Shelley’s Stage 3B Colon Cancer Story

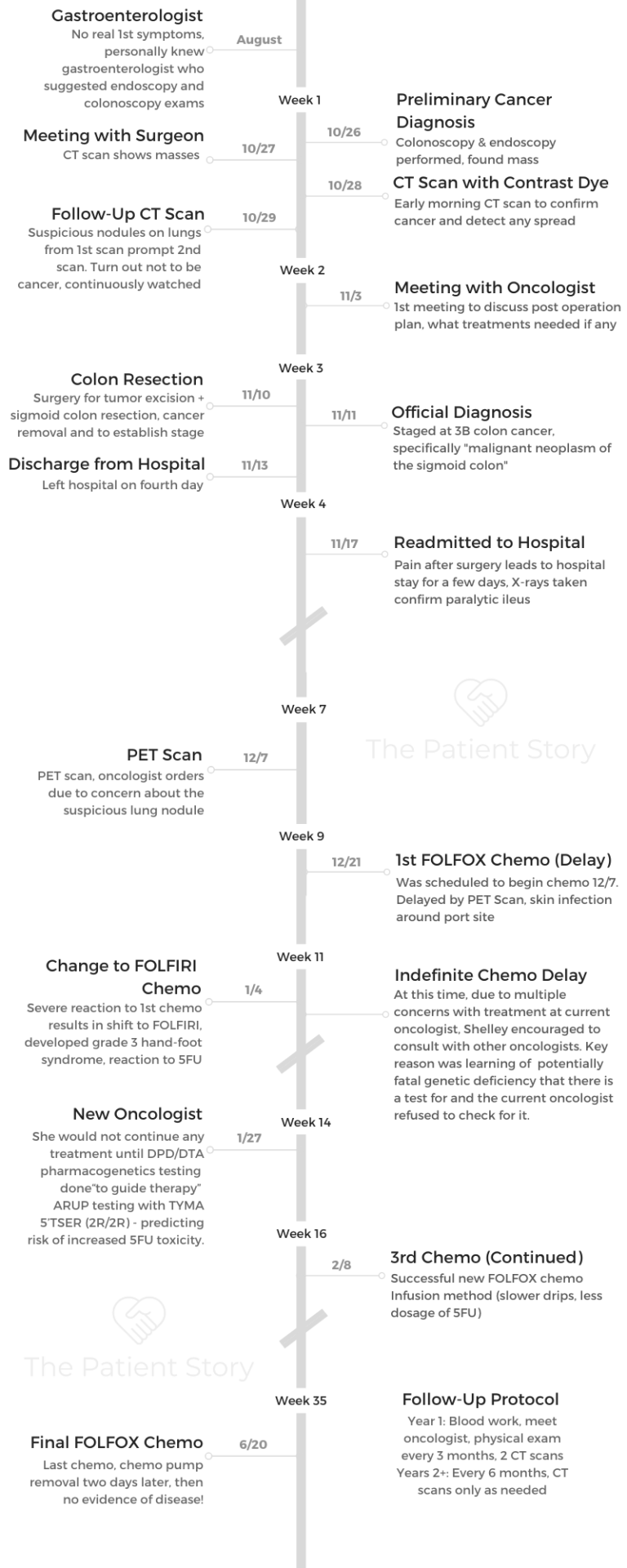

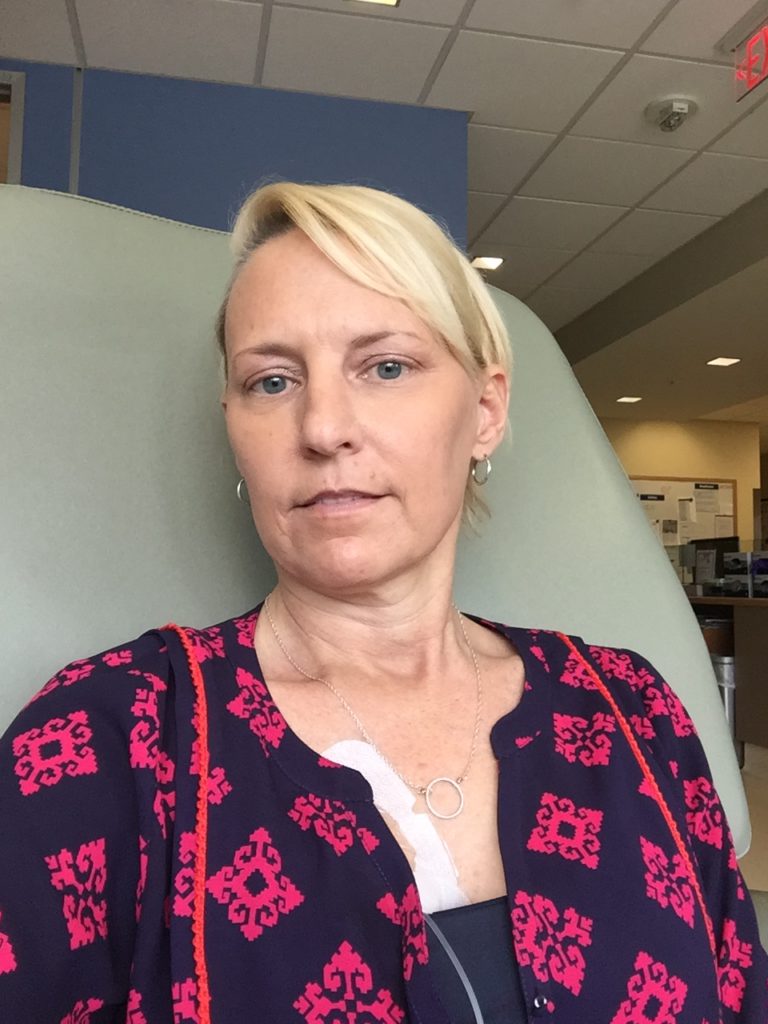

Shelley shares her stage 3B colon cancer story, which began at 49 years old. She details undergoing treatment, her colectomy (surgery), adjuvant chemotherapy, and recovery from it all.

In her in-depth story below (with a full video interview), Shelley also describes the issues that were top of mind for her after her colon cancer diagnosis, including managing through losing her hair, how important it was to advocate for herself as a patient, how she asked for help, what support made the biggest difference, and her transition to survivorship.

- Name: Shelley B.

- Diagnosis: Colon cancer

- Age at DX: 49

- Staging: 3B

- 1st Symptoms:

- No real first symptoms

- Scheduled routine colonoscopy and endoscopy showed mass

- In hindsight, there had been some mucus in stool

- No real first symptoms

- Treatment:

- Surgery

- Colectomy (colon resection)

- Adjuvant chemo

- FOLFOX

- Surgery

- Diagnosis

- How did you know something was wrong?

- Describe the colonoscopy

- What are some of the tricks to hide that colonoscopy prep liquid taste?

- What happened when you woke up from the colonoscopy?

- Your gastroenterologist had already set up all the appointments for you

- Did you break the news to loved ones right away?

- Preparing for Treatment

- Describe the CT scan and contrast dye

- How did the surgeon describe the colon surgery (colectomy)?

- You had a follow-up CT scan because they spotted nodules on your lungs

- The surgery needs to happen before staging of colon cancer

- How did the oncologist describe the overall treatment plan?

- Tip: having other people at your appointments is helpful

- Colectomy (Colon Resection Surgery)

- Adjuvant Chemotherapy

- End of Treatment

- Post-Treatment Reflections

- It's important to be your own advocate as a patient

- When did you feel you needed to self-advocate the most?

- It was important to you to research your own cancer and case

- How did you ask for support during treatment?

- Guidance on giving support to cancer patients and families

- How has it been with survivorship?

This interview has been edited for clarity. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider for treatment decisions.

