Shared Treatment Decision Making

Dr. Babis Andreadis

Dr. Babis Andreadis is a well-known face in hematology-oncology, who’s spent more than 20 years treating cancers like lymphoma, leukemia, and myeloma.

In his interview with The Patient Story, Dr. Andreadis talks about shared treatment decision making, whether patients should ask for second opinions, guidance on how to approach patient self-advocacy, and addresses most common patient and caregiver questions.

- Name: Dr. Babis Andreadis

- Role: Oncologist

- Specialty: Blood cancers

- Experience: 20 years

- UCSF (current)

- University of Pennsylvania

- Approach with patients: Direct, clear communication about everything from the treatment plan to quality of life issues, including fertility.

My role is going to be to help guide you through this process, help you make the best decisions for yourself, and help you fight the disease that you’re dealing with in the way that best works for you and your family.

I want you to feel free to see me as your guide through this process.

Dr. Babis Andreadis

- Dr. Babis Andreadis Introduction

- What inspired you to become an oncologist?

- Describe what your typical work day looks like

- Take us through your days at clinic

- Advice on whether patients should get a second opinion?

- How can patients find those experts?

- What is the "survival rate" in layman's terms?

- Can patients work through cancer treatment?

- Relationship with Patients

- What is it like meeting new patients?

- How different are patients?

- Advice for patients on hitting the right balance (of opinion) with the doctor?

- What are common questions from patients?

- Are there questions patients should be asking?

- What are the top hot topics that come up with patients?

- What do you tell patients about engaging in sexual activity?

- What do you tell patients about fertility?

Dr. Babis Andreadis Introduction

What inspired you to become an oncologist?

I entered medicine in an era where a lot of the scientific discoveries were kind of starting to take place, especially the field of molecular biology. A lot of medicine I think of as physical in terms of doing surgery or putting stents in or procedures and things like that.

Cancer was always a blackbox because people didn’t understand how best to treat it. That era was a very exciting period where a lot of new scientific discoveries were made and things we didn’t know a couple years ago were presented as facts.

That’s really what attracted me to oncology. I thought there were so many things that we didn’t know about cancer that once we get to know, we’ll be able to develop better treatments for patients.

So it was really an academic and scientific curiosity at the time.

Describe what your typical work day looks like

Everybody does it a little differently. What I do is I see patients two full days a week so I’m in clinic that whole day seeing new patients, follow-up consultation.

The rest of the week I have research projects that I’m supervising, there’s paperwork, administrative work we all have to do, leadership committees that have to do with the cancer center, things like that.

Take us through your days at clinic

Usually the days here start around eight in the morning in terms of having patients check in and start getting lab work done. Then I see them, so I work with a practice nurse who helps me manage the patients and obviously a clinical team that’s involved with taking patients from point A to point B, from coming into the office to going to labs to getting roomed to getting their vitals checked, then eventually getting seen.

So in the average I’ll see about 16 to 18 patients in that given day.

There are different stages so there’s special appointment spots for new patients because obviously those consultations require more time. Then routine follow-ups are about half-an-hour and research patients have their own spots because they need additional procedures.

These are patients enrolled in clinical trials who have specific protocols about how to treat different symptoms or what type of monitoring is required so usually we have designated spots saved for these patients because they need more attention by other people, as well, like personnel. The rest of their experience is the same. The day usually wraps around six in the evening.

Advice on whether patients should get a second opinion?

In general, most oncologists feel comfortable about second opinions.

I think I can see why some people can maybe take it as a slight because the work of the physician-patient relationship, it’s almost like double-dating. They feel like they have a good relationship so they may feel threatened.

We may all do that, I’m not saying others do, but I do think it’s a valuable service for the patients because patients, especially if they’re told that their choices are limited or maybe they hear something they weren’t expecting to hear, I think it helps them understand it better if they hear it from somewhere else so that they feel more comfortable with their choices.

My advice with second opinions is to really try to make it as useful as possible by speaking to somebody who’s considered an expert in the field because oftentimes, and this has happened to me a lot, I consider myself an expert in hematologic malignancies but no way an expert in anything else so I’ll say I’m an expert but in one thing.

