Loriana Hernandez-Aldama’s Cancer Story

Cancer Friends Series with Andrew & Esther Schorr

The Patient Story’s series “Cancer Friends” features Andrew and Esther Schorr. They co-founded a resource for other cancer patients and caregivers to help them through their diagnosis and treatment (Patient Power).

Explore our”Cancer Friends” series on our video channel here!

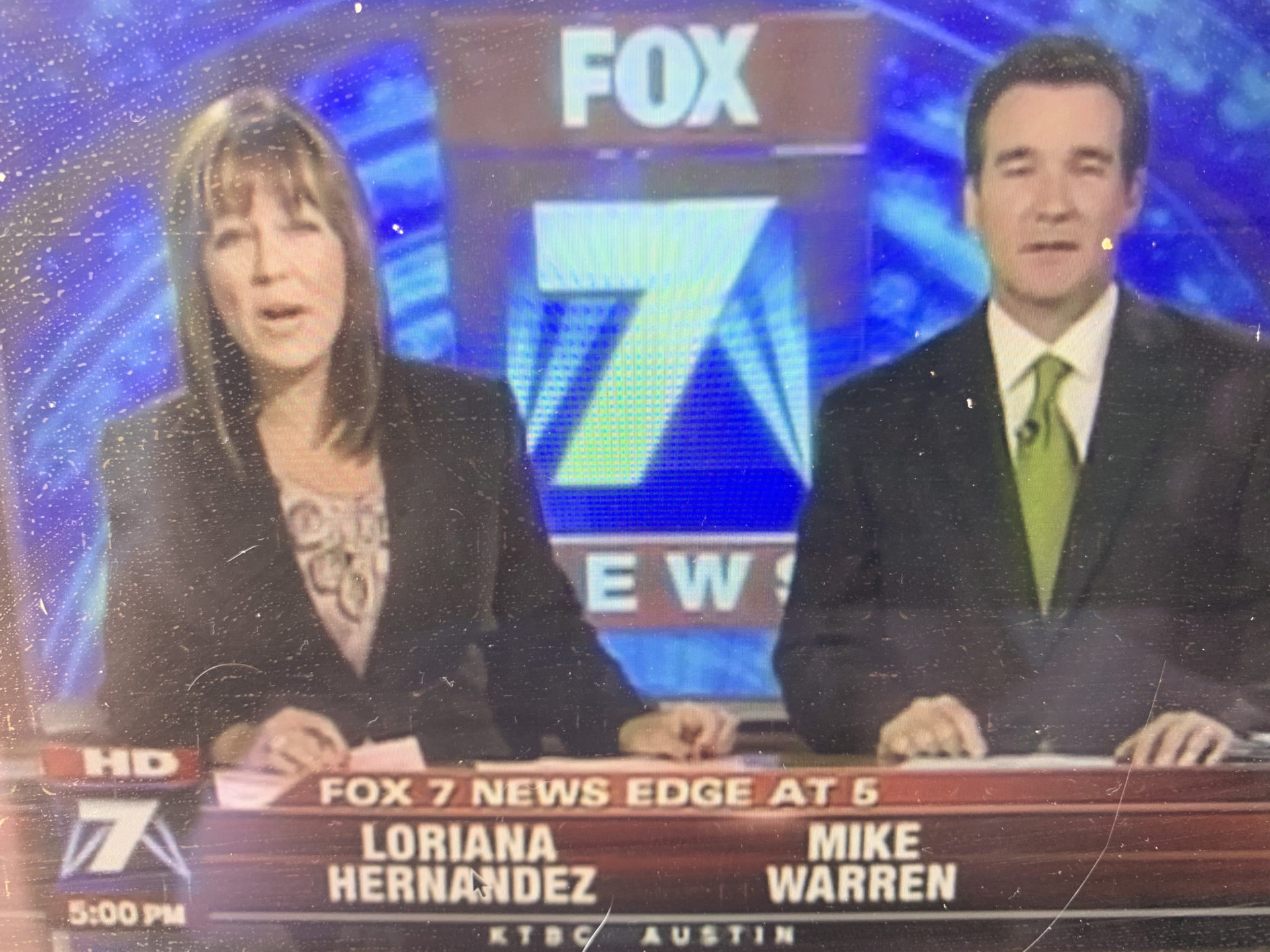

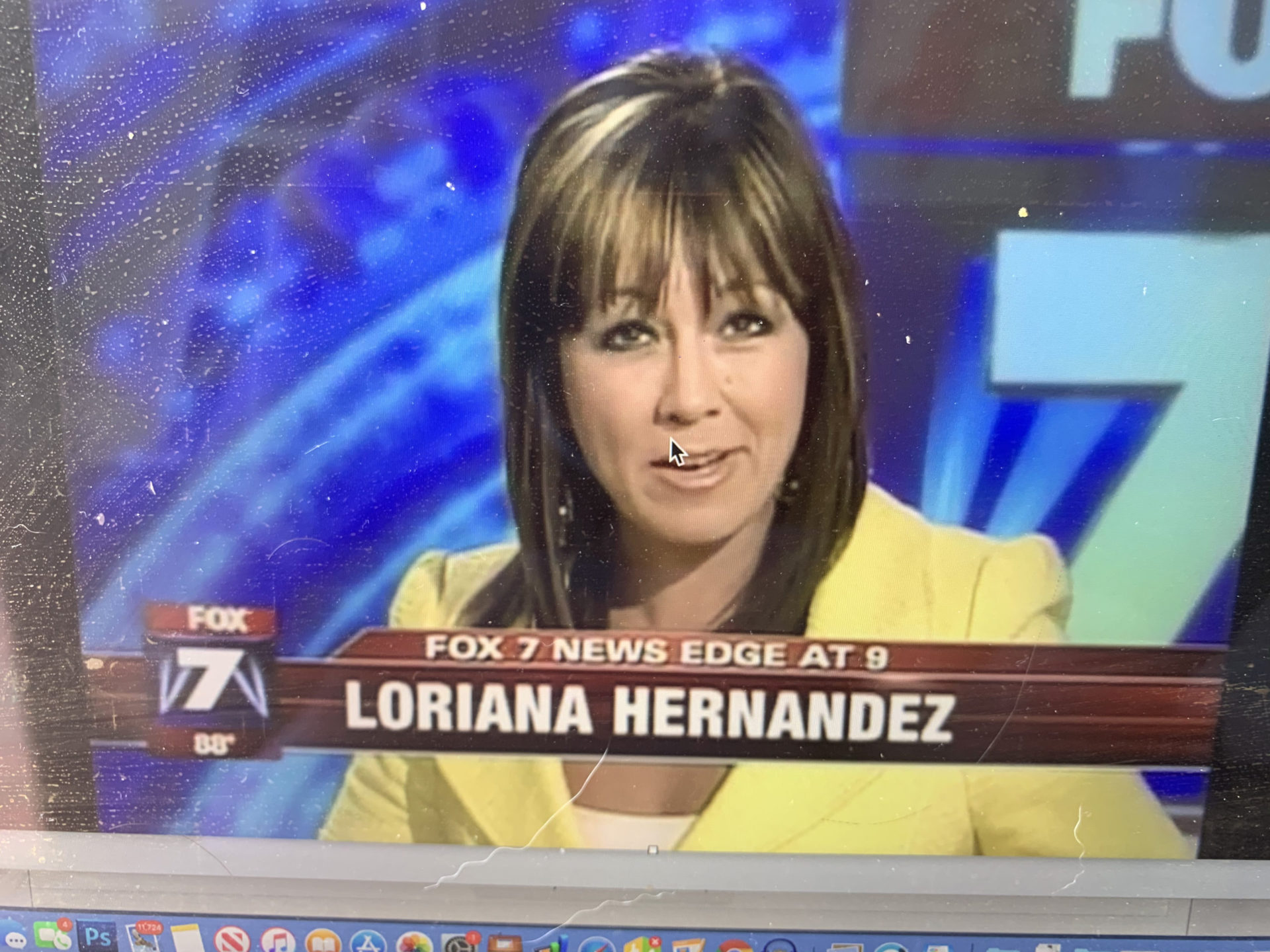

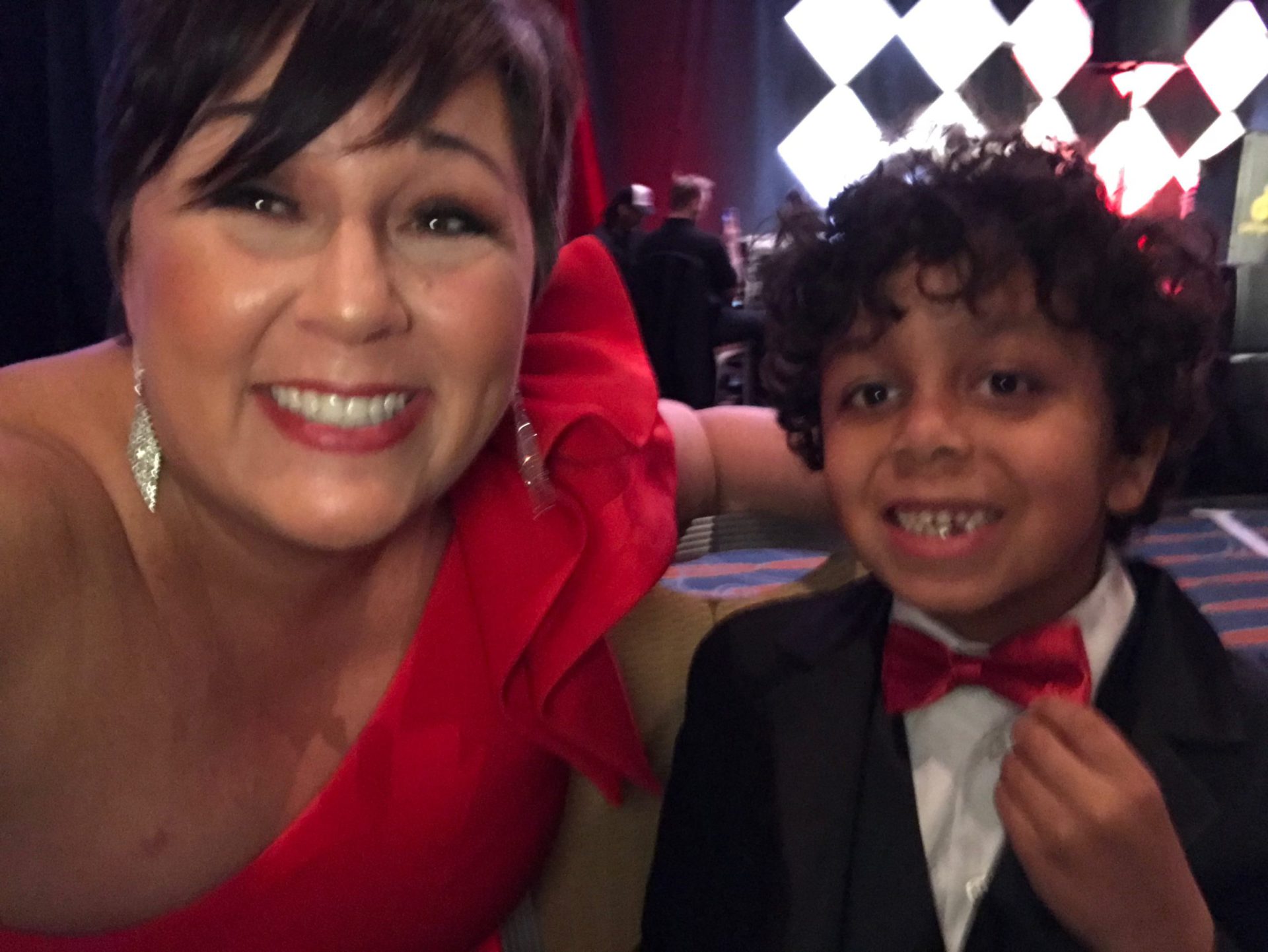

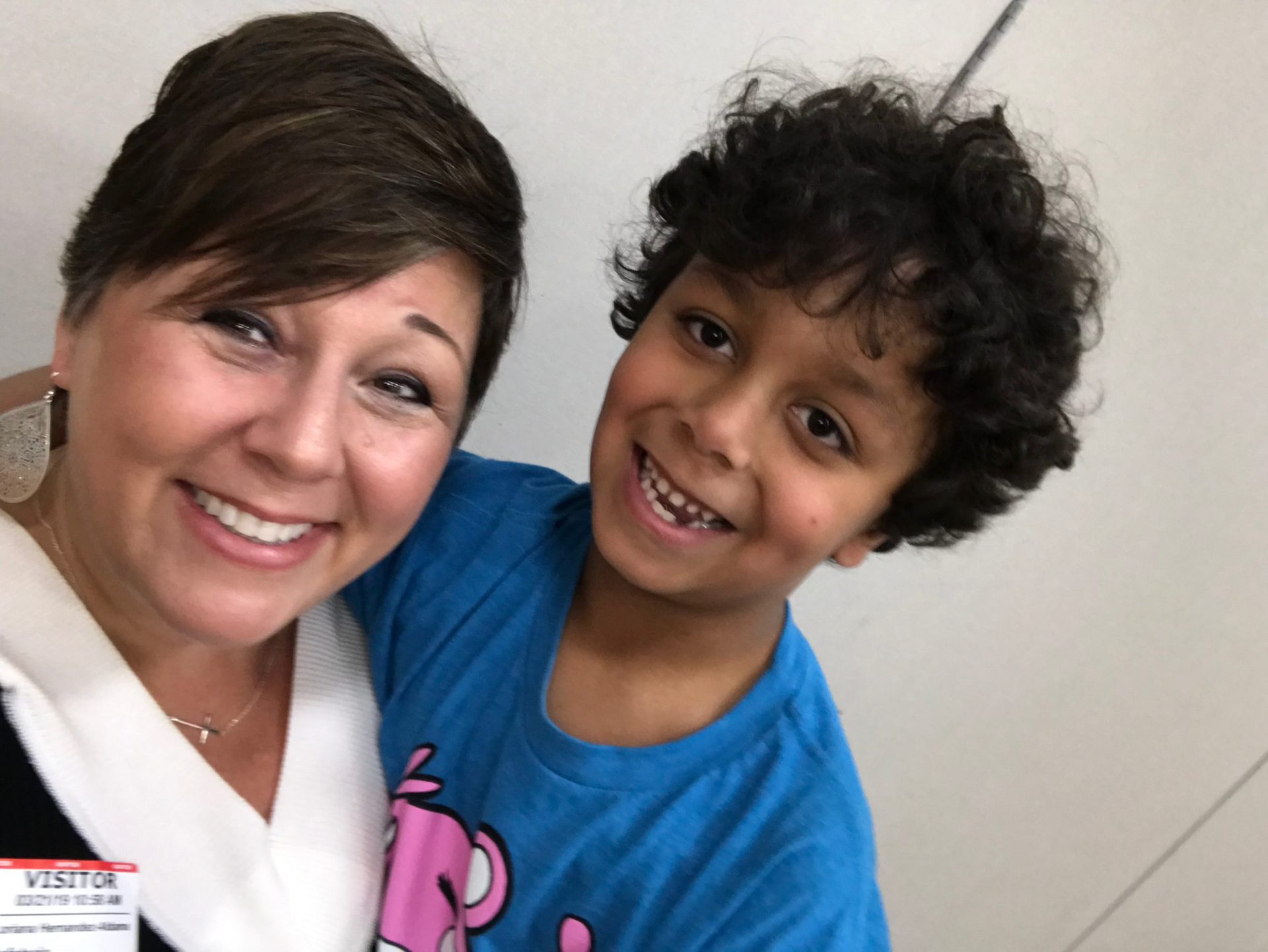

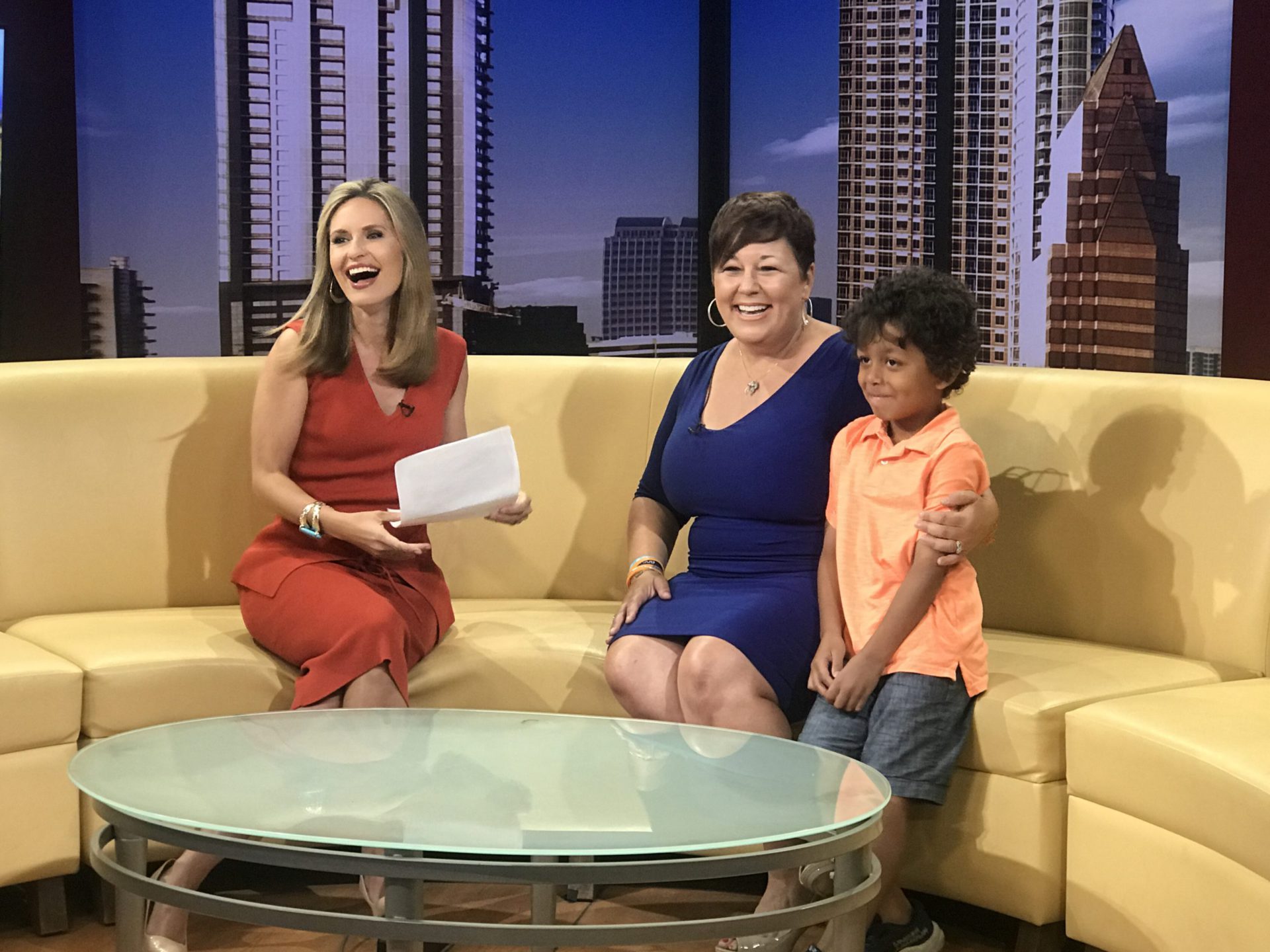

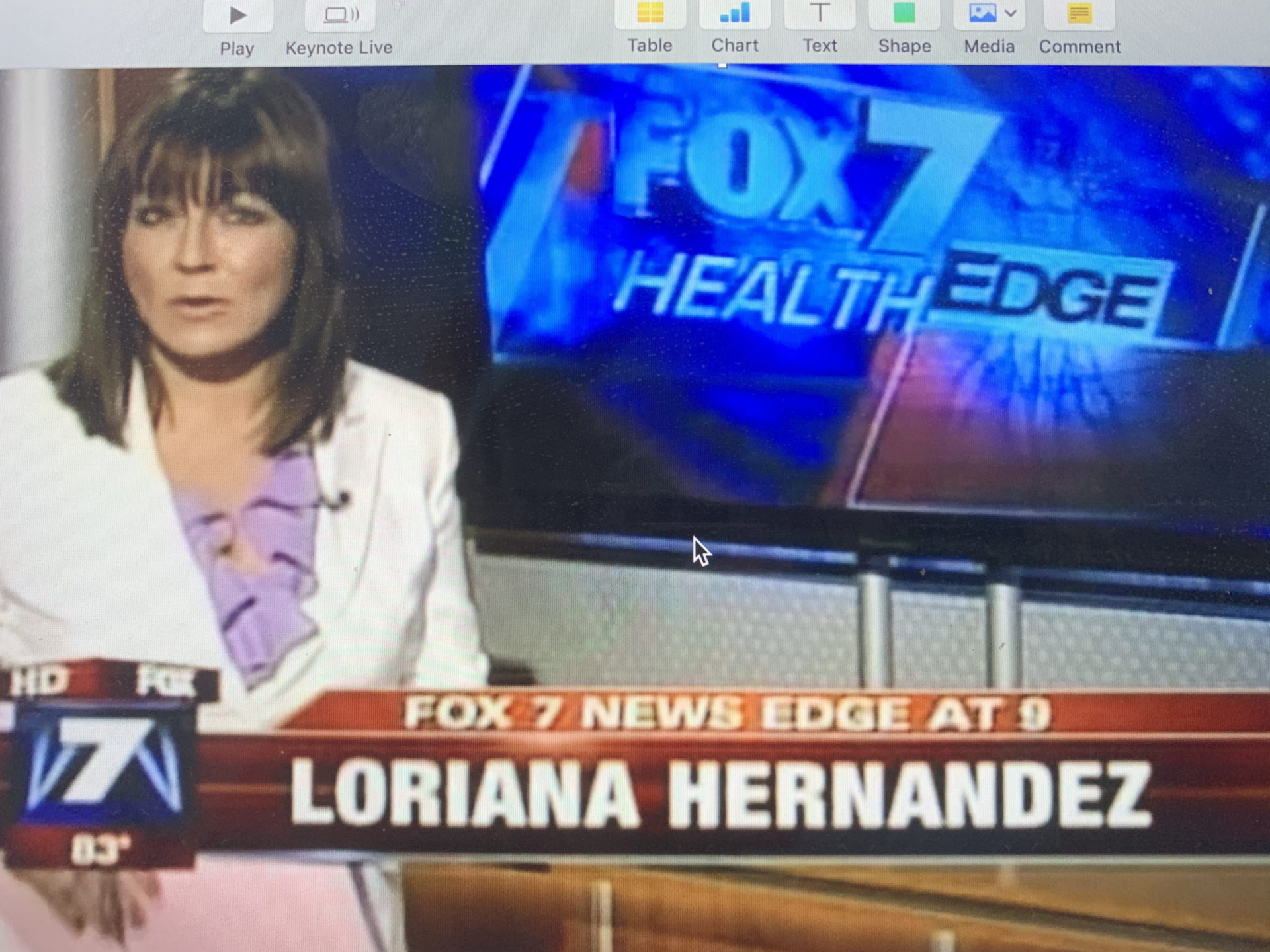

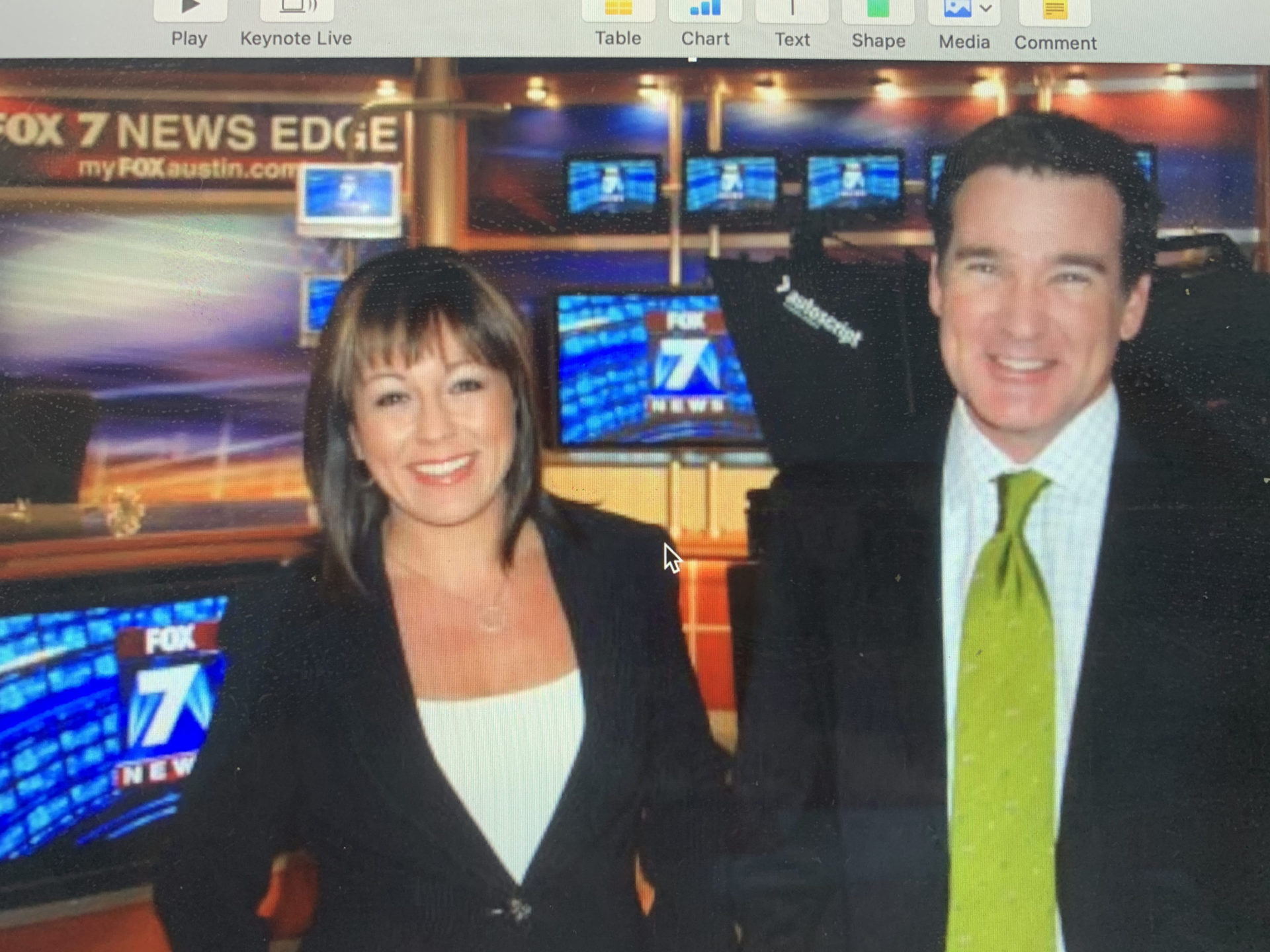

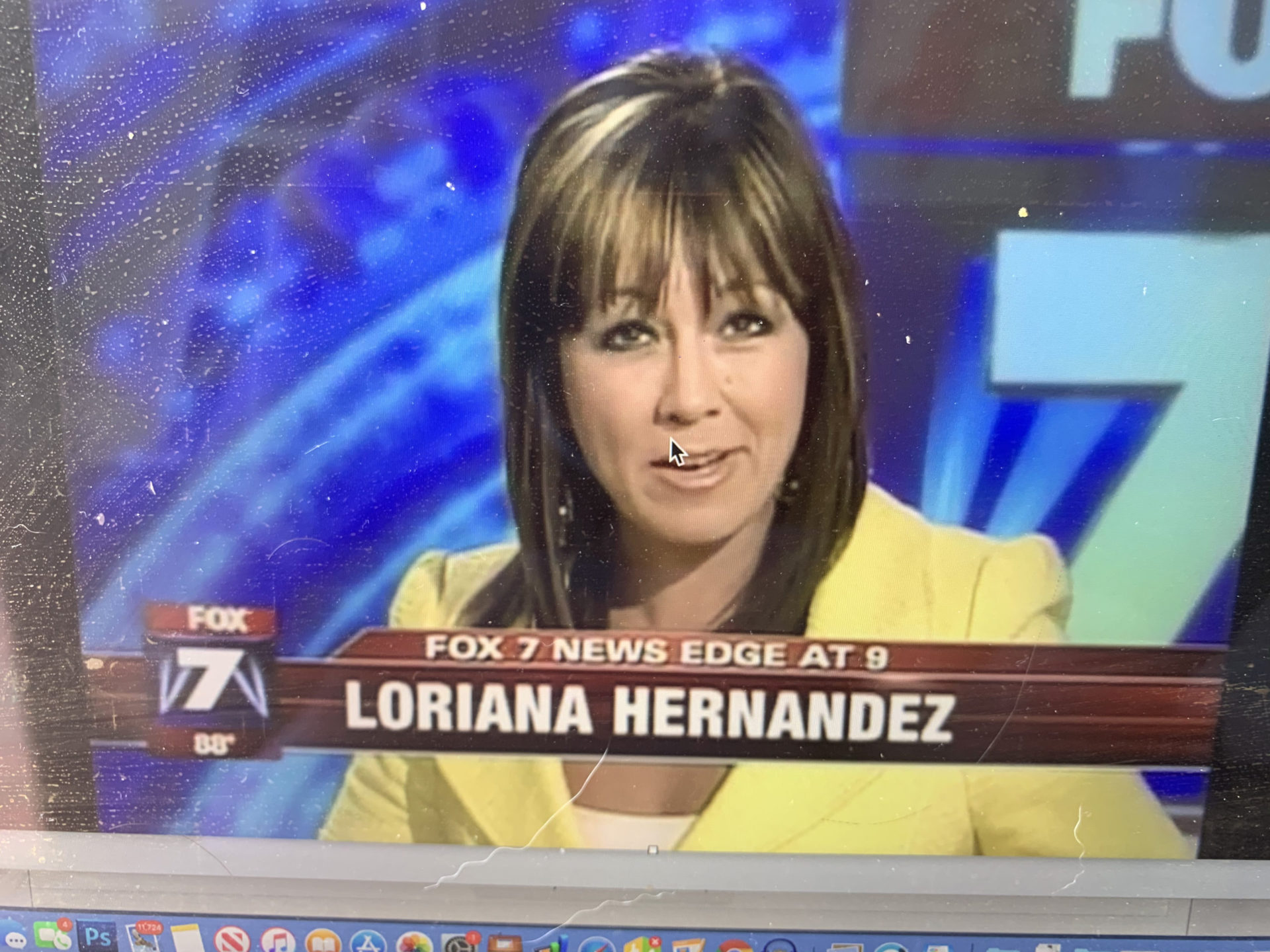

