Pathologists: The Unseen Cancer Doctors of Your Medical Team

An interview with Kamran Mirza, MD, PhD

Pathologists are the cancer doctors you’ve likely never met. They are the doctors that evaluate patient tissues and cells to provide a diagnostic report. That report is then used by the oncologists to build a treatment plan. Pathologists play a huge role in cancer care yet very few patients have the full picture of what they do.

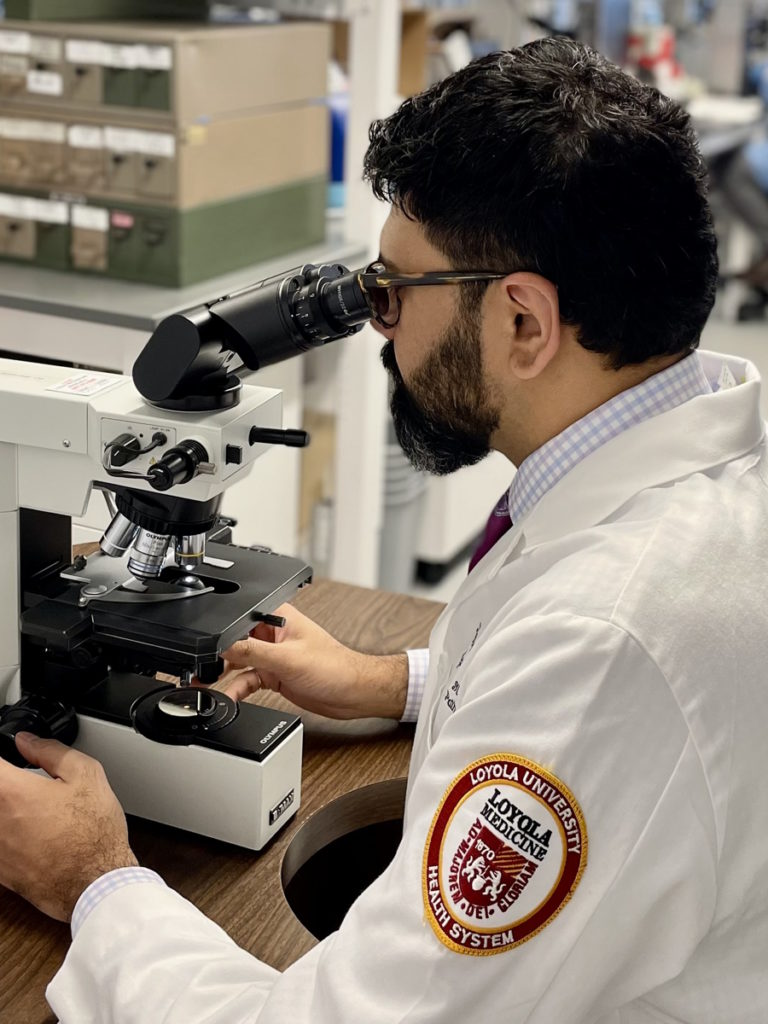

Dr. Kamran Mirza is a Hematopathologist at Loyola University Medical Center. He is specially trained to diagnose hematologic diseases. Even though most patients never see him, he takes each case personally.

“I almost always ask myself, ‘If this was my mom, what would I do?” Dr. Mirza explains. “If this was my own specimen, what would I do?’ Whatever the answer is is what I do. It becomes pretty clear.”

He explains more about the role of pathologists, what happens from test to diagnosis, why there may be delays in getting results, and how patients can better understand their own pathology reports.

How to Read Your Cancer Pathology Report: A Pathologist Explains

This interview has been edited for clarity. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider for treatment decisions.

Introduction

I’m a hematopathologist. I’m originally from Pakistan. I grew up in England and completed medical school in Pakistan before moving to the United States. I’ve been in Chicago pretty much most of my adult life.

I’m a husband [and] a girl dad of three. Most of my free time is spent with the girls. They’re all different ages so completely different activities. My daughters range from 18 to 8. It’s a wonderful world. All three of them are so different — different personalities, different takes on life. It’s just amazing to see them grow up.

I love art and art history. I used to direct plays in college.

How did you get into medicine?

In Pakistan, we don’t have the equivalent of college. We directly apply for university. You don’t really have a four-year undergrad, basically.

When I was finishing high school in Pakistan, I decided to apply to two schools. One was an art school for architecture and one was a medical school.

My parents are both doctors and, classic South Asian, I thought, “I don’t want to become a doctor.” All my life, I thought, “I’m not going to become a doctor because it’ll seem too much like I’m following in my parents’ footsteps.” They actually helped convince me. “You shouldn’t do medicine. Think about art. Think about architecture.”