It’s happened to me where patients getting a second opinion from an oncologist who specializes in something else or in general oncology rather than the field that I do.

Sometimes they give a different opinion and it creates a lot of conflict because here I am telling them to do Plan A and a different oncologist is telling them to do Plan B. The patient is confused.

I think it would help to seek out the experts in the field. If you have a second opinion, have it with somebody else who’s let’s say at my level so that it’s a more meaningful conversation.

How can patients find those experts?

It’s hard for us sometimes to know who the specialists are in areas that are not our areas. We all know the specialists in our fields. But I think it’s very hard for patients in general to know who the specialists are, who the true experts are in their area.

I find there’s a lot more information out there about what the good restaurants are or what the good cars are, but it’s very hard to penetrate into the medical field and find who the true experts are. It helps to see, for example, people who are members of national organizations who are doing research in specific areas of interest.

People who are part of what we call the NCCN, National Comprehensive Cancer Network. I think those are good starting points. And also asking other doctors. Usually doctors will know who to send patients to, if they get asked.

More: Cancer organizations and nonprofits →

What is the “survival rate” in layman’s terms?

My motto is one day unfortunately we’re all going to die of something. As long as you don’t die because of this disease, then that’s a success. Increasingly that is a common path.

Progress has really been happening at a really fast pace so any kind of survival data or long-term aggregate data that come from our experience from, let’s say the past ten years, and I can safely tell you and not be wrong that ten years from now, all the survival rates are going to be better.

They’re not going to be 100-percent, but they’re all going to be better than they were ten years ago because of so many new treatments that are coming into play.

So really the experience of the patients treated in the 90s and early 2000s, which is what the numbers come from, does not reflect the cured experience of the patients. That’s another reminder that I put out there.

To me, the only reason to compare survival and toxicity is to be able to compare among different treatments and say okay this is a treatment that’s more likely, with the information we have, to get me to where I want to be.

Or this is a treatment that’s less likely with the information that I have to give me a serious toxicity that I worry about. But other than that, I take it with a grain of salt.

Can patients work through cancer treatment?

That’s another big thing people ask about. There’s people who really get a lot of pleasure out of their work and they feel like a normal person because they’re working.

And obviously there’s people, there’s a lot of people who feel work is a little more of a drag when you’re dealing with something as important as that.

So we try to work with what the patients’ desires are. A lot of the treatments that we do actually are compatible with work and a lot of the employers I find can make a lot of adjustments for somebody who wants to stay employed during this treatment – who wants to stay active in work , they’re employed because technically they’re going on disability.

There are treatments where you can work full-time, and there’s treatments where you need to take some time off in the beginning and go part time afterwards. So it varies and it varies also depending on what the patient wants and what their financial situation is of course.

»MORE: Patients talk about working during cancer treatment

Relationship with Patients

What is it like meeting new patients?

A big part of meeting a patient for the first time is reviewing all the records. Usually, the average patient that I see has been through another oncologist already.

A lot of our patients are referrals from other oncologists either for clinical trial or a specialized therapy that can be provided with us. So we have a pretty good communication system in terms of the notes that describe the patient’s course, imaging that’s required, pathology samples that have been reviewed, laboratory work up, and all of that gets reviewed.

If it’s a disease where I feel there’s a gap in my thinking about it, I will have to do some preparation either beforehand or a lot of the times, afterwards, after I meet the patients, in terms of doing some research to see how that would differ from another case of the same kind. But usually I don’t do a lot of work before the clinic day to prepare; it happens in real time. I find it works better for me.

Nowadays, you may make the argument that patient interaction, some people think it’s very typical because you don’t gain a lot of information from it.

I feel I gain a lot of information just by talking to the patient directly.

Maybe it sounds like a cliche. The truth is you get to understand what their life is like, what they can do, what they cannot do, what their expectations are out of the treatments you’re going to be offering.

