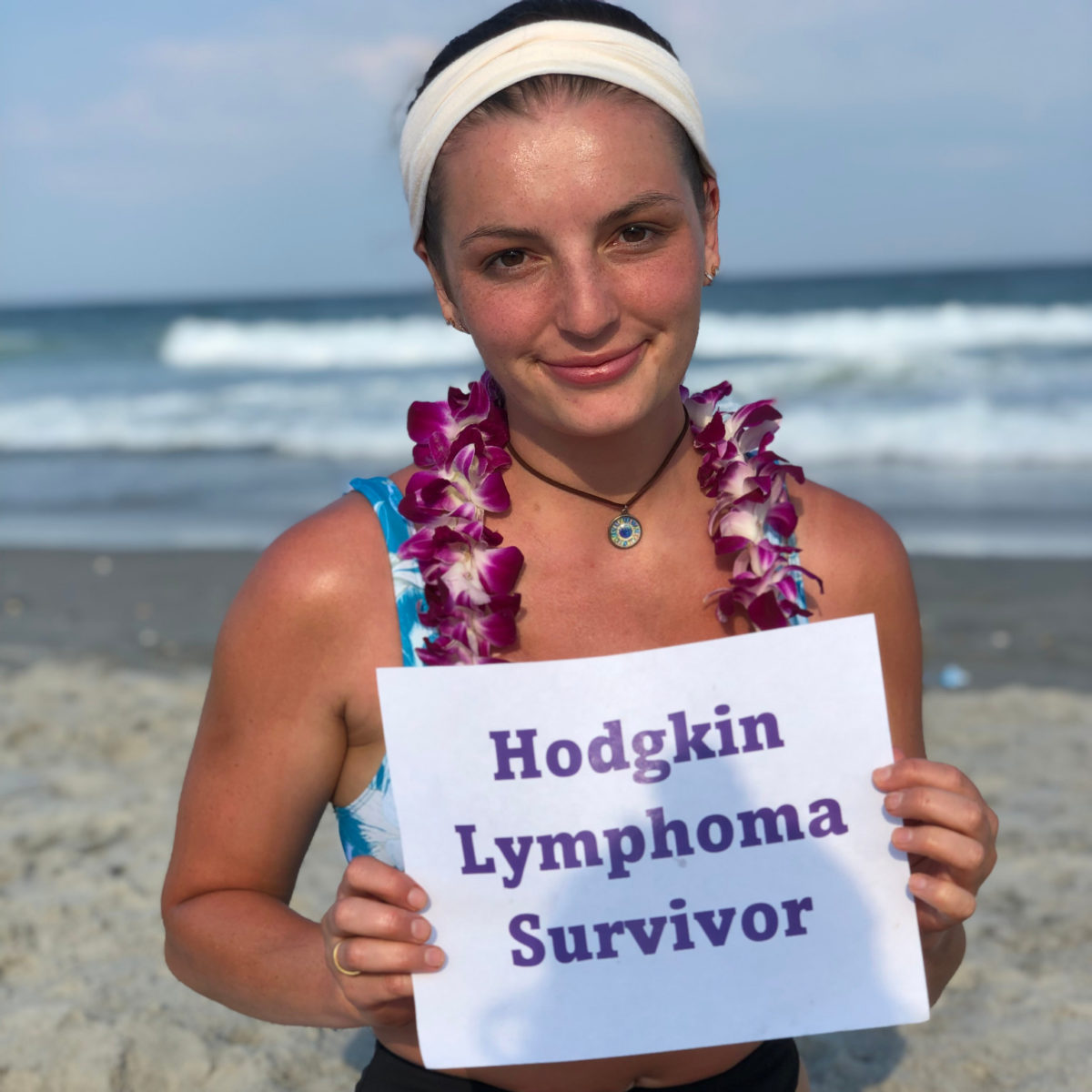

Ava’s Stage 4B Classical Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Story

Ava shares her in-depth stage 4B Hodgkin’s lymphoma story, from getting diagnosed to undergoing ABVD chemotherapy. Ava also highlights dealing with survivorship and finding a cancer community.

- Name: Ava O.

- Age when diagnosed: 21

- Diagnosis:

- Hodgkin’s lymphoma

- Stage 4B

- 1st Symptoms:

- Trouble digesting

- Weak immune system (always sick)

- Raised glands

- Night sweats

- Chest pain

- Extreme fatigue

- Extreme pain in shoulder blade and abdomen

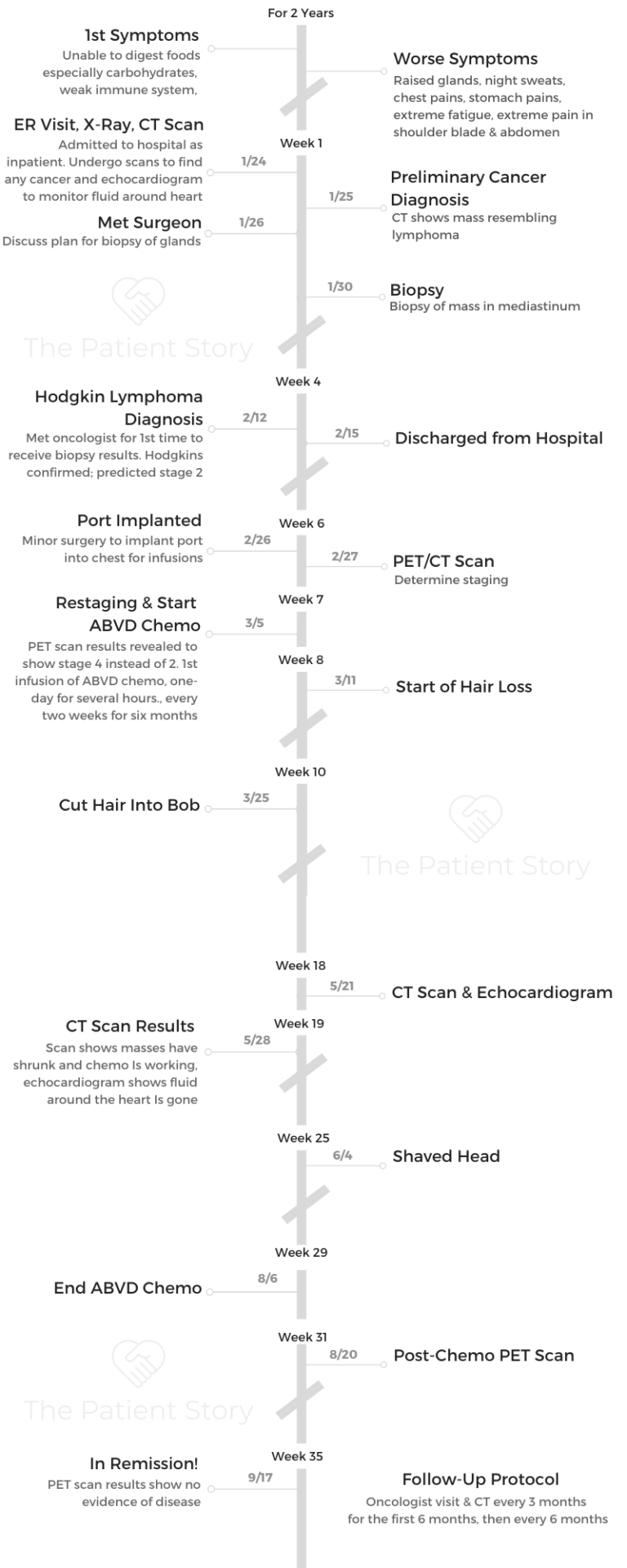

- Tests & Biopsies:

