Telling Family About Cancer | Cancer Friends

Featuring Ruthie Schorr Menaker

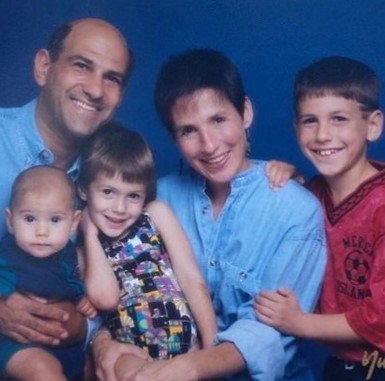

The Patient Story’s new series “Cancer Friends” features Andrew and Esther Schorr. They co-founded PatientPower.info, a resource for other cancer patients and caregivers to help them through their diagnosis and treatment.

This segment focuses on telling family and friends about cancer. Andrew and Esther are joined by their daughter, Ruthie Schorr Menaker. She shares what it was like growing up with the looming uncertainty of cancer. She also describes how open communication helped her family.

This interview has been edited for clarity. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider for treatment decisions.

It’s not the whole story of our lives. That’s not the only thing. You are not just a cancer patient. You’re my dad, and we’re facing cancer as a family.

Ruthie Schorr Menaker

Introduction

Andrew: I was diagnosed with chronic lymphocytic leukemia in 1996 and then a second blood cancer, myelofibrosis, in 2011. It’s been a long time. We are recording some segments for The Patient Story on coping and overcoming the uncertainty of living with a cancer diagnosis. In each segment, we’re talking about different issues. In this one, we want to talk about what comes up for people as you cope with the diagnosis. That is, who do you tell?

Esther: Before that, we need to say that we also recognize that it’s not just the patient who is coping with uncertainty. When there’s a cancer diagnosis, the family and people who love the patient are also uncertain about what the future holds.

Growing up with the uncertainty of cancer

Andrew: I’m sure Esther is going to talk about it, but we have the opportunity for 1 of our 3 children to join us. That is our 29-year-old daughter, Ruth Schorr Menaker, who joins us. Ruthie, thanks for being with us. When I was diagnosed in 1996 with chronic lymphocytic leukemia, you were 3 years old, so you have no recollection of that?

Ruthie: Nope.

Andrew: Okay. But time went on. What did you know about Daddy having a serious illness?

Ruthie: There was a period where real uncertainty was, kind of during a time where I wasn’t fully processing what was going on in the situation, so during your watch and wait period before you went to treatment. Then when you did, there were a lot of dynamics outside of you actually being sick that impacted my view on what was happening.

You were leaving to go to MD Anderson. Mom went with you. There was a lot of movement, and I think that’s when I started to kind of feel like something was going on. But I was pretty young at the time, so I don’t remember a lot of the granular details. I knew something was going on. As you continued to get treatment and other things, and you came back to Seattle and other things happened, it became more evident that this was going to be an ongoing part of our life and wasn’t for necessarily a finite amount of time.

Esther: Do you remember at all, Ruthie, there was a lot of uncertainty for the family and what was going to happen to Dad next. As you were growing up, do you remember what you were thinking about the impact on what might be happening for you and for your siblings?

Ruthie: I think the biggest thing was there had been things that were just not possible for us to do when Dad was going through treatment and when we were kind of adjusting to family life. I think in terms of uncertainty as a kid, the main kind of questions were:

- When is Dad going to be around to do this stuff?

- Is Dad going to be around to do this stuff?

- As I got older, after you were in clinical trials, I’m going to have my bat mitzvah. Is my dad going to be at my bat mitzvah?

- I’m going to go away to summer camp. Is something bad going to happen when I’m gone?

But I will say, I think part of it was impacted by the fact that I really grew up with it. It’s hard to think about memories [before] this happening, because I was just simply so young.

The taboo of talking about cancer

Andrew: Let me ask you about this. We lived on a place called Mercer Island, Washington, 22,000 people. Sort of everybody knows everybody. You went to elementary school, middle school, high school. You had a lot of friends who knew us, and maybe some of them knew your dad had cancer. Did it come up? The C-word is a scary word.

Ruthie: Because of the fact that it’s been so present in my life for so long, I think there’s kind of always been this edge to it that as much as cancer has been a taboo word or scary, it’s been ever present in our lives.

Since the time that you were diagnosed until now, I’ve sadly had many friends who’ve had parents, grandparents that have been sick, that have been lost. There’s a wide range of experiences that have happened to people, with cancer impacting their lives and their family. I almost think the fact that we all, you especially and me in conjunction in the discussions we had as a family, really made it less of a taboo topic to talk about with my friends.

I think everyone was very aware that it was happening, but the kind of conversations around it were, “My dad has cancer, but this is a chronic condition.” That was an adjustment in my mindset. Although I was feeling the uncertainty of it, I had just been living with it. By the time I was having these conversations, it was such an active part in my life.

Reacting to the second cancer diagnosis

Ruthie: Secondarily to that, when you were diagnosed with a secondary cancer, it was my first year away at college. I would say that experience in my young adulthood was much more rattling than what I remember of the early times of uncertainty in your cancer journey.

I was old enough to understand all the implications and uncertainty of that specific condition, which I knew nothing about, even though I knew all about the cancer that you had had at that point for 15 years. I was living far away, I didn’t really understand it quite as much, and I think that uncertainty at that point in time was much more startling, personally. That’s how I see it in terms of evolving.

Dealing with the diagnosis

Esther: Ruth, you said it was rattling. What did that look like for you? What helped you during that period? I’d hope it was communication with us, but what are the ways that you were dealing with that?

Ruthie: I think definitely the first kind of piece of it was that I always appreciated, especially at that point when I was a young adult, that we did just have an open line of communication about it. Dad, when you were first diagnosed, all of us had uncertainty because we weren’t super familiar with this specific condition.