So that really navigates me through what the best choice for them is, because there can be a lot of choices for any given thing. But every patient is different so I try not to go in with my idea of what I want to do, I want to see what the patient is thinking I want to do or what the patient wants to do and work my through that.

How different are patients?

Some patients have done a lot of research, they’ve talked to a lot of different people, they have a pretty clear idea of what is done. For them, the disease is a given, they understand what they’re dealing with, they’ve dealt with it psychologically already at some point before coming in.

They’re here really for expertise so I tell them what I would do based on what they have, then they compare and contrast that with other physicians and make a decision..

Some people are really here to look for the first advice. They don’t know anything about the disease, they don’t want to look anything up, they don’t want to do any research because they’re scared of what they’re looking at.

They are the patients I enjoy seeing the most because you start from a blank slate. They want to have advice about what to do with basic things in their lives, they want to have advice about the cancer in general, they need a lot more hand-holding than other people.

I tailor my approach to what their needs are. Obviously, there’s some standard things that I provide during the visit but a lot of it also depends on what the patients’ wishes are.

Advice for patients on hitting the right balance (of opinion) with the doctor?

It is a little bit of a dance and everybody obviously experiences treatment in a different way. Our experience as doctors has nothing to do with patients’ experience. One complaint I hear from patients is, “You guys don’t take the drugs you prescribe.” True. We can’t do that.

I think with me, I can see the balance. It works well for the patient to be open about it. There’s also a tendency oftentimes, especially because there’s so much written information out there and so many misconceptions about things that, I think there is a tendency to blame a lot of symptoms on the cancer medicine. Those are the misconceptions we want to break.

A lot of the times there will be important things that the doctor does need to know about. It will lead to dose reductions.

There are some medications that we can change the dosage because we have experience with doing it. There are some medications where we may say I know you’re feeling this way but if you want to get this done, you can’t change it.

I can see why patients would feel hesitant about talking about that with their oncologists but I think it is a good idea to do it.

What are common questions from patients?

A lot of the questions come from patients experience about cancer in general. That may come from either well-wishers who talk to the patients before their visits, may come from the media, may come from movies, may come from looking up things on the web.

Most common one I would say is, “What stage am I? Is this advanced stage?” because people associate that with a worse outcome.

Oftentimes, I’ll hear why did I get this? What did I do in my lifestyle? Genetics or activities that led to this problem? The other that relates to this is can other members of my family get it, especially children. Can my children get this because I got it? Those are the three most common ones that I get asked.

Are there questions patients should be asking?

I think a lot of people get overwhelmed by the toxicity of the treatments that we talk about so they focus on what side effects can I get, how can I get through these side effects.

Rather than thinking about more long-term issues like are all these things manageable, after I’m done with my treatment, how will my life look like, so focusing on more quality of life issues and functionality rather than specific side effects that may happen because of the treatment, I think that gives us a better idea of what to do.

When I say long term, I mean after the treatment’s done. Usually most treatments are self-limited in six months, a lot of oncology treatments happen in six months. So after those six months are done there are long-term side effects which will happen in the first year afterwards.

Then there are longer-term [side effects] which would be for the rest of somebody’s life. I think a lot of patients focus on the six months ahead and maybe sometimes get a little panicky about what’s going to happen during this period of time, which is expected, but they fail to realize that after that’s done, you can go back to having a healthy lifestyle. That’s where I want the focus to be.

Examples would be having a good diet, an appropriate diet for your disease and your treatment, getting physical activity in, doing some mental exercises is what I call them to make sure so-called chemo brain is not such a big deal, and really using the time that you’re going through treatment to buttress yourself up so in the future you can return to a good quality of life.

What are the top hot topics that come up with patients?

Nutrition and physical activity. Obviously both of those are areas that a patient feels they have a lot of control over. They may not have a lot of control over what nature did to them or what we’re trying to do to them but they have a lot of control over that, so there are patients who are very educated about nutritional choices or activity regimes and they want more information at a very high level that oncologists generally are not very good at providing.

We do have special counselors who focus on nutrition and cancer that we refer the patients to. Some patients are even scared about nutrition. They think it’s something in their diet that caused their cancer.