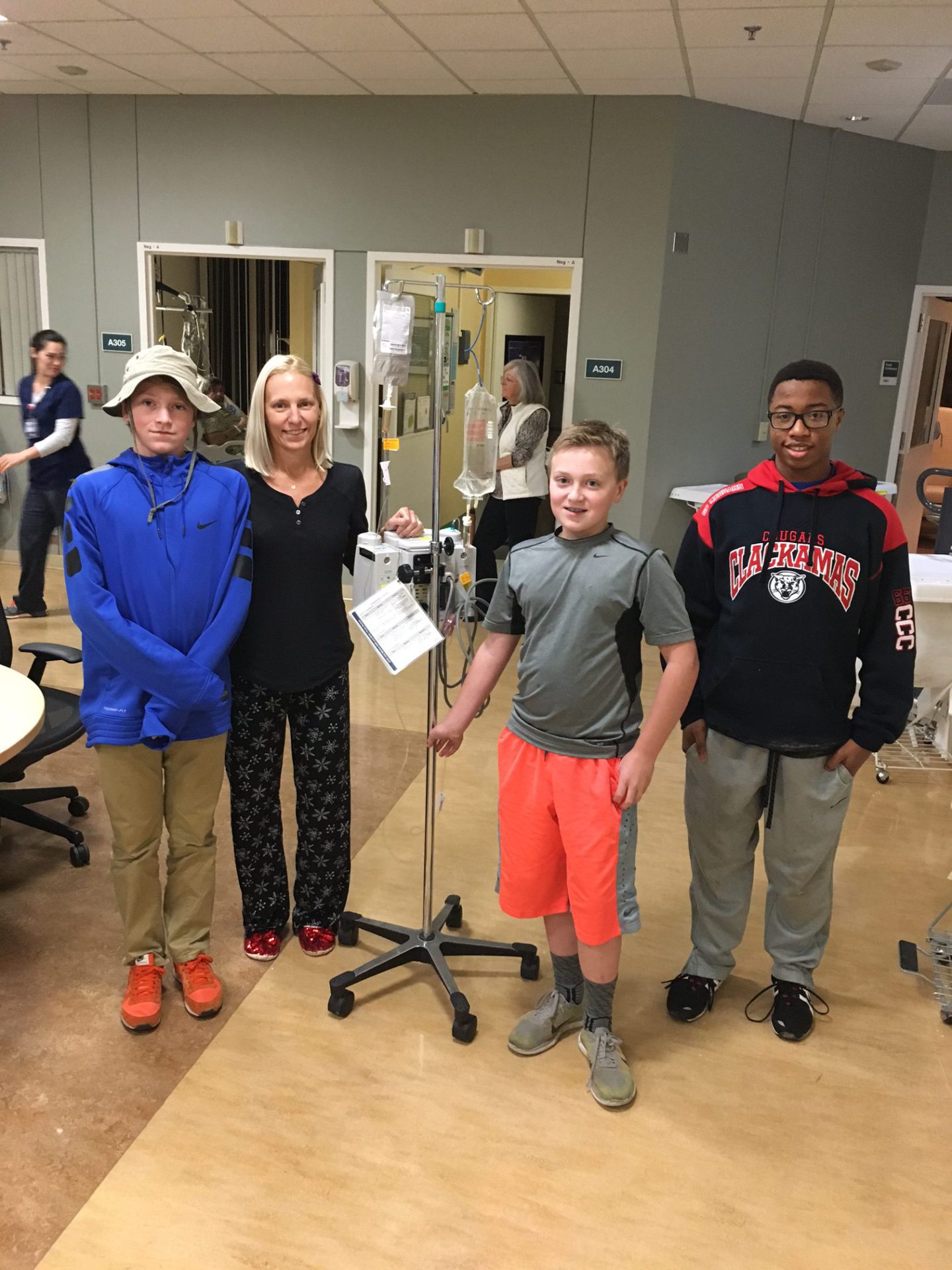

The love and how many people we were and are blessed with in our lives — you hear about it, but you really see it when it happens to you.

When you go through some sort of crisis like that, you really realize the people who care and the people who are there and step up.

I just felt like the more love that I have with me, the stronger I could get through it.

Shelley B.

Diagnosis

How did you know something was wrong?

I really didn’t know something wasn’t right. I have a wonderful gastroenterologist who’s in our community. Our kids go to school together, so I knew her somewhat personally.

I have had reflux since my second child was born. I take prescription medication for that, and another doctor said, “You haven’t had an endoscopy in 6 years. You should have one.” So I put it on the radar.

I kept putting it off but finally scheduled it. When you have a colonoscopy you usually meet with the doctor several weeks before for prep. She said, “Since you’re having an endoscopy, why don’t you get a colonoscopy at the same time since you’ll be turning 50 next year.”

I hadn’t even thought about that yet, so I just said okay. That was late summer. Then I finally scheduled the endoscopy and colonoscopy for end of September, but I delayed them for some scheduling reasons.

In early October, I had a pretty significant virus and had medication with some pretty serious side effects. One of them is listed as rectal bleeding. That month, I had a little bit of rectal bleeding. I let my gastroenterologist and primary doctor know.

She decided to just get me in earlier for my appointment. That’s how I went in. She didn’t expect to find anything. I didn’t.

I had a little bit of mucus in my stool off and on through that last year before that, but I didn’t think anything of it other than dietary changes. I didn’t have stomach pain or a lot of symptoms we’re told to look for.

Describe the colonoscopy

I’m a big advocate for the colonoscopy, so I’ll push anyone who mentions they’re putting it off. The colonoscopy is no problem. You basically take a nap! It’s great.

The prep is the worst part, which people build up. It’s really not that bad. There are many preps now, too. If you like to eat, you can’t eat for a day and a half. That’s maybe a part of that, but you can have popsicles and jello, candy, things that will pass right through.

