Directing My Life with Polycythemia Vera: Filmmaker Todd Strauss-Schulson’s 17-Year Story

Polycythemia vera (PV) changed everything for film director Todd Strauss-Schulson when he received his diagnosis at just 28 years old. This rare blood cancer, affecting fewer than 200,000 Americans, didn’t stop Todd from building a successful directing career or living life to the fullest. His 17 years of experience with polycythemia vera offers hope, practical insights, and inspiration for anyone navigating life with this myeloproliferative neoplasm. Todd’s experience is an example of how managing symptoms with regular phlebotomies and building a strong relationship with your care team means a PV diagnosis doesn’t have to define your future.

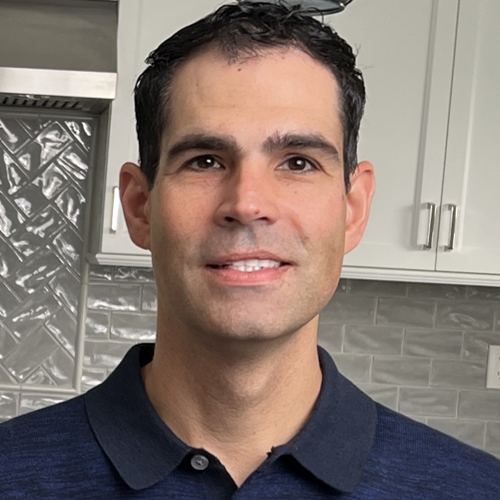

Interviewed by: Taylor Scheib

Edited by: Chris Sanchez

Todd’s health awareness started early, shaped by witnessing his father’s health challenges. A routine physical in L.A. flagged abnormally high blood counts, setting Todd on a path filled with uncertainty. A bone marrow biopsy confirmed PV and the presence of a JAK2 mutation or Janus kinase 2 mutation (a gene mutation found in about 95% of PV patients that provides instructions for creating a protein that promotes the growth and division of cells). These terms were initially foreign, but soon became part of his reality.

Navigating polycythemia vera wasn’t easy. Todd faced anxiety, fear, and countless questions. But a pivotal encounter with his doctor, Dr. John Mascarenhas at The Tisch Cancer Center at Mount Sinai in New York, transformed his outlook. Dr. Mascarenhas didn’t just provide medical care; he offered reassurance: “I got you.” This phrase became a comforting anchor and set the scene for the establishment of a strong doctor-patient relationship.

Living with PV for 17 years, Todd manages his condition with regular phlebotomies or blood extractions, aspirin, a health-conscious lifestyle, and working closely with his care team to track his symptoms. Yet, it’s not just about treatments. Todd openly discusses the invisible anxiety that lingers, how something as simple as a bruise can trigger worry, and how humor-filled texts with his doctor ease his mind.

What stands out is Todd’s proactive approach. He doesn’t let PV define him. He embraces life passionately, advocates for himself, and shares his story to inspire others.

Read the story and watch Todd’s video to uncover more about his experience, including:

- His unexpected diagnosis at 28 that changed everything. Find out how he copes.

- What living with polycythemia vera really looks like — Todd shares it all.

- From anxiety to advocacy: his emotional PV transformation.

- How Todd leverages his creativity and experience to manage his rare blood condition.

- How he transforms life’s challenges with PV into empowering lessons.

- Name:

- Todd S.

- Age at Diagnosis:

- 28

- Diagnosis:

- Polycythemia Vera

- Symptoms:

- None: discovered during a routine physical that uncovered extremely high blood counts

- Treatments:

- Phlebotomy

- Aspirin

Thank you to Incyte for supporting our patient education program. The Patient Story retains full editorial control over all content.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider for treatment decisions.

- About Me

- How I Found Out I Had Polycythemia Vera (PV)

- Putting My PV Diagnosis in Perspective

- Managing My Disease — and Anxiety — for 17 Years

- My Father’s Diagnosis Helped Me Navigate My Own

- Tracking My Symptoms and Integrating PV Into My Life

- Building a Relationship With My Care Team

- I’m Living My Life

- Why I Share My Story

- My Advice for Those with PV or Another MPN

I am not PV. I have it.

It’s part of me. It’s not the whole me.

About Me

Hi, I’m Todd. I’m a film director and writer, and I live between New York and Los Angeles. I was diagnosed with a rare blood cancer, polycythemia vera (PV), in 2008, when I was 28 years old.

