The Latest in Breast Cancer Patient Research

A conversation about the newest breakthrough, treatments and advocacy

The San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium (SABCS) provides the latest information in research, prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of breast cancer patient research.

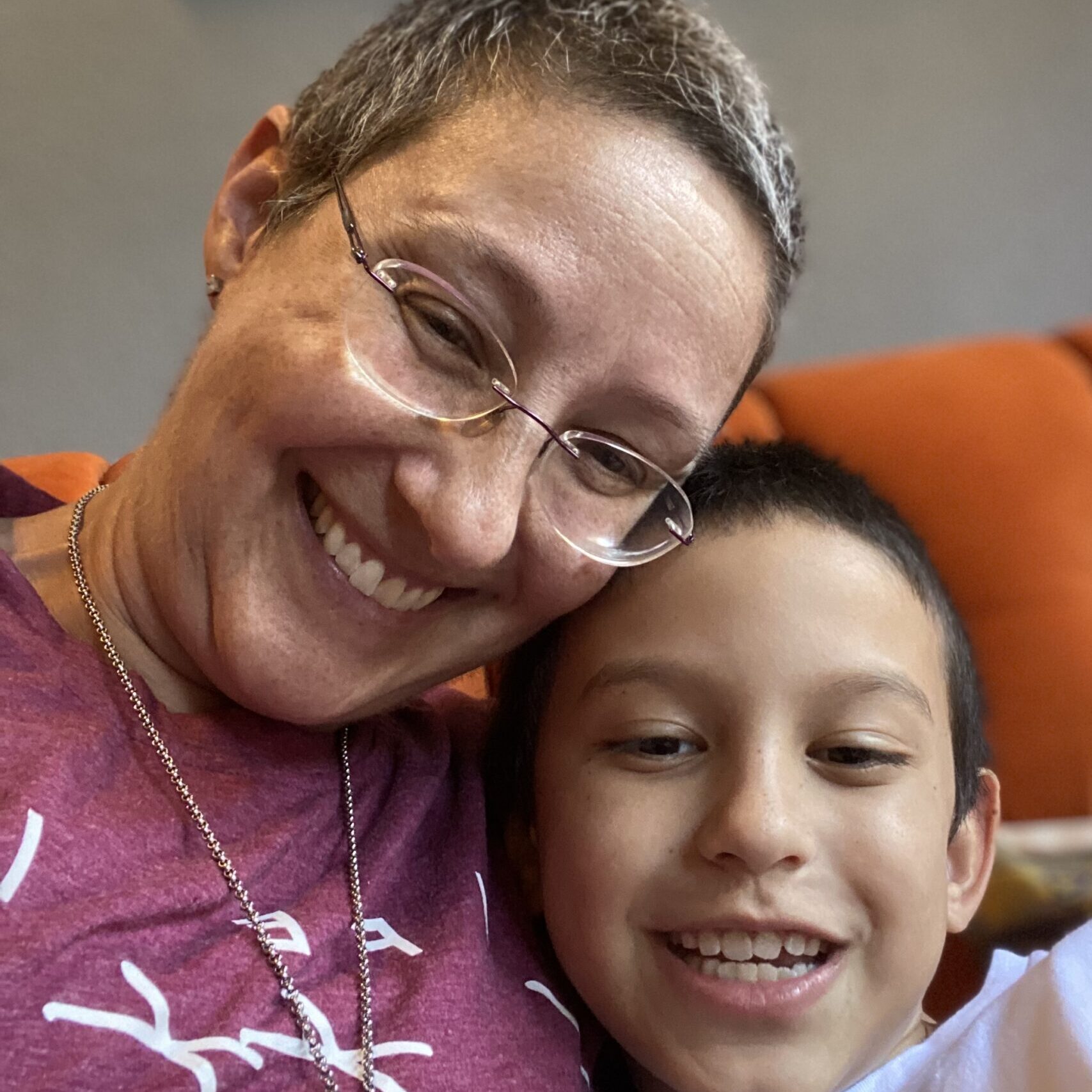

Lesley Glenn is a cancer patient advocate who was diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer over a decade ago.