But I really loved medicine. I loved biology. I loved thinking about human disease. I was 18 and was going to let fate decide. There’s no way I’m going to get into both schools, but I did so that didn’t help. Then I made a conscious, informed decision to go to medical school and I don’t regret it.

I think that there is, I would say, an artsy side to me and it actually ties back into pathology. It’s a very visual field of medicine. I almost always think about the fact that in pathology, I blended my love for art and for science together.

What do you mean by pathology as an art?

A pathologist is a physician that deals with the diagnosis of disease. If you have ever been to a doctor, you had another doctor in that team, and that doctor is a pathologist.

We work behind the scenes mostly. We have little, if any, direct patient interaction, although there are some pathologists that do see patients. We work in laboratories and in departments [that are] usually in the basement.

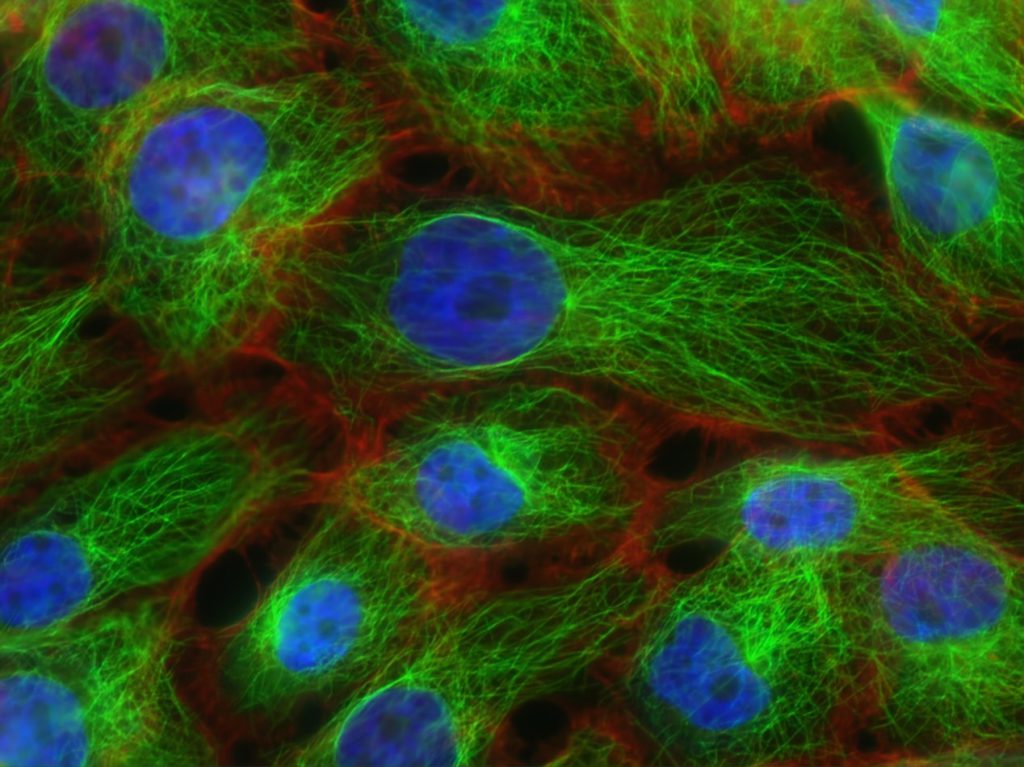

We deal with the diagnosis of human disease [by] looking at tissues or specimens from humans. Our work is at the cellular level. We look at the specifics of what your cells are telling us. Are the cells telling us that the cells are normal or are they telling us that there’s something happening to them? We interpret that.

It’s actually very intimate if you think about it. If a person has a mass or a lesion that’s biopsied, it’s a very vulnerable position that there’s a physician who’s actually looking at the cells. While the patients aren’t aware of that interaction, obviously, the physician-pathologist on the other side is.

The human body is beautiful in its symmetry sometimes and it’s the way the cells are [and] the types of features the cells have. Some cells have extensions, some cells have big nuclei, [and] some cells have small nuclei.

While, scientifically, I never describe what I see as beautiful because that would probably be disrespectful in case it’s horrible cancer, from an artistic perspective, looking at what the human body looks like on a cellular level or a genetic level is beautiful, really.