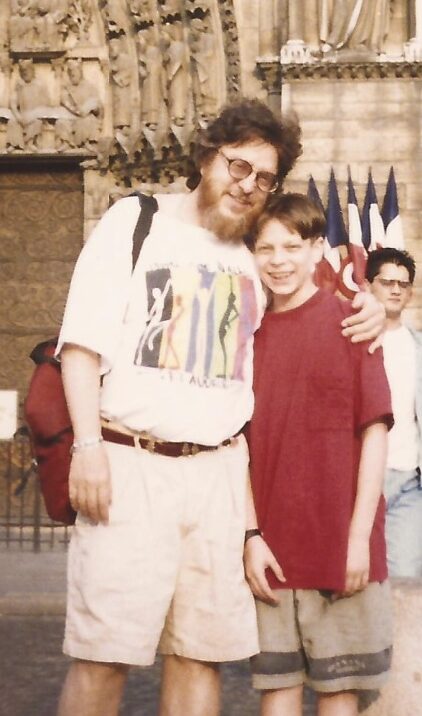

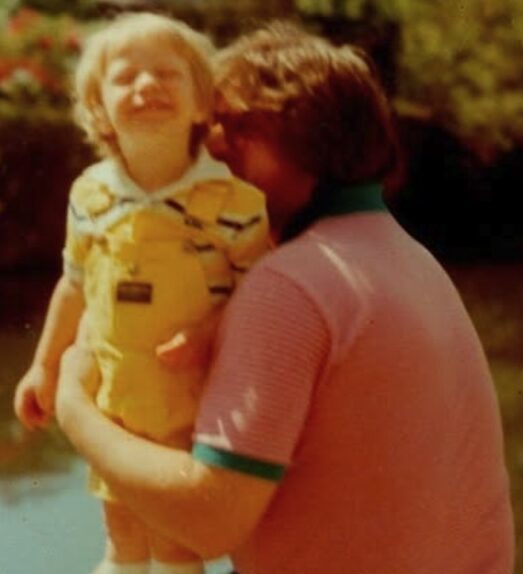

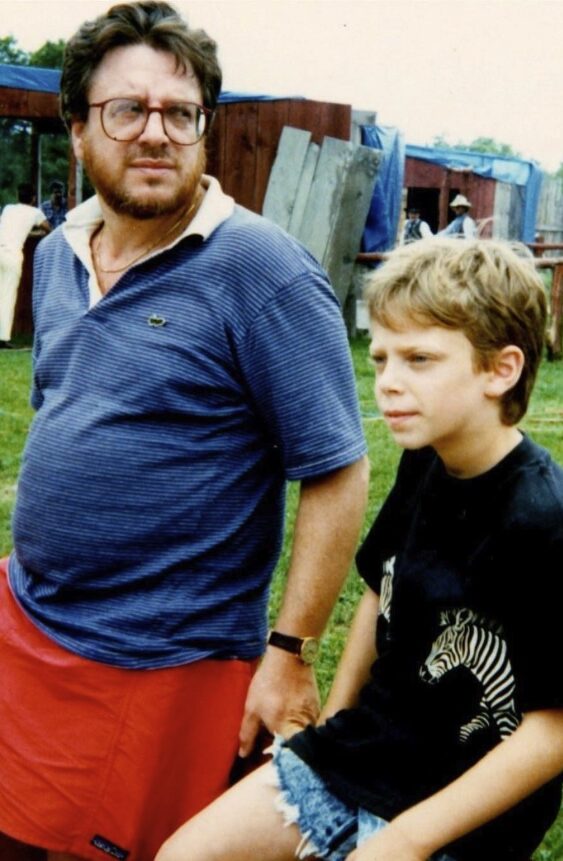

The specter of health, doctors, and medicine hung over my life in invisible ways. My father was sick when I was growing up. He had hepatitis C, and he had had two liver transplants, one when I was 13 and one when I was in my late 20s.

I probably didn’t realize it back then, but I was always very concerned about my health. I believed in hospitals and doctors because I saw them save my dad’s life when I was young. I would get physicals, and I liked going to the doctor.

How I Found Out I Had Polycythemia Vera (PV)

I got myself a routine physical in L.A. when I was 26 or 27. My blood counts came back insanely high. I didn’t know what that meant.

I was alone here in L.A. My family was back east. They told me to see a specialist.

I went to a hematologist. She performed a bone marrow biopsy. She tapped into the base of my spine, into my hip.

