The Patient Exchange: Improving Clinical Trial Diversity

Edited by: Katrina Villareal

Take part in a transformative conversation with six Black patients as they share their journeys navigating clinical trials. This program tackles cultural and social barriers head-on, offering insights on starting discussions with your doctor, understanding enrollment, and overcoming mistrust and misinformation. Learn why cancer clinical trials are not so much about placebos but about “getting tomorrow’s medicine today” and gain the knowledge to make informed decisions for your health.

Know how to bring up clinical trials with your doctor. Understand the screening and enrollment process. Listen to real patients discuss their clinical trial experiences. Help dispel the myth of placebos in cancer clinical trials. Overcome mistrust, lack of info, and other traditional cultural barriers.

This great conversation is a true discussion where we can talk about barriers in the African American and Black community and the hesitation that some of us often feel when we want to go on a clinical trial.

Tiffany Drummond

Introduction

Tiffany Drummond: I’m a patient advocate with over 20 years of experience in cancer research. My journey as a care partner began when my mother was diagnosed with endometrial cancer in 2014. I quickly realized the challenges of finding reliable information to support her care, so I am committed to helping others avoid similar difficulties.

At The Patient Story, we create programs to help you figure out what comes next. Think of us as your go-to guide for navigating not only the cancer journey but your overall health journey. From diagnosis to treatment, we have you covered with real-life patient stories and educational programs with subject matter experts and inspirational patient advocates and guests. I truly am your personal cheerleader here to help you and your loved ones best communicate with your healthcare team as you go from diagnosis through treatment and survivorship.

Before we get to our speakers, we want to thank all of our promotional partners for their support, allowing our programs to reach the audience who needs them. I hope you’ll find this program helpful, but please keep in mind that the information provided is not a substitute for medical advice.

You may be wondering: what exactly is diversity in clinical research and why is this so important? Diversity in and of itself is vast in terms of what it means in specific settings. We’re going to focus on the experiences of Black patients. For instance, when we look at cancer and chronic conditions that increase the risk of developing cancer, Black people, who make up 14% of the US population, have a higher incidence and mortality rate.

Research is going to be paramount in understanding and eliminating this disparity, yet only 5 to 7% of Black patients are clinical trial participants. The panel you’re about to meet is representative of those who go on clinical trials. The conversation is going to be one that I hope resonates with everyone within and outside the Black and African-American community to help move research and development forward and be made accessible to all.

This great conversation is a true discussion where we can talk about barriers in the African American and Black community and the hesitation that some of us often feel when we want to go on a clinical trial. This conversation is going to resonate with us, especially in the Black and African American community because we don’t often talk about it, except when we’re thinking about the mistrust and other things that we’re going to get into throughout this conversation.

I had a bad taste in my mouth about clinical trials because my dad joined them and they didn’t work for him.

Gwen

I have with me current and former clinical trial participants, incredible panelists, and patient advocates. I also have with me Tony Williams, who is with The Patient Story as our head of diversity and inclusion and also a diffuse large B-cell lymphoma survivor. We also have Gwendolyn, a cervical cancer survivor, and Shyreece, a non-small cell lung cancer survivor. Because not all clinical trials are cancer-based, I have LaTisha, Latasha, and Cayla who were on clinical trials or at least screened for clinical trials for uterine fibroids, a chronic condition.

Clinical Trials Knowledge

Tiffany: If you’re familiar with The Patient Story, often we talk about the medical aspect of the patient story and experience, but what I want to talk about is getting to the point of clinical trials.

Cayla, how did you first learn about clinical trials? Was it through a healthcare provider or were you already well-versed in this space? What was that experience like for you?

Cayla: My mom was diagnosed with uterine fibroids and she learned from her gynecologist about a clinical trial that was going on. I didn’t even know I had fibroids. I was diagnosed at the trial and followed up with my healthcare provider, so it opened my eyes to my diagnosis.

Tiffany: Tony, what about you? Were you familiar with clinical trials before you started this journey?

Tony Williams: I’ve always been familiar with clinical trials, stemming back to the Tuskegee experiment and Henrietta Lacks.

When I was diagnosed in 2021 with stage 4 DLBCL, my front-line treatment was R-CHOP, which wasn’t as successful as we needed it to be so I relapsed. At the time, CAR T-cell therapy was being developed, but it wasn’t available for my type of cancer, so I waited about 4 or 5 months before CAR T-cell therapy became available for me. Participating in that clinical trial was a giving back and a next stage for me. My first and second line of treatments failed and that’s how I fell into it.

