, maybe 2 weeks after the diagnosis. I started seeing a psychiatrist because I realized very quickly that the coping mechanisms that I had developed over my 38 years of living were not up to the task of dealing with this huge diagnosis.

[I] sought out mental health treatment and got on medication pretty much right away to manage anxiety. There was depression, those dark nights of the soul, when you are just thinking about the end of your life. That’s what I obsessed over for the first couple of weeks.

Getting all those different pieces of support. My parents came up. We lived in Orlando when I was diagnosed. My parents were in Miami, so they came up. My mom was with me in the hospital, spending the night after surgeries.

Realizing how serious things were?

I didn’t fully grasp how serious things were. I did on some level, but it became so real when we were in the orthopedic surgeon’s office. He pulled up my scans. I had not looked at my scans. Now, I look at everything, but at that point, I was relying on the doctors to tell me what was going on and what was in the scans. He pulled it up, and it was a picture of my right femur.

On an X-ray, your bone is supposed to be white. That’s the color it’s supposed to be. Mine was mostly black, or it looked that way to me, because there was so much cancer. If you think about your bone being round or 3-dimensional, much of the bone was full of cancer. In that area where the tumor was concentrated, it looked like there was only really one area of the bone that was still solid.

Reacting to the X-ray

One of the nurses wouldn’t make eye contact with me through the whole appointment. She told me later that it was because, of course, I had started chemo. I was bald. I did not look healthy. She told me later that it was just really triggering for her because her sister had just been diagnosed with cancer. She made me this bracelet. It was very kind.

I did not fully connect with how serious it was really until that moment. I didn’t fully understand even some of the conversations that were going on among my doctors. One of my friends actually saw my radiation oncologist recently, and she expressed some amount of surprise that I was still alive.

I think [it was because of] the disease load. It was in every bone, and every bone was liberally sprinkled with cancer: all through my spine, it was in [my humeri], but my legs were the worst. Obviously, you need your femurs to walk and to remain upright. Those are kind of important bones. That was the focus.

I found out on a Friday about my diagnosis. The following Friday, I was in surgery to have the titanium rods put in both femurs. We decided to finish the Adriamycin and Cytoxan, save the Taxol for later, and then we scheduled my hysterectomy, too.

Processing Cancer and Finding Community

Processing the Diagnosis

When did you allow yourself to grieve?

There’s a lot of grief when it comes to any cancer diagnosis. I think that you go from being a healthy person generally. It’s a betrayal, right? Your body has betrayed you in a lot of ways. I think that really resonated with me a lot at the beginning.

I did what a lot of people tell you not to do, which is I went online. Certainly there was Google, but then through some of the ladies that I talked to that my surgeon had sent me to — and my mom because she had been through treatment as well — [I found] different support groups and other people to talk to.

[There was] one thing that was extremely traumatizing. One of the support groups I joined probably 2 or 3 weeks after I found out I was stage 4, 3 of their members died in the week that I joined. That was so sobering and overwhelming. I don’t know that I really did process things very well initially. It was not until things died down a little bit.

We transitioned my clients and a lot of my staff to the firm of some dear friends of mine. It was a good transition. They practiced very similarly to me. It was a lot to undo all of the contracts. We had actually just signed a contract to move into a new office.

Once the logistical stuff was done — because again, I think first and feel second. I focused on doing all of that. I had so much downtime. [I went] from working at a million miles an hour with my hair on fire to having all that downtime. My kids were in a Montessori school, so I had all that time during the day.

What helped with your emotions?

That is when a lot of the emotions started coming, and I found a lot of relief in writing. I have a literature undergraduate degree, so writing, journaling, and that sort of thing has always been something that has been helpful for me. I found a lot [of] release there. The psychiatrist that I saw did talk therapy, as well as the medication. That was helpful, certainly.

Connecting with other people who are going through the same thing, I think, has probably been the number one thing to alleviate some of the intensity of those feelings. The ability to say, “I’m going through X,” and there’ll be 20 people who respond, “I’m going through the exact same thing.”

That was such a weirdly comforting thing that we’re all going through something so awful at the same time, but it was. It was really helpful outside of the place where all the people were dying. I got out of that group because that was too much at the beginning for me.

I now moderate a Facebook group that is specifically geared toward the newly diagnosed. We take the people in the first 2 years of MBC diagnosis and really mentor and model for them. We’re kind of onboarding them into the MBC community, and then we get them into other groups and let them graduate. [We do this] because of those initial experiences that a lot of us have had, because death is such a constant in the MBC community.