Dr. Mya Roberson is a health services researcher, a health equity champion, and an assistant professor in the Department of Health Policy at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine

Lesley and Dr. Roberson sat down with The Patient Story to discuss patient research and news coming out of SABCS 2022.

This interview has been edited for clarity. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider for treatment decisions.

Introduction to Lesley

Lesley G.: Hi. My name is Lesley Glenn, and I have been living with metastatic breast cancer for a decade now. I want to tell you a quick story before we get into this really amazing interview with Dr. Mya Roberson from Vanderbilt.

I was diagnosed first with stage 2B. When I came out of the oncologist’s office at that time, I was loaded down with brochures, magazines, beanies, blankets, scented candles, and hand lotion. I had all of these resources handed to me for what I thought was going to be maybe an 8-month journey of going through treatment.

Soon after that, I went through scans, and they found hot spots in my body, which ended up being a metastatic disease to my bones. I was really stage 4 de novo, which means from the beginning. When I got that diagnosis, I walked out with a piece of paper that basically said, “You are stage 4, and you are 99.99% incurable,” and I had no resources. I had nothing. I had a piece of paper that said that I was incurable.

Shortly after that, I started IV systemic chemo, and it ended up being really toxic for me. I ended up with full-blown sepsis in the hospital for a month. After I was getting better from the sepsis, the oncologist came back to me, and she said, “Okay, are you ready to go back on chemo?”

My thought was, “Are you kidding me? This almost killed me, and now you want me to go back on this treatment that was actually worse than the cancer itself?” It took me to a place of really trying to pursue what I thought was missing in this whole dynamic of patient-doctor care.

As I started my advocacy journey, getting to know the scientific part of it, and talking to researchers, [the missing part] was where is the patient voice in all of this? Why doesn’t our voice matter? Why is everyone running through — I’ve heard the term used before — all of these shiny new toys that may be giving cancer patients, especially metastatic breast cancer patients, one month more without quality of life [being] taken into consideration?

Sure, we want to live longer. The statistic is that those of us with MBC only have 3.3 years. That is the statistic. I know that we’re not statistics, but at the same time, there are a lot of people that are still dying from metastatic breast cancer. We know that research is going into helping us to live longer, but we feel that our voice is so very important.

When I started my organization, Project Life, which deals with the survivorship and the thrivership of those of us that are living with MBC, it was really important to me that we be studied.

Why are there gatekeepers in these survivorship programs that are saying, “I’m sorry, honey, but this is not for you. You have to be done with treatment, and then you can come and join our programs”? My [thought[ was, “I’m never going to be done with treatment, and I deserve all of these extras just as much as those that are done with treatment.”

Introduction to Dr. Mya Roberson

Lesley G.: Fast-forward to 2020, when I was introduced to Dr. Mya Roberson from Vanderbilt University through a good friend of mine. She wanted to have the conversation about cancer care delivery with metastatic breast cancer patients and how it was very important. What do metastatic breast cancer patients care about? What do they need, what do they want, and what is the best type of support that we can offer them?

I’d like to introduce you to Dr. Mya Roberson. Dr. Roberson, can you share a little bit about your passion [and] how you came up with this project? Her passion for the cancer community is amazing.

Dr. Roberson: My name is Mya Roberson. I am an assistant professor of health policy at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine. I am interested in making sure that as we get better at treating cancer, our advances are making it to everyone and that everyone has a high quality of life through their cancer survivorship journey.

I became particularly passionate about metastatic breast cancer survivorship [from] hearing from patient advocates, starting as simply as on Twitter. [I was] hearing the patient voices highlighting the needs and the gaps that face this particular community around cancer survivorship.

[I was hearing] how most of the research that exists, when it does exist, around metastatic breast cancer focuses on end-of-life care, rather than understanding that there are individuals living with metastatic breast cancer and thinking about what the specific survivorship needs [are] for those individuals.