- Chest CT scan & X-ray

- Echocardiogram

- Biopsy of gland

- PET scans

- Blood work before every treatment

- Treatment:

- ABVD chemotherapy regimen

- 6 cycles

- Each cycle = 1 month, biweekly

- Total: 12 infusions

- 6 cycles

- ABVD chemotherapy regimen

- First Symptoms

- How old were you when you were diagnosed?

- How did you know something was wrong?

- Describe how the symptoms got worse

- It was tough to put all the symptoms together

- You discovered you had exhibited "rarer" lymphoma symptoms

- Noticing other behavior changes

- Doctors never suspected cancer

- Despite missing the cancer, you feel doctors did the best they could

- Cancer hid behind other medical issues

- Diagnosis

- Preparing for Treatment

- ABVD Chemotherapy

- Hair Loss After Chemo

- Scans and Treatment Progress

- Reflections

This interview has been edited for clarity. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider for treatment decisions.

Unfortunately, I think many cancer patients would agree that you tend to go to a ‘nothing place.’ You’re there, but you’re not there. Someone could tell you something, and you go, ‘Oh, okay,’ and nod your head.

Running took me there when I wanted to, and it helped me not taste chemicals. I would forget about the chemicals and how tired I was. It was just me and the road.

Ava O.

First Symptoms

How old were you when you were diagnosed?

I was diagnosed with Hodgkin lymphoma less than a month after my 21st birthday.

How did you know something was wrong?

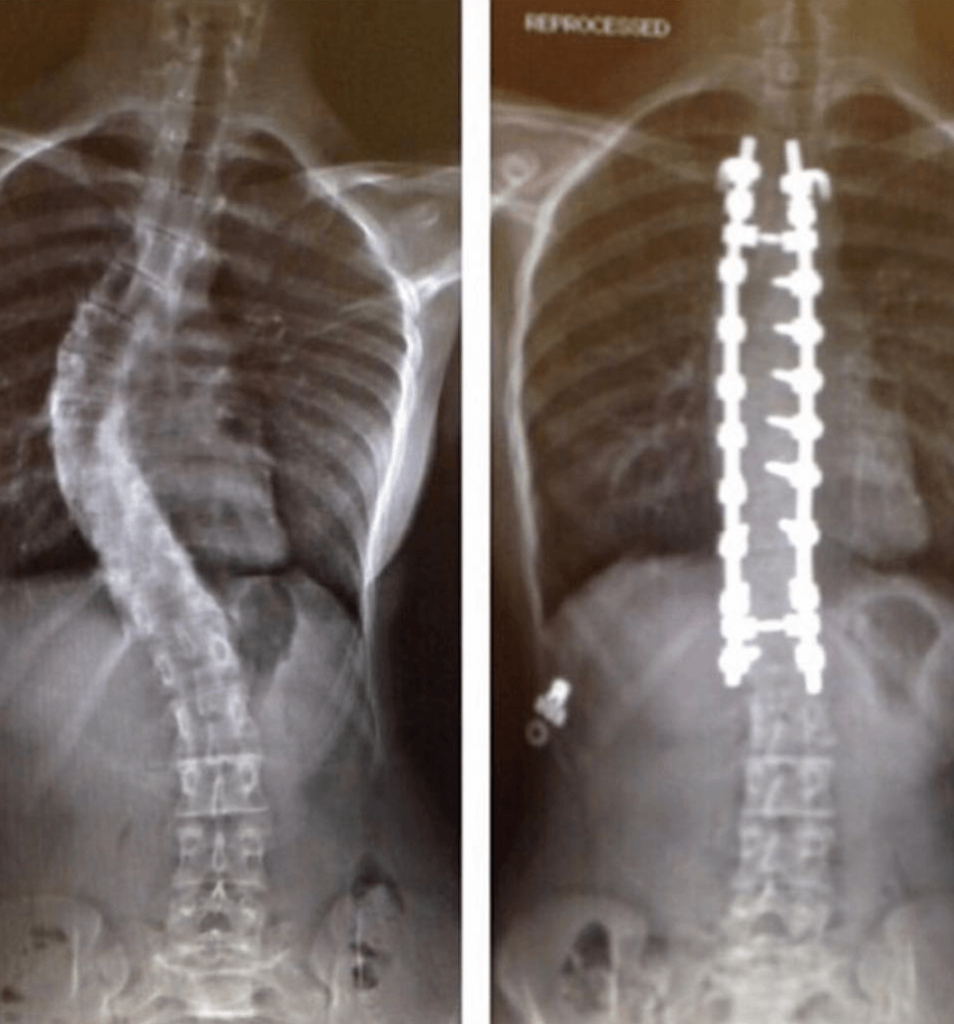

I knew something was wrong about a year and a half before I was diagnosed because I couldn’t digest carbohydrates properly without any given reason, and I was always getting sick. Other than undergoing corrective spine surgery when I was 15, my medical history was perfectly clean.

In January, I came down with something. It made me feel very weak, extremely nauseous, and I lost about 10 pounds during it. I had vertigo and coughed relentlessly for months.

At first, doctors in the ER questioned if I had something like whooping cough, but after several test results that showed that I was healthy, it appeared that I simply had a bad strain of the flu.

I totally lost my voice for about a month, and then after that, my voice would come and go. I noticed it would disappear when I drank alcohol or consumed foods containing lots of sugar and carbohydrates. I was rather athletic, but all of my muscles seemed to disappear at the same time.

To top it off, the amount that I was coughing actually led me to fracturing my ribs more than once. I missed so much class time because of how sick I was and ended up having to drop my classes halfway through my semester.

From that point onward, the coughing came and went, but never totally went away. I became more and more prone to catching colds very easily.

By mid-2017, I was constantly getting sick. Every time I recovered from a cold, I would catch another one, and again, the coughing lasted for months. As time passed, my glands under my jaw began to feel inflamed.