Tiffany: Shyreece, what about you? Were you always familiar with clinical trials or was this something that happened when you started your cancer journey?

Shyreece: I was ignorant about what cancer was and what clinical trials were. It wasn’t my world when I was first diagnosed in 2014, but I’m happy to be living now for over 10 years with active cancer.

I first heard about the clinical trial through a team of doctors when I was initially diagnosed. One oncologist said you need resources to have clinical trials in your local clinic. She didn’t have access to it. I needed to accept my diagnosis and the intravenous chemo that was given to me. I stayed one month with her and then decided to get a second opinion from the University of Michigan, where I had more options.

I moved to California and in 2022 at Stanford University, I had no idea that the mutations from the targeted therapy would no longer respond to any treatment, so they started popping up and growing. My doctor, whom I greatly respect and trust, said for two years that he looked out for a trial for me. They worked to get it to their hospital so that I could try it. I’m currently on it and I’m doing well. The tumors are disappearing. I’m excited to look at possibly another 10 years of living with a deadly cancer.

Tiffany: That is a perfect story to share because you went from not knowing what a clinical trial was to knowing medical terms and things that you didn’t know before, and that is inspirational at best. Gwen, did you know what a clinical trial was? How did this come into your purview?

Gwen: My father was diagnosed with lung cancer. I had a bad taste in my mouth about clinical trials because my dad joined them and they didn’t work for him.

Going into any treatment, you’re always going to have apprehension, but it’s the next step and you’ve come this far. Participating in a trial was a no-brainer for me.

Tony Williams

Clinical Trial Screening Process

Tiffany: Tony, can you share your experience about the screening process itself? Was it stressful for you? Did you feel supported?

Tony: My first two lines of treatments failed. Because I was at UNC Chapel Hill Medical Center, they offer a lot of different types of screenings and trials, so I was part of a university program that they were working on. UNC is a teaching hospital and because my oncologist was heading that up, it was easy for me to be screened. I didn’t have to go through anything. It was a matter of deciding if I wanted to participate. It was that easy.

You always have that anxiety because you never know. Whatever you’re participating in, you want to see the desired result at the end, which is to be made whole and healed. Going into any treatment, you’re always going to have apprehension, but it’s the next step and you’ve come this far. Participating in a trial was a no-brainer for me.

