Samuel Washington, MD, UCSF

Latest Bladder Cancer Research & Treatments

Dr. Samuel Washington is a urologist oncologist and assistant professor in-residence at the University of California, San Francisco. Dr. Washington’s research focuses on healthcare disparities.

In this conversation, he discusses how he became a doctor, the racial disparities in bladder cancer treatment and how to address those gaps.

- Name: Dr. Samuel Washington III, MD, MAS

- Roles:

- Assistant Professor of Urology, UCSF

- Goldberg-Benioff Endowed Professorship in Cancer Biology, USCF

- Education:

- 2007, UC Davis Bachelor of Science in Genetics, Minor in Latin

- 2012, UCSF Medical School

- 2018, UCSF Department of Urology, Residency

- 2019, UCSF Master’s Degree in Clinical Research

- 2020, UCSF Department of Urology, Urologic Oncology Fellowship

I commonly say no one’s intentionally contributing to disparities, but also very few of us are actively monitoring our own outcomes. We often see differences and attribute those entirely to the patient, [but] there could be things in our clinic or our clinical environment that we could impact.

- What drew you to practice medicine?

- How were you introduced to medicine?

- Underrepresentation in the number of Black physicians

- Muscle-invasive bladder cancer

- What does “who you are” mean in this context?

- Gaps and disparities in treatment

- What’s causing these differences in outcomes?

- What could be causing different treatment for White and Black patients with the same diagnosis?

- What cultural nuances affect the difference in treatment?

- Advice for patients

- What should patients do if they feel something isn’t fine when their doctor says it is?

- How to advocate for yourself with your doctor

- Other factors that can affect diagnosis and treatment

- It may take longer for older women, particularly women of color, to be diagnosed

- Psychological barrier of seeing blood in your urine

- If nothing’s changing, that’s a huge red flag that it’s not being addressed properly

- Addressing these issues

- Representation in clinical trials

- Upcoming research on bladder cancer

What drew you to practice medicine?

I was introduced to medicine when I was 7 years old, so I was one of those lucky ones that got early exposure. As a child, it was just the fascination of what people are doing. It hit all of the bases in terms of being a way to help people, but also a way to engage in an academic sense in something that was quite interesting.

You’ll see a lot of us, particularly those in academics, there is an intellectual component to what we do that drives our research. The research drives the questions, and how to improve patient care feeds into the research in and of itself. It becomes this kind of self-fulfilling, self-enriching cycle.

How were you introduced to medicine?

I grew up in Houston and a town outside of Houston called Sugar Land, Texas.

No one in my immediate family was in medicine, but my mother had a friend who was a cardiothoracic surgeon. She was always trying to get us exposed early to different professions, and thankfully she was in a job that allowed us to do that.

Once my family heard that, they kind of fostered that throughout. It became really trying to find ways to volunteer or get more exposure throughout my entire career up through college to understand what medicine looked like.

Underrepresentation in the number of Black physicians

I think even throughout medical school, we’re always told that Black patients are at greater risk of X, Y, or Z. It was just a way things were explained. We were supposed to memorize that these medicines work better in Black patients. Black patients were at greater risk of X, Y, and Z, and that’s just the way it is.

I think when you start to question that and understand the why, rather than just being presented with observations, it becomes a little bit more interesting. You see where the large gaps are. Then for me personally, we talk about Black men being at increased risk of prostate cancer, for example.

I’ve yet to see anything that could tell me what my personal risk is, myself being a Black man, a physician [with] higher education, formal education. The fact that we don’t have that, but we continue to talk about disparities just tells me there’s a lot we don’t know. Not much has been done to really flesh that out, generally speaking, within the field of urology. There’s a lot of area of improvement there that needs to be addressed.

