The Latest in Genetic Testing in 2023

Featuring Sue Friedman and Abigail Johnston

Genetic testing can help people understand their risk for cancer, help them make medical decisions and detect cancer early. For those already diagnosed with cancer, genetic testing can play an important role in finding the best treatment options.

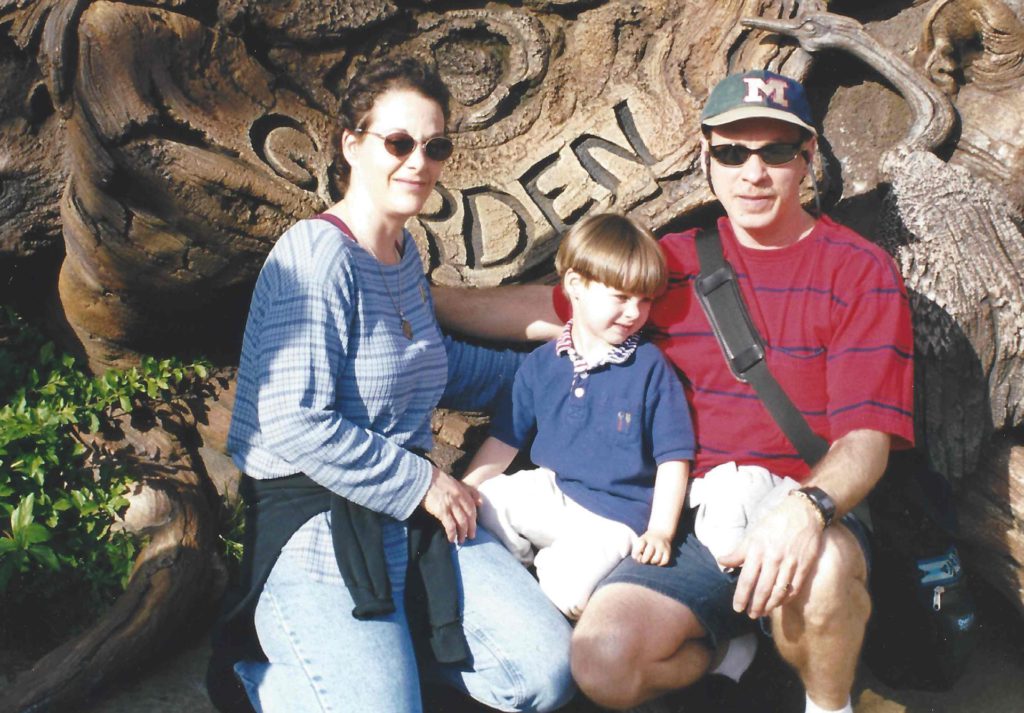

Abigail Johnston is a cancer patient advocate living with stage 4 metastatic breast cancer. Abigail has the ATM gene mutation, which carries an increased risk for breast cancer.