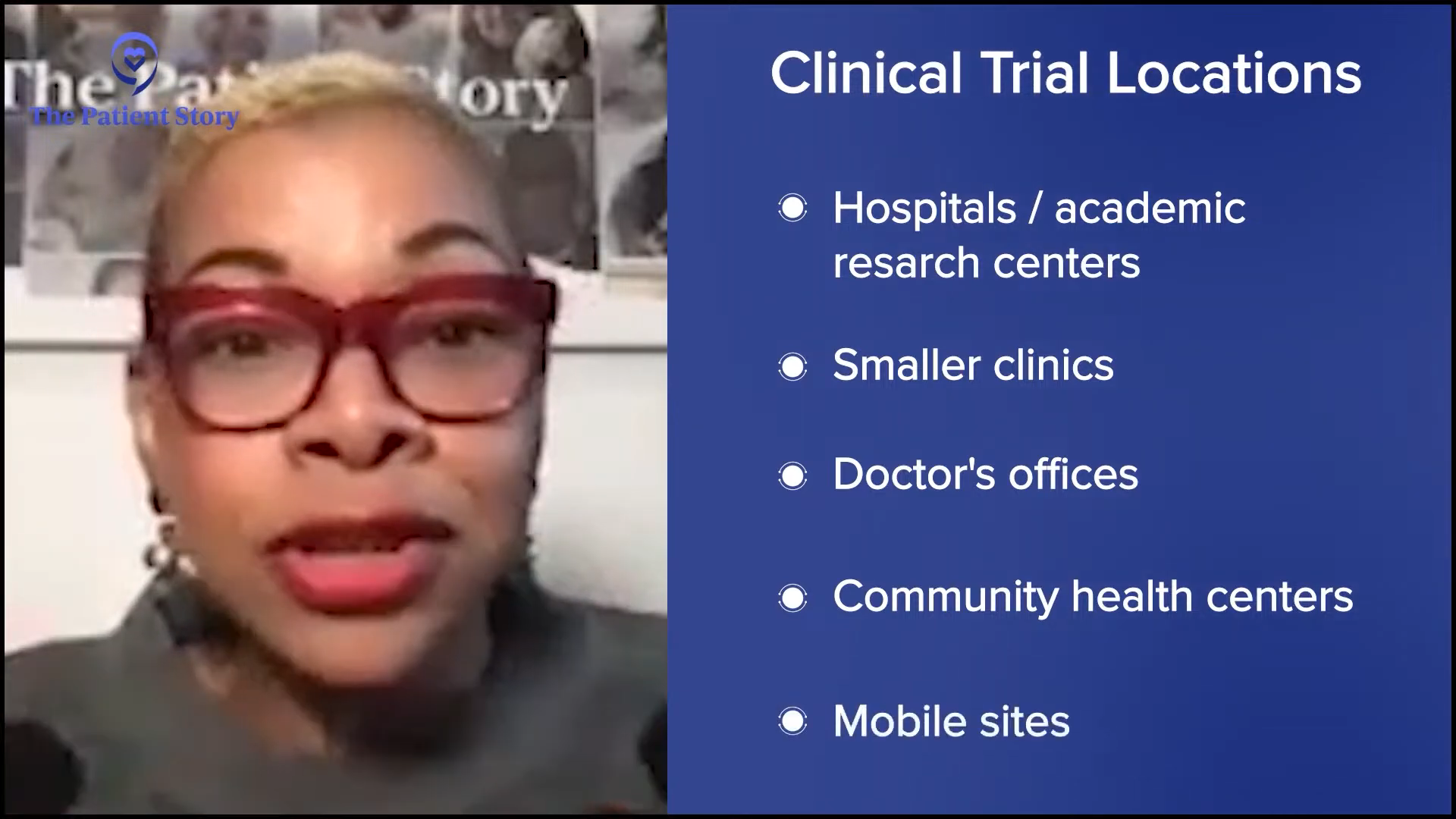

Tiffany: That brings up a point about where to go to access clinical trials. Oftentimes, it is going to be a large academic research center, but not everybody has access to that. There are local sites as well. We have to get that knowledge to the community about where these sites exist. Going to a larger research center like UNC, you will get comprehensive care.

LaTisha, when you were going through the screening process, did you have any hesitancy? More importantly, were there any barriers for you, like with transportation? Did you have to travel far? What was the experience like for you?

LaTisha: I’m in the hospitality industry, so it was hard to sync my schedule. I had to wait a little longer than anticipated to go to my first appointment to get the initial information on everything I needed to do, so that was pretty hard. It was around 15 miles away and I don’t drive, so those were barriers for me when I first started the screening process.

