The Latest in Colorectal Cancer Clinical Trials

What to Know about Common Misconceptions, Emerging Trials, and Biomarkers

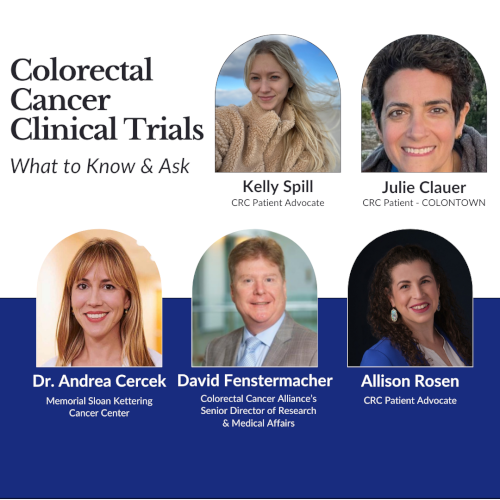

Edited by:

Katrina Villareal

What is it really like to find and participate in clinical trials as a colorectal cancer patient? Learn how to navigate the complex world of clinical trials from patients and experts who have been there.

Hear from Dr. Andrea Cercek of Memorial Sloan Kettering, David Fenstermacher, Senior Director of Research and Medical Affairs at the Colorectal Cancer Alliance, and patient advocates Allison Rosen, Julie Clauer, and Kelly Spill as they share the barriers, risks, and results from real-life clinical trial experiences.

*Watch the full video below!

Brought to you in partnership with Colorectal Cancer Alliance, Colon Cancer Coalition, and COLONTOWN.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider to make informed treatment decisions.

The views and opinions expressed in this interview do not necessarily reflect those of The Patient Story.

- Full Video Conversation

- Introduction

- Misconceptions about clinical trials

- Kelly’s clinical trial story

- Julie’s clinical trial story

- Deciding to join a clinical trial

- Clinical trials for young-onset patients

- Costs involved in joining a clinical trial

- Switching mindsets

- Importance of advocating for yourself

- Role of biomarkers in clinical trials

- Finding clinical trials

- Final takeaways

Full Video Conversation

Introduction

Allison Rosen: We’re going to talk about the latest in colorectal cancer trials, what to know, and what to ask. We’re going to hear from some experts in the field and some amazing patient advocates who have participated in clinical trials.

This discussion is hosted by The Patient Story, a platform where you can find hope, guidance, and supportive communities, explore insights on navigating life after a cancer diagnosis, discover promising treatments, and connect with people who truly understand what you’re experiencing.

I’m very, very excited to introduce the partners that help make this happen: Colorectal Cancer Alliance, Colon Cancer Coalition, and COLONTOWN. I’ve had the opportunity to volunteer with each and every one of them in one shape or form.

The mission of Colorectal Cancer Alliance is to empower a nation of allies and to provide support for patients and families, caregivers, and survivors. Their goal is to raise awareness of preventative measures and inspire efforts to fund critical research.

The mission of the Colon Cancer Coalition is to improve health outcomes by reducing barriers to complete colorectal cancer screening and educating the public to advocate for their own health through tailored, local, and grassroots solutions.

COLONTOWN is an online community of more than 120 private Facebook groups that provide education and peer support for colorectal cancer patient survivors and care partners on every aspect of living with colorectal cancer and beyond, including clinical trial understanding and experiences.

COLONTOWN has an amazing university that’s a public education resource with content created by patients and caregivers for patients and caregivers. It’s a library of original content where experts talk about various topics, including clinical trials.

The purpose of this conversation is to have a conversation. We want to humanize colorectal cancer clinical trials by hearing from people who have been through them and are now dedicated to advocating for others. We’re also going to answer questions and break myths that surround clinical trials in general but especially colorectal cancer clinical trials.

Allison Rosen

Allison: I’m a stage 2 colorectal cancer survivor and a very, very passionate advocate. I’ve worked in the field of oncology for about 17 years and have been an advocate ever since I was in remission.