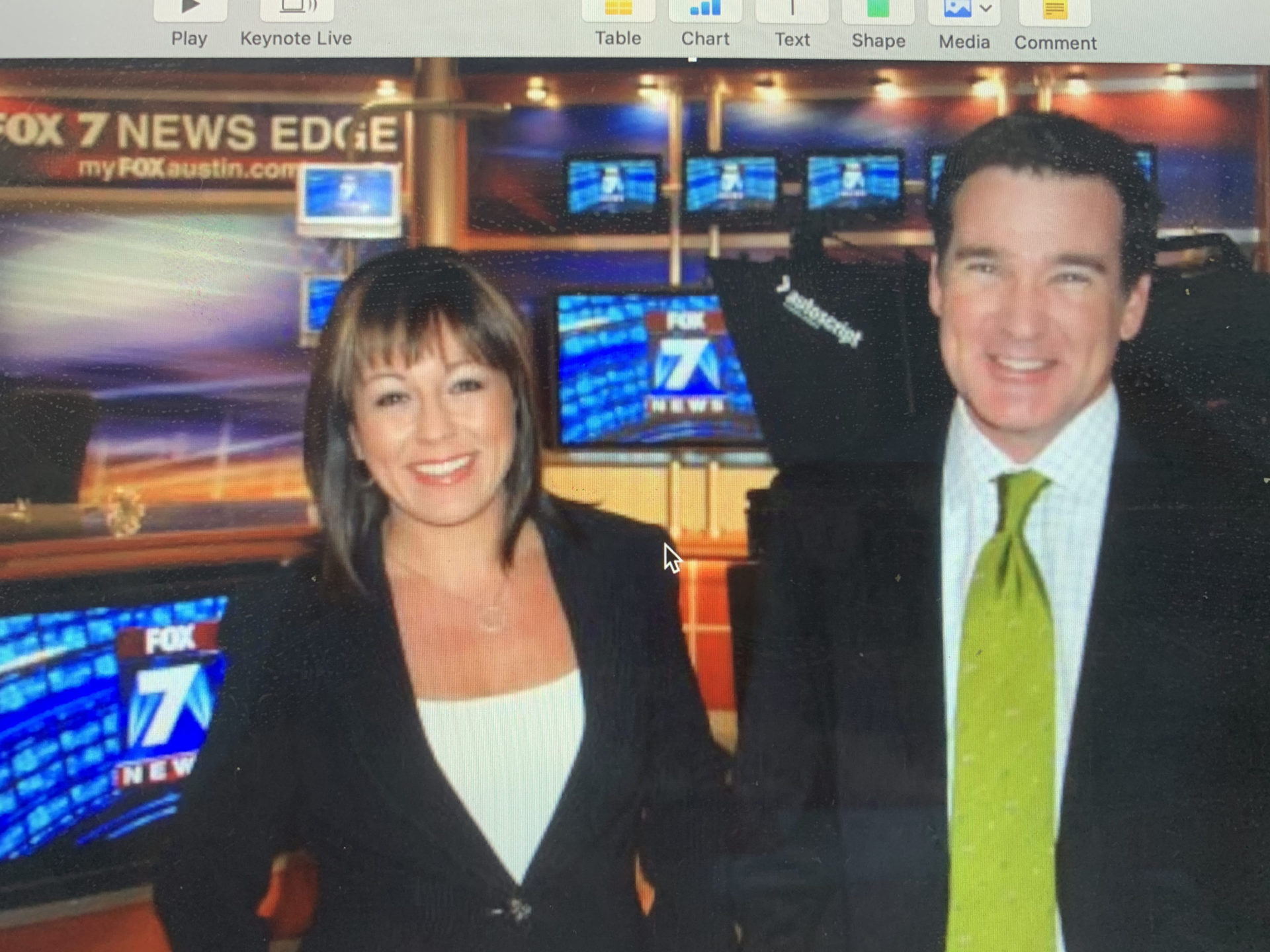

This segment focuses on Loriana Hernandez-Aldama, a 2-time cancer survivor who founded ArmorUp for LIFE. Loriana was an Emmy Award-winning broadcast anchor when she was diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia. After a yearlong fight in the hospital, she was later diagnosed with breast cancer.