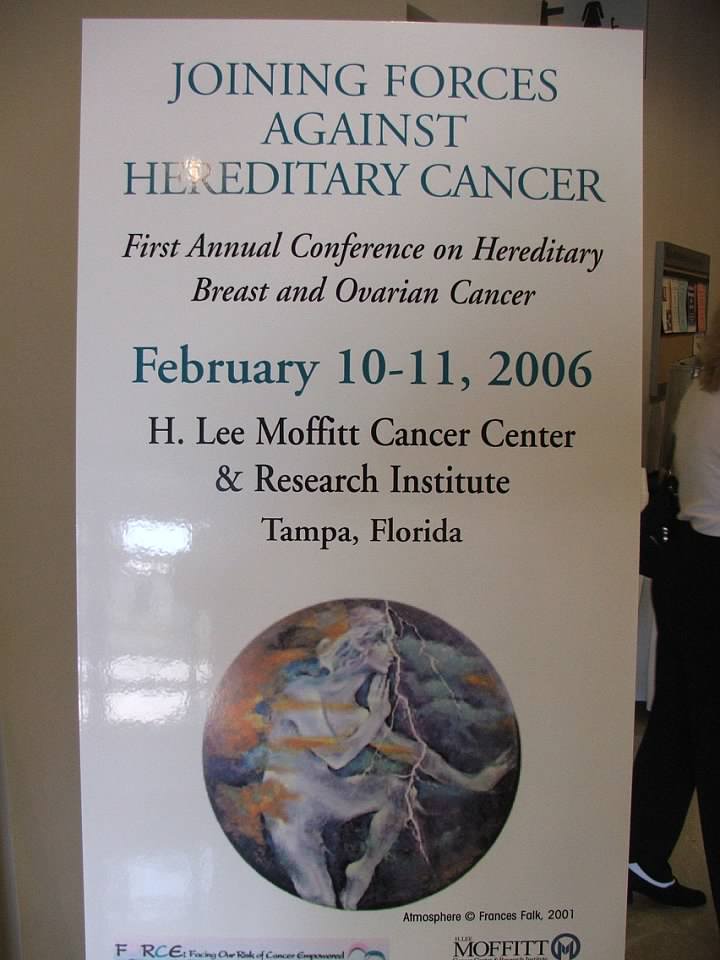

Sue Friedman is the founder and executive director of FORCE, Facing Our Risk of Cancer Empowered. Sue founded FORCE after being diagnosed with breast cancer and testing positive for the BRCA2 mutation.

They both attended the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium (SABCS) which provides the latest information in research, prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of breast cancer.

In this conversation, they break down what genetic testing is, the different types of genetic tests, what it could mean for you and your family and how to interpret the test results.

Brought to you in partnership with Project Life.

- Introduction to genetic mutations

- Sue, why did you found FORCE?

- Creating the term “previvor”

- Breast cancer and hereditary cases

- Reactions to finding out it’s hereditary

- Genetic testing

- Direct-to-consumer genetic testing

- Variant of unknown significance

- Genetics don’t guarantee you will get cancer

- Resources provided by FORCE

This interview has been edited for clarity. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider for treatment decisions.

Introduction to genetic mutations

Abigail J.: One of the most important things to know when you get a cancer diagnosis is how you’re going to be treated. Learning about your cancer [and] learning about the things that make your cancer unique helps the doctors make the best decisions in order to give you the best medicine that is specifically targeted to the cancer that’s in your body.

We’re learning a whole lot more. Doctors are learning things all the time about different biomarkers, mutations that they can target, [and] things within your body that respond differently, from one person to another. There are things that can be understood about different patients as groups.

One of those things are hereditary or germline mutations. These are mutations that come in your DNA. You get one-half of your DNA from your mom, one-half from your dad. Sometimes mutations can be passed down in families.

At a time of a cancer diagnosis, a lot of times that’s the only time that a family will suddenly find out that there are these sneaky little things going on in their bodies that they have no control over that mean they’re more predisposed to a cancer diagnosis, to diabetes, to heart disease, [or] to all kinds of different things.

Understanding those mutations in your DNA not only helps the doctors know what medications to pick, but then you can also do family planning. You can inform your families. There’s all kinds of really important things about knowing what is in your DNA.

Sue, why did you found FORCE?

Abigail J.: I’m super excited to have Sue Friedman here with us today, who is with FORCE, which stands for Facing Our Risk of Cancer Empowered, an organization all about making sure people understand what’s in their DNA and then know what to do with it. Sue, would you tell us why you founded FORCE? Where did it come from?

