Navigating Clinical Trials for Lung Cancer: A Patient’s Guide

Is a Clinical Trial Right for Me?

Edited by:

Katrina Villareal

Understand the different lung cancer types and the significance of biomarker testing through this recorded conversation. Learn about the evolution of biomarker testing inclusivity for all patients. Know more about KRAS and EGFR biomarkers, available treatments, and ongoing clinical trials.

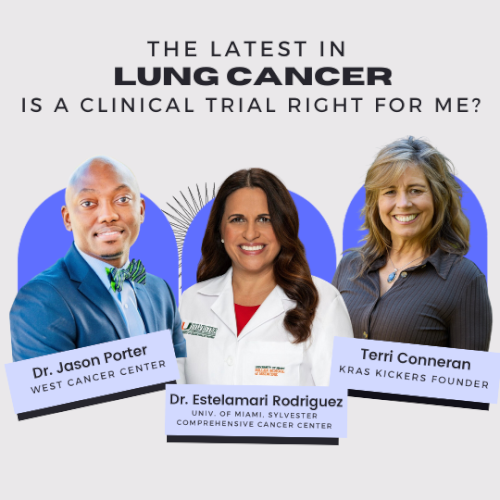

Leading experts Estelamari Rodriguez, MD, MPH, from the University of Miami Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center, Jason Porter, MD, from West Cancer Center & Research Institute, and Terri Conneran, founder of KRAS Kickers discuss the latest in lung cancer treatments.

This program was produced in close collaboration with our partner KRAS Kickers. We thank them for their time, expertise, and passion.

Get expert insights on current and promising clinical trials. Find out the importance of proactive patient engagement in finding suitable clinical trial opportunities.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider to make informed treatment decisions.

The views and opinions expressed in this interview do not necessarily reflect those of The Patient Story.

- Introduction

- Different types of lung cancer

- Different lung cancer biomarkers

- Tissue biopsy vs. liquid biopsy

- Most common types of lung cancer biomarkers

- Latest clinical trial updates

- Smokers & non-smokers

- Mike’s lung cancer story

- Joann’s lung cancer story

- Importance of getting a second opinion

- Clinical trials are NOT a last-ditch effort

- New immunotherapy trials

- Looking for clinical trials

- Different stages of a clinical trial

- Eligibility criteria for clinical trials

- Final takeaways

Introduction

Stephanie Chuang, The Patient Story: Hi, everyone! I’m Stephanie Chuang, founder of The Patient Story and a cancer survivor myself.

The topic of clinical trials can be pretty daunting. Some may know a lot and some may not even know what a clinical trial is. We’ll try our very best to cover as much ground as possible with our incredible panelists.

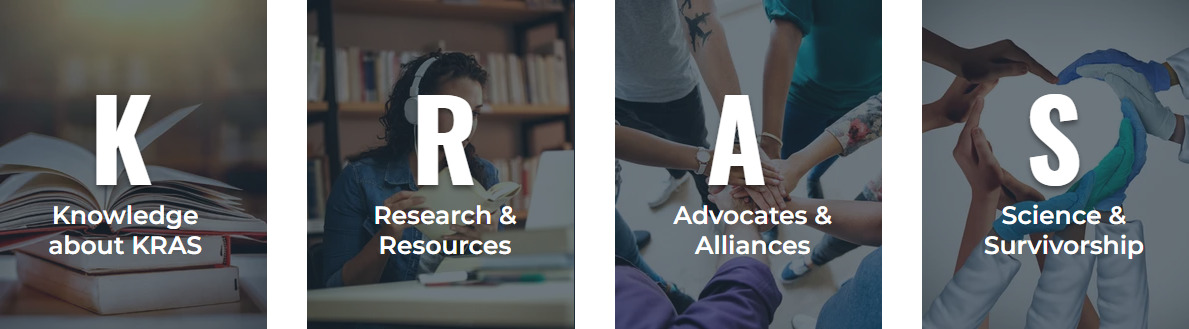

We’re collaborating with KRAS Kickers, a grassroots nonprofit led by patient advocate leader Terri Conneran, who will lead the discussion devoted to KRAS: knowledge + research + advocacy = survivorship. Their focus is on any KRAS oncogene or cancer type with the mission of connecting people to the latest research resources and community.

We’re co-hosting with them here at The Patient Story. I founded the patient and care partner organization after my own cancer experience, going through hundreds of hours of chemo, and feeling really alone.

Our mission is to humanize cancer so you know that you are not alone. We also invest in educational programs to help empower you and your loved one in your own care. We cover cancers across the board, including lung cancer, with a focus on biomarkers and clinical trials.

We want to stress that The Patient Story and KRAS Kickers retain full editorial control of this entire program. This program is not meant to be a substitute for medical advice. We want you to walk away knowing more, but please consult with your own medical team before making decisions.

Terri Conneran

Stephanie: Many of you may have already seen or heard our patient advocate moderator, Terri Conneran, who shared her story on our platform. I’m very lucky to call her a friend now.

Terri, a lot of us know how passionate you are as an advocate. You’re out there making sure people know how to be empowered in their care. Can you share more about your personal story and what led you here?

Terri Conneran: It’s such a blessing to be anywhere after you get diagnosed with lung cancer. I was diagnosed with non-small cell lung cancer, went through chemo and surgery, and had no evidence of disease.

I connected with other lung cancer groups and heard about biomarkers. Not getting the information I needed or wanted from my doctor, I eventually, after about two years, got a second opinion. The second opinion doctors told me I had KRAS.