The prep is just a lot of liquid that doesn’t taste great, but there are all kinds of tricks I’ve learned to mask the taste or hide it.

What are some of the tricks to hide that colonoscopy prep liquid taste?

Getting the liquid into the back of your throat rather than trying to taste it. Sucking on a menthol or some candy that has a strong aftertaste before the prep.

You’re supposed to drink a fair amount each time over those 24 hours. At some times, you drink 8 to 16 ounces all at once or every thirty minutes, depending where you are on that day-and-a-half prep. Having something strong-tasting in your mouth before and immediately popping it in after can work.

Holding a dryer sheet over your nose so that you don’t smell it.

I don’t know that it’s the taste as much as it’s the smell when it’s going down. Those are a few off the top of my head.

What happened when you woke up from the colonoscopy?

In clinics, a lot of them are outpatient, so the recovery area is usually a row of beds with curtains, especially with day procedures. I didn’t go into the same area I came out of. They put me down in the one at the end of the hall.

I was just waking up from anesthesia, so I was a little loopy. I joked with my husband that this was the one they brought you to for bad news. I didn’t know, but I was accurate. My doctor later told me that was true.

We waited for her. She came out with red eyes and tears in her eyes. She sat down and said, ‘Shelley, you have cancer.’

The first thing I did was laugh. That wasn’t even on anybody’s radar. I had family members with colitis or Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS). The worst we thought was they found a manageable stomach condition or GI condition.

I was in shock. My husband started crying, and then I apologized to her for having to tell me, because I couldn’t imagine being in her shoes. Then I think it started to sink in. I knew what she was saying, but I was so stunned.

Your gastroenterologist had already set up all the appointments for you

Bless her, she’d already been on the phone with the surgeon. This was 6 o’clock on a Monday night, and I had an appointment with the surgeon set up by her the next day at 1 in the afternoon.

She also had me get blood work that night at the hospital across the street, and she had me set up for a CT scan at 7 the next morning.

She had all that done before she even came to tell me. It was an utter shock. We didn’t go in with a lot of symptoms where we thought (this would be cancer).

