Does Roundup Cause Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma?

Expert witness Dr. Chadi Nabhan shares the true story behind the landmark Monsanto trials

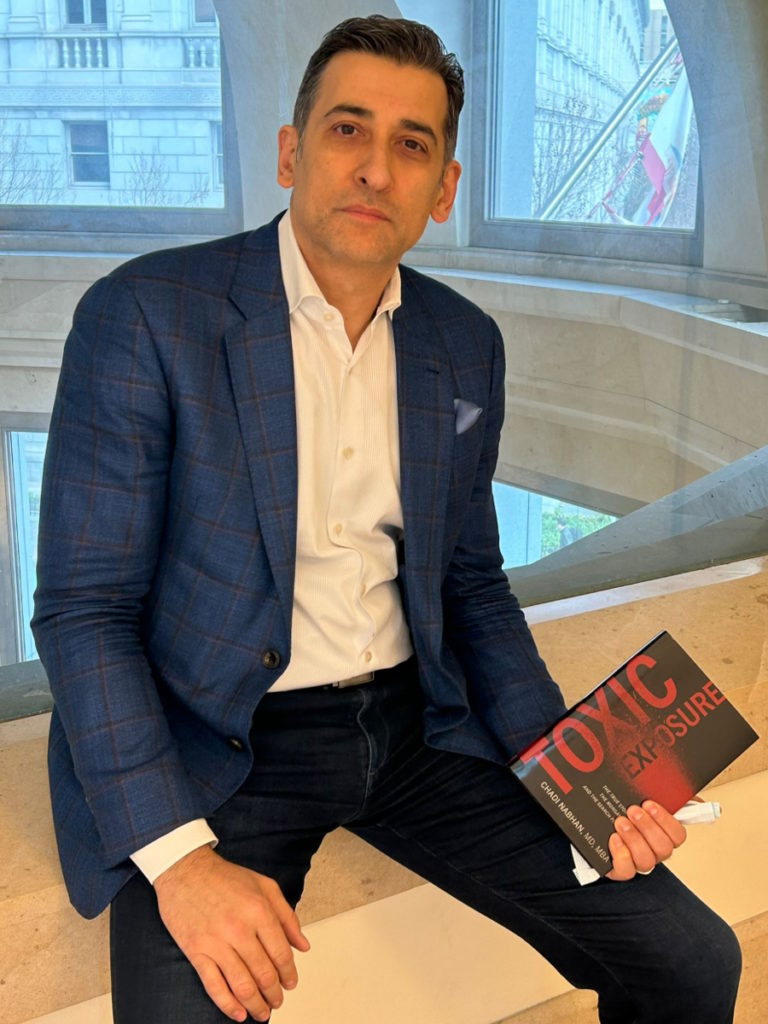

Chadi Nabhan, MD, a hematologist-oncologist specializing in non-Hodgkin lymphoma, served as the expert witness medical oncologist in the first three trials against Monsanto, the company behind the weed killer Roundup.

In this conversation, Dr. Nabhan shares how he got involved in the trials in the first place, what he learned from the trials, and why he decided to write a book about the whole experience.

- Background on The Monsanto Roundup Trials

- Introduction to Dr. Chadi Nabhan

- How did you get involved in the Monsanto trials?

- How much exposure to roundup is dangerous?

- What does it mean to be an expert witness?

- What have you learned from the Monsanto Roundup trials?

- How did you feel going on the witness stand?

- What was it like waiting for and then finally hearing the verdict?

- What guidance can you give to patients?

- How did you deal with the varying opinions and the difference in data?

- How can people assess their risk of toxic exposure to everyday products?

- Why did you decide to write a book about the Monsanto trials?

Background on The Monsanto Roundup Trials

In 2018 a school groundskeeper, Dewayne “Lee” Johnson, repeatedly used the Monsanto Company’s weedkiller, Roundup, and was later diagnosed with non-Hodgkin lymphoma. He claimed the diagnosis was because of the glyphosate-based herbicide.