Coping with cancer and loss

Finding the coping skills and finding the ability to handle that, I’m still not good at it. It’s been 5 years. I’m still not good at it, but I have more coping skills now. A lot of it has to do with these key people that have the same disease that we can really just talk frankly about what’s going on. Support groups where that’s facilitated [have] helped, in addition to the direct connection.

I started CaringBridge sites pretty early on just to keep everybody informed. Things were changing every day, and that made a lot of sense to keep everybody informed that way. I think writing and talking with other people have really been the best things.

All of them understand. It seems like the intensity happens at night. The amount of times that I’ve texted friends of mine in the MBC community — I’m always thankful for people in different time zones because it’s not the middle of the night for them.

[I’m thankful for] being able to talk things through and just really say that this what I’m feeling at this moment instead of stuffing it. I was a very good stuffer before this. Again, coping mechanisms that do not work for a terminal diagnosis. Stuffing is not good. That’s not a good thing.

Parenting while dealing with cancer

Being open with your children

Our parenting style has always been to be as open and honest as possible with our kids on the correct developmental level. One of the things has just been to talk to them, to make sure that they’re equipped with information generally. We’ve done a lot around helping them to name their emotions.

We have a whole lot of books that we read. “The Invisible String” is a big favorite, talking just about how whether you’re at school or somebody is not around anymore, that love connects you to the person that you are connected to.

I think that one of the things that I read when I was a new mom was just this concept of how we’re always the ones behind the camera. We’re always taking the pictures, so we’re not often in the pictures. That’s for a lot of different reasons.

I have prioritized having regular professional photoshoots. We do one for Christmas cards every year. Then I’ve told my husband, “I don’t want all the stuff for Mother’s Day. I just want a photoshoot so that we have that record of them, of me being in their life.”

»MORE: Parents describe how they handled cancer with their kids

Making memories with your children

Both of them are very active children. They’re both boys. I was always very active with them prior to my diagnosis. That was a huge change because I was on crutches and then a walker and wheelchair, especially after my leg surgery.

Energy is something that is in short supply when you’re in treatment and radiation. It makes you so tired as well.. I had radiation to my legs and to my back. [I had] to adjust to not being active with them, but finding other times of connection with them.

All the parenting stuff talks about how you’re not going to be in your children’s memories if you’re not in their lives today. Because I’ve had the ability to have more time with them, because I’m not working and running around and having a million to-do’s, I’ve been able to be a lot more intentional in spending individual time with them, putting the electronics away.

I do a date with each of them once a week, where we go out. It’s usually for ice cream because of course they want ice cream, although my older son is now quite obsessed with the French bakery and croissants and lava cakes and all of that.

Every week, and now we’ve done this for years, I’ve taken them out and just had an individual conversation with them about whatever it is that comes to their mind. I’m just trying to be very intentional about being in the moment with them, about listening to them, trying to consider very carefully the lessons that I want to pass on to them. I also have memory boxes for them.

Leaving letters for the future

Our niece got married. Her husband was there dancing with his mom, and I about lost it. Of course, I immediately thought, “I’m not going to be able to do that.” The likelihood of me being here, although we hope so, when they get married is low. I’m not going to be able to have that dance with my son at his wedding, either of them.

What I have tried to do in terms of channeling that emotion, channeling that energy, is I sit down and write them a letter to open on their wedding day. I have a box full of letters for different times. I don’t even know where I came across it, but I came across a list of all the times that you want to hear from your mom.

You come back home after your first binge drinking or wake up with your first hangover, break up with your girlfriend for the first time, buy your first car — all those milestones and moments that it is unlikely that I’ll be here for. I’m trying to have a card for them to open with my handwriting, with my reassurances and those kinds of things.

Saying the important things while you can

I have realized over the last 5 years — not just with my kids, but with everybody — that you have to say the things that are important. You have to say that you love people. You have to say that you care for them. You have to verbalize those things because we have no idea what’s going to happen tomorrow.

For so many of my friends in the MBC community, once the cancer gets out of control, it’s a very short time period between finding out there are no more treatments and death. We typically don’t get a lot of time in hospice. I have friends in the last month that passed away, and they literally went out of the hospital into home hospice and died the next day. That is the trajectory of this disease.

This is my legal training. I try to look at the worst possible thing that could happen, plan for that, and then everything else is taken care of. We tried to look at those kinds of things unflinchingly, but saying the things that you need to get off of your heart, I think, is one of the big things that we’ve tried to do with the kids.