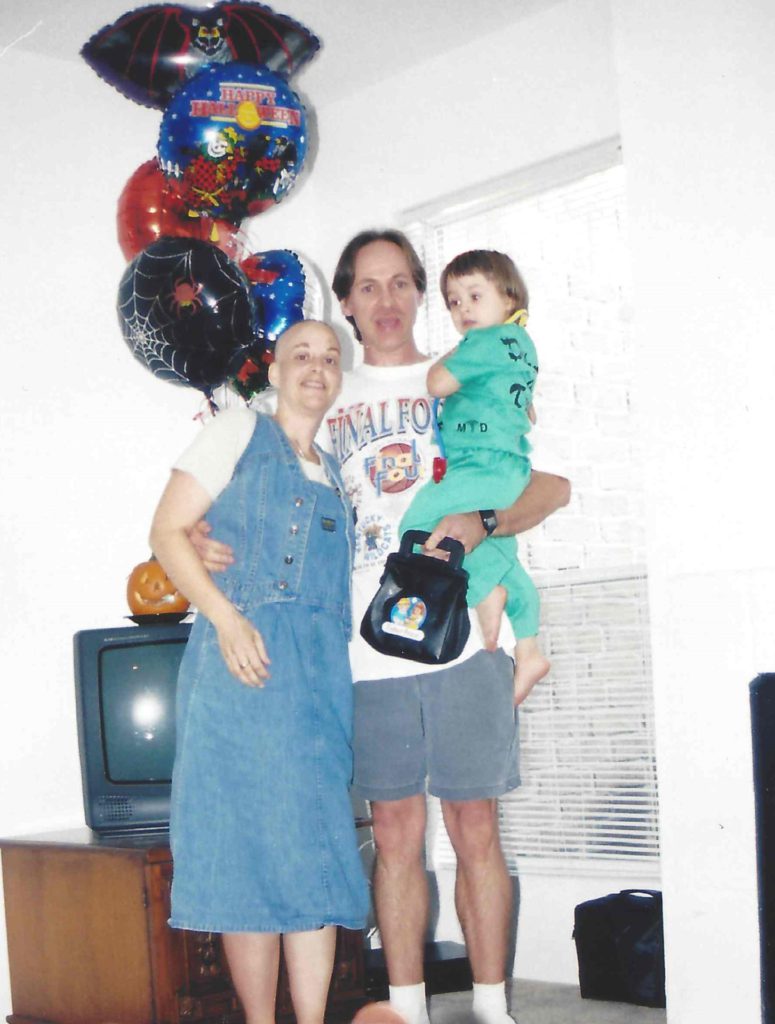

Sue F.: I was diagnosed out of the blue at age 33 with breast cancer, and I was very proactive with my health. I didn’t have a family history of breast cancer. It wasn’t until after I was diagnosed and actually after I had my initial treatment that I was reading a magazine article about hereditary cancers and about genetic testing for BRCA1 and 2. This was really many years ago, so kind of in the early days of precision medicine.

In this magazine article, they were talking about BRCA1 and 2 testing and how certain people are more likely to have an inherited mutation that can predispose them to cancer. I’m reading through these red flags, and one of them was young-onset breast cancer. I’m like, “Okay, that’s me. 33 with breast cancer.”

Then it was talking about a link between other cancers, like ovarian cancer. My paternal grandmother on my father’s side had some kind of abdominal cancer. They said it could be passed on from either side of the family, like you said. Nobody had ever asked me really about my father’s side of the family in medical intake forms.

All of those things together, and then they were talking about how people of certain ethnicities or groups are more likely to have a mutation, and that included Ashkenazi Jewish people. I was like, “Okay, I’m 3 for 3 here.” But my healthcare team never told me that.

I’m reading [it] in a magazine article, and I said to them, “I want this test.” They were like, “Sure, give us your arm. We’ll pull the blood. We’ll send it in.” Well, they never actually sent it in.

Abigail J.: Wait a minute. They never sent the blood in?

Sue F.: They never sent the blood in. I know.

Abigail J.: Wow.

Sue F.: There was no genetic counseling, and again, this was the early days of genetic testing. I also ended up having a recurrence soon after that. I ended up at a cancer center for a second opinion, and I told them, “I want this test.” They’re like, “Okay, you have to have genetic counseling.”

The idea was, though, to give a voice to a community that didn’t feel they had one.

Sue F.