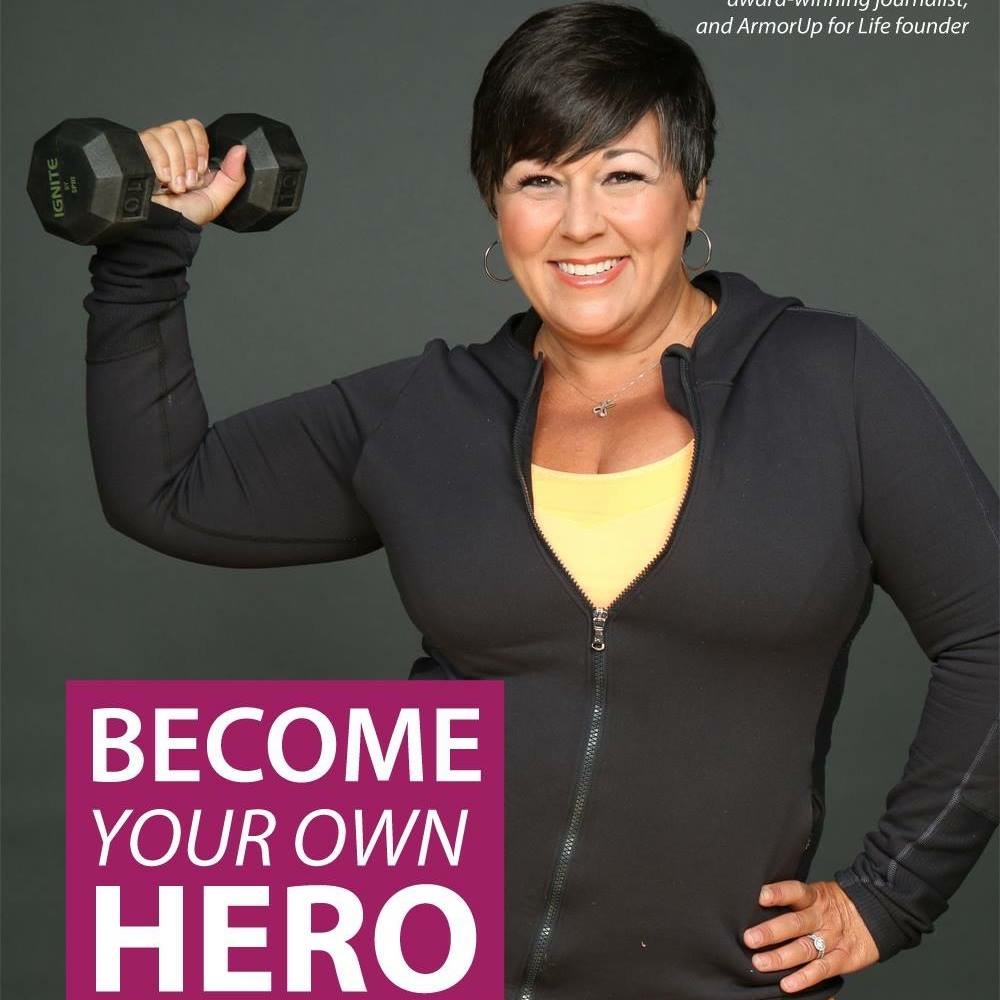

Now, Loriana is a patient advocate and the founder of ArmorUp for LIFE, a nonprofit focused on giving all patients the same access to better treatment options and tools. Loriana is also an advocate for prehabilitation, or taking steps to make our bodies healthier and more equipped to fight cancer.

- Introduction to Loriana Hernandez-Aldama

- Acute Myeloid Leukemia and Breast Cancer Diagnoses

- Gift of Time

- Coping with the Prolonged Hospitalization

- Waving the Flag for Help

- Most Important Support

- Importance of Prehabilitation

- ArmorUp for LIFE

- Increasing Positive Outcomes

- Self-Advocacy

- Second Opinions & Shared Decision-Making

- Helping Underserved Communities

- First Steps for Advocacy

- Advice for Advocates

- Conclusion

This interview has been edited for clarity. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider for treatment decisions.

I cannot sit back and not do anything. I have to help others. If I live, I will serve.

Loriana Hernandez-Aldama

Introduction to Loriana Hernandez-Aldama

Esther Schorr, The Patient Story: Hi, there. This is Esther Schorr with The Patient Story, and I am privileged today to be speaking with a wonderful, wonderful patient advocate and speaker.

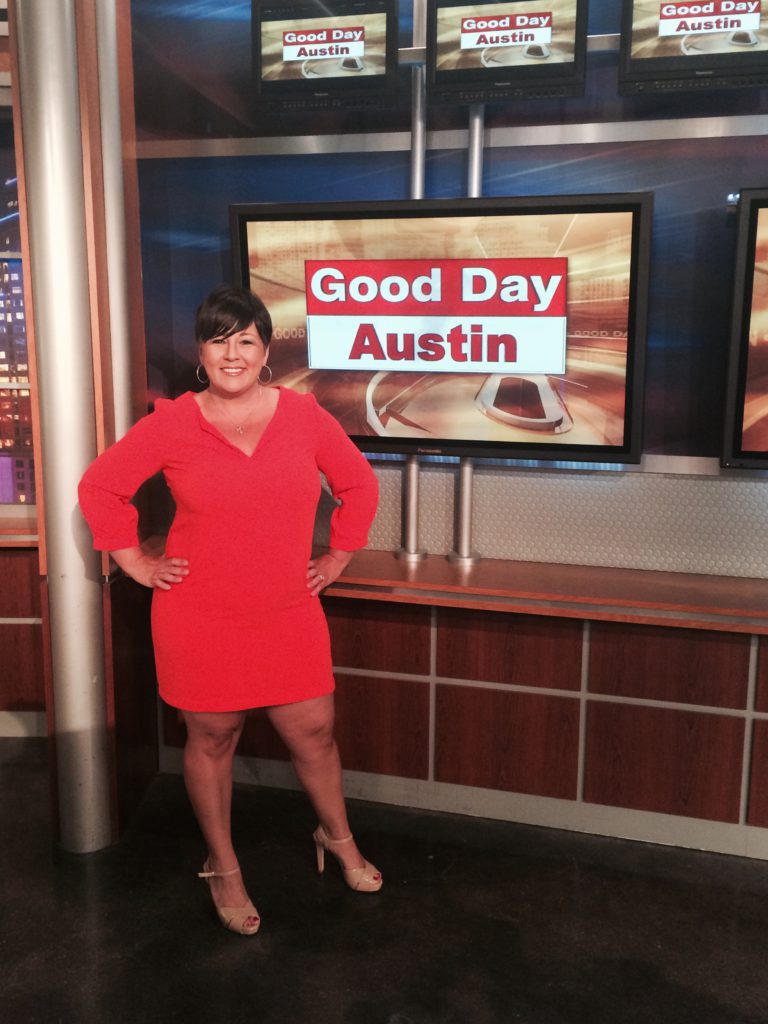

Loriana Hernandez-Aldama is an Emmy Award-winning journalist. She is also a 2-time cancer survivor. She’s a national advocate and speaker, and she’s the founder of ArmorUp for LIFE. Loriana, welcome. I’m so glad that you’re able to give us this time to talk today.

Loriana Hernandez-Aldama: Thank you. I always say I’m so happy to be alive [and] to be able to have these conversations that are so needed to help other patients. Thank you for having me, and thank you for thinking of me.

Esther, TPS: I’m glad you’re here, too.

Loriana: I’m so happy to be here and have my feet on the ground.

Acute Myeloid Leukemia and Breast Cancer Diagnoses

Esther, TPS: Loriana, let’s just talk a little bit about your cancer journey. I know it’s been a long and checkered one. What happened?

Loriana: I was living the life as a high-profile news anchor based in Austin, Texas, doing national fitness and medical stories. In an instant, after dismissing many warning signs that I now advocate about, I was in the midst of trying to have a second baby and then found out that I had AML (acute myeloid leukemia).