I’ve just tried to do with relationships in general because you don’t know what’s going to happen. I think those of us dealing with a serious illness, we have a little bit more of a sense of that, just because we have a serious diagnosis. Somebody can die at any point.

Preparing financially

We also redid our trust. I am thankful that as a young professional, I got a good private disability policy. I also signed up for probably more life insurance than I really needed to because I practiced a little bit in personal injuries, so people who get into car accidents.

Ever since then, even though I despise insurance companies, I have every type of insurance you can think of because I’ve seen what happens when you don’t have the coverage. It’s a domino effect of losing things — your house, your car, your job, etc. — when something serious happens.

Thankfully, we had planned for that. We redid the trust that we have set up for the boys. One, I was trying to protect the money from the evil stepmother. See, it’s still a theme. It’s still something I think about. Also, just thinking I’m not going to be around to help them figure out what to do with money with these kinds of decisions.

My husband’s a banker. He’s obviously very well equipped with that. We have a few more restrictions on what they’re going to be able to do with that money, like not being able to get the principal until they’re at least 30. I just tried to be very intentional about those things, about my legacy, and about what I’m going to leave behind.

Living with Cancer

Jolting changes to life

I think the average age of breast cancer diagnoses is still 60. It’s still mostly people who are either retired or heading in that direction. But when you’re diagnosed in the middle of your career, the middle of what’s supposed to be your productive years, it’s jolting on so many different levels.

I talked about all that time that I had on my hands after things got wrapped up with the firm. When you have a career versus just a job — maybe it’s not as much for women as it is for men — I think a lot of our identity becomes wrapped up in what we do for a living.

I love the spoon theory, where we wake up with less energy or less spoons than a healthy person. We can’t just drink a cup of coffee and get more energy. Once the energy is gone, it is gone.

For me, anyway, the idea of advocacy has always been something that permeated my entire life. I think I identified with helping people and advocating for people. That sort of thing is a big part of who I am. When you are deprived of that purpose or the thing that gave your life purpose, then you start looking around and saying, “What am I supposed to do now?”

For me, it was a lot of boredom. You can only read so many books and watch so many videos or movies on Netflix. I very quickly found that sense of restlessness. Certainly, I also had a lot of physical impairments, having to really work at getting mobile and being able to walk better. At the beginning, there are cognitive deficits that come about because of chemo.

Managing self-expectations with low energy

A lot of what I struggled to figure out was, okay, I have these expectations of myself. I have this knowledge of myself as a healthy person. What is this now? What can I do now? That was where I found my way into patient advocacy. I’m not just advocating for myself, but working with nonprofits to advocate for others in the community.

[I] very quickly found that there is a hole when it comes to the people getting good legal advice. I had great legal advice because all my friends are attorneys, and all I had to do was call up a friend of mine and ask a legal question. Most people don’t have that access.

[I] started to delve into the ability to use my experience and use the things that I had already done to do that, but then still struggling with this adjustment of, “I can’t think of the word.” I love the spoon theory, where we wake up with less energy or less spoons than a healthy person. We can’t just drink a cup of coffee and get more energy. Once the energy is gone, it is gone. I would literally sit there and fall asleep sitting talking to somebody.

That’s a huge adjustment from being very high functioning. I think that those of us who go from a 90-miles-an-hour career to a cancer diagnosis, that’s a much bigger change than those people who are either already retired or kind of winding down in terms of the things that they’re doing. Plus, I have young kids, versus people who have adult children.

Being diagnosed with cancer at a young age

I think the younger breast cancer experience is very different. I think that a lot of hospital systems and survivorship clinics don’t often remember that it is very different for us. That has been a bone of contention between myself and every single one of my doctors about how the general rule just doesn’t apply to me. You can’t just make an appointment for me during school pickup, because DCF gets a little upset if I leave my children at school. A lot of that has been something that I’ve had to educate people about.

Social media has allowed me to connect with other younger women with breast cancer, because our experience is so different. We’re a minority still, but the under-40 population is the only segment of the population where diagnoses of breast cancer are growing and continuing to grow. In all other segments of age ranges, it’s declining. I don’t know why that is.

In some ways, it’s kind of a double-edged sword, but it’s kind of good that more of us are educating our doctors because I think they will be more sensitive to our experiences. It’s obviously a terrible thing to be diagnosed at a young age with something so serious.

