The Latest Treatment Options for Relapsed/Refractory Follicular Lymphoma

Edited by: Katrina Villareal

Discover the latest in treatment options for relapsed/refractory follicular lymphoma from leading experts to help you or your loved one navigate this journey with confidence and hope. Dr. Joshua Brody from The Mount Sinai Hospital and Dr. Celeste Bello from the Moffitt Cancer Center discuss bispecific antibodies and CAR T-cell therapy, including their benefits and side effects.

Understand the role of watchful waiting and active surveillance. Gain valuable advice from lymphoma specialists on navigating treatment options and clinical trials. Discover the importance of support groups and resources for patients.

Thank you to Blood Cancer United for their continued partnership.

- Introduction

- What is Follicular Lymphoma?

- Terminology: Watchful Waiting vs. Active Surveillance

- Standard Treatment for the First Two Lines of Therapy

- What are Bispecific Antibodies?

- Cure vs. Longer Periods of Survival

- Clinical Trials in Follicular Lymphoma

- Recommended Online Resources

- The LLS Clinical Trial Support Center

- The Right Time to Seek Lymphoma Specialists

- Final Takeaways

- Conclusion

Introduction

Stephanie Chuang, The Patient Story Founder

Stephanie Chuang: I’m the founder of The Patient Story and a blood cancer survivor myself. I went through hundreds of hours of chemotherapy for my diffuse large B-cell lymphoma diagnosis. During that time, I realized how lonely it was and how hard it could be to get good information, and that was the genesis of The Patient Story.

Our goal is to help patients and care partners navigate life after a diagnosis and what it means in human terms. We do this primarily through in-depth patient stories and educational programs. This is especially important in spaces like follicular lymphoma. Patients and loved ones are being told by doctors that it’s highly treatable but not curable, so it’s great to know the latest therapy options and clinical research. We stand behind this message of self-advocacy, especially after diagnosis.

The Patient Story retains full editorial control of all content.

We’re bringing this to you in collaboration with Blood Cancer United, which has raised and invested over $1.5 billion in blood cancer research and provides free educational resources and support. Their information specialists provide one-on-one support on questions from treatment to social and financial challenges.

While we hope that you will walk away with more knowledge, we want to stress that this is not a substitute for your medical advice.

Our discussion focuses on the latest treatment options for relapsed/refractory follicular lymphoma. My co-moderator Dylan Lepak, another non-Hodgkin lymphoma survivor who became a patient advocate, will help lead the discussion.

Dylan Lepak, Patient Advocate

Dylan Lepak: I’m a diffuse large B-cell lymphoma survivor like Stephanie. I was diagnosed in 2021. I went to the hospital with stomach pain and came out with a horrible diagnosis, but luckily, I had a very standard treatment approach. I went through six cycles of R-CHOP and since then, I’ve been good. Since that time, I’ve done a ton of different charity work and moderated online discussion boards.

Dr. Celeste Bello, Hematologist-Oncologist

Dylan: Dr. Celeste Bello is a hematologist-oncologist and senior member of the Malignant Hematology Program at the Moffitt Cancer Center. She has a special expertise in Hodgkin’s lymphoma and sits on the board of the NCCN Guidelines for Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

Dr. Bello, when you first see a patient with lymphoma, what message do you want them to take away after that first meeting?

Dr. Celeste Bello: I try to convey to them that they can relax and take a deep breath. In most cases, we can manage this quite well. Most of the meeting is trying to get everybody’s anxiety down a bit.

Dr. Josh Brody, Hematologist-Oncologist

Stephanie: Another amazing doctor and leader in this space is Dr. Josh Brody, a hematologist-oncologist, director of the Lymphoma Immunotherapy Program at Tisch Cancer Institute at Mount Sinai in New York, and faculty member of the Icahn Genomics Institute. Since 2011, he has developed The Brody Lab, a translational cancer immunotherapy lab that investigates the development of novel therapies, particularly for lymphomas, and specializes in how to use immunotherapy against treatment-resistant lymphoma.

Dr. Brody, I know that you’re very invested in patients beyond the clinic. When you see patients and family members in your office, what do you hope they walk away with from that first meeting?

Dr. Josh Brody: Aggressive lymphomas are a sprint and we need to get things going right away, but follicular lymphoma is a marathon. If you see someone starting a marathon by sprinting, they’re not doing it correctly. We don’t want to overwhelm people with information the first time we meet them. We give them the big picture that hopefully this is going to go very well.

There are a lot of great medicines for front-line therapy and second-line therapy. Some patients might need Plan C, Plan D, and Plan E, so how you develop Plan A and Plan B might impact those. Even though there’s no emergency for the vast majority of follicular lymphoma patients, Plan A and Plan B might affect Plan C, so you want to plan out the marathon thoughtfully and as best you can.

We have to be flexible because we’re going to have to change the plan depending on how things go. There are unique options available at some places that may not be available to others. We might want to do the smartest plan A so that we don’t burn bridges down the road.

What is Follicular Lymphoma?

Stephanie: Dr. Bello, could you summarize the nature of follicular lymphoma?

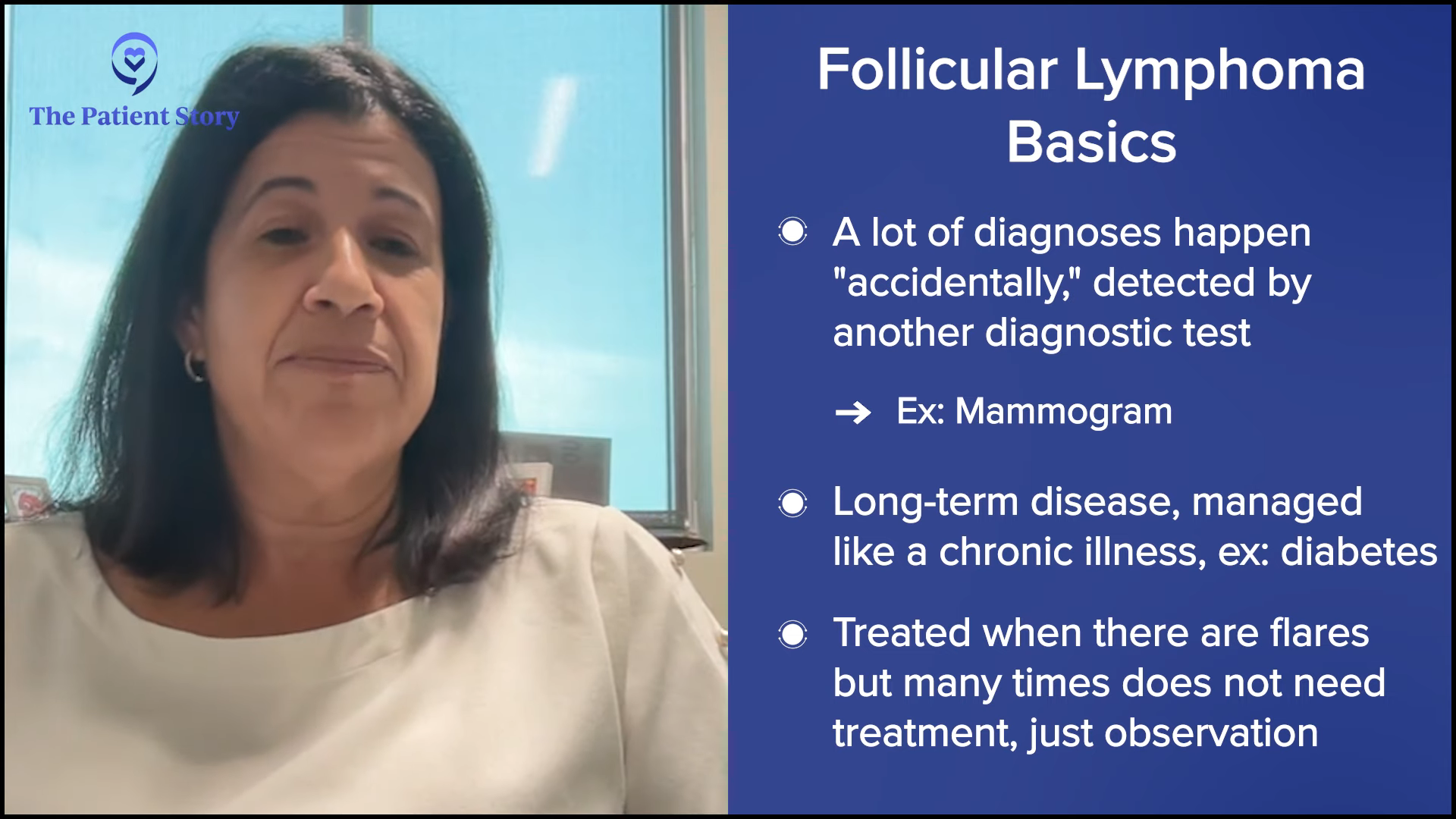

Dr. Bello: Follicular lymphoma is an interesting disease that’s broken down into different subtypes. We have low-grade indolent ones, which are slow-growing, and one subtype that’s a little more aggressive than the others. Most of the time, when we’re talking about follicular lymphoma, we’re talking about the low-grade, slow-growing one.

A lot of times, they’re picked up by accident on another diagnostic test, like a mammogram, which is a common one I see. Somebody had a screening mammogram and there’s no evidence of breast cancer, but there’s an enlarged lymph node in the underarm or axillary area.

Some can behave aggressively, so we have to keep an eye on these people and treat them differently, but as a whole, it’s a long-term disease that’s managed like a chronic illness. We try to keep it under control and if there’s a flare, we can manage that in most cases. It’s a cancer of lymphocytes, but one that sometimes doesn’t even need treatment.

Most Common Symptoms of Follicular Lymphoma

Dylan: Dr. Brody, if patients do have symptoms, what symptoms do you usually see with follicular lymphoma?

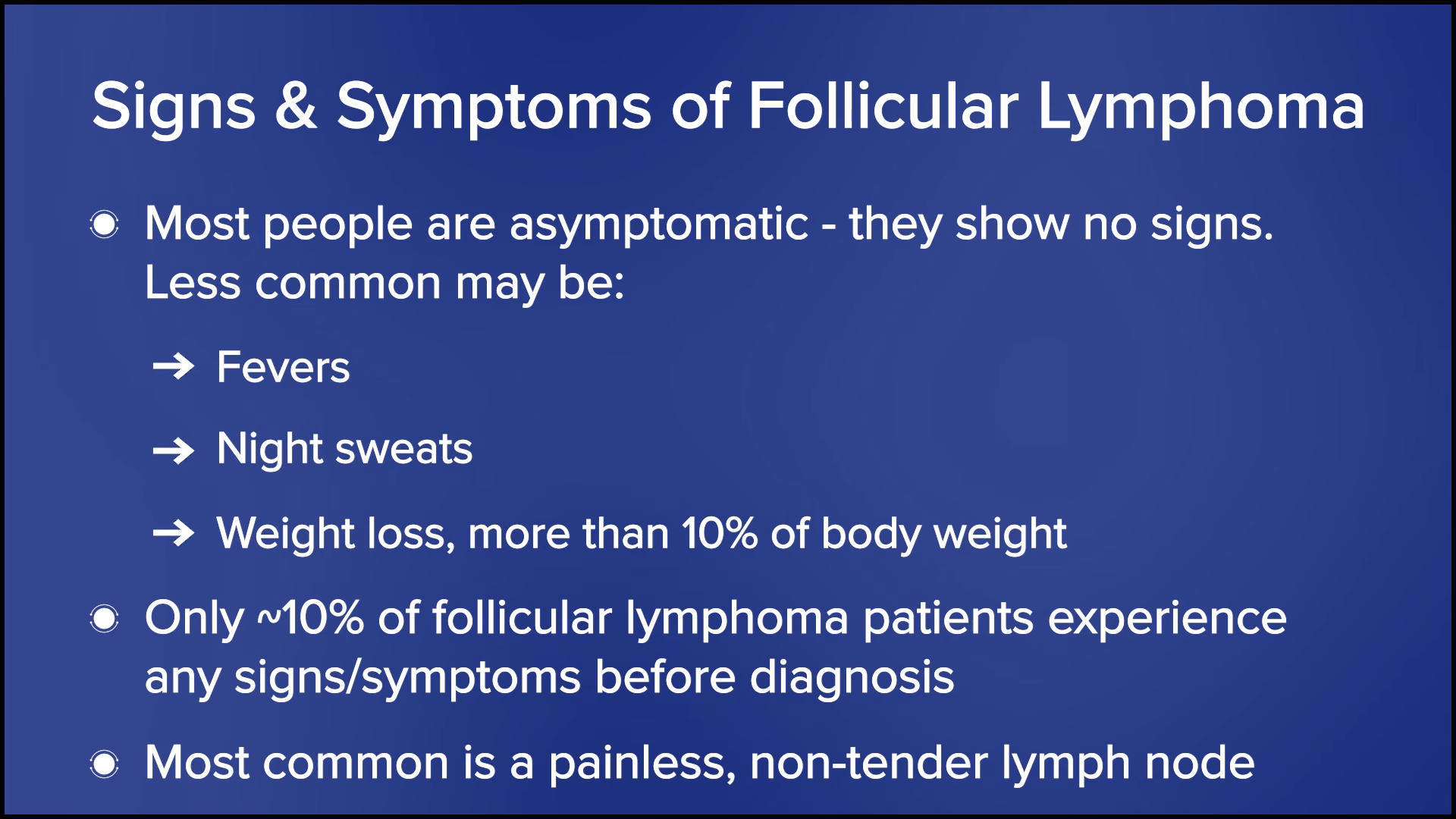

Dr. Brody: My grandma died at the age of 101. She didn’t have follicular lymphoma, but she had the next cousin over that we treated in a very similar way as other low-grade B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. We did watchful waiting for 37 years and never needed any therapy.

Most people are asymptomatic, but some people can have symptoms. The most common symptom of follicular lymphoma is a painless lymph node. The B symptoms, which are fevers, night sweats, and weight loss of more than 10% of your body weight, are pretty rare for follicular lymphoma and happen in less than 10% of patients.

Terminology: Watchful Waiting vs. Active Surveillance

Stephanie: Some people don’t like “watch and wait” as a term. It can be tough for so many people to be told they’ve got cancer but they don’t need to be treated right away. How do you describe that period to your patients? What term do you use? How often are people told that they’re on watchful waiting or active surveillance? What is the plan that accompanies that?

Dr. Brody: I grew up saying watchful waiting. Dr. Mike Schuster, a lymphoma doctor at Stony Brook, told me he patented the phrase “active surveillance.” I’m not sure if he patented the phrase, but it sounds a lot better. We’re going to actively surveil you as opposed to watchful waiting, which sounds like we’re going to sit around and do nothing. It’s all about branding.