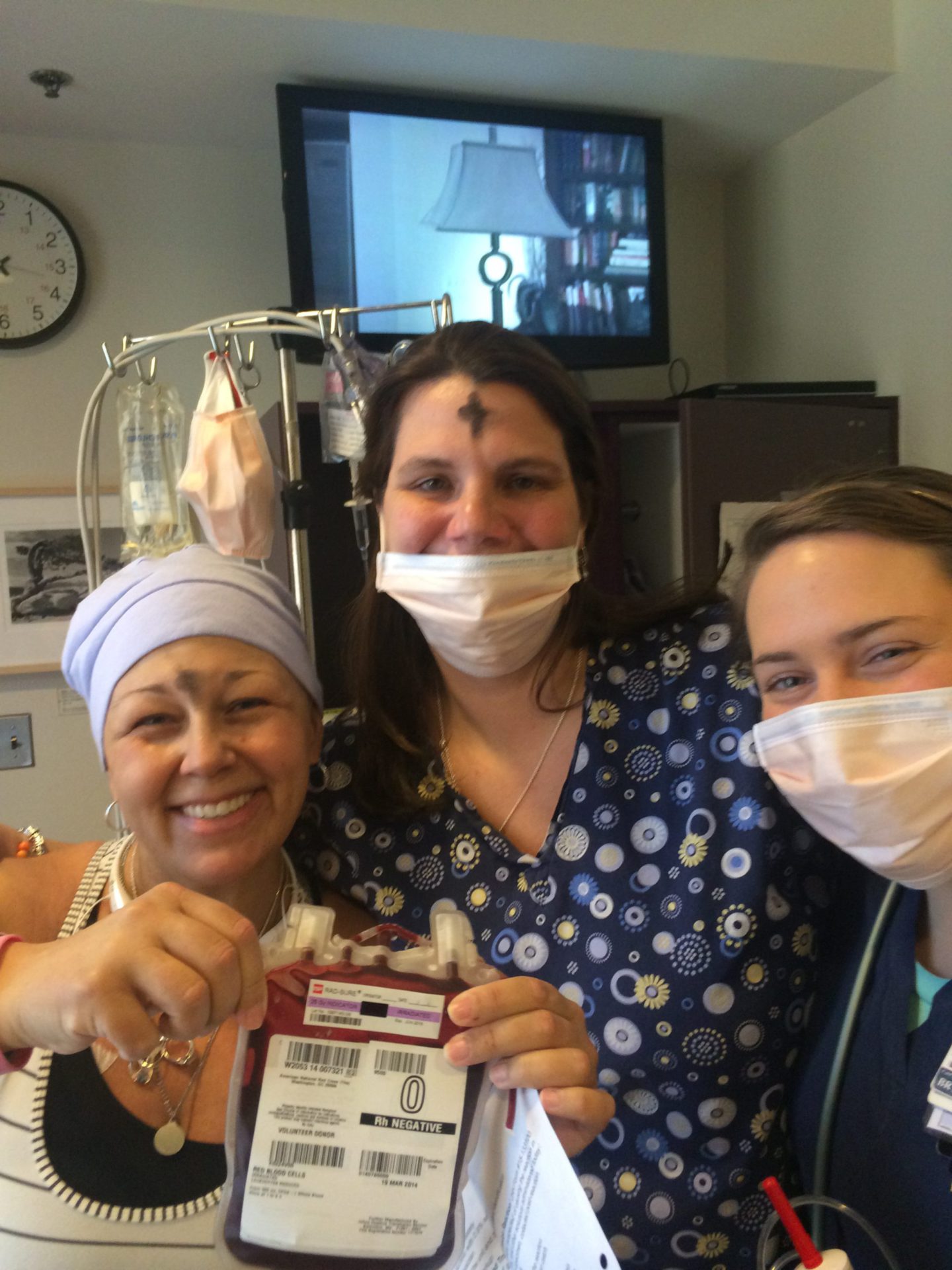

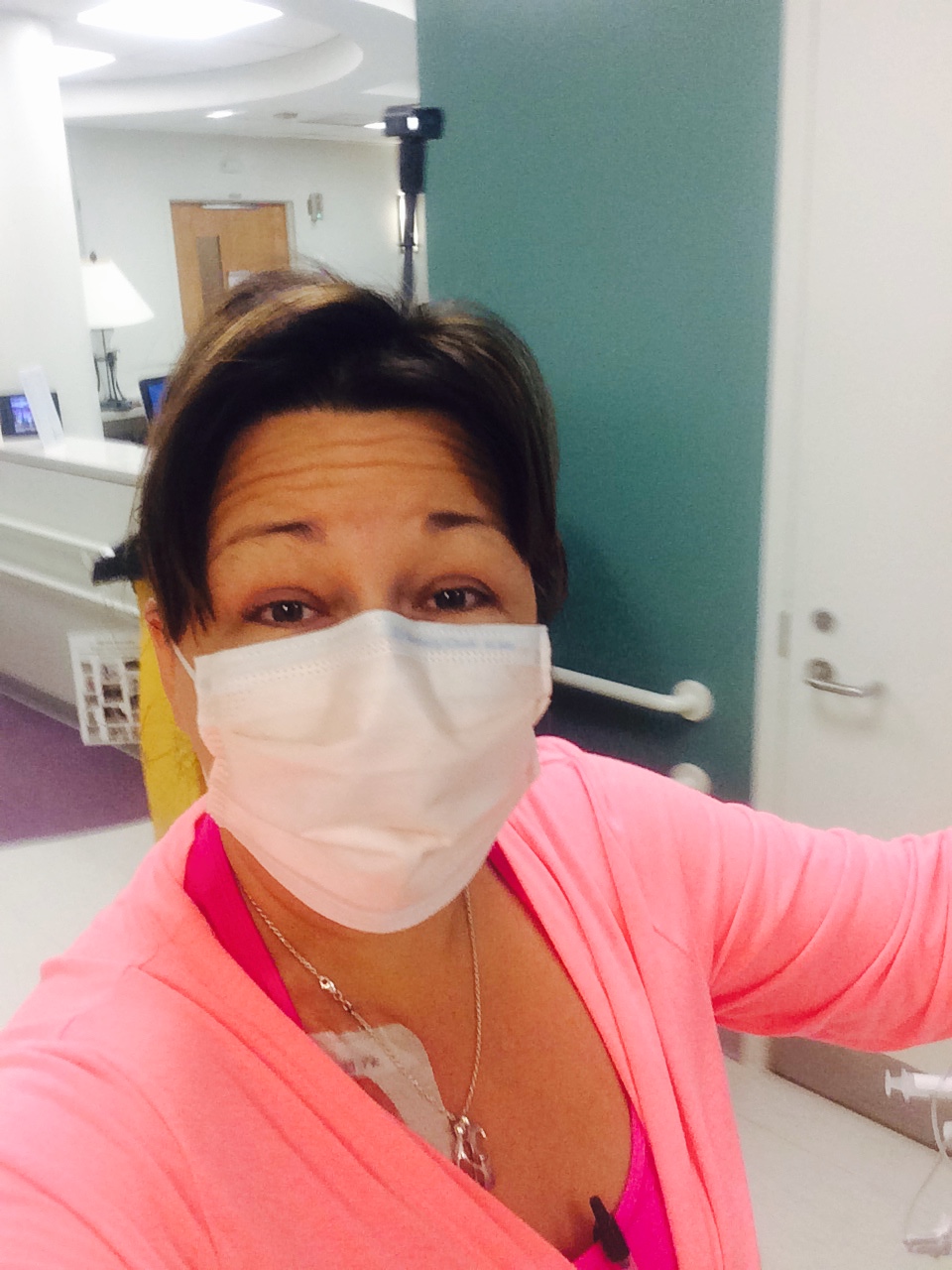

I was misdiagnosed twice. [I] ended up getting on a plane thanks to connections that I had [and] ended up at Johns Hopkins for the fight of my life for an entire year battling AML leukemia.