Complete overhaul of life

Because mine was a de novo diagnosis, I was not given the opportunity to go through treatment, have some years of no evidence of disease — and you notice that I’m not saying cured because there is no cure for cancer — and then have a stage 4 diagnosis.

I find that the people who go through that trajectory in terms of their disease just have a very different experience. It was just a complete overhaul of our entire lives from the very beginning. Not that I think that that’s necessarily a bad thing overall.

I think we can learn a lot from people who have serious diagnoses because we have a whole different perspective on the things that matter. How often do we get so focused on things that don’t matter in our lives because we’re just caught up in whatever it is?

Community

The importance of finding support and community

First, let me talk about finding people. Most cancer centers and doctor’s offices have either a support group that’s managed by a social worker or peer support groups. COVID changed a lot of that in terms of in-person groups, although I still think that meeting with people in person is so very important.

Social media has become a really good way of connecting to people that have a similar disease experience. Even the people who don’t have children, I find that sometimes I can’t even connect with them as much. Yes, we can connect on the disease level or on health care experiences and insurance. But when it comes to the lived experience, the people who have young kids are probably the people that I end up connecting to the most.

I don’t think I’ve ever met somebody who has been diagnosed with cancer who doesn’t have a story of healthy people ghosting us. What I mean is when you have somebody who has been in your life in one way or another, you have a serious diagnosis, and they do not engage in any way. They completely leave.

Over the last 5 years, that’s happened to me. It’s happened to me with family. There were people who just couldn’t handle things. I have mostly gotten to the point of understanding and remembering and reminding myself that this is not about me. It’s about them. There are those people who don’t have the capacity to enter into the suffering of somebody else.

I have found over the last 5 years that when we do enter in, when we sit with people, there is this whole concept of holding space and just being with people. [We’re] not trying to fix anything, not trying to change anything; we’re just connecting and being with someone else in a space, whether it’s virtually or in person.

The connections that I have made in the MBC community are the deepest that I’ve ever had in my entire life, and I mean people even that I’ve known for decades, sometimes even more than my husband. It’s because we get each other’s suffering on such a deep level.

I hear from various people that people in other cancer communities are often jealous of how in the breast cancer community we do this community thing pretty well. Yes, there are still disagreements and whatever, but we do this connection thing in a way that I’ve never experienced in any other segment of my life.

Making deep connections in the MBC community

Acute vs. chronic trauma

I have continued to be connected to people who don’t have cancer, but the vast majority of the people who have stuck around are the people who’ve been through trauma themselves. We have a great group of friends from Miami, where we lived for a bit, where each of them has a child with a very serious diagnosis, whether it’s autism or strokes or other syndromes.

They get on a different level what it’s like to be in a trauma. [It’s not like] you get a diagnosis, you go through treatment, and maybe you’ve got some side effects that last. I don’t want to discount the fact that there are side effects that last after chemo. The people who are in the trauma for life, you’re in that trauma over and over and over again for the rest of your life. There’s a sense of community, and there’s a sense of connection. There’s a sense of going deep really fast that happens in no other area.

You remember the emotions. You remember the connections with these people or with people that have made an impact on you.

The price of that is that when the people you have gotten that close to and you have connected that much to, when they die because they have a terminal diagnosis like mine, a piece of your heart goes with them. There have been several times where I’ve gotten very close to somebody, and they died. I said, “Well, forget this advocacy stuff. I don’t want to be connected to it.”

But I keep coming back because of the genuine connection. I read a meme, something about how amazing it is when you’ve got somebody who has gone through the fire, and they’re handing buckets of water to the people entering into that same fire. That is a good visual for me of what we do in the MBC community. Sometimes well, sometimes not so well. There’s a connection there that’s just like no other connection.

Disenfranchised grief

Some of these people I’ve never even met in person, which is a weird thing and does lead to some of the concept of disenfranchised grief, where it’s not normal or mainstream grief. You talk a lot about miscarriages or the death of a pet or somebody you’ve never met online that you’re grieving for. There aren’t great grief rituals in those contexts. You can’t necessarily go to a funeral and have the expected support and things that would happen [if] you lost your parent.

My husband just lost his father, so we just went through this. It’s that sense of being disconnected at that last piece so that you don’t get a chance to do the grief rituals. A lot of families do their funeral. It’s not necessarily public, where they invite people from the community to attend those things. It’s weird, and it’s a strange, great space to be in. That’s something that we talk a lot about, just developing grief rituals that help us.