I gritted my teeth while they went in there and sucked the marrow out of the bone. It hurt so bad, and it felt like they sucked the soul out of my body. The whole thing was just chaotic and scary, and I didn’t know what to make of it.

The diagnosis came back. I had PV and a JAK2 mutation, too. I didn’t know what any of that meant, but I knew who to consult.

I had this relationship with the hospital that saved my dad’s life. As a matter of fact, my whole family had a relationship with this angel of a coordinator in the transplant department.

Her name was Claudette. I emailed her and said, “This weird thing is happening to me. Which doctor can I trust in your hospital?” She said, “We have the best,” and introduced me to Dr. John Mascarenhas.

The diagnosis came back. I had PV and a JAK2 mutation, too. I didn’t know what any of that meant, but I knew who to consult.

Putting My PV Diagnosis in Perspective

My diagnosis made me anxious and nervous. But Dr. Mascarenhas made me feel confident and contained. He made me feel like there was a team behind me. He literally said, “I got you, I got you.” That made me feel cared for.

I think the idea of having a slow-moving blood disease that may or may not progress is more about living with uncertainty and the anxiety it produces. My diagnosis was like a bomb that goes off under the ocean and touches off all of these ripples.

Throughout the 17 years of my life after my PV diagnosis, I felt anxiety and uncertainty and experienced highs and lows that were mostly beneath the surface. But for the first few years, I was almost able to pretend I didn’t have PV. I just had to do my treatments: phlebotomies or blood draws, and aspirin.

Later on, more significant things took place that revealed themselves slowly, as opposed to an acute, huge reaction. But Dr. Mascarenhas saying those things really helped me at the outset.

He said, “PV is a blood cancer, but don’t freak out about that word. It’s a myeloproliferative [neoplasm] — it’s characterized by excess production of blood cells.”

“PV is something you die with, not from. You’re young, and most people get PV when they’re older. So, you’re talking about 20 years of quality of life, but you’re 27 years old, so you’ve got a lot of life to live.”

“We’ll manage this and stay on top of this together. You’re going to get phlebotomies every six weeks, and you’re going to take baby aspirin.”

Managing My Disease — and Anxiety — for 17 Years

I’ve gotten used to those treatments for polycythemia vera. I do phlebotomies every few weeks and continue to take aspirin.

That being said, I carry around an invisible anxiety. Whenever I feel uncomfortable or fatigued, or if I get, say, a bad bruise on my leg, my anxiety spikes. I’d think, “Oh my God, is it progressing?”

But Dr. Mascarenhas helps me deal with that anxiety, too. I would text him, “Something’s happening!” and he would reply funnily, “Shut up. You’re fine, you know.” Something that would immediately diffuse the panic, anxiety, or fear.

I’d say, “Hey, John, I have a big bruise on my leg.” He’d reply, “Yeah, it’s because you’re taking baby aspirin and it’s no big deal.”

If I say, “Hey, John, I’m pretty tired,” he’d go, “Describe your life to me,” and I’d do so. He’d respond with, “Yeah, that would make anyone tired.” And I go, “Could it be the PV?” He’d go, “Yeah, could be.”

So, there’s nothing acute. I think you just learn to live with it.

I certainly do try to take care of myself. I don’t smoke, I go to the gym, and I try to eat decently. I try not to get overweight. I try to drink enough water. My health is at the forefront of my mind.

I’ve basically been stable these 17 years. The numbers may be elevated, but they’ve stayed exactly the same all this time. There’s wear and tear as this disease goes on unmitigated, but at least it’s not getting worse. So thank God for that. I’ve basically been doing what I’ve always done.

Dr. Mascarenhas is the tip of the spear with research and stuff. Every so often, we’ll try a new intervention to see if it’s useful.

I’ve basically been stable these 17 years. The numbers may be elevated, but they’ve stayed exactly the same all this time.

My Father’s Diagnosis Helped Me Navigate My Own

Aside from my polycythemia vera treatments, I’ve also been able to leverage what I’ve learned from my dad’s and family’s experiences to help with my own. Watching them from shore, so to speak, enabled me to navigate this system.

I’ve watched my father and family get by. I’ve seen my mother be a sort of squeaky wheel, with her not-taking-no-for-an-answer attitude. She taught me not to be overwhelmed by doctors and leap into action.

I learned to go, “Alright, something’s going on — so I need to resolve this as fast as possible. Everyone out of my way. I’m not going to wait around. I’m calling everyone I know. I’ll find the best doctor. I’ll double-check all of this. I’ll get in there and befriend all the doctors and nurses.”