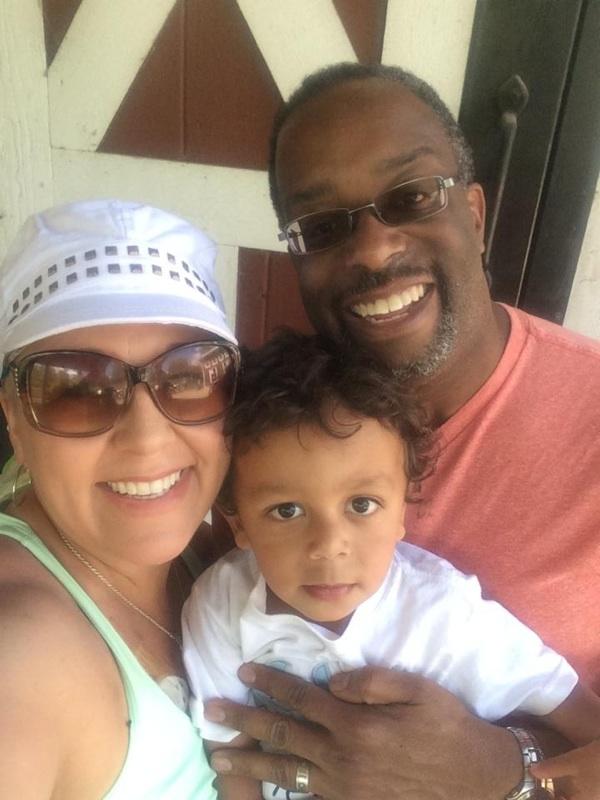

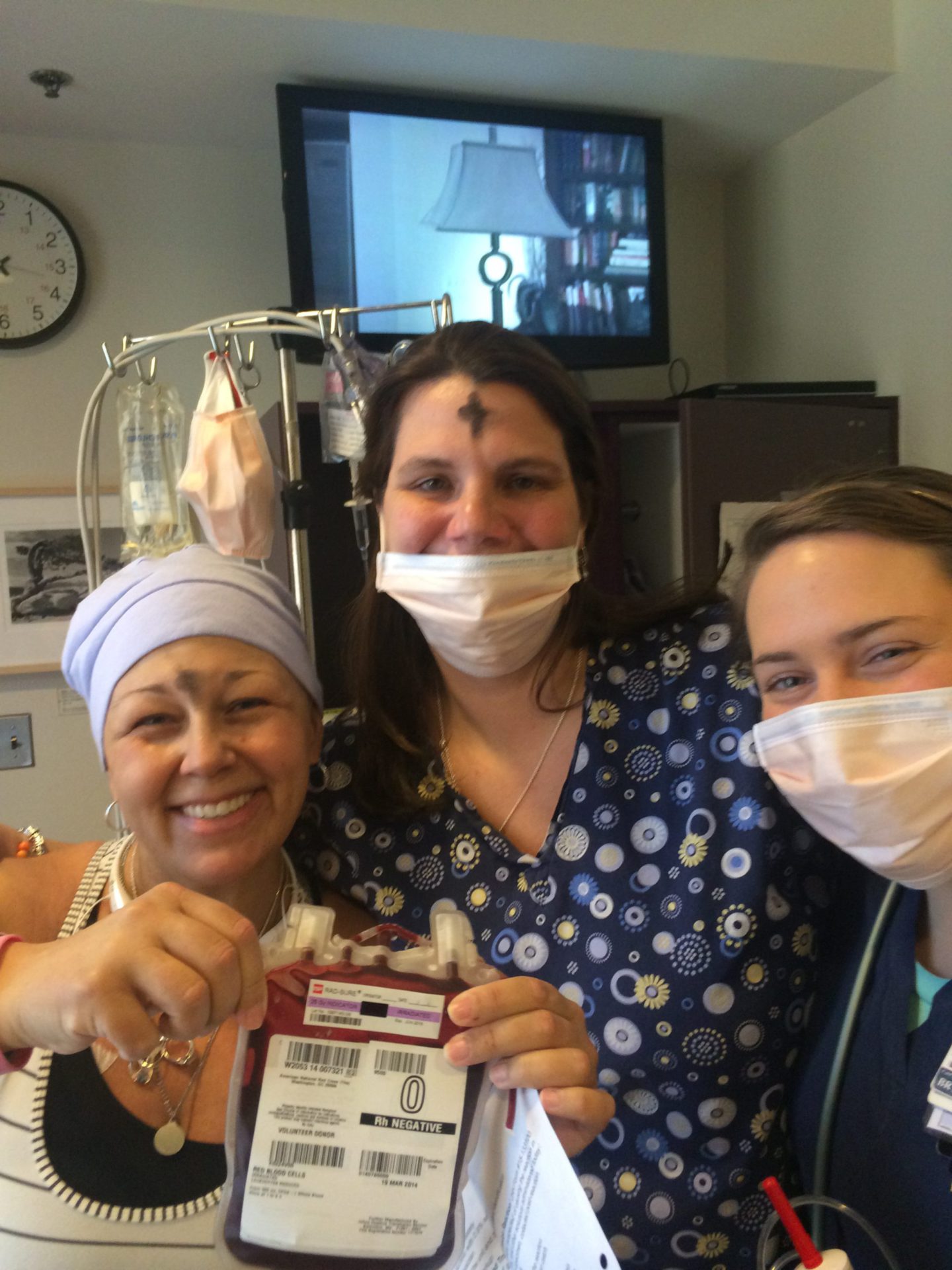

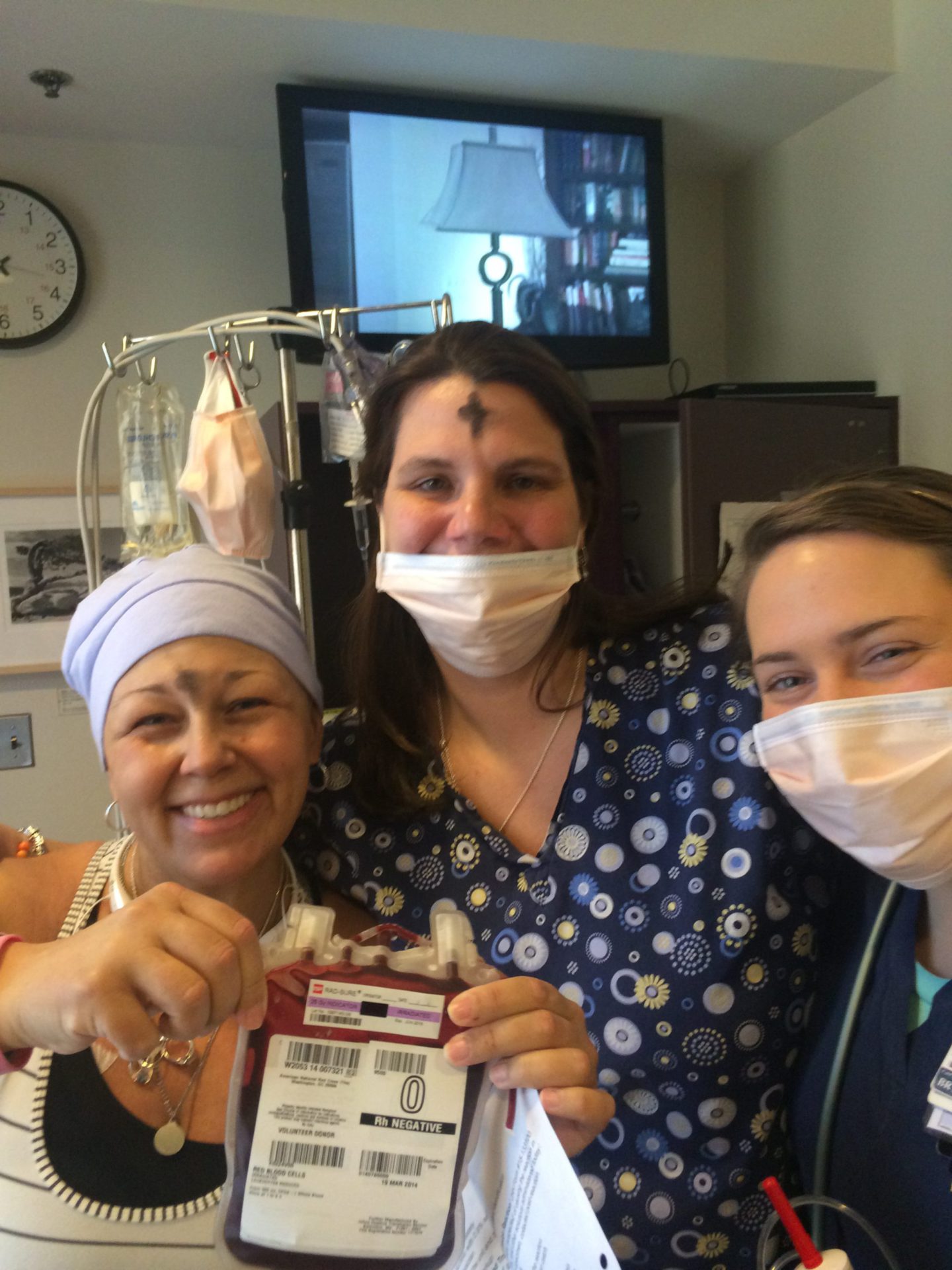

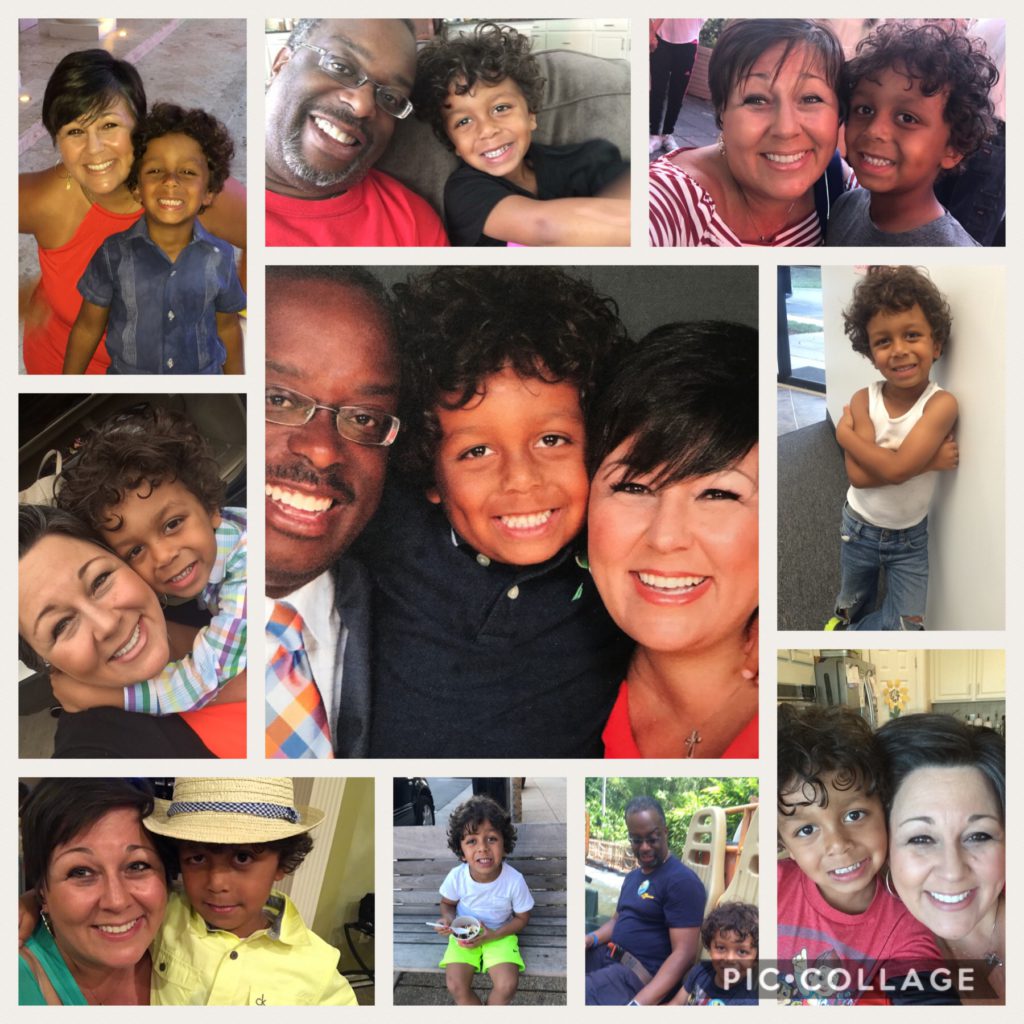

That was real quarantine, separated from my then 2-year-old son. That journey lasted a year. It didn’t work. I needed a bone marrow transplant, so it extended my time away from my son. It’s been a rocky, very tumultuous recovery.

Then 5 years to the day post bone marrow transplant, I found out I had breast cancer. They were telling me, “We probably gave you the gift of time, not the gift of life.”

Because I had no other bone marrow match in the registry, being Latina, my sister was my match. In the genetic markers, she gave me a marker called CHIP. CHIP is a newly discovered genetic marker, which means you’re going to get heart disease.

They gave me back the leukemia marker, and then I got breast cancer. They think it’s either from the full-body radiation or from my sister’s DNA. How do we know that? My sister currently has breast cancer as we speak.

Gift of Time

Loriana: There are tradeoffs with everything. We talk about medicine. It did give me the gift of time. I hope that time is to watch my son grow up and live a long, long life so I can continue to advocate and enjoy my family.

But it has been a very rocky journey. All of that journey, as I was sharing with you, led to a lot of depression and PTSD. Being a journalist, I said, “I cannot sit back and not do anything. I have to help others. If I live, I will serve.” I am living in pain a lot [and] struggling a lot, but I am continuing to serve and really amplify the patient voice.

Coping with the Prolonged Hospitalization

Esther, TPS: How did you and your loved ones cope with this prolonged hospitalization? You went on a complicated treatment journey. You mentioned being in the hospital for a year. How did you cope with that?

Loriana: I look back, and sometimes I wonder, “How did we do it?” What I did was I went into reporter mode, and I started to allocate and delegate roles. I created what I call a pit crew. I actually had to take out a spreadsheet and choose roles just like your church or synagogue [does].

[It was] like, “This person is going to help with my mother and find childcare. This person is going to help with our bills, help me make sure they get paid on time, or help me launch a GoFundMe. This person’s role is for meals.” I really started allocating roles based on what people’s strengths and weaknesses were in a spreadsheet.

I had an advantage. I had the privilege in the sense that I don’t come from a privileged family, but I had connections as a high-profile news anchor. I had a huge pit crew and a huge spreadsheet. When you think of other patients like maybe my sister, who doesn’t have a lot of connections, it’s hard for your circle to help if you have no circle.

»MORE: Mental and emotional support when leaving the hospital

Waving the Flag for Help

Esther, TPS: It sounds like project management was a big piece of that. Whether you have that skill or there’s somebody in your pit crew, it’s getting organized. How am I going to manage this?

Loriana: I say to patients all the time, “You have to wave the flag and ask for help.” Even my sister, as she’s gone through this breast cancer, she’s like, “I’m not an extrovert like you. I can’t ask for help. I’m too ashamed.”

[I’m] saying you have to wave the flag. If you don’t wave the flag, you’re going to put extra burden on me. I can’t make all your meals, and I can’t take it all because I have my own problems, too. I encourage everyone. What I did was create a pit crew of my own support system.

Hospitals now — as I advocate, as you advocate — are starting to learn that we need to build better support systems, but you also have to not rely solely on them. You have to be an equal partner in your own success and be your own hero, in a sense, by humbling yourself and asking for help — whether that is financial help, getting your house clean, getting a meal — because you cannot do it alone.

You have to be your own hero by waving the flag. I had to ask so many people for help — I still do — many times. We could not have done that. My husband ended up losing his job at the end of the 1 year of sleeping at my side and trying to hold down a job that we didn’t want him to lose.

That set him back professionally, [and] we almost lost our house. We’ve gone through a lot. Financial toxicity is huge. My best advice to patients is the minute you get that diagnosis, really lay out what your needs are and how to delegate. If you go to church, think of how they do it in church. So-and-so is working. You have somebody who’s working there [and somebody] who’s in the band.

Whose strengths can you lean on? Section it out so that not one person carries that whole burden. That’s really how we got through it. When I had breast cancer in 2020, that was even harder to ask for help because nobody could come to my house and help.

You have to find ways to do it and find out what advocacy organizations can help you as well.

Most Important Support

Esther, TPS: Out of that whole universe, in your particular situation, what of all those things were the most important support for you?

It’s all important, but if you had to talk about a few things that somebody who’s newly diagnosed needs to focus on — I need these things — what were the things that came to the surface that were the most helpful to you and your family?

Loriana: Unfortunately, it was the GoFundMe, and a GoFundMe is not a plan. We don’t think of that when we think of preparing for illness [or] when we do retirement plans and other plans. We needed a GoFundMe, or we were going to lose our house.

I needed that money to help my 75-year-old mother raise my 2-year-old son for a year. The GoFundMe was so important, and we need to work on a better way to support patients because I was really caught in a unique situation. I always say if you’re not underserved when you start with cancer, you might be when you’re done because the bills start to mount.