I wanted to connect with other people so that we can all learn what this means and how we can make it better to live with KRAS cancers. We need to take KRAS and turn it into knowledge + research + advocacy = survivorship. We’re all here together to kick cancer’s KRAS so I’m delighted to be here. This is all about the hope that we’ve learned over the years.

Dr. Estelamari Rodriguez

Terri: We have Dr. Estelamari Rodriguez, a hematologist-oncologist at Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of Miami Health System. She specializes in early detection and treatment of lung cancer.

Dr. Estelamari Rodriguez: Thank you for the invitation. Delighted to be here.

Dr. Jason Porter

Terri: We also have Dr. Jason Porter, a hematologist-oncologist at the West Cancer Center Research Institute in Memphis, Tennessee. He’s the director of the Lung Cancer Disease Research Group and specializes in treating patients with molecularly-altered lung cancers and lung cancers with no actionable driver mutations.

Dr. Jason Porter: I’m super excited. Estela, it’s so good to see you again and I look forward to the discussion.

Different types of lung cancer

Terri: We’ve got a lot of ground to cover. Dr. Porter, what are the different types of lung cancer?

Dr. Porter: When somebody is new in my clinic, they want to know, “Do I have the really bad one or the one that’s not so bad?” Most people have heard that small cell lung cancer (SCLC) is more aggressive so that’s in the back of people’s minds. Basically, what it means is when we look under the microscope, how do the individual cancer cells look? Are they big or small?

Non-small cell (NSCLC) is the same thing as saying large cell or cells that aren’t as small under the microscope. We divide that into three categories: non-squamous, squamous, and large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma. Outside of those three, there are other rare histologies that we don’t see quite as often, but those are the more common ones.

Adenocarcinoma is the most common type of lung cancer and the most common non-small cell lung cancer then it’s squamous cell carcinoma. Large cell neuroendocrine is a different type of tumor.

When we look at the patient’s body, the trachea breaks off to the left and right lungs and squamous cells line the the epithelium; that’s the type of tissue that we see in the upper airways. Adenocarcinomas happen more peripherally in the lung fields. Small cells can pretty much happen anywhere.

Biomarkers are genes that drive cancer. We have been successful at identifying at least 10 of those.

Dr. Estelamari Rodriguez

Different lung cancer biomarkers

Terri: Dr. Rodriguez, what are the different biomarkers?

Dr. Rodriguez: When I started my training, we only knew about lung cancer as non-small cell and small cell. Now we really need to dig deeper into the genes that caused the cancer because today, we have 10 biomarker-driven treatments for specific types of cancers.

We know that a lot of these genes, mutations, and oncogenic drivers first described adenocarcinoma, but there are mutations in any type of cancer.

If you have a diagnosis of advanced lung cancer or even earlier stage lung cancer, it is important not only that you get a biopsy so that you understand the histology and how it looks under the microscope, but that you get that test about the genes that caused cancer.

Biomarkers are genes that drive cancer. We have been successful at identifying at least 10 of those, although a lot of them have been seen in adenocarcinoma.

Initially, they were in never smokers. We see them on people who have smoked a long time and who stopped smoking a long time ago so it really has nothing to do with smoking history. It has nothing to do with gender. It just has to do with the cancer.

It’s part of the information that’s critical to get at the beginning of the treatment so that you can pick the best treatment for the patient. A patient that gets started without that information may not be started on the right treatment. It’s important to do that test. It’s usually ordered in the tumor specimen or through a blood test called liquid biopsy.

Tissue biopsy vs. liquid biopsy

Terri: Is there a difference in what comes back from the liquid biopsy compared to a tissue biopsy?

Dr. Rodriguez: The gold standard of where we think we are most likely to find a source of the genes is going to be the tumor. But many times when you do a biopsy, you get part of the tumor that is very necrotic or dead tissue so the actual DNA inside that tumor is not good enough to get all the information that you need. You learn more from the blood.

The opposite can also happen. You can have a blood test that’s completely negative in terms of actionable mutations, but there’s a lot in the tumor specimen.

A lot of centers, mine included, try to do both tests because they can be complementary and specific. You can identify some mutations through the blood, especially RNA fusions where two genes come together.

With the blood test, we can do that in the office and get results in 7 to 10 days. Technology has allowed us to treat patients faster with the right treatment that we didn’t have available 10 years ago.

We’ve now discovered that we need to do biomarker testing in all lung cancers.

Dr. Estelamari Rodriguez

Most common types of lung cancer biomarkers

Terri: What are the most common types of biomarkers in lung cancer, Dr. Porter?

Dr. Porter: A long time ago, we found EGFR as a biomarker and then we have also the KRAS mutations. We actually found KRAS a long time ago and couldn’t target it for such a long time. It can serve as a biomarker that we can use to target for treatment and also a prognostic biomarker that gives us some information about how a tumor may behave.

We have both prognostic and diagnostic biomarkers outside of KRAS as well. We have PD1 and PD-L1, which are proteins that we can study to give us an idea about how our immune checkpoint therapies may work when we treat non-small cell lung cancer.

We also have BRAF, ALK, ROS1, and all these different proteins that may be driving the cancer or giving us information on how different cancers may respond to treatment.

We used to associate these biomarkers with non-smoking and now we have drivers that are actually associated with smoking.