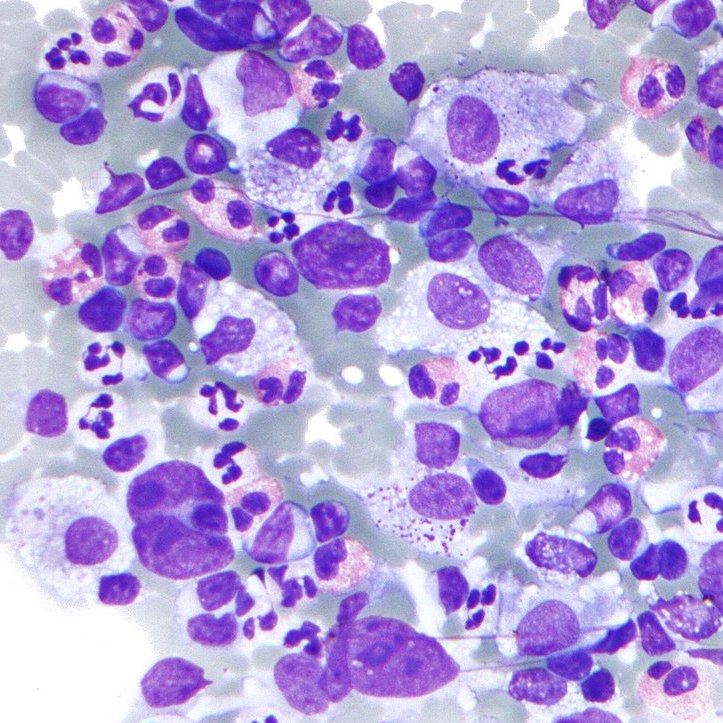

It’s just a wonderful tapestry of different types of cells. On a day-to-day basis, I’m looking at blood cells on a smear. I’m looking at bone marrow cells. I’m a hematopathologist so that’s a diagnosis of leukemia and lymphoma. I think that there’s a visual beauty to diagnosis, which is part of every patient’s disease journey.

What made you want to be a pathologist?

What drew me to pathology was an interesting decision. It wasn’t clear-cut. Pathology isn’t really well-exposed as a career [for] medical students. They study the pathology of disease as part of their pre-clinical curriculum, but they don’t really see what a pathologist does in practice. It’s not front and center within the choices of what type of doctor you’re going to become.

I loved interacting with patients. I thrived on it. My friends were confused. “Why are you choosing a life where you’re not going to see patients as often directly?”

After having seen pathology, every day is so different. I see so many patients on my microscope. Multiple biopsies, multiple specimens, multiple laboratory tests. I can affect a lot of patients hopefully with the right diagnosis.

There is beauty in being able to demystify [the] human disease. It’s the gold standard. Everyone else in the diagnostic process is kind of guessing. Patients present with a particular set of symptoms and signs. More often than not, there’s a differential diagnosis, but the pathologist is the one who looks at the tissue and can give you the definitive diagnosis.

Being able to demystify the disease really intrigued me and think about, intellectually, what’s happening on a cellular level that is making patients sick and then correlating it with how the patients present it.

We are clinicians. We are thinking with the clinical part of our brains, but we’re looking at tissues and interpreting what the tissues are telling us. That really drew me into it.

I’m a specialist who’s part of a patient’s healthcare team, but my specialty is the diagnosis of the disease. I think that that’s an incredibly important step because I think it’s the first step in the journey of healing.

How long do pathology tests take?

Often, patients think that their tissue has gone into this black box. Actually, many of my physician colleagues don’t really know what’s happening in the pathology lab, too. But rest assured that once your sample goes away from your site, it’s being taken care of to the highest degree of care.

Whether it be blood, bone marrow, or a different type of biopsy, there are certain similarities in the ways we process specimens to be able to interpret them. Some will be faster, some will be slower, and it really does depend on what type of information we’re looking for.

For example, a blood specimen is a relatively simple biopsy, if you think about it. It’s just a needle prick, you get the blood, and then we can do several things to it. We can smear it on a slide and look at the cells. We can count the cells. We can see if the cells are looking normal or abnormal.

In our clinical laboratories, there are medical laboratory scientists that are working with these samples to make sure that the numbers are okay and everything looks normal. If whoever is looking at those cells, sees something abnormal, then those are flagged for review by a physician, which is a pathologist.

As a hematopathologist, I get to see all the flagged smears that have probably something abnormal. Then I have to triage and ask, “Is this abnormal in that it’s malignant? Is it abnormal in that it’s reactive?”

If a six-year-old has a fever and a high white count, who will tell their physician whether this is an infection or leukemia? The answer is coming from the laboratory. Because the presentation will be very similar.