Muscle-invasive bladder cancer

Disparities in the bladder cancer population

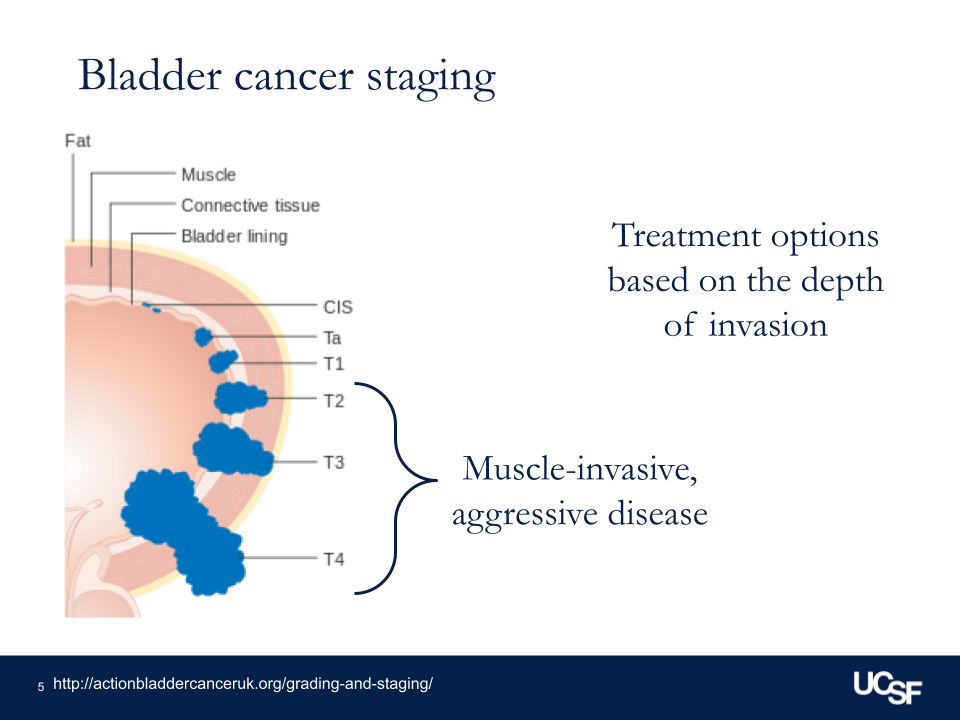

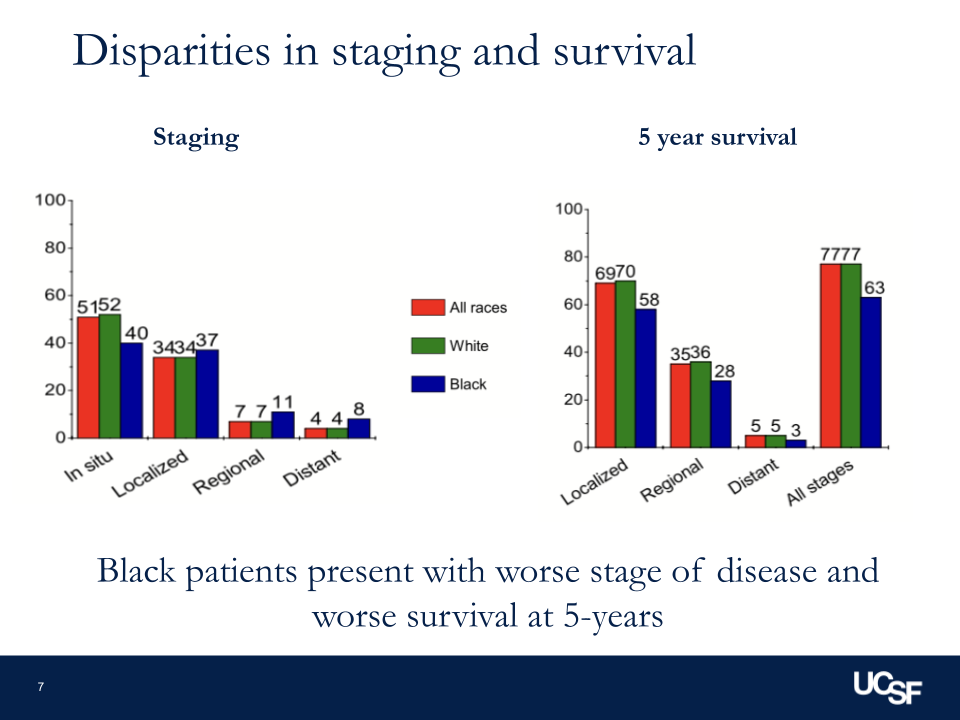

Overall, in general, we think of bladder cancer as either being muscle invasive, so growing into the muscle wall of the bladder — as I call the bladder kind of a balloon made out of muscle — versus non-muscle invasive, where it’s just on the surface or lining the inside of the bladder itself.

Our treatments are different, depending on which group you’re in. We know that for patients for whom the bladder cancer has grown into the muscle, across the board, people are not getting what our guidelines say they should be getting. Depending on the cohort you’re thinking about, half of people will get some guideline-concordant treatment.

There’s a question of guidelines being appropriate versus equitable, but we know that based on where you live, how far you are from a facility that treats bladder cancer routinely, [and] who you