Johnson’s case called nationwide attention to the possible dangers of toxic exposure. The lawsuit became one of the largest product liability lawsuits in U.S. history.

Johnson’s lawyers claimed the company not only knew the popular herbicide was linked to non-Hodgkin lymphoma, but also actively minimized its associated health risks.

Beginning in 1974, Roundup was touted as a safe and cost-effective solution to weed control. According to court documents, Monsanto continues to claim Roundup is “safe to humans.”

Since 2018, thousands of victims have brought legal action against the company.

Johnson won his trial and Monsanto was initially ordered to pay $289 million in punitive and compensatory damages which were eventually cut down to $21 million in an appeal.

Bayer, the massive German pharmaceutical company, purchased Monsanto for $68 billion in 2018. Following a wave of legal battles, Bayer agreed to pay $10.1 billion to $10.9 billion to settle current and future Roundup litigation. The company maintained “Roundup does not cause cancer, and therefore, is not responsible for the illnesses alleged in this litigation.”

Dr. Chadi Nabhan was an expert witness in three of the first Monsanto trials.

The Patient Story founder and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma survivor, Stephanie Chuang, interviewed Dr. Nabhan to learn more about his experience.

Introduction to Dr. Chadi Nabhan

Stephanie Chuang: Before we dive into the Monsanto Roundup trials, tell us a little bit more about yourself.

Dr. Chadi Nabhan: I’m a hematologist and an oncologist. I took care of patients for many, many years. I did a lot of work in non-Hodgkin lymphoma, taking care of patients as well as conducting clinical trials.

I was at the University of Chicago until 2016. I subsequently got an MBA in healthcare management. I became really very interested in the healthcare ecosystem.

I left the University of Chicago and took on various roles. Currently, I’m the chairman of the Precision Oncology Alliance at Caris Life Sciences. My role is really heavy on collaborative networks and big data collaboration and research across all academic sites and healthcare systems in the country. The hope is that this will really help [in] taking care of patients.

I’m also a podcaster. I have a podcast called Healthcare Unfiltered and I usually tackle a variety of healthcare topics, science, as well as what’s happening in policy and healthcare delivery.

“Medicine is the only profession where you are trusting somebody, who you’re probably meeting for the first time, [with] your health, the most precious thing in your life, at the most vulnerable moment.“

What drew you to medicine?

I actually was always more into journalism. I never thought I was going to be a doctor.

I was born and raised in Syria before I emigrated to the United States. In Syria, if you do very well in high school, you apply to medical school or law school. At the time, medical school was the most competitive. I was able to get into medical school, hesitantly, because my parents thought, and appropriately so, that it’s probably going to be a little bit [safer], future-wise and finance-wise.

As I got into medicine, I started liking it even more. There is a human element to medicine that does not exist in any other profession. Now, I’m not going to say that if you deal with a lawyer, somebody in the grocery store, or the person who does your hair [that] there is no human element.

Medicine is the only profession where you are trusting somebody, who you’re probably meeting for the first time, [with] your health, the most precious thing in your life, at the most vulnerable moment. That part of a human connection [is] what drew me into medicine more than science. Then science came along and I became very interested in scientific advances as well as human nature.

‘If I can learn anything from people who are diagnosed with cancer, I will learn humility, courage, and that human connection.’ That day, I decided I’m going to be an oncologist.

What got you into oncology?

When I was doing my residency at Loyola University Chicago, I met a woman who was diagnosed with ovarian cancer. She was in her mid-to late-40s. I was an intern just trying to get her vitals. Frankly, I wasn’t prepared to [answer] a lot of questions she may ask.

It was October 1995. I remember that day as if it was yesterday. She asked me, “Do you think I’m going to live until Christmas?” I was overwhelmed. I didn’t know what to say.

I got very emotional and I think she sensed that. She felt that she probably gave me more than I could tolerate and she actually said, “Don’t worry about it. I just hope to see your smile tomorrow.” In those exact words.