Testing biomarkers is becoming very important for all patients regardless of their smoking history. BRAF is one of those biomarkers that we can see present in smokers as well as KRAS. MET exon 14 is another biomarker that’s also an actionable biomarker that we can target in therapy that may be associated with smoking.

We’ve now discovered that we need to do biomarker testing in all lung cancers.

Terri: Dr. Rodriguez, with the biomarkers, are you either one or the other?

Dr. Rodriguez: The world has become more complex as technology has allowed us to really dig in. It’s an alphabet of different mutations that are in each of these genes.

For example, with EGFR, the more common mutations are deletion 19 or exon 21 changes. But when you look at that whole protein, there are a lot of insertions and atypical mutations that we used to ignore because we didn’t identify them very commonly and we didn’t think that they mattered. But they do matter.

We have drugs developed, for example, for EGFR 20 insertion, which is something that was there all along and unrecognized. Those patients were not responding to the traditional treatments for EGFR because they had a different configuration of that protein so they needed a different type of drug to work.

The same thing with KRAS. There are a lot of KRAS mutations and it can be a whole alphabet of different KRAS mutations. KRAS G12C, which is a bigger proportion of those KRAS mutations, has two newly approved targeted therapies that we can offer.

We also see patients who have other types of cancers in other parts of the body who share these KRAS mutations and they may be of a different variety.

Because they’re all different, we have to invest in research to really define the best treatment for each of these parts of the mutation that the patient is encountering.

Testing biomarkers is becoming very important for all patients regardless of their smoking history.

Dr. Jason Porter

Latest clinical trial updates

Terri: We just came out of the big annual World Conference on Lung Cancer. Can you tell us some of the excitement that happened around KRAS or EGFR?

Dr. Rodriguez: Two things are happening. We’re getting more data from patients who have been treated for a long time in whatever option we had, like osimertinib, which is the first drug used for EGFR. We’re learning that people progressed. The next question is: how can we treat those resistant clones earlier?

One of the exciting data that came out was FLAURA2, a trial that used the same backbone of osimertinib, which is the targeted therapy that we use for most patients, and added chemotherapy. The question was: would patients do better if they had proper targeted therapy along with chemo? Will they be able to decrease the burden of disease and be managed better to prevent resistant clones in the future? That’s one of the theories.

I was happily surprised that it made a big difference. I always used to think that osimertinib works very well. You get a lot of responses. Then when it stops working, you can try chemo. However, I didn’t expect that patients would have almost nine months of improvement in disease. They were less likely to relapse if they were getting chemotherapy upfront.

With that same concept of making the treatment upfront more aggressive, there were other antibody-drug conjugates that were presented. We’re going to see a lot of exciting data with these new drugs that bind our receptors and inject chemotherapy into cells.

For EGFR, we saw a trial called HERTHENA that used patritumab, which is an antibody to HER3, which is another antibody similar to EGFR. It basically would inject chemotherapy into those cells that have become resistant. We saw data for that and there’ll be trials adding that antibody-drug conjugate to the first-line therapy.

We also saw the MARIPOSA trial, which is a drug approved for EGFR 20 insertion, trying to use that drug, which is an antibody-type drug, upfront with an EGFR inhibitor called lazertinib.

There’s a lot of excitement about combining drugs, not sitting back and waiting for things to happen, but trying to be more proactive. The data that was more mature was the FLAURA2 trial in EGFR.

Dr. Porter: KRAS, as I talked about earlier, is a very interesting biomarker because we’ve known about it for such a long time. One of the clinical trials in KRAS is the KRYSTAL-1 clinical trial. We have two drugs that are approved right now by the FDA for second-line use for KRAS G12C: sotorasib and adagrasib.

The KRYSTAL-1 clinical trial is a phase 1/2 clinical trial of patients with different tumor types that had KRAS G12C mutations and the non-small cell lung cancer cohort was included. We have data that continues to mature and we see response rates of around 35% in the non-small cell lung cancer cohort. These were patients with both smoking and non-smoking histories, mostly male patients.

As the data continues to mature, particularly in non-small cell lung cancer, it’s now been FDA-approved for use in the second line after patients progressed on an immune therapy-based treatment, so an immune therapy plus or minus chemotherapy.

Very interesting to see that, as Dr. Rodriguez alluded to with the FLAURA2 trial where we’re adding chemotherapy to targeted therapies, what the tolerability is going to look like and whether it is really going to cause benefit.

In KRAS G12C targeting in clinical trials, we have further study with adagrasib, which is looking to add chemotherapy to adagrasib with an immune checkpoint inhibitor.

It’s becoming a much more robust combination of therapies in the more advanced setting for KRAS G12C patients, where we’re familiar with the fact that KRAS G12C patients are more likely to be smokers so they’re probably having other co-mutations that may additionally be driving the tumor outside of KRAS G12C. This is where it becomes particularly interesting for me to see the addition of chemotherapy to the KRAS G12C inhibitor so that we are covering clones or parts of the cancer that are not actually being driven by the KRAS G12C mutation.

It will hopefully increase not only the outcomes for those patients, but also the response rates will hopefully be higher as we see with the EGFR inhibitor plus chemotherapy, and then the duration of response and survival for those patients.

Starting out with sotorasib and adagrasib now approved in the second line and then adding chemo and immune therapy to those drugs in more advanced settings upfront to hopefully improve outcomes, durations of response, and survival for those patients.

Terri: Essentially, it’s not like I only have one biomarker and that’s it. There’s a little bit more to it. There may be a biomarker that comes on down further or not as a result of treatments or what have you, but that makes a difference. Am I tracking with you?