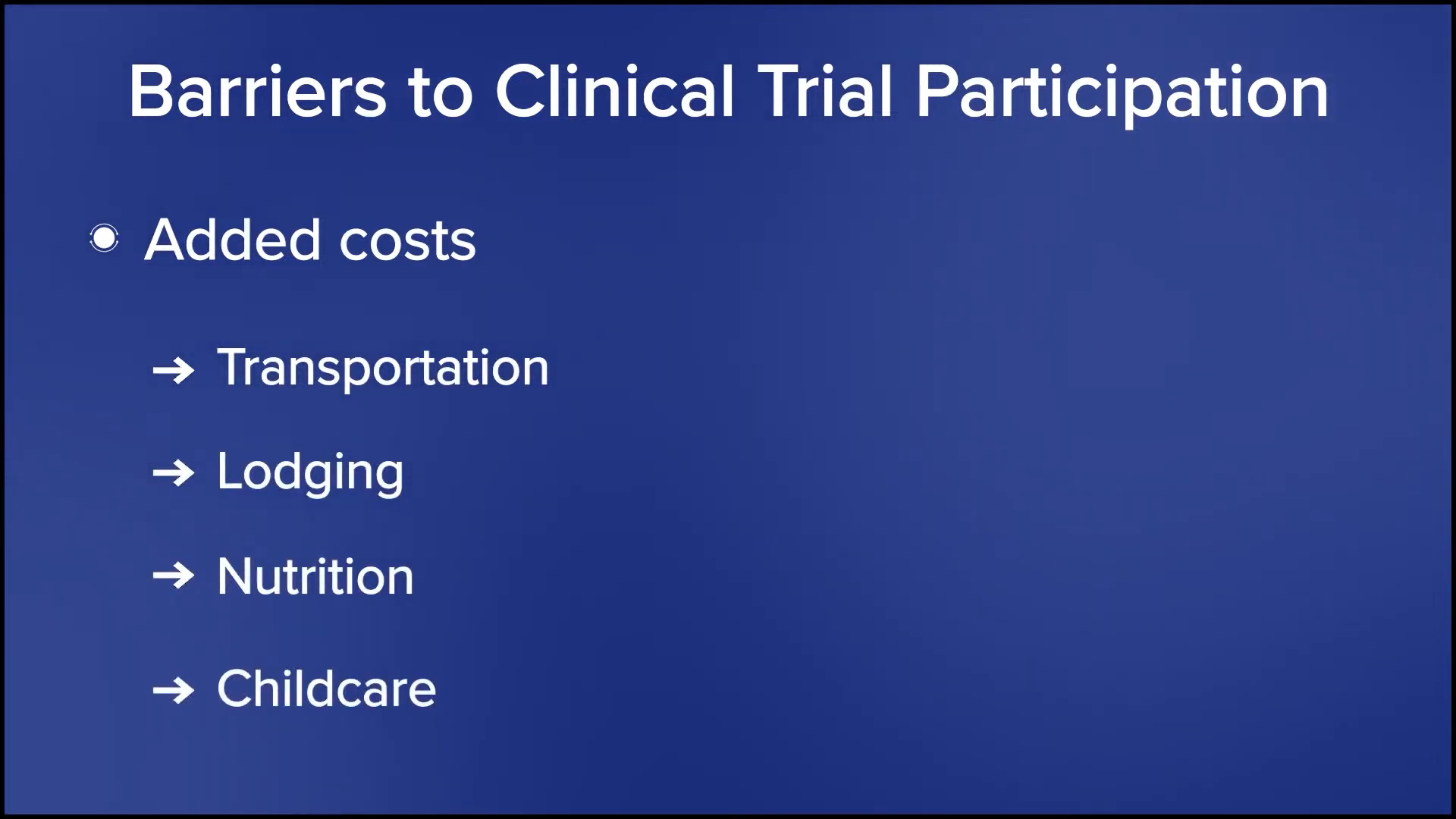

Tiffany: Thank you for being transparent. Those are barriers that exist and can prevent you from going on a clinical trial. Maybe you are eligible, but you can’t get there. With trials, you tend to have to go more often than you would for your standard care because it’s more comprehensive and they’re doing a lot of data collection. I know the medical community, especially the research community, is looking into how they can build in these added costs that affect participants’ ability to join the trial.

Receiving Treatment on a Clinical Trial

Tiffany: This conversation is specific to the Black and African American community participating in clinical trials, so hesitations and mistrust come into the intervention itself. For participants who received an investigational drug, starting with Shyreece, what can you tell me about the information you received when you were told about the clinical trial and what your treatment was going to be? Did you feel like you were a test subject or guinea pig when they were giving you the information?

Shyreece: ALKOVE-1 is a clinical trial studying NVL-655 for patients with advanced ALK-positive non-small cell lung cancer, which I’ve had for over 10 years. For someone to come and tell me after fighting that long that they’ve got something for me is incredible.

My doctor said, “I’ve been watching your cancer. I’ve been watching you and getting to know you, so I think that this is good for you.” The doctor-patient trust was already there because I trusted him along the journey through other things that he was doing. He said, “We’re going to counteract your cancer this way. We’re going to try this, slow it down, but the resistant mutations are always going to pop up, but I got something for you. We’re going to wait.”

He was trying to get his clinic ready to receive all of the resources needed to accommodate me in that trial as much as they could. I asked about transportation and all those barriers because I would have to go every week. It was an investigational drug, but I’m a power horse, so if there’s hope attached to it, then I’m going to try it. I’m not influenced by culture. I’m influenced by my trust in God and my doctor.

I can’t speak for everybody. If you don’t have that connection and trust with your doctor, I say find another one. I had no problem with going into the NVL-655 clinical trial because it was fully explained to me. I knew what the risks were. They sent the information to me by email and I had a month before I signed the consent form. I was very well informed and I knew that he was waiting on that trial for me. When the study coordinator gave me her cell phone number, I knew I was going to be in good hands.

It was an investigational drug, but I’m a power horse, so if there’s hope attached to it, then I’m going to try it.

Shyreece

Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trials

Tiffany: Here’s the question that’s going to need some unpacking, especially in the Black and African American community. When it comes to treatment, we don’t understand placebo, especially when it comes to cancer and chronic conditions. Before I get into that, to clarify, what are your thoughts on placebo-controlled clinical trials?

Gwen: After someone tells you that you have 15 months to live, you’re at the point where you accept whatever you can do to stay alive and to see your grandchildren grow up. You’re going to do whatever you have to do. I knew I had some more living to do. She said, “You have to trust the team. You have to trust God first and then you have to trust the medical team,” and I trusted MD Anderson.