It was ’95. It’s 28 years later. To this day, I still remember her. I remember her daughters were sitting on the couch. I remember the event. I said to myself, “Wow. If I can learn anything from people who are diagnosed with cancer, I will learn humility, courage, and that human connection.” That day, I decided I’m going to be an oncologist.

I really believe the human nature of being an oncologist is one of the most important things. It’s a privilege for any oncologist to take care of people and to take care of patients. The scientific advances come after that, but at the heart of it is the relationship between patient and doctor.

I never really thought I was going to be an expert witness in this. I didn’t even know the magnitude of what I was getting myself into.

How did you get involved in the Monsanto trials?

Stephanie: That was so powerful to hear and I really appreciate that you approached it with such empathy. It really feels like you put yourself in the place of these people you’ve seen for many decades.

October 1995. That’s incredible that you remember so many details. I guess that does inform us of the approach that you’ve had as you were a doctor, as an oncologist, and what led you to [take] part in what became such a huge topic of these lawsuits about a weed killer that was causing non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

You’re a doctor. You’re seeing patients day to day. What got you into being one of these people who was testifying on behalf of patients against this weed-killer company?

Dr. Nabhan: As an oncologist and an expert in non-Hodgkin lymphoma, it is not uncommon to get calls [from] lawyers to look at malpractice cases or potential malpractice cases. I have always said no. I really never had an interest in this. I never had the time and I really never liked the idea.

Malpractice cases take away from the nuance of medicine because most doctors want to do the right thing all the time, but there are certain elements that really are important that could be lost in translation.

This was different. I never really thought I was going to be an expert witness in this. I didn’t even know the magnitude of what I was getting myself into.

Someone mentioned my name to a law firm in Virginia that was suing Monsanto for their weed killer Roundup, which is the most common weed herbicide used in the entire world. It is the one that is most used in the United States, obviously.

There was a report in March 2015 that glyphosate, which is the main ingredient in Roundup, is a probable human carcinogen and the most linkage was with non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

I was called by the law firm asking me what I think about Roundup and non-Hodgkin lymphoma and whether I would be willing to look at the evidence, evaluate the relationship, and render an opinion. And I did. I thought to myself, For the most part, we often don’t have an explanation [for] why someone has cancer.

When you get diagnosed with any form of illness, you ask, “Why? Is there something I did? Maybe I could have done differently?” It’s normal. Most often, we tell patients we don’t know either because we really don’t know or the science is not evolved enough to know.

But I thought to myself, If there’s a subset of patients that I could probably tell that maybe this was because of Roundup, then I would have helped that patient and their families.

We don’t know why lymphoma occurs in the majority of patients. Not every Roundup sprayer is going to get lymphoma and not every lymphoma is caused by Roundup. To me, it was maybe some patients who have used that hazardous compound developed lymphoma because of their use. If that’s the case, I want to be part of trying to help these folks.

I agreed after I reviewed the evidence and looked at everything. I thought to myself, I’m happy to help. I had no idea how big this was. I did not know what’s going to happen. I’ve never been in a courtroom testifying as an expert witness. In hindsight, I think it was foolish [that] I said yes because I was so overwhelmed, but it was probably one of the best decisions I’ve ever made.

Maybe some patients who have used that hazardous compound developed lymphoma because of their use. If that’s the case, I want to be part of trying to help these folks.

Stephanie: Why do you think it was one of the best decisions you’ve ever made?

Dr. Nabhan: Because I helped some patients. Did I help some patients? Yes. Did I play a small part in exposing the truth? Yes.

To this day, Monsanto will contend that glyphosate is safe and Roundup is safe. Sure, that’s lip service as far as I’m concerned. They can say whatever they want. And yes, they did a lot of settlements, saying, “We’re just settling this, but we don’t admit to any wrongdoing.” It is what it is. But what matters to me is that patients now are aware. People know.

We have scored some small wins. Monsanto is going to pull Roundup from residential use in 2023. The EPA (Environmental Protection Agency) is being asked to re-review the evidence. I think more people are aware of the harm of Roundup and what it could cause.