Dr. Porter: Absolutely. It makes a huge difference. In the case of EGFR, as Dr. Rodriguez talked about, it’s more likely to be that one single biomarker that we need to focus on, maximize response, and benefit from targeting that pathway. But when it comes to KRAS, we know that there can be so many other drivers along with it.

Essentially, when I think about it, I think about if this patient were a smoker or if they had environmental exposures, they wouldn’t have one single driver. They may have other carcinogenic consequences from being exposed to cancer-causing agents like what we have in smoking or the environment like radon so more than one gene may be affected as opposed to these single gene-driven tumors like EGFR, ALK, and ROS1.

Dr. Rodriguez: The other thing that has become clear to me is that patients need to empower themselves with this information. There have been many cases in which I have seen second opinions or patients whom I have gotten to know where the information was there, but it wasn’t acknowledged.

They had a test earlier on in their disease and it was ignored because it wasn’t what the doctor was doing at the time. Either the patient went to surgery and they had a KRAS G12C mutation that wasn’t recognized or the patient had chemotherapy-immunotherapy and then that was not acknowledged and the patient missed an opportunity to get treatment earlier that we know can work.

Another part of this is understanding that science moves and there are new options and new combinations, but that you can’t make any decisions until you have the information in front of you.

We really need to be very strategic about what the treatments are. If you don’t have all this information going into it upfront, you can’t be strategic at all.

Terri S.

Terri: It is an exciting time. I’d love to drill down a little bit deeper into some of the clinical trials and what you guys are hearing and seeing.

Dr. Porter: For me, particularly with KRAS, the excitement got a little bit curtailed with the toxicity that we see sometimes when we add G12C inhibitors with immune checkpoint inhibitors. We may see a little bit more immune-mediated side effects like hepatitis, pancreatitis, and type 1 diabetes development.

The tolerability with the combinations was a little bit unnerving initially, but I think we felt the same way about immune checkpoint inhibitors when we first started using those, even in monotherapy. Imagine the experience with that first pneumonitis and the first dermatitis. I had a patient the other day who had some mucosal issues from immune checkpoint inhibition alone.

When we first encountered these, it was very unsettling. But now we feel so much more comfortable with these side effects. It’s really, really exciting to see the combinations of KRAS inhibitors with chemo, plus or minus immune therapy.

Right now, the unlikelihood of KRAS inhibitors being used in front-line monotherapy, to see those, explore the toxicity, and figure out how to use them in combination, modify doses, and do all of these things is very exciting. I assume, like we see with EGFR, that it’s going to improve outcomes when we’re able to bring them in combinations.

Any combination is very exciting. G13 is exciting to me, too. Again, I’ve only seen two in clinical practice and the first one was really a surprise to me. As we develop these pan-RAS inhibitors, again, more excitement for me.

Dr. Rodriguez: It was also seen in EGFR, but this whole message of treating patients earlier with chemo and targeted therapy really got my attention. In our practice, we have seen patients who have this mutation but have to wait for second line. We have to go through chemotherapy and immunotherapy and some of them get very sick. It’s very sad to me that they never got to see that targeted therapy.

In the trial that combined carboplatin-based chemotherapy with adagrasib, they saw responses of over 60%. They were able to bring up the responses that you wouldn’t see with chemotherapy.

Patients sometimes get a good chance to decrease the burden of disease. We know that some patients with KRAS mutations have a lot of burden of disease. It’s very aggressive. They have a lot of symptoms so if we’re able to help them with all our drugs upfront and we can find a way to deal with the toxicity, we’ll be able to help more patients.

Dr. Porter: Earlier, they’re more likely to tolerate a more robust regimen. It’s also exciting to get to do that a little bit earlier. We suppress the subclones that are being driven by the driver that we’re targeting.

When we aren’t able to use chemo and/or immune therapy upfront, those other clones that grow through are resistant to our therapy and may even be more resistant to chemotherapy later so we see lower response rates.

Where we have these drivers in the second line, it’s really sad to see those patients come to that point and be clinically unable to tolerate whatever the therapy is.

I had a patient with a G12C mutation who wasn’t a candidate for a clinical trial in the front line. When we got to the second line, his effusion was refractory, even loculated, and not amenable to easy drainage. He was definitely not a candidate for VATS (video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery) where we go in and clean that out so trying to get him onto the G12C inhibitor wasn’t possible. He couldn’t tolerate it.

He spent most of that time hospitalized and eventually went into hospice. When I first met him, he was walking into the clinic and still robust. Being able to target at that time would have really been nice for him.

Terri: We really need to be very strategic about what the treatments are. If you don’t have all this information going into it upfront, you can’t be strategic at all.

We want to forget the actual stigma but remember that stigma is a problem.

Dr. Jason Porter

Smokers & non-smokers

Terri: You mentioned that the EGFR group of patients is equal to the amount of KRAS G12C patients and yet they’ve had a whole lot more studies and a lot more drugs that have been going on.

We’re not there yet when it comes to other KRAS subtypes, let alone some of the others as well. You both brought up smoking. Is it that important where it got here from or is that one of those things that keeps getting reported out?

Dr. Porter: For me, it’s not important where we got here from, but what we have to remember is stigma. We want to forget the actual stigma but remember that stigma is a problem.

The reason I always bring up smoking is because I was sitting in a room with a very, very smart oncologist who told me, “This patient was a smoker so they’re less likely to have an oncogene driver.” I said, “Twenty years ago or 30 years ago, that would have been true.”