David Fenstermacher

David Fenstermacher: I’m the senior director of research and medical affairs with the Colorectal Cancer Alliance. My role is to oversee our grant portfolio. I also work with the community to develop some patient-focused projects around biomarkers and equity. The other thing in my purview is a national survey, which we will be releasing later in 2023, for colorectal cancer patients and caregivers.

Dr. Andrea Cercek

Dr. Andrea Cercek: I’m a medical oncologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. I’m very passionate about clinical trials and the hope for the future that they give us.

Kelly Spill

Kelly Spill: I was diagnosed with stage 3 colorectal cancer at age 28. At that time, I had an ulcerated 5 cm tumor and I received nine infusions of immunotherapy from March to August 2020. I was declared in remission that same August.

Julie Clauer

Julie Clauer: I’m a stage 4 colorectal cancer patient. I was diagnosed in March 2018 with liver mets and since then, I’ve had cancer jump throughout pretty much everywhere — lung, liver, lymph nodes, bone.

I’ve had an active disease since then and started participating in a clinical trial in July 2020. I was on the trial for two and a half years and it completely changed the trajectory of my disease. I might actually have my first scans with no evidence of disease. We’re hoping that after all these years, I’m finally NED.

All the drugs that we have now were at one point in a clinical trial and had to be tested on people in order to get approval.

Dr. Andrea Cercek

Misconceptions about clinical trials

Allison: I’m very, very excited because this is such an important conversation. People have all sorts of knowledge about clinical trials when they go in. When we talk about clinical trials, there are a lot of misconceptions.

Dr. Cercek, what are some misconceptions you’ve heard? When people reach out to me, one that I’ve heard is they think clinical trials are a last resort, only for the very sickest patients. But they aren’t, are they?

Dr. Cercek: No, definitely not. Clinical trials come in all shapes and sizes and in all stages so that’s a really, really important point. People often feel it’s a last resort. “I’m a guinea pig. Why should I do this? Will this matter at this point?”

Trials happen in early-stage disease. They can be as a first-line treatment, when someone is first diagnosed, and also with advanced disease, where the goal of the trial is how to improve the standard treatment either by adding new medication or changing medications completely based on data from studies in advanced disease.

It’s important to run these trials in all stages to find out which drugs work and at what stage they work best. That’s a really, really important point that we need to instill. It’s critical for people to consider clinical trials because that’s really what helps move science forward. That’s really what makes advances.

All the drugs that we have now were at one point in a clinical trial and had to be tested on people in order to get approval. We have super strict approvals for all drugs but especially for oncology drugs. We get approval through clinical trials.

Patients are afraid they’re going to be given a placebo. In oncology, that’s not true.

David Fenstermacher

Allison: That last point is one of the things that most people have no idea about. David, you speak to patients all the time. What are some of the questions and misconceptions about clinical trials that you hear?

David: The one I hear the most is patients are afraid they’re going to be given a placebo. In oncology, that’s not true. The care that you would get would be the standard of care for your disease at your particular stage and biomarker. That’s really important to understand.

There are all sorts of concerns that patients have. How do I find a trial? Is there a trial near me? What are the costs of a trial and who pays for the different aspects of that? If you participate, how is that going to alter the schedule of when you have to go to the doctor or the site where the clinical trial is being conducted? Do you need more tests? Do you need more imaging?

A lot of people don’t truly understand that when you go in, it’s very regimented. You will learn exactly what’s going to happen. You can ask questions of your doctor so that you can understand exactly what you’re getting yourself into by possibly participating in a trial.

Everything is your decision. You can withdraw from a clinical trial at any time. This is really about you and the care that you can get through these new therapies or new combinations that are being developed.

Allison: This is great information. If someone is in North Carolina, they want to go to Houston or New York for a trial. They want to go to the trial that’s best for them. They want to know about cost, lodging, parenting — all the different things.

I said, ‘You know what? I have nothing to lose. The side effects sound a lot less worse than chemo, radiation, and surgery. Let’s give it a shot.’

Kelly Spill

Kelly’s clinical trial story

Allison: Kelly, we want to hear about your clinical trial experience. What were your first treatment options and how did you end up hearing about clinical trials? Did your doctor bring this up or did you?