If my friends were sick, they knew to stay away from me because of how much a cold would actually impede my ability to function. My weight dropped by nearly 8 pounds and then slowly fluctuated back to normal. My body’s response to consuming sugar and carbohydrates became worse. They would made me feel drunk. I know that sounds totally crazy.

I tried to discredit that possibility so many times, but it is the truth. The day after consuming alcohol/sugar/carbs, including the healthy ones, I would feel hungover, and the glands under my jaw would be totally swollen.

Other than having a slightly abnormal white blood cell count, my medical tests showed that I was healthy, even though I didn’t feel healthy.

I saw a naturopath, who suggested we cut carbohydrates out of my diet and then reintroduce them later. I did what I could to maintain my quality of life, which meant trying it out. It wasn’t something I wanted to do since carbs are pretty important to your health, but my body wasn’t tolerating them. It was getting in the way of my ability to function.

In the end, I did what I had to do, thinking that everyone has something to deal with and that I was lucky that my health was still intact. It worked well, and my pains and discomfort diminished significantly until we tried to reintroduce the carbs. When we did, my body went into a frenzy of all of the symptoms I’ve mentioned, only they came back much worse.

All in all, my first symptoms were the swollen glands under my jaw, being unable to fully recover from a cold, facing adverse responses to alcohol and carbohydrates, and experiencing ongoing thrush/yeast infections.

Describe how the symptoms got worse

At the beginning of the next year, I felt my first raised gland in another area of my body: the inguinal area, which is below your pelvis. I mentioned it to my doctor, but it was believed not to be of significance, just as the glands under my jaw were believed a result of something harmless.

Then I faced excruciating pain in the left side of my chest that lasted for a couple of weeks. I couldn’t get out of bed without help.

It was thought to be a result of my scoliosis, although I had never felt shooting pain there before.

I experienced major stomach spasms in July 2018 that were inconclusive. Soon after, I faced an unforgiving nerve pain in my left shoulder blade, which was attributed to scoliosis.

The glands under my jaw were still deemed as harmless, and then they made an appearance near collar bones. Those largened over time. I also began to feel warmer than usual, and by August, I had night sweats.

I had been to see my doctor so many times, had a few trips to the ER, and underwent so many tests, all of which showed that I was still healthy. As time passed, the nerve pains in my left shoulder blade continued and spread to new areas of my body. My diet became more restrictive as my body’s ability to tolerate food decreased.

My strict diet continued, and changing it caused my body to go absolutely haywire. I was eating basic vegetables and getting nutrients from highly (healthy) fatty foods and protein to maintain my weight.

I was constantly calorie counting to make sure I was eating enough. I loved food, and I couldn’t eat even half of the food I loved. I was eating so much of the same foods, and I was eating constantly. I would eat a lot of avocados, almonds, chicken and eggs regularly as meals, and I also ate them in between meals.

Other normal foods (like potatoes, fruit, eggplant, toast, yogurt, carrots) would have the same effect on me as they did the year before, only worse. I would be flat on my back for weeks in pain.

My weight dropped again in December, and my muscle disappeared with it, without returning even as my weight restored itself. I was then forced to blend the basic foods I could eat if I were to eat without throwing up, enduring agonizing pain that was not diagnosed beyond IBS, or facing blood in my stool.

Between November 2018 and January 2019, I had been taken and wheeled to the ER 4 or 5 times because of how much unexplained pain I was in. I would plead to the doctors, begging them to believe that I had an extremely high pain tolerance and that I was truly in so much pain.

It was tough to put all the symptoms together

My key symptoms happened slowly and one at a time, almost making it appear as though they were all unrelated. My stomach pains, attributed to IBS (irritable bowel syndrome), occurred in the upper left quadrant of my abdomen, where the spleen is located.

Upon my diagnosis, I learned that having an enlarged spleen is a symptom of lymphoma, and it was causing my pain. The relentless nerve pain I experienced in my left shoulder blade, attributed to scoliosis, was parallel to the location of the mass growing in my chest.

Looking back, I was also actually quite itchy for some time, but I only realized that itchiness is a symptom of lymphoma much later.

There wasn’t one specific “classic” symptom that I identified with. I identified with many of them, as they occurred simultaneously. My downfall was a slow progression. It didn’t just happen in one day. It took many months and over a year for my symptoms to cause visible changes of concern.

You discovered you had exhibited “rarer” lymphoma symptoms

I couldn’t drink alcohol without the lymph nodes under my jaw becoming inflamed and painful. My doctor and I thought I was just sensitive to alcohol.

After my diagnosis, I learned that my body’s response was actually a rarer symptom of Hodgkin Lymphoma.

Noticing other behavior changes

I never nap, and I have never needed to nap to maintain functionality during the day, but in September (2018), I started to need to nap in order to have the energy to get things done. I went to sleep at 10 p.m., woke up at 8 am, and after having 10 hours to sleep, I still felt drained.

I began to think that being in pain was my new permanent normal. Coping was my new normal, well before my diagnosis actually happened.

Doctors never suspected cancer

They couldn’t find anything specific for a while (at the doctor’s office). It was masked behind IBS symptoms and residual scoliosis pains. Cancer exists at a cellular level before it manifests as masses.

The only medical test that showed signs of abnormality were my blood test results, which consistently showed that my white blood cell counts were slightly abnormal.

I started to take birth control in January 2018. At that time, my weight fluctuated up by about 8 pounds, but within a month of starting it, I lost all 12 pounds. I know when taking birth control, water weight increases. In my experience, the weight gained from birth control never dropped while I took it, so even if I lost some of the weight as my body learned to regulate on it, I likely shouldn’t have lost all of the weight. For the next several months, my weight fluctuated up and down by about 10 to 12 pounds.

During mid-2018, I felt so rundown, and the length of my list of symptoms extended since they started. When I explained all of my symptoms to my doctor, she recommended I take a depression test, acknowledging that my medical records showed that I faced a depressive episode several years earlier.

At the time, I was recovering from an 8-hour-long corrective spine surgery that involved implanting 2 foot-long rods into my spine and a double spinal fusion. The rods needed to be left alone to heal, and any physical jarring would have caused serious damage, so I had to stay home for months.

I was 15, and I couldn’t do anything I loved until I was fully recovered, which meant recovering for 2 years until I was 17. I endured a lot pain during that time, after all of the pain I endured before the surgery due to scoliosis. My depressive episode was the result of that.

Needless to say, I took the depression test, which I passed. I had never faced chronic depression, and overall, I had always been a happy person.

I felt totally undermined for being honest about how sick I was. I think her suggestion may have been more sensible if all of the physical symptoms I faced were not dismissed and a root cause was searched for until an answer was found.

I learned from my doctor’s response and approach to my yeast infections, which were not fully accounted for; my stomach pains, attributed to IBS; my worsening nerve pains, attributed to scoliosis; and my continuously fluctuating glands to believe that all of these symptoms were not to be concerned about beyond how they impeded my ability to carry out daily routines, to the point that I thought I was wasting ambulances when I needed them.

