Self-Advocacy & Shared Decision Making in Cancer Treatment

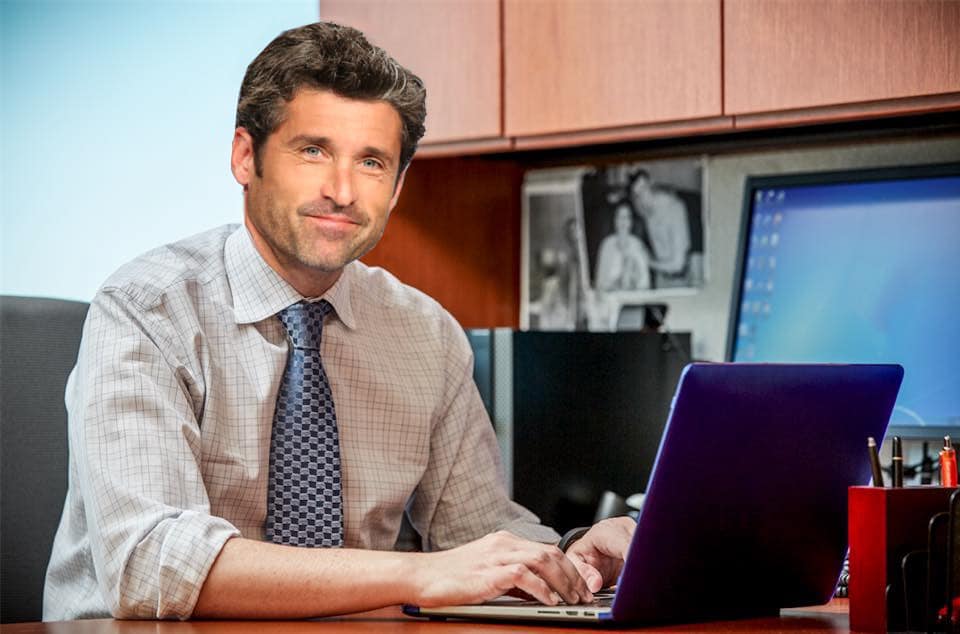

Mark Lewis, MD

Dr. Mark Lewis shares his perspective on patient care and shared decision making during cancer treatment, not just as a top-trained oncologist and director of Gastrointestinal Oncology at Intermountain Healthcare, but as a former cancer patient and caregiver, himself.

Explore below for Dr. Lewis’ insights on everything from trends in the AYA cancer patient population, the shifting patient-doctor relationship, shared decision making throughout treatment, and the importance of better interaction between patients and their doctors.

You can find the full video from our conversation here. Thank you, Dr. Lewis, for the work you do and for sharing your incredible voice!

- Introduction: Dr. Mark Lewis

- Adolescent Young Adult (AYA) Cancer Patient Care

- Personal Connection to Cancer

- The Patient-Doctor Relationship

- Shared Decision Making in Treatment

- Practice of medicine vs. business of healthcare

- Risk-benefit in choosing treatments for patients

- Patient research on clinical trials and treatments

- Importance of patient self-advocacy

- The importance of acknowledging side effects

- Your personal treatment decision-making process (Whipple surgery)

- Having the patient perspective as a physician

- Interacting with Patients

Introduction: Dr. Mark Lewis

Your motivation for sharing your voice

Thank you for having me, this is a real thrill for me, too. I’m not just an oncologist, I’m also a person. I think we can start with the breaking news that oncologists are human beings.

Frankly, that’s not a foregone conclusion, we have a pretty nasty reputation that’s come about because people naturally associate us with our treatments, and our treatments have an unfortunate legacy of a lot of indiscriminate toxicity.

One of the reasons I’m happy to do this is I want people to see that doctors, especially oncologists, come to medicine for actually pretty compelling and emotional reasons, often more than their attraction to the science.

Describe your professional background

I practice at Intermountain, which is a beautiful description of where I am. I work in Utah, I’m licensed in six states in this region, and we cover basically a pretty vast expanse.

Once you go west of the Rockies, up towards the Pacific Northwest, and across Nevada, we cover that area. It’s actually really great that I’m talking to you because, in the last year in particular, we were already doing telehealth.

The pandemic has forced us to increase our bandwidth and our ability to be facile with this kind of technology. Now I can talk to people states away.

Is it exactly the same as being together in the same room? Well, no. There is a lot of oncology actually that is appropriately tactile. That aside, it really has been a very rewarding experience.