are are all things that can impact the quality of care and the type of care that you get. I think those are the key things that we see in bladder cancer that we hope to look at with some of our research.

What does “who you are” mean in this context?

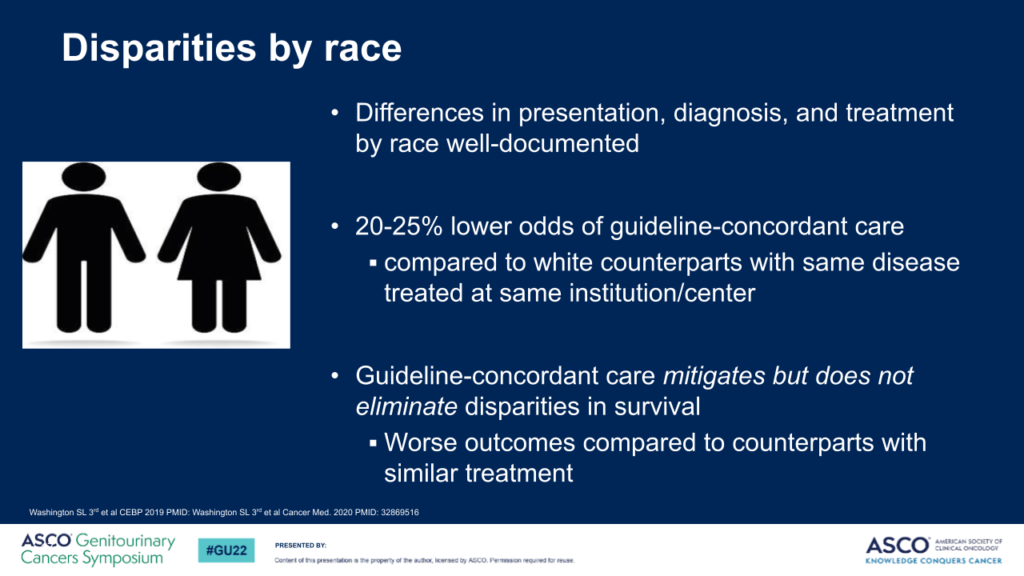

It can mean a lot of things. A lot of the research that I’ve looked at is around race as a social construct, so not just biology and seeing that there’s a biological difference between these peoples and that that is the cause of the differences and outcomes that we’re seeing.

[We’re looking at] how society is framing these people, Black versus White, insured versus not, educated versus not. All these different identities impact one another to lead to these outcomes that we’re seeing that are differences between groups.

How many bladder cancer patients have muscle-invasive cancer?

When we look at the overall cohort, I would say, depending on what you’re looking at, 25%, around there, 20%.

