Breast Cancer Oncologist: HER2, Estrogen+, Triple Negative | Dr. Doug Blayney, Stanford

- Name: Dr. Doug Blayney

- Role: Oncologist

- Specialty: Breast cancer

- Experience: 30+ years

- Stanford (current)

- University of Michigan

- Wilshire Oncology (private practice)

- Message to patients: “Almost everyone I see is very scared of what this diagnosis means, what it’s going to mean for their life in the next few months or years hopefully, and what it’s going to mean for the relationships with their family. There’s a big team around us here to help you get through that.”

- Breast Cancer

- In layman's terms, what is breast cancer?

- What are the best ways to catch breast cancer?

- What are the most common symptoms of breast cancer?

- What kind of testing is required for diagnosis?

- What is a core needle biopsy?

- What are the most common types of breast cancer?

- What is the treatment for each type of breast cancer?

- What are the general side effects for these treatments?

- How do you stage breast cancer?

- What is the prognosis for each main breast cancer type?

- Can people work through breast cancer treatment?

- What are the biggest misconceptions about breast cancer?

- Relationships with Patients

- Describe the oncologist's role in the breast cancer journey

- What is your typical work day as a breast cancer oncologist?

- Who are the different players on your medical staff?

- What do you typically say to new patients?

- What can cancer patients expect from you?

- What do most cancer patients ask about?

- What questions should cancer patients and caregivers be asking?

- Can a patient request a specific doctor?

- Advice to patients about how to build a relationship with the oncologist?

- Advice to patients about balancing being a self-advocate and listening to experts?

- How can oncologists improve the patient experience?

- Describe your experience at a smaller vs. larger hospital

- Any message to new patients?

- What is the best part of being a breast cancer oncologist?

- What drew you into oncology?

The part of the day I enjoy is opening the door and closing the door, knowing that we’ve solved together a patient, family and my team, problems that can be daunting at the outset.

Sometimes they’re simple solutions. Sometimes those solutions are complex and take a long time but knowing that we’re making progress toward a solution is what brings me satisfaction.

Dr. Doug Blayney

Breast Cancer

In layman’s terms, what is breast cancer?

Remember cancer in general has several characteristics. It’s an uncontrolled growth of normal cells that have acquired or figured out how to invade normal tissue, spread to other parts of the body, grow there. So a seed that starts growing, and brings blood vessels and nutrients to itself.

All four of those characteristic: uncontrolled growth, invasion, spread, and bringing nutritional sources to it is what cancer is.

Breast cancer is cancer that starts in the breast. Both men and women get breast cancer. It’s much more common in women because women have more breast tissue than men. But there’s some peculiar or relatively unusual aspects of breast cancer. It’s one of the few cancers we can detect early by physical exam.

What are the best ways to catch breast cancer?

Women now have permission to examine themselves. 40 or 50 years ago, examining one’s own breast or having a ulcerating or bloody big lesion was something to be ashamed of. We saw a lot of breast cancers that were big and uncontrolled when they were first diagnosed.

Now, most cancers that we find are either picked up or discovered on mammogram, or discovered by women or their sexual partners, themselves, so we have an opportunity to discover cancer earlier in the breast and at a much more treatable stage.

We can, if it’s caught early, make it go away and stay away forever.

What are the most common symptoms of breast cancer?

The most common way breast cancer is discovered Is either feeling a lump or having an abnormal mammogram. It can happen but it’s pretty unusual these days for there to be bleeding from the nipple or nipple discharge that can happen. When it does, it doesn’t mean cancer. But it’s certainly something that should be investigated.