Whether Monsanto admits or denies it’s safe or not, as far as I’m concerned, more people are aware. We know that there’s [a] net harm to the compound in what it does to patients at large. And if I played a small role in this, then I’m proud of it.

Certainly, the trials were not won because of me. I’m just one person. There’s a team of experts way smarter than me. But I was part of this team and I played a small role. If I helped one patient and [was] part of [revealing] truth, then it was well worth the fight.

How much exposure to roundup is dangerous?

Dr. Nabhan: When you look at hazardous compounds, you have to ask do they provide net negative or net positive?

I know that [some] folks would say, “Look, my grandpa smoked two packs of cigarettes a day and he lived ’til 85 and he’s fine.” Sure. Maybe that’s the case in your grandpa’s situation.

But when you look at the entire issue of tobacco and smoking, is smoking causing net negative or net positive to people? I think that question is settled today. It’s net negative. You can still smoke, but it’s net negative.

I think it’s the same. Roundup is not going to cause lymphoma in every patient and not every lymphoma is caused by Roundup. Nobody will ever claim that. But is it causing net negative to people or net positive? And I will contend it’s net negative.

What does it mean to be an expert witness?

Stephanie: What does it mean to be an expert witness on behalf of patients? What do you feel were the most powerful parts of your testimony?

Dr. Nabhan: An expert witness is somebody who has developed expertise in a particular domain of medicine. In my situation, my expertise was non-Hodgkin lymphoma — what might cause non-Hodgkin lymphoma, how you treat non-Hodgkin lymphoma, the prognosis of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, all of these things.

An expert witness is somebody who is willing to evaluate the evidence in a particular case, in a particular litigation trial, and offer an opinion within the scope of his or her expertise.

I was asked to read the medical records of these patients, look at their past medical history, their exposure history, the treatment they got, the prognosis, and then render an opinion [on] whether I believe Roundup was a substantial contributing factor in these patients developing non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

I wouldn’t be able to testify in breast cancer, for example. It’s not an area of my expertise. I am an expert in non-Hodgkin lymphoma or all lymphomas in general based on my track record, publications, and scientific contributions.

I hope that facts are always the most important part [of] any trial. But in some trials, I actually think strategy trumps facts.

What have you learned from the Monsanto Roundup trials?

One thing I probably learned the most, which is pretty intriguing, is that the jury does not see all the evidence, which was pretty shocking to me as a citizen. I’m thinking, You’ve got these people. They’re sitting in a box. They’re spending a week, four weeks, or six weeks. You got to show them everything, right? You can show them everything so they can render an opinion.

It turns out that both sides fight over what they want to present to the jury. The plaintiff’s lawyers want to show everything that [will] help them win the case. Monsanto is going to say, “Well, no, you can’t show this.” They have motions, talk to the judge, and say, “Well, no, no, no, no.” Then the judge has to say, “We will admit this into evidence so you can show it to the jury,” or “You can’t admit this into evidence.”

Sometimes, a lawyer would say something and then the judge will say, “Ignore this. This is not something that you’re allowed to consider in your evaluation.” It’s pretty interesting. I did not know that this is the case.

There is a strategy in these lawsuits. The lawyers must really know their thing and they have to be convincing. The opening statements, closing statements, [and] the way they cross-examine are important. There’s so much strategy.

I hope that facts are always the most important part [of] any trial. But in some trials, I actually think strategy trumps facts. If you strategically know what you’re doing in some of these litigation trials, you may be able to win the jury to your side despite the fact that you may not be the truthful side.

I’m naive to the courtroom. I’ve learned also that I am very scared. I was trembling walking to the stand. I believe it didn’t show because I was trying to be composed, but my heart rate was going 120-130 beats a minute and, hopefully, folks did not realize how nervous I was.

My goal is not to really impress… My goal is to really win the jury and to make sure that the jury understands the facts.

How did you feel going on the witness stand?