The reality is we’re going to keep a close eye on you and how close depends on what’s been going on with them, how well you’ve known the patient, and for how long. This concept is super freaky to patients and their families when they first hear it. Some patients don’t get surveilled for that long, but every patient who is still on active surveillance a year later loves the concept. But on day zero, “Wait, what? Why aren’t you treating me? Cancer and no treatment sound super freaky.”

I come in with my grandma’s story, so they can hear that sometimes this can go for decades without needing therapy. The only test that tells you if you’re going to go down the same course is the test of time. There’s no test as good as that, but we’re going to watch you closely as we give you that test.

Dr. Bello: I usually use observation or keep an eye. Some people say that’s what they wanted to hear. Others say they’re getting a second and third opinion. They can’t take it and I feel for them. You have people whose lymphoma was picked up incidentally and you tell them, “We’re just going to watch you.”

Since these are picked up by accident, I always wonder if it would’ve been better if we picked this up 20 years later. Are we doing a disservice that we diagnosed this little lymph node under their arm? Should we have left it alone to begin with? They were living life peacefully and blissfully, and now they’re going to have 20 years of anxiety instead. The anxiety can sometimes be the hardest part of the diagnosis.

Standard Treatment for the First Two Lines of Therapy

Dylan: We’re going to dive into the treatment options, but before we go into the novel treatments, can you give us a breakdown of the standard treatment for the first two lines?

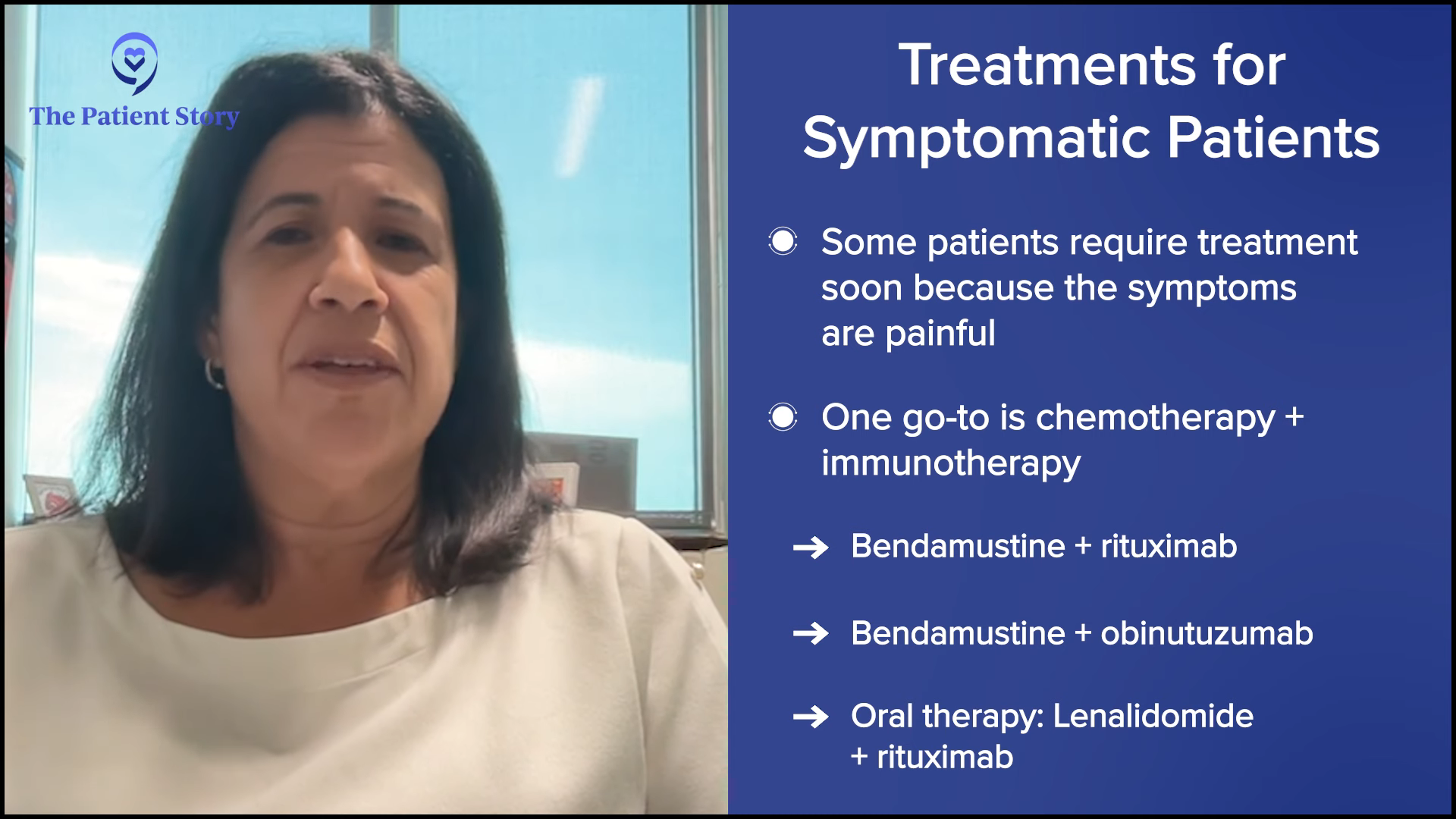

Dr. Bello: The standard is there’s no standard. That’s always the first problem, but it’s a good problem because we have a lot of different options. You like to base it on the patient you’re treating and your goal with treatment.

Some people may have one large lymph node that’s causing them discomfort, so radiation to that spot may be the best option. Some people may have generalized symptoms, like severe fatigue that’s interfering with some of their daily activities, but don’t have a lot of disease. In that case, you may want to give them a less intensive treatment, like a monoclonal antibody like rituximab, put the disease into remission, and see if it corrects their symptoms.

Other people are very symptomatic. They come to you with rapidly growing lymph nodes and have fluid build-up in certain body cavities like in the abdomen. You want to treat them with something that’s going to work quite quickly and that’s usually a chemotherapy plus immunotherapy regimen.

There are a few options available. One of the more popular ones is bendamustine plus rituximab or bendamustine plus obinutuzumab, which is another monoclonal antibody. There are also milder or non-chemo approaches, like oral therapy with lenalidomide and rituximab. The treatment has to be geared toward the patient you’re treating, fitness level, and treatment goal.

What are Bispecific Antibodies?

Dylan: Dr. Brody, what are bispecific antibodies? How are they different than CAR T-cell therapy? What’s their mechanism of action?

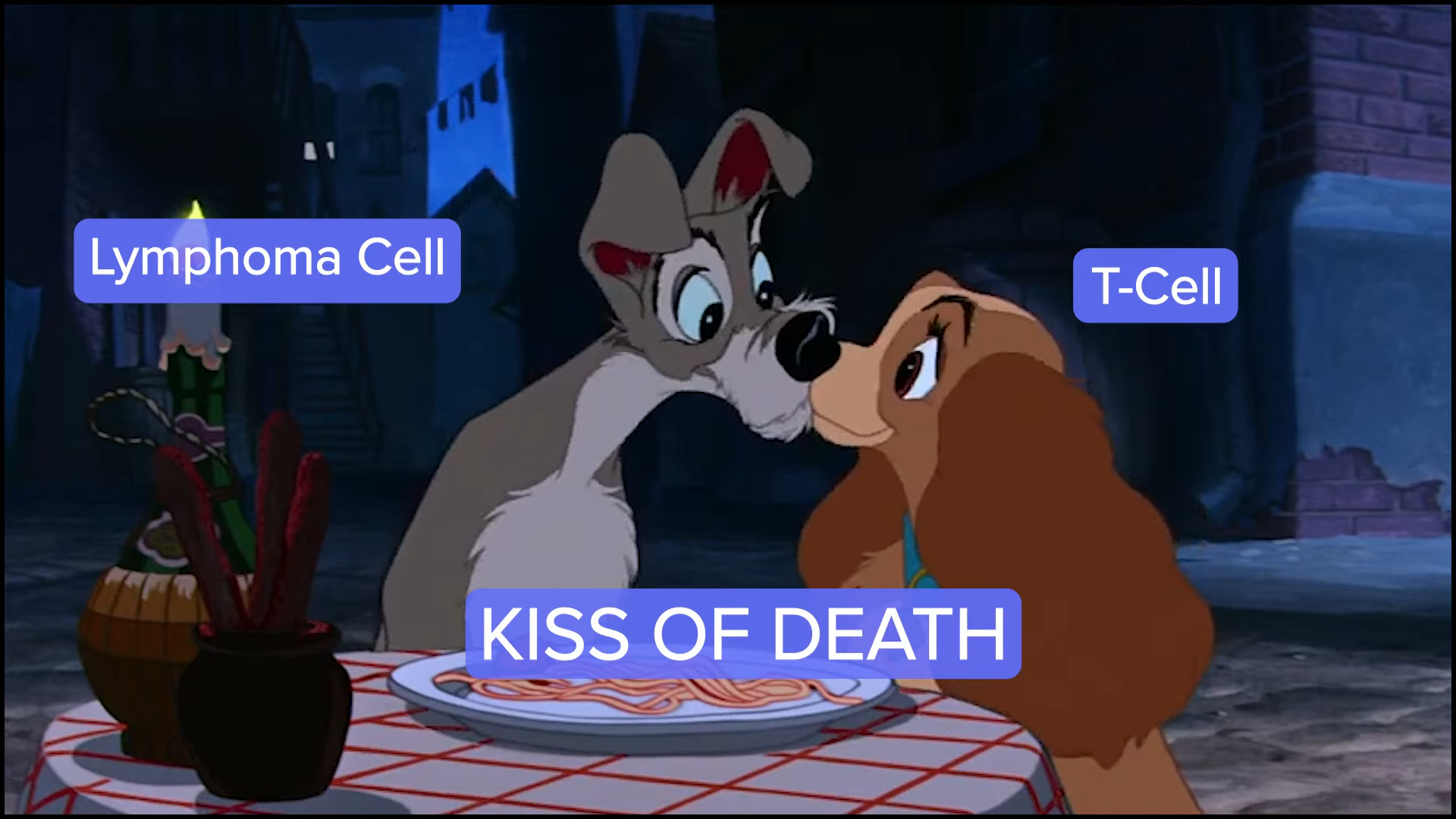

Dr. Brody: Dr. Bello mentioned that one of our go-to therapies over the last 24 years is monoclonal antibodies, anti-CD20 antibodies, especially rituximab and obinutuzumab. Rituximab is certainly the most famous. It’s an anti-lymphoma antibody. CD20 is one protein marker on the surface of lymphoma cells. CD3 is a marker on T cells. Bispecific antibodies are two of those antibodies.

In Lady and the Tramp, when the puppies were sucking from the dish at the same time and ended up accidentally sucking on the same noodle, it brought the two of them together. Now instead of that, it’s the kiss of death where the lymphoma cell and the immune cell are brought together by the bispecific antibody and it activates the immune cell at the same moment so the T cell kills the lymphoma cell. I think it was Dr. Matthew Lunning at Nebraska who made up the Lady and the Tramp reference.

T cells are incredibly good at killing lymphoma cells, better than probably any other cancer. It’s the same idea as CAR T-cell therapy. The main difference is that we have to take the T cells out of the person, ship them somewhere, get the CAR T cell made, and have it shipped back. A bispecific antibody is in some ways an off-the-shelf version of that, so you can use it today.

They’ve been incredibly effective at melting away lymphoma cells, even when other therapies like chemotherapy, lenalidomide, and a few others have not been working, especially when rituximab has not been working. Still, these bispecific antibodies have been awesomely effective in inducing remissions in the great majority of follicular lymphoma patients. It’s been an absolute revolution. That is not an overstatement because we didn’t have anything nearly as effective and safe as this until bispecific antibodies came along.

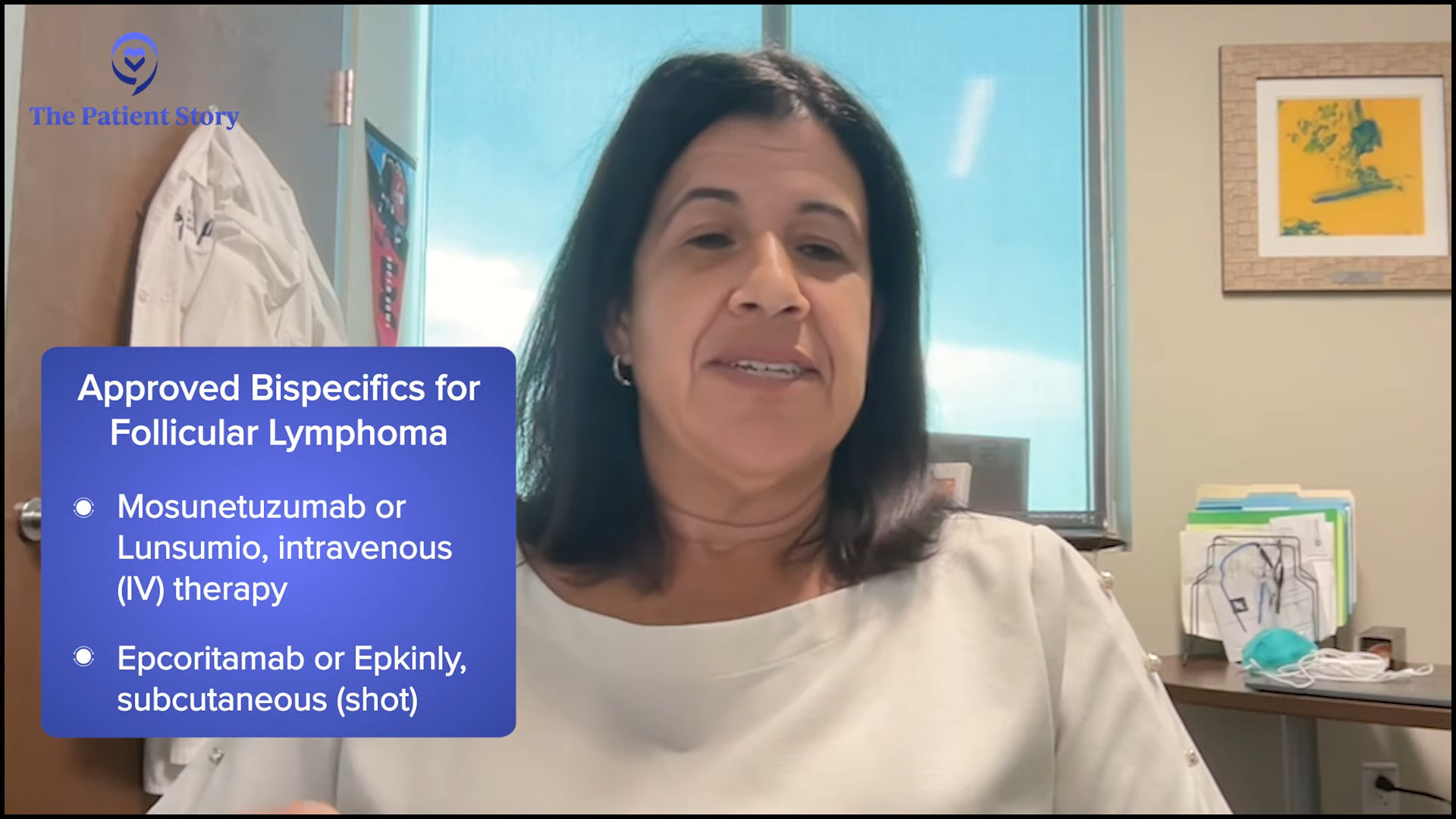

Approved Bispecific Antibodies for Follicular Lymphoma

Stephanie: We have two FDA-approved options in follicular lymphoma so far. Dr. Bello, for what kinds of patients would you recommend bispecific antibodies? Is there anything practice-shifting for you?