I like to use smokers, next-generation sequencing (NGS), and studies in the same sentence so that people start to make the association that you can definitely have a driver that’s actionable even with a history of smoking. You’re more likely to find BRAF, MET exon 14, and even KRAS with FDA-approved therapies in smokers.

Where it becomes relevant for a never smoker is we know they’re less likely to respond to immune therapy by itself. But for smokers, I like to keep saying that and putting NGS testing in the same sentence so people stop having this association that the oncogene driver patient is a young female, Asian, never smoker. That’s what we learned in medical school. We need to really change that narrative.

I don’t want it to seem like I’m harping on smokers. I’m harping on the fact that smokers can have drivers and that we have to study everybody. We have to.

Terri: Thank you for clarifying that because that’s exactly what I was hoping you would say. We definitely need to test and it’s important for what’s next.

We have two fantastic patients who went through clinical trials.

I highly recommend a clinical trial to anybody, but do your homework. Have an exit strategy in the event something happens or a side effect you cannot tolerate.

Mike S.

Mike’s lung cancer story

Mike S.: I have stage 4 lung cancer. I was diagnosed in 2016 and like most people, I was stunned, particularly since I was a non-smoker.

It’s been an uphill roller coaster ride, depending on what kind of medications I’m on, the side effects of those medications, or the availability of certain alternative treatments that I’ve been on for the last couple of years, including a clinical trial drug.

My initial diagnosis put me on the standard of care treatment and that lasted about 27 months. The efficacy rate was about 24 to 26 months.

In discussion with my oncologist and also with what treatments were available, I was presented with TAGRISSO, an FDA-approved drug, or I could go on a clinical trial.

Our thinking here was that if I went on a clinical trial drug that was supposed to work as well or better, then I could perhaps extend my life. They’re proposing that this clinical trial drug had an efficacy drug of two years versus an FDA-approved drug that had an efficacy rate of about three years. This particular drug was thought to be better than the FDA-approved drug.

I’m going to get scanned more frequently. I’m going to get a report card of my tumors. There’s a lot more testing, monitoring, and scanning that takes place because you’re on a clinical trial.

The additional monitoring was what prompted me to say yes to the clinical trial. I may have the benefit of getting additional months added to my life with the efficacy rate of a potential clinical trial drug working for a period of time.

Before I started the clinical trial, I met one of the nurses who was going to be assigned to me. She was great and explained the whole process. She also helped facilitate the scans, progress reports, meetings, and discussions.

I was one of the earlier ones to get in, but there weren’t a lot of people in the clinical trial. There was no drug name. I believe it was in phase 2 when I got involved.

Initially, I did really well. I had a reduction in tumor size. I was just astonished. I was getting monthly progress reports showing tumors shrinking so I was flabbergasted.

I made the right decision because the benefit of this is I got on a clinical trial that’s working. Even if it fails at some point, I’ve got a reduction in tumors. I’ve got an extension of life.

That lasted for about 10 months then the worst happened. I had a brain scan and it showed five brain mets. I reached out to several people in the lung cancer community who had similar situations but not from the use of a clinical trial drug.

Because they had brain mets, they switched to Tagrisso, which I had put off moving to because I wanted to try the clinical trial drug. Tagrisso was supposed to ward off any type of brain mets but also eliminate them if you had them.

I knew exactly what was going to happen if the clinical trial drug failed, which was to go on Tagrisso, in discussion not only with my oncologist previously but also with about 5 or 6 different lung cancer patients I knew.

I was pretty calm about this even though the placement of some of these brain mets was not good. I had one of my brain stem, which essentially made it inoperable.

When I went in, I saw the oncologist, the oncologist nurse, the nurse navigator, the social worker, and the nurse assigned to the trial. I thought this couldn’t be good because I don’t usually meet with a parade of people like this.

The discussion centered on some of the results and the five brain mets. I said, “What we’re going to do is move to Tagrisso, correct? When you tell me it’s inoperable, you can’t do anything. You can’t do radiation, right? I’m out of the trial. The intent is that this drug is going to eliminate these brain mets.” He said, “That’s correct. That’s our hope.” I said, “Okay, well, then that’s what we’re going to do.”

They were all looking at me like, “Wow, does this guy have nerves of steel or something or is he crazy?” I wasn’t reacting in the way they thought I was going to react. I was informed at the start of the trial what may happen. When I got negative results, I did the research, too, before I met with my oncology team.

After we met, everybody left the room and then a moment later, the nurse came in, gave me a big hug, and said, “Are you okay?” I said, “Yeah, I am. I know it’s what I was in for when I signed up for this. You are working to save my life and we’ve got a plan. I’m fine as long as we have a plan.”

What I don’t like is when something happens in the roller coaster journey of having lung cancer and you don’t have an established plan and you’re waiting for something. That’s when it gets a little bit more nerve-wracking.

There’s a lot of paperwork associated with the clinical trial because there’s the acknowledgment of the risks associated with going on a drug that you don’t know what it’s going to do to you. There’s an assignment of a lot of pages to read through and sign.

The nurse associated with the clinical trial did a very good job of explaining the risks associated with being on this drug. I didn’t have any problems with understanding the risks.

Prior to getting on the clinical trial drug, you had to do tests. I got off the prior drug for maybe a week or so before I started the trial to make sure I didn’t have any prior drugs in my system.