The only consistent sign that might have been telling were my consistently, slightly abnormal white blood cell counts. When one thing is consistently, slightly abnormal but everything else appears intact on paper, are you going to assume you have cancer? No. In fact, you’re told not to.

I had been seeing doctors all along since 2017. There didn’t seem to be a solution to all the pain that I felt under my jaw, in my stomach, in my chest and my back. That frustrated me. After several months spent tolerating such significant nerve pain, I finally could not bear it any longer.

My pain was the true catalyst behind why I ended up in the ER for the second time in less than 2 weeks on January 24th. It was the true reason behind my diagnosis. The ER doctors were concerned about the rods in my spine when I arrived.

Despite missing the cancer, you feel doctors did the best they could

You want to ensure that you’re being as fair as possible. My current GP met me when I was 18. Before then, I had a pediatrician who had known me all my life. Within a year of knowing my GP, my immune system was totally depleted, and I was getting sick all the time. In fairness, the Ava she saw at appointments was easily sick.

It didn’t seem abnormal for my white blood cell counts to be slightly raised considering how sick I’d get at different points. With that in mind, when you do the right things, you also have to take into account how long it occurs while you’re doing the right things and then figure out the reason behind why.

I go to a university in a different city than where my family lives. When I’d go to the ER when I was at university, I’d go to the ER there, and I would go to another one in Toronto when I was home.

Every doctor and nurse at St. Mary’s Hospital and Grand River Hospital in Waterloo was absolutely stellar. They were amazing doctors. Even without reason, since at different points in time nothing presented in my scans, they always looked deeper.

I don’t know how my scan from December 2018 led me to inconclusive results, and yet, within less than a month, the scan taken in January showed a mass in my chest.

Cancer hid behind other medical issues

Cancer hid behind an immune system that was perceived as weak, as well as symptoms that were chalked up as relating to IBS and scoliosis.

I also underwent spine surgery when I was 15 in 2013. Every now and again I go through nerve pain spams, which last for about a week. I’m talking about it in this interview as if it’s nothing, but I have just become so used to coping with the pain.

With that said, nerve pain is one of the top 3 most painful kind of pains that exists. When it’s there, there is no relief. It does not come in waves. It simply feels like your body is being pressed to a burning stove plate constantly. It’s just always there.

When this pain didn’t change after a week and then worsened for several other weeks and months, it was just a matter of time until breathing through it became useless.

Coping with pain was not new to me, and I was very good at it, but we all have a limit.

For me, it took years of unexplained symptoms, 6 months of constantly evolving pain, and 3 months of going to the gym to help my condition while it felt like my body was on fire until I couldn’t bear it anymore.

Diagnosis

What finally led to the discovery of cancer?

My back was in immense nerve pain that pain didn’t go away after a week, as it should have. It was present for months, worsened, and spread across my abdomen and down into my fingertips as time passed.

I was taken to the ER by ambulance in December a couple of times. On one occasion, I was huddled in a ball on the floor in my apartment in Waterloo.

I called my friend, who was about to hop on a bus to Toronto, at 7 a.m., sobbing because of the pain that rippled through my abdomen. He rushed over immediately and called 911. I remember crawling from my bedroom floor to the living room floor to unlock the door for him, remembering this pain from when I felt it back in July of 2018.

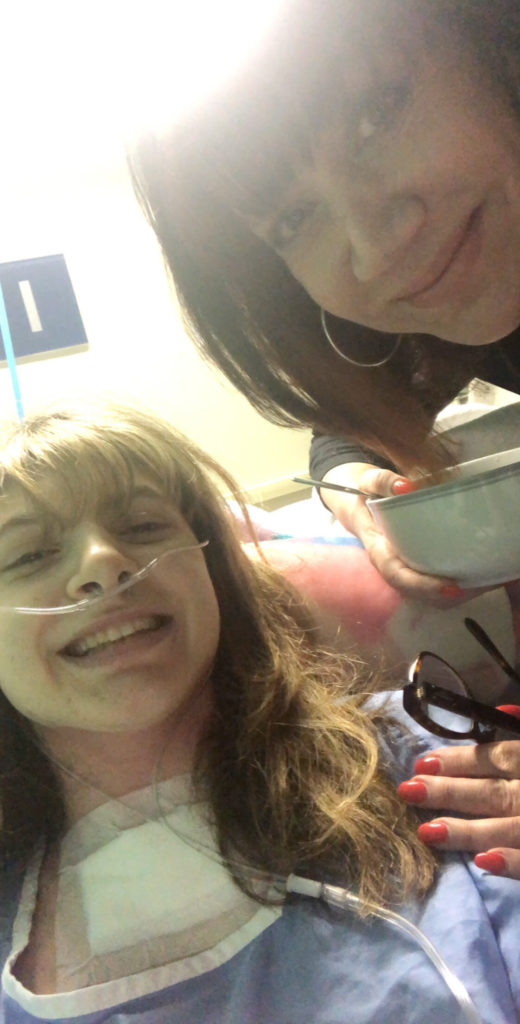

The other time I landed in the ER was when I was in Toronto. I was in the kitchen, and the nerve pain in my back was just relentless. I got on the floor in my kitchen and yelled for my mom. I was just lying there, screaming in pain.

I was a total mess, and my mom was just beside herself because she’d seen me in so much inconclusive pain for such a long. Every medical test had shown that I was perfectly healthy, and it just did not add up.

Both times I was in the ER that month, the doctors at both hospitals ordered scans, which both appeared as normal. The doctors administered morphine in an IV drip to relieve my pain (it didn’t work) and then sent me home.

On the day I was wheeled to the ER and later diagnosed, that severe nerve pain was still 100% present. The idea of breathing through the pain and talking yourself through it, saying to yourself, “It’ll be okay,” totally disappeared. I was at a point where that ability didn’t exist anymore.

Screaming in pain wasn’t embarrassing anymore. I just wanted it to stop. I begged and begged for an end to that pain. At that time, you could not touch my back in the area where I experience nerve pain because of how much pain it caused. It felt like stabbing to the touch. The ambulance paramedics had me hooked up to a morphine drip by the time I got to the hospital. It did nothing to relieve my pain, and I was in agony.

As soon as I arrived, doctors ordered several tests, but they had to try to get my pain under control so I could lie still for them. Doctors and nurses resorted to injecting fentanyl directly into my arms and legs to relieve my pain, and yet it was still ever-present. I just remember screaming, sobbing and begging for help.

I remember it as clear as day. The doctors and nurses said they had never seen anything like it before. Essentially, the meds calmed my body down, but it still felt like I was burning alive from the inside out.

They did their best to work quickly, and I did my best to lie still during my first X-ray scan. Then I had a few CT scans, an MRI. I was in the ER area for a while until I was told that I was being admitted.