Stephanie: Especially given that this is a huge company on the other side of this. It’s not some small defendant. Can you describe what it felt like? You talked about preparing the most you could possibly prepare. Going up on the stand, put us in your shoes in those moments.

Dr. Nabhan: I was very prepared. I read as if this is the biggest test of my life because I did not know what to expect.

I Googled every lawyer I was going to go against — as if this is going to help me. [That] actually made me more nervous. I knew that attorney counsel George Lombardi was going to cross-examine me in the first litigation trial. I Googled him and I was just petrified. The guy is an icon. He won Litigator of the Year. He’s just an amazing individual.

Frankly, he’s very respectful. He has a very calm smile to him. He connects with the jury well. He knows what he is doing. He’s very comfortable in the courtroom. I’m like, “Who am I to be able to even know what he’s going to ask me?” I was really scared. I didn’t know what to expect.

I didn’t know the magnitude of this. Monsanto has deep pockets. They were lawyered up. They had the best lawyers out there, but the team that was defending the patients was also very good. They were extremely good. They were dedicated, cared for their patients, [and] put a lot of time, effort, and money into it. I felt [that] I was in a chess match.

My goal is not to really impress Lombardi or even our lawyers. My goal is to really win the jury and to make sure that the jury understands the facts. So I was really very nervous.

I had no idea what to expect. I did not think that patients stand to win against this major corporation. It felt like David vs. Goliath. I really don’t want to give a lot of metaphors. I don’t want to blow things out of proportion, but it honestly felt like this.

You’ve got this large corporation that has never been taken to court for Roundup, was just bought [for] $63 billion by Bayer, the large pharmaceutical company, and so I was very skeptical [about] what’s going to happen.

But I’m very happy that truth prevailed and justice was served at the end [of] these three trials.

I know that trials [are not] really won by one person or lost by one person. But, to me, it felt personal.

What was it like waiting for and then finally hearing the verdict?

Stephanie: You’re part of history because you were part of the first three lawsuits. I even remember the day that I saw the headlines. This is such a big trial. What was it like to wait and then hear the verdict and to know that you were a part of it?

Dr. Nabhan: After the plaintiff rests, the defense starts to bring their witnesses and all of that. I was following this from afar. I live in Chicago and the trial was in San Francisco. I was following the reports and a couple of blogs and outlets just to see what’s going on.

It felt so personal to me. I know that trials [are not] really won by one person or lost by one person. But, to me, it felt personal. Maybe because I don’t do this commonly. It felt really personal.

When the defense rested, the jury starts deliberating. Every day, I would check in with the lawyers. I checked the outlets. The longer it takes to deliberate, the more anxious I was getting because I was thinking, If it was a slam dunk, they would have said [it] right away.

I really don’t remember exactly how long it took them, but I remember the date of the verdict was August 10, 2018. I was driving in the suburbs of Chicago. The judge announced that the jury has reached a verdict. I pulled over and I just keep refreshing my phone because I didn’t know where to find the news.

Everybody was watching the trial. It was the first trial so it was really taking a lot of attention. The verdict: guilty. $285 million [was] awarded to Lee Johnson. Of course, it went down afterward.

I cannot describe how happy I was. I was beyond happy because I was of the mindset that if we lost, we were going to lose because of me and if we won, we’re going to win because of the team.

I was the last witness on the stand for the plaintiffs. I felt so much burden that I was the one who was going to try to synthesize everything for that particular patient because the prior witnesses were talking in general [terms] — toxicology, animal studies, statistics, and so on. I was talking specifically about that patient.

It was such a relief because I felt that I did not fail Mr. Johnson. At the end of the day, what gets lost in translation between lawyers and all of these things is the person who is the most important and that is the patient.

I felt great. I cannot tell you how happy I am. It’s hard to describe my body language in the car when I actually was extremely happy, but it was like, “Yes!”

Stephanie: I bet it was incredible because there must have been some anxiety. Like, “How is this turning out? Did I communicate it in the way that I think I did?”

Dr. Nabhan: Absolutely.