It’s the opposite of being overwhelmed by scary information that you’d rather not know. I’m not like that. I’d like to know everything and take it on, so I don’t have to think about it anymore.

Tracking My Symptoms and Integrating PV Into My Life

I don’t particularly track my polycythemia vera symptoms, but I’m quite aware of when something’s wrong, and I go, “John, what’s this?”

I don’t write my symptoms down. But I do have a list or litany of things my team helps me keep abreast of. Night sweats, nausea, headaches, fatigue, and so on. I usually say “No” to most, and sometimes “Yes” to others.

I am not PV. I have it. It’s part of me. It’s not the whole me. Finding that balance is really important.

The more you talk about something or say something, it’s as if you’re casting a spell. I don’t want to talk about PV all the time, as if it’s my whole identity now. I’d rather integrate it into my life by finding that balance between keeping it part of me and making it my entire identity.

I think both of those things are too extreme. Integrating it, I think, is a useful way to navigate your world.

I don’t want to talk about PV all the time… I’d rather integrate it into my life by finding that balance between keeping it part of me and making it my entire identity.

Building a Relationship With My Care Team

Being a great doctor is a lot like being a director in terms of how they coordinate and communicate.

As a director, I have to shape-shift all the time. Every actor needs to be spoken to differently. Some like to rehearse a lot while others like to improvise. Some actors like to be really serious while others like to joke. Some like a lot of attention while others want to be left alone, and they don’t tell you that. You have to intuit it.

So if you’re on a shoot day and you have eight actors and each has a different way of working, one of the big parts of your job is to be able to bounce around and know how to deal with them all, while you’re doing a thousand other things.

It’s difficult. The best doctors work like directors, working seamlessly with people. It’s not a one-size-fits-all thing, and I guess if you feel like your doctor’s not doing that, you could say something.

The hardest part of the job is that many patients are a handful. They’re in terrible moods. They’re angry. They’re grouchy. Of course, they’re in pain. They’re really scared.

You can’t expect consistency and elegance when someone is in fear and pain. But as a patient, if you meet a new doctor, you’re trying to get diagnosed, but you’re also trying to forge a relationship. So you can also show up in a way that makes them want to work with you.

When I met Dr. Mascarenhas for the first time, I wanted to be his and the nurses’ favorite patient. I wanted them to be relieved when I’m on the schedule. That’s partly my nature; I joke around, and I try to keep it light and funny.

But it’s also because being easy to deal with helps foster a stronger relationship with someone than if you show up yelling and acting as if you know what to do. It goes both ways, even though the doctor’s got all the power in that situation. But a patient can also do a lot.

I’m Living My Life

One of the great things that Dr. Mascarenhas said to me when we first met was, “Managing polycythemia vera is all about quality of life, but it’s your life, so get out there and live it. Don’t sit around and panic all the time.”

I feel very viscerally about that. Seeing my father progress through his illness might have had something to do with it — as well as having my own issues.

I feel very strongly that you only get a certain amount of time here. And even if your health is compromised, you’ve still got that finite amount of time.

We can see it as straddling the line between the healthy and the sick. Every six weeks, I go to an infusion center that’s full of people getting treatments. Then I come back into this other world where health isn’t a concern and everyone’s focusing on making money and having families instead.

It makes you live with more gusto. You never know when things could worsen. I could learn that my PV is progressing, that it’s getting worse, that I need a bone marrow transplant, or something like that.

And so, for as long as I’ve got this body and this energy, I want to throw myself into the world, because it’s so clear that things won’t last forever.

Weirdly, I feel this is the blessing of having a disease like this. It makes it obvious that your life is not forever — which can be all too easy to ignore when you’re healthy, and then you can just take things for granted.

I had to learn to manage my anxiety in my mind and body. The gym, meditation, therapy, acupuncture, and attending long silent retreats are all helpful. Those are a whole scaffolding of things that help manage fear.

I feel very strongly that you only get a certain amount of time here. And even if your health is compromised, you’ve still got that finite amount of time.