Did you break the news to loved ones right away?

We took that time that evening. We had a family friend home with our kids because it was a school night. She’s like a godmother to me, who lives in the same city. First, my husband called her and asked her to stay.

I was at the point where I couldn’t call anybody because I couldn’t say the words. I was not able to say, ‘She found cancer.’

My husband called my parents, and maybe I was on speaker phone, but they live in Hawaii for half the year. My mom said, “No you don’t.” They didn’t believe it. They thought it was wrong. They thought there was no way the doctor could tell from the colonoscopy. It couldn’t be right. They went immediately into this denial of, “This can’t be happening to our daughter.”

I don’t remember from that how much explaining we had to do to them. But it sunk in pretty fast, and they were amazing. Next, my husband called one of my best friends and told her, then asked her to call a few of my close friends, who could then share it with our other circles. Then my husband called his parents.

We got something to eat while we were waiting for the blood work, and that’s all I remember from that night. We probably got home around 7:30 or so, but I don’t remember where it went from there.

»MORE: Breaking the news of a diagnosis to loved ones

Preparing for Treatment

Describe the CT scan and contrast dye

The next morning, the first thing was the CT scan. I don’t know if I had ever had one, but I certainly hadn’t gone in by myself to the hospital. My husband was at home getting the kids off to school. I went in by myself in this surreal world, thinking, “What is happening?”

I had CT with contrast. I was sitting in this waiting room at the hospital in the radiology area, drinking this contrast, and just terrified, feeling numb. I let time pass.

The CT scan itself was strange at first, especially with contrast, because you lie down like you’re getting an MRI or X-ray. You get slid into a machine, not quite so tight as an MRI, but then they put an IV in so they can add additional contrast during your procedure.

It’s a bit of a strange feeling because when they open up that line, it gets into your bloodstream. You feel this rush of warmth go through your entire body, so it’s a little strange. Not scary, just strange. It also feels like you’re going to urinate, but you don’t.

The scan is not too long. I’m sure I was anxious for the results, but I knew I had cancer already. I didn’t understand at the time, because a lot of times you hear stories for people where it’s the imaging that confirms that there’s cancer.

But for me, the imaging was going to confirm other things, from validating what my doctor had seen to the size and everything else.

Things were happening so fast, so it wasn’t like sitting by the phone, waiting for the results in a panic, because there were so many other things happening.

How did the surgeon describe the colon surgery (colectomy)?

My husband and I met with the surgeon that day at 1 in the afternoon. He does a lot of this work and is very respected in this area. He and his partners do a lot of surgeries in this area.

He explained to us that he’d be going in and would be removing the tumor. I would be getting a colectomy, where they take out a certain section of the colon. It’s the amount they need to take out to get clear margins and can also ideally stitch back together.

They don’t know until they go in, and they prepare you for other things. Whether you’ll need an ostomy bag, you just don’t know. My surgery was in the sigmoid colon but also was very low on that left side, which then comes close to being in your rectum. I did not have rectal cancer, but you don’t know a lot of that (at the time).

They explained they would be looking for margins and taking out lymph nodes to test. He wanted to get the surgery done soon.

They thought they caught it early. Everyone thought they caught it early, but at the same time, they somehow seemed to know it was aggressive even before the pathology. He wanted to do the surgery the next week.

You had a follow-up CT scan because they spotted nodules on your lungs

They’d seen nodules in the CT scan that were concerning enough that they wanted to get a better look at that area. The nodules were and still are an issue that they’re watching, but have never gone in to biopsy. They show up.

That was funny because that was the CT scan where I remember waiting and waiting, feeling like forever. I spent a day. I had just found out I had colon cancer. Then she called with the results that they were just nodules on the lungs and that they were fine.

I remember jumping up and down in the kitchen, then pausing and laughing, thinking, “I’ve just gone from finding out I have colon cancer to jumping up in happiness that it also hasn’t spread to my lungs, all in 2 days.”

There was a moment of humor that I was celebrating this thing where 2 or 3 days before, I didn’t even know I had anything wrong.

The surgery needs to happen before staging of colon cancer

They need the tumor, what the tumor looks like, and the areas of your colon and system the cancer has invaded. Is it just the outer wall of the colon or into another area? Are there lymph nodes involved? How large are those lymph nodes?

They want to take out as many lymph nodes as they can. Then they look for cancer in those lymph nodes to see how many of the ones they took are positive. All of those things go into staging.

How did the oncologist describe the overall treatment plan?

It was pretty casual but straightforward. He, again, said it was doubtful that I was going to need chemo. Everyone thought they caught it early, maybe because I didn’t have a lot of symptoms. I was under 50 years old. There were all kinds of reasons.

He didn’t go into extensive detail. By this time, my mom had arrived in town, and my dad arrived shortly after. She was at all the appointments with me and asking a lot of questions also.

The oncologist described what we kind of knew, the recovery time from the surgery, his estimate of when I would see him again after recovery, and then any decisions about treatment would be made.

We talked about what kind of treatment and how long for what stage, but just a general overview, not a ton of detail, unless they were questions we asked.

He did talk about what they call adjuvant chemo, where you often get chemo when they think they’ve gotten everything, but they don’t know because it maybe has gone into your bloodstream and is outside of the original site, not contained in the colon.