Dr. Bello: For follicular lymphoma, we have mosunetuzumab and epcoritamab. Thankfully, the majority of these lymphomas are pretty indolent and respond very well to front-line treatment, whatever you use. You can use chemoimmunotherapy, like bendamustine and rituximab or obinutuzumab, both of which are monoclonal antibodies. We have the luxury of having a lot of patients who don’t end up needing to get a bispecific antibody.

But for patients who progress, we have these immunotherapies: bispecific antibodies and CAR T-cell therapy. I use bispecific antibodies in people who have progressed after two lines or more of treatment. I always try the other lines first, unless we have a clinical trial because they’re proven and have a great track record. I don’t skip straight to a bispecific.

Bispecific antibodies have some side effects that are very unique to them and may not be the best for everybody. They also require a little bit more skill in monitoring them. They are administered in the hospital at the beginning and in the office for the subsequent doses.

Stephanie: Dr. Brody, what about you? How do you approach bispecific antibodies and how do you decide to use one over the other?

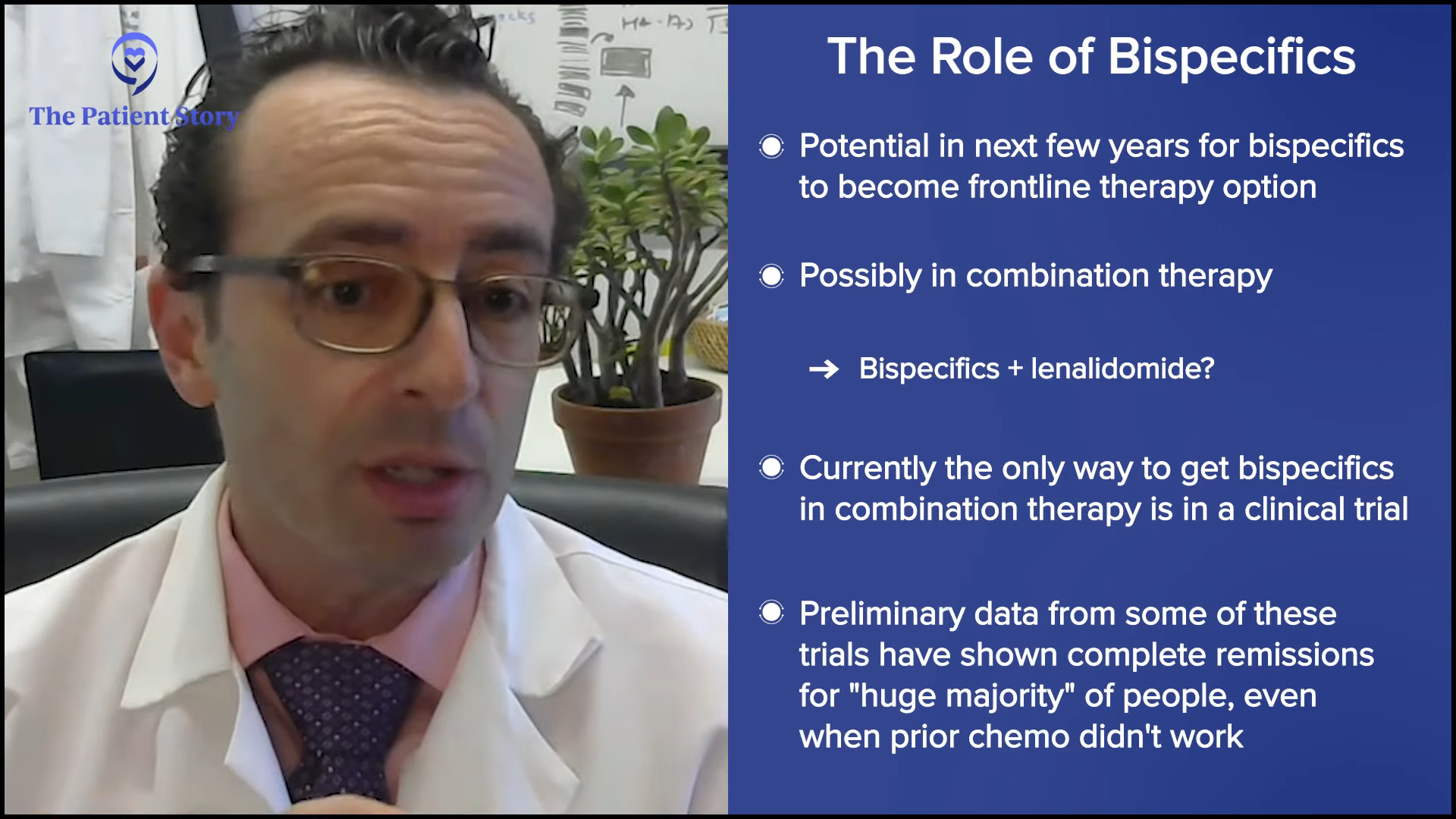

Dr. Brody: We’re very lucky to have two FDA-approved options. Their roles are evolving very rapidly and will be evolving very rapidly over the next few years. I would expect that five years from now, bispecific antibodies will be an option for front-line therapy. They may be given as a monotherapy, but honestly, I don’t think that’s their future. I think the future is like rituximab, which is to become part of combination therapy.

Dr. Bello was doing some comparison between CAR T-cell therapy and bispecific antibodies, and I agree very much with what she was saying. But in the future, it may be an irrelevant comparison because it won’t be what’s better between CAR T-cell therapy or bispecific antibodies. It’ll be an apple and orange comparison. Who cares what’s better?

In the future, we probably won’t be giving bispecific antibodies by themselves. Today, they’re only FDA-approved to be given by themselves, so the only way to get them as part of a combination is through a clinical trial. The preliminary data from some trials of bispecific antibodies plus standard therapies have been awesome with the huge majority of people getting complete remissions in some cases, even when prior chemotherapy and such weren’t working.

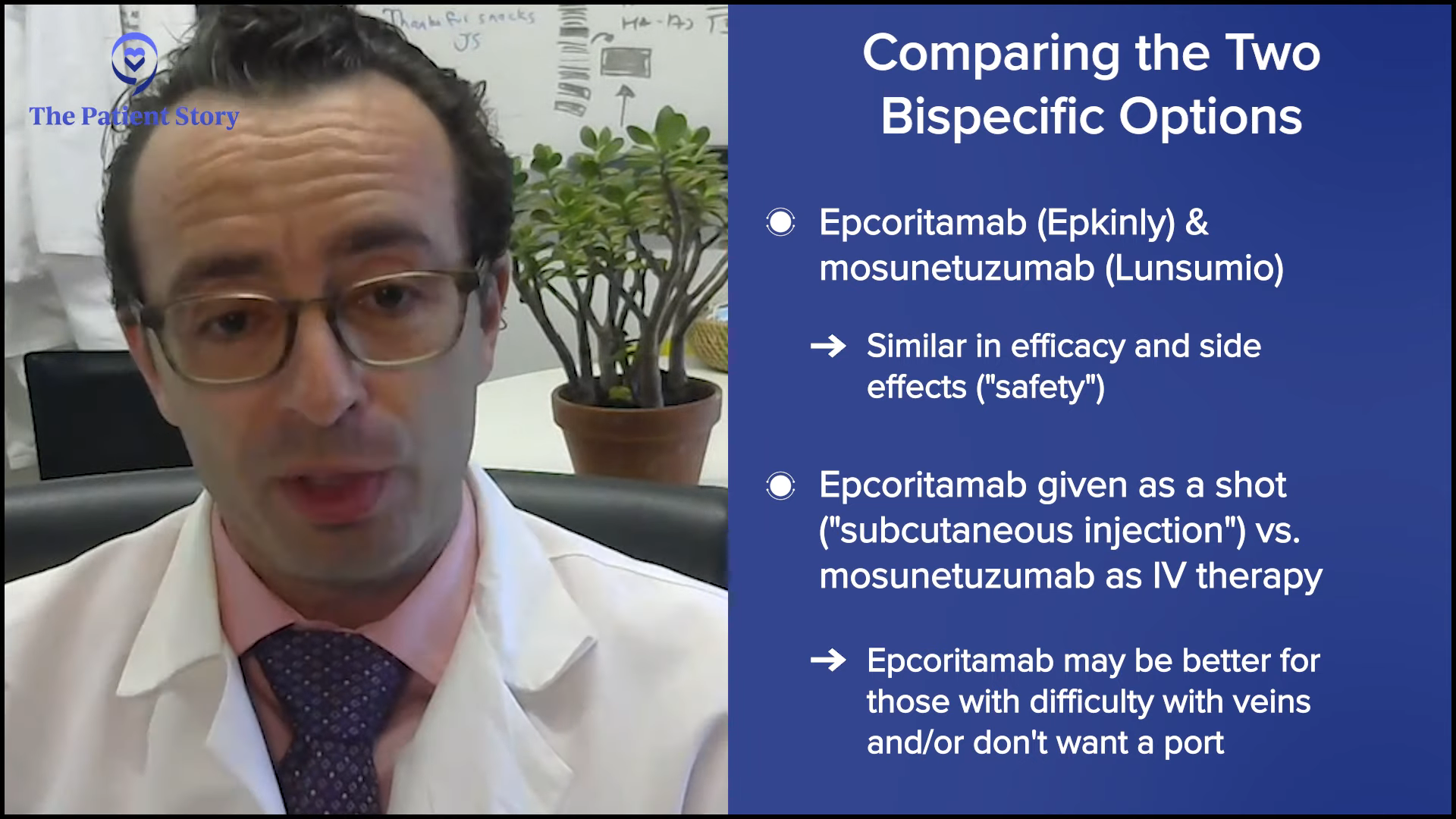

Medically, mosunetuzumab and epcoritamab are pretty similar. They have pretty similar efficacy and pretty similar safety profiles. Epcoritamab is given subcutaneously and mosunetuzumab is intravenously. For many patients, it doesn’t make a difference. For some patients, especially those who have had multiple prior lines of therapy and whose veins have gotten beat up, it does make a difference to them. Some patients have a port that they don’t want to have anymore or they don’t want to get a port.

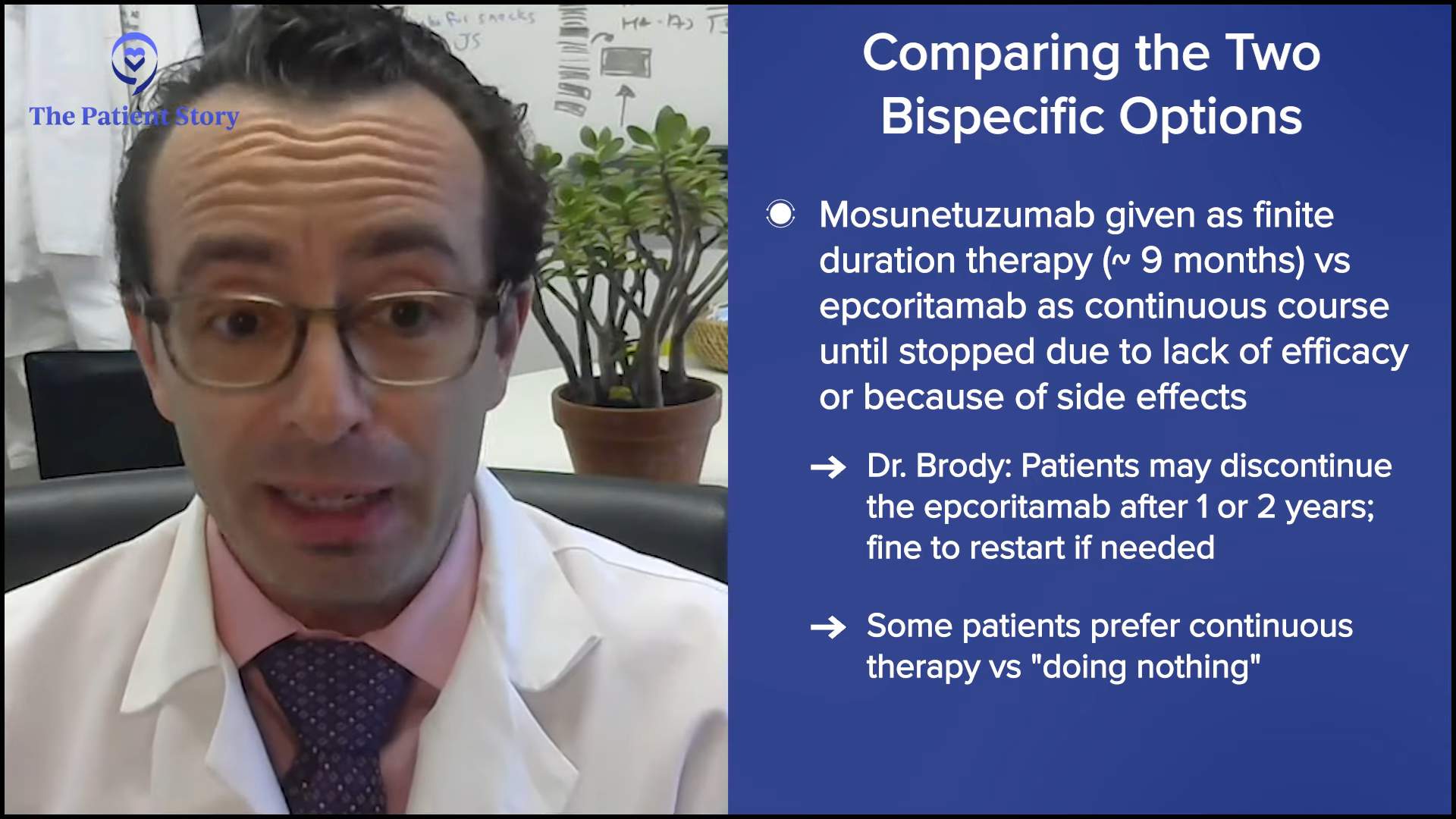

Another difference is that mosunetuzumab is a finite course of therapy, about nine months, while epcoritamab can be given until it stops working or until you have a bad side effect. We have a lot of patients who have been on it for a year or two and say they want to pause for now, and we’re okay with that. It’s not exactly the recipe as written, but we don’t feel like we’re burning any bridges because if the lymphoma were to grow back, we might be able to treat them again. Some patients prefer to keep going because they don’t like the notion of doing nothing.