We’ve actually had people tell us if they hadn’t had access to telehealth and oncology, they would just stay where they were and foregone any treatment whatsoever. I can actually cite examples of people whose lives have been saved by Zoom, which is remarkable. That’s where I’m at.

It’s a very different practice environment. I came here from MD Anderson Cancer Center, which is a well-known research center in Houston, and the model there was you’re going to come to us. Obviously, it’s a major metropolitan center, we have patients literally from all over the world. Unfortunately, a lot of the people who came in there had exhausted conventional treatment options, and so they were willing, they were invested.

One term that is used for folks like that is medical tourists. Sometimes people say that almost as if they’re denigrating the patient, I don’t like that. I think what it’s pointing out is there’s this select group who are sick enough to need next-level treatment, not so sick that they can’t travel, and then also with some means at least to be able to essentially move to another city to get care.

While I found that very rewarding, I would actually much rather take care of people where they live. That is what we’re increasingly trying to do with tele-oncology.

Medical training

Working backwards in my career, I did my training at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. There again, it was a center almost literally in the middle of the frozen tundra.It’s a remarkable place to visit because most people would drive down from Minneapolis–Saint Paul and you’re just going through cornfields and cornfields and it’s beautiful.

Then all of a sudden you see these glimmering towers in the distance and it’s Mayo Clinic. Boom, you’re in a world-class medical center.

There again, almost by necessity where it was located, yes, we cater to the local community. Next to my Minnesota farmer was someone who might’ve traveled from Saudi Arabia to get the latest cancer treatment. It was an amazing place to train, but again, it wasn’t really representative of the American public.

Adolescent Young Adult (AYA) Cancer Patient Care

What is the AYA cancer patient population

The reason I came to Utah is two-fold. I’m part of a dual physician couple, so my wife’s a pediatrician, and this is the youngest state in the nation. The average age here is 30. I think one in four people is between kindergarten and 12th grade.

That also means, for me, there’s this really compelling, if troubling, problem here of young adult cancer. There’s various definitions for that.

The most conventional one in the US is people affected by cancer, either a liquid tumor like leukemia or a solid tumor on the colon or breast, anytime between age 15 and 39.

This has been an amazing place to deal with that particular demographic because everyone here is, or not everyone, but many people are young. One in seven people in my practice to fit that demographic.

I think hearing them can be heartbreaking, but it can also be super satisfying, because if you can cure someone like that, that’s decades of life that you’re giving back to them.

That, in a nutshell, is my oncologic pedigree and how I got here.

Awareness of AYA cancer patient care

It’s been an amazing movement. It really has only existed for, at the most, 30 years that we’ve had this recognition that this is a group apart. Unfortunately, in that 30 years, while there’s been a lot of progress, there’s also been a lot of growth in that demographic and not in a good way.

One thing that I deal with as a GI oncologist is colon cancer, which we used to think of as a disease largely related to senescence. We used to set the screening age 50 or older; it’s happening in younger and younger people.

The example I give, which is tragic and extremely well known, is I was sitting at home last summer watching Black Panther with my son on a Friday night and my cell phone starts blowing up. It’s all my friends, many of whom are nonmedical, asking if I had known that Chadwick Boseman died of metastatic colon cancer.

I was just absolutely floored. I was watching the guy be a superhero on the screen. He’s a perfect example actually of you can be young, you can be healthy, you can be incredibly fit, you can have resources, and you can still get cancer.

Misplaced blame on (young) cancer patients

One of the things I want to touch on is the false shame and blame that is placed on cancer patients. It’s a disease that has actually long suffered from stigma for decades.

I think The New York Times actually had a ban on the phrase “breast cancer.” This was decades ago, but regardless, it goes to show you that we haven’t entirely come away from that.

Especially online, there’s a lot of unfortunate finger-pointing, especially when someone young gets cancer. The assumption is, “Oh, you must’ve done something wrong.” Far from it, it’s usually not anything the patient did, it’s some unfortunate combination of genetics and circumstance.

Personal Connection to Cancer

Your first experience with cancer

The reason I went into oncology, so not just medicine but oncology, is when I was eight years old, my father was diagnosed with cancer. The circumstances, while they’re never going to be ideal, were particularly almost Kafkaesque because what happened was we were moving to the States. When you immigrate here, you have to get a chest X-ray as a public health measure to exclude tuberculosis.

We got this call from the government saying, “There’s good news, bad news here. The good news is you don’t have TB,” talking to my dad and he’s a 42-year-old at the time. “The bad news is there’s something occupying your entire right lung. When you get to America, you should probably have that investigated.” On the phone. Click.