More aggressive treatment and worse prognosis for muscle-invasive cancer

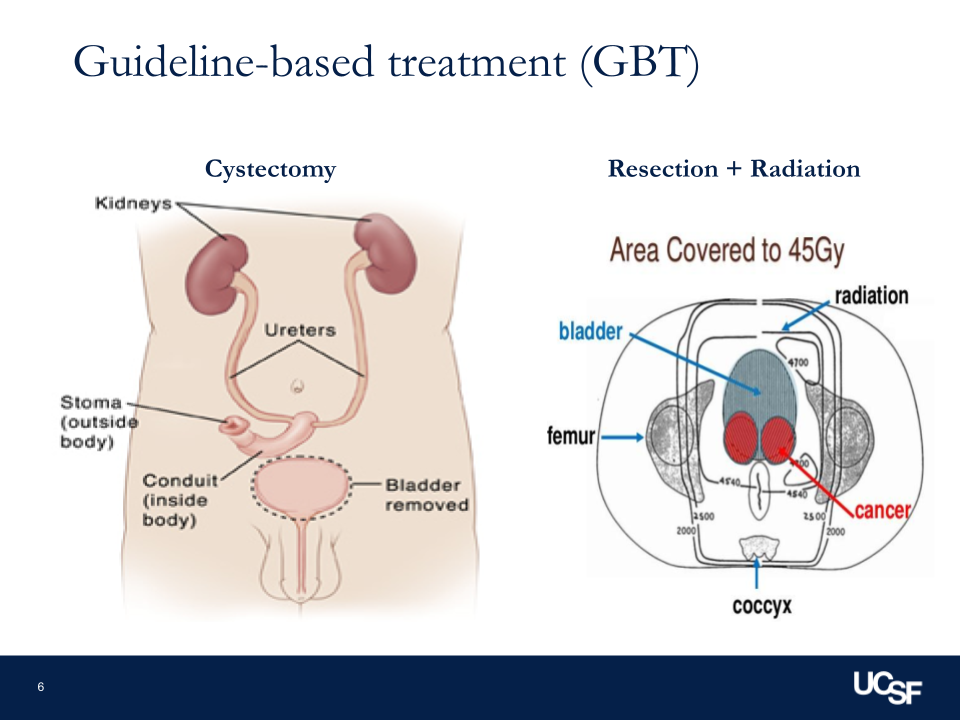

If we are talking about bladder cancer that’s grown into the muscle, that’s muscle invasive, the gold standard for the last 20, 30 years has been removal of the bladder and rerouting the urine through one of many different ways.

What has been increasing in interest recently is trimodal therapy, which means using 3 different methods to preserve the bladder but still treat that aggressive bladder cancer. We know the type of treatment you get [and] how long it takes for you to get that treatment are all factors that impact your survival after diagnosis.

Recommended guidelines for muscle-invasive bladder cancer

I’d say broadly for muscle-invasive disease, our two options currently would either be radical cystectomy, which means surgery to remove the prostate and bladder and reroute the urine, versus trimodal therapy. It’s a combination of radiation, chemotherapy, and scraping out any residual cancer there may be to treat the cancer but leave the bladder in place.

As part of that workup and evaluation, you should be getting scans to understand if all the cancer is just in the bladder or if it is moved outside the bladder. As part of that, you should be talking with a medical oncologist to understand if you can get chemotherapy beforehand or after to help treat the cancer in any small cells that may be in the bladder or outside. If those things aren’t happening, if you’re not getting guideline-concordant care, then we know we’re chipping away at your survival risk over time.

What other treatment could they be getting, and how does that affect the outcome?

What that means is if patients aren’t getting treatment within 90 days of their diagnosis, if they’re not getting guideline-concordant care, they’re getting care that may not cure or control the cancer. Functionally, what that means is they’re going to be at higher risk of the cancer spreading [and] higher risk of eventual mortality or death caused by the bladder cancer, which is what we want to avoid.

Gaps and disparities in treatment

What are the current gaps in guideline-based treatment?