I didn’t qualify for anything because they were basing it on my salary as a news anchor. I had no help, but we had no income. After spending a year in the hospital, you’re thinking hundreds of thousands of dollars [of debt]. We qualified for nothing. We had to rely on friends with a GoFundMe. Everybody should raise money in some capacity, and it’s okay to do that.

Esther, TPS: Don’t be embarrassed.

Loriana: No, you should not. I always say to people, “You never know when my story will be your story, and somebody else’s story could be their family’s story.” If you pay it forward, if you skip one coffee at a Starbucks and you donate $5 to someone’s GoFundMe, it may come back to you. It will come back to you in some other way.

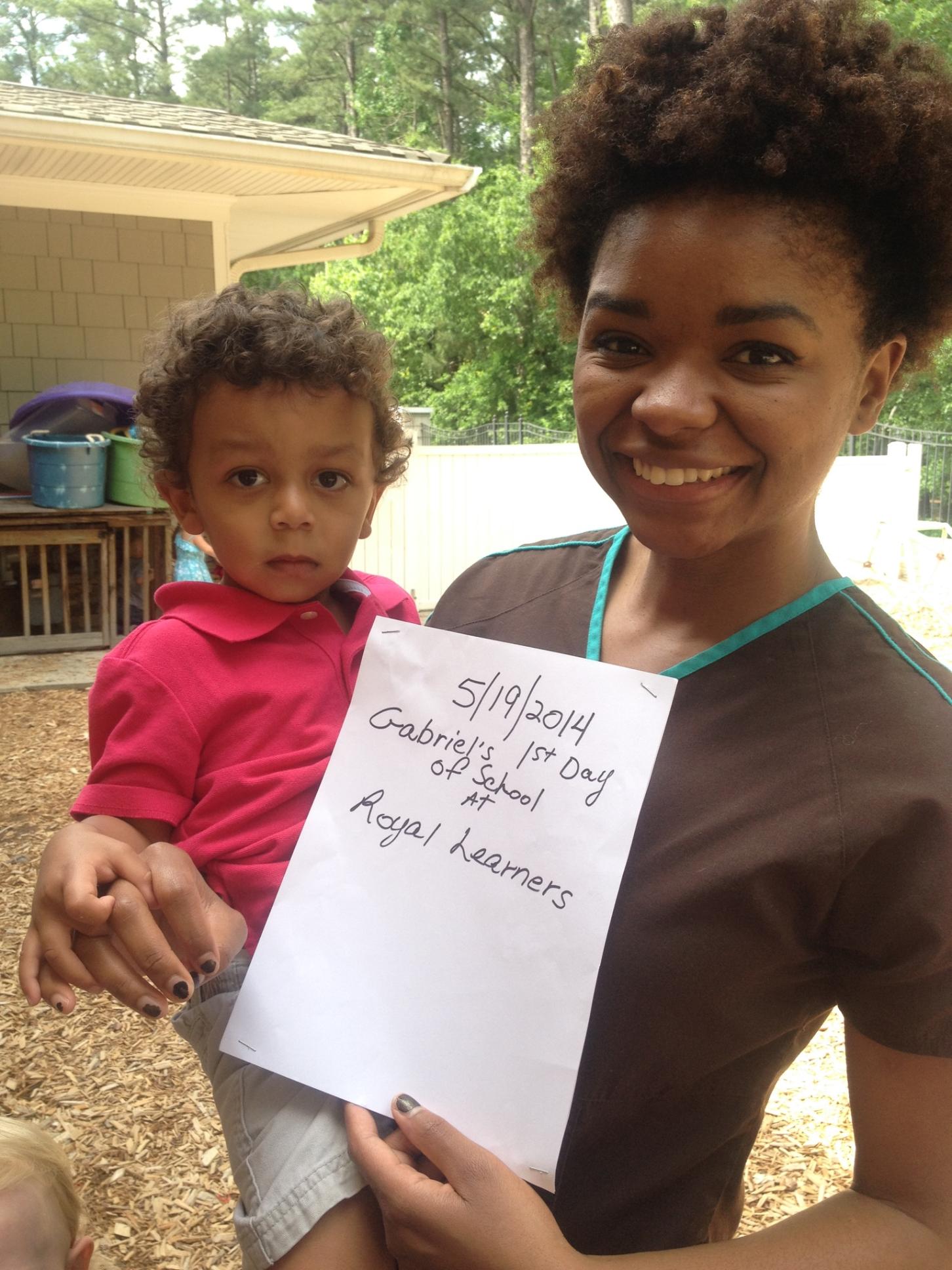

The GoFundMe was helpful. Find someone for childcare if you have children. Reach out to childcare facilities and say, “I have cancer, or my niece has cancer. Can you offer a reduced rate?”

And they did. They offered a reduced rate for my son to go to school. Because my 75-year-old mother couldn’t take care of him all day, we had him there till 5, and then she needed extra help at night. I would say those are the two biggest things. I was in the hospital, so meals at that time weren’t helpful, but if you’re home —

Esther, TPS: They might not have been that good, but they were meals.

Loriana: I didn’t eat it. I gave money to the nurses, who were also my heroes, to go. They would go to Whole Foods and other clean eating grocery stores to pick up groceries for me. Who expects to be hospitalized for an entire year?

»MORE: Tips on food and drinks to help during chemotherapy

There are many ways. You can have someone clean your house for you so you can spend more time with your loved ones. There’s so many ways that support can happen. Then support can happen even after. When you go into survivorship, you need a break, but you’re too broke.

Esther, TPS: So what do you do?

Loriana: I’m still working on that part.

Importance of Prehabilitation

Loriana: We are working at ArmorUp for LIFE. We’re working on creating some programs where I found those voids. I mentioned pit crews for patients. We’re also working on eventually creating some retreats, where we can create ambassadors.

You’re visualizing in the hospital that you’re going to get out, and you are going to get out. You are going to return to health, but in the process you have to prioritize your own well-being. If you don’t, you don’t want a secondary cancer. You don’t want to complicate the comorbidities that the chemo had.

I’m involved now in a lot of research at MD Anderson and the Mays Cancer Center, and there’s a lot of research looking at the stress and the connection to cancer. Then they’re breaking it down even deeper to the stress and connection to cancer or cancer recurrence for cancer survivors.

They’re getting patients and survivors into trials and having them doing therapeutic yoga and breathing and lowering their cortisol levels. They have a lower rate of recurrence of cancer, which is powerful.

One of the big things I advocate on is prehabilitation, prehab, preparing your body for illness.

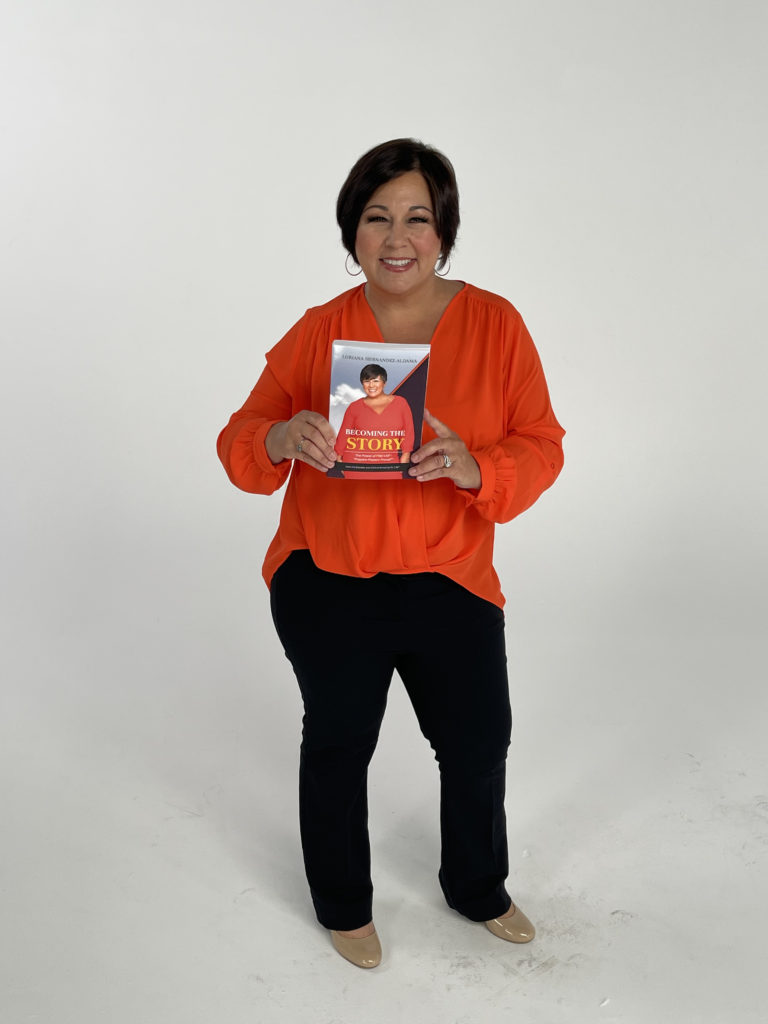

ArmorUp for LIFE

Esther, TPS: Talk to me about ArmorUp. This is ArmorUp. Tell us about ArmorUp for LIFE.

Loriana: ArmorUp for LIFE is my nonprofit that I launched from my bedside because I reported from my bedside during my journey, being a network medical reporter. I just said, “This story is bigger than me. I’m learning so much from these doctors that is not getting shared with patients.”

One of the biggest things I learned was that you have to prepare your body for illness. I said, “Why? How did I end up here as the clean-eating, green-drinking yoga enthusiast? They said, “Because guess what? Bad things can still happen to you. What sets you apart is how you showed up, and you showed up fit for this fight. Our hands are tied with so many patients here.”

They said, “The more fit you go into illness, the better you present to us as a medical team, the better your position to prevail.” I had 25% chance of survival, but they said, “Look, you have all 25. I have people on this hall who have 25% chance of survival or should, and they’re not fit enough to get the chemo [at the] same dose as you. Now they have 10 or 12.”

My message began saying, “Okay, we’re going to call this the 3 P protocol to be possible: prepare, present, prevail. You have to prepare your body for illness so you could present well to your medical team and position yourself to prevail.”

Preparing can start the day of diagnosis. It can start in the midst of your treatment. It can start well before you ever got diagnosed, if you have other people in your family and you know you have the genetic markers for it. It’s called prehab, prehabilitation.

Increasing Positive Outcomes

Esther, TPS: Being healthy is prehabilitation to begin with.

Loriana: Right. We’re prehabbing — you, me, Andrew, [and] everybody we know. We’re prehabbing every day with the decisions we make. When I learned that, that was like a really eureka moment that I have to get this message out. The more you go in, the better you present, the better your position to prevail.

That means your patient outcome, your chance of survival, goes up when you walk, when you stay mobile — mobility matters — [and] when you focus on risk reduction and lowering your stress levels. All of this plays a role in how well you go through treatment and your success rate.

Talking to patients, I would say it’s never too late to get started to start reducing your stress, even though you’re in the midst of turmoil. Let’s try to find time to meditate and take some deep breathing and lower your cortisol levels, because there are studies that show [stress] can cause a recurrence.

You don’t want to end up like me, where I’ve had 2 cancers. I’m always praying that there’s no third, that there’s another shoe going to drop. We have to really, in the midst of the chaos, still take care of our health and make decisions to eat right and exercise.