The next morning, I woke up to a doctor’s voice. That was the turning point, marking the minutes when I went from being a 21-year-old girl to a 21-year-old patient.

The pain I endured had nothing to do with my previous spine surgery or IBS, and this time, the scans that were taken of my body did not come back clear. My health was not intact.

How did the doctor give the diagnosis?

She asked me, “Do you understand why you were been admitted?”

I remember saying, “Probably because I’m in so much pain that pushing fentanyl through my system has me loopy as hell, looking at you like you have 3 heads, and yet is not relieving my pain, but is making me tired enough to be still.”

I really did see 3 of her, and I really was still in so much pain. The medicine made me too drowsy to scream in pain, but it was there. Then she asked, “Where are your parents?”

I said, “They live in Toronto. I told them not to come up until today because every time I go to the hospital, I’m told I’m fine. I didn’t want to worry them at night over nothing. They’re on their way now. It’s actually comforting to know that this time, I wasn’t sent home.”

Then she said something that changed my demeanor. “It is best if we continue this conversation when your parents are here. I highly recommend that we wait until they arrive.”

I decided I didn’t want to wait if someone finally had an answer for me, so I called my parents and tapped speakerphone.

The doctor remarked that my X-ray scans showed what they called fullness in my chest, which led them to order a CT scan.

That showed a mass in my chest, resembling lymphoma. ‘Okay. What’s that?’ I asked.

She explained that lymphoma is a form of blood cancer. I actually remember feeling relieved to hear that. That sounds so absolutely strange, but I had been through so much trauma relating to my health for nearly 2 years.

By that point, I was very relieved to know it wasn’t in my head and there was finally an answer to all of my symptoms.

I remember saying, “Can we just talk about that after the pain goes away?” My parents were on the phone, and I was in the hospital, still so consumed by the pain that I didn’t even care that I had just been informally diagnosed with cancer.

On the other hand, I can’t even imagine being a parent on the receiving end of that phone call.

What were the next steps after the lymphoma diagnosis?

The doctor explained that I would have to undergo a few more scans and that the mass in my chest needed to be biopsied.

It would confirm my diagnosis. From that point onward, I would meet my oncologist.

Getting re-staged to stage 4B Hodgkin’s lymphoma

The biopsy showed it was Hodgkin’s. When I met my oncologist in early February while I was still in the hospital, I was told that based on the CT scans and results of other tests performed, it appeared that I had stage 2B Hodgkin lymphoma. She sent me for a PET scan to confirm the staging.

When I was told it was stage 2, I remember thinking to myself, ‘There’s no way it’s not stage 4, not with the symptoms I have faced.’

I looked at my doctor and said, ‘Keep looking.’

We learned the results of my PET scan at my first treatment, which was when I saw my oncologist next. She went through all the details and said that my treatment plans changed slightly because my cancer was stage 4 cancer.

I remember thinking in my head, “Thank you for finding it.” I knew there was more than what met the eye. In fact, I knew it in 2017.

How did they describe the B part of the diagnosis?

For lymphoma, there’s a standard type and a B type, which is referred to as including unfavorable symptoms. That’s when you experience things like weight loss, 10% or more in 6 months, night sweats that are ongoing. That’s what sums up the B component of lymphoma.

How did it feel to finally have an answer?

It was a major relief to me at that time. With that said, I hadn’t actually processed what was going to happen next, so I was just glad to know that all my symptoms came with a reason, beyond what was being chalked up as IBS, scoliosis and psychological.

Preparing for Treatment

What do you remember from the biopsy?

A biopsy is when they make a tiny incision (that’s how mine was), and they take out a little piece of the mass that exists. For some people, they take out a lymph node and send it for pathology. That’s how they find out if it’s cancerous.

Describe the PET Scan

You go in, and they inject a dye with sugar in it. Essentially, the tumors that are inside of you will suck up that sugar. On the scan, it shows up. The machine looks similar to a CT scan. You go in, and similar to any other scan, you’re lying still for the duration of it.

I can’t tell you how long it was. I try not to remember that part so much with most of the tests. I truly can’t say I remember much about lying in the room for the PET scan. It wasn’t really relevant to me. It didn’t bother me. I just remember how it works.

How did your oncologist describe the treatment plan?

Chemotherapy treatments for 6 months, ABVD chemotherapy. I know for different staging, they do radiation therapy. For me, they didn’t consider that.

How did you break the news to your loved ones?

My parents found out during our phone call while I was in the hospital with an ER doctor, who delivered the news over that call. I told my closest friends over the course of the next several days, while I was in the hospital.

When you are ill and you have to deliver the news about it to those whom you love, you already know the pained responses that it will elicit. The common idea to look for solutions and ways to alleviate that pain only leads to a “no exit” road sign; you know that nothing in your power will fix it.

Delivering heartbreaking news to the people you love comes with knowing that the news is going to hurt them and that there is nothing you can do to relieve the pain that it inflicts.

It can feel like you are causing pain. It is important to try to remember you’re not. Sometimes you feel like you have to console the people around you, and you do. I know that exists for many cancer patients, because there’s nothing they can do to fix the problem.

What people really want to do is fix the problem. The truth is you can’t. You can just be honest.

»MORE: Breaking the news of a diagnosis to loved ones

How did you allow yourself to be supported?

I found it difficult to let myself be supported. I wanted to continue to be as independent as I had been. I was the person other people seemed to turn to.

It took a lot effort and consistency for several years, but I had my life together. I liked who I was. I often pushed the people I loved away from me during what felt to me like my weakness, because I didn’t want to disappoint them.

I knew that my weakness would be a place for some people to project their lives and insecurities. The idea of being undermined because I couldn’t be the friend I had always been, and because I finally cracked and couldn’t be the girl who had it together as I battled cancer, turned my stomach in knots.

The worst part was that it came when I was already beating myself up for what I couldn’t be during those months.

In the end, here’s the deal: if you have people around you who want to be present with you and care for you, let them.

If they undermine you later, they weren’t your friends to begin with. You’ll learn who they are very quickly in silence. Don’t assume everyone else around you is like that, or else you’ll isolate yourself from everything good.

I did that to myself during the 6 months I faced treatment. I was around people, but I didn’t let them in. Running was the only support I accepted, not wanting to be a burden on anyone else.

Looking back, I am pretty sure not taking for the first while added the burden that others felt. One of the biggest lessons you’ll learn from those who stick around through your worst, during the treatments and the several months which follow after them, is how to take.

If you are a giver, you know how to give. But to take, you have to trust the people who are giving to you. When you are battling cancer, you have this opportunity to learn to take, and also to learn who wants to give unconditionally. You learn who you are and who others are very quickly.

The only thing that the people who love you can do for you when they know they can’t fix cancer is show up and be there with you. You may feel like you can do it on your own, and maybe you can, but that’s not the point. Let them be with you.