I get that a lot. I eat a lot of meat, could that have been the reason or I’m eating a lot of processed sugars and should I go to a sugar-free diet?

I try to reassure them that yes, maybe that has contributed a little bit but that’s not the reason why this happened and try to work with them to see do they really want to make a change or is this something coming from their family or environment where they’re forced to change their lifestyle to something they’re not happy with just because they have this disease. We usually spend a good amount of time talking about that.

Sexual activity is another thing that often comes up.

These people are scared, they don’t know if they should be having sex, not having sex, can we pass it on with sexual activity? Doctors think that’s kind of unusual question but it’s actually I think a very real question for patients so that’s another thing that comes up.

Also, fertility. Can they have children in the future?

If they’re young and they’re dealing with the cancer, is there a way to preserve that? So there’s a lot of these things that a usual oncology visit will entail.

»MORE: Fertility preservation and cancer treatment

What do you tell patients about engaging in sexual activity?

I always tell patients sexual activity is okay. There is a small risk of fetal malformations or miscarriages from patients receiving chemo so when of course patients are under chemotherapy we explicitly advise them not to have kids so to use protection to avoid that.

But in terms of chemical exposures or in terms of any risks to their partner, there’s none that are identifiable.

We do sometimes, depending on the patient’s interest, break it down to the granular activities that are involved. There are some activities that are higher risk than others in terms of, let’s say someone has a weak immune system, can they get infections from certain acts? So we would go into that but overall as an area of personal well-being, it’s actually pretty supported by oncology.

What do you tell patients about fertility?

In terms of fertility, there are some treatments that we provide especially young people that have a risk of infertility. There are ways to prevent that so in men there’s sperm banking, which can be done in many centers including here.

For women sometimes it’s harder to do depending on where they are in their cycle or in their need for treatment. But there are ways for women to either freeze their eggs or embryos or even ovarian tissue that can be used in the future for new babies.

So there are ways to work around that and that’s usually part of our discussion upfront because that’s the time when that needs to happen. After we start the treatment, the whole point kind of is moot.

Thank you Dr. Babis Andreadis!

Ask A Hematologist

Advances in GVHD Treatments and Clinical Trials

Hematologist-oncologists Dr. Satyajit Kosuri and Dr. Shernan Holtan, patient advocate Meredith Cowden, and LLS clinical trial nurse navigator Ashley Giacobbi discuss the role clinical trials play in advancing the GVHD treatment landscape.

...

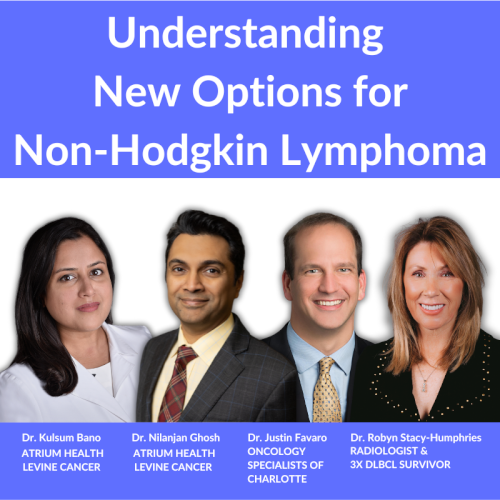

Accessing the Best Care for You or a Loved One: Understanding New Options for Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma

Dr. Kulsum Bano, Dr. Nilanjan Ghosh, and Dr. Justin Favaro discuss the latest advances with 3-time DLBCL survivor and patient advocate Dr. Robyn Stacy-Humphries.

...

Rafael Fonseca, MD

Role: Interim executive director, hematologist-oncologist

Focus: Multiple myeloma, new drug development

Institution: Mayo Clinic

...

Farrukh Awan, MD

Role: Hematologist-oncologist, associate professor

Focus: Leukemias, Lymphomas, BMT

Institution: UT Southwestern

...

Nina Shah, MD

Role: Hematologist-oncologist, researcher

Focus: Multiple Myeloma

Institution: University of California, San Francisco (UCSF)

...