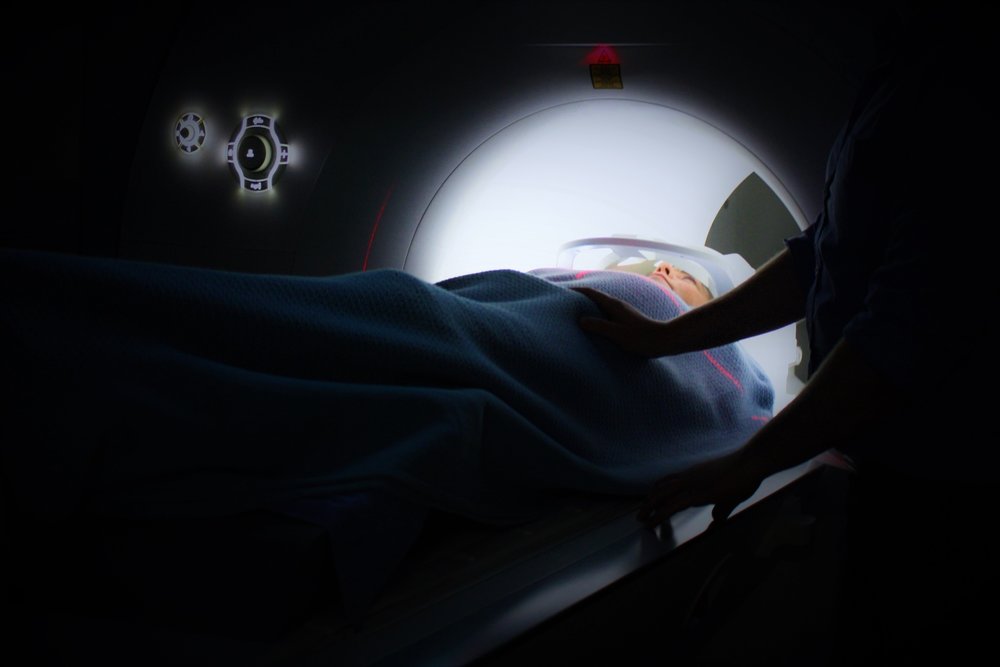

What kind of testing is required for diagnosis?

When breast cancer is first discovered, we often do staging tests. If there’s a high suspicion that a cancer has spread outside the breast, we might do a CT scan or computed tomography scan, a bone scan or PET scan, a positron emission tomography , or PET scan.

Many times it’s not necessary to do those radiographic tests or those X-ray tests if the cancer in the breast is small and if it has not spread to the lymph nodes.

We often don’t, and even more so if a patient has no symptoms, we often don’t do those X-ray or staging tests.

What is a core needle biopsy?

Within the past ten years or so, the approach to new breast cancer has changed. Almost always now the first procedure will be some kind of core biopsy or needle biopsy of a breast mass that either they feel or has been seen on an image.

The core biopsy is done under local anesthesia and that allows the surgeon or other members of the treatment team to have a more rational approach to the surgery.

Sometimes we do chemotherapy or hormone therapy before doing the surgery that allows the surgeon to have a smaller operation many times.

A core needle biopsy is usually the first thing that’s done so that the treatment can be planned to have a minimal side effects, and the most chance of cure and best cosmetic outcome.

What are the most common types of breast cancer?

I think the two main kinds of breast cancer that I would think of is:

- Localized breast cancer we can treat first surgery and often with radiation after that, then perhaps with some systemic therapy that we’ll talk about in a minute.

- Then there’s cancer that may have started in the breast and spread elsewhere. That’s called disseminated, metastatic or some people call that stage 4 cancer.

So the stage 4 cancers we have to treat systemically because they cause problems in the whole body. The earlier localized breast cancers we often treat and can cure many of those localized breast cancers.

In breast cancer, we’ve come to for practical purposes, descriptions about ways to treat it. So I think of estrogen-receptor positive breast cancer as more common overall and much more common in older women, post-menopausal women. The reason we call it estrogen-receptor positive is because we can treat it based upon hormonal treatments or anti-estrogen treatments.

There’s also about 25-percent of cancers that are called HER2, over-amplified HER2. It goes by several names.

It’s a signaling pathway that when turned on tells a cell to grow. The treatment for that is to turn off that signaling pathway. So that’s the second type of breast cancer that HER2 positive.

Then there’s the other cancer, triple negative. Meaning it doesn’t have estrogen or progesterone receptors on it. Nor does it have HER2 on the cancer cell and that’s a little different kind of cancer that we treat in several different ways.

Traditionally, we use chemotherapy, but we’re discovering there are other ways of treating triple negative cancer and we’ll divide that up in different segments, as well.

What is the treatment for each type of breast cancer?

In general, breast cancer when it’s confined to the breast it’s treated with some sort of surgery. Lumpectomy, meaning taking out the lump, or a small operation through typically a small incision, commonly the lymph nodes under the arm or axilla are examined in some way.