The patient might have a fever [and] feel poorly, and the white count will be increased. But then we have to look at the cells and say, “Are they malignant cells or are they reactive cells?” It’s an incredibly important and major responsibility to get that call correct.

If a patient has an infection, there is an increase in cells; it’s a reaction to the infection. If it’s a bacterial infection in the blood, there’ll be lots of neutrophils, which is a particular type of cell.

If I see tons of neutrophils as the reason for the increase in the white cell count, my guess will be, “Okay, this is likely a reaction to the patient’s infection.” My recommendation would be [to] check out the microbiology studies or see if the patient has an infection.

They could be lymphocytes, which is a completely different kind of thinking about what type of infection it could be. They could be monocytes.

They could be immature cells. When we’re going to immature cells in the degree of their maturation, that’s where we can start wondering about, “Okay, this may not be a reaction. This could be a malignancy that’s causing the increase in the cells.”

Things like that can be quick. Depending on how long it takes for the specimen to get to the laboratory, we can report certain things within an hour.

How are pathology tests processed?

When we take tissue from the human body, whether this be in surgery, a biopsy, or what have you, that material needs to be processed in order for it to then come as a slide to the microscope, and that usually involves some element of fixation.

Fresh tissue will start degrading very quickly so we have to immediately take the tissue and put it in a fixative so that the cellular biology is frozen for us to be able to process it. Normally, that’s formalin fixation, even though there are multiple other types of fixative.

We process this tissue, we fix it in formalin, and then we embed it in wax, which is paraffin. We cut ten sections of it and those sections come on our slides. That process can take a few hours. The fixation takes a few hours, depending on what time it is. It could be overnight. We’re now looking at going into the next day.

After the tissue is on the slide, it’s transparent so we have to put a stain on it to see what the tissue [looks] like. That takes a couple more hours. Then based on what we see, it could be an instantaneous answer that everything looks normal or it could require additional studies.

If I take the example of lymphoma, it’s not enough to just say it’s lymphoma. We have to figure out if it’s B cell, T cell, or Hodgkin lymphoma. Then within that, are there certain markers that we know will give a better prognosis or a worse prognosis? This could involve looking at the genes, looking at mutations, looking at chromosomes, and this can take from a couple of days to weeks.

That, naturally, can be very frustrating for the patient who is waiting for that answer. Rest assured that we are very aware of the fact that delays cause more stress.

If it’s taking a long time, we are in the process of getting the correct answers so that the hem-onc (hematologist-oncologist) can consider the state of diagnosis and prognosis so they can think about therapy appropriately.

Rest assured that we are very aware of the fact that delays cause more stress.

It’s nice to be able to get a preliminary answer and we often do that. I’ll pick up the phone, call the hem-onc, and say, “Okay, it’s looking malignant so this will take some time.” Then it’s up to them to triage depending on how the patient is. Are they calm or are they very stressed out? That’s the side we don’t deal with because we don’t see patients directly.

More often than not, if there [are] any surprise malignant diagnoses, I call my patient-facing colleagues and give them a heads up that this is happening so they can temper the expectation of how long it’ll take.

Different wait times for pathology results

The larger academic centers will have a pretty robust laboratory where not only will the tissue processing happen on-site but, most likely, everything can be done right there.

There are some hospitals that are academic and they can do much of it on-site but maybe 10% is sent to a bigger laboratory. These large conglomerate laboratories do testing for other labs as well.

Smaller community hospitals, which are great hospitals, may not be able to sustain large pathology departments. They will usually break up the situation such that they’ll be able to offer immediate testing on-site. Those are the decisions that need to be yes/no, immediately enacted. If it’s tissue processing, etc., then sometimes they do have off-site partners or maybe they have a laboratory that caters to different hospitals so that model also exists.

For the patient, you don’t have to worry about exactly what model it is because I hope that it will be excellent pathology care, but it does factor into delays. If a tissue comes out and has to be fixed but it has to go off-site, then there’ll be a transportation delay.

However, with electronic records, the report comes out immediately and with the Cures Act, patients sometimes see the report now even without their physician seeing it. The reporting is instantaneous, but the amount of time that it takes from the biopsy to us being able to give an answer is variable.

I’ve been a patient, too. In my mind, the second the tissue comes out of the human body is when the clock starts. But the reality is the pathologist may not actually even get the tissue for 12 hours or something. Our clock in the laboratory is different.

There are lots of necessary but unfortunate delays that have to happen for things to happen appropriately, which cause delays and frustration. The important thing is that you get the right answer.

You don’t want to force it to be too quick and get the wrong answer because that’s not right. Getting the right answer is the first step in healing.