I was beyond happy because I was of the mindset that if we lost, we were going to lose because of me and if we won, we’re going to win because of the team.

What guidance can you give to patients?

Dr. Nabhan: Ask questions. There is no question that it is stupid. This is your life and your health. You should be empowered to always ask questions. If your doctor is not willing to even entertain your question, get another one. The doctor is there to help answer your questions.

The way I would approach any case [is] by thinking: what do we know about what causes non-Hodgkin lymphoma? We already know that there are certain things that have been proven to be associated.

We have some viral associations. Folks with HIV positivity have [a] higher risk of developing non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

We know some bacterial associations. There are folks who have a form of lymphoma called MALToma, which is associated with the infection H. pylori, which usually happens in the stomach.

We know some drugs that could cause [an] increased risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Folks who are on immunosuppressive drugs, [which] bring their immune system down, could have [an] increased risk.

You see that in some autoimmune diseases. Folks, let’s say, who have Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis get medications that lower the immune system because, remember, these diseases are autoimmune. The immune system is very active and if you lower the immune system, you could actually have non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

There are other reasons why. I go through all of these reasons. I always thought that farmers have [an] increased risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma because of pesticide exposure. I admit I did not really have a lot of knowledge specifically about Roundup, but I’ve always known that pesticides and farming increases the risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

I go with the jury. I say, “I looked at this case. These are the risk factors in the Johnson’s trial [and] even in the Pilliods’ trial.” I had a whiteboard that I showed the jury and drew on. I said, “These are the risk factors. When we don’t find any of these, we call the cause idiopathic. Basically, we don’t know what causes it. The highest percentage [of] folks with lymphoma is usually idiopathic. We don’t know. But we have to go through these risk factors,” so that’s what I do.

I do [a] process of elimination. I say, “Well, Mr. Johnson or Mrs. Pilliod doesn’t have this, doesn’t have that, all of these things.” Then I’m left with one or two causes and I explain to them why I think this particular cause is the case.

Think of any disease again. I realize things are different. Somebody gets a heart attack. They go to their doctor. Why did they have a heart attack? The doctor says, “Okay, the risks of heart attack occur from high cholesterol. You don’t have that. From smoking. You smoke. Maybe that’s what it is.” Hypertension, diabetes, obesity. There are risks of heart attacks. If you eliminate all of them, you may tell the patient you had a heart attack and I actually don’t know why you had it. But sometimes, you know why it happens.

In any disease, as physicians, it’s almost like we’re investigators. You look at the causative factors that we know and you eliminate the ones that don’t belong to this particular patient and you keep the ones that belong. If you eliminate everything, then you don’t know why it happened.

Science is not perfect. Our job is to take care of patients and help patients despite imperfect science.

How did you deal with the varying opinions and the difference in data?

Dr. Nabhan: It is a big hill to climb. Science is not perfect. Our job is to take care of patients and help patients despite imperfect science. If you are waiting to get 100% confirmation of something, then you’ve never taken care of patients. You’ve never actually understood science.

Monsanto’s playbook has always been, “Wait a minute. Are you really smarter than the EPA?” I recall Mr. Lombardi in the litigation trial. The first one is like, “If we knew that the cause of this T-cell lymphoma or mycosis fungoides,” which is the disease that Mr. Johnson had, “if Dr. Nabhan is the only person in the world who has discovered it is caused by Roundup, he should have won some awards and something,” in a sarcastic manner.

You really need to peel the onion. You need to really open things up. How did the EPA really reach [its] conclusions? Did they actually follow the science? Did they actually do due diligence? Did they follow their own guidelines?

The EPA changed [its] position without any studies. At some point, they were thinking maybe it’s carcinogenic and then, suddenly, it became completely safe when we don’t know what happened there. But there’s some smoke and I don’t know. This was never proven in court, but there was a suggestion that maybe there’s some cozy relationship. You have to speculate and you have to ask the question.