I was halfway through chemotherapy when I found out I had a BRCA2 mutation. Suddenly, I had to make other decisions, too.

I had had a unilateral mastectomy for treatment, and suddenly I learned my other breast was at really high risk. I didn’t want to go through chemo and treatment again.

Then they were talking about my ovarian cancer risk. I didn’t think I was done with having children, but I felt like I didn’t want to go through another diagnosis. I had to make these really tough decisions, like do I end my fertility? Take my ovaries out? There really weren’t resources about that.

Abigail J.: Was your medical team helpful in making those decisions?

Sue F.: They were, but because this was such early days in genetic testing, it was a new test. They didn’t have a lot of long-term outcomes, so they’d say, “Well, we think this will lower your risk for ovarian cancer,” which makes sense. “We think removing your other breast is a good idea, but we don’t know. We don’t have long-term outcomes yet.”

I had to kind of make those decisions in a vacuum, at least an evidence vacuum. There were a lot of other people who I met who had breast cancer, and there were support services and support groups, but most of them weren’t making those decisions with regard to genetic testing and what to do with that risk.

I really felt the need. It was out of my own need that I started FORCE. I started as a lark. I didn’t even have a computer when I was diagnosed. Soon after treatment, I did take out my ovaries. I was newly postmenopausal at 35, so I spent a lot of nights awake with insomnia.

I’d be on these message boards, talking to other survivors. I started meeting these other people with mutations. Some of them didn’t have cancer, and some of them did, and they really had nowhere to go. That’s kind of why I started FORCE 24 years ago, to give us all a place to go.

Abigail J.: And 24 years.

Sue F.: 24 years. It just grew, and there was such a need. About 5 years into running FORCE, I actually made the very difficult decision to give up my veterinary career to do it full-time because there were a lot of great vets out there, but there was really only one organization providing resources specifically for that community.

Creating the term “previvor”

Abigail J.: I think I read recently that FORCE was behind the term “previvor.”

Sue F.: We were. One of the members of our community — and she actually happened to be a member of our board of directors — said, “I need a label. What am I? I don’t have cancer, but I know cancer. I lost my mom to cancer at a young age. I’ve lost my breasts to cancer risk. I lost my ovaries to cancer risk, but I don’t have cancer.” She said, “I’m not one for labels, but I need a label for this.”

What I realized then, too, was that there was this whole group of stakeholders that weren’t part of the conversation. Before I started FORCE, I’d go to support groups. I’d see some of these previvors go, and they were apologetic, like, “I know I don’t belong here. I’m sorry, I don’t have cancer.”

They were always apologizing, and sometimes they weren’t welcomed as stakeholders.

It was really for that population that FORCE became a real home. We kind of did a search of terms, and we came up with previvor for “survivor of a predisposition to cancer.” Not everybody loves the term, which is fine. The idea was, though, to give a voice to a community that didn’t feel they had one.

In that regard, whether people love it or we hear people say, “I don’t like the term; stop using the term.” We’re very open to other terms, but it did provide a community and a label for some people who really wanted more.

Breast cancer and hereditary cases

Abigail J.: When you look at the people who have been diagnosed with breast cancer, is hereditary breast cancer something that makes up a lot of the reason for a diagnosis, or is that a small percentage still?

Sue F.: It’s about 10% roughly. Many people don’t know that they have a mutation, but it can affect treatment decisions, it can affect prevention options, and it can affect your family members. It’s not just breast cancer; it’s other cancers as well. Knowing that information can be really important to medical decision-making.

It’s not like it’s the majority of people with cancer, but when you look across the spectrum of people who have been diagnosed with breast cancer and other cancers, these are often families that have a disproportionate cancer burden.

There are relatives. There’s siblings. There’s parents. There are children and cousins. The burden within some of these families is really, really high.

Abigail J.: Sure, because once you find one incident of hereditary cancer, everybody starts getting tested. In my particular family, when I was diagnosed with ATM — it’s not BRCA. It’s a different, lower, moderate risk for breast cancer.