Sometimes the surgeon would remove one or two of the lymph nodes, so-called sentinel lymph nodes. Those are examined under the microscope and doctors make decisions based on if they have cancer in them or not.

If the tumor is a large mass and the woman may have small breasts, a mastectomy or removal of the whole breast is necessary to get the tumor out completely.

There are times reconstruction is done after the mastectomy. Very often that’s accompanied with a tissue expander so really a balloon is placed under the skin and inflated slowly to stretch the skin out so a more permanent reconstruction can be done 2, 3, or 5 months later.

Surgery is the mainstay of treatment for breast cancer.

Very often if a small operation’s been done, we do radiation treatment so radiating part of the breast prevents any recurrence there to prevent the cancer from coming back in the breast.

If there’s a high chance the cancer has spread outside the breast and planted little seeds in other parts of the body that may start to grow at some point, we often give systemic treatment or systemic therapy to kill those little seeds.

We know if those seeds start growing or if the cancer comes back, we can’t cure it at that point whether it’s two, five, 20 years down the road, we can’t cure it if it comes back.

We often use systemic treatment after surgery as an adjuvant to surgery. That’s where the term adjuvant chemotherapy or adjuvant hormone therapy comes from.

We use a systemic treatment to kill those little seeds.

Sometimes we use chemotherapy which damages fast-growing cells. Sometimes we use chemotherapy and anti-HER2 therapy. Sometimes we use anti-hormone therapy. It depends on the characteristic of the cancer cells.

What are the general side effects for these treatments?

What I tell women is that chemotherapy damages fast-growing cells. One can predict what the side effects might be. The fast-growing cells in the body may be the cancer cells and that’s why we use chemotherapy to damage those fast-growing cells.

The other fast growing cells are in the hair so many chemotherapies cause temporary hair loss because we damage those cells.

The other fast growing cells are in our GI tract, mouth, so sometimes mucositis or sores in the mouth, or nausea and vomiting can occur. Other fast growing cells is in our bone marrow so white blood cells or platelets can temporarily be damaged with chemotherapy.

Other less common side effects are the nerves can get damaged temporarily. I tell women almost all always that your energy will be down. You won’t be able to do as much as you did before.

But it’s important to push yourself through and not fall off your exercise program during this time because one of the ways we prevent side effects is with exercise. It makes people feel better. It helps with the brain, thinking, and it also helps to not gain weight so exercise is good for all these side effects of chemotherapy.

Anti-hormone treatment in general, anything that can happen with hormone shifts of pregnancy can happen with the hormone shifts of anti-hormone, anti-estrogen therapy. Range in hot flashes are most common. Sometimes there are joint aches or arthralgia that happen. Depression, blood clots, and uterine cancer are rare but can happen.

How do you stage breast cancer?

I talked about localized and systemic breast cancer. Many years ago, a staging system was devised in all cancers. Breast cancer the early stages are typically stage 1 or 2, some stage 3 cancers are early stage and typically confined to the breast so surgery is appropriate to remove those and can be curative in those stages.

Stage 4 in breast cancer and other cancers as well means that the cancer has spread or metastasized outside the organ where it started.

What is the prognosis for each main breast cancer type?

In general the estrogen-receptor-positive cancers are very slow-growing. We can cure many of them especially when they’re discovered early. They can relapse five, 10, 15 years after the first treatment. That’s what makes them a little disconcerting or spooky, frankly, to doctors and patients. We’ve learned that it’s wasted time and energy to do regular blood tests or CAT scans. We typically only do mammograms to pick up any new cancers that might occur in the breast.

For the HER2-positive cancers, the discovery in the last 20 years, that’s the HER2, anti-HER2 treatments, trastuzumab, pertuzumab, Lapatinib, other anti-HER2 treatments have really made them a much better prognosis cancers since those treatments became available.

If they’re going to recur, they recur sooner after your diagnosis. Typically in five years is at least a window or reasonable milestone to get through. Doing surveillance, CAT scans, or PET scans, or blood tests is not useful.

Finally, for the triple negative cancers, if they’re going to recur they’re going to recur much sooner. We’re making good strides in keeping that from happening but they recur much sooner than the HER2 or the estrogen-receptor-positive cancers.

Can people work through breast cancer treatment?