Kelly: My original treatment option was chemo, radiation, and surgery, which would have led me to have a colostomy bag for the rest of my life and likely not be able to carry another baby again.

I didn’t know anything about clinical trials. I’m actually still learning to this day and it’s very exciting to learn now that I’m in remission. I’m in a big learning era right now.

At the time, I was going to Memorial Sloan Kettering. If I didn’t go there, I would have never known about this clinical trial.

I was planning on checking out a couple of cancer centers at the time and once I hit Sloan, I felt like I was at home. I felt like a family member there. I felt very comfortable. They were very informative with everything that was going on and that I needed to know.

Thankfully, I had a research nurse come into my room right before we were about to set an appointment to start chemo. She said, “We may have another option for you. Would you like to hear it?” I said, “Of course, I want to hear another option.”

I had this other option specifically because my tumor type was an MMRD, mismatch repair-deficient, so it allowed me to be on this clinical trial.

I had my mom with me and I don’t know what I would do without her. It was really nice having someone with me who was able to understand what I was being told. Being so sick, not feeling well, and being young, I had no idea what a lot of these big words meant and what was going on at the time.

After I heard the pros and cons of the side effects, I looked at my mom and asked, “Should we do this?” She asked, “How do you feel about it?” I weighed out my options.

I said, “You know what? I have nothing to lose. The side effects sound a lot less worse than chemo, radiation, and surgery. Let’s give it a shot.” If that didn’t work for me, then I would have gone back and did the chemo, chemo-radiation, and surgery. I still had a backup.

Allison: Having a caregiver there is so important, someone you trust and know. We’re in a nervous state and going through something very, very traumatic so having someone else there to help guide you is so important. Thank you so much for sharing and letting everyone know how you came to that decision because it’s personal and hearing different viewpoints is so important for others.

Dr. Cercek, you co-led the trial that Kelly was on and know her well. Can you tell us a little bit more about this trial?

Our trial was specifically asking the question, ‘Can it work even better when the tumor is in an early stage when it’s localized before it spreads?’

Dr. Andrea Cercek

Dr. Cercek: This study is still open. It’s for patients with mismatch repair-deficient, a specific subtype in early-stage rectal cancer.

Normally, for early-stage rectal cancer, the treatment is chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery. Because it’s located down in the pelvis at the end of the large intestine, there are a lot of important organs that are affected by our normal treatment, like the ovaries and the uterus.

Although it’s a good treatment and it’s curative, people are left with a lot of toxicity from treatment, including not being able to have babies, bowel/bladder dysfunction, and potentially even a permanent bag in about a third of patients or so because of where the tumors are.

The idea of the study in this subset of patients with mismatch repair-deficient or MSI-high tumors is to try immunotherapy. We knew that in stage 4 disease, immunotherapy works very well for mismatch repair-deficient colon and rectal cancer. This was accomplished in a clinical trial where it was the same idea.

We have a good biomarker. Our trial was specifically asking the question, “Can it work even better when the tumor is in an early stage when it’s localized before it spreads?” The way that we designed it is that because the standard treatment was curative, we didn’t want to compromise the cure.

We gave immunotherapy first, watched the patients really closely, and then if the tumor didn’t completely go away, they would simply jump onto the normal standard of care regimen with chemotherapy, chemo-radiation, and surgery, depending on the clinical situation. Everyone would be offered a complete package.

Thankfully, we saw that immunotherapy alone is able to get rid of these tumors so it’s been really amazing. Now we’re treating all different early-stage cancers, including the esophagus and stomach that have mismatch repair deficiency or MSI High. As I mentioned, the rectal study is still ongoing.

Allison: It’s important to note that that trial was for that specific gene. It’s important to know your genes and your mutation so that you can figure out what trial works best for you. Talk to your doctor about that so you have that knowledge. I’ve heard about your research and now meeting Kelly and seeing the human side of it is just amazing. Thank you so much for doing what you’re doing and continue doing what you’re doing.