There are some attestations that you didn’t use the drug or any other drugs prior to starting the clinical trial. The attestations are pretty straightforward. They ask a lot of other questions.

For anybody who’s considering a clinical trial, do your homework not only at the front end but also at the back end. It’s not just about getting on the clinical trial drug. At some point, you’re going to get off the clinical trial drug. Generally, there’s an exit strategy.

I got out early because I developed brain mets. How the trial ended or not is confidential information. I had some conversations with my oncologist and the nurse associated with the study because they had to provide information to the clinical trial provider.

I highly recommend a clinical trial to anybody, but do your homework. Have an exit strategy in the event something happens or a side effect you cannot tolerate. You have an entry plan and an exit plan. Make sure you’re covering your bases with all those questions before you get on the drug and then be prepared for what may happen.

I had an extension of life for 10 months, but had I not gone on it, I would have gone on some other drug that had a different efficacy rate. I would wholeheartedly do it again in the availability of a clinical trial drug that meets my particular criteria.

It’s more important to get the right treatment than it is to get a treatment quickly. Ask as many questions as you can and don’t be afraid.

Joann J.

Joann’s lung cancer story

Joann J.: I was diagnosed in November 2021 with stage 4 non-small cell lung cancer KRAS G12V. I had several standard-of-care treatments, all of which resulted in progression. Luckily, I got on a clinical trial in February 2023. It was a targeted therapy and it was a daily pill, which was wonderful. No more infusions.

I had a great quality of life for six months with very minimal side effects. I was able to go back to work. I was in a really good place.

Unfortunately, my last scan showed progression and new growth, which is unusual for a targeted therapy. I have an upcoming biopsy on the liver, which is where the new growth is, and based on the results, we can figure out how to move forward.

My biomarker is KRAS G12V. We’re doing this liver biopsy to make sure that it’s the same cancer. I think the next step is another clinical trial, probably immunotherapy.

Through KRAS Kickers and Terri, it’s definitely something that I researched and looked into. The first time this particular clinical trial was mentioned to me was through my oncologist in New York. I was put on a waiting list.

I traveled to Dana-Farber in Boston and to MD Anderson in Houston to hopefully get on the trial sooner. Interestingly, Dana-Farber and MD Anderson would not allow me because I had a history of pneumonitis.

MD Anderson was going to put me on a different trial. I was all set to get an Airbnb and move to Texas for six months when, all of a sudden, they had a spot for me in New York for the RMC-6236 trial.

I definitely feel like my knowledge of the clinical trials and my aggressiveness in the whole process certainly helped me.

My only fear was whether or not I was going to get a drug or a placebo. From what I gathered, they don’t give placebos to cancer patients. It’s just cruel. Once I understood that, I was and still am very willing to go on any trial. It’s the future of cancer treatment so I have no problem.

I had a good experience and I know other people have not. When I went to MD Anderson, my insurance company paid for my airline ticket plus my husband’s. Things like that are very difficult. The financial toll is significant. In that respect, I feel very lucky. But I also feel like KRAS Kickers has definitely given me knowledge and, with that knowledge, strength.

For someone who may be considering a clinical trial, I would say go for it. Ask as many questions as you could possibly think of. A second opinion is always a good idea. It’s never a bad idea.

In fact, even if they don’t give you a different direction, the peace of mind you get is invaluable, knowing that the direction you’re going in now is the right way to go.

The first thing I learned in the cancer community is it’s more important to get the right treatment than it is to get a treatment quickly. Ask as many questions as you can and don’t be afraid.

Terri: Those are some powerful stories. These are real people who are doing these clinical trials. Pretty amazing.

Dr. Porter: It really is. To hear Mike’s excitement about the clinical trials and to hear how he thought about what the possibilities were as it was being presented to him, it’s really exciting. He really captured some of the things that our patients ask us when we bring up clinical trials and what they can expect.

Dr. Rodriguez: We don’t hear enough from people who have a good experience in a clinical trial. We have a lot of patients who think that they’re going to be experimented on and that they’re going to be getting a placebo.

I work in an experimental therapeutic clinic where everybody gets a drug. We’re not giving placebo drugs for phase 1 trials or phase 2 trials. They’re all about testing a drug.

We don’t know how well those drugs would work, but one of the things that has really changed in oncology is that we’re getting results faster and drugs faster for patients. Sometimes not as fast as you will need them, but much faster than they used to be.

Biomarker testing has allowed us to do better trials because now we can find the right patients who are more likely to respond to some of these treatment options. In the past, we will have a new drug and it will be given to everyone with or without chemo. The responses were obviously very low because you were not looking for patients who were more likely to benefit.

As a provider in one single location with limited resources, if I open the network and use everything out there, I exponentially increase the chance that my patient’s going to find something that’s tolerable and may be very effective for them.

Dr. Jason Porter

Importance of getting a second opinion

Dr. Rodriguez: I would encourage patients to think of second opinions as a good thing, not a bad thing. I have patients who come to me and say, “I’m sorry, I’m going to go speak to so-and-so.” I say, “I am delighted that you’re going to speak to someone else.”

We’re all friends. If you have a doctor that gets upset about this, it’s kind of odd. If I were going through this, I would want to learn from other people and get a different perspective. Maybe another doctor can see something that was missed. It is good to do that. You’re not going to hurt your doctor’s feelings and they’re not going to stop treating you.

Dr. Porter: Coming back from the World Conference on Lung Cancer in Singapore, I had a patient who was progressing. He said two letters to me, “MD,” and I was already typing an email to one of my colleagues at MD Anderson, saying, “Hey, my patient’s progressed and I don’t have a trial that’s right for him. Would you look at it?”