It can make a difference. Like they told me, you have all 25% chance because you’re getting exercise. You’re eating clean. You’re meditating. That is a huge component of your patient outcome and your success.

Esther, TPS: You’re stacking the deck, is really what you’re trying to do. Stack the deck so that should lightning strike, you’re not in the worst position. You’re in the best position to survive.

Self-Advocacy

Esther, TPS: You’ve really covered what propelled you to do as well as you have in your illness and your journey. I know, too, that you spend most of your time now being an advocate for other patients [and] raising their voice.

In this whole system of taking care of patients, who else has to hear this beside the patient? You can scream in an empty room, and nobody hears you. I know that the work you do is training patients.

There’s this other piece that I hear from patients all the time: “My doctor’s not listening to me. My medical team doesn’t get it. The pharmaceutical companies may or may not have the drug I need.” Can you talk a little bit about how a patient can navigate some of that to their advantage?

Loriana: Yes, you have to be your own advocate. There is a fourth unofficial P, and it’s called being a pain in the neck. You really have to be pushy, push for answers, and be your own hero and advocate when you’re asking what other voices need to hear this.

That’s why I go and talk to conferences. The pharma companies need to hear this. Your providers need to hear it. The nurses need to hear it. Everybody who’s involved in this whole ecosystem. That’s why I call it a pit crew so much with ArmorUp for LIFE, because we need a team invested in our success to successfully get us to the finish line.

That means that our provider needs to lean in and listen and ask questions like, “How do you have transportation to get to this clinical trial?” Or ask about your family history or ask about your comorbidities.

Like for me, I have baggage. When I was going through treatment for breast cancer, I tried to explain, “I’m a unicorn. I had leukemia, I had a transplant, and I don’t even have my own DNA. You need to talk to my leukemia doctor. You cannot operate in a silo. Call him up. Find out what is best.”

I felt like I had to be a reporter doing email intros. I said, “This is so much work. It should not be this hard to survive.” I say that the providers need to listen. They need to listen. I understand that they’re busy with charting, there’s a shortage, and they only have 15 minutes.

To the patient, bring in bullet points. Help get them the most information in those 15 minutes. To the provider, be aware of your implicit bias. I know that you need to ask the patient more questions than just, “How are you feeling?” or, “Your counts are good.”

It needs to go, “Do you have transportation? Do you have childcare? What’s getting in the way and keeping you from coming to this treatment that you need or keeping you from taking this drug?”

We have the providers. We have the pharmaceutical companies, and the pharmaceutical companies have a lot of patient support programs. They’re called PSPs. Who knew? I never knew about that. I told them at the conference I was just at. How would I have any idea that all this work exists? Nobody said.

I was on 40 drugs from probably so many different companies. To patients, if you are having trouble, there are programs that pharmaceutical companies have that you can say, “I’m on this particular company’s drug.” Call [them].

They may have a nurse navigator who could talk to you, but really we all need to come together, collaborate, and let each other know we’re here for you. It comes down to communication and knowing what’s available.

Esther, TPS: True that, and from some recent personal experience I’ve experienced. Being a care partner, not with my husband, but with my aging mother, where the system you’re talking about wasn’t listening.

It really was literally a 2×4 that had to be taken on by me and my siblings to get people to listen. I think people have to realize that our systems, especially in the U.S., are complex enough that unfortunately it falls to the patient and their pit crew to try to make those communications happen.

Second Opinions & Shared Decision-Making

Esther, TPS: I think you’re really right, Loriana, that there’s a lot of onus on the patient and their pit crew to do a lot of this. I think that a lot of people just aren’t prepared for that. [It’s] one more burden they have to take on to get the best care they need.

Loriana: It has to be shared decision-making. If you’re a patient and you’re listening, you can’t just say — I mean, you could be at the best institution or in a rural community. You can’t just take that one person’s answer as the Bible for you.

I would say get a second opinion even when you like the first. I loved my first opinion. They said I didn’t have cancer. But I still didn’t feel right, so I got another opinion. They said I didn’t have cancer. It took my fertility doctor to tell me I had AML leukemia. [After] the 2 doctors who misdiagnosed me, I said, “That’s it. I’m going to Johns Hopkins. They know what they’re doing there. They have to save my life.”

Esther, TPS: The additional opinions and being clear whether the person you’re talking to is really listening.

Loriana: Absolutely. Be very clear with your doctor what barriers you have in place: childcare, transportation, finances. Ask him or her what resources [are available]. Can they connect you to the patient navigator? If you’re not getting answers, keep going up the chain.

Ask the chain of command. Ask for the financial navigator. We’re starting to hear more navigators now. They’re taxed. They don’t have enough help, but keep asking and keep pushing. Eventually somebody is going to help you. Don’t just take one opinion and think that that is the best opinion for you.

Helping Underserved Communities

Esther, TPS: Let’s switch gears for a second. There’s a whole other area of the work that you do — and it’s part of who you are — as a Hispanic health advocate.

What do you see as the biggest challenges in meeting the needs of some of the underserved communities? Whether they’re Hispanic, black, or poor, rural white communities. It’s not just a matter of a minority. It’s really more the communities that aren’t getting what they need. What are the biggest challenges right now?

Loriana: Yes, there are so many communities who are underserved [and] who certainly need help. They get left out. So many times we hear at conferences about these high-level institutions. I kept saying, “If there were patient voids at the top, what’s happening in our rural communities when it’s one doctor, with not getting a second opinion, and that’s the only doctor you have access to?”

One of the biggest voids, I will say, in the Latino cancer community — I spoke at their conference earlier this year, and they’re expecting a 142% increase in cancer cases just among Latinos. This year among Latinos, they also say that the number-one killer for Latinos is cancer. Again, there are other startling statistics for other underserved communities. I just happen to know those off the top of my head.

One thing I say is we’re talking a lot about diversity in clinical trials, and that’s great. I’m glad that it is now a hashtag and a trend. But if we can’t get our communities, like my Latino community, to get into a screening because they don’t want to know, they’re in denial, for whatever reason they’re not going, and there’s trust issues, [then] they’re not even going to make it to a clinical trial.

»MORE: Learn more about the process of clinical trials from one program director

We need to not put all of our eggs in one basket about clinical trials, which are important, and having diversity and fitting more people in. [We need to] focus on the voids in the Latino community, the black community, the Asian community, the Indian community, the lesbian-gay community, [and] all these communities that have certain cultural competencies and different reasons that they don’t go into screenings because there’s trust issues. [We need to] focus on getting them into screenings and build trust at every point along the way in the journey. Then we have them here for the clinical trials.

Esther, TPS: Not treat the symptom; treat the cause.

Loriana: We are more than just our disease. Look at the whole ecosystem, the whole patient, who they are, where they come from, and why that’s a barrier. How do we get them into more screenings? We have to build trust. You can’t just come at them out of nowhere.

It’s just like, “Bam, here, want a clinical trial?” No. Where were you in my community? That’s why we’re hearing about some advocacy going on in churches and barbershops, where there is trust. That’s where I find all the voids.

First Steps for Advocacy

Esther, TPS: Let’s say one is a newly diagnosed patient or a survivor that is [reading] this. They say, “Okay, I want to raise my voice. I want to be involved in paying it forward.” How do they do that? Where do they start?

Loriana: The first, quickest thing you can do is start raising your voice by yourself through social media, because that’s something everybody has access to. I would start thinking of when you share your post, share not just what happened to you.

It doesn’t have to be an angry post. [It can be] something about what you went through and what the takeaways are. You can post that through social media just to share, like, “Hey, you should get this screening. Did you get your screening, did you get your mammogram, and did you get your colonoscopy?”

That can eventually grow, but then also reach out to organizations for areas that you’re passionate about. [Maybe] it’s prostate cancer or leukemia. Is it breast cancer, or is it overall just all cancers? Wherever you want to get involved and reach out and say, “I want to help in some way.”

Esther, TPS: They do that in the medical center, too. I would surmise that they have patient survivors that go and visit other patients to try to support them.

Loriana: There are so many ways to get involved. Again, the quickest and easiest way to get started, as it grows and as you reach out to others, is through social media.

Advice for Advocates

Esther, TPS: Listening to other people who are trying to figure out their path toward health, potentially for advocating for other people, and as they advocate for themselves, what advice would you give them?

Loriana: There is so much that I want to say right now.

Esther, TPS: I know you just gave a lot of advice.

Loriana: First, I do want to mention some things that we are launching, which are very important, because it is going to help people. In February, we’re launching a prehabilitation awareness month because it never existed. It’s so important. We’re calling it PREhabilitation Nation.

I talked about prehabbing. That prehabilitation that I mentioned is something we can all be doing. If we can help risk reduce, which is prehabilitation, in our underserved communities, they can present better and be better positioned to prevail.

That means maybe where you would not have qualified for intensive chemo, if you show up in a more fit state, maybe you can, which can change your outcome and help you survive cancer. That’s one big campaign that we’re working on.

I just encourage patients all the time that you have to get involved and ask questions. You just can’t take what the doctor says, he or she, no matter how brilliant they may be, as that’s the final say.

Even when I fly now to Johns Hopkins and see my oncologist who saved my life, once he says, “Your counts are good,” I want to skip out the door and sing “Zip-A-Dee-Doo-Dah” out the door. But I forget. Wait a minute. I have all these other problems.

Go in with notes, remember, and help connect the dots. Who do I need to see? If you’re a cancer patient, do you have a cardio oncologist? The chemo is going to impact your heart. You need a baseline. Do you have a dermatologist oncologist? If you’re a woman, do you have a GYN oncologist? Do you have an immunologist?

You have to start building your own pit crew. I say to patients, get empowered, ask questions, and even on a good day at the doctor’s office, ask more questions and find out who else you need to be connected to.

Esther, TPS: And bring a henchman if you need to.

Loriana: Yes, absolutely. During COVID, that was hard during the pandemic. Now, with Zoom especially, you can easily do that. If you could do telemedicine on a call, you can have somebody who might be more health literate than you.

Even if you’re health literate, when you’re in a time of crisis, you don’t remember everything. Once they give you some bad news, you don’t hear another word after that. You need somebody who can be there with you to take notes, to recap, [and] to ask if you can record the conversation. I just can’t stress enough that you have to be your own advocate. You can’t count on the system to do it all for you because they don’t have all the tools to do it.

Conclusion

Esther, TPS: Loriana, thank you so much for all of your energy and your insights. Your energy is amazing.

Loriana: I’m a little high-strung. Can you tell? I’m just happy to be here and be alive.

Esther, TPS: Not at all. It’s really inspirational, because what you said about preparing for a unique journey is really what it’s all about. It just takes a lot for somebody to go through it. You got to pull it all up from the inside. It’s hard work to survive.

Loriana: I say that as I struggle, and I’m very transparent about my depression and PTSD. Some days it’s so hard, and I have to remember that we all have purpose. For me [or] anybody who’s going through struggles, if you don’t feel like you have purpose, find advocacy, because that helps me with my depression.

I went from living the life to fighting for my life and so lost, wanting to take my own life because there were no tools and survivorship for me. My news director reached out to me, gave me purpose, and helped me get started.

If you give someone purpose, you feel like the world needs you. Even if you’re suffering [from] depression, you’re less likely to check out because you know the lives you can impact. So I’m glad. Esther, we need a whole big room. We need a stage. We need to take our show on the road.

Esther, TPS: Loriana Hernandez-Aldama, thank you so much for sharing your story with our Cancer Friends community. This is Esther Schorr, and wishing all of you the very best of health.