I’d had over 60 chemo treatments, five open surgeries, and multiple radiation therapies. My body was worn out.

Julie Clauer

Julie’s clinical trial story

Allison: Julie, we want to hear about your clinical trial experience. How did you learn about it and how much did you know before?

Julie: In my first appointment before I started treatment, I was told about a clinical trial. I thought that was just what happens is that you get offered clinical trials. I found out later that that’s not actually how it works.

At that time, I decided not to do the clinical trial. I knew with stage 4 and as extensive as the disease I had, I knew that the first line of treatment wasn’t going to work forever and I knew that this wasn’t going to be a one-shot deal for me.

I’m a planner by nature so I wanted to know what the options were before I needed them. It was actually while I was doing well in treatment that I did the most research on clinical trials. I felt like that was extremely helpful because I wasn’t in a panicked state. You’re looking at it very objectively. You’re not making a major life decision at that point.

Sometimes I’d find out about clinical trials from COLONTOWN. I’d hear about something from another patient or my doctor would tell me about something he was working on that was really exciting.

We dribbled the clinical trial conversation in which I’d bring something to an appointment and say, “I heard about this trial. What do you think?” I’d get his opinion. It was like talking and learning about clinical trials two minutes at a time over a long period of time.

Anytime I got news of progression and needed a treatment change, we’d already have a set of what would be next. I always wanted to have a few options. The clinical trial I ended up going on was always on that shortlist.

When I would come in with the results of a scan that wasn’t good, we’d say, “Given what we see now, are all those still options? How do we want to move forward?” We had already made the decision before I needed the decision.

This trial was one that was on the docket for a long time so I learned a lot about it. I learned how the early results were going. I learned almost too much because, by the time it was time to go on it, the trial was not looking very good in terms of the results. From a research perspective, it didn’t meet its endpoint.

But I had progression and I was really exhausted. I’d had over 60 chemo treatments, five open surgeries, and multiple radiation therapies. My body was worn out.

When it came time to decide what was next, I could have gone on the last line of the standard-of-care chemotherapy, a third-line treatment that was available, or two trials that were in the mix.

This trial was one that was on the docket for a long time so I learned a lot about it.

Julie Clauer

When I went to my doctor, we were talking about the trial that I ended up going on. It was a better option for me than the standard of care at the time. We talked about the fact that it wasn’t going to change the trajectory of my disease. I wasn’t going to be cured, but the short-term stability was pretty good.

He said, “It’s immunotherapy-based. The toxicity is less. It could give you a few months to regroup, have a chemo break, and hopefully get you to stability so we could figure out what’s next.” It was intended to be a bridge.

I said, “Okay, I think I want to do this, but we have that other trial that I’m more interested in so I want to go talk to that primary investigator.” He was at a different institution. I made an appointment with him, talked to him about the trial, was excited about it, but he said, “It’s not open for another six weeks and when I look at your counts, you’re not going to be able to wait that long.”

There’s also an element of having options because you don’t know what will be available and what will work for you. I was looking for a range of stability and I ended up being stable on it for two and a half years.

It opened up a lot. I was able to get surgery. It was much better than stable, in my opinion. In terms of the actual results of the trial, it was stable. It goes to show that you have to know what you’re looking for and have some options.

Those moments are scary. Having somebody else who can help talk you through it is fantastic. Not having all the information thrown at you at a time when you’re really scared and trying to figure out the logistics while you’re in the moment was key for me.

My clinical trial experience was fantastic. It out-delivered. I actually went off the trial to get surgery, which wasn’t an option before. My side effects were significantly better.

I’ve since gone on an off-label treatment because of how I responded to the trial. It became an option because of how I did. It really changed everything about my disease, but it definitely was not the cure.

Allison: It’s always very complicated. It’s never, “I’m going to do this then this and this.” You need to figure out what’s best for you at that time. Sometimes you have to wait or make a difficult choice about where to go next if one trial doesn’t open for a certain amount of time. Someone asked, “What exactly do you mean by stability? No tumor growth?”