I met my doctor at a retreat by a cervical cancer organization called Cervivor. She was a doctor at MD Anderson and I was going to another hospital at the time. I used to be a case manager, but I was having so many issues as a case manager that I needed a case manager.

At the retreat, I was crying to her. I said, “They don’t care about Black women. They don’t care about the women in my community.” She looked at me and said, “I care. Call me when you get back.” She has been true to her word. I reached out to her and said, “I need to know some things about clinical trials.” Her team reached out to me. It’s all about trust.

Tiffany: What often happens is when you go on a clinical trial, you get more comprehensive care. They want to know if the study drug or new combination is working for you. Maybe it doesn’t, but it may work for the next person. These experiences are what this program is about because when it comes to clinical trials, we don’t often get to see that experience. We only get to read about it or hear about the bad things that happen. Cayla, do you have any thoughts on placebo-controlled clinical trials?

Please note that the use of placebos in cancer clinical trials is very uncommon. In nearly every case, cancer clinical trials compare a new treatment or combination of therapies to the existing standard of care, rather than a placebo.

The Patient Story

Cayla: Automatically, you go in and say, “I’m going to try this and I’m going to be healed.” That’s the positive aspect, but not everyone is getting the medication. You don’t understand that a placebo has to be in effect. Try to do as much research as you can and reach out to the staff or someone you have a rapport with on the team. They can’t tell you if you’re getting a placebo because you might drop out. You should go in there knowing that you might receive the placebo and the next person next to you might receive the medication. Who knows? The person may receive the treatment and yet not have it work for them.

For anyone on a clinical trial, you will never not get anything. That is unethical. If you go on a clinical trial, you are at least going to get the standard of care for your condition.

Tiffany Drummond

It’s all about research and trying to understand as much as you can. There’s a lot of information out there and it discourages everyone from trying to be a part of the trials. People use verbiage that a lot of the people in the community don’t understand. Instead of explaining in-depth, the staff members look at us wondering why we don’t know. I’m a little 50-50 with the placebo. I’m proud of the trial, but I understand why the placebo is needed.

Tiffany: I’m glad you said that. This is what I always drive home. For anyone on a clinical trial, you will never not get anything. That is unethical. If you go on a clinical trial, you are at least going to get the standard of care for your condition. You’re never not going to get that.

What may happen is they give you the standard treatment in addition to whatever investigational drug they’re researching or a placebo. Oftentimes in our community, we think that they’re not giving us anything. This is the last resort, so we’re getting a placebo. This isn’t true.

You can ask. If you’re going into an office and they’re offering you a clinical trial, ask, “What’s the minimum I’m going to get? Am I going to get treated for my condition?” No matter what it is, whether it’s a headache or diabetes. “What is my alternative?” They should tell you in the consenting process what your alternatives are and the options that you’re going to be getting on the trial.

I didn’t want to have surgery. I wanted the bleeding to slow down or stop. That was what I was going to the trial for.

LaTisha

Measuring Expectations on a Clinical Trial

Tiffany: LaTisha, when you went on the clinical trial, what were your expectations? What were your thoughts on what you wanted to happen? Were you realistic about whether or not it will work?

LaTisha: I wanted to be more informed. I knew I had had fibroids for a long time. I was trying to figure out what my other options were. I didn’t want to do the surgery at all, so this would have been an option to not have surgery. However, they didn’t have the resources to see where my fibroids were, so she wasn’t able to see exactly where they were. I didn’t know they could be in multiple places. I didn’t want to have surgery. I wanted the bleeding to slow down or stop. That was what I was going to the trial for. I did not want to have the surgery at all.

Tiffany: Did you enroll or were you considered a screening failure?

LaTisha: I was enrolled. I had to do samples. They kept trying to do the ultrasound. They would tell me to come at different times of the month, but she could only do the vaginal ultrasound. She couldn’t send me for an MRI or anything that wasn’t part of the screening process. I probably went for about three months. When they couldn’t get the imaging that they needed to get, then that’s when I had to stop.

Tiffany: What about you, Latasha? Are you still on a clinical trial or are you done? Would you consider going on another one?

Latasha: I’m at the beginning of a clinical trial. When I started my endometriosis journey a couple of years ago, my fibroids were small. Then it got to a point where they started to bother me so much and I was hurting, so I had them removed.

I didn’t want to have surgery either, but when they say they need to remove something that’s not supposed to be there, I’m all for it. It gives me a better chance to regroup and allows the researchers to see how fast the tissue is growing or how much the lining of the uterus is accumulating each month. They’re able to start tracking what they couldn’t see before the fibroids started growing or the uterus started thickening. It’s hard to go by what everybody else says because they have some good points about the placebo.