Patients seeing the results before a doctor is notified

The diagnostic information of a patient is the patient’s property. If I’m writing a diagnosis for the patient, they have [the] full right to know that immediately. There doesn’t need to be any filter through which they get that information.

But there are many caveats to this.

Who is the patient we’re talking about? What is the patient’s baseline understanding of the disease that they’re talking about? What is their baseline understanding of STEM in general? How much science do they possibly know? Maybe they don’t have any idea about molecular jargon. This is very difficult for them to see a report.

A patient presents with suspected leukemia or lymphoma. They go to a hematologist-oncologist and that individual orders a test for a biopsy that comes to me as a consultant.

When I’m consulting, I have two stakeholders. The patient is my number one stakeholder, but number two is the physician who sent me that consultation. My report is written in jargon in response to the consultation that I got from another physician.

Now, a lot of stuff can get lost in translation in this interaction because it’s a conversation between two physicians, but it is about a patient’s material. The patient will get that result immediately. They might get it when their hematologist is busy and doesn’t have time to look at that notification but that notification went out to them and also to the patient.

The patient opened it and is reading words like acute leukemia cytogenetics, looking at mitosis, malignancy, and neoplasia. There is no filter.

The physician could have filtered that information, sat this patient down, and said, “All right, we’re going to have a conversation. Take a sip of water. We have the results back. This is what this is. This is what this means.”

Like in any situation, there are pros and cons. I’m fully for the fact that patients, [as] the owners of their diagnostic information, should get access immediately. The caveat is that if it’s a completely normal-looking result, then that’s one thing.

What about people who are getting cancer diagnoses? They look and say, “Oh, carcinoma.” Many people understand carcinoma or lymphoma. There’ll be words that we use in our classification that patients may not understand or may not have even heard of.

By and large, I think it’s excellent that patients are getting that information, but I do think that it has caused frustration on the part of both the patient and the patient-facing physician. There could be situations where things fall through the cracks and that’s not ideal.

It’s like writing an email or a text. You don’t know how the person reading it is going to interpret it. Do I put a period? Do I put an exclamation mark? The tone of how I’m speaking is different when I’m speaking in person and it may be quite stressful to read it.

I’ve considered it and I think many people do this. They write a note to the patient at the bottom of the report, for example. I could do that. I could say something like, “To the patient, this report is indicating that there is a malignant process occurring in your blood. This process is called leukemia. It is acute leukemia.”

Immediately, there might be 10 words in the sentence that I don’t know if the patient is understanding or not. Do I do a whole thesis? “Normally there are three types of nuclear cells in the blood that we look for and in this report, we’re seeing that one cell type has gone rogue and is taking over. This is a malignancy called leukemia. Please wait till your hematologist gives you the information about what this means, what the next steps will be, etc.”

That’s simple enough but even that, I would say, is full of caveats. Am I saying this in an upbeat tone? Am I saying it in a depressing tone? Is this a death sentence? We all know that everyone is stressed out about these things and understandably so.

There are some centers where you can go and see your material on a multi-headed microscope where you can sit with the pathologist. They review your material and show you what that is. I think that that’s incredible. It’s brilliant.

Why not see the material with your physician that’s looking at it? If there are questions that you have, for example. It’s possible that some people don’t want to see it and that’s fine.

One of the pathologists who is seeing patients titled a very interesting paper: Please Help Me See the Dragon I am Slaying. Basically, for them, they were helping their patients see the dragon that they were going to slay. This is the obstacle and now you’re going to try and overcome it. Some people want to see the dragon, some people don’t, but understanding more about their disease process, if a patient is interested, helps them.

What happens when pathologists are done with a result?

Fridays can be very tricky. There [are] actually papers published about Friday night leukemias. There is data to show that if patients are feeling sick or poorly during the week but they can still push along — let’s assume they have a blood cancer called leukemia and it’s making them sick — typically, they will push along until Friday because they don’t want to go during the middle of the week. They’ll come on Friday because they’ll think, “Okay, whatever it is, we’ll have the weekend to deal with it.”

Friday night leukemia, in my world, is a reality. When I’m packing up on Friday evening to go home, I always have this in the back of my mind because it’s possible that, at that particular point, there might be a patient who waited all week, showed up, and by the time it’s Friday evening, the laboratory is getting leukemia. It doesn’t happen that often, but you can understand anecdotally that that could possibly happen.

If I get a Friday night leukemia, I will call the person who ordered the test and let them know. The trickiness is that depending on what type of report it is, the patient might know, too.