Julie: No tumor growth. Technically, on a clinical trial, if you have between 30% shrinkage and 20% growth on certain tumors that they’re measuring, that means stability. Technically, I had stability. However, I had 29.4% shrinkage so I was right on the cusp. I had 11 mets and went down to four. I was nonsurgical and became surgical.

Those outcomes are so important for researchers to look at, to see the whole population and how people do to move medicine forward. But when you’re an individual patient, I think all that matters is what it means to you.

Deciding to join a clinical trial

Allison: You can see between these women that their stories are different. Trials are different and they’re happening all over the US. There’s a process and some people might not know the process. How do I find what’s best for me? What might go through the mind of someone thinking about a trial?

Kelly, what was the process like for you before deciding to join the trial? Did you have any concerns? What were some of the questions that you asked your doctor?

Kelly: To be honest, I was so sick sitting there that I was weighing out the side effects. I was so concerned about not being able to have another baby. I was so concerned about radiation.

I remember sitting and listening to what I would have experienced as side effects. My sex life would have never been the same. It really scared me. Radiation and surgery scared me a lot more than chemo at that time.

After hearing the side effects of this clinical trial, I said, “Why wouldn’t I try this?” I had a backup plan of chemo, radiation, and surgery. My mom and I looked at each other, I said, “Let’s go for it.”

I’m the only one in my family who has been diagnosed with colorectal cancer. No one in my family has cancer so I haven’t been surrounded by it. I didn’t know anything. In our eyes, it was more of a chance of should we do it or not.

Coming out of this, I want to be that advocate because so many young people are being diagnosed with colorectal cancer. If you don’t know anyone who goes through it, you don’t even know that there are any of these options or resources.

Keep an open line of communication at every point. Make sure everyone is informed that these are the possibilities that we might be thinking about at some point.

Dr. Andrea Cercek

Clinical trials for young-onset patients

Allison: We know early-onset colorectal cancer is on the rise. I was an adolescent young adult patient when I was diagnosed. I wouldn’t say epidemic, but there’s something going on. Researchers and oncologists are trying to figure out why.

There are a lot of young onset programs now. How do oncologists proactively counsel their patients about trials given most young-onset patients want to do trials before failing the second line?

Dr. Cercek: Epidemic is actually a really good word. It’s rising worldwide. We don’t know why it’s happening, but there’s a steady rise from year to year.

We opened centers dedicated to young people under the age of 50 with colorectal cancer for two reasons. First is for research to try to get data to figure out why this is happening and second is to help patients navigate this disease from diagnosis through treatment and into survivorship. Each stage is critically important and has different and unique challenges in our young patients, as everyone here is well aware.

We believe that this disease, as best as we can tell, is the same disease once someone has it. There might be slight nuanced differences, but in terms of available treatment, our chemotherapy and our trials are for all ages. There’s nothing specifically for early-onset colorectal cancer because the disease, once it’s present in any stage, behaves very similarly.

Young patients themselves are more motivated, perhaps more eager to participate in trials and think about the next steps. It depends on the person very much, but that’s probably true as a group.

Although someone is motivated, it’s not always easy to offer trials because sometimes the standard of care is better, which is an important thing to acknowledge and think about, too. We have certain good treatments that are already accepted as the standard of care.

There are trials for every stage so it’s an important thing to keep in mind, especially with our young patients. Often, people come armed with information.

It’s incredibly overwhelming how many trials there are out there so that’s a challenge in and of itself. It’s important to educate our patients at any age, but especially our young patients in terms of biomarkers, which are potential targets in the future.

If someone has a specific mutation, I’ll often say, “Listen, you have this. We’re not going to think about this now, but this might be something that we’ll think about a trial in the future,” or, “There’s an exciting new trial with combination immunotherapy. We don’t need it right now, but that’s something that we’ll think about.”

The challenge is always, “I’m ready now, I’m ready now,” and oftentimes, I’ll tell you, “Listen, you’re in a really good spot. You don’t need anything right now because we don’t have anything. The chemo that you’re on is actually working. Once, of course, we see that it’s not working, then we think about what are the next steps.”