I’m 1 of 6. One of my sisters is positive. My mother, my uncle, [and] several of my cousins. We’re pretty sure my grandfather was, but he’s since passed away. That’s only on my mom’s side of the family. That information, I think, is helpful.

Reactions to finding out it’s hereditary

Abigail J.: When people find out that their cancer was probably caused by their genes, they have no control over that. Do you find that helps people realize it’s not their fault?

Sue F.: It’s a mixed bag. I know for me it was a little bit of an a-ha, but not everybody gets that answer. Not every 33-year-old with breast cancer gets that. For them, they don’t get that, being able to know. Also, there can be a layer of guilt. There can be a layer of family dynamics. Sometimes the family dynamics that were already at play get heightened because of it.

It’s definitely a mixed bag. You’re not just at risk for one type of cancer, but it’s multiple cancers. It’s not always a relief. At the end of the day, people who are born with mutations always had the mutation. If they get to know it, at least they have a little bit of a chance of doing something potentially proactive about it.

Genetic testing

Abigail J.: Let’s just talk about how you find out you have a genetic mutation. You mentioned genetic counselors. I know there’s a couple of people that are typically involved when you want to find out if you have a genetic predisposition for cancer. I assume a doctor has to order a test.

Sue F.: Yes, that’s true.

Abigail J.: And then what happens?

Sue F.: There are a lot of different entrées into finding out that information. One thing we’re seeing more and more of is that people who are diagnosed with cancer — and especially if they’re diagnosed with, in the breast cancer realm, metastatic breast cancer — they may get tumor testing, and the tumor testing may suggest that there’s a mutation. We see that with prostate cancer as well.

That’s one way to [get to], “I may have an inherited mutation, and I should get genetic testing.” We recommend people talk to an expert in genetics because ordering the test is complicated. It’s not just one test anymore. As you were talking about, it’s not just BRCA1 and 2 anymore.

There’s at least 20-plus genes that have all been identified and associated with breast cancer, and then other genes associated with colorectal cancer. They now do panel testing. Being able to order the right test and appropriately interpret the results, you want some expertise.

Abigail J.: Is that a geneticist? Are you seeing a geneticist?

Sue F.: Or a genetic counselor. But also, there are oncologists who are highly trained in genetics. There are genetic nurses now. Really, there’s been an expansion of the amount of people who are able to provide that information up front, and then after someone gets a test result, also telling them what it means for themselves, what it means for their family, [and] who else in their family should now get that information.

The other thing — and this is the group we worry about — is there may be people who test negative, but there may be something still going on in that family. There may be clinical trials that they can join to look for other additional genes, or there may be further testing that would be appropriate for them. We want to make sure that just because someone gets a negative test doesn’t mean that they’re not seeing a genetics expert after that test result as well.

Direct-to-consumer genetic testing

Abigail J.: I know there’s been a whole lot of different genetic-type things in the news: genealogy things, 23andMe.

Sue F.: Yes. That’s the other thing I was going to mention.

Abigail J.: There’s other direct-to-consumer [tests]. Are those as reliable or as helpful as a test that is ordered by a doctor?

Sue F.: The short answer to that is no. Some of the tests, so like the 23andMe test, look for some of the more common mutations found in people of Ashkenazi Jewish descent there.

They, I think, are now reporting out some colorectal cancer mutations.

They’re testing just a small amount even in BRCA1 and 2. They’re not looking for these other genes, like ATM, PALB2, chek2, and these other genes that can have mutations. It’s not the same.

Even when the FDA said to 23andMe, “You can report the results of these tests to people,” it came with the caveat that if you do have testing that way, you should follow up with what they would call a “medical-grade test.” That would be from a lab. That is a doctor-ordered test.

Variant of unknown significance

Abigail J.: Sometimes when you have genetic testing, you see on the report a VUS, which is “variant of unknown significance.” What do you do with that?