Because it’s more about the total doses of epcoritamab, for me, it’s simple. If I have a patient who lives across the street and they don’t want any IV therapy, that patient gets epcoritamab. If the patient lives four hours away and feels strongly about not making too many trips and doesn’t mind getting IV therapy, that patient gets mosunetuzumab. Patients have a big role in that decision.

Dr. Bello: I still prefer CAR T-cell therapy over bispecific antibodies because I see more durable responses, but not everybody can wait to do the whole process. As Dr. Brody mentioned, you have to collect the T cells, send them to be manufactured, and wait for them to be sent back. By then, four to six weeks have gone by and if they’re having rapid progression, they can’t wait.

CAR T-cell therapy can have a little more toxicities with them. Patients are hospitalized a bit longer, so not everybody has a performance status that’s robust enough. That’s when I would use the bispecific antibodies.

Common Side Effects of Bispecific Antibodies

Dylan: Dr. Bello, you touched on the side effect profile of bispecific antibodies. If I was a caregiver or a patient, what should I be on the lookout for and what would my experience be like?

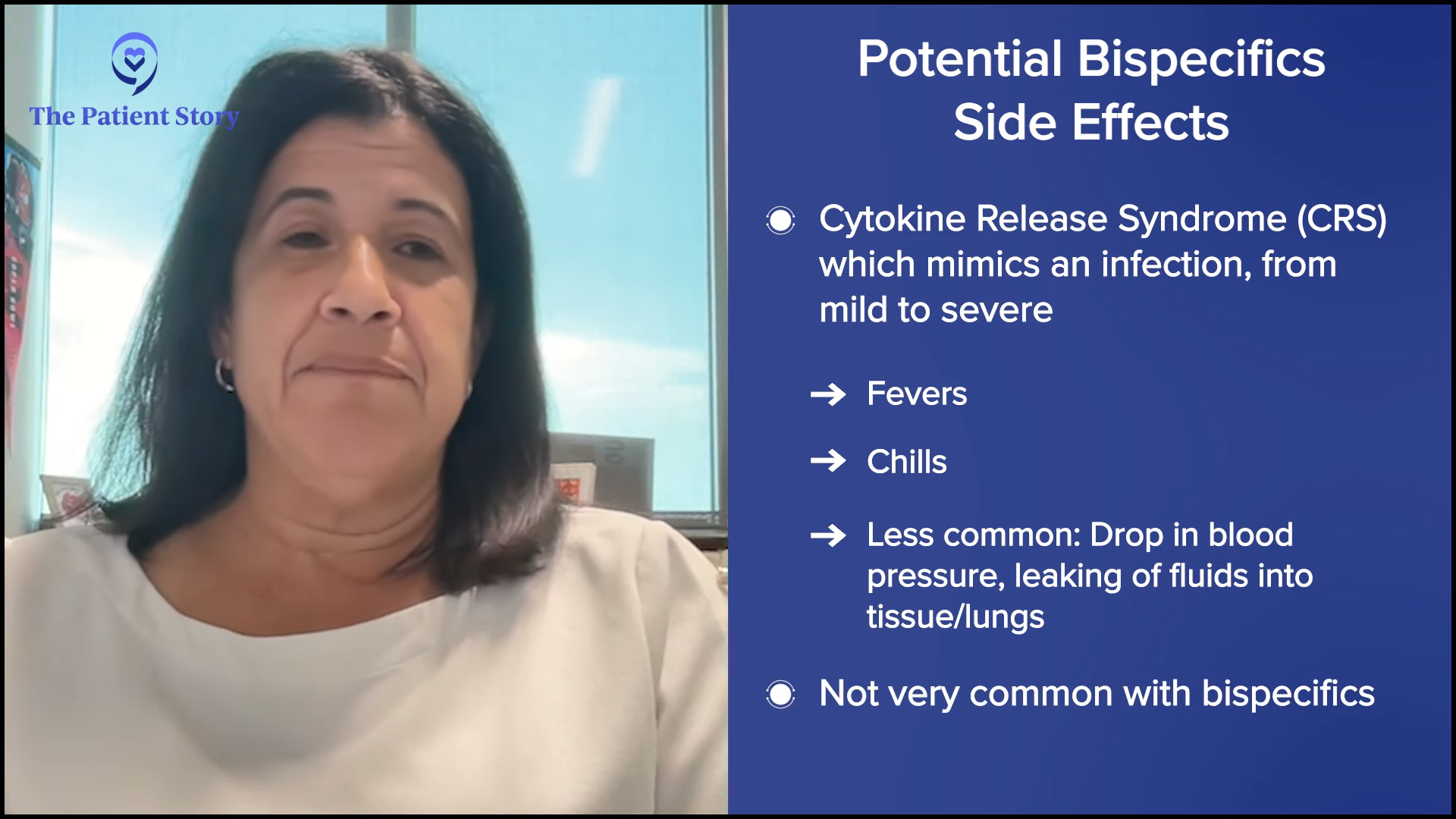

Dr. Bello: A lot of people are now familiar with cytokine release syndrome (CRS). It mimics the most severe infection you’ve ever had with symptoms including fevers and chills. Sometimes, it can be more severe. Patients can have a drop in blood pressure. There can be fluids leaking into the tissue and lungs.

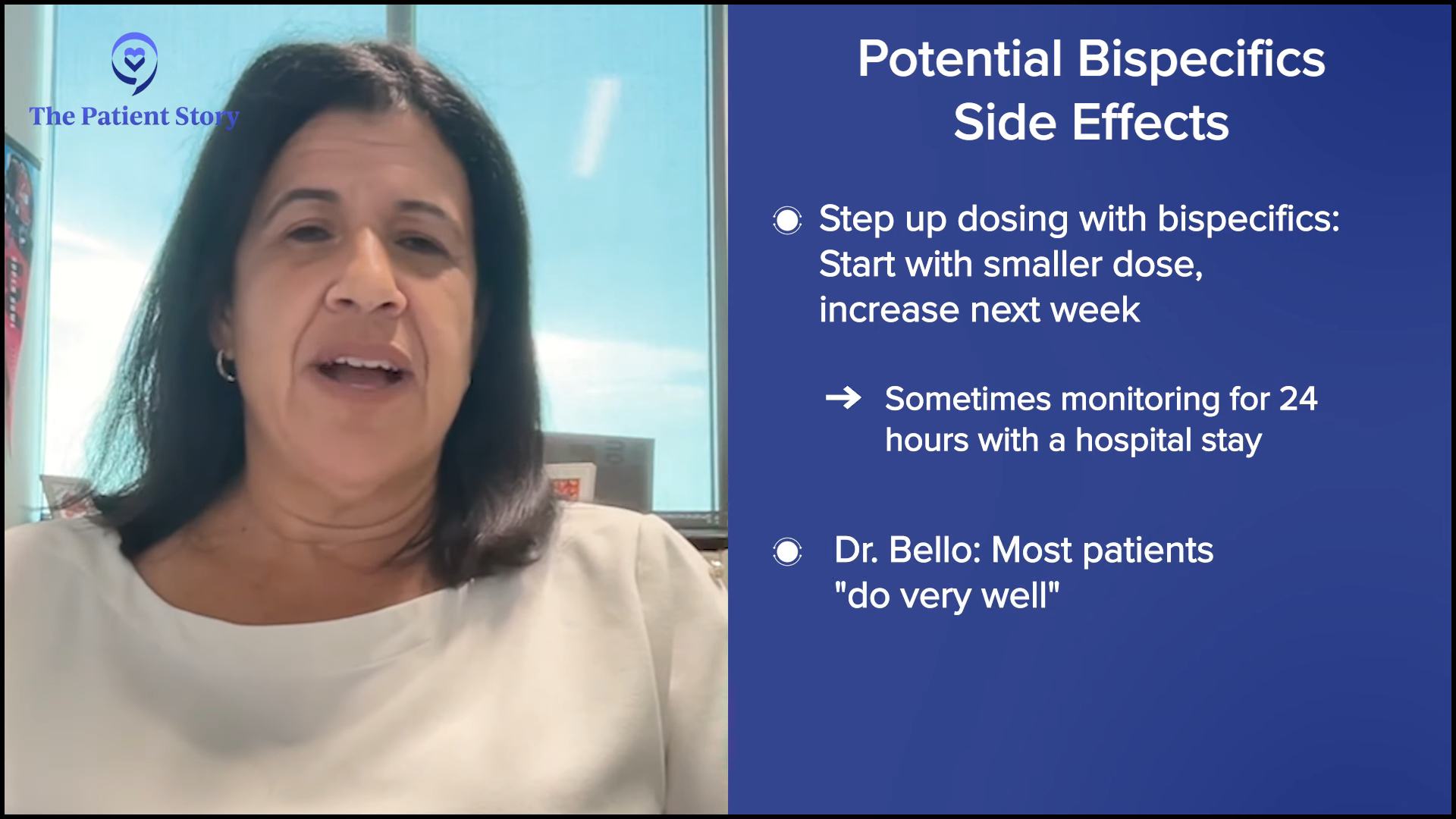

Bispecific antibodies don’t cause much of CRS in most people, so it’s nice that we err on the side of caution. We do it in step-up dosing where we start with a small dose, have the patient come back a week later and give them an increase, then a week later, another increase. Sometimes we hospitalize them to monitor them for 24 hours, but the majority of the time, they do very well.