There are 3 deaths. One is when your physical body ceases to function, the second is when your physical body is buried, and the third death is when people stop saying your name.

One of mine — I’ll grab my bowl over here — is for the people who I’ve gotten very close with, I have a rock with their names on them. I keep it in my space. That’s part of how I remember them. I sit down, and I decorate a rock after they’ve passed.

I’m not very artistic, so I can do little flowers. That’s pretty much the extent of some of my creativity. Some of them just have the name and a heart on them.

We’ve done a fair amount of grief circles, where we get together and talk about and memorialize that person. I keep close to me the things that people have given me. I have various little notes and a stack of cards that I’ve gotten from various people who have since passed away.

Every now and again, especially on the anniversary of their deaths, I go back through that and just remember the things that were good about that relationship, remember the things that I’ve gotten from that, and remember that connection and that love. Because that’s what keeps bringing me back to the community.

What do you feel when you are holding the rocks with their names?

I remember them. I remember the times that we had together. There’s that saying that people don’t remember what you said, but they remember how you made them feel. You remember the emotions. You remember the connections with these people or with people that have made an impact on you.

One of the things that we talk about our kids quite a bit about is when they’ve had different experiences with different people — especially the ones that we’ve lost, like my husband’s father — we talk about that person. I have learned over time to not stuff (because that was one of my coping mechanisms before cancer), but talk about the people.

On Twitter and other places on social media, we talk about these people a lot. I still tag people who have passed in some of my posts when we’re talking about various things that remind us of that person. In our support groups, we talk about these people.

I don’t remember what tradition it’s in, but I read somewhere that there are 3 deaths. One is when your physical body ceases to function, the second is when your physical body is buried, and the third death is when people stop saying your name. I think one of the things that we do in our community for each other is that we say each other’s names.

We talk about the impact that those people have made, especially the ones who have been advocates and who have been very public in what they’ve accomplished. We’re just honoring their accomplishments and honoring what they were able to do with the time that they had.

It all helps. None of it’s easy. None of it is simple. I think everybody has different things that help them process.

Remembering as a way to heal

There’s a podcast, Our MBC Life, that is specifically for the MBC community and is created by the MBC community. It’s through SHARE Cancer Support. Every year, we have a memorial episode, and everybody calls in to say the names of the people that we’ve lost in the last year.

It’s a very difficult, but a very healing time to really focus on the positive impact and the things that people did that touched us. Those are the things that I want people to remember about me.

Having that as part of the routine is helpful, and I think it’s helpful to begin talking about that with my kids. They dealt with their grandfather’s death, I think, better than they would have if we had not been doing a lot of this, talking about what happens when people die. “Yes, that’s Grandpa’s physical body, but that’s not Grandpa anymore. His spirit, the thing that makes him him is not here anymore.”

I’m hopeful that doing some of that and having that be very natural, matter of fact — this is the part of life, birth, death, and all of that — will help my kids make that transition after my passing as well. I’m trying to be very intentional even about prepping them for that.

Undergoing Treatment

Different Treatment Options

What were your side effects from treatment, and how did you manage them?

The way I’ve learned to look at treatment is that the more information we know, the better the doctors can prescribe the right treatment. One of the challenges that we had in the first about 4 and a half years of my treatment was because I only had bone mets. It’s very difficult to get information about the metastases.

Stage 4 is when the cancer has left the original site and gone somewhere else. For me, I think about 60% of the cancer went from my breast to my bones. When you try to get a biopsy of a met that’s in a bone, you have to decalcify it before you can actually look at it under the microscope. That process of decalcification often destroys the cancer. We had not been able to see how the cancer was mutating.

In a metastatic cancer diagnosis, we’re basically on treatment until the cancer mutates around the treatment. Knowing what treatment to be able to target something in the cancer, to stop it and to deprive it of fuel, is why I had the oophorectomy to check out my ovaries, because that’s the main source of estrogen.

For those of us with estrogen-positive breast cancer, that’s typically the strongest receptor, so that’s the main thing you want to take away. The cancer in my body is now resistant to a lot of the hormonal medication because it has learned, because cancer is always learning and mutating around.

CDK4/6 inhibitors

We’re testing what we can through liquid biopsies. In January, the cancer spread to my liver, so for the first time we were able to get a met and look at it and see how it had so fundamentally changed. Unfortunately, cancer treatment is a lot about chasing. Not chasing but staying ahead of the cancer, because we don’t want to chase the cancer. Once we’re chasing it, it’s gotten out of control. We want to control it as much as possible.