That’s a lot to handle when you’re moving countries. There’s some ranking of stressors and one of them is moving. I think the other is getting a major diagnosis. This was both at once. Frankly, at that time, we hadn’t learned the American healthcare system. The National Health Service in the UK is far from perfect, but one of the things it’s really good at is avoiding or minimizing financial toxicity for patients.

We got here, thankfully my dad had a job, but it was still tens of thousands of dollars out of pocket for his care. He required his entire right lung to be removed. He required radiation and chemo after that.

I know this sounds like, “Boy, after all this, why would you want to go into cancer medicine?”

It’s because his oncologist was so good and my dad didn’t pass away.

His oncologist took me under his wing. Then every summer in high school and college, I had other jobs, working in the movie theater and stuff, but I knew I had a job that I could go to as a medical assistant at this clinic, and it was the same clinic where my dad had been treated.

First, I felt a little strange going back there, but sooner or later everyone got used to me, didn’t treat me any differently than any other employee. I learned by following and shadowing this guy, how he did oncology.

Special care in patient relationships

One of the things I loved about it was I sensed how close he got to his patients. In this era, it sounds almost improper to say that, but it’s true, you get a really deep kinship, I can say that, kinship with your patients. I stopped saying “friendship” because I know there’s a power dynamic, and I know when you’re the oncologist and the other person’s the patient, it’s difficult to ever quite erase that imbalance.

Regardless, I saw what he did. This back in the era of paper charts. Before he went in the room to see a patient, and he let me follow him, he had written all the relevant medical stuff in the center, but then in the margins, you have all these tiny little details, grace notes of someone’s identity.

Then he would remember to ask them about their child playing a baseball game or, “How was this trip that you took?” I was like, wow, he’s really taking the time to learn about these people. They’re not just the host for a tumor, which is how some patients in oncology are made to feel. They’re people to him.

It took seven years for my a book my dad wrote to get published. It got published posthumously, and his friend actually showed up, completely to our surprise, on the book launch. That was seven years after my father had passed. We were just absolutely blown away. That was just the kind of connection he had.

Your own cancer story

Fast forward, I started my oncology training. Day One, I woke up with this horrible bowel pain, which naturally you could attribute to nerves. It’s overwhelming to be at Mayo and starting, embarking on your fellowship.

When I went to get checked out, one of the other things I thought it might be was appendicitis because it felt like it was in the right lower quadrant. It wasn’t. It was a high calcium level and why is that relevant? My dad had suffered from that his whole life.

No one had ever really figured that part out, and people told him, “Oh, you’re eating too much dairy.” Again, this whole shifting the blame to the patient. My dad fastidiously eliminated all that stuff, still suffered from high calcium, kidney stones, GI issues.

When I realized I also had that, the way I describe it, and I don’t think it’s hyperbolic, is you can look at the stars for a long time and then, all of a sudden, you can see a constellation, you can see a pattern. That’s what I saw.

I was lucky enough to be in the right place at the right time, with just enough training, to know that there are really only a couple conditions that give you consecutive generations of high calcium. One of them is a neuroendocrine tumor syndrome called multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1.

When I realized there was this connection, it all fit. I was starting my cancer training at Mayo, which is famously a wonderful place to be diagnosed with something esoteric, though I didn’t think I would be doing it for myself.

I went to my internist, and frankly, I don’t blame him, he thought I was a hypochondriac. Day One of oncology training, coming, and saying I have a tumor syndrome, claiming all kinds of outlandish things about my family tree.

I realize how lucky I am because if I was any other patient, if I didn’t have the ability to play the card of professional courtesy, I think it’d be written off, at least for a while.

Also, you can’t ethically order things on yourself, so I needed someone to do the diagnostic work for me. I basically twisted his arm, I said, “Hey, listen, just take a bet on me. If I’m wrong, I’m wrong, but I think I’m right,” and sure enough, I was. I disclosed that to the people who were running my training program because I thought it was important that they knew, and they could not have been more supportive.

In hindsight, it explained everything about my dad. Again, his oncologist was wonderful, and I clearly idolize the man, but he never put two and two together about what was causing my dad’s cancer. It was always dealing with what we had to confront, but no one ever got to the bottom of why it happened.

In fact, the reason I bring that up again, is my father was a Protestant minister and a theologian. He thought a lot about guilt and sin, and I wonder if in that framework, he didn’t end up blaming himself far too much.