Guidelines in general are a set of recommendations by our overarching governing body telling us, based on the most updated literature in research and the consensus statement of experts, what this patient should have based on the type of cancer or disease that they have.

Those are what our guidelines are. It’s taking the mystery out of medicine, but it’s really kind of an algorithm. We find where these people fit in terms of the cancer staging and characteristics. Then we look at the guidelines, and they tell us what should offer the best outcomes for them.

Major governing bodies

There are a few — there’s our National American Urological Association, there’s the NCCN (National Comprehensive Cancer Network) — that are overarching organizations that accrue recommendations from experts in the literature to give evidence-based recommendations of what we should do.

Frequency of updates

Almost every year or every few years, particularly if there’s a new clinical trial or a new change that really changes the way that we practice in terms of a new study or a new drug.

Results of studies on treatment impact by race

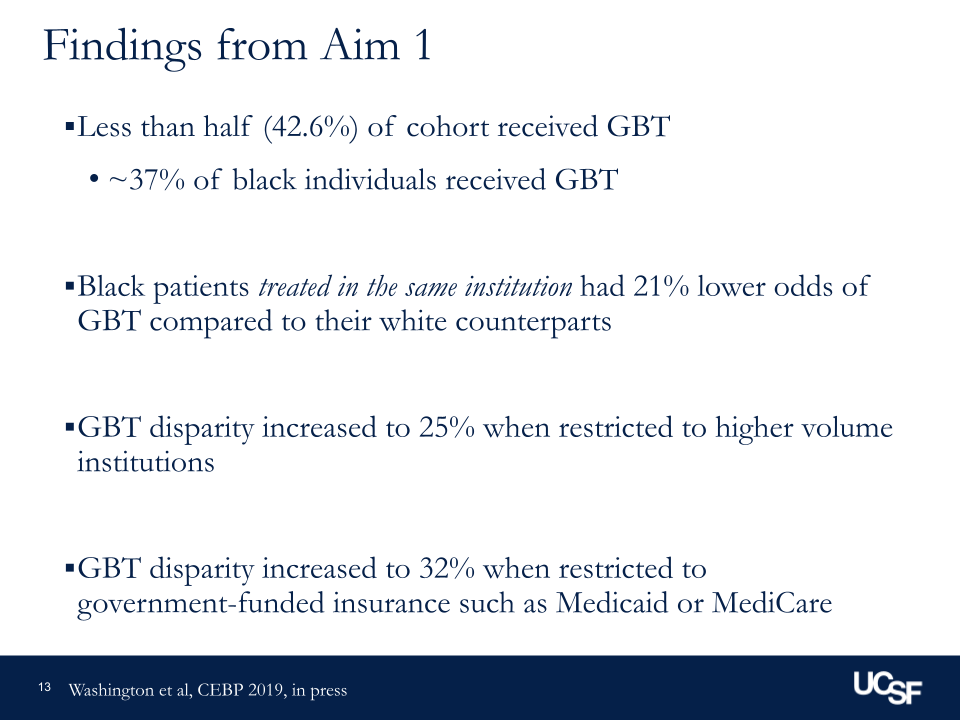

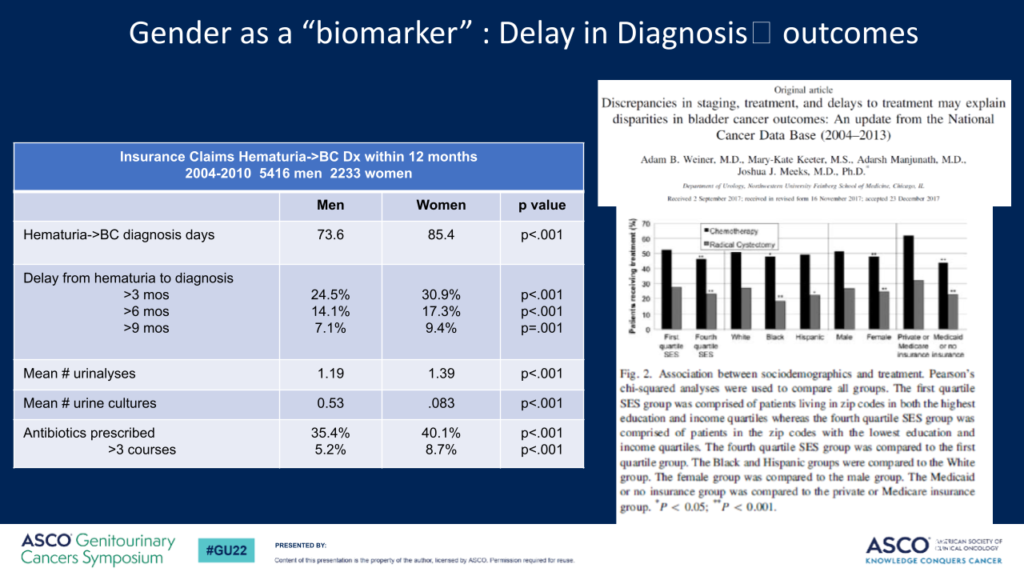

From a study that we did using National Cancer registry data, we saw that when you start looking at not only disease characteristics but other non-clinical factors — so patients’ education, their insurance, so on and so forth — we saw that Black patients had 20 to 25% decreased odds or likelihood of getting guideline-concordant care compared to white counterparts with the same disease treated in the same location.

You start to see differences like that across different groups. The issue is that it’s not uniform, so each group has a different relationship or association that we’re seeing there, and we don’t have a clear understanding of why that is.

What’s causing these differences in outcomes?

It’s a good question. Thankfully, there are large studies happening now focused on patient-reported outcomes, so what’s going on from the patient perspective. I would say what’s not happening now is what’s happening at the physician or the facility level.

We have cancer registry data that is collected, organized, and reviewed by different research groups, but it doesn’t really tell us in a way that gives us feedback how our practice is performing. It doesn’t tell us, are there disparities at our practice? That requires a large infrastructure of a practice or an institution to be able to do that, and that’s not present everywhere yet.