My job was to ignore the noise and evaluate the science independently. We have a lot of examples in history where the EPA, the FDA, or the CDC has been wrong. The goal here is to really evaluate the science independently and make sure we serve patients.

Monsanto will always contend this. They will contend that they’ve done gazillion studies and all of the studies were safe, but they did not publish them because they are trade secrets. Great, we have to take your word for it. If you tell us it’s safe, then we’ll just believe you because [they’re] trade secrets. That really doesn’t make sense if you’re a patient that you think you really been harmed and that’s really important.

The toxicology studies were done by a lab in Northbrook, Illinois, called IBT Labs. And IBT Labs turned out to be fudging data. They actually were making up data. Some of the glyphosate studies done in that lab were completely wrong and other companies that use that lab also were harmed by this. The folks who operated the lab were eventually prosecuted.

They never repeated these studies. You’ve got some studies that said that its toxicology is fine. They really were fraud studies because the lab that performed them was a fraud lab. There [are] a lot of things that occurred.

It’s easy to say the EPA said it’s safe, but our goal is to really investigate whether the EPA did a good job and [whether] is it indeed safe or it’s not. If we don’t do that, we are not doing our job and our due diligence.

We have a lot of examples in history where the EPA, the FDA, or the CDC has been wrong. The goal here is to really evaluate the science independently and make sure we serve patients.

How can people assess their risk of toxic exposure to everyday products?

Dr. Nabhan: You have to look at the totality of [the] evidence. The only 100% proof would be if I take 100 people, put them in a room, and spray them with glyphosate and Roundup [then] put 100 other people in a different room, don’t spray them, and say, “I’m going to follow you both for the next 10 years and see who gets cancer or not.”

That’s not going to happen. It’s unethical. You cannot do a randomized controlled trial in a hazardous compound where you think you may induce harm.

What we are left with is what we have in terms of science, some retrospective studies, all of these things. You have to look at the medical records of a particular patient. Look at [the] risk factors this particular patient may have that led to the development of non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

What I’ve learned through the Roundup trials and through reviewing the evidence [is] that the more somebody gets exposed to Roundup, the more likely they are going to develop lymphoma. The higher exposure, the higher the risk. We have to take that into consideration in addition to the collection of evidence.

The totality of evidence is very important. What does glyphosate cause? We have a lot of data that glyphosate damages the cells, damages the chromosomes, causes cell breakage so it really induces some damage into the DNA of the cells and you know that this eventually leads to cancer.

We have animal studies. These animal studies that were reviewed showed that glyphosate, especially at higher doses, could induce certain tumors in mammals and humans are mammals.

Human studies were mainly epidemiological studies. [The] majority of them were retrospective. There was one study called the Agricultural Health Study that was more [of] a cohort study, which I describe in the book. It’s a study that Monsanto really likes because it suggested no association.

This was a study that Monsanto criticized before they knew the results. They just loved it after they got the results. They were afraid that the results will not be in their favor. It was like, “Oh, it’s a bad study.” Then the results came out. “Oh, it’s a good one. Let’s just tout that study much better.”

Patients really need to be their own advocates. Physicians need to evaluate the evidence. Most physicians are very concerned about the treatment and what [they] can treat patients with.

Same for me when I was called. One of the playbooks of Monsanto will be, “Dr. Nabhan, as you know, Mr. Johnson had many doctors, but none of his doctors, none of them, suggested that Roundup caused his non-Hodgkin lymphoma.”

Yes, because they did not investigate that. If you don’t really study the subject, you’re not going to find this out. Had they studied what I did, they would have found this.

That playbook is what the doctors did not really know because the doctors did not really study and evaluate the evidence. They just want to treat. Some folks are more interested in the treatment as opposed to anything else.

Ask questions. The doctor needs to, hopefully, understand the evidence. Maybe it’s related to Roundup, maybe it’s not. But I do believe that an expert healthcare professional needs to provide an opinion on that.

Why is Roundup still being sold?