For instance, as I mentioned, the mass started in his chest, so sometimes described to us as a lung cancer, it wasn’t really. Then he wondered, “Oh gosh, I’ve never smoked, but did I spend too much time around secondhand smoke?” Anyway, there was all this retrospection he went through and among other reasons.

I miss my dad. I wish I could tell him, “It wasn’t your fault.”

Theory: many oncologists are driven by something personal

I have a pet theory that oncologists are more likely to have dealt with cancer, themselves, than almost any other specialty.

The way I inherited my disease is called autosomal dominance. There was a 50/50 chance I was going to get it from my dad, but lightning is not always quite that strong.

My point is, many of us come to this field because, yes, the science is amazing and the pace of research is absolutely mind-boggling, but most of us come to it because we’ve known someone with cancer.

Sometimes that’s a friend; more often, it’s a relative. If it’s a relative, that means there’s some blood linkage, and presumably, some even slightly heightened risk that you might deal with it yourself.

What I want patients and caregivers to know is I was at Mayo dealing with these world-class oncologists, and so many of them, I won’t reveal their identities, took me aside after I disclosed my own problem and said, “Yes, I’ve dealt with cancer, too.” It just blew my mind.

Obviously, it’s emotional what we do, dealing with people who grapple with their own mortality, and sometimes at a very young age. I think that a lot of us do this because we’re trying to help other people when maybe we couldn’t even help our own relatives. I know I feel that way about my father.

The Patient-Doctor Relationship

Old paradigm of patient-doctor relationship

There’s a paradigm that still exists in some places. It’s paternalism, where the doctor has all the power. It used to be someone in a white coat, very stern, comes in, first appointment, “You got cancer,” we brush that aside very quickly, and then we tell you what you’re going to do.

That used to be the exchange, and it felt very unidirectional. What I would tell patients now is we live in the information age, we have more access to information than we’ve ever had before. I realize, again, the playing field is not perfectly level.

Patient access to good data

One of the things that frustrates me even as a self-advocating patient is when I try to get really deep in the weeds and research things, I sometimes come up against paywalls. A lot of research, even publicly and federally funded research, ends up being put in journals that are financially inaccessible.

It’s not uncommon and if you’re trying to get a single article, one article, it might cost you $60 just to get your hands on that one piece of paper. That really, really frustrates me.

Honestly, some of our research findings are necessarily behind closed doors. What I mean by that is they’re not ready for primetime yet. Unfortunately, oncology is littered with examples of things that have been biologically plausible or even look very promising in very early phases of drug development, but then they don’t actually work when you put them out and study them either in human bodies, or going from a test tube to a person or in large groups of people, especially in a randomized clinical trial.

Those two things aside though, I would argue that most patients have access to the same information the doctors do. The question is, how do you filter it because as you all know an engine like Google is incredible, but it’s also gameable. Google is not it’s not a completely altruistic organization. There’s a reason you get this in exchange, the transaction is you, it’s your information.

Regardless, where I want to empower patients is I’ll say, if you feel there’s something wrong with you and you feel like your doctor is not helping you deal with it, you are entitled to a second opinion.

The importance of getting a second opinion

One of the things I say is if you ask for a second opinion and your doctor says, no, that is a reason to get a second opinion.

Any doctor these days who thinks they know it all, especially in oncology, is absolutely kidding themselves.

There is so much to know. I don’t know. I know a lot of smart people, I don’t know anybody who knows everything, even in cancer. The reason I do only GI oncology now is the field is massive and unwieldy. There is no physician, there is no specialist who can possibly know everything.

The risk of getting misdiagnosed

What I would say to patients is, and I guess this is just different phases, there’s the part where you’re getting diagnosed and then there’s a part where you’re going through treatment.

I actually think the diagnosis part can take quite a bit longer. I’m not alone in that it takes on average something like seven years or even a decade for someone with a neuroendocrine tumor, which is my tumor type, to get diagnosed. The reason is it looks like so many other things.

One of the classic ways this presents is something called carcinoid syndrome, which broken down means cancer-like syndrome, and even that’s a misnomer. It can be a real cancer.

Regardless, these patients have a very classic constellation of findings. They’ll get very, very flushed, they might wheeze, and then they have horrible diarrhea, the latter of which is not easy for people to disclose.

Here’s the problem, there’s that whole parable about the blind men feeling the elephant and each feeling a different part and concluding it’s a different animal. Depending on which specialist you go to, they have anchoring bias on their discipline.