Let people who care be there for you, because that is their ability to show you how much they love you, and it counts for them, too.

It takes a village of family and friends who love and support you — and strangers who have no idea who you are but inspire you from afar — to get through it.

Don’t try to brush past it. Allow it to sink in for other people, too. You go through your own grieving process, and more often than not, you start coping from the get-go.

Coping through a diagnosis and then a cancer battle feels similar to coping with a high-stress emotional event the night before a major exam. If you have an exam tomorrow and something hits the fan tonight, you’re going to tell yourself, “Okay, this just happened, but I need to be prepared for my exam so I can succeed, so I’m going to deal with this after the exam.”

Except when you’re coping with cancer, your exam isn’t a few hours long. It is 4, 6, 8 or many more months long, so you’re just coping all the way through it.

All of a sudden, when treatment finishes — if it does — you’re lucky enough to be left with the emotional burden from 4, 6, 8 or more months ago, which was suppressed during that time to simply get through it. It is a mean feat to face.

If there’s a bright side that exists, it is in our ability to learn how to take the pure care and deep love that others are so willing to give to us during the most difficult times in our lives.

It’s difficult because you have a sense of who you are and who you’ve always been. You can do what you want because you can, but when you’ve just been diagnosed or just started your treatments, you haven’t quite realized that in just a few months you might not be able to be the person who you have always known yourself as and who you have always been.

If you can grieve and come to accept that loss before you reach that boiling point, you’re remarkable. I couldn’t, and the pain weighed on me every day. Yet everybody is still in your camp.

Letting others support you during your greatest vulnerability should lead you to feel a sense of pride. You are special enough to those people that they want to be there through your worst.

Did you have PICC line or port?

I had a port implanted while I was in the hospital. That was a fascinating experience. If you have a doctor who allows you to watch, definitely do it. Best experience ever.

I had my Grey’s Anatomy moment! Everything is upside down, and you don’t know what’s going to happen, so why not?

Describe getting the port inserted

I wasn’t asleep, but that was my choice. They offer and typically recommend you take that. If you ask, they’d probably knock you out if you’re uncomfortable with the idea.

That was me when getting it removed. I didn’t want anyone touching me. I didn’t want to be awake.

It’s really not terrible at all. You are awake. You’re kind of drowsy, from what I’ve heard from people who were sedated for it. You feel some pressure, but you don’t feel pain.

I think the whole thing takes half an hour, which is pretty fast. Of all of the things people go through during cancer battles, that’s likely the easiest part.

The port is almond-sized, placed under the skin, and attached to the vein. After the procedure, you’re left with 2 scars, one of which will become almost invisible after it heals.

You’ll feel a slight bulge where the tube of the port is located in your vein. It feels like a skinny straw. After the chemotherapy is pushed through your port, it flows through that tube and into your veins. That’s how it accesses your system.

Did you like your port?

I liked it when I didn’t bump into anything! Bumping into your port feels like stubbing your toe or hitting your funny bone. Every time it happens, you’re thinking “Oh no! Not again!” You know that you’re going to feel it for a little while.

I’ve never had a PICC line, but I do know they flow through your arm. My friend had one, and I know it was rather inconvenient for him. When he had his taken out, he was excited to shower with his arm finally free from the PICC line.

On the basis of knowing that, I’d say it was a privilege to have a port. If I didn’t know that, I wouldn’t have an any idea about what having a PICC line was like.

»MORE: Read patient PICC line experiences

ABVD Chemotherapy

Describe how long the infusions were and what they were like

I underwent ABVD chemotherapy treatments every other Tuesday of the month for 6 months. On the good days, the infusions lasted three to three and a half hours. On the bad days, they lasted 4 hours.

However, my treatment center was out of town. Prior to treatment infusions, the doctors needed to see my blood test results, so I was typically at the hospital for 5 or 6 hours.

After I was diagnosed with cancer, I forfeited my semester at university and moved back to my family home in Toronto. I had the option to be treated at the cancer center closest to me in Toronto, which is Princess Margaret Hospital.

I chose to continue my medical treatments where I was diagnosed, in Waterloo, which was an hour or so away. Grand River Hospital’s Regional Cancer Centre followed the same protocol as the cancer center at home, and the medical staffing at Grand River Hospital was incredible.

Essentially, instead of driving to Waterloo for the blood tests, coming home to Toronto, then going back on another day for my treatment, we did it all in one day.

My parents and I usually left Toronto at 6:45 a.m. and arrived in Waterloo around 8 a.m. I had my blood taken around 9 a.m. We usually waited a couple of hours for the results before the infusion process began, and my treatment typically started around 11 a.m. or 12 p.m. I would be there until around 3 p.m., or 4 p.m. on a bad day.

I’d finish treatments and usually go directly to the gym for a run and a workout. That would be it for the next 2 weeks. Then I’d go back, and we would do it all over again.

For me, undergoing treatments in my university town, Waterloo, allowed me to see my friends before, during, and after my treatments, which helped me feel normal.

After my treatments, I would go to the school gym for a workout and see all of these people who I always saw in the gym. They had no idea I was sick. I just felt normal.

I was really fortunate that my parents were able to make the drive every other week in spite of their jobs. It took a lot of effort, but it made a huge difference for me.

»MORE: Read our comprehensive ABVD chemotherapy info page

What were the ABVD side effects, and when did they hit you?

Summary: fatigue, weird tastes (chemicals), bloating, weight gain, hair loss

Fatigue, first of all. By the time you’re finished, I was exhausted. They gave me doses of Benadryl because one of the drugs could cause allergic reactions in the body. They would give me Benadryl and then give me a steroid.

The funny part of this is the Benadryl is conking you out, and the steroid is making your body go, “Zing!” You’re an odd combination of wide awake and very sleepy at the same time. In the middle of treatment, the fatigue right after set in.

I tasted the chemicals. I hear different things about that. They did not go away. I tasted that for the entire duration of the 6 months, and even a little while longer.

That set in within the first few days of my first treatment. I tasted while they were pushing the chemicals through, and it lingered after that.

Significant bloating, some weight gain. I think it’s something so undertalked about. People talk about losing weight because of treatment, but in this one, it’s not the case.

With the steroids, you’re going to have moon face for a while. You’ll just have to learn to love moon face. Steroids definitely make you gain weight.

It’s difficult because the way you gain weight, you don’t look like you. When people normally gain weight, it’s a progressive weight gain, and you see slow changes. You can gain 3 pounds on this, and your face is going to look like you gained 25 pounds.

How did you deal with the ABVD chemo side effects?