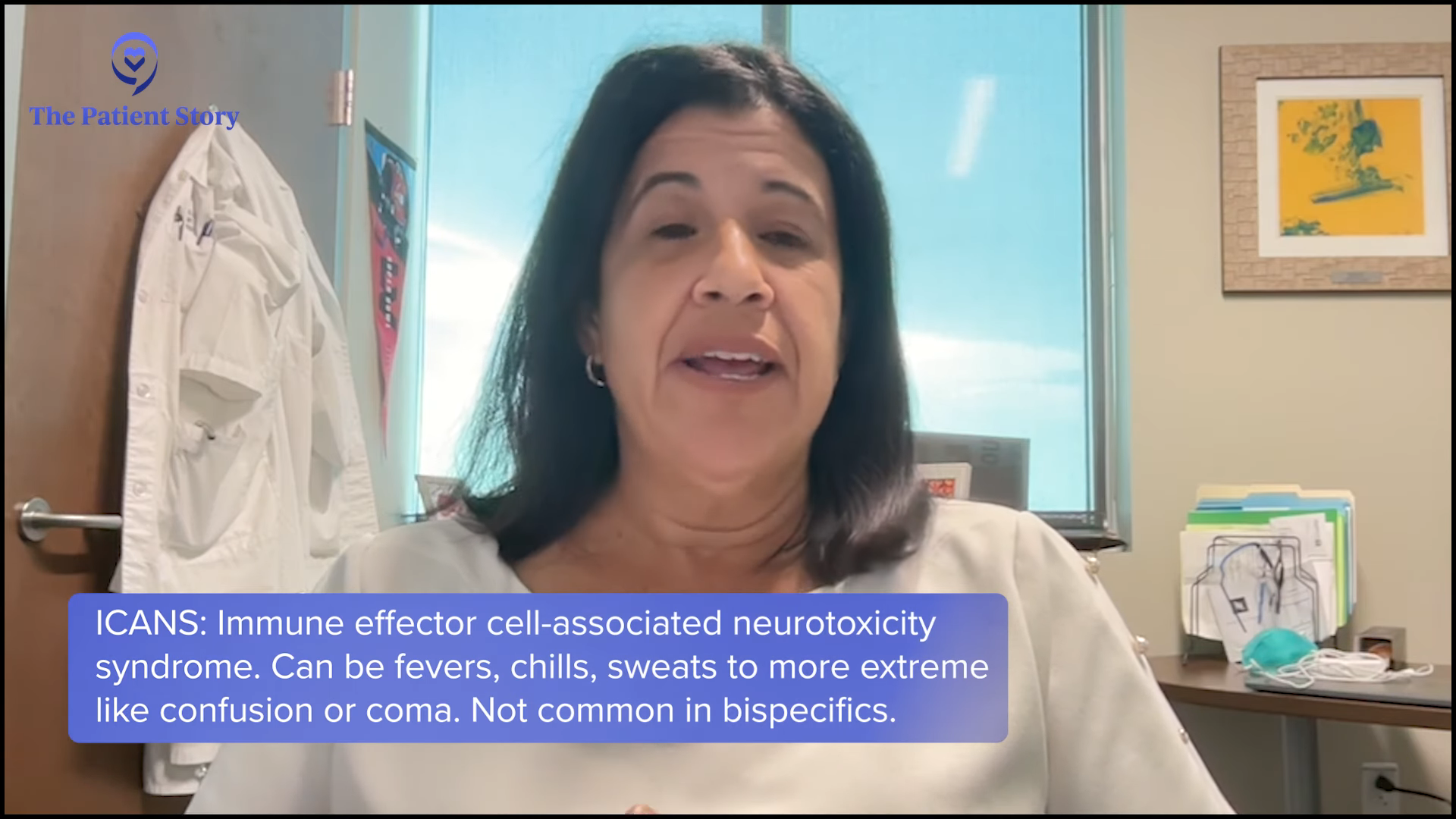

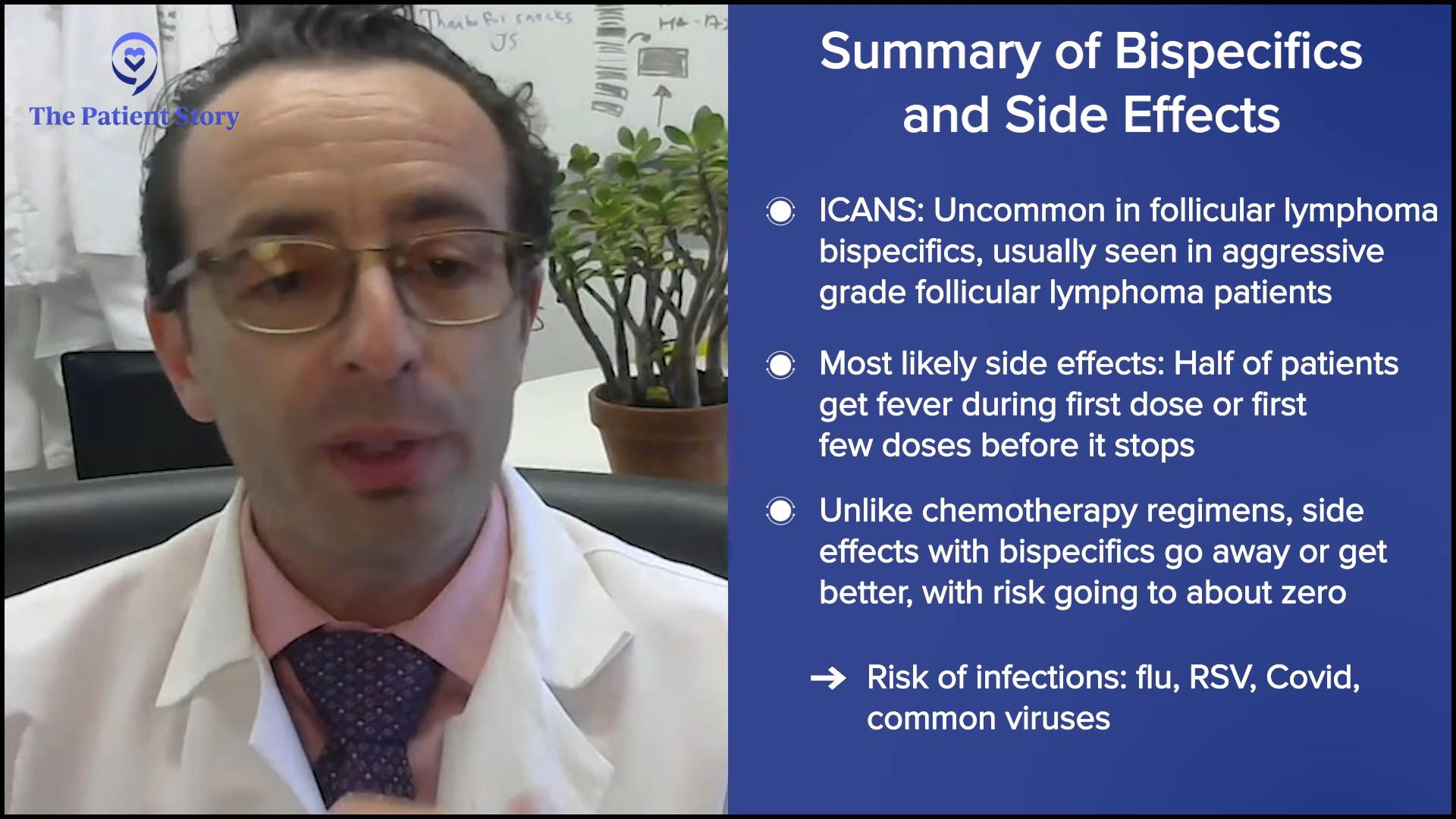

Neurologic toxicity or immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS) is more serious. It can present as confusion, word-finding difficulties, or as severe as being obtunded or in a coma. Again, we don’t see much of it with bispecific antibodies so fortunately, it’s not something we need to look for. We let patients know about the possibility, but we don’t usually see that.

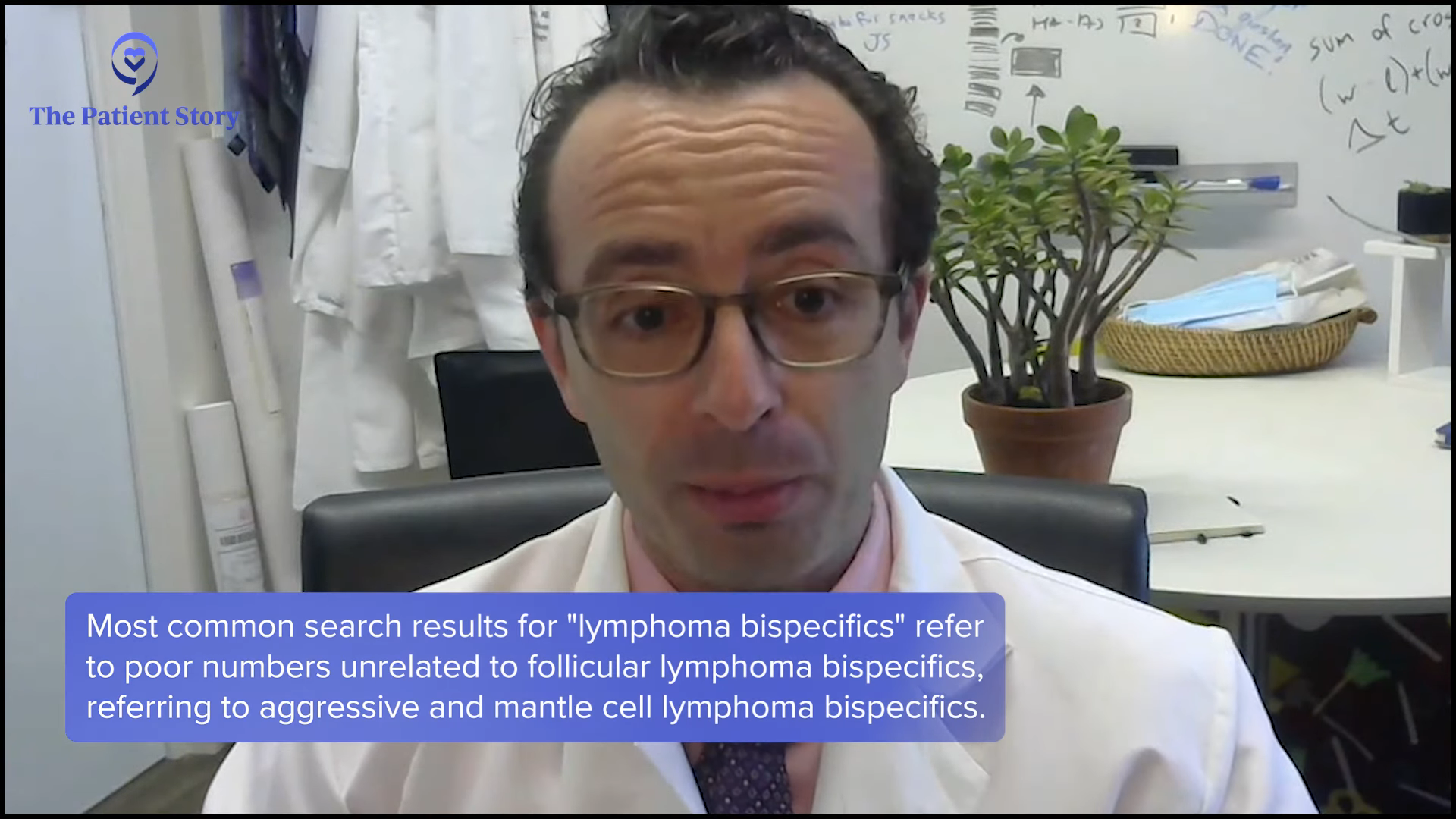

Dr. Brody: Dr. Bello was very thoughtful in reminding people that this can be severe, so the patient and, even more importantly, the caregiver needs to know it can be severe. But then we also like to tell people about the reality and the statistics. If they read too much on Google, they’ll unfortunately also read about aggressive lymphoma bispecific antibodies and mantle cell lymphoma bispecific antibodies where the numbers are a little bit worse. But with the follicular lymphoma bispecific antibodies, almost all of these CRS incidences are low-grade.

Similarly for ICANS, in the biggest studies for follicular lymphoma patients, it was the high-grade version of that where people were confused. There was 0% in all of the recent studies, so we do have to tell people about that. At the same time, we want to tell them not just what might happen but what likely will happen. What likely will happen is about half of patients get a fever and they get it either on the first dose or the first few doses.

If a person is getting many more doses in the future, they rarely happen. Most side effects of cancer therapies get worse as you go, like with chemotherapy. Bispecific antibodies are the opposite. It’s the first couple of weeks that have the risk of fevers and then that risk goes down to about zero. I don’t want to say there are no risks because there still are some risks. The risk of infection from common viruses like the flu, RSV, and COVID are real, but they’re true for almost every therapy we give and even for some lymphoma patients who are not even on therapy. Those are the common risks that most of us are facing.

The main thing is cytokine release syndrome and neurological side effects mostly happen in the first few weeks or never happen at all. In that way, it’s a bit of a comfort to a patient because once they get through the first few weeks, I don’t want to say they’re in the clear, but they’re definitely in the easy running part.

Access to Treatment

Stephanie: When CAR T-cell therapy first came out, there were some issues with access in that it has to be done at very specific places. What are your thoughts about bispecific antibodies and access to them?

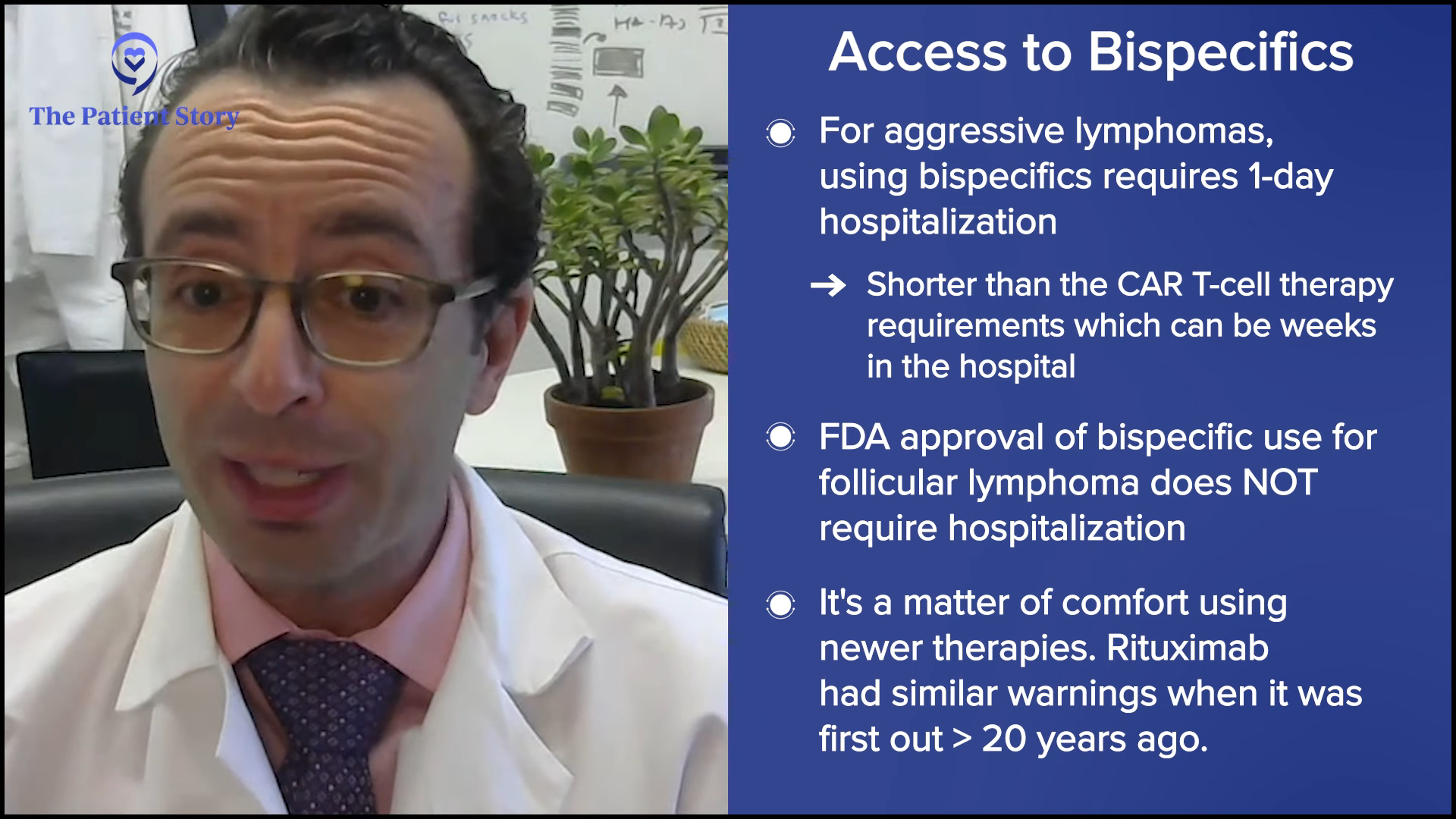

Dr. Brody: That’s supposed to be the main transformation and revolution about bispecific antibodies. They’re supposed to be accessible and they are or definitely will be. Let me make a little distinction.

For aggressive lymphoma bispecific antibodies, there’s one little speed bump: the ones that are approved now require a one-day hospitalization. One day in the hospital isn’t that bad, but that becomes a real pain for the doctors who have to coordinate that. Even though it’s not a big deal medically , it’s a logistical pain in the butt. Still a lot easier than CAR T-cell therapy, where the patient can spend weeks in the hospital sometimes, but it’s still not nothing.

By contrast, no hospitalization is required for the follicular lymphoma bispecific antibodies (epcoritamab and mosunetuzumab), based on the FDA label and the way that we do it. We occasionally will have an elderly patient we are worried about, so we’ll admit them to be safe, but for most patients, no hospitalization is required. That makes the accessibility hugely more doable than CAR T-cell therapy or even bispecific antibodies for aggressive lymphoma.

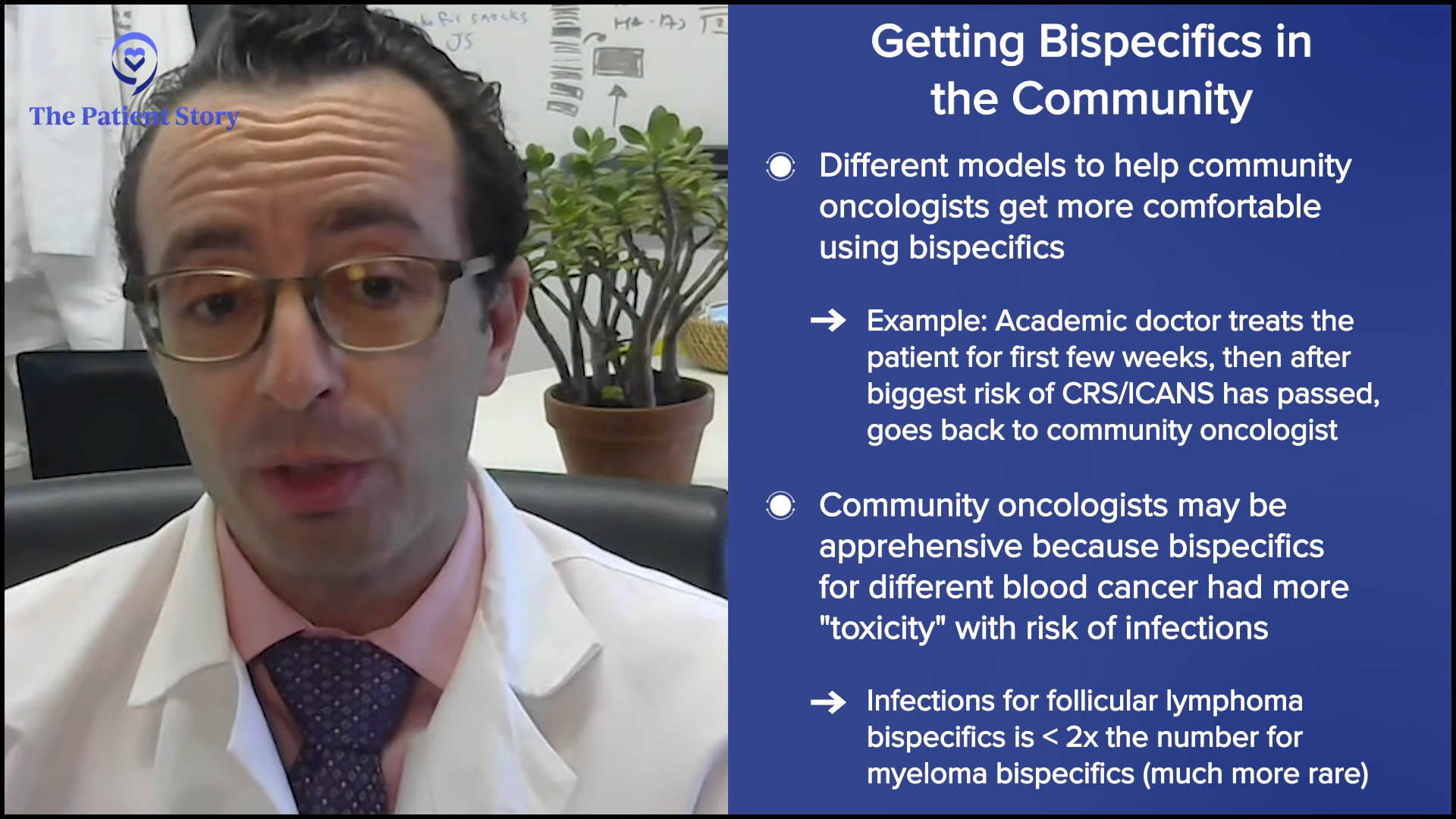

The main obstacle to accessibility is community oncologists getting comfortable with these. They’re recently FDA-approved, so they haven’t used them a lot before. Doctors like Dr. Bello and I have been using these for years as parts of clinical trials, so we’re pretty comfortable with them. Like Dylan said, rituximab sounded scary when it was first released and people having infusion reactions was a big deal. Now, no one’s surprised by infusion reactions and everyone’s comfortable with it.