If you go to a pulmonologist with the wheezing, they might diagnose you with adult-onset asthma. If you go to a gastroenterologist with diarrhea, they might say it’s irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). For women in particular, and there’s a lot to dive into here, there often misdiagnosed with the flushing. They’re told, “Oh, it’s perimenopausal hot flashes.”

Because you start accumulating all these different and wrong labels, it can be very, very difficult to expunge those from your chart to finally arrive at the right diagnosis. What I’m getting at here is patients like me tend to have a history of either misdiagnosis or delayed diagnosis.

During this whole process, no matter how long it takes, you’re still inhabiting your body all the time. You know something’s wrong and you just can’t put your finger on it. Then presumably all of these treatments that are being assigned to you are probably also not helping as much as it’s supposed to and that’s very frustrating.

I give patients a lot of credit. I tell them, “Listen, you are you all the time. At the most, I get to see you once a week.” Most of my folks, I see every other week on treatment.

Shared Decision Making in Treatment

Practice of medicine vs. business of healthcare

Another statistic that’s amazing or scary is if we halted all oncology research today, just stopped experimenting and just applied what we already know, we’d probably save close to 100,000 lives a year.

What that tells you is the science is awesome, but there’s a huge lag in implementation, and some of it also comes down to payment. The trap I sometimes fall into is I’ll come back from one of these conferences and I’ll be giddy with enthusiasm about some new treatment, and I sometimes over promise to my patients or over disclose and I can’t actually get it to them.

One thing I say all the time is there’s the practice of medicine, which is what I do and what I’ve trained to do, and there’s the business of healthcare, which is this whole other incredibly complicated often Byzantine infrastructure.

The two are not the same at all. The training to go into one or the other is completely different. I have friends actually who have been so invested at understanding the business that they’ve gone and gotten a master’s in health administration. Those people are the exception, not the rule.

Most of us who do oncology have absolutely no idea. When we prescribe something to you, we don’t know how much it’s going to cost, we don’t know often if your insurance is going to approve it upfront, if we’re going to have to appeal, if that’s going to take time, and time is the ultimate currency.

I don’t care who you are. I don’t care if you’re Jeff Bezos, you can’t buy time. Especially with oncology, it drives me crazy because there’s that initial encounter with the oncologist. I don’t know about you, but a lot of my patients tell me they don’t really hear or retain much of that first visit beyond just the confirmation that there’s cancer.

Then the last thing you want to do once you have cancer is to wait, right? There’s this fierce urgency that comes with the diagnosis, “Oh my gosh, we know this now, let’s act on it.” Frankly, it breaks my heart sometimes because I have told someone, “Okay, we need to do X, Y, Z,” and I’ve cited this amount of evidence. But if I can’t get that to you, that is just beyond frustrating. It’s frightening.

That’s the part that makes me the most angry. I hope I don’t come across as an angry person, but I have a righteous indignation when it comes to my patients because once you’re my patient, again without sounding paternalistic, I’m very protective that I now have taken on a responsibility for you.

Medicine sometimes involves fighting with insurance companies. Now, not all insurance companies are bad, and I’m not going to name names here. I just have some I like more than others, but it is difficult for the insurance companies, give them credit, to keep their policies going at the same pace, the same tempo as the discoveries. The biggest problem in modern oncology, in my opinion, is getting the stuff we know works to the patient in a timely enough fashion.

Risk-benefit in choosing treatments for patients

One thing I’ve been very interested in is sometimes you get to a crossroads in someone’s treatment and there is more than one option that you can reasonably pursue. What I’ll often do is spill out to the patient, “We could do A, B, or C,” and I try to build in a risk-benefit calculus, if you will, to each option. It’s very interesting because it’s almost half and half.

I’ve got some young patients, but the average age of my patient is 68, and it’s probably from the generation that’s more used to the doctor telling them what to do. Some of my patients tell me, “Listen, you pick, I don’t want the burden of picking.”

Others are deeply interested in researching which path they’re going to be on, and I give them the time and hopefully the information so they can do that. It’s really fascinating. We want to offer autonomy, but we don’t want the weight of that to be too hefty.

Patient research on clinical trials and treatments

I see a lot of patients coming in and they’ve done a lot of homework online, but one of my favorite things that happens these days to really flip the script around is a patient will tell me about a trial that I haven’t even heard of.

Again, no oncologist knows everything, and because there’s new studies opening up all the time, even those of us who really try to keep our finger on the pulse, we don’t know it all.