The good thing for me was that going through Adriamycin, kind of the big chemo, meant that I could stay on targeted therapy for 4 and a half years. My first line of treatment in 2017 was Ibrance, which was approved by the FDA in 2015. I was able to be on a medication that had just recently been approved by the FDA, which is huge.

That line or that class of drugs, the CDK4/6 inhibitors, has really changed the landscape of breast cancer. Starting in 2015 with Ibrance, and then there’s now a fourth one that’s being added to that class. People are living a whole lot longer with far less side effects. My first line of treatment after I finished chemo was Ibrance and letrozole, and I was able to be on that for 2 years.

There were very low side effects. Most targeted therapy affects the bone marrow, so we had to watch for low white blood cells, or neutropenia. I was always immunocompromised and having to be careful. The main side effects were the blood counts and some fatigue.

Switching to Piqray

The value, I think, of having gone through that misdiagnosis was that I got the big guns, Adriamycin, and then I was able to get 2 years of stability on Ibrance. Then in August of 2019, the cancer mutated, but it was still in my bone. We switched to a different targeted therapy, Piqray.

Ibrance works by disrupting the CDK4/6 pathway, and that’s how cancer grows or can grow with the pathway that cancer often uses to grow. Piqray was targeting a very specific mutation called PIK3CA, which is actually present in about 80% of people with breast cancer. It’s pretty significant.

In 2019, it was approved by the FDA in May, and I started it in August. I try to have those dates because that is research benefiting people directly. Now, it typically takes about 10 years for medication [to go] from concept to actually get in the clinic, although there are some new ways that drugs can be fast-tracked, and things like that that have helped. It takes a long time for medication to get from concept to actually be given to the patient.

Research and fundraising

It’s so significant. Research advocacy has been something that I’ve gotten really involved in. I go to all the big conferences. I think my medical oncologist was a little surprised, and I was like, “Hi, I’m here at the conference for all the doctors.”

It gives me a little bit of a sense of control. You’re so vulnerable, and you are so out of control when you are in the health care system, that having even a little bit helps me. It helps me cope with the uncertainty by learning as much as I possibly can about the drugs that are in the pipeline, about what trends are we seeing (you see that in the big conferences), and where the drug companies are reporting about their data.

One thing that has been a huge part of that is participating in the GRASP poster sessions. GRASP stands for Guiding Scientists and Advocates to Scientific Partnerships. They pick the big posters or the significant posters. I’m talking [about] an actual poster, a gigantic thing that’s full of words and really, really confusing graphs.

We have these small groups, and it’s all on Zoom. After each of the big conferences, we have these small groups, where we talk to the poster author, we have a clinician there, and then we have patient advocates. We talk about what is happening in the science.

Why is this thing important? When I went to the big San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium in December of 2018, that’s when [everybody was all excited about] Piqray, which I eventually was able to be on.

The future of treatment

At the most recent conference for the American Society of Clinical Oncologists, there was a standing ovation at the news about a medication that just got approved by the FDA recently for treatment of HER2-low, and that’s [the] first one. In the last 5 years, I have seen these drugs that come [that are] the first in their class.

They’re the first way of identifying and of attacking certain pathways in your body. It’s immunotherapy, where we’re teaching the body how to attack the cancer, which I think is the future. I think that’s the future of precision medicine, teaching our body how to deal with it versus having to stay on this treadmill of medications.

Being in the room and hearing about these things and just hearing the excitement in terms of that. San Antonio was like 40,000 people that come to this from all over the world. These people have made breast cancer their life, their everything. They are in the lab 24/7 trying to figure these things out.

One of the really key things that has given me a lot of hope is that there are all these really, really, really smart people who are giving their lives to figure this out, for one reason or another. For most of them, it’s not a profession. It is their life. Seeing that dedication and seeing that energy put towards finding medications…

Unfortunately, I think breast cancer is too complicated to find a cure, but we are getting so much better at treating different subtypes. People are living so much longer. Like I said, the CDK4/6 inhibitors really changed the landscape. That’s the first line of treatment that everybody gets now, a CDK4/6 inhibitor almost exclusively.

Patient advocacy

Over the last five years, I have seen how patient advocates can fuel and push research during the time that I’ve been diagnosed. It used to be that if you had brain meds, you couldn’t participate in clinical trials at all. Now, most clinical trials will accept you so long as the brain meds are stable.