»MORE: Leukemia patient stories

If there was an opt-in [or] opt-out, that would be ideal for the patient but the jargon I have to use has to be scientific. The words being used and their classification system will be looked at by insurance companies, by people auditing diagnoses that, God forbid if I make a mistake or if I ever get sued, people will come back and say, “Okay, what did he say?”

A part of the report, I can’t change. Even if I wanted to make it more friendly for my patient, that portion will stay the same.

If the diagnosis is acute myeloid leukemia, those are the words I have to use. Because my colleagues who’ve given me this consultation know what to do with that information. I can’t call it malignancy of neoplastic white blood cells. It’s just describing it, but the words are the words.

The conversation is nuanced, let’s put it that way. I have heard physicians telling pathology members, “If you’re ready with a report on Friday, let me know before you release it.” I think that’s a totally reasonable request. I’ll page them and say, “Okay, I’m about to release it,” just so that they know because they will probably get called by the patient before I’m leaving for home.

My job is done. I’ve done what I needed to do. In that sense, I have to be respectful of my colleagues, but ultimately, the priority number one is my patients.

It’s important because patients getting that information directly also allows them to consider things like second opinions [and] to share information with other people. Could that help the whole process of disease diagnosis and perhaps correct diagnosis?

No human is perfect so it’s a nuanced conversation. It’s important for patients to know that there are incredibly caring physicians on the other side who are taking care of this. They’re acting mostly as consultants to other physicians, but they’re still considering the patient first.

I’m thinking about genetic testing, [the] costs of testing, [and] not ordering too many things on this tissue to keep the cost low but to get the right information. There [are] so many things that I’m doing as your pathologist-physician that you just don’t even know about. Maybe it’s a good feeling that you know that, “Somewhere in the laboratory, there’s a physician who’s also taking care of me and I don’t even know about them.”

Conversation between the pathologist & the patient-facing physician

They’re looking to us to really give them the diagnosis. But I do appreciate that it’s a conversation, this interaction that we have, and that’s where multidisciplinary teams come in.

Breast cancer is not just breast cancer. The pathologist, the breast oncologist, the radiation oncologist, the pharmacist, the advanced practice provider — everybody has to get together and come up with a plan.

It starts with some basic things. Cancer: yes or no? Does it express certain markers? What category? Clinically, what type of performance status does this individual have?

It’s a team effort. There could be some back and forth. If I’m seeing some unusual cells, I might call the physician seeing the patient and say, “Is there an infection? Are there increased lymph nodes?” This data is in the electronic record, but sometimes, if the patient just presented, it’s not in their record yet so I’m already making up my mind with a few things.

I’m thinking about the patient’s age, what they’re presenting with, and interpreting what I’m seeing in that context. It’s incredibly important. If it’s a 94-year-old woman who’s presenting with a particular symptom, it might be completely different from a 17-year-old who is presenting with a similar symptom.

There’s lots of collaboration and lots of conversation between the physician who sees the patient and me. I love that interaction because it only helps the patient for us to be more communicative.

There have been times [when] they’ve interacted with us and asked questions like, “Oh, that’s a surprise. Did you consider this?” We’ll be say, “Yeah, we definitely considered it, but it is a surprise diagnosis.” Or they were thinking it’s completely benign and it ends up being malignant. It’s a conversation, let’s put it that way.

Complete blood count: what do the numbers mean?