What could be causing different treatment for White and Black patients with the same diagnosis?

Thankfully, over the last few years, we started to address structural issues related to differences in care, structural racism, [and] institutional barriers to care for some people. We’ve seen this come into play even with telehealth. Functionally, patients need to have a smartphone or a laptop in order to participate in telehealth. If you don’t have those, [if] you don’t have access to broadband, or reliable Internet, you can’t have the same outcomes. We’re not measuring any of this stuff.

We also have to take a look at the providers themselves. I commonly say no one’s intentionally contributing to disparities, but also very few of us are actively monitoring our own outcomes. We often see differences and attribute those entirely to the patient, [but] there could be things in our clinic or our clinical environment that we could impact:

- The educational materials that we use and the required health literacy level for that.

- How we provide access to care for different patients.

- Are there things that could help patients in terms of transportation, social work, and so on and so forth?

Those things are not commonly measured at the same level that we monitor cancer diagnoses.

What cultural nuances affect the difference in treatment?

I think part of it is an understandable, and I would argue justified, mistrust in the healthcare system, given the history that we’ve had in the approach that medicine has used to justify some societal pressures and patterns.

I think what it comes down to often for patients that see me is for them, there is a shared life experience that we have that provides more comfort. That doesn’t mean that other practitioners that don’t look like them will not offer good care, but it does potentially provide a level of comfort that is not something that they’ve encountered before.

Instances of that that we’ve seen would even be prostate cancer screening, for example, in barbershops or in churches, bringing information to the patients, rather than us in our sterile clinical environment telling patients what they should have.

It does impact patients’ perception of care. We’ve seen how it impacts patients’ reluctance with new medications [and] adherence to different protocols. It does have an impact. It’s just that we haven’t measured it all that well thus far.

Advice for patients

What are some tips for patients?