That was really the impetus for this partnership to work with an organization like Project Life, founded by my wonderful colleague and collaborator Lesley Glenn. [The impetus is] to really understand the patient-centered issues related to metastatic survivorship [and] to broaden the conversation, taking a step back well before we even get to conversations around end-of-life care. What does it look like to live well with metastatic cancer?

It’s really been my honor as a researcher to partner and amplify this work. An analogy that I really like to use for how I see myself as a researcher in this space is that the patients and the patient advocates have the microphone, and through my work, I grab the megaphone to really amplify the needs and what is most important to patients and patient advocates.

Lesley G.: It has been such an amazing experience to work with you, Dr. Roberson, this past year. We have just built this great collaboration. What has been most meaningful to my community at Project Life is that their voices are heard. It’s the first time that someone has ever taken the time to really listen. What is working for you, what is not working for you, and what do you need?

For so many years, the metastatic voice was not heard. We were put on the back shelf, and [told], “Well, you’re going to die anyways, so we don’t really need to be funding these types of things.” For someone like me that’s been living for 10 years with metastatic breast cancer, my quality of life is really very important to me, like the side effects.

I shared the story before about being really sick from chemo, then the oncologist trying to push me back to go back on chemo, and then me saying, “Wait a minute, but that made me feel horrible. I don’t want to feel horrible, so can we find something else for me to do so that I do not feel so bad? I still want to be able to function as a human being.”

What you have done for the community and making their voices known has been so pivotal for us. I know it’s just a precursor of getting our voices heard to get more research out there to really listen about our survivorship and what’s important to us: quality of life.

For those clinical researchers that are looking for new treatments to really think about, “Okay, well, they don’t want to be nauseated 24/7. Yes, they want to live longer, but they don’t want to be bedbound the whole time that they are living longer.”

Having this type of research gives the patient a voice. We’re able to share that with the clinician part or the scientific part of putting together new treatments. This is what the community is really wanting and needing. I feel very strongly that they’re going to start listening.

What is the impact of this type of breast cancer patient research?

Lesley G.: Dr. Roberson, what is the impact of this type of research for us that are living with metastatic breast cancer? What does it mean to the general public? People will be watching this and go, “I don’t know anything about breast cancer. No one has been affected.” Why is this type of research really important?

Dr. Roberson: I foundationally believe as a researcher and as a person that nobody knows cancer better than people living with cancer. That is, to me, the foundational importance of this work. It is, at a very fundamental level, elevating the voices of people living with metastatic breast cancer.

As part of this study, one of the questions that I asked all of the participants was, “How would you reimagine metastatic breast cancer care delivery in your own words?” I believe that the solutions are within the folks who live with these conditions day in and day out. It doesn’t necessarily have to be a top-down researcher or clinician’s approach. It really needs to be a patient-centered approach.

What I learned from asking that fundamental, foundational question was so insightful. I got answers like, “I wish I was connected to palliative care earlier. I wish that my oncology team could communicate with non-oncology specialists. I wish I had better mental health support to deal with the depression that I’m experiencing, being faced with a stage 4 cancer diagnosis.”

Those are all things that we should already foundationally be doing for people living with metastatic cancers broadly. What really struck me is the most quote-unquote out-of-the-box answer that I got to that question was, “I wish I could be poked less. I wish that I got prodded less when I went to my clinical care visits.”

Literally using the word “reimagine,” these are the things that folks come up with. [These are] the things that we already know that we should be doing and just need to be doing better. That’s my hope for this work and the work that it could potentially inspire.

We should be asking all folks living with cancer, metastatic and otherwise, even beyond just metastatic breast cancer, “How would you reimagine care delivery?” Your voices absolutely matter, and we as researchers should be listening and elevating those sorts of voices to ensure that we are doing things in a very patient-centered way.

What were you thinking and feeling during those conversations?

Dr. Roberson: On one hand, I felt very discouraged hearing some of these narratives of folks feeling not listened to. That, and thinking about my research colleagues writ large, that we are not centering patients in what we do. That’s what we should be doing as cancer researchers.