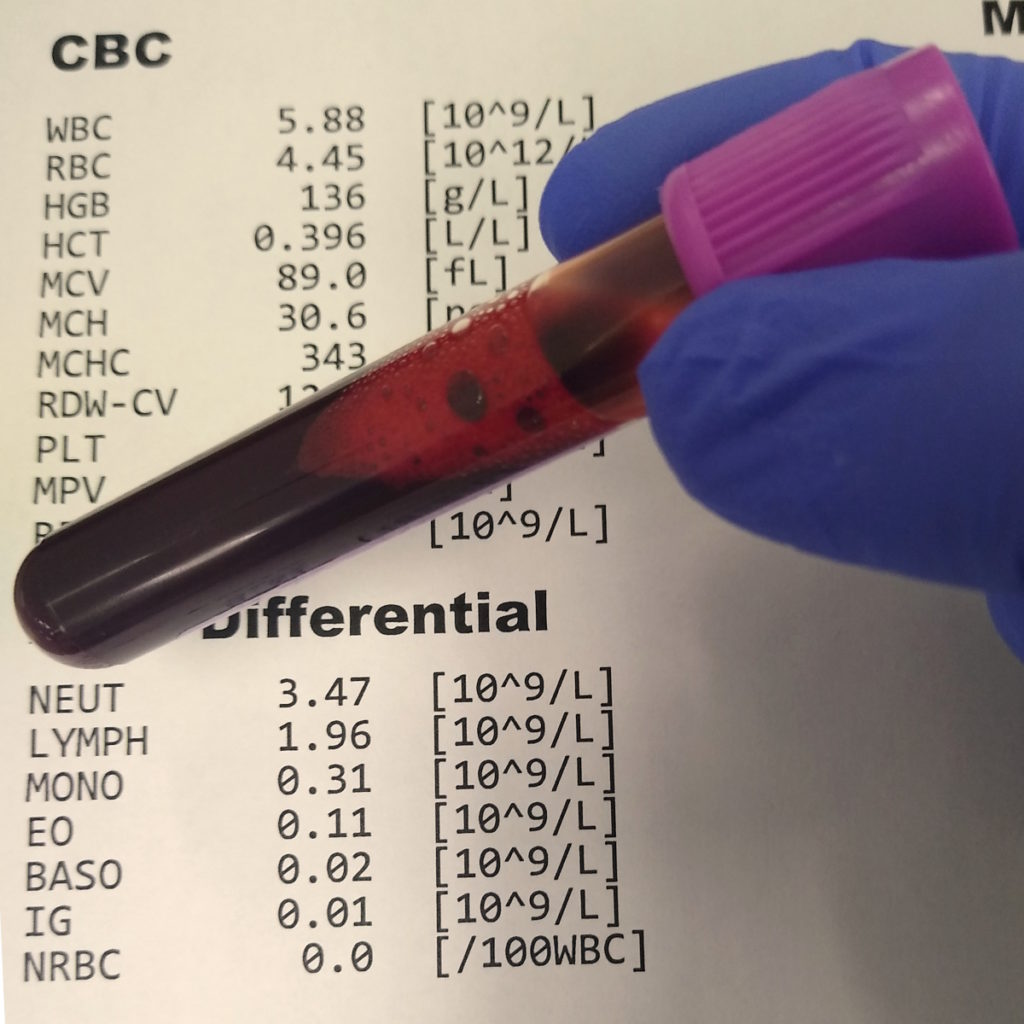

In a complete blood count, you’re getting a bunch of information. There are three main types of blood cells that we’re looking for.

There are some parameters that involve red blood cells. Typically, with red blood cells, you think of oxygen-carrying capacity so your ability to carry oxygen. The usual thing that patients may know about is anemia so that’s when you have less hemoglobin [or] less red blood cells.

Anemia means that you can probably get tired more and you have a lower ability to carry oxygen to different parts of your body. Anemia can be due to a variety of reasons, from dietary deficiencies to malignancies, and so it’s impossible to tell just by anemia what the disease is but that’s a sign. That’s what it’s showing up with.

There are a bunch of things on the CBC that talk about red blood cells. We’re looking at the numbers that tell us the size of the red cells [and] the differences in sizes of the cells. You may not need to know about all of those different granular things, but hemoglobin is probably the thing that stands out the most. The ranges are a little bit different in men or in women but, by and large, that’s your oxygen-carrying capacity.

The second number you probably see up there is the WBC or the white blood cell count. White blood cells are five different types of cells that all get lumped together and there’s a range for them.

If you have an increase in them, that again could be an increase in one type of cell, it could be an increase in all five types of cells, or it could be a decrease. In that case, it could be a decrease [in] one particular type of cell or multiple types of cells. Those are known as leukocytosis is when there [are] more cells and leukopenia is when there [are] less cells. Again, that number has a reference range.

We look at the cells and count what different types of cells they are and you’ll see that in the report. If there’s a differential count, you’ll see the words neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, basophils, [and] eosinophils. These are all the different types of white blood cells.

We can be very granular in what’s exactly happening, but these are all pointing. If there are differences or changes or if it’s falling outside the range, something is likely causing that. It could be a simple viral infection or it could be a malignancy. It’s up to a lot of interpretation and probably additional testing.

The last number that you look at is the platelet count or the PLT. These are fragments of cells that are floating around and they help you clot. They stop bleeding. If your platelet count is low, you might be getting bruises or you might be bleeding from the mouth or the nose because you’re clotting isn’t working.

Nothing is yes or no, really. It’s a lot of grey zones and so their reference ranges [are] based on your age. Some references could be different. Sometimes based on multiple different things [like] your gender.

Some people have reached out to me and said, “There’s a minor, minor increase in something,” which I don’t think is such a big deal because of experience, but for them, they think, “Oh, it’s flagged, it’s up.”