The chemo for that is trying to get any cells that might be in your body to find a place to land. That’s the reason they really push chemo.

That’s a lot of what he explained, because not everyone gets or chooses chemo. Again, a lot of it depends on the stage.

Tip: having other people at your appointments is helpful

As much as possible, it’s critical to have someone at every appointment.

We would all walk in with our notebooks. As a patient, you’re going to be asking questions, but you’re also going through the emotion. It’s you.

The person who’s with you, whether a spouse or parent or friend or any kind of caregiver, they’re having emotions, too. They’re going to hear different things or maybe think to ask different questions.

It would be my mom, my dad, my husband, and I all sitting there with notepads. My mom would take the notepads and actually write everything out based on what everyone had asked or heard. That was really helpful.

Colectomy (Colon Resection Surgery)

What was on your mind pre-surgery (emotional)?

Going in as positive as possible. The night before the surgery, I was journaling, writing about what was happening, listening to one of my lifelong favorite musicians. I was visualizing that I would be healthy. I would pick words along the way to recite.

The day of the surgery, my husband and I had music playing in the room while we were waiting for the operation. We already had a lot of support — cards, help, gifts, things like that.

When I went into the operating room, I visualized everyone in there with me, dozens and dozens of people. It was important to me to engage with the staff in the operating room, whether it be a joke or just “hello,” “thank you,” anything for my comfort, but also to humanize the whole situation.

Why did this evoke such an emotional response from you?

The love and how many people we were and are blessed with in our lives. You hear about it, but you really see it when it happens to you. When you go through some sort of crisis like that, you really realize the people who care and the people who are there, who step up.

I just felt like the more love that I have with me, the stronger I could get through it.

What were the positive affirmations you recited?

“I will be healthy. I will heal. I will thrive. I will survive.”

I would change it up some, but I would say that pretty much daily or some version.

Describe the surgery and recovery

The surgery went pretty smoothly. It was a few hours. It was long, but not some things you hear about. Apparently, which is not usual for me, it took a long time to wake me. That has to do with the anesthesia they give you and how long they estimate the surgery. It took a long time for me to awake.

The surgery was on the 10th, and I was originally discharged the 13th, which was pretty quick. I unfortunately had to be re-hospitalized the 17th through the 20th related to the resection of the colon and what they call ileus.

Partly due to the anesthesia, partly due to them reconnecting the colon and the medications I was on, nothing was processing through my body. I was in a lot of pain, and my colon was expanding everywhere.

How did you learn the staging?

I was blessed that our neighbor at the time, who we were friendly with, turned out to be the head pathologist for that system and put himself on that case.

He was in the operating room, so before I had even woken up. He had brought in an initial report, which normally we wouldn’t get for several days. Then he came and saw me. It might’ve been when he came in and saw me that we knew — the afternoon of my surgery — how bad it was.

The official staging from the surgeon and the final report was a day or 2 after surgery, but the report we got through our neighbor connection was right after surgery.

He came in and asked if I wanted the update. He gave us pictures of the tumor. You don’t think about what it is, but it’s ugly! It gave a very vivid picture of what was really not right.

How did you process the stage 3B news?

When we found out the staging, I knew way more than my whole family. I was crushed. I knew what it all meant. I won’t say we were arguing, but no one else knew what that all really meant but me.

I knew that would mean a recommended minimum 6 months of chemo. I knew it was outside my colon and the tumor itself had invaded the outer colon walls. Not entirely. I knew the size of the lymph nodes was not good.

I wasn’t stage 4, thank goodness, but I knew it was about as serious as it could be without it being stage 4. I was terrified and a little angry at everyone for telling me that we had gotten the cancer early. I felt misled, so I had all kinds of emotions going on.

That’s the moment where I felt like my world was crushed. I’m not sorry I had that knowledge because I could begin to deal with it and process it. It was one blow instead of multiple, continued blows.

Adjuvant Chemotherapy

Describe the port experience

We ended up using the port, [but I had an infection]. I’ve just figured out what I’m allergic to that has caused a lot of the type of struggles I had.

The port infection was not the line itself. It was external. My whole skin, they couldn’t access it because it was too infected.

I’m allergic to 2 different ingredients used in a lot of adhesives, medical tape, dermabond (surgical skin glue), sutures, a lot of glues and things used in medical bandaging and prep clean.

Port infections are uncommon. The port itself, I’m so thankful for having. Other than it being bionic and futuristic, it really worked well.

Describe the FOLFOX chemo regimen

For my case, stage 3 colon cancer, they recommended (at the time) 6 months of chemo. I would go every other week, go in and spend 5 or 6 hours, get pre-meds, and then get the chemo agents.

Then they would hook up a line where I would carry a fanny-pack type bag I’d wear for the next 48 hours at home (a pump), 24 hours a day. If it was a Monday, then I’d go back in Wednesday for them to remove the take-home therapy pump.

I’d be home for a week and a half and do what I felt like I could do, fighting side effects.

What helped you during the chemo infusions?

As far as the chemo days, what helped me was having a specific chemo bag. I didn’t want to see the chemo bag after all that time, but the chemo bag I kept with snacks, a blanket, extra chargers, headphones, things to help me.