Side Effects on Clinical Trials

Tiffany: Oftentimes, we’re afraid of the unknown and when I say we, I’m talking about the Black and African American community and with valid reasons. Tony, when you were on a clinical trial, did you experience any adverse effects? How did the side effects differ than when you were on standard therapy?

Tony: Anytime you’re diagnosed with cancer or any other disease, there’s a level of faith that you have to have and that will be activated during your journey. You’re going to believe in God, but you’re also going to believe in the medicine that God can work through.

Undergoing CAR T-cell therapy was terrible. I had a very aggressive chemotherapy regimen, but CAR T-cell therapy was worse because it was coming off a clinical trial and I was getting that as a second-line defense. The procedure that I had to go through was a lot of trauma to the body, with the extracting of my blood, taking it to a lab to get it re-engineered, and giving it back to me. I have received the worst chemotherapy that they have and that didn’t solve this, but I kept my faith knowing that at the end, I’m going to see this through.

One thing I never asked during my journey and until now was why. Why not me?

Tony Williams

When I did CAR T-cell therapy, that previous six-month period when I got chemo, they gave me that in three days. I felt like I was seeing death. Darkness came over me because it was so aggressive. My body was in shock. I recall the first day that happened, I was out of sorts. The second day, I passed the chapel and said, “I can’t do this,” but I knew I could and I did.

It was very hard, but one thing I never asked during my journey and until now was why. Why not me? Why can’t I be the one to help somebody get through this? I made it through the chemo on CAR T-cell therapy, but it was unknown. I was afraid, even though I didn’t admit it.

You have to exist in a reality that’s not there for you but where you’re going to exist because if you exist in the right now, you will not get through it. You have to exist in a realm that’s beyond where you are. It was very challenging and tough. Not knowing if it was going to work was even more excruciating because you knew what you had already been through.

I never felt like a guinea pig. I felt like it was necessary. The way that drugs come to the market now is not like it was back in the time of Tuskegee or Henrietta Lacks. They have to do what they can to bring the drug to the market. When you join a clinical trial, like Tiffany said, you are getting the best of what they have because they want that to succeed. You are a frontline participant of the best of what they have.

It was traumatizing. It was excruciating and painful. Parts of me wanted to doubt, but when you’ve come this far, what do you have to lose? God has already proven that He’s with you. When they give you a ticking clock and say you have one to three years left and you passed that, what do you have to lose except to continue to believe? That was my mentality.

Tiffany: As a caregiver to someone who did not go on a clinical trial but knew about clinical trials, I understand that some of these drugs are toxic, whether they come to the market or not. Gwendolyn, when you go through that on a clinical trial, does it make you doubt? Am I doing the right thing or is it like Tony said, like you know it’s going to be hard, but you’re going to push through? What was your experience?

If you want to send somebody to talk about clinical trials, send me. I’m alive today first because of God, but second because of the clinical trials.

Gwen

Gwen: So much of what Tony said is so true. Radiation and chemo kicked my butt. I had every side effect on the list. I knew I was a fighter, but I was leaning against the ropes and I wasn’t standing anymore. I want to live.

I tried everything. When you’re fighting stage 4, all of your family and friends have the remedy. Everybody called me saying, “Eat right. Don’t eat meat. Juice. Do nothing but herbs.” I was everybody’s guinea pig. In the Black community, everybody has a remedy, so I said let’s go. If you’re stage 4, you’re already getting a beating, so let’s try something new.

The crazy part about it is when I tried clinical trials, they put me on steroids too because mine was in my bones, so I gained weight and got stronger. I tell people all the time that I’m a walking billboard now. I’m alive because of a clinical trial. If you want to send somebody to talk about clinical trials, send me. I’m alive today first because of God, but second because of the clinical trials. I was dying from radiation and chemo. I had three strokes and two heart attacks. I’m on team clinical trial. You can’t tell me anything different.

Tiffany: Experiencing side effects when you go on these trials isn’t talked about a lot, not realizing that you can have these same side effects with drugs that are on the market as well. Shyreece, I want to hear your experience as well. When you were going through your treatment on the clinical trial, did you ever reach a point when you thought about whether this was the right thing to do or you should think about going off? What was that like for you?

Shyreece: Muscle myalgia was big for me in the initial stage of my diagnosis. It was so bad that I had cramping and abdominal pain. I even got C. diff at one stage of my journey. It was so bad that on Christmas day, I had to go into the hospital for two weeks to be treated.