On one hand, it was discouraging in that way, but on the other hand, it was very inspiring because folks are so explicit about what they wanted to see done and what they wanted to see be done better. To close that out, it gives me a lot of hope that there are things that we can do. We have this great foundation of ideas of what patients would like to see be done better about the healthcare system.

It’s really that full range of emotions, honestly. [It’s] that idea of, ‘Oh my goodness, these things should be things that we’re doing. They should be simple.’ That’s where the discouragement comes in. But also, wow, how fortunate we are as researchers to have such a robust group of patient advocates broadly participating in our scientific conferences, participating in research, [and] giving us such great ideas to make our research even better.

What does success look like to you?

Dr. Roberson: To me, success looks like when patients or patient advocates come up to me, come up to Lesley, or come up to anyone else involved in this work and say, “I see myself in this research.” Whether or not they’re a direct participant or not, that they see themselves reflected in the kind of work that we are doing. This isn’t some kind of abstract idea. This is really, literally that patient-centered work.

That is a different metric of success than our traditional academic norms. As a researcher, I want to do work that matters to the folks that are most affected by these issues. That’s my metric of success. I don’t ever want to get to a point where someone asks me, “What is the application? What does this mean for patients?”

I want folks to be able to see [that] I see myself in this work. Quality of life is something that deeply matters to individuals living with metastatic cancers. My value of success is for folks to be able to see themselves centered in research.

I would even take it broader than that. I am a health policy researcher, and so my metric of success is being able to have those sorts of data, have those sorts of publications, [and] have those sorts of presentations that we can take to the Hill [and] to decision-makers, both Big P policy that we talk about in health policy related to legislation, things like that, but also Little P organizational policy.

That is another metric of success, that this work is able to be taken outside of conferences like the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium. [A metric of success is] it can be used to advocate for greater resources for individuals living with metastatic cancers, greater insurance coverage, [and] to have more robust and holistic support within cancer centers and the physical place of care for metastatic survivorship.

That is my metric of success: to see this impact policy both at the large federal, state, legislative, executive level, but also in the organizational, institutional policy and how we think about metastatic survivorship.

What is your connection to cancer research?

Dr. Roberson: My connection to cancer research is both personal and academic. I have a long family history of cancer in my family. My sister, my aunt, [and] my grandmother were all cancer survivors. It was just something that I had grown up around in a way.

For me, I gravitated towards breast cancer kind of in the academic space [by] sitting in a classroom very early in my educational career. I saw a figure that many of us know very well that shows the mortality differences between Black and white women with breast cancer.

[It showed] how we’ve gotten better at treating breast cancer over time, but Black women and other women of color have not found those same advances. Many members of my family have gone on to have very rich, robust cancer survivorship experiences. I want that to be realized for all.

[It was] that blending of personal experience, seeing the impact that cancer has had on my own family, with that encounter in an academic space with this very real inequity that we see in cancer, and really marrying those to move the needle and help make more equitable cancer care for all.

Conclusion

Lesley G.: Not everybody is going to be a patient advocate. Not everybody is going to have their voice heard. While I’m very passionate about patient advocacy, I didn’t start advocacy when I got cancer. I was always an advocate. I was an advocate before I even got my metastatic breast cancer community for the marginalized communities where I lived.

I always wanted to be the voice for those that were voiceless. I want to continue to do that for as long as I can. Another thing that is very important to me is I think about my kids. I think about people who live with metastatic breast cancer. I think about their children.

What I would like to see happen is that the work that is poured into right now, the things that we are bringing a voice to, the things that Dr. Roberson is researching, that if something happens… We think that cancer could never touch our families, and then we’re surprised when they are.

But wouldn’t it be great if all of these things came together, we could have equitable care, we could have the right kind of care for survivorship and thrivership, we wouldn’t have to fight for it, that our voices have already been heard, and we’ve laid that foundation so that we can be sure that those loved ones of ours do not have to go through what we went through to fight for our rights to live well?