Dr. Nabhan: At some point, smoking was fine. You had ads all over about smoking. Doctors in the hospital, seeing patients, were smoking. Patients were smoking [with] an oxygen tank by them. There are pictures of that. There are talk shows where the host and the patient were smoking cigarettes. It was acceptable.

We did not think it caused any harm. Both of my parents smoked at some point. We just didn’t know. Then science evolved and we found out it’s actually not good for you. It causes cancer and now it’s there. People know if they smoke, they are increasing their risk.

The same thing applies here. We may have thought it was safe 20 years ago. It is, in my opinion, counter-intuitive and counter-science to assume it is safe in 2023. I think we need to acknowledge that. At a minimum, we need to tell patients and put a label on it. Unfortunately, we don’t have that label.

But as a physician, as a human, as a patient, I would have loved to see a label. Use it if you want, but it is a probable carcinogen.

You are making a deliberate choice if you want to use something or not. If you do, at least you know you have to have very protective gear and make sure that it doesn’t really affect your skin or anything like that.

Why did you decide to write a book about the Monsanto trials?

Stephanie: What were you hoping will happen as a result of publishing this book and getting out there to the masses? And where can we find it?

Dr. Nabhan: I decided to write the book to really tell the stories of these three trials. I testified in Johnson versus Monsanto in state court, Hardeman versus Monsanto in federal court, and the Pilliods versus Monsanto in state court. These were the trials where I was the case-specific causation expert. All of these trials were won. [Dr. Nabhan is also the host and creator of the “Healthcare Unfiltered” podcast].

My goal was to describe the stories of these patients but also the stories of how I got involved in all of these litigations. What’s the story behind Roundup? Why it is actually being used a lot? It’s being used a lot because of the genetically modified organisms where the farmers can spray the weedkiller on their seeds and the seeds don’t die.

Monsanto is the manufacturer of both Roundup, the weed killer, and Roundup Ready seeds. You can now spray and harvest. No issues and we profit both ways. Roundup use increased exponentially starting in the mid-90s when the Roundup Ready seeds became available.

I wanted to describe how things evolved and what role I played. There’s a lot of courtroom drama, a lot of deposition issues, [and] a lot of history in the book. Bayer bought Monsanto. What happened after that? A lot of stories about these patients that really fought, the outcomes, and what happened.

My goal was to hopefully reach more people, to make them aware of the trials, to make them aware of Roundup, and the fact that Roundup is not good and it’s really causing harm. I’m hoping people are going to actually benefit from this. That’s really my goal.

The book can be found anywhere folks consume books. It’s called Toxic Exposure: The True Story Behind the Monsanto Trials and the Search for Justice. They can go to Amazon.com, Barnes & Noble online, [or] my publisher’s website, Johns Hopkins University Press.

I hope that the message will [reach] as many people as possible. I put a lot of effort into it because I really wanted to make sure that I described the facts so people almost see things the way I saw [them] like you were actually in my shoes. I hope the mission is accomplished.

Stephanie: It certainly sounds like a labor of love, not just the book itself, but what you did and committed yourself to some years ago. As a patient and advocate, thank you for all the years of work you did and for advocating for patients. I have no doubt that you played an instrumental role in these good verdicts for the patients. Thank you so much, Dr. Nabhan.

Other Medical Experts

Dr. Christopher Weight, M.D.

Role: Center Director Urologic Oncology

Focus: Urological oncology, including kidney, prostate, bladder cancers

Provider: Cleveland Clinic

...

Doug Blayney, MD

Oncologist: Specializing in breast cancer | HER2, Estrogen+, Triple Negative, Lumpectomy vs. Mastectomy

Experience: 30+ years

Institution: Stanford Medical

...

Dr. Kenneth Biehl, M.D.

Role: Radiation oncologist

Focus: Specializing in radiation therapy treatment for all cancers | Brachytherapy, External Beam Radiation Treatment, IMRT

Provider: Salinas Valley Memorial Health

...

James Berenson, MD

Oncologist: Specializing in myeloma and other blood and bone disorders

Experience: 35+ years

Institution: Berenson Cancer Center

...