Summary: exercise (running), drinking a lot of water

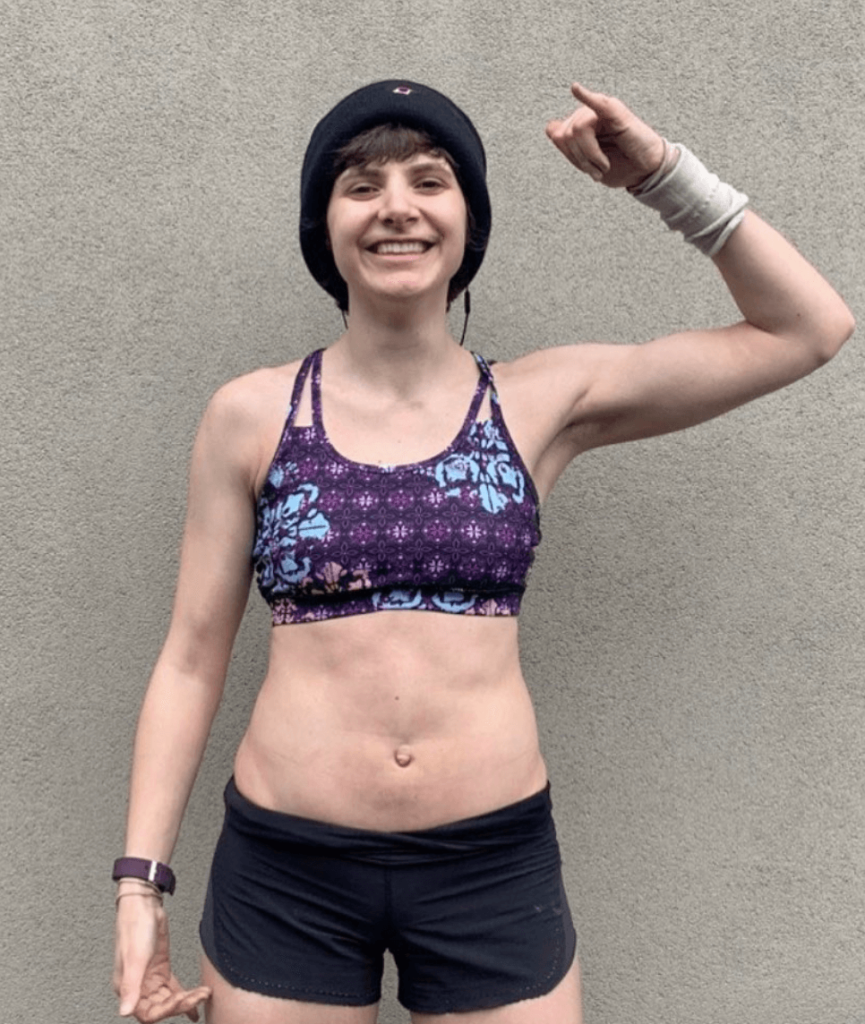

The fatigue is key. I used to force myself to go for runs after chemo and to the gym after chemo. I can say that is the most trying thing I’ve ever done in my life. I’d go from chemo to running 3 or 4 kilometers, and then do a leg day right after.

For me, I had the okay from my doctor that I could. That was just a way to grasp some control of my life. I knew I wasn’t really going to enjoy it, but I’d rather be on my own terms.

I’d done everything right, so I wasn’t about to let go of that. People hold on to different things. I held on to my health and all the things I’d ever done for my health.

Drinking 2 liters of water every day was one of the toughest things I did. Every morning, I’d chug 16 ounces, and that was the start of my day. I made it a rule that I couldn’t do anything else unless I did that.

I kept running in there, which worked in my favor, too. I tricked myself into thinking I couldn’t run unless I drank those 16 ounces of water. I’d get these 2 liters of water in, 64 ounces total, every day by forcing myself to do it, essentially. It was to keep myself healthy.

When your body is absolutely exhausted, your body’s ability to stand up straight without slouching is not very present. My body was twisting and doing different things, and that was one thing that was helpful. It was my grip on reality.

Running was also to boost your mental health

Running also helped me faced grief. Unfortunately, I think a lot of cancer patients can agree that you tend to go to a ‘nothing place.’

It’s called survival mode. It’s like you’re there, but you’re not there. Someone could tell you something, and you go, “Oh, okay,” and nod your head.

Running took me there when I wanted to go there, and it would help me not taste chemicals. I would forget about the chemicals and how tired I was. It was just me and the road.

Chemo brain

The key for me was chemo. I don’t know what it did, but it altered the way I thought, the way I lived, what I did, how I perceive the world around me, everything. It was to the point where I couldn’t think. I couldn’t think at all.

That wasn’t cancer. That was chemo, because I had known I had cancer for 2 months before that. Even when I was drugged on Fentanyl, I wasn’t like that. This was something that started happening in May after I’d been on treatment for 2 months. I couldn’t think of things. I still have trouble finding words to this day.

I say things like “umm” because I’m trying to think of things, and that never used to be a thing for me. I’ve tripped over my own words (in this interview). It’s just my reality right now.

Hair Loss After Chemo

Describe your hair loss

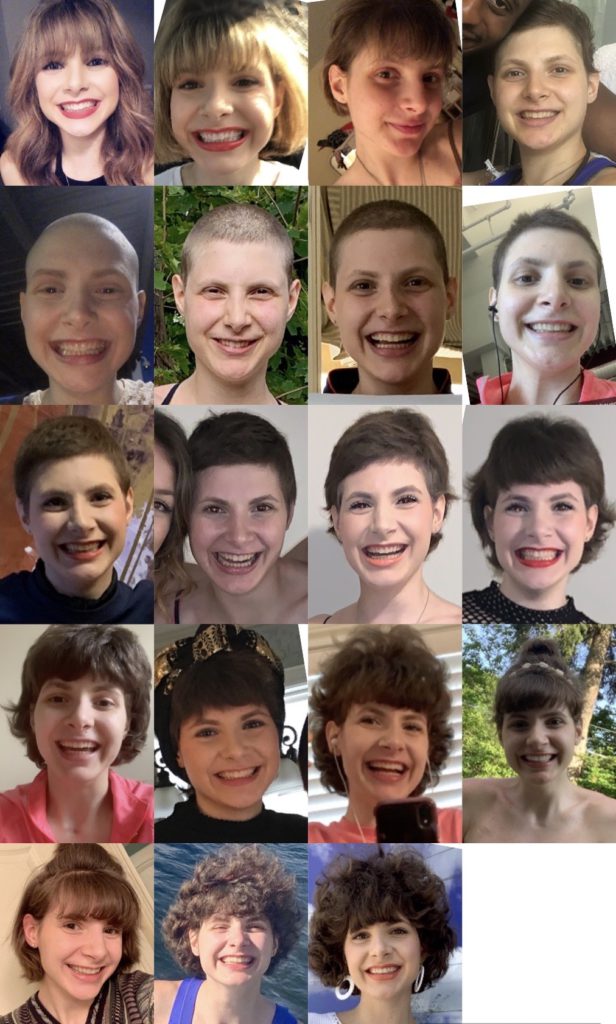

I started losing my hair within the first 2 weeks of my treatments. Before my third treatment, I chopped it all off, so I had a little bob. I had long blonde hair (my hair’s not blonde anymore), but I chopped it off because I was tired of watching it fall everywhere. My hair was extremely thin and falling apart by May 31st.