The comforts of home, comforts for you. I was given a teddy bear after my surgery. Things that made it more comfortable and made the day pass.

Tips on dealing with the take-home pump

The pumps may be better now, but you have to wear it with a wardrobe change that people don’t talk about with the port. You have to get new undergarments because of where the port is.

That’s something you’ll learn and they may tell you. You have to wear clothes that are accessible for the port. I would get new undergarments with underwires much farther out so they could access the port, and also so it wouldn’t hurt. I also had a lot of camisole and tank tops, as well as button-downs, which wasn’t something I normally wore.

All of those things help with them accessing the port. It helped with the chemo bag and pump because I could wear it over the tank top and have the button-up shirt or a big sweater.

It wasn’t so much that I was trying to hide it, but I was avoiding the chemo lines. It tucked those lines into the tank or camisole and made it more comfortable, not so much about hiding it.

I ended up with different pants, too, because colon cancer involves a major surgery, and it takes a while to heal. A lot of times where the scars are is where the natural pant line would be.

I ended up with things with elastic waists, where I could adjust the height of the pants. That’s something people can do before treatment begins, too. It helps pass those days and weeks before the treatment begins. It can make life a lot more comfortable.

Sleeping is an adjustment. A body pillow helps or a lot of pillows, because depending on how you sleep, you may have to change how you sleep. I got used to the sound of the pump, but earplugs help, too.

What were the FOLFOX chemo side effects?

I was on FOLFOX, though I also had one cycle of FOLFIRI. FOLFOX is the recommended chemo for my stage.

They pre-medicated me for nausea. I still got nausea, so there were other medications I would take home that are pretty common for people with nausea. I’m prone to nausea.

Different people are prone to different side effects. Some people don’t have a lot of side effects. A lot of what side effects someone gets and how strong they are depends on the makeup of our body, our immune system, things like that.

I tended to react pretty severely to a lot of the FOLFOX. I had the nausea, fatigue, a lot of skin rashes. Some tied to the chemo agents, and some not. They give you a list of the expected side effects. I had the majority of them to different degrees.

I think the 2 hardest side effects in that — small-world problems — included not being able to drink anything cold, liquid-wise. I love Diet Coke. I am not a coffee drinker. I still struggle with water, because I loved it. But having to change that to warmer and room temperature, I don’t love water as much.

Anything cold when you are on FOLFOX, you start feeling like you can’t breathe. You can, but you’d get cold zaps. I don’t know how to describe them, like mini-lightning feelings through your fingers, especially if you pick up a cold glass or open a cold car door. Trying to pick up an ice cube? Forget that.

That would be another thing. I got these white cotton gloves. If I was trying to do things in the kitchen, I could use those gloves and then throw them away. Those were the strangest things: the intolerance to cold liquid and even cold air.

If you’re in a cold-air climate, you’ll have to have a scarf over your head and breathe into that because breathing in that cold air has that same sensation.

»MORE: Cancer patients share their treatment side effects

Describe the hair loss

That was a big one for me. With a few exceptions of the Dorothy Hamill when I was younger, I’ve always had shoulder to long hair.

It’s not so much vanity, like people might think. It’s part of your sense of self. It’s walking by, looking at the mirror, and adds to the whole out-of-body experience.

I got a lot of steroids, and they wanted me to put on weight before the treatment. Then I kept gaining weight. I got to where I didn’t look like myself. Then you add the hair loss.

The hair was just a part of my identity. I don’t think I look good with short hair, personally. With the treatment I had overall, most people get their hair thinned. You may or may not have to cut it.

I lost enough hair that at first I cut it shorter. Then it got to the point where I didn’t want to be obsessing about it every day, worrying about it.

I didn’t want cancer to take my hair, so I decided to cut my hair.

I had pretty thin hair, so my stylist cut it for me. Then I had some dear friends go wig shopping with me. Our community donated money to buy me a wig, which was mind-blowing because not everyone understands how much that could mean.

»MORE: Dealing with hair loss during cancer treatment

I had a long-hair wig. We ski a lot, so I’d just wear a hat with the wig. It never really looked normal with the wig. That helped me feel more like myself. Everyone said, “Your hair looks cute short,” but I didn’t feel that way. Any time I see a picture of me with my hair short, I think of cancer.

This happened to me with no genetic history of my family. Because I was under 50, they did all those tests. I didn’t meet any of the criteria of people they say might get it: male, eating red meat. I’m female and vegetarian.

I didn’t have any of the underlying risk factors. It just happened. Life happens.

I felt, early on, if anything is going to come out of this, it has to be that I shared my story so it doesn’t happen to anybody else. I was very open, but at the same time, I hated going out and being the “cancer girl.”

It was hard to feel like I looked like I had cancer, even though everyone was really kind about it.

End of Treatment

How did treatment end after chemo?

They usually do a scan towards the end of the chemo regimen.

At that point, I had scans every 6 months, so the first would have been in October. I had a scan around March. I had chronic problems with my GI area ever since the colon resection surgery.

They do a marker toward the end of treatment, doing a scan. They drew my blood work, cancer markers, CEA levels for colon cancer. I think no signs of cancer are anything below 2.5.