Occasionally a patient will come in and they’ve gone to clinicaltrials.gov, the central clearinghouse for all this, and they’ve put in an appropriate search string. They’ll say, “Hey, Dr. Lewis, would this be right for me?” Then we read over it together, and it’s either yes or no, but it’s a really cool process.

Get to the point where you can have a true dialogue, not be worried about offending your doctor’s sensibilities or whatever.

Importance of patient self-advocacy

Here I will invoke older generations. My Scottish grandmother, bless her heart, was in her 90s had a heart attack on a Sunday, a crushing chest pain. She didn’t call anybody until Monday morning and survived. When we asked why, she said, “Oh, you don’t bother the doctor.” I often say to my patients, “You very much bother the doctor, that’s what we’re here for.”

In my group, we’re fortunate we have a system where we trade-off, but we cover our clinic 24/7. If you’re having a heart attack, we want to know about it. The other thing is there is a lot we can tell about you from labs and scans, but as I mentioned earlier, you’re the ultimate surveillance system for your own body. Without making it too onerous on the patient, there are certain side effects I just can’t see.

The classic one, and this is appropriate across a variety of different tumor types, is neuropathy. A lot of the drugs that we give in oncology, unfortunately, have a really nasty downside, which is potentially permanent nerve damage. The problem with it is usually once it happens, it is not reversible.

It is a case where an ounce of prevention is a pound of cure, and the only way we can mitigate it often is to be extremely careful with our dosing upfront. All my patients know, I’m on them constantly, “How are your nerves this cycle? How are they now?” The reason I do that is I know that some of these drugs, I just can’t take back.

Mayo is a world-class center for multiple myeloma, a plasma cell disorder, and classically the drugs that they use in multiple myeloma can cause neuropathy. I’ll never forget this. You tend to remember your mistakes more than your successes.

I was in training, I was presenting to, if I’m honest, a pretty fearsome myeloma professor, he was the chair of the department, and he’s a very opposing man. I suppose I was trying to placate him. I described to him that a patient quote, my exact words, “Only had grade two neuropathy,” and he stopped me. He said, “You will never say that again. You’ll never say ‘only’ about someone’s side effect.”

He’s absolutely right because on this scale, grade two neuropathy means you have constant numbness and tingling. It’s not anything that you would want.

The importance of acknowledging side effects

The other thing I’ll point out as a patient, phrases that drive me the craziest in oncology, are the rhetoric that tries to minimize side effects. The phrase that I hate the most if I’m very honest is “manageable toxicity.”

Often what you’ll find in a scientific conference is a drug might actually work very well, it may be highly effective, but as we hinted at the very beginning, might also be really toxic.

What’ll happen is you’ll see these researchers, understandably they’re excited to share their findings, but sometimes they tend to sugar coat whatever this new treatment is. They’ll throw that phrase in. The reason I find it so objectionable, it’s almost sophistry, is when they say that, my retort is always like, “Well, if it’s so manageable, would you want to take this drug yourself?”

It’s really interesting. If you poll our oncologists, I think this has actually been done sort of formally, but you can do it informally and say, “Hey, would you be willing to take x, y, z?” Many people would say no.

At Mayo, in myeloma, I came across this chemo recipe we were giving. I’ll be honest, I thought it was a misprint. It was seven drugs put together. I was like, “There’s no way. There’s absolutely no way this is an accurate acronym.” Sure enough, it is; it’s a seven-drug regimen.

There are many of us who, if you really put our feet to the fire, would not accept the very things that we have been trained to prescribe. That kind of, I guess I’ll say it, hypocrisy has also not served as well in terms of our public image.

The goal, and I tell my patients this all the time, is to marry effectiveness to tolerability. Especially if you’re a young person and I think you can live for decades, I want you to live for decades with a good quality of life.

The tough part is sometimes to get to cure, you have to basically put the patient through just the most exquisite rigorous procedures, like a bone marrow transplant or something. If you can get them out the other side and they’re relatively intact, that’s the goal.

Your personal treatment decision-making process (Whipple surgery)

This was what my pancreas used to look like, and now I’ve lost basically the part that I’m covering with my fingers. I’ve got the back half but I lost all this. Unfortunately, this is the more important half.

Because I diagnosed myself right as I was starting my oncology training, I saw my entire process of being a fellow. Three years I was learning the field, then ever since I’ve been an attending, I’ve always seen it through the lens of being a patient, too.