Why I Share My Story

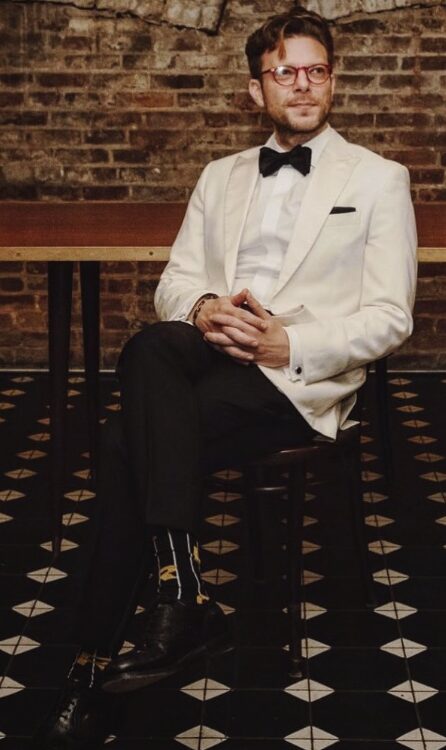

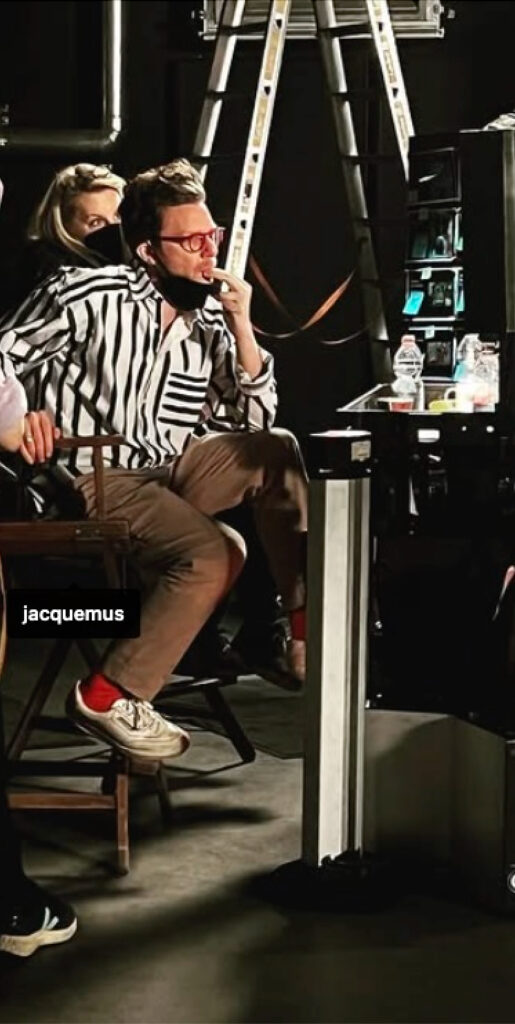

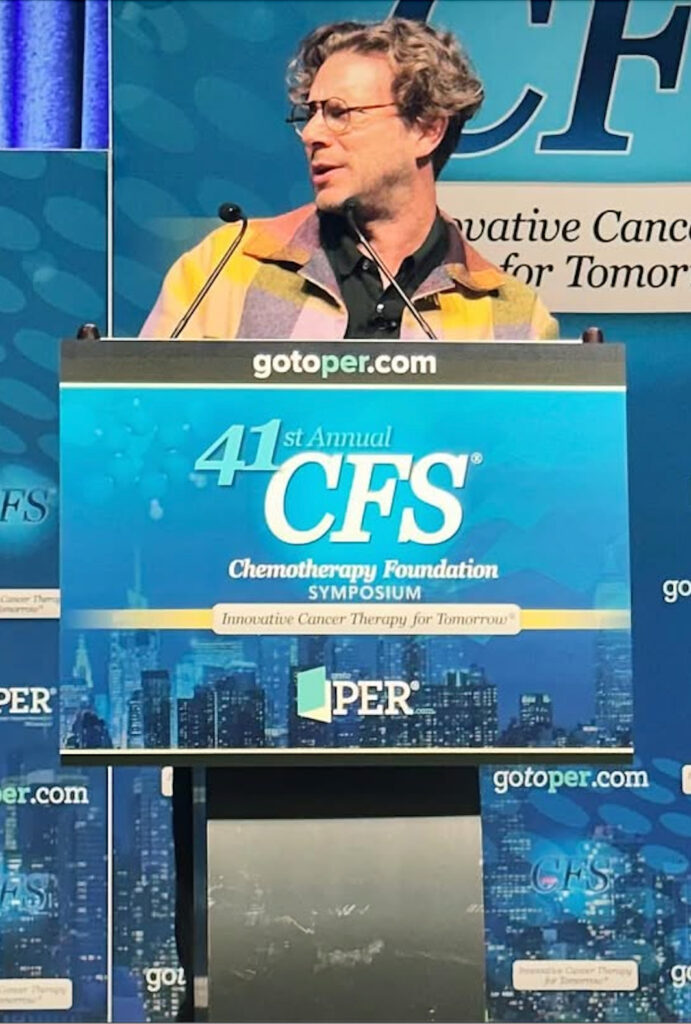

Dr. Mascarenhas asked me if I would want to speak at this blood cancer gala in New York. “It’s kind of a big deal,” he said. “Bradley Cooper was going to speak, but he had to back out. Would you want to do it?”