That has been something that has been fueled and pushed by the doctors, but also by patients speaking up and saying, “Hey, wait a minute, you’re excluding me just because of this one thing. Otherwise, I fit perfectly in your trial.”

I think as a lawyer, I get a lot more of the limitations of our system. There are all these regulations. The drug companies have to fit in this box, which is there for a reason. We don’t want to repeat all of the horrific things that happened in Tuskegee and with all of the things that a lot of doctors did for a long time, especially in minority communities.

The importance of clinical trials

It’s still only about 3 to 5% of us that participate in trials. One area where I try to educate people a lot is the only way that we will have more medication is if people participate in trials. Trials are not for the end. It’s not for when there’s nothing else. I’ve already participated in 4 trials, and none of them have been about medication.

It’s all been about improving algorithms to look at liquid biopsies, where we can see things in the blood without having to look at a soft tissue met. Actually, the very first genomic testing I had, which was looking at the mutations that the cancer had acquired, was done through a study.

It’s so important that we participate in this research for the scientists to be able to discover and understand things. The fact that we enroll so few minority populations in these trials means that they’re only testing stuff on middle-aged white women. I am a middle-aged white woman, so I’m happy that they’re testing things on something that most likely would work for me.

But then how do we know if it is going to work for somebody who’s from the islands or somebody who’s from Africa or somebody who’s from an Asian country? It’s so hard for scientists to be able to tease out all the different specifics about our bodies without having people to test it on.

What are the differences between genetic and genomic testing?

Genetic testing is the stuff that changes in your DNA, so what you get from your parents. Obviously, you get half of your copy from mom, half the copy from dad. Sometimes, if there are DNA mutations on both sides, that creates something entirely different, and they learn so much all the time.

I do want to say one thing about genetic testing. 23andMe or Color Testing or Ancestry.com is not genetic testing. That’s information that’s available to the public. The genetic testing I’m talking about is through a lab that is FDA approved. You’re not going to get the same information from something that’s like, “Hey, do you have more susceptibility for cholesterol?” That’s different from the genetic mutations that I’m talking about.

Like I said, now the panel is 93 genes that they’re looking at that have to do with breast cancer. I’m just talking about breast cancer. There are so many different genes that are associated with all kinds of other things. I don’t have mutations anywhere other than in this ATM gene. That has to do with breast cancer, ovarian cancer, prostate cancer and colorectal cancer. That’s the makeup of your DNA. That doesn’t change. That’s static.

Then the cancer, as it mutates, acquires somatic mutations. That just means in the body. Genomic testing or tissue, with the cancer that they’re looking at under the microscope, gives you the genomic data, and that typically (hopefully) perfectly gives you targets. I talked about the PIK3CA mutation. That’s a target, where we have a medication that targets that.

Using genomic testing to plan for progression

One of the things that came up on my recent genomic testing is that the cancer has acquired the PD-L1 somatic mutation, which is an indication of sensitivity to immunotherapy. This is the knowledge that the doctors have [to use] to then build out options. I always insist that my doctors give me plan A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, all the way down the alphabet, because I want to know all the different things.

When there’s the progression and you have to change the medication, if you haven’t already selected or pre-selected some options, it’s chaos. You’re overwhelmed, and you’re having to make really big decisions. I like to make sure that I have the list ready. If there’s a big progression, we’re going to go this way. If there’s a more minor progression, we’re going to go that way.

That genomic testing can give doctors the building blocks to be able to put together a treatment plan. That’s the science part. I’ve also been so blessed to be with doctors who have been doing this for so long that their clinical knowledge, their gut, because they’ve just absorbed all this data for all these years — and we as individuals are not statistics — that they can look at us and draw on that experience.

That’s what I call the art of practicing medicine. You have to have both. You have to have the scientific data, the scientific research, the peer-reviewed studies, and the understanding of what kind of side effects you might be experiencing when you’re going into something, But then you also have these doctors who have this more intuitive feel.

Experimenting with treatment

One of the things that’s happened since I’ve changed teams, since I moved from Miami to Orlando, is a lot of my new doctors are looking at my treatment plans and saying, “Oh, you did things very differently.” And we did. My doctor and I experimented.

I talked a little bit before about Piqray. I had a PET scan after I had been on Piqray for about 6 months. All the cancer was becoming more metabolically active, meaning I was about to have a progression. We added a third drug. I was on Piqray and on Faslodex, which is the hormone suppressor, and then we added Kisqali, which is another CDK4/6 inhibitor similar to Ibrance.