In regards to work the answer is like a lot of things, it depends. Younger women I think can work through chemotherapy. Younger people have more energy than older people. They have more reserves of energy. Often older women I’d advise they take off work or certainly let their employers know they’re going to be having to focus on other things besides work, and hopefully their employer can make some accommodations for that.

In breast cancer, we’ve tailored therapies to estrogen-receptor-positive, that’s been known for some time, so we treat estrogen-receptor-positive cancers differently than we treat non-estrogen-receptor or triple-negative cancers.

»MORE: Working during cancer treatment

We’re learning more about triple-negative cancers. Sometimes we use immunotherapy, sometimes we use therapies based on specific genetic abnormalities that occur in the cancer cell and as time goes on more genetic abnormalities accumulate and we’re learning about how to do that in breast cancer.

I think where we’re going is we’ll treat cancer not so much as where they started but more targeted on what is the triggering mutation in the cancer.

So for instance, I mentioned earlier HER2-positive breast cancers. There are some HER2-positive gastric (stomach) cancers that are treated with the same agents.

There are some, a few head and neck cancers that also are HER2-positive and treated with HER2 agents so that’s an example of where we’re going and I think that’s what we need to expand more in the next 10 to 15 years.

What are the biggest misconceptions about breast cancer?

In the past 10 years we’ve seen a lot of women who opt for a mastectomy and sometimes that’s bilateral meaning both sides mastectomy. That’s a woman’s choice and I support that, my team supports their choice. But people need to understand that removing the whole breast doesn’t have anything to do or doesn’t influence or improve the long-term prognosis.

So many women will opt for a small lumpectomy. I’ve seen a lot of women who’ve had lumpectomies three to four years ago, it’s often very difficult to see the scar. So a lumpectomy for a small tumor has excellent cosmetic results and is really difficult to tell if there’s been an operation.

Again, mastectomy and reconstruction is an involved procedure. We have very good results from that as well but again, unless the tumor is large, a mastectomy doesn’t have any survival advantage over lumpectomy, lumpectomy being the smaller operation.

Relationships with Patients

Describe the oncologist’s role in the breast cancer journey

There are many specialities of physicians you’ll meet along the way. One of the joys I get from practicing medicine and practicing cancer medicine is the ability to work with highly specialized surgeons, pathologists, diagnostic imagers or radiologists, and medical oncologists such as myself in the physician role.

Typically, physicians diagnose and treat cancer or other diseases but we have a big team that works with us. While physicians are often the head of the team, set the general direction, and give you as a patient and family advice, we have very specialized members of our team with very specialized experience and training and expertise who’ve been down this road many times before.

What is your typical work day as a breast cancer oncologist?

I have a variety of roles at Stanford. Part of it is patient care. I do that several days a week. I also do research and do writing several weeks, so some administrative work.

When I deal with patient care I think the most important part I do with parts of my team is we go over the schedule of each clinic.

We try and highlight what we think is going to be important in that visit for the patient and if my nurse or the medical assistant or somebody else has word of some other thing that I haven’t picked up on, we gather the whole team’s input so that we can be most efficient and listen when a patient and their family comes in. So preparation is a big part of what I do.

Then when we visit with patients it’s always a surprise. It’s sometimes it’s a fun surprise, sometimes it’s a challenging surprise. We’re here for the patient. I think we try to respect everybody’s time and be efficient when we do that.

Each patient interaction is different. I have a friend who says the reason I get through the day is: behind every door is a story. I like to hear what patients have to say and to hear their story.

There are certain things that I do and that my nurses do to set up that story so we can get right to the point of what’s important. But hearing the story is important.

I always tell my trainees and people whom I work with, if you let the patients talk they’ll typically tell you the answer.

From a patient standpoint I always find it helpful if there’s a list of important things to talk to so that helps me direct my efforts and helps my team direct our efforts to what’s important for the patient.

Sometimes, small trivial things spin off into great long important conversations that either I have to take time to do later or we have a specialized member of our team to address.

Who are the different players on your medical staff?

We have social workers and financial counselors that work with us. Many patients are reluctant to share with their physician or don’t want to waste their time, coming to treatment might be a big chunk of their day.

They might have to take time off work or more importantly, a daughter, son, or husband may have to take time off work. I don’t have the expertise to deal with that but there are solutions that often our social workers might have, our financial counselors might have, as well.