He’s going to see my colleague and it’s not about me or my feelings. I love my patient and I want him to be okay. I want to make sure he gets access to whatever is out there that may benefit him.

As Dr. Rodriguez said, if we get upset, it’s probably something odd about us. There’s really no reason to get upset. It takes a village and as a provider in one single location with limited resources, if I open the network and use everything out there, I exponentially increase the chance that my patient’s going to find something that’s tolerable and may be very effective for them.

Clinical trials sometimes give you the best therapy before it’s even available for general use.

Dr. Jason Porter

Clinical trials are NOT a last-ditch effort

Terri: It really is different than I thought it was because I’m not a doctor. I didn’t know anything about this. The surprise was that you don’t do clinical trials as a last-ditch effort. I had no idea there was an actual order to it, you qualify for it, and it matters a lot what your biomarkers are.

Dr. Porter: We don’t want to take it as a last-ditch effort because when we get ready to go on clinical trials, we have to control for as many variables as possible. Are the kidneys functioning okay? If something happens on the trial and the kidneys aren’t functioning well, it could be a complication of kidney dysfunction and then the drug gets associated with that unfortunate outcome. We have to control those things.

Earlier in a disease like lung cancer, you’re less likely to have some of those other disease issues that may exclude you from the clinical trials. Doing it earlier is better.

I came into my clinical practice around the time that immune therapy was starting to come into second-line FDA approval. I thought about the people who went on immune checkpoint inhibitor clinical trials, the ones who are still responding from 2013/2014. There are still some survivors. For those patients who went on early, the clinical trials sometimes give you the best therapy before it’s even available for general use.

Our guideline compendium says that the best therapy for a patient with lung cancer or with any cancer is in a clinical trial. If you end up getting in early, you have long-term benefits. Definitely not a last-ditch effort and sometimes access to the most effective thing available.

Identify the biomarkers early so you can get on the right track.

Dr. Estelamari Rodriguez

New immunotherapy trials

Terri: We had a question that was asked about new immunotherapy trials. Will previous trial patients be able to participate?

Dr. Rodriguez: That’s the beauty of earlier phase trials. The patients didn’t fail; the treatment didn’t work. You want to find a different way to treat them.

A lot of the trials that we do after immunotherapy is a new immunotherapy that is in a different way, a vaccine trial, or a different mechanism to try to wake up the immune system because, in a way, most tumors can possibly be treated with immunotherapy. They become what we call hot tumors that are more likely to activate the immune system. Some tumors lose that capacity. You have an innate resistance that is not a tumor that is very hot in that end and you can do something to it.

We have tried different things, like radiation followed by immunotherapy. There are a lot of exciting vaccine trials that are trying to push that immune response.

What we have seen success of is the memory of the T cells in a longer way, infiltrating T lymphocytes, which are white cells of your own body that get activated against the tumor and then given back to you to do a more directed immune therapy. Those are treatments that immunotherapy can possibly help patients with many different biomarkers.

Biomarker-driven research and treatment is very exciting because sometimes you get very deep and long responses.

Another exciting development is in the ROS1 and NTRK space. We had a new drug, repotrectinib. When we understand how you can bind these receptors and do better, then the next drug can have an even higher response. Some of these drugs have responses of 70% with intracranial responses that are over 40%. That means that we get better at the next generation of the drug.

That’s what I hope for KRAS G12C. We already have seen adagrasib and sotorasib have intracranial activity that is real.

I had a patient who I was getting ready for our next-generation KRAS inhibitor and I thought she was progressing. I did all the studies to get her ready for the trial. The one she was on was working very well. She had a response in the brain and the pleural disease she had went away. Identify the biomarkers early so you can get on the right track.

Terri: What a great problem to have that she was responding so well that she didn’t have to join the clinical trial.

Dr. Porter: Right, that’s exciting.

Patients can get a copy of their own biomarker testing. A lot of times, the results will list out the clinical trials that are relevant to that particular biomarker.

Dr. Jason Porter

Looking for clinical trials

Dr. Rodriguez: Patients who are most likely to go into trials are patients who have been on trials before. We have a lot of patients who had a good experience and that opens a whole new door of options for them. I would encourage people to look.

Fortunately, everything’s consolidated in ClinicalTrials.gov, a website where you can put in your mutation and your state, and get a readout of trials that are open. All of those trials have an email of an investigator and a nurse coordinator.

I do that for my patients. I say, “We’re going to write an email and you’re going to find out if this trial is open.” Sometimes there’s a trial right next door that you hadn’t even known about. You just have to do the work.

Dr. Porter: There is a lot of work.

If you are patient and your doctor is not really considering or giving you the option to discuss clinical trials, you may need to consider reaching out on your own, maybe get in touch with Terri or us, and see about what options may be there.

An amazing resource for finding a clinical trial is your doctor and that’s where you need to start. But obviously, you can’t wait in case that’s not presented as an option for you.

If a patient has access to their biomarker analysis or if they know they have any particular mutation, you may just search that mutation + clinical trials on the Internet and see what comes up. You may even type in your city to see what comes up in your city.

Patients can get a copy of their own biomarker testing. A lot of times, the results will list out the clinical trials that are relevant to that particular biomarker and even give you a listing of where those trials are.