I had really thick hair before, so the amounts that were coming out were obscene. I also made some jokes at one point and made a mustache of my hair on my mouth.

I’d gotten one of my friend’s hats, and he was like, “I have lice!” It was a joke. I said, “It’s fine, my hair’s going to fall out anyway! Lice aren’t living very long there, anyway. Let them enjoy!”

The transition from bob to shorter hair to shaving your head

I put it into a bob. That was within the first month of starting chemo. I tried to keep my hair as long as I could. Even before I started treatments, [I had said] I’m going to keep it for as long as I can.

Then in July, I was finished with it. I cut my hair into a bob, then I cut it a little shorter a few months later, and then a little shorter, and a little shorter.

I still had my hair, but it didn’t look like my hair. At one point, I didn’t want to look at it anymore. I could see it still falling out, and it didn’t look like me.

People who shave their heads off the bat are brave. I know that also is an aspect of control for some people.

But I didn’t want to do that. I still think that’s extremely brave to take it into your own hands before it’s taken away from you. That’s really difficult. You have to live with the fact you chose to do that, That’s how I feel about that, thinking it’s extremely brave.

By the time I shaved my head, I already felt so much not like myself that it didn’t even matter at that point. I was like, ‘I don’t look like me anyway, so what’s the point?’

Mental and emotional impact of hair loss

Hair loss is definitely super difficult. You don’t realize how much it is part of your identity. When you’re losing your hair and gaining your weight at the same time, I think it’s one of the most difficult parts of it.

There’s not much you can do about it, because you’re just going to go through and be coping with it.

Using humor to deal with the pain

You have to make obscene jokes because if you’re not laughing, you’re crying. You’re doing enough of that as it is.

Make a decision good for you

A lot of people, even the people you love, are going to have an opinion, and that’s fine. The difficult part about that is everyone is going to want to understand. The people you love want to understand, but you don’t even understand because all you’re doing is coping.

I needed time, and I was not able to explain the reason I was doing different things at that time until much later. Your family, even if they ask questions, will support you. They’re also just wondering, “Why now?” That’s a normal question, though it doesn’t feel normal at that time.

The way I felt about the whole thing was, ‘Okay, this is going to be what I go through, and I’ll see how everything happens. I know who I am, and I like who I am, so whatever has to happen to my face and body, that’s fine.’

Scans and Treatment Progress

How was your mid-treatment scan?

The middle scan was great for what it was meant to be. It was saying that chemo was killing everything. The masses that were in my chest had shrunk significantly and considerably.

The reason they called it stage 4 for me is because they found an artifact, but it didn’t show up on previous scans in the hospital. It was an artifact in my lung. That was gone as well. It was a really great scan at that point.

What the doctor said was that everything is going as it is meant to. If everything continued to go that way, I would be okay.

They were careful because I had experienced certain symptoms for more than 3 months. I experienced my diagnosable symptoms for 10, 12 months, like sweating-type symptoms.

Were you able to feel good about the results?

It’s something you want to say gives you hope, but at the time I ignored it. The worst thing I thought could happen was to hope and then have that taken away from me.

I didn’t get hope from everything regarding me. I got hope in other people I met in the chemo suite, whom I made friends with and reminded me of the little things.

Everybody has a different perspective, and I’m not going to say it was the healthiest choice that I made, to not find hope in it.

But knowing myself, I would destroy myself later if that hope was taken away. Then after, if I was okay, I’d let myself be extraordinary happy.

What happened with the post-treatment scan?

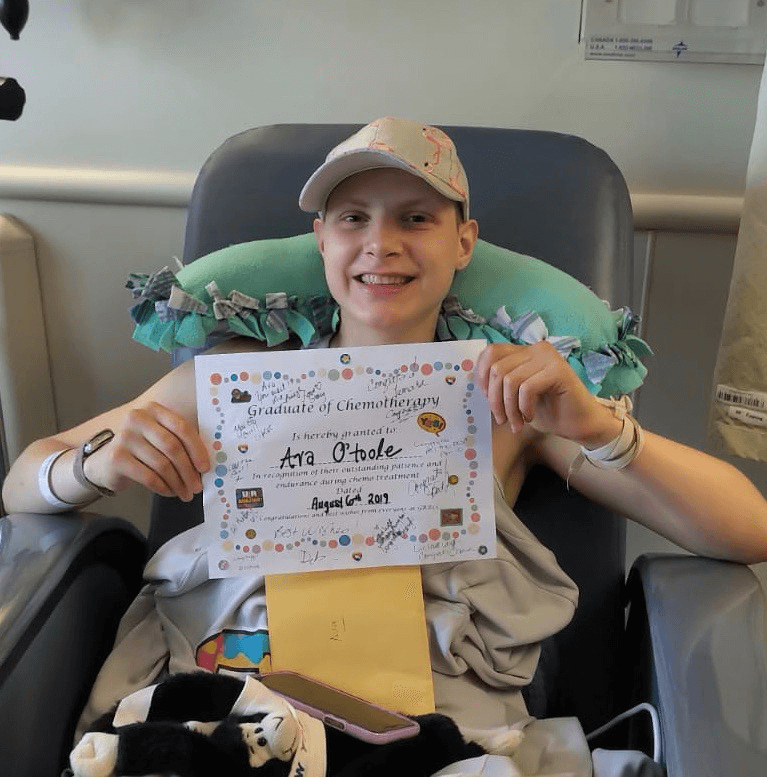

The final scan was in August after I finished my final treatment. That one came up clear! I had my appointment in September to follow up. I had several friends accompany me with my parents to that appointment.

In the waiting room, I had 15 friends, who’d been there from the very beginning with me. They were all waiting out there.

It was a pretty intimidating day. You’re lying to yourself if you’re saying you’re not hoping — you are hoping for the best.

Everything was clear, and I was cancer-free! That was one of the best days of my life and of my family’s life. I felt like I could breathe a sigh of relief.

I didn’t look in the mirror for quite a while. I didn’t want to. I took my mirror off at one point, even well before I shaved my head. For the first time, it felt like I could look into the mirror and see into myself. Not look at me, but see into myself as a person.

How did you cope with “scanxiety”?

Don’t have any expectations. Live in the moment. You have what you have right now. [When] you finish your final treatment, be happy. Whatever that means for you, I can’t say. Knowing who I am and how I’ve always been, was I actually happy compared to who I am? Probably not. But in those moments, for who I was in that time, I was happy. I was happy I finished treatments.