I accepted the invitation. I wrote a funny speech that was as honest and vulnerable as I could muster. I don’t think I realized how profound it was going to be until after I had delivered it. It felt a little lonely, though; no one was with me as I did it.

Having polycythemia vera was never something that I kept a secret. I thought that having it as a shameful secret actually felt like a whole other kind of cancer. Just some other thing that you’re burying down that’s only going to start to curdle.

I made videos that were kind of an extension of that speech. They were unique opportunities to process all of this stuff through my art form. I thought it would be great to gather a crew and be on camera, and tell my story.

The premise of the videos was that Dr. Mascarenhas and my care team are fighting for my quality of life. And so the videos would involve Dr. Mascarenhas going on a date with me, basically, for a crazy day in New York, and actually see the life he’s saving. He wouldn’t know what I had planned for that day — a trapeze class, or diving, or driving a convertible, or taking a tango lesson. I see him at his job when I consult him — and this would allow him to experience my life firsthand.

Dr. Mascarenhas was quite eager to do it. Getting to have that time with him was pretty important for our relationship, and was certainly unique. Of course, a lot of patients wouldn’t be able to do anything like that with their doctors, but our banter is really quite evident in the video.

Part 1: “Get Out There and Live It”: A Doctor-Patient MPN Story

Part 2: Join an MPN Patient and his Doctor on an NYC Adventure

I’m hoping the video can serve as a model for other patients and doctors, too.

My Advice for Those with PV or Another MPN

Everyone’s MPN is different. You have to get a great team of doctors together to help you somehow, because you can’t do it alone. It also makes you feel so much more at ease when you feel like someone’s got you.

I think being aware of your body is important, but having a disease makes you pretty aware of your body already.

When you learn that you have a disease like polycythemia vera or another MPN, you can buckle under the strain and complain, “Why me?”, pull away from the world, and become a hermit. Of course, I sometimes do that, and wish I didn’t have to deal with this and that I could just be carefree.

But, you see, PV can be viewed as a gift. You can use it as a way to be as present in your life as possible. Because you can be hyper-aware of how fragile your life really is.

And so that would be my advice: to see PV or another MPN as a gift — and to figure out that there’s a gift within every experience, even terrible ones.

It’s your job to figure out precisely what that gift is. What’s that experience giving you? What’s it teaching you? How can you make something good from it?

Not to be a Pollyanna about it. To be honest, it’s not all roses. It doesn’t feel good to get phlebotomies all the time, to have to go to the doctor frequently, or to be unable to go on vacation for longer than a few weeks at a time because of my phlebotomy regimen.

It’s a pain and it’s lonely. But it sets you apart and makes you unique. It gives you a unique access point to life.

That would be my advice: to see polycythemia vera or another MPN as a gift — and to figure out that there’s a gift within every experience, even terrible ones… Not to be a Pollyanna about it. To be honest, it’s not all roses.

Special thanks again to Incyte for supporting our patient education program. The Patient Story retains full editorial control over all content.

Inspired by Todd's story?

Share your story, too!

More Polycythemia Vera Stories

Taja S., Polycythemia Vera

Symptoms: Chronic fatigue, fainting, stroke-like episodes, elevated hemoglobin, hematocrit, and platelet count

Treatments: Emergency surgery for ruptured cyst & bowel obstruction, chemotherapy, radiation, bone marrow transplant

Jeremy S., Polycythemia Vera

Jeremy Smith and Dr. Angela Fleischman share empowering insights on living well with polycythemia vera, from symptoms to treatment and patient advocacy.

Todd S., Polycythemia Vera

Symptoms: None, discovered during a routine physical that uncovered extremely high blood counts

Treatments: Phlebotomy, aspirin

Nick N., Polycythemia Vera

Symptoms: None, caught at routine physical

Treatments: Phlebotomy, Besremi