There was a study on that particular combination, or an arm of a study on that particular combination, and no one was able to stay on that combination. I was on that combination for 2 and a half years. You don’t know how your body is going to respond until you try. Some people have no side effects on particular medication.

Piqray is known to cause hyperglycemia, so I was on glucose drugs for the entire time that I was on Piqray. Not a super easy drug, but I got 2 and a half years off of that particular rather aggressive combination. I think one thing that I’ve done in my treatment is that I have not been afraid to try something that may or may not work.

How Treatment Affects Life

Why is Piqray a hard drug to be on, and how did you deal with that?

Hyperglycemia — people mostly associate that with diabetes — can cause a whole lot of things in your body. There’s a rash that Piqray often causes as well. You have an allergic response to it, but hyperglycemia is probably the biggest thing. Pricking my finger every day and having to be on medication to manage the hyperglycemia.

That is probably the biggest challenge that most people face on Piqray, especially just because hyperglycemia is one of those things that affects your whole body. It affects everything. Managing the hyperglycemia can actually be a really, really big lift.

Oncologists go to school for oncology. They don’t go to school to manage hyperglycemia. The endocrinologists know how to treat diabetes, but it’s not diabetes. It’s medication-induced hyperglycemia. People were finding themselves in this very big gray area.

I’m extremely proud to say that I’ve been working with Novartis, who is the drug company that produces Piqray. Anyway, we have a poster coming out at the ASCO session that’s coming up, and it’s all about teaching the doctors how to manage the hyperglycemia. Literally, you have a patient that comes in with this, do this. If a patient comes in with that, do this. [It has] preferred drugs and dosages and everything like that.

This has been a huge labor of love in a lot of ways. I’m the only patient advocate on the panel. I think there were 12 or 15 doctors, endocrinologists and a medical oncologist. We had a pharmacist. That’s probably one of the most amazing things I’ve ever done, because I brought the patient experience to the table.

Plus, I moderate a Facebook group for people on Piqray, and we have hundreds of people in the group. I was able to do some polling of the people in the group to bring some real-time data to these discussions. This is where patients can help educate, because all the doctors on this panel are all at major academic centers. The vast majority of people being treated for cancer are in rural settings, not a major academic center.

Some of the doctors that treat you in the community are not maybe a breast specialist. You may see an endocrinologist who’s not an oncology endocrinologist or [doesn’t have] some of that specific training or experience.

The doctors didn’t know what to do, and that was such a huge issue for so many patients that Novartis put their money where their mouth is and invested in coming up with these guidelines [from] discussion and consensus among all the different specialties.

Yes, I was very proud to participate in that, and part of it was because I was harassing Novartis about all the things that people were talking about in the group and referring them to the patient advocacy program. Their doctors were trying to figure things out. I think they finally said, “I think we need to give this person a job.”

Treatment affecting quality of life

Grade 3 diarrhea means you’re in the bathroom like 10 times a day. If you’re only doing that for a couple of days, okay. You deal with it, maybe take some medication, whatever. Then the rest of the time between treatments is not so bad.

The difference with these oral meds is that that’s the side effect that you have every day, 24/7, for all the time that you’re on the drug. I have seen a shift in the last 5 years of researchers really beginning to understand that. You start looking at it really closely when it’s about grade 3. Grade 5 is death, just to put it in perspective.

They’re paying a lot more attention to that and understanding that with these oral meds, you can’t live if you’re in the bathroom 10 times a day. We talk to people about literally not being able to make it to the bathroom. As an adult, actually having an accident is not something that is okay.

We had several advocates talk about, “I think I need to wear a diaper to go to the conference because I don’t know if I’m going be able to get to the bathroom in time.” That’s the kind of quality of life stuff that I am seeing be much more focused on, thank God. Not that they didn’t want to, but I think that they needed the push, and I think they needed incentives. I’m also seeing much more of the patient voice being included in these trials.

Designing trials with patient input

The piece that I think needs to change is getting the patient advocates involved at the time of the design of the trial. So many times the trials are designed in such a way, whether it’s transportation or parking or having to be at the doctor 3 times a week. There are things that they design that make sense to them from a gathering data perspective. It’s just not livable.

This idea is of having trials where you don’t have to go to one place or don’t have to go to the major academic center. Maybe there’s more places, or you can get blood work yourself and bring it. COVID has helped this, too.

They’re becoming much more aware. There are things we can relax in terms of the structure that are not meaningful overall, but it means everything to the patient. That’s huge, getting the patients in at the beginning.