I think it’ll be similar with bispecific antibodies. The hurdle to accessibility is community oncologists getting comfortable with them. There are different ways to facilitate that. One version is the academic doc treats the patient for the first few weeks until they get over that little hump of the risk and then we send them back to their community oncologist. They don’t have to drive back and forth so much. In a couple of years, community oncologists will be very comfortable with these, so it will be less of an obstacle.

Dr. Bello: I agree. Like all drugs, once they’re out for a few years and people have become more comfortable with them, they’ll become more readily available at multiple locations.

Differences Between Bispecific Antibodies and CAR T-cell Therapy

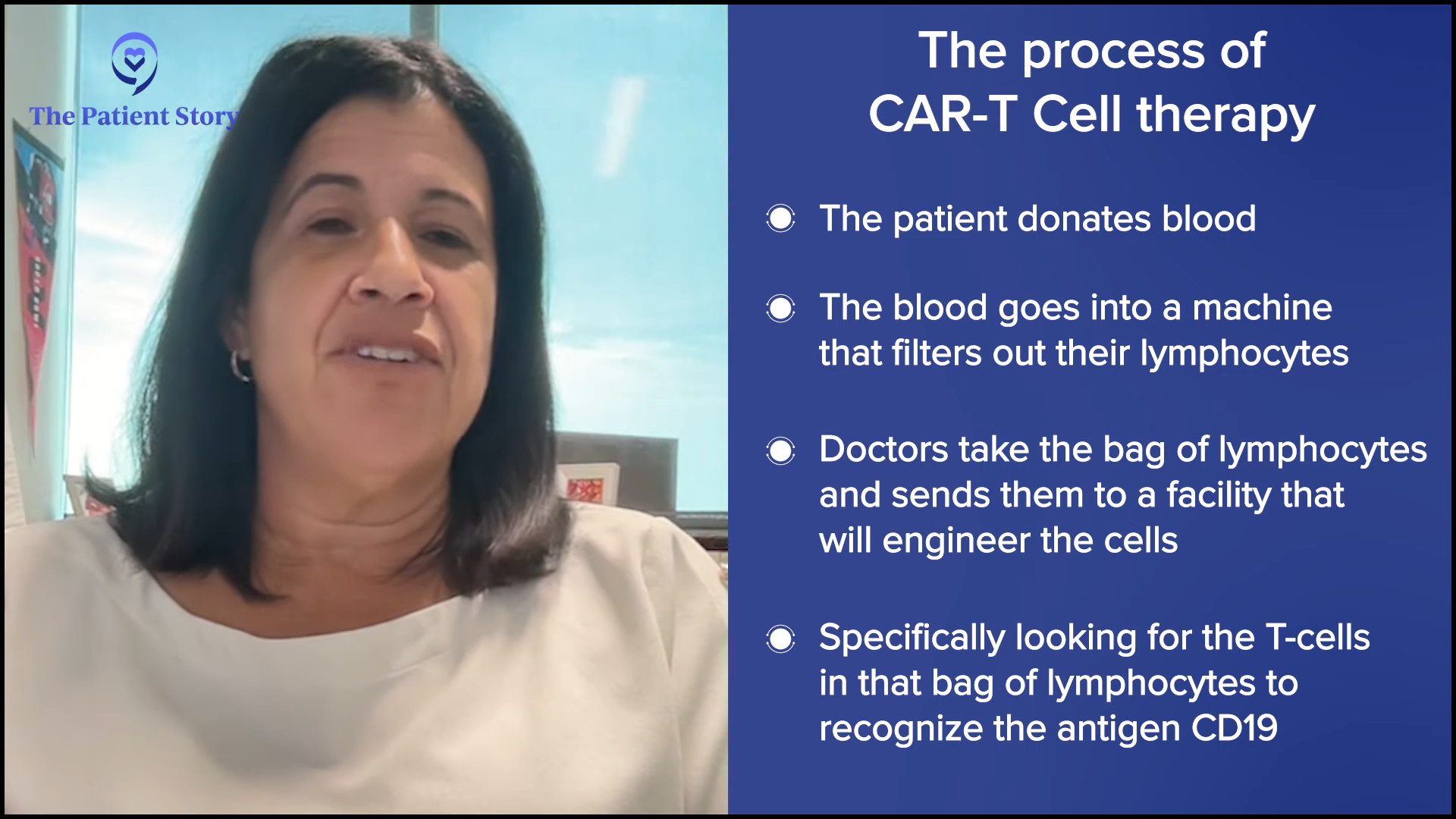

Dylan: CAR T-cell therapy is still a major player. We have three FDA-approved options—liso-cel, axi-cel, and tisa-cel—and tons in the pipeline targeting anything you can find. We talked about bispecific antibodies. What’s the difference between them and CAR T-cell therapy, and the mechanism of action for CAR T-cell therapy?

Dr. Bello: As Dr. Brody mentioned earlier, they’re similar, but the mechanism of action is obtained differently. CAR T-cell therapy is a much more complicated process. Patients come in, they donate blood, and a machine filters out their lymphocytes and gives them their whole blood back. Their lymphocytes are sent to a facility that will engineer the T cells to recognize a marker on the lymphoma cells. In the three products that you mentioned, the marker is an antigen called CD19, which is pretty much common in almost all B-cell lymphomas.

In addition to the T cell being able to recognize that antigen, the T cells are also programmed to be turned on. By nature, when T cells are in your body, they’re not attacking your body randomly. They need a trigger to turn them on. These T cells are engineered to recognize a certain antigen in the lymphoma cells and they’re activated already.

When they’re ready, they ship them back. Usually, it takes a couple of weeks for them to do this. The patient comes in and we give them a moderate dose of chemotherapy over a couple of days to suppress their immune system and then we give their T cells through a transfusion.

Once they get into the body, they immediately start to attack the lymphoma. A lot of times, we hospitalize people for this portion because now is when they start getting cytokine release syndrome or neurological toxicities. We monitor them in the hospital because there are tests we can do to see if they’re going to start getting more severe symptoms. We also have some medicines we can use to attenuate some of these if they start happening.

Patients are in the hospital anywhere from seven days to three weeks, depending on how long the inflammatory process lasts. It can start as soon as the cells are put in or it can start a couple of days later, so we don’t let them go home within 24 or 48 hours. There’s a peak in the symptoms and then you’ll start to see the inflammation lessen, the patients start to get back to their baseline or their normal status, and then we eventually let them leave the hospital.

Obviously, their work is not done because, at that point, their blood counts will be low. Even though it’s an immune therapy and we think that it’s attacking the lymphoma cells, it does cause quite a bit of a drop in the white cells, red cells, and platelets. Some of these patients require transfusion support during the first few weeks after and antibiotics because we see infections happen because of the low white cell count.

What I always found weird with CAR T-cell therapy is sometimes people get very sick for a few days and then it’s like a light switch is turned off. All of a sudden, the inflammation stops. Once the inflammation lessens, the patients start to get back to normal. I always tell them they’re going to have a week of hell and then they’re going to feel all right afterwards.

Dylan: I’m glad you said that because these neurological symptoms can be terrifying. For the patient, it’s going to be a blur most of the time, but for the caregivers, it’s the most terrifying thing in the world.

Dr. Bello: It’s good to let them know because there’s some misconception that CAR T-cell therapy and immunotherapies are benign. They come into the office saying, “I don’t want chemotherapy. I want CAR T-cell therapy.” No, we’re not going straight to that. There’s a misconception that because it’s not chemo, it must be easy. It’s an intense treatment. It’s not going to be a walk in the park.

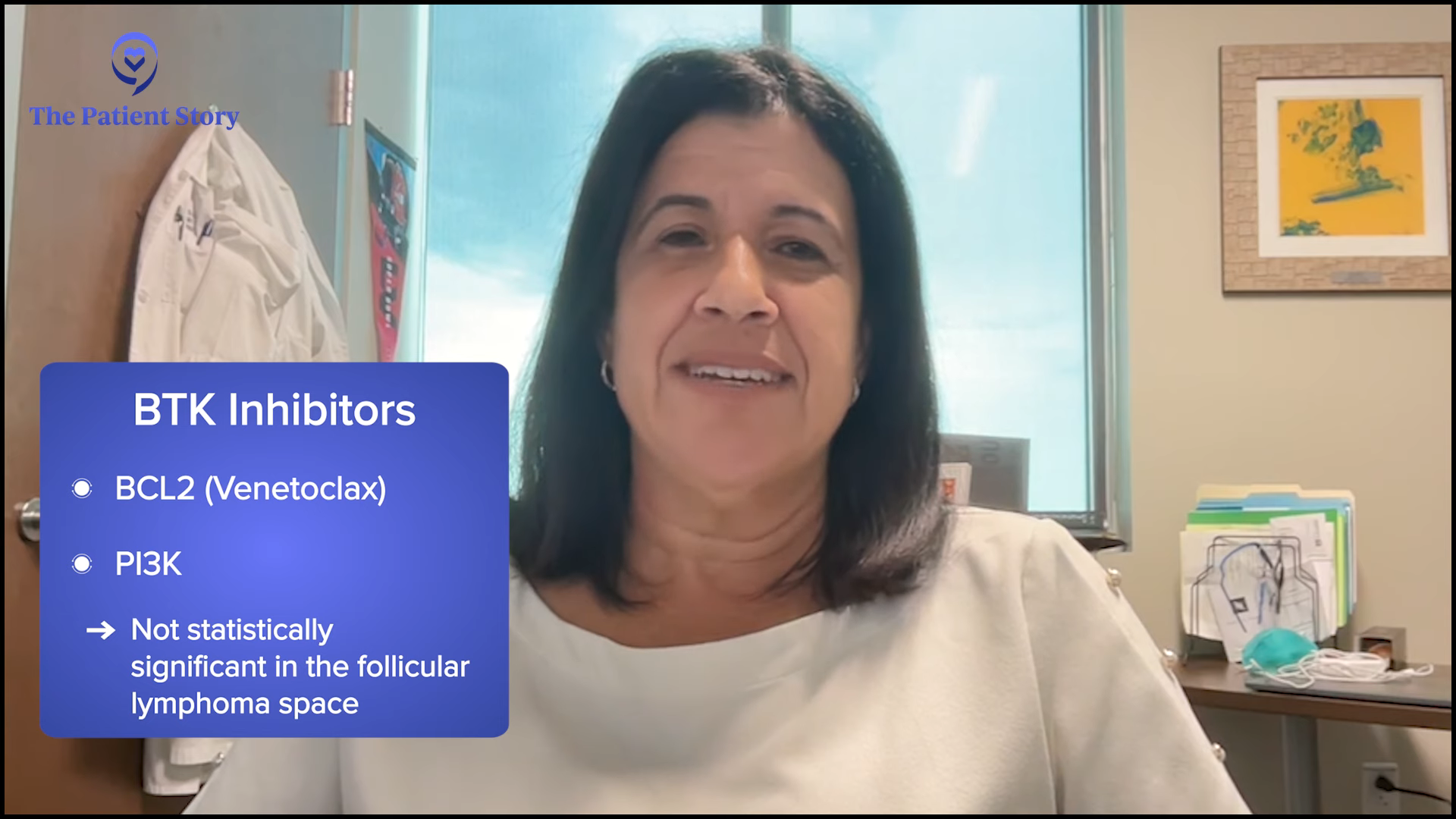

The Role of Inhibitors

Dylan: Probably the most confusing for patients are the inhibitors. There’s BCL2, BTK, and SYK, and some of these are FDA-approved. Where do those fit into this new paradigm with CAR T-cell therapy and bispecific antibodies? Dr. Bello, how do you use them in your practice?

Dr. Bello: Unfortunately, the data with BTK inhibitors in follicular lymphoma has not been the greatest. BTK inhibitor stands for Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitor. We use them a lot for other types of indolent lymphomas, like small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL), chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), and Waldenstrom’s, but with follicular, it hasn’t worked that well. There are some studies in development looking at BTK inhibitors in combination.

The other one is the BCL2 inhibitor venetoclax. That one is still a shocker to me. BCL2 is what’s mutated in 99% of follicular lymphoma and this drug that blocks the BCL2 pathway doesn’t work in follicular lymphoma.

The one that had the best results, PI3K inhibitors, was pulled from the market. Thankfully, we have these other options that I don’t miss them too much.