The most important thing is to keep an open line of communication at every point. Make sure everyone is informed that these are the possibilities that we might be thinking about at some point.

Allison: Having an open line of communication is huge as well as trust. Patients can do their research but it’s shared decision making. It’s about what’s best at that time. Younger people might be eager, but we have to trust in the process.

You shouldn’t let cost, fear, or other things stop you from investigating and thinking about trials.

Allison Rosen

Costs involved in joining a clinical trial

Allison: Does insurance cover clinical trials? People can’t just pick up and go. There might be a trial down the street, but the best trial might be 500 miles away or a thousand miles away.

David: There are some things covered by the sponsor of the clinical trial. The study drug is covered. Any lab tests related to any endpoints that aren’t the primary endpoint are paid by the sponsor. Any imaging that the sponsor would ask to be done so that they can monitor the response to the therapy on the clinical trial very closely would also be covered by the sponsors.

The doctor’s visits, hospital stays, regular lab tests, and regular imaging that would be part of the standard of care, your insurance would pay for.

Some sponsors do provide support for things such as transport, housing, food, and child care. There are other resources like the Colorectal Cancer Alliance, where we also have resources where we can help patients with some of these financial needs.

We have navigators who can help you through the process of finding a clinical trial and how you can participate in a clinical trial based on some of the challenges that you have.

Allison: You shouldn’t let cost, fear, or other things stop you from investigating and thinking about trials.

I wasn’t giving up on the idea of a cure. I saw it more as a relay race.

Julie Clauer

Switching mindsets

Allison: Everyone wants to be cured and it’s hard not to be stuck on getting to a cure. Julie, how did you change your goal to stability? What was that like?

Julie: It depends a lot on where you are in your care. That changes every point. Overall, the long-term goal and desire is always cure.

When you look at where I was in treatment, I was on the third/fourth-ish line. My body was very depleted. My blood count numbers weren’t doing so well. My platelets were low. I wasn’t necessarily in a healthy spot to do trials.

One of the reasons why I couldn’t wait six weeks wasn’t because the cancer was out of control. It was because I probably wouldn’t be healthy enough to participate in a clinical trial. That’s another reason not to leave them as a last resort.

But at that moment, I wasn’t giving up on the idea of a cure. I saw it more as a relay race. For this segment, what I want is to get to stability, to be able to regroup, let my body recover a little bit so I can figure out the next step.

Any given treatment, if you look at it as a one-time treatment, depending on where you are in your disease, you could be cured with one treatment like Kelly was. Where I was in my disease, I knew it was going to be a series of multiple treatments.

Look at it as segments of the long race. In this segment, what I was looking for was stability so that I could be ready for the next segment. My goal would change then because if I’m stable, then my goal would be something different at the next point.

Allison: Clinical trials are a conversation and decision you make with your care team, your caregiver, and yourself. You have to think about a lot of different things. It’s not an easy decision.

Stay in contact, be honest with what’s going on, and be honest with yourself. If you have a question, ask. Don’t be scared.

Kelly Spill

Importance of advocating for yourself

Allison: Kelly, you mentioned your mom was a part of your decision making and you now strive to be an advocate to help others. What advice do you have for people as far as being their own best advocate when you’re talking to your care team?

Kelly: Before I started the trial, I was taking pictures of what was happening in the bathroom because sometimes it’s hard for me to describe what’s going on. I took pictures and showed my oncologist.

I ended up being very close with my oncologist and my research nurse. They were calling me pretty much all the time. I don’t know if that’s how it is in every hospital, but I was taken care of very closely.

We had a very open communication. I wasn’t holding anything back. I told him how I felt after every treatment, every little detail, not just physically, but mentally and emotionally. All of that plays into it.

As a mom, my mind is elsewhere, too, so I was writing in my Notes on my iPhone how I was feeling at home.

I was constipated a lot and not doing well. After my first or second treatment, I couldn’t stop going to the bathroom. It was a completely opposite problem that I had been having. I quickly called the research nurse and told her what was going on, and she said, “That’s actually great news. Everything is being released.”