I would say, generally speaking, if you see blood in your urine at any point, I would ask that that be worked up. That could be either just repeating a test, but oftentimes if you’re seeing blood in your urine, you need to see a urologist.

That’s kind of right up front in terms of not missing a timely diagnosis evaluation of potential cancer. If you have cancer that’s invading into the muscle, it’s worth asking, “Can I speak to someone that treats this routinely?” Because all urologists do not treat everything routinely.

I think that it becomes an issue when you see someone who does bladder cancer management as their primary focus versus someone who treats 1 or 2 bladder cancer patients a year. Both are trying to help you, but the comfort [and] the level of expertise in the nuanced information may be different between those 2 providers.

What should patients do if they feel something isn’t fine when their doctor says it is?

I think it’s worth asking, “Why is it fine? What would make it not fine?” I just have to remind people that everyone’s doing this already. I commonly get questions about negative tests [and] about positive tests. People are asking for more information. They’re looking for more information.

I think when people are worried about upsetting their doctor or getting the doctor mad for asking too many questions, that’s not really a thing. That’s already happening. I feel like people don’t understand that it’s happening all around us all the time in general anyway. It’s much more common than people would guess.

How to advocate for yourself with your doctor

I’d say the key things that I try to tell everyone are you need to feel comfortable with what’s happening. If you’re not feeling comfortable with the provider or the information, you need to feel comfortable.

If that means asking more questions of that provider, if it means finding other ways to get more information like the Bladder Cancer Advocacy Network, if it means going through support groups or peer groups for others who’ve been down that road. Getting more information is key so you feel comfortable.

Sometimes that’s a second opinion. Sometimes that’s just, “Hey, can I ask this doctor a few questions in an informal setting?” At the end of the day, you have to feel comfortable, so whatever it takes for that, because people are already doing it.

Other factors that can affect diagnosis and treatment

Generational differences in comfort level at the doctor

Depending on the generation, people’s background, [and] their comfort with health literature and all of the jargon we use, there’s different levels of how comfortable people will feel asking questions of the provider or asking for a second opinion in general. But that’s always an option. It’s covered by most insurances, and there are ways to ask questions in a manner that will not alienate your provider if that’s a concern.

It may take longer for older women, particularly women of color, to be diagnosed

I’d say women who are found to have repeated tests of blood in the urine or they see blood in the urine, sometimes these can be attributed to recurrent urinary tract infections. Whether or not there’s a positive urine culture [or] urine test showing bacteria, they will be routinely treated with antibiotics.

But what is missing is the workup to make sure that it’s not a cancer that’s hiding there and causing the bleeding. That can lead to delays as people get treated with antibiotics, and you don’t see any change in the symptoms. It’s because we’re not treating it correctly.

Particularly in those settings, particularly in women who are past menopause, postmenopausal bleeding is most certainly a concern to make sure we don’t miss a cancer diagnosis or something else that may be going on.

Psychological barrier of seeing blood in your urine

I would say I would feel incredibly worried if I saw blood in my urine. It takes a little bit of time and a little bit of effort to get past that and understand that is not something that’s normal.

I always tell people I would rather you ask the question, get it evaluated, and catch something early or it be nothing than the other way around, delay things, and miss a timely diagnosis.

If nothing’s changing, that’s a huge red flag that it’s not being addressed properly

I tell everyone that we are just humans who practice medicine. We are not infallible. We don’t know everything. It goes against the idea of a physician knowing everything. There’s a lot we don’t know.

I think at the end of the day, you need to make sure you know if there’s cancer or if there’s something else there. Understanding that a workup needs to be done and if you’re trying things and there’s no change, it’s time to reevaluate things.

Addressing these issues

What can we do to comprehensively address the inequity?

I think there are a few different facets to this. What is done currently, I would say, in some of the patients that I even see, when they are not getting satisfactory answers from their provider, they reach out to friends, or they ask, “Hey, can I see your doctor? Hey, do you know a doctor? Can I talk with that person?”