But something that brought me some peace was that knowledge is the best medicine of all. I think that when you learn about something more, it becomes a little less startling. You say, “Okay, I can understand this mechanism. I can understand why this happens.” I think that I felt some peace, too.

Maybe it’s naïve, but I think the fact that you had been living with cancer for so many years beforehand, you had been in clinical trials, and you had tried new medicines and things — I had a lot of hope in modern medicine.

This was just, although unfortunate, another thing that we were just going to have to sort out. With open communication and support to each other. [We had to] just figure out what the next thing is. Maybe it’s another clinical trial. Maybe you have to go somewhere else for treatment.

My little logistical brain was kind of like, “This is how we can approach it, even though it’s upsetting.” There were a lot of pieces that I did have uncertainty about. We came at it as a family and as [pragmatically] as we possibly could. That made it a lot less scary.

Andrew: I’m so proud of you.

Esther: Very proud of you. What you just said about understanding it more and having some history, that medical science was working really well for Dad. [That’s] part of how I’ve coped with uncertainty, so I just want to say it’s not uncommon.

Talking to your family and friends about cancer

Andrew: We’ll talk more about that, but there’s a flip side, too. For people watching, not everybody’s been fortunate enough to be a long-term cancer survivor. Advocates are where there’s been a lot of progress. As we mentioned, we used to live on Mercer Island, just 22,000 people. Among your friends, you have a couple in particular where the parent died from cancer.

Ruthie: Correct. Yep.

Andrew: Given that it’s a — I don’t want to say a crapshoot, but there’s a lot of uncertainty about cancer, how your body will respond to treatment. Will there be treatments? Will there be clinical trials? What would you say to our viewers? If you have an opinion on whether it’s better to talk to your kids or some limited family members? What do you think?

Ruthie: I feel like you just spoke to the fact we grew up in an incredibly tight-knit community. The way that you’ve raised us in terms of where we live and the different social groups that we’ve run in, I personally feel as though being as open as you can be and you’re comfortable with so that you can have support around you.

With that is coupled not only for yourself and your family, for the people that you do tell, to ask them and implore them to have the education on it as well. I can’t think of anything scarier than having Sally Jo from down the road — you tell her that you’re going through something, and then she’s like, “Oh my God, are you going to die?” The question is, “I don’t know. I don’t know how this is all going to play out.”

But having someone in your ear saying that, [someone who] maybe doesn’t understand the situation or the complexities of it, can really sow a lot of fear. I think the other side of the spectrum of that is getting people in your corner who do deeply understand what’s going on and are as aware as you are comfortable with them being, so they can support you fully.

I’ve always felt like our approach of being that way — everything’s on the table — has been it. I just want to say to your point of whatever draw it is that someone ends up with a different or a more aggressive type of cancer. Of course, you don’t know that until you’re going through it or you’re in it.

But I remember very clearly being in my dorm freshman year when you called me to tell me that you had been diagnosed with MPN, and at that point, I didn’t know if it was like tomorrow that something was going to happen.

The battle after you understand what you’re going through is complex. I think the emotions, regardless of the level, are very real. It can be equally as upsetting no matter what it is, especially if you don’t have education on what that means or what it looks like.

Esther: It sounds like the open communication that we had as a family was helpful. Also, it sounds like you had relied on friends for support when you were away from home. Being open about it was helpful.

»MORE: Telling your friends and family

Being cancer advocates

Andrew: Now, we should acknowledge both Esther and I have been cancer patient advocates. Ruth went to Mercer Island High School. With the American Cancer Society, they had a cancer event around the track, [with] the kids camping out and raising money each year. Ruth did it, and I was the survivor speaker a couple of times. So everybody at the high school knew.

Ruthie: I don’t think that necessarily everyone’s perfect route to support is going to be putting it on billboards or a survivor on a poster board. I get that. Just my personal experience was being open.

Truly, one of the things that I had anxiety about was this idea that I talked to somebody new who has no idea about what my story is or whatever. “Oh, yeah, my dad, he’s a cancer patient,” I say. They say, “Oh my God, I’m so sorry.” It’s like, “I don’t need you to be sorry. I just appreciate the support. I appreciate it, but there’s nothing to be sorry about.”

I think kind of changing the narrative around, “This is something that happens to us.” It’s not the whole story of our lives. That’s not the only thing. You are not just a cancer patient. You’re my dad, and we’re facing cancer as a family. But it’s not the sole thing that matters.

»MORE: Read more of Ruth’s story on Patient Power

Has openness been helpful as a spouse caretaker?

Andrew [To Esther]: You have friends. You have parents, family members. The same openness, you think, has been a good thing?

Esther: Yes. Ruth addressed a lot of things that I’ve always felt — understanding as much about what was going on for you as a patient, what the conditions were, what were the options, staying really up to date in information — were helpful to me.

Right alongside that was the support of my close family and my very closest group of friends. I don’t want to say that I was fortunate that some of my best friends had also, in one way or another, been through a cancer journey. But partly that understanding of what was going on for you and for me as a couple and individuals was always very helpful. Just having the support of other people, other than a couple or the person that’s closest to a patient — it’s really important to have that communication.

Andrew: Well, we’re believers in it. You have to decide yourself what works for you, but it has worked for us. This is part of our series on overcoming and coping with the uncertainty of a cancer diagnosis. Look for other segments as well, where we discuss other important issues when you’re given this diagnosis of cancer. Thanks for watching and being a cancer friend. I’m Andrew Schorr.

Esther: I’m Esther Schorr.

Andrew: Thank you for watching. We like to say —

Knowledge can be the best medicine of all.

Andrew & Esther Schorr

Inspired by the Schorr family's story?

Share your story, too!