Mine was, even with stage 3 cancer at the beginning, 2.6, so I never really relied on that, but they did draw that every week during treatment. They did do CT scans, the CEA levels, and then they scheduled me for a colonoscopy.

What has been the follow-up protocol?

The first year, every 3 months I’d meet with my oncologist and do blood work, as well as a physical exam. The CT scans were twice a year for that first year.

It gradually decreases. At 2 years, I met with her every 6 months and got the blood work done. For colon cancer, most recurrences happen in the 2 to 3.5 years.

They kept me at 6 months. I just got to the 4 year. That pushed me out to see my oncologist every 6 months, but the CT scan is as needed.

The CT scan I put a lot into, but I don’t put a lot into the blood work because that wasn’t a big factor for my case personally. I don’t put a lot into percentages, because I didn’t have a high-percentage chance of getting this cancer in the first place.

Post-Treatment Reflections

It’s important to be your own advocate as a patient

What is critical is self-advocacy. There are too many stories I know where things could have gone differently had people felt they could advocate for themselves.

It is hard. It’s hard to stand up to someone in the medical community and in a position of power, but I kept in mind that they’re human. They make mistakes, and they are working for you in a way.

You have to do the amount of learning that you can tolerate without it hurting you in a negative way. The self-advocacy, whether it’s you or a caregiver, there’s got to be someone in any way possible pushing the envelope for answers. I think that’s critical.

To put it simply, in the case of a family friend’s mom who’s no longer with us, self-advocacy could have saved her life. In my case, a lot of things saved my life. My surgeon, doing the colonoscopy. A lot of people saved my life.

But I also feel that self-advocacy likely saved my life.

When did you feel you needed to self-advocate the most?

Self-advocacy isn’t easy for a lot of us. It’s especially hard when you’re going through something traumatic, but it’s so important. Trying to be brief, after my first chemo, I had some really horrible side effects and was in and out of the emergency room. They were trying to figure out what I was reacting to.

They didn’t necessarily know which chemo agent. It’s hard to know, but it was all documented. When I went in for my second chemo, my oncologist had been out of town for much of that time around the holidays.

By the grace of the universe, a friend of ours sent me this article about this rare genetic deficiency that can be fatal in cancer patients.

It’s DPD (dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase) deficiency. It’s not common. There’s 5% of people who have it, but there is a test for it. It’s an expensive test, and my oncologist wouldn’t do the test. We had suspicions that maybe that might be the case with me because of the symptoms. I had that severe reaction after the first chemo.

They wouldn’t do it. They did the second chemo, which has one of the same agents, the one that the 5% have a genetic inability to process. As a result, the chemo they switched me to isn’t known to be effective for stage 3 cancer. I had read a lot about that.

After that second chemo, it was concerning because they were recommending I do a chemo with no real evidence of being effective for stage 3. Then I developed a severe case of HFS (hand-foot syndrome). It’s basically severe burning of your hands and feet, where you lose layers of skin.

Mine ended up being grade three, which is really high. It became obvious that they wouldn’t test me for it. The chemo they switched to me, which wasn’t supposed to be effective, concerned me because I didn’t understand why they were putting me on that and weren’t testing me for the deficiency, yet it was coming together that I seemed to have all of these symptoms.

The long and short of it is I was encouraged or pushed a little to look for another oncologist, which terrified me.

I had already had delays in treatment. I thought, “Well, if I can’t trust this doctor, who can I trust?” My mom, bless her, did a lot of research. This same name kept coming back to us, which was the universe maybe saying, “Here you go.”

We did a consult with this oncologist at the end of January. My second chemo was January 4th. They couldn’t do chemo because of how severe the reaction was.

She’s the one who looked at me and said, “That’s the worst reaction I’ve ever seen.” She wouldn’t do any chemo without the genetic testing. She did that among other tests, and it turned out that I had the gene.

They had to lower the 5FU in FOLFOX, which is in both of those chemo regimens. My body could only process a fraction of the 5FU. They had to watch it to see how my body would react all the way through.

Had I listened to the oncologist I was going to, I don’t know what would have happened, because they were wanting to treat me with this chemo that was poisoning me and with no known evidence that it was effective for stage 3 cancer.

I don’t want to think about it, but when I had a moment of strength after everything was said and done, I wrote to them and told them very calmly and without anger where I thought their practice needed to be looking and that people were human.

Essentially, the point is, my chemo was delayed — knock on wood — but it doesn’t seem to have affected the long-term outcome. I went through a lot of physical suffering. A lot.

Had we not learned about this test and this condition — here comes the research part — and had we not self-advocated to switch oncologists in the middle of chemo, I don’t know that I’d be sitting here today.

I know that’s a large example of self-advocacy. There are so many examples that are smaller, but I can’t say enough about speaking up for what you need and what you need to know. You should be able to understand your treatment, why they’re doing it, and why they chose that.

»MORE: How to be a self-advocate as a patient

It was important to you to research your own cancer and case

I’m an avid wannabe medical researcher or any researcher. I research a lot. In regards to my cancer, as a note, I do think it’s important for people to learn as much as they can.

Not everyone is a researcher, and people have to consider how it impacts them.

For me, the more I knew, it didn’t make it worse for me. In a way, it gave me more power because then I wasn’t shocked and was able to separate all those things I learned. I wasn’t just reading mainstream medical things. I would read major studies done by hospitals and all of the cancer medical sites.