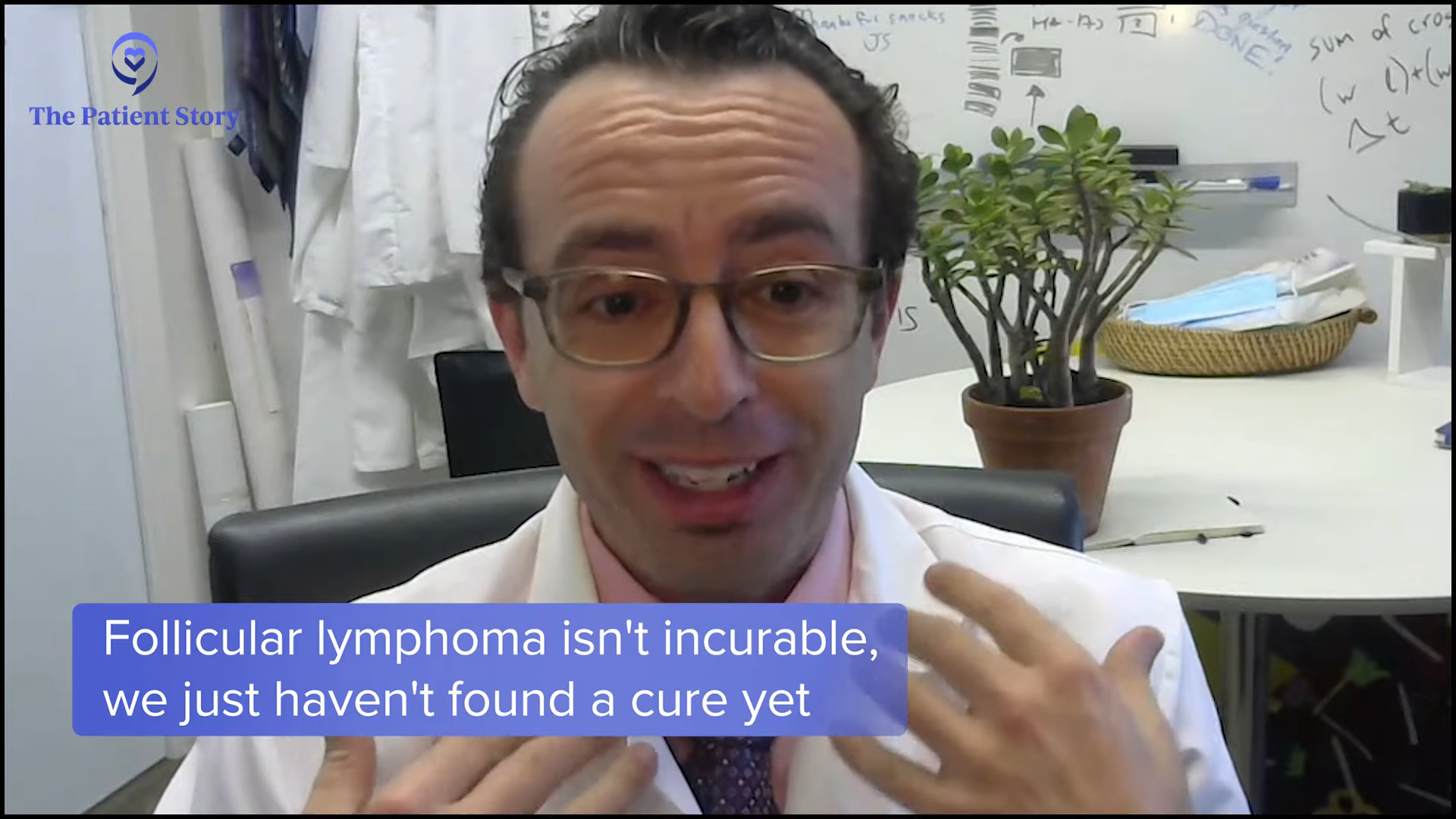

Cure vs. Longer Periods of Survival

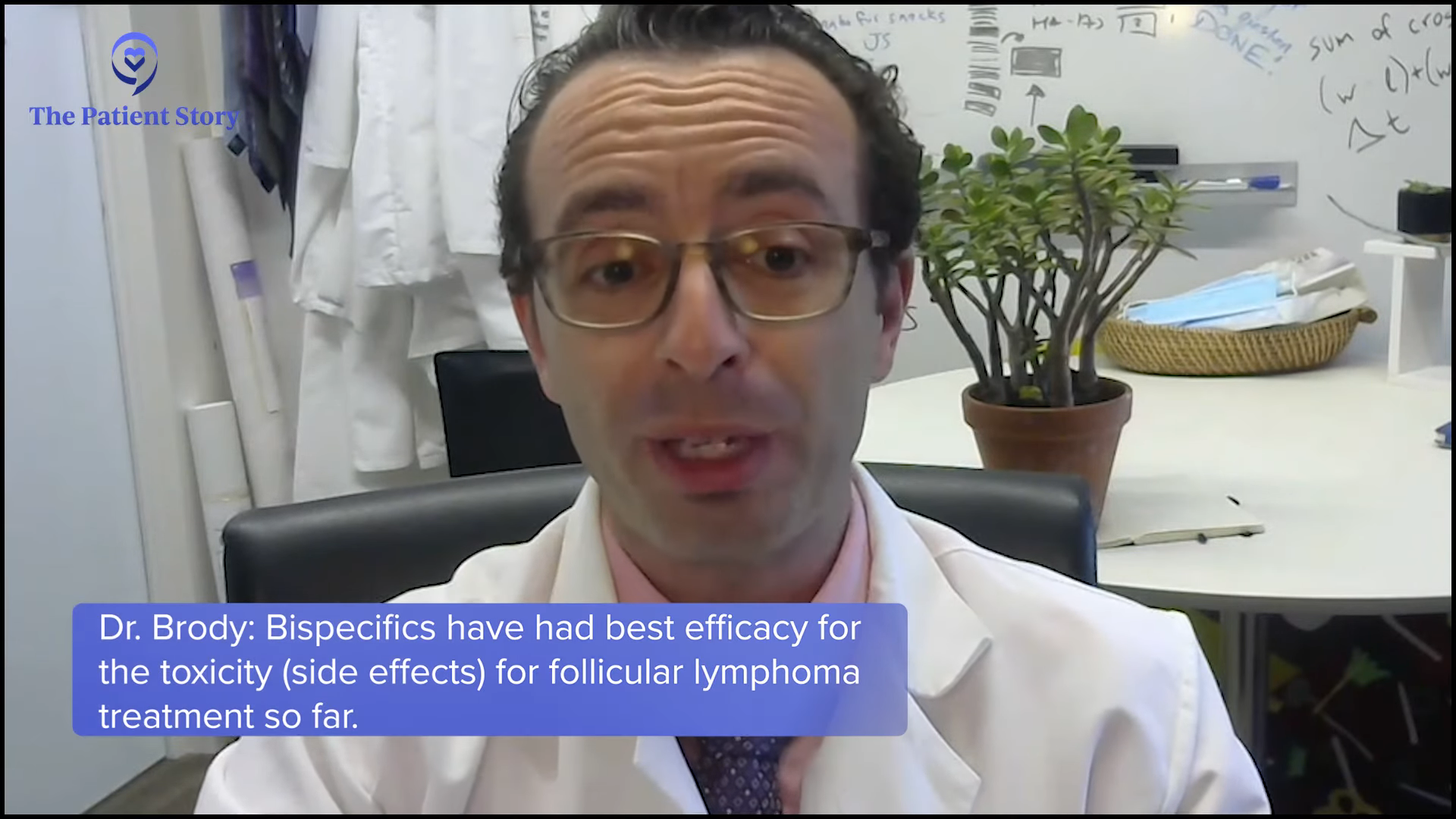

Stephanie: Dr. Brody, there’s so much development happening in the immunotherapy space, like CAR T-cell therapy and bispecific antibodies. I know doctors don’t like using the word “cure,” but is there a discussion about that? And if not cured, what’s the consensus on the impact on longer periods of survival?

Dr. Brody: Doctors, especially academic doctors, are extremely diplomatic. We say to patients all the time that follicular lymphoma is incurable. Nothing’s incurable. We just have not found the cure yet. It’s not the disease’s fault. It’s us. There’s nothing magical about the disease. We haven’t been smart enough over the past 40 years, but we’re getting close. When my grandpa’s sister had Hodgkin’s lymphoma in 1949, it was 100% incurable. Now it’s 85% curable and that wasn’t that long ago.

We refer to follicular lymphoma as incurable. That’s how we write it in all of the papers. That sounds scary. It’s a terrible word. Whenever I say that, I have to say it’s incurable, like high blood pressure or diabetes. We don’t have a cure for high blood pressure, but we’ve got pretty good pills that can keep your blood pressure good for the next 50 years. We can’t give you one pill to cure it and that’s what we say for follicular lymphoma so far.

Bispecific antibodies have been the highest bang for the buck in follicular lymphoma in terms of efficacy versus toxicity. By themselves, they have some limitations. They’re good but not perfect. But in combination with standard therapies, like rituximab and lenalidomide, the complete remission rates have been huge in the first early studies. The big studies are getting done now.

Quite honestly, I wouldn’t be surprised if we look back in 20 years and find out that those who got bispecific antibodies plus combination standard therapies never relapsed. It will not hold for 100% of the patients, but it will be for a fraction. I don’t know that that will happen, but I absolutely would not be surprised because so many people are getting such deep remissions. We may be handing out curative therapies to people on those studies today. What’s the likelihood? Ask me again in 20 years, but it’s a real likelihood.

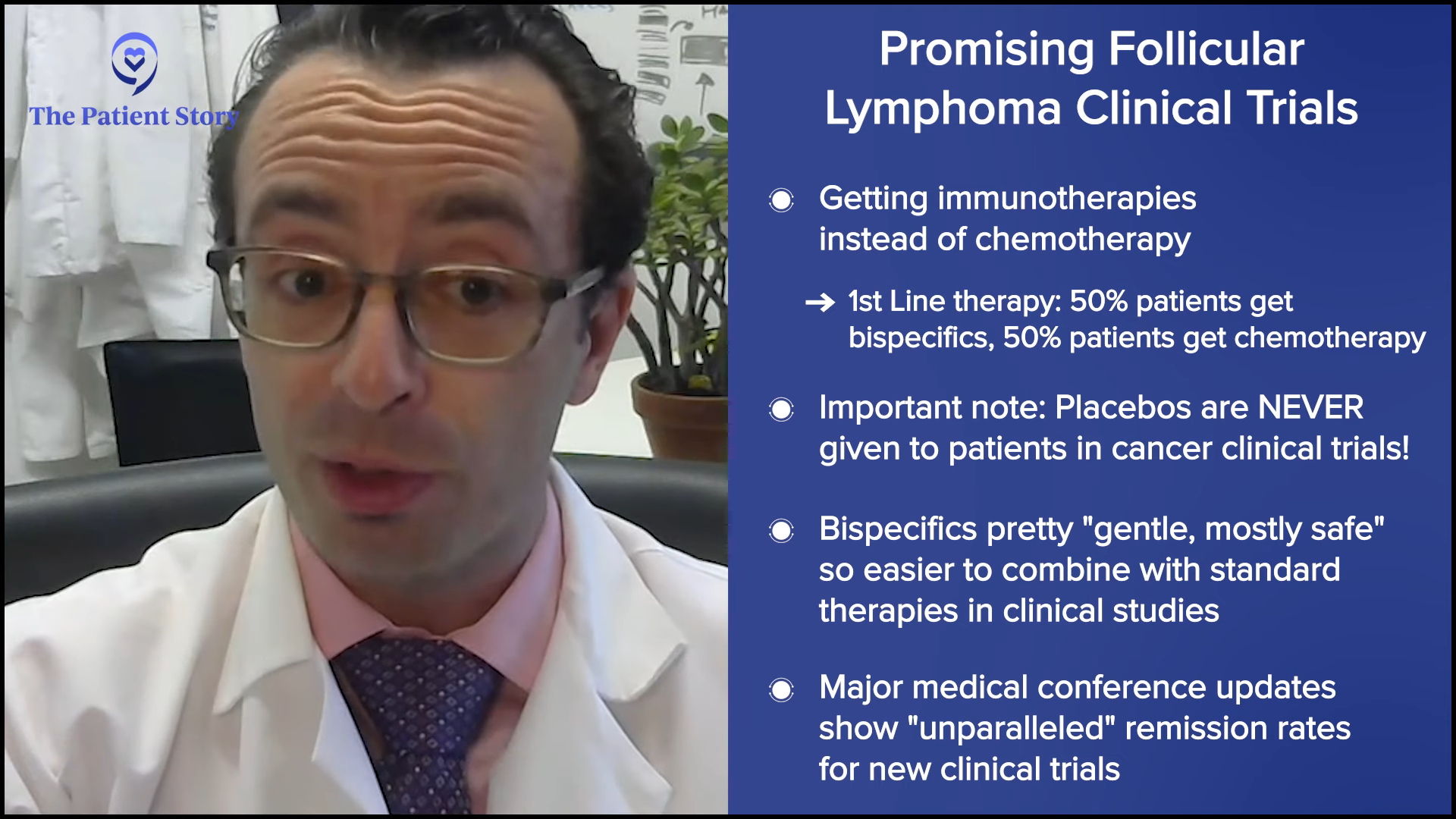

Clinical Trials in Follicular Lymphoma

Stephanie: When it comes to clinical trials, are there ones that are particularly exciting in the follicular lymphoma space?

Dr. Brody: Clinical trials are not always great. However, clinical trials are a time machine into the future. We have been giving people some of these bispecific antibodies in combination for about four or five years now, and some of them are just getting FDA-approved now. Some of these combination therapies are not FDA-approved yet, but they will be FDA-approved in the next year or in some cases, the next five years.

It’s a bit of a tragedy that Americans don’t get access to these mostly for lack of awareness. They’re available at many dozens or sometimes hundreds of hospitals around America, but maybe they didn’t think to ask or the person they asked wasn’t aware of them. That’s where resources like The Patient Story, The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, and the Lymphoma Research Foundation can be helpful in guiding patients. There’s no absolute commitment to be part of a trial, but hear about it and get the information.

We were talking about front-line therapies for follicular lymphoma before and then hinting at later lines. The NCCN Guidelines are clear. They recommend finding out about clinical trials. Old therapies are considered non-curative, but it doesn’t mean we can’t get a curative therapy with some of these promising trials.

The first thing that patients need at the beginning of their journey is the awareness that there may be some self-advocacy involved. No doctor in America should ever be annoyed if a patient goes and gets a second opinion. My patients get second and third opinions beyond me and I always ask because I’m always interested to hear what they say.

People think of trials as a last-ditch effort and it’s such a bad branding. It shouldn’t be. We have trials for front-line therapy and second-line therapy. The trials for first-line therapy are what we’re super excited about. One example is getting immunotherapy instead of chemotherapy. We have trials of front-line therapy of bispecific antibodies where half the patients get that and half the patients get standard therapy.

Patients have concerns that they’re guinea pigs and don’t know what they’re getting or they’re getting a placebo. There’s no such thing as a placebo in cancer clinical trials. They may get the standard treatment plus a placebo. In most trials, people are aware of what they’re getting. There’s no mystery.

Some of the most exciting trials give patients the chance to skip chemotherapy, to get front-line bispecific antibodies, and combinations of the standard with or without the bispecific on top of it. Because bispecific antibodies have been pretty gentle and mostly safe, we can safely combine them with standard therapies.