I love mustard greens. Thanksgiving was coming up and I cooked some ahead. I ate a couple of bowls and it tore me up. I had to lay down, cramped. Sometimes you have to change some of the natural things that you’ve been doing every year. The side effects can come out of the blue. You don’t even know when they’re going to hit you. I nurtured myself until I felt better. That’s how I roll when it comes to side effects.

I’m at a place where I stay surrendered. If I’m going to do the trials and treatments, I have to stay surrendered and resilient. I’ve always believed in God. I’ve always believed in Jesus. But when I got diagnosed with cancer, I thought, “What did I do wrong? Oh, I need to forgive somebody.”

When I went to Stanford, they issued an NCCN Distress Thermometer, a survey that assesses your well-being from week to week by the time you come into your clinical appointment to see where your psychological state of mind is at. Fighting cancer is as much mental as it is physical. How did a cough turn into stage 4 lung cancer? When I cough now and clear my throat, I say, “Wait a minute.” I’ll cough and then tell myself, “Self, don’t you over cough. Self, cough just enough. Self, get you some water.” I have to talk to myself like that. It may sound crazy, but it works for me.

I also tell myself that I was created. I had to read the Word for myself. I love everybody in my faith community, but I had to get deeper into finding a purpose as to why I’m still here. I’m not going anywhere until I have done everything that my Creator has prepared for me to do.

With that being said, I take that power and mental state of mind, get to know my team, and pray. What should I be doing? Who should I be doing it with and where? I’m at Stanford. The people who I’m working with are those particular people. I am present. I am all in. If and when I do decide whatever treatment I’m going to do, I don’t attach any cultural baggage to it because I know it comes from a place of fear and I can’t live in fear. I have to trust today. I have to trust God today and the people of today. If I don’t trust who I’m around, it’s not going to work anyway.

Tiffany: Cayla, LaTisha, and Latasha, for your clinical trials, what did they tell you was your intervention?

Cayla: They had to confirm that I had fibroids to be on the trial. They asked a set of questions to see if I qualify. I got to a certain point and they told me there was nothing they could do. They needed more resources.

An MRI confirms how big the fibroids are and their location. Fibroids can enlarge the uterus and it can be on the uterus, behind the uterus, and in different locations, so they weren’t too sure. They knew I had them, the size, and how many, but they didn’t know where they were. They told me to count how many sanitary napkins I was going through. I kept a log of how often I had to change and how often I had to take anything for pain management. They wanted to make sure before they gave an intervention.

You had to see them more. They had to collect samples. My intervention was to make sure I controlled it. With any disease, diet is important. Are you exercising? Are you a smoker? Do you drink alcohol? These have an effect. I would say they contributed to the intervention as well. I didn’t take medication to assist me. I did the non-pharmacological method.

Tiffany: What this shows is that when we say intervention, people automatically think it’s a drug and that’s not true. They could be collecting data. Oftentimes, what we don’t understand collectively as a community is that the data that we’re looking at is not representative of the people who it affects the most. With conditions that disproportionately affect Black and African Americans in high incidence and mortality, we’re never going to find an answer about why it’s happening if we don’t get data from the people it’s happening to.

Go to where we are. Use layman’s terms, simple language in a nice brochure, and put them in common places

Shyreece

Bridging the Clinical Trials Gap

Tiffany: You all have been passionate in your answers and that spreads more message than someone reading something that they don’t understand. These are shared experiences. What can we do to bridge the gap to make clinical trials less fearful?

Shyreece: We’re the ones who can best spread the message. Go to where we are. Use layman’s terms, simple language in a nice brochure, and put them in common places, like supermarkets, churches, and predominantly underserved schools, where the demographic is mostly Black. Leave some literature with visual representation so they can be easily read. Include information about the screening. Don’t be afraid to speak a little faith language to get on the inside and let them know that you care.

Tiffany: I believe that our life experience is our expertise and sharing that is going to make the difference. I talk about clinical research to anyone. If they’re listening, I want to promote it. These are things that we want to understand because we’re always asking why. Why us? Why are we always getting this? No one can ever give us an answer. The only way we’re going to get that is to look at data.

I believe that we as African American people have a lack of awareness overall about our health.

Tony Williams

Tony: What I have found over my travels with The Patient Story and being the head of diversity is to stress overall health awareness. When you go to the places that Shyreece mentions — our churches and civic centers, where we gather — cancer is not the one single modality. There is always something attached to it, like high blood pressure, high cholesterol, or diabetes.