Similarly, we have genetic counselors. One of the interesting things that I’ve seen in the last 15 years of doing breast cancer work is we’re understanding more and more about the familial aspects of breast cancer.

We have genetic counselors who can advise not only us and the patients on what the right thing is to do but also can advise a patient and discuss with their mom and their sister or some other loved one what the implications of a genetic test might be before we do the test, so everyone can be set up for the answer.

As we get into the diagnosis and treatment of cancer, often we use chemotherapy. Chemotherapy are drugs that are usually given in the vein. Typically that treatment is administered by nurses with a lot of experience starting IVs or starting intravenous line.

Or if we need a port or venous access device, they’re pretty good at knowing when that needs to happen. Our chemotherapy nurses are tuned to pick up side effects and toxicity and be there for the patient. So the expertise of our chemotherapy nurses is important as well.

Similarly we have pharmacists who are trained and experienced on chemotherapy and its administration. Trained for drug interactions and picking up potential side effects.

Those are the team members that I work with when we administer chemotherapy. In addition, there are many of the chemotherapies we have now that are oral meaning pills patients, that you might take home, and take daily or on some more complex schedule.

There are pharmacists we work with who help manage that and also work over the telephone to work with people where they are so we can hopefully manage the side effects and pick up the side effects early. So hopefully we can manage side effects and pick things up early, make any course corrections.

Many of the therapies, not only chemotherapy, but some of the anti-hormone therapies that we use, and radiation therapy, all have side effects or unintended effects or unintended consequences of their use.

I think it’s helpful for patients if they keep a list of things that are bothering them, they can bring it up with me next time they see me or with a nurse practitioner with whom I work, or the chemotherapy nurses if a patients is seeing the chemotherapy nurse very frequently.

Let’s talk about nurse practitioners and physicians assistants for a minute. Those professionals are members of the team as well. Very commonly, I and other docs will work with a nurse practitioner or physicians assistant.

As I mentioned, I have multiple missions. I had work in education and do research so I can’t be in the clinic all the time. Often my nurse practitioner and I will trade off seeing patients or see them together. We each have different skills and different experiences that we can bring to bear in management of the cancer and its side effects.

What do you typically say to new patients?

I think it’s important, just as in any professional interaction, that we introduce ourselves. If I have a nurse practitioner or a student, introduce them. Whoever’s with the patient whether it’s a spouse or son or somebody else that’s completely unrelated, it’s important to let everybody know that we can talk openly. Or if we can’t, for a patient to say I’d rather discuss that just between you and me. Introducing is important.

I typically ask what I can do or what the patient expects of me, what they’re looking for, whether it’s we’re going to enter into a course of treatment, whether they want some advice relative to what other docs or people have told them, a so-called second opinion I think.

We’re all upfront. It’s important to be upfront and to let people know what’s expected and we can be efficient in a use everybody’s time that way.

When I meet a new patient we go over their history and what they’ve experienced thus far. I match that up with any records that I’ve received and often we go over well, usually patients have this experience – did that happen to you? Oh yes, I forgot to tell you about that. Or, no it didn’t happen. Well it doesn’t mean it should or shouldn’t, it is. We have to go forward from where we are.

I think it’s important to say that there’s no silly or stupid question. The only stupid question is the one that doesn’t get asked.

Again if you have a list of important things, just make sure all those are answered. Often, patients will come in with a list and at the conclusion of the visit. They’ll say you answered this, this, this, and oh yeah, you didn’t talk about this. Often I and most oncologists who’ve been through this enough times we anticipate what’s important to the patients and what they’re going to ask, and what they’ve been coached to ask. Often their husband or family member have suggested that they ask, as well.

What can cancer patients expect from you?

Most patients I meet for the first time are really scared. They’re scared because somebody’s told them they have cancer. Cancer is a very spooky word, rightfully so. Everybody including their families is scared, almost without exception.

My role, just as a surgeon, just as my radiation oncology and other people who deal with patients face to face, is to help get through this crisis and come out on the other side in a better place.

My role and that of my colleagues, radiation and surgeons, is to help people deal with the spooky, scary time in their life and to get through on the other side so they can either go on and resume a normal life. Or if it’s not going to turn out that way, to come to terms with what is going to happen. If the cancer is going to carry them away and be fatal, we need to help everybody understand that and help understand what that process is going to be like.

What do most cancer patients ask about?