That happens to me. It happens [to] my colleagues all the time. That’s a way to get more information. I think what needs to be happening kind of at a systems level is checks. We need to monitor these things. What is happening with patients? Are we seeing differences in outcomes in our own practice?

I think intuitively all providers will say, “No, there’s not,” but we know that that’s not true. It’s not intentional, but no one’s looking. I think that when it comes to advocacy groups, advocating to be part of these research projects [and] focusing on projects that are relevant and pertinent to the patient, rather than just the investigator or the clinician, is important.

I think when it comes on a regulatory standpoint, it’s very tough to pull that nuance into regulations without cherry-picking happening, so people kind of selecting or ignoring specific patients to buffer or pad their outcomes. There are a few different ways for us to improve it at different levels. At the end of the day, I think this is a multi-level issue that’s not just the patients. It’s not just providers, not just system.

Representation in clinical trials

There’s a whole different discussion of how clinical trials don’t reflect the population. How can we take information from a clinical trial and apply it to a population that wasn’t included in the study?

I would argue my goal would be to find patients and treat them so patients don’t need a clinical trial. Their disease hasn’t progressed to the point where they need that. That’s a goal that I have and others have, but it’s a little bit different than the recent push to include representation in drug clinical trials, for example.

Have you had Black patients thankful to have a doctor who looks like them?

I get it not infrequently that a Black patient will just say that they’re happy to see me or someone that looks like me. It just reminds me that of the urologic workforce, it’s less than 3% of us, for all of urology, that are African-American [or] Black. [It’s] a much smaller percentage when you start to chip away and look at different subspecialties.

Again, it’s a level of comfort and shared lived experience that some patients have. Multiple patients or just advocates come up to me and just say they’re glad that there’s someone that looks like them. They’ve never met a Black urologist or a Black urologic oncologist, and I think that matters.

It may not be important for everyone, but I think for some patients, it is a game changer in their comfort with the care that they’re getting. It has absolutely nothing to do with the quality of the care I’m actually providing.

What can treatment providers do to make their patients more comfortable when they don’t have shared lived experiences?

I think embracing shared decision-making in general. It’s become part of our guidelines. Everyone says it should happen. Understanding patients’ level of comfort with our jargon, understanding if patients have questions, asking them what other questions they have, [and] making sure that they truly understand what’s going on are little things that we can do.

When you start to see patients who are lost to follow-up or missing appointments, simply asking them, “Is there something that can be helped? Or what barriers are you dealing with?”

[These] are questions that are not part of our questionnaires. They are not part of our clinical algorithm, but they’re very impactful for the care for the patient. I think asking those questions, which only takes another minute or two, can be hugely impactful.

Upcoming research on bladder cancer

I’d say that there’s a lot of ongoing research. I would tell patients who are interested in more information about bladder cancer, the treatments, support groups, and ongoing research, there are many outlets out there.

Bladder Cancer Advocacy Network is one that is focused entirely on this. Also, just asking your provider, “Are there resources here that I can look at? Are there clinical trials or support groups or information?” [That’s] another thing that I would like to get across.

More Oncologist Interviews

Dr. Christopher Weight, M.D.

Role: Center Director Urologic Oncology

Focus: Urological oncology, including kidney, prostate, bladder cancers

Provider: Cleveland Clinic

...

Doug Blayney, MD

Oncologist: Specializing in breast cancer | HER2, Estrogen+, Triple Negative, Lumpectomy vs. Mastectomy

Experience: 30+ years

Institution: Stanford Medical

...

Dr. Kenneth Biehl, M.D.

Role: Radiation oncologist

Focus: Specializing in radiation therapy treatment for all cancers | Brachytherapy, External Beam Radiation Treatment, IMRT

Provider: Salinas Valley Memorial Health

...

James Berenson, MD

Oncologist: Specializing in myeloma and other blood and bone disorders

Experience: 35+ years

Institution: Berenson Cancer Center

...