I would read and subscribe to medical journals that you’d have to have access to. I truly mean it’s important to know enough, because that’s the way you have to advocate.

How did you ask for support during treatment?

It’s hard, like many of these things, for us to ask for support. My husband and I both fought it. Our friends wanted to set up a meal train and help with kids, and I really fought it.

Then someone said to me, “There’s a culture where it’s an insult to not accept help.” In most cases, people want to help. It’s not that we have to go out and say, “Please help me.” We maybe do in a specific situation, but it’s hard to ask for help.

What I’ve learned in that situation, for myself and in helping other people since then, is when you accept help, you’re giving a gift to other people. They wouldn’t be offering it if they didn’t want to.

It helps you more than you even think it will at the time. When you’re just starting out, you don’t necessarily think you’re going to need help because you don’t know how you’re going to feel.

If you feel great, you can cancel or postpone it, and people will understand. The biggest thing is allowing them to help. We had so many blessings of that.

Guidance on giving support to cancer patients and families

The other thing I’ll say for people who want to help. The people who need help don’t always know what they need. They don’t want to ask for it. I’m guilty of it, because it’s hard to think of things.

What I learned from that experience is if you don’t know how to help or if you say you want to help and they don’t know what they need, just do something.

Examples are bring bagels and cream cheese, because for them or for their kids, it can be snacks or meals. We had friends show up and put up our holiday lights. You say, “I don’t know if I’m hungry,” and they’d say, “I’m bringing a burger, so which one do you want?”

The times that I didn’t know what I needed — and I don’t mean to always say someone should feel forced to do something — but even visits, sometimes you don’t want them. The worst thing that happens is someone comes, and they just drop something off or yell up the stairs, “Hello, I love you!”

There were times I thought I didn’t want to see anybody, telling my husband to tell them to go away. She didn’t. She came and sat on my bed. We had the best conversation about nothing.

The importance is to accept it and think that maybe you don’t need it, but you can give them the gift (of helping). If you’re the person wanting to help and you don’t know what to do, do something simple. It could be sending a card or sending texts.

Something that meant so much to me was people would send texts with positive quotes, or they’d give me these little bracelets or necklaces or rocks with symbolic worlds.

»MORE: What kind of support cancer patients say helped the most

How has it been with survivorship?

I think it’s important for other people to know that it looks different for everyone. We imagine we’re going to be doing great and work out through treatment, or we’re going to continue working through treatment, all these things where we have some idea.

I’m going to be done with treatment. I’m going to run a marathon. Maybe someone is, but be forgiving and loving of yourself and knowing that you are a survivor the minute you start treatment or even diagnosis. You’re a survivor. That’s a wonderful thing to celebrate.

But when treatment ends, life doesn’t magically go back to normal. I was told by a doctor that I have beyond the utmost respect for that I probably wouldn’t feel like I could do everything I wanted to do for 3 years.

I looked at him, but he knows me well enough over time. I didn’t get mad. I knew what he meant. He meant, “Maybe you’re a marathon runner. Maybe you run a marathon, but you don’t run it to the standards you think you might or had before for those 3 years.”

It’s a general marker, but there are things that will feel better sooner and things that will linger. It doesn’t mean you feel horrible for 3 years, but maybe you don’t hike as fast or you don’t jump out of bed.

I had occupational therapy, and my memory recall is better now, but the first year and a half, trying to remember a word, I’d be like, “Don’t tell me!”

Those things just take time. It’s hard to accept. It’s a bit hard with the outer world because you start looking better, people think you’re better. In a lot of ways, you’re still recovering, and you’re still maybe suffering, depending on different side effects and cases.

There is a challenge with the community. Unless it’s the closest friends you tell and are brutally honest with, there’s not really an understanding. There’s more and more in the medical field, but even in the medical field, the long-term effects are still new.

There are a few things that might never go away, but not everything stays rough, and not everything goes away immediately. Just know that it does get better.

Inspired by Shelley's story?

Share your story, too!

Colon Cancer Stories

Kasey S., Colon Cancer, Stage 4

Symptoms: Extreme abdominal cramping, mucus in stool, rectal bleeding, black stool, fatigue, weight fluctuations, skin issues (guttate psoriasis)

Treatments: Surgeries (colectomy & salpingectomy), chemotherapy

Chloe W., Colon Cancer, Stage 3

Symptoms: Severe abdominal bloating, weight loss, lack of appetite, fatigue, vomiting, high ketone levels in urine

Treatments: Surgery, chemotherapy

Kristin T., Colon Cancer, Stage 2

Symptoms: Chronic digestive issues, bloating, abdominal pain, unpredictable bowel habits, unexplained weight gain, nausea, fever

Treatments: Surgery (removal of the tumor, right ovary, right fallopian tube, and part of the small intestine), chemotherapy

Mark S., Colon Cancer, Stage 3B

Symptom: Intermittent cramping of varying intensity, localized on the right side

Treatments: Surgery (colon resection), chemotherapy

Shannin D., Colon Cancer, Stage 4

Symptoms: Severe pain where tumor blocked colon, vomiting after eating, weight loss

Treatments: Chemotherapy, immunotherapy, surgery