Most everybody asks about prognosis in one way or another. The underlying question is is this cancer going to kill me? Is it fatal? So most people ask that in one way or another.

It’s often embarrassing because it’s not a question that people have ever asked before. I often try to head that off by saying yes or no, this could be fatal, or very likely to be and describe what I see potentially happening.

I am not always right but often within various parameters or limits, we can make some good and educated guesses or estimates. Most people want to come away from the first or second visit understanding that.

Second thing with chemotherapy, with surgery, with radiation – they all have side effects. Almost everybody asks what are the side effects, what’s the downside of this treatment you’re proposing, what are the risks?

While we can’t be exhaustive, I try to hit the common ones and how we mitigate or deal with those side effects. So the prognosis and the side effects of the treatment are something most people ask about.

What questions should cancer patients and caregivers be asking?

If coming away from the first couple of visits you’re not clear about the prognosis and you’re not clear about the potential side effects, make sure you understand the potential benefits of any treatments that’s proposed or offered.

One of the things we don’t do great at is understanding what are some of the long-term effects. Am I going to be able to go back to work or back to my life that I had before? Those are some of the things that get asked.

Another thing that sometimes people don’t come to terms with is how is this going to affect my relationship both personal and sexual?

With my partner, again that may not be a question everybody’s comfortable with or has time to ask that. Dr. Blayney, I want to ask you a very personal question for me. Do we have time to talk about that?

Those are some words people often use and that signal that “I need some help because this is embarrassing to me as a patient” and it may be embarrassing or something that’s not comfortable for me as a physician, as well. Giving some clues that we need to talk about something serious is inbounds and is inappropriate to be done.

Can a patient request a specific doctor?

That happens commonly. I deal with mainly breast cancer which is mostly a woman’s tumor. Some women would rather have a woman physician so that’s okay, I respect that. Nobody’s going to be happy if I’m forcing you to be my patient. There are nice, polite ways to do that and it won’t hurt anybody’s feelings.

So yes, if there’s something that’s not comfortable that you can’t work around, you certainly can. You have to do what’s in your best interests.

Remember if I have a long-term relationship with you as a patient, there’s a lot of things I’ve picked up on or that we’ve talked about that are difficult to convey to a new physician.

Advice to patients about how to build a relationship with the oncologist?

I don’t relate well to many people and I think that’s true of everybody. We learn techniques or workarounds along the way to help both parties get around that. I sometimes do better than others and it’s not a reflection on the patient or me.

What really helps is if you as a patient or somebody else, instead of being angry can take a deep breath and say, “Dr. Blayney, we’re not communicating well,” “Dr. Blayney I didn’t understand what you said,” or, “Dr. Blayney, could you say that in a different way – I’m asking for a friend.”

Advice to patients about balancing being a self-advocate and listening to experts?

There’s a fine line or tension between being overly aggressive and being passive. I think the most important thing that I stress is the value of time, both my time, my team’s time, but more importantly I don’t think patients want to spend all their time at the doctor’s office.

So being efficient about what questions you want to ask, if you’ve asked that four times, and I’ve given the same answer, I’ll tell you you’ve already asked that. But if not, I will sense it’s important for you.

Time is precious on both sides of the exam table so having a list and being efficient with that list is a great technique that I encourage patients to get into.

If you feel that I or any doc or any of the providers with whom you’re working aren’t answering your questions well enough or aren’t taking enough time, tell them that. We can make other arrangements. You may have to come back because there may be five other people also with serious concerns and problems waiting and we need to be respectful of their time, as well.

As I said, surprises often happen so we try to allow for them but sometimes we get surprises that take more time. As long as we have a plan going forward whether it’s coming back or maybe I’ll be back at the end of the clinic session we can talk through it, that’s okay, too.

In regards to advocacy, don’t be afraid to ask questions. Don’t be afraid to ask directions. If there are things you don’t understand, it may not be me, but there are people around who can help you and give you an honest answer.

I think that’s often a good way to start a conversation. Is there something I haven’t picked up on that’s important to you, if you want to make a different choice.

If I feel strongly about it, I’ll say but I usually listen to patients and if you’re not comfortable with it, I either need to make you comfortable based on my education, training, and experience, or I need to understand what’s really underneath your question.

» More: How to Be a Self-Advocate

How can oncologists improve the patient experience?