Stay in contact, be honest with what’s going on, and be honest with yourself. If you have a question, ask. Don’t be scared. It’s easy to be scared when you’re going through something like that, but putting everything out on the table is important.

Allison: I didn’t think about taking pictures. A journal can help because you go through so many things and can’t remember everything. You only have a certain amount of time with your doctor so coming prepared with a list helps expedite the conversation, help them understand, and not forget something. Be as prepared as possible. Those are great tips.

When people are first diagnosed, it’s really important to know those biomarkers right away.

Dr. Andrea Cercek

Role of biomarkers in clinical trials

Allison: Dr. Cercek, can you talk about the role of biomarkers in clinical trials and how they can guide personalized treatment?

Dr. Cercek: A biomarker, at this point, is probably one of the most important pieces of information in terms of clinical trials and general treatment of colorectal cancer. It’s definitely important in advanced disease and even in the early stage, as we saw from Kelly’s experience.

A biomarker basically is a change in the tumor, like a mutation, which we have a potential drug for. Important biomarkers in colorectal cancer are things like mismatch repair deficiency or MSI, where we can use immunotherapy or other combinations that are tested in clinical trials.

Important biomarkers include BRAF, V600E in particular, but BRAF is good enough to remember. We’ve made progress with BRAF targeting in clinical trials. There’s an approved therapy, but we’re trying to do better. It’s a really, really important marker in terms of treatment and trials as well.

Another one, which used to be a huge challenge but now we’re making progress, is KRAS or RAS. Typically, when we hear RAS mutated, we think there’s a treatment that we can’t use, like anti-EGFR therapy.

Now, there are RAS inhibitors or RAS-targeted therapies. RAS is the biomarker and then we have a targeted therapy for different types of KRAS. You might have heard KRAS G12C; that’s the new kid on the block. We recently had very good data in terms of responses when treating this biomarker in colon cancer. A newer one is G12D that’s now in clinical trials.

That’s an important thing to think about and to test. Most importantly, it’s something that everyone should have done when they’re diagnosed so that we know what the landscape is and what we can do, not only in terms of clinical trials but also the standard of care.

Another really important one is HER2 or ERBB2. We’ve studied that a lot in breast and stomach cancer, but now we’re seeing combinations work in colon cancer as well. There are ongoing trials looking at it in advanced disease and first-line treatment.

When people are first diagnosed, it’s really important to know those biomarkers right away. We’re also looking at it in early-stage disease and rectal cancer, similar to the study that Kelly was on but with HER2 targeting because it’s a very, very good biomarker for which we have a really good drug.

There are a number of biomarkers that we need to know. We encourage the next-generation sequencing of the tumor to know the mutational landscape. You can do it from the tumor. We could even do it from the blood in what’s called circulating tumor DNA. There are different ways to get it done, but it’s important for everyone to speak with their oncologists and have that done if you don’t already know that information.

Things have changed over the past few years in such an exciting way so you can treat the specific mutation of the tumor of that person. Asking those questions is one of the most important things.

Allison Rosen

Allison: The point that you made right there is so important. Not everyone has the knowledge. Ask about biomarker testing and circulating tumor DNA. Personalized medicine is so important now. Back when I was diagnosed, the standard of care was chemo, radiation, and surgery. A lot of this was on the horizon.

Things have changed over the past few years in such an exciting way so you can treat the specific mutation of the tumor of that person. Asking those questions is one of the most important things. A few years ago, only one mutation had a trial. Now there’s all this research ongoing. There are trials ongoing for a lot of this. Have that conversation with your doctor.

If you don’t know, that’s the first question you can ask your care team. Send them a message or call their team.

If they haven’t done it or they haven’t told you about genetic testing, biomarker testing, or circulating tumor DNA testing, have that conversation. It could change the trajectory of your whole treatment. You can find a trial that would work for you.

Julie: Biomarkers are so critical. As a vanilla girl who’s wild type with no targetable mutations, not having a mutation is valuable information as well. There are a lot of trials that are available to you, too. A lot of people will say, “I don’t have any of those mutations so I’m out of luck.” No, you are not and I’m proof of that right here.