Sue F.: Again, this is one of the reasons why we tell people, “Go see a genetics expert.” Unfortunately, we’ve seen healthcare professionals who didn’t have training in genetics report those as mutations to people.

A variant of uncertain or unknown significance, or VUS, is a frustrating result because genetic testing most of the time — especially for BRCA1 and 2, some of these newer genes a little less so — will be a, “Yes, you have a mutation,” or, “No, you don’t.”

Once in a while, you get this inconclusive test result. We haven’t tested enough people. We don’t know. It could be a gene change that’s the difference between two functioning genes, but they function just a little differently, but they still work, versus you have a mutation [that’s] causing cancer.

There’s really a need for expertise in those situations, because then from there, the best recommendations they make are based on your family history and your personal medical history. You really need someone who has that expertise and training to look at that and see which cancers are related.

There could be other testing for relatives that’s usually done as research to see if that VUS, or variant of uncertain significance, is tracking with the cancer in the family.

If everybody who’s had cancer in the family also has that same VUS, then that may be a little bit more evidence that this may be what they would call a pathogenic variant or one that’s cancer-causing.

There have been some research studies trying to classify variants, too. There’s a lot of researchers trying to figure out this frustrating problem. The US results are more common in some of these newer genes that have been newly discovered that they haven’t done as much testing on in some of these panels.

Genetics don’t guarantee you will get cancer

Abigail J.: Important to have an expert in your corner to help explain, even when you’re thinking about a test. Should you get the test? How do you interpret the test? Then you have the test, and it says there’s some genetic mutation. You have some predisposition towards cancer. That doesn’t mean that you’re going to get that cancer, right?

Sue F.: It doesn’t, but your risk may be very high, and it’s really important. The other thing that expanded panel testing has done for us is found all these genes, and they all have different risks.

It used to be that even BRCA1 and 2 were kind of lumped together, but the risks are a little different for the different cancers. BRCA1, you’re more likely to have ovarian cancer than BRCA2. BRCA2, you’re a little more likely to get pancreatic cancer than BRCA1.

They all are different, and the same is true for some of these other genes, like PALB2 and ATM. Fortunately, there are some guideline panels that look through the evidence every year and update those guidelines based on the gene.

It’s really important, too — and this is another reason to see an expert — to make sure that they recognize the gene you have may be different than BRCA1 or 2 and that they may come with a different set of guidelines and recommendations.

Resources provided by FORCE

Abigail J.: If there’s a person who is considering genetic testing, has had genetic testing, or has something that’s going on in the family, what can FORCE do for that particular person?

Sue F.: It depends on their circumstance. We have over 300 volunteers with different genes. Some have had cancer, and some have not. We match people by gene mutation, by their cancer diagnosis, their stage, their age if we can, and then geographically.

We really try and match people as best as we can to someone who’s had a similar situation so that they can talk to a peer who’s been through it. Then we connect them to personalized guidelines and information and even now clinical trials.

We have clinical trials that are embedded to our website based on the gene that someone has, because now there are clinical trials that are open to people with PALB2 or ATM.

To bring up a different topic, but [there are] people who don’t have inherited mutations but have acquired or somatic mutations that they found from tumor testing or from some of the biomarker testing looking at tumors.

We know that matching people to these types of specific clinical trials, they’re really looking for that needle in the haystack person, that subgroup of the larger group. It’s important to us to try and match people to clinical trials that they may be really uniquely suited to [in order to] actually fill enrollment and get those answers for themselves and future generations.

There’s a lot as far as the personalized information, the clinical trials, the support, the resources, [and] paying for care that we try and do and match according to someone’s situation, including their mutation.

Abigail J.: It’s such a labor of love to be able to give people that information.

Sue F.: Gratifying, too. It really is incredible — and I’m sure you know this — to be able to meet someone who is facing a challenge and be able to provide them with resources that can help them. What’s better than that?

Abigail J.: Absolutely. Thank you for being here today.

Sue F.: Thank you for inviting me.