I was very lucky. I still have tumors in my pancreas, but the most bothersome tumors I had were slow-growing and in a tricky place, which is the head of the pancreas. If I flip this model around, you can see there are tons of blood vessels. The common bile ducts, it’s very high-value real estate. It’s the Manhattan of the abdomen. I didn’t want to intervene on it until I absolutely had to. Here again, I empathize with patients because I was at Mayo and I got three different surgical opinions.

Depending on which expert you go to, you’re going to get a different answer. I went to one guy, he said, “Oh, this is easy. Let’s take the whole pancreas out.” Well, okay. Surgically, actually, that would have fixed the problem, but talk about quality of life.

At least at the time there was an estimate that that would have taken over a decade off my lifespan because your pancreas does some important things. Rather famously, it makes insulin. Now we’ve come a long way now with insulin pumps, and so there are people who live without a pancreas, on an artificial pancreas, and they’re able to have insulin infused almost continuously should they need it.

What many of them can’t do though is bring their blood sugar back up. High blood sugar is bad in the long run, low blood sugar is acutely life-threatening. They live in this very, we actually used the term, brutal existence, brutal diabetes. I didn’t want that.

I knew option A, I didn’t want that. I’m genetically mutant so my whole pancreas is weird, but regardless, the biggest ones were up here in the head. For Option B, they said, “Well, we can do the Whipple procedure, so we can just cut this part off.” I asked if that was going to affect my training. They’re like, “Oh, yes, you’ll be gone for months.” I was like, “Well, I don’t really want to do that.”

Then the final option, which is what I took at the time, was observation. This part appealed the most to the logical part of my brain. They said, “Two points make a line, so rather than jumping right in and doing surgery, why don’t we just see how your tumors grow?”

That came with its own risk that these tumors were going to explode, they were going to become inoperable, they were going to spread. Based on what I understood, that seemed unlikely, and so we watched. I was able to watch for eight years before a tumor in the head of my pancreas did exactly that and exploded in growth. Then I knew it was time. I knew it was time for surgery.

By that point, I was already working here. I had a very supportive employer. They said, “Of course, you can do this and you can take medical leave.” I took the right amount of time and then I came back.

Having the patient perspective as a physician

What’s been really funny for me, I say funny and really has been rewarding, is because I was so open about going through that, it’s actually enriched my practice. I actually have people who seek me out because they have pancreas problems, which I can totally relate to. They’ll say, “We came to you because you get it.” I kind of do, but in some ways, I don’t because I have the less typical form of pancreas cancer.

The more typical form is more aggressive than what I have had to deal with, almost always requires chemo and can require radiation. I have not yet needed those things. Again, I know not quite what I say when I talk about chemotherapy and I tell the patients that when they’re like, “Oh, you get it, you empathize.” I’m like, “Well, I can to a limit,” I can empathize with dealing with the diagnosis, dealing with something that is genetic.

Interacting with Patients

Importance of real-time doctor-patient communication

Frankly, one of the huge advances in the last couple years has been real-time communication with patients. There’s a really famous study, you might actually know of it, but it was presented at one of our meetings in 2017. As is often the case at oncology conferences, it was a survival curve.

What that means is you’ve got two lines and one line shows you how people are doing with intervention A and the other with intervention B. What I’m telling you is if you put up just the slide, just this, the curves, and you saw the separation between these two groups, you’d be like, “Oh my gosh, whatever drug they’re giving to group A, this is a billion-dollar product. This is going to be like blowing the doors off and changing the standard of care.” It wasn’t a drug.

It was a computer program based on people’s cell phones where they could just note in real-time when they were having symptoms and then fed back into a system involving nurses and doctors where they could respond in real-time.

That was the survival difference. My point is just listening to people as close to their present experience as possible, that is so powerful.

The power of social media

There’s a lot of fire for further conversation there, but I’ll just say in my career, which has not been that long, I’ve seen social media go from something that was considered frivolous and unprofessional for a doctor, and certainly oncologists, to something that’s almost become, not mandatory, it’s strongly encouraged. There are a couple of reasons for that.

I did a Google search where I let the search engine auto-complete the phrase “oncologists are,” and what came up, at least for me, was oncologists are murderers, oncologists are criminals, oncologists are poisoners, all this stuff. I was like, “Holy smokes, these are the top answers on Google?” I was like, “I got to do something about this.”

You feel like a tiny drop in a big ocean, but I thought one thing I could do is be open.

Now with that, I’ll say a couple of things. Vulnerability is the right word because you do make yourself potentially a target. It’s very seldom, thankfully, but I’ve dealt with trolls, dealt with death threats at one point, dealt with pedophilia towards my children, and all these really, really horrible things. Thankfully, that is the tiny, tiny fraction of my social media experience. Some of my peers look at that and they want nothing to do with it. I don’t blame them.