One of the things I’ve seen in my career is we’ve gone from paper-based charting or paper and pencil or pen notes to electronic health records.

One of the unintended consequences of that is I and other physicians and other members of my team often end up doing data entry tasks or checking boxes on the computer.

Because there’s only so much time in the day, we often turn our backs on the patients or convey that our intentions are more engaged in making a difficult computer interface work.

I think that’s a tragedy. It’s something in our profession we’re moving slowly away from as our computers get more in tune with our work flow. Everybody in life has cues that they use to tell somebody “listen to me now.” One technique: doctor I need to tell you this, I want to make sure you’re listening. Okay, I got it. I think it’s okay to do that.

Describe your experience at a smaller vs. larger hospital

At one point in my career I worked in private practice. I worked in a small hospital where I and one other doc were the only oncologists. I had a very personal relationship with the nurses and other hospital staff. I was the doc and my nurses around me in my office and in the hospital were the go-to people. So we had a more personal relationship with the patient and their families. There were certainly things that maybe I nor my colleagues, the surgeons, the pathologists didn’t have specialized expertise and we needed help.

So it’s not a sign of weakness in medicine or any other field to recognize when you’re out of your depth an you need help.

There are advantages to being treated at a smaller more personable setting, and also advantages to be treated in a large academic setting. I personally enjoy both settings and each setting is going to be right for one patient or the other.

The large hospital where I work now is big. It’s easy to get lost and often patients don’t see the same person each visit, or even on the same day if they’re in the hospital so it can feel a little large and impersonal here. But the reason we’re all here in a large place is there’s a concentration of expertise. I think in a lot of large hospitals where I work now, we endeavor to work more closely with our partners in the community and make those hand-offs when it’s best for the patient.

Any message to new patients?

One of the ways that we learn from patients and from cancer is from clinical trials. So [consider it] if you’re approached about being involved in a clinical trial either in a new anti-cancer treatment or a new diagnostic test or even some of the other side effects.

I’m doing a clinical trial now looking at neuro-cognition or “chemo brain.” It’s an interesting subject, something we don’t know a lot about but I think the larger message is that clinical trials are the way we learn about new treatments. It’s the way we know about treatments now that we’ve learned from patients who’ve gone before.

So one of the things I tell patients is that there’s not many good things about cancer but one of the good things is the opportunity to contribute the knowledge so that it can be better for the people coming after you.

What is the best part of being a breast cancer oncologist?

The part of the day I enjoy is opening the door and closing the door, knowing that we’ve solved together a patient, family and my team, problems that can be daunting at the outset.

Sometimes they’re simple solutions. Sometimes those solutions are complex and take a long time but knowing that we’re making progress toward a solution is what brings me satisfaction.

I also like the physical exam. Feeling lumps, feeling them go down over the weeks is very satisfying and gratifying. Also, I can bring to bear my experience and tell a patient this is what other patients in your situation have experienced.

Sometimes it’s helpful, sometimes it’s joyful, other times it’s really spooky but to know other people have been there before and sharing that is something that I take satisfaction from and enjoy.

What drew you into oncology?

Most doctors when they interview for medical school, they say I want to bring science to people because I enjoy science and I enjoy people. I think most people say that. I said that 40 years ago and for me it’s turned out to be true. I had some people that I respected who had cancer when I was growing up in high school and college and I wanted to help fix that.

I went into cancer many years ago because I could see we would be making progress. And we really have, so that’s what drew me to this field.

Thank you Dr. Blayney!

Ask An Oncologist

Dr. Christopher Weight, M.D.

Role: Center Director Urologic Oncology

Focus: Urological oncology, including kidney, prostate, bladder cancers

Provider: Cleveland Clinic

...

Doug Blayney, MD

Oncologist: Specializing in breast cancer | HER2, Estrogen+, Triple Negative, Lumpectomy vs. Mastectomy

Experience: 30+ years

Institution: Stanford Medical

...

Dr. Kenneth Biehl, M.D.

Role: Radiation oncologist

Focus: Specializing in radiation therapy treatment for all cancers | Brachytherapy, External Beam Radiation Treatment, IMRT

Provider: Salinas Valley Memorial Health

...

James Berenson, MD

Oncologist: Specializing in myeloma and other blood and bone disorders

Experience: 35+ years

Institution: Berenson Cancer Center

...