We assume patients don’t want the information from the actual report of their next-generation sequencing but as we educate and get advocates out there, letting patients know how important biomarker testing is, they can find often a list of the relevant clinical trials for their biomarker right there on the report and that can guide them in their initial searches for clinical trials for their biomarker.

Dr. Rodriguez: We can forget that crowdsourcing for clinical trials is really one of the most effective ways. I have patients who have found trials because they were part of a patient support group. Someone in another state was in a trial and that opened up an opportunity to really look at a trial that was in the same state.

I had a patient who came from Jacksonville, which is pretty far from us, but she found the trial through the patient support group. You can reach out. People who have gone through other trials already have made connections and that can be very helpful.

Dr. Porter: A lot of patients want to know the purpose of a trial and if there are any risks associated with being in a trial. It’s a little counterintuitive, but if you think about it, you’re monitored so closely. Any risks are much more likely to be discovered while you’re on a clinical trial.

If there’s going to be any trouble with your kidneys or your liver while you’re on the clinical trial, which could happen with chemotherapy that’s already approved anyway, you’re going to be getting labs more frequently. You’re going to be coming in to see the nurse a little bit more frequently and possibly even phone calls from the clinical trial coordinators. You’re monitored a little bit more closely so I feel like it diminishes the risks that may be associated with the clinical trial.

Crowdsourcing for clinical trials is really one of the most effective ways. I have patients who have found trials because they were part of a patient support group.

Dr. Estelamari Rodriguez

Different stages of a clinical trial

Dr. Porter: As we get to the different stages or phases of the clinical trial, we have more experience with that particular drug so there’s even more information about what risks may be out there.

There’s a phase 1 clinical trial that Dr. Rodriguez mentioned that she helps facilitate at her clinic. That is pretty much the first time that these drugs are being used in a single agent or in combination with another chemotherapy or agent.

In phase 2 clinical trials, we have already established that it’s effective or that we can see responses so we want to study a bigger population. We’re seeing more patients now being exposed to the medication to confirm that it works.

In phase 3, we’re doing a much larger trial where we’re comparing it to what’s already considered to be the standard of care. This is the way we treat this, but now we have this new option, and let’s compare the two to see if one is better.

Those eligibility criteria are there to make it safe, although we do know that sometimes they’re too safe that they’re excluding patients who need treatment.

Dr. Estelamari Rodriguez

Eligibility criteria for clinical trials

Terri: Carina asks, “What are the typical eligibility criteria? My mom can’t do trials near her because of her poor ECOG PS and she’s on oxygen.” Give us some guidance.

Dr. Rodriguez: We need to develop trials for real-world patients. Because of their disease, some of them will be on oxygen. Patients will have brain metastases. They’re going to need clinical trials and many trials have excluded them in the past.

I’m very excited about the Pragmatica trial by SWOG; that has no lab requirements. They don’t need to look at your oxygen status. They just need a doctor who has a patient in front of them and they just want to evaluate their response.

We need to encourage more trials that are for patients who need them and have a lot of symptoms. Sometimes, these patients are too sick to go into a trial because they’re new drugs and we really don’t know how they’ll tolerate them or we have serious concerns about toxicity.

You have to trust your doctor that those eligibility criteria are there to make it safe, although we do know that sometimes they’re too safe that they’re excluding patients who need treatment. There is a big movement by the NCI to make trials for real-world patients.

Terri: That’s the direction we need to really go in because we’re real people and we need to have real-world access.

This is the fight of your life. If you’re not open to clinical trials, you’re closing your eyes to opportunities.

Dr. Estelamari Rodriguez

Final takeaways

Terri: What is the top takeaway that you hope our audience members leave with when it comes back to clinical trials in lung cancer?

Dr. Rodriguez: Don’t be afraid to ask about clinical trials because if you have a diagnosis of lung cancer where a lot of patients are going to progress, this is the fight of your life. If you’re not open to clinical trials, you’re closing your eyes to opportunities.

I always tell patients about those patients who went on immunotherapy trials and are alive 10 years later. It was as scary as the trials that we’re talking about now, too. No one knew that drug would work and look what happened. That drug worked and made a difference. It changed lives.

I want to give people the sense of hope that clinical trials offer hope. People who do clinical trials do get better outcomes because they’re monitored very closely for risks. Clinical trials give you an opportunity to do better and really push the envelope in a disease that can be relentless.

Dr. Porter: Clinical trials are very important. I would love for patients and caregivers to take away the need for biomarker testing. I know that we’ve heard it over and over again, but I don’t think we can express that enough because most of the clinical trials are biomarker-driven trials.

In order to find out if a patient is going to be a candidate for a trial, we have to have their initial biomarker testing done. Not only do we increase the likelihood of them getting a relevant first-line therapy, but we also increase the likelihood that at the time of progression, we will have a good clinical trial that may be available for them.

As patients, make sure you’re asking, “Did you do my biomarker test? What does my biomarker test say?” We can’t ask that enough. If you’re at the clinic with someone who’s been diagnosed with lung cancer or any cancer, ask, “Have you done any biomarker testing?”

As providers, it holds us accountable so that we make sure that we’re doing that for patients. We can then give them a good first line of standard of care and good clinical trial options when a clinical trial is not appropriate in the first line.

Terri: You need to know what you are so that you can take charge of what you’re doing because you’re the patient in this and it’s your skin in the game.

Stephanie: Thank you, Terri, Drs. Porter and Rodriguez. It’s so clear you’re so driven to help patients and their families. Thank you for the amazing conversation. We hope to see you at a future program.