However, it’s also become a tool, if I’m being very honest, for oncologists’ professional development because as I mentioned earlier, there is so much to know. What we can do as doctors is use it to refine our own information stream.

If I just sat and tried to read every cancer research article that came out, I wouldn’t be able to do it. I certainly wouldn’t be able to practice at the same time. There’s some point where you just get oversaturated and frankly, it’s not all equally meritorious either.

One of the things that’s good about Twitter, and this may not be not so visible, is using it as a curation tool for us. Also is important because it lets you see what matters to patients. If you listen to advocates, you learn a lot. We have almost countless other metrics that we like to use to say, “Oh, treatment X is better than treatment Y.” Very few of them matter to patients. At the end of the day, they’re often just very poor surrogates, if they’re surrogates at all, for living longer and living better.

Then there’s the tone on Twitter. I tweeted about that this morning. It is really, really hard because there’s no font. You can’t really broadcast clearly when you’re being sarcastic versus being genuine, so I’ve learned to try not to be the former. The tone is really tricky.

One of the things I’m told is sometimes I tweet about heavy stuff, “People are dying.” Then people are like, “Oh, you’re so serious.” Then I try to be comical and get, “Oh, you’re being far too glib for an oncologist.”

You can’t please everyone all the time. I love the conversations that happen there, I love the fact that you and I met.

The importance of patient stories

Your platform does an awesome, awesome job of storytelling. Again, this might actually be the central tension I think between patients and oncologists. We love numbers, we love data, and the way our studies are set up, we’re supposed to look for statistical power, right? We need big enough numbers to be sure that our conclusions are generalizable.

In the process though, we discard individual experiences, so N equals one (n = 1). There are very, very few studies that you’re going to predicate just based on the experience of one person. Unfortunately, what that’s led to is we get all myopic about the numbers and the graphs. We forget about the people.

One of the things that I’ve also tweeted and written about is that survival curve I mentioned earlier. Every time it notches down, we’ve lost somebody. We need these graphics to be able to visualize the data, but sometimes I stare at them, especially when they plunge, you’re like, “That was people dying.”

That’s where stories are so important. Joseph Stalin, a weird person to end with, I know, said, “A single death is a tragedy, a million deaths is a statistic.” That’s so powerful, and I actually talk about that a lot because he’s right. We are narrative creatures, a story resonates with us. Most of our entertainment is about narrative.

When you hear someone’s experience the way that your platform allows, it’s so resonant. Then when we take that and put it in numerical form, it’s like we’ve cut away the human husk and we’re left with this kernel of information, but we can’t discard that person’s humanity in the process. That’s the disconnect, especially when I go to these meetings.

That’s where I feel really lucky because I’m occasionally given a podium or a microphone, and I get to speak up as a patient.

Again, I’ve been very demonstrative on Twitter. I love it when someone said I was performative, I was like, “Well, I didn’t go through pancreas surgery to gain clout.” I think anybody can call you performative, and you can say your virtue signaling. These are often very telling accusations about the person who’s slinging mud at you, regardless.

I feel very privileged. I feel privileged to talk to you. I also feel privileged to talk to my peers. I am the furthest thing from the world’s greatest researcher, I’m actually not very good at the really, really rigorous clinical trials that are going to move the field forward.

What I can do, what I try to do, is speak up if I see us focusing so much on effectiveness or some metric by which we assess it and forget about the patients. Again, that goes back to toxicity and what you were saying earlier about balancing out longevity and quality of life. That’s the whole point, is that we want both. We really want both.

More Oncologist Conversations

Dr. Christopher Weight, M.D.

Role: Center Director Urologic Oncology

Focus: Urological oncology, including kidney, prostate, bladder cancers

Provider: Cleveland Clinic

...

Doug Blayney, MD

Oncologist: Specializing in breast cancer | HER2, Estrogen+, Triple Negative, Lumpectomy vs. Mastectomy

Experience: 30+ years

Institution: Stanford Medical

...

Dr. Kenneth Biehl, M.D.

Role: Radiation oncologist

Focus: Specializing in radiation therapy treatment for all cancers | Brachytherapy, External Beam Radiation Treatment, IMRT

Provider: Salinas Valley Memorial Health

...

James Berenson, MD

Oncologist: Specializing in myeloma and other blood and bone disorders

Experience: 35+ years

Institution: Berenson Cancer Center

...