I believe that we as African American people have a lack of awareness overall about our health. Cancer manifests itself, but something else is manifesting. If we can get to the root that, we take care of ourselves overall and you will not see the manifestation of a lot of these things.

Everything is tied to what you put into your body. Limit exposure to garbage. Overall awareness and pushing that initiative is the first place to start. Cancer is one of many. We all have that in common, but that’s not the only thing. We’re being taken out by heart attacks and other health issues too. Cancer didn’t have a chance to pop up because the heart attack got you first.

Tiffany: Usually, you’re seeing your primary care for everything and that’s the person who’s going to give you the workup that’s going to say something’s not right. How can we be more self-aware and advocate for ourselves to say, “Doc, what else is out there?” We know there will be barriers, like transportation, childcare, and having to leave work, which is a deal breaker for many people because they don’t have the means to do that.

I had to put myself out there and start a fundraiser… If I’m doing this and willing to do this, how can I encourage someone who may not have the skill set?

Shyreece

Shyreece: When I realized that, I had to put myself out there and start a fundraiser. It’s so humbling and so vulnerable, but I wanted to do it and I had to go first. I couldn’t wait for the reimbursement from the sponsor, so I had to put a plan together and execute the plan.

There’s so much preparation involved. If I’m doing this and willing to do this, how can I encourage someone who may not have the skill set? Let’s talk about that and be very transparent. Everybody may not have the skill set and the resources. How do you encourage them? Where can we have a list of resources? Where are these places to get support? How do you handle rejection? I powered through it. Everybody doesn’t have that support system. How do we encourage those things first?

I tell my story because this is my community and where I grew up. Start where you are.

Gwen

Gwen: Cervivor trains us. Even though I have cervical cancer, that doesn’t mean that I’m trained to speak to the community. Before I can do that, I have to know the facts and when I’m speaking, I have to give them the truth. I can’t talk off the top of my head.

Before I even knew I had cancer, I started a cancer organization in memory of my father. I go around the low-income Black and Hispanic communities. I go with MD Anderson now because now we have a relationship. I tell them to leave their white coats at home and be in jeans and tennis shoes. We want them to have a comfortable conversation where they’ll open up to you.

When I go out there, I bring in resources because I can’t go in there and tell you to get screening and not have help for you. I can’t leave you out there by yourself. We have to have more of that going on. We have to get out there.

I tell my story because this is my community and where I grew up. Start where you are. Cervivor told me that my story matters. They gave me confidence, so I’m out there now telling my story and we can have that conversation. I partner with schools, business owners, and churches. We need to go to the important places in the community.

Shyreece: Amen. I wrote my book for that reason. I started in my church. Start where you are.

Conclusion

Tiffany: I want to thank every single one of you. You all have made an impact in this conversation. I’ve learned about things that I did not know, so thank you so much for being willing to share with me and The Patient Story. Your experiences are going to resonate with a lot of people.

If you’re in medical school, you’re seeing the same stats that we’re seeing. You’re reading it, but we’re living it. You can understand better and get a bigger picture about why it’s so important that we participate in these clinical trials that can literally save lives.

What an electric and energizing conversation for sure. It doesn’t take much for me to talk about clinical research. Sharing the room with Tony, Gwendolyn, Shyreece, LaTisha, Cayla, and Latasha was icing on the cake. It is important to be empowered so that you and your caregivers can make informed decisions about your care.

Thanks again to our promotional partners.

Lung Cancer Patient Stories

Chris Draft

Background: Chris' wife Keasha passed away from stage 4 lung cancer one month after they married. He's been a passionate lung cancer advocate ever since.

Focus: Leading with love, making connections to grow lung cancer community, NFL liaison

Rhonda & Jeff Meckstroth

Background: Jeff was diagnosed with stage 4 lung cancer and given months to live, but his wife, Rhonda, fought for a specialist that led to biomarker testing and better treatment options

Focus: Education of biomarker testing for driver mutations, patient and caregiver self-advocacy

Terri C., Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, KRAS+, Stage 3A

Symptom: Respiratory problems

Treatments: Chemotherapy (cisplatin & pemetrexed), surgery (lobectomy), microwave ablation, radiation (SBRT)

Stephen H., Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, ALK+, Stage 4 (Metastatic)

Symptoms: Shortness of breath, jabbing pain while talking, wheezing at night

Treatments: Targeted therapy (alectinib), stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT)

Stephanie W., Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, ALK+, Stage 2B

Symptoms: Persistent cough, wheezing

Treatments: Surgery (bilobectomy), chemotherapy, targeted therapy