With all tests, it’s difficult for patients to predict whether a small increase or decrease is a big deal or not. But your physician, because of [their] vast experience, can help guide you. For the most part, if you’re healthy, all of those numbers are falling within the reference range and everything is okay.

Words of advice

For example, in cases of lymphoma. Lymphoma, as you know, can occur anywhere in the body, but it may occur in lymph nodes. If the lymphoma is restricted to the lymph nodes, then the presentation of the patient might be tiredness, fever, and lumps that you can feel.

If it hasn’t come out into the blood yet, the blood work may still be normal. If it spills out into the blood — lymphoma is a malignancy of lymphocytes — you could see abnormal lymphocytes, which would increase the number. When we look at them, we’d probably be able to tell that they are not normal.

Alternatively, malignancies affect the bone marrow. The bone marrow is the factory where all of the different cells are produced. If a malignancy is primary to the bone marrow, then all the blood numbers will be off. If a malignancy is metastatic to the bone marrow, let’s say lung cancer or breast cancer and it’s also metastasized to the bone marrow, then those numbers can also start looking off.

It’s a spectrum of possibilities of what that means. The blood could be completely normal and the patient has [a] disease in the bone marrow. There’s so much bone marrow that’s being produced in our bones so I think it depends on where you are in the disease. It depends on how extensive the disease is and, most importantly, what type of disease it is.

What has been the personal impact on you?

I think of the pathways to pathology in two terms. One is that, obviously, we want exceptional physicians to continue down this path because we want really good physicians to be pathologists so that everyone can get the right diagnosis. You want them to be competent and excellent. The only way to do that is to make sure that every medical student is making an informed decision about pathology.

I may be a little bit of a nut about it. My medical students think,“ Dr. Mirza always wants us to think about pathology,” and that’s fine. I don’t mind being that guy.

Coming into medical school, there are people who know that they want to be a surgeon, a cardiologist, a dermatologist, or in orthopedics. We know this.

Do you know anyone who goes into medical school thinking, I’m going to become a pathologist? It’s very rare, very rare. There are some people, but it’s very rare. And why not?

When medical students are starting medical school, they have a checklist [of] all the possibilities, but pathology isn’t even on the list. My job isn’t that you check “yes” to that box. My job is to make sure that you know that the box exists so that you can opt-in or opt-out.

The other thing is that I feel incredibly fulfilled when I am able to provide that gold standard, [that] final word on what was making the patient unwell. I hope that every single time that’s a benign diagnosis, but more often than not, it isn’t.

In those cases, as I’m driving home, even though I haven’t seen my patients, I think about this often. I’m walking to the garage or there’ll be patients walking around or patients with their families. They could be my patients and I just don’t know them. I know them by their name, their medical record number, how old they are, [and] how they presented, but I don’t know what they look like. Those could be my patients.

Every single time I’m diagnosing someone, I can almost always relate them to my circle. They’re either my age, my children’s age, my parent’s age, my sibling’s age, [or] my grandparent’s age.

If I have an eight-year-old girl who is giving the blood smear, to me, that’s my daughter. If I have a 65-year-old woman having a bone marrow biopsy, to me, that’s my mom. I really try and personalize this.

More often than not, when I’m at a junction — where I’m thinking, Okay, what should I do next in the diagnostic process? — I almost always ask myself, “If this was my mom, what would I do?” Or, “If this was my own specimen, what would I do?” Whatever the answer is is what I do. It becomes pretty clear.

For me, there is fulfillment in being able to demystify it, give them the diagnosis, and then walk away. Because now, I’ve done my job. I’ve passed the baton on to somebody else who has signed up [to] be the person who will tell the patient that they have a malignancy, who will guide them through the process, [and] who will get all the glory of the remission. They’ll get all the glory, but they also get to bear the burden of delivering the bad news and doing all of that stuff.

I go home [and] carry my patients with me, too, but I feel very fulfilled that I can hopefully do a good job in answering the questions that they need [to be] answered.

Pathology Resources

There are many resources out there about interpreting your pathology report. There is a nice resource out [of] Canada called MyPathologyReport.ca. There are other resources through the American Society of Clinical Pathology, the College of American Pathologists, [and] different support groups for patients. There are mechanisms.

Many of us pathologists are actually on social media. Find us. My DMs are open on Twitter. Find me. I may not be able to answer immediately. I don’t offer medical advice through social media, but I might be able to answer some very basic educational questions, which aren’t specific to cases. I think that that’s very important in this world where we’re so connected.

Hopefully, patients or loved ones can find the resources that they need. I hope that we can help connect people to those resources.