Dr. Cercek: Julie, thank you for that point. There are many studies, many drugs, many trials, and many different ways of targeting colorectal cancer. Biomarker is just one of them.

There are different ways that drugs can enter the cell that have nothing to do with the mutation that are also explored and making progress. That’s really critical to know your mutational landscape because even that wild type makes a big difference in the standard of care, too.

Allison: The amount of information that’s being shared here is so valuable.

There’s a wealth of tools on the Internet that can help you find a trial. It’s more about making sure you’re finding the right trial that is also going to fit your lifestyle.

David Fenstermacher

Finding clinical trials

Allison: How do you get started on a trial and/or find trials and register? How often should a patient be searching?

David: ClinicalTrials.gov was brought up, which is a website run by the government that lists all clinical trials available. That can be a little bit daunting to navigate through. It’s a fairly complicated site, but that’s the place where you’re going to get the most. You have to use different search strategies.

There are tools out there that you can use. You don’t have to necessarily do it yourself. We have a system called BlueHQ. It’s a patient portal that allows you to learn more about your disease, especially if you understand your biomarkers. We have a trial finder embedded called Leal Health. You can put data in there and they will try to match you with a clinical trial.

I’ve worked at several comprehensive cancer centers and they will have on their website what clinical trials are available. There’s a wealth of tools on the Internet that can help you find a trial. It’s more about making sure you’re finding the right trial that is also going to fit your lifestyle.

ClinicalTrials.gov is going to be the most up-to-date because protocols have to be submitted to ClinicalTrials.gov. You don’t have to do it yourself.

We use something called Leal Health that you can get through BlueHQ that allows you to enter data into their platform and they will try to do the trial matching for you. They’ll contact you if you are eligible for a trial, talk to you about where the trial is being conducted, and then see if you’re interested.

There is so much going on right now in colorectal cancer. When you look at new types of drugs that are coming out, antibody-drug conjugates are one. Think about new immunotherapies and how to turn cold tumors, those that do not respond to immunotherapies like PD-1 and PD-L1 therapies, into hot tumors so that they would respond then to those immunotherapeutic drugs.

There are opportunities for things like oncological vaccines. If you’re in stage 2 or 3 and you have a resection done, a company will take your tumor, sequence it, and look for neoantigens. These are caused by mutations in the tumor.

The interesting thing here is is they give you a vaccine against most common neoantigens so that hopefully if you grow new tumor cells after your surgery, your immune system would already be primed to take care of them.

On a daily basis, there could be a new trial. It’s more important to work with your oncologist and let them know you’re interested so they can help with trying to find the right trial for you.

Not all oncologists are comfortable with clinical trials, especially in rural parts of the country. There are resources that you can reach out to online that would allow you to keep track of clinical trials more closely. You can work with other companies that can do clinical trial matching for you. They’re on the web so they’re available.

Work with your oncologist and let them know you’re interested so they can help with trying to find the right trial for you.

David Fenstermacher

Final takeaways

Dr. Cercek: The most important thing is you can be and should be your own advocate. Speak up for yourself. Open that line of communication.

If you’re having trouble, let your oncologist know. If you have questions, it’s okay. Ask questions. It’s not annoying. You’re in this fight together and that’s the most important way to think about this and to approach this disease.

Kelly: Ask questions. Be open. You know your body best and you know yourself best. Coming from someone who’s a big introvert, I always feel like I’m annoying people with all these questions. It’s so important to ask them. Trust your gut.

David: A clinical trial could be out there that is just right for you at your stage in your disease progress. Do not be afraid of the fact that it’s research. These are drugs that have gone through extensive pre-clinical testing. This could be the best standard of care that you could get. Keep an open mind.

Julie: There’s no perfect trial for everybody. They’re all studies. They’re all trying to learn. Know yourself and have those conversations. Understand what you’re willing to do before you need to make the decision. When you get to that point of having to make the decision, you don’t necessarily have enough time to make the best decision you can.

Allison: Thank you so much to these panelists for their time to share and educate. You will most certainly help save lives by being here to share so thank you to each and every one of you.