The results from some of the early versions of those trials that have been presented at ASCO and ASH showed unparalleled remission rates. They’ve been awesome. Some of those front-line and even second-line trials of similar combinations are, for me, some of the most exciting trials out there right now.

Dr. Bello: I agree. For bispecific antibodies or immunotherapy treatments, the trials that are moving them up now to the second line and even to the front line are the most interesting. If you could get a non-chemotherapy approach, that would be great.

Again, we always have to be careful because when we find out years later that this drug caused this kind of malignancy or this kind of immunologic problem, maybe we should have stuck with the original treatment that we had. Immunotherapies are the wave of the future and the sooner we can move them up, the better, and those are the trials that I’m looking for the results in.

Dr. Brody: In many ways, it’s a rehashing of 20 years ago. Rituximab was approved as a monotherapy and now, we say that rituximab is like chocolate chips: add it on top of everything. There’s not a single B-cell lymphoma where you don’t add rituximab on top of whatever the standard was before and made it better.

CHOP was the standard of care then, but no one talks about CHOP anymore. R-CHOP is the only thing now except for some newer versions of R-CHOP as well. I do think that that will be the standard five years from now. Wait five years for the better stuff or get access to it now through clinical trials.

Recommended Online Resources

Stephanie: A follicular lymphoma patient, Donna P., said, “One of my first questions was how long will I live. Until I found a support group, I was so depressed and fanatical about my disease. Then I started seeing all the comments and how longevity was in my diagnosis, so many others then gave me hope.”

In the initial conversations with the patients when they’re dealing with so much, do you have any guidance for them, whether it’s support groups or resources?

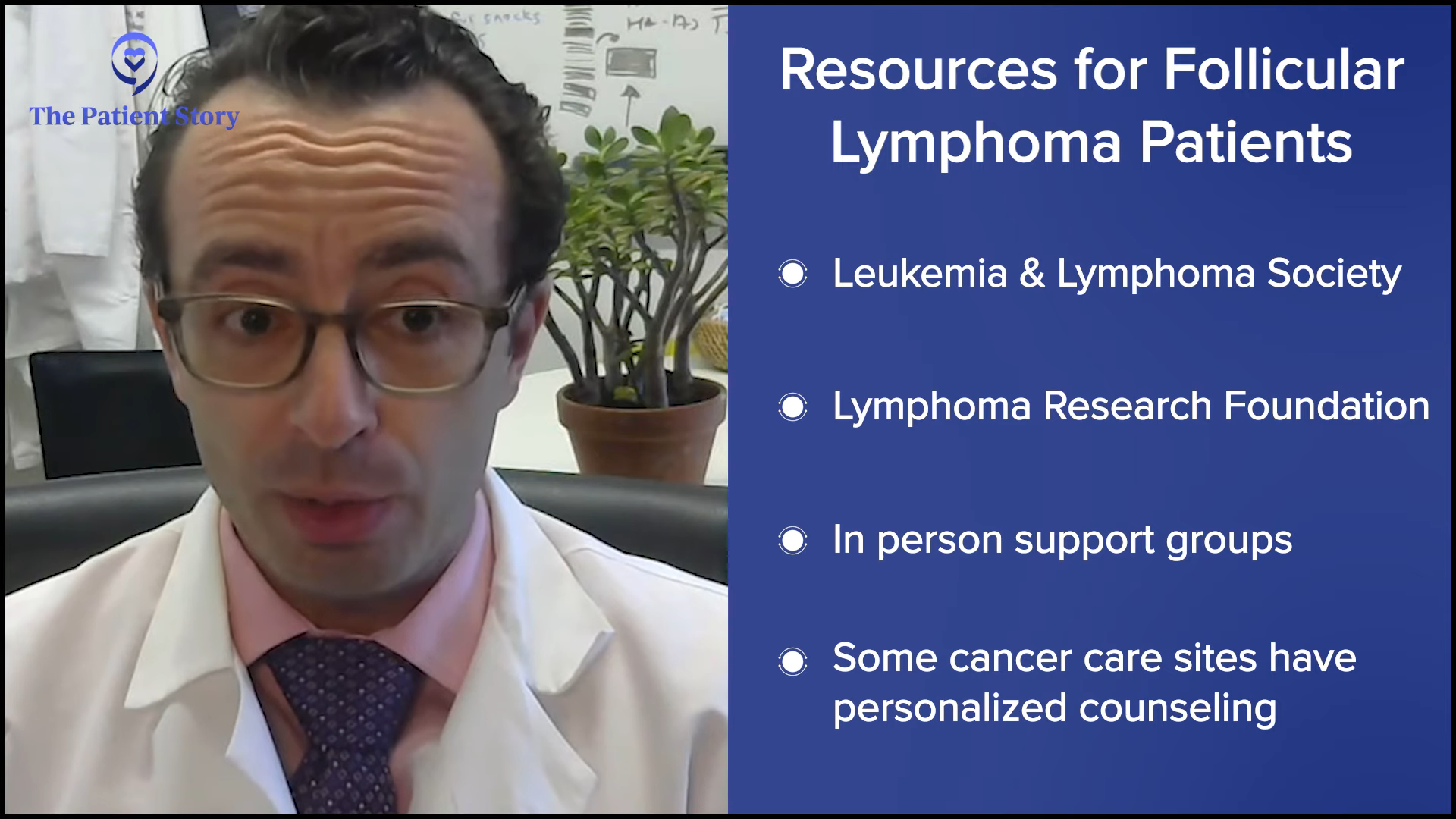

Dr. Bello: We usually give them a booklet from the American Cancer Society that has a summary of the different types of non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas, but everybody nowadays runs to Google. I tell them, “Don’t do Google.” If you want to go to some websites, I usually recommend The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society and the Lymphoma Research Foundation. Both of them have very good patient information.

Dr. Brody: My first recommendation always is The Patient Story and as Dr. Bello said, The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society (LLS) or Lymphoma Research Foundation (LRF). There are a few others as well, but those are the best for lymphoma patients.

We also sometimes have in-person groups. The stress of this can be a significant factor, especially for someone who already had stress as a problem before or anxiety as a diagnosis before, so we try to get them personalized counseling. At cancer centers, we’re very lucky to have counselors who have experience with cancer patients specifically or, in our case, with lymphoma specifically.

The LLS Clinical Trial Support Center

Stephanie: The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society has a Clinical Trial Support Center that offers free, one-on-one support. You get connected to an LLS Clinical Trial Nurse Navigator to help you throughout the clinical trial process from finding the right trial all the way through when you’re on a trial, making sure that you have all your questions answered.

Clinical trials aren’t a last resort. The terminology itself can be quite daunting. Patients need to understand more about what clinical trials are so that they can decide for themselves with their healthcare team. ClinicalTrials.gov isn’t necessarily the easiest site to navigate, but the Clinical Trial Support Center can help you navigate a resource like that.

The Right Time to Seek Lymphoma Specialists

Dylan: People often ask, “When’s the right time to get a second opinion?” If you or your loved one has follicular lymphoma, when is the time to get an opinion from a lymphoma specialist? Can you explain the difference between a lymphoma specialist and a hematologist-oncologist?

Dr. Brody: Let me first say that being a community oncologist is tough. Most of these folks are taking care of lung cancer, breast cancer, kidney cancer, bladder cancer, etc. It goes on literally all day. I’m buddies with dozens of them and I hear about what they do and how they stay on top of everything. It’s a very tough job.

Academic oncologists and community oncologists have a pretty good way of working together, which hopefully means they have my cell phone, and for any little thing, they’ll give me a buzz or give me a text. For most of those, the patient doesn’t need to come see us.

Compared to breast cancer, follicular lymphoma is rare. Your regular community oncologist knows about follicular lymphoma and has had a few patients with it. Every month, they see dozens and dozens of breast cancer and lung cancer patients, but probably zero follicular lymphoma. They’ll see maybe a few per year, so it would be impossible for them to stay on top of every little bit of data. There’s no way they could do that for every single type of cancer. Dr. Bello and I can barely do it for all the types of lymphoma, so you can imagine that plus other cancers.

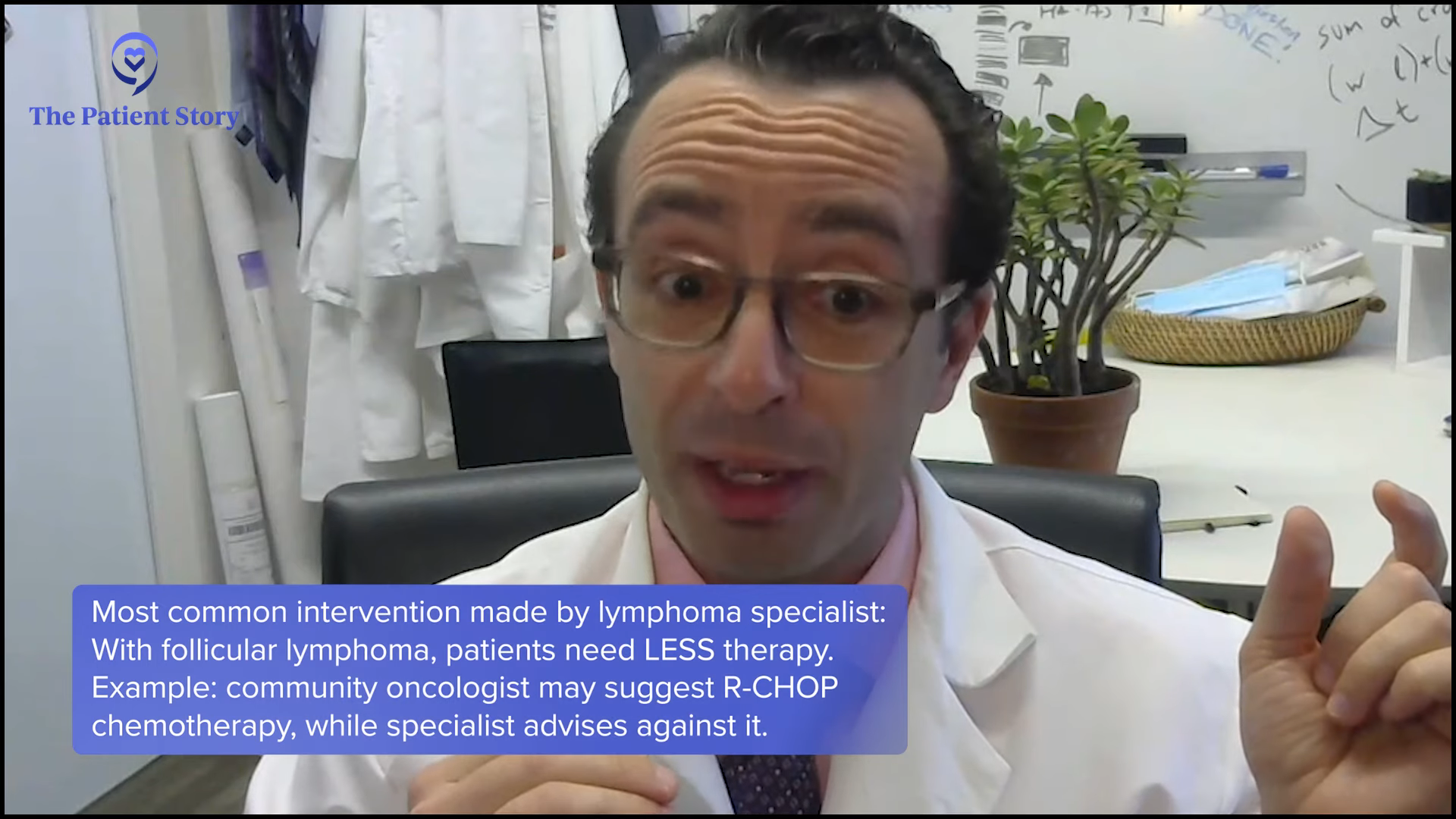

The answer for when to see a specialist is always. However, most patients don’t need to keep seeing a specialist. They can have a back-and-forth where we share the patients. The most common intervention I make when there’s a difference in opinion between me and the community oncologist is to downgrade the therapy. They’ll come in and say, “My community oncologist said I need R-CHOP,” and I’ll say, “You don’t. You definitely do not.” They can get either nothing and undergo active surveillance or get something gentle. We make them aware of clinical trials where they may get access to something that won’t be available for years sometimes.

I don’t fault them for saying that. Even a hematology-focused oncologist sees acute myeloid leukemia (AML), myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), myelofibrosis, and myeloma most of the day, and then a little bit of follicular lymphoma. As a lymphoma specialist, all we see is lymphoma, so we have to have a little more experience.

Final Takeaways

Stephanie: We’ve had an incredible discussion. Hopefully, many things have resonated, but if there’s one thing that you hope people would walk with, what would you like that to be?

Dr. Bello: One of the most important things is that it’s okay to not get treatment. There are a lot of times when people don’t need to have their lymphoma treated because a lot of low-grade follicular lymphomas can be observed. If that’s your doctor’s recommendation, come to terms with that and know that you’re being monitored. If something changes or happens, we have great options.

Lymphomas are very different than solid tumor cancers in that they all need to be treated and the sooner the better. You have to change your whole mindset with these kinds of conditions.

Dr. Brody: Dr. Bello said it beautifully and I agree with how she said it. If you get diagnosed with follicular lymphoma, thank God you got follicular lymphoma and not some horrible lymphoma because it could have been something else. Thank God you got lymphoma in the 2020s and not in the 1990s because the advances have been unparalleled. There’s no cancer where the advances have been as incredible as in lymphomas and B-cell lymphomas, like follicular lymphoma especially. I guarantee that the 2030s medicines will be better than the 2020s medicines, so some patients will be savvy enough to get access to those even now.

Conclusion

Stephanie: Thank you, Dr. Brody, Dr. Bello, and Dylan for this discussion. I really appreciate your time.

I hope that you enjoyed the discussion and we hope to see you in a future program. Take good care.

Thank you to Blood Cancer United for their continued partnership.

Follicular Lymphoma Patient Stories

Laura C., Follicular Lymphoma, Stage 4 (Metastatic), Grade 1 to 2; Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma

Symptoms: Incidental finding after hysterectomy (follicular lymphoma), thyroid nodule detected on imaging (papillary thyroid carcinoma)

Treatments: Immunotherapy (rituximab and lenalidomide or R² regimen), surgery (thyroidectomy)

Hayley H., Follicular Lymphoma, Stage 3B

Symptoms: Intermittent feeling of pressure above clavicle, appearance of lumps on the neck, mild wheeze when breathing and seated in a certain position

Treatments: Surgery, chemotherapy

Laurie A., Follicular Lymphoma, Stage 4 (Metastatic)

Symptoms: Frequent sinus infections, dry right eye, fatigue, lump in abdomen

Treatments: Chemotherapy, targeted therapy, radioimmunotherapy

Courtney L., Follicular Lymphoma, Stage 3B

Symptoms: Intermittent back pain, sinus issues, hearing loss, swollen lymph node in neck, difficulty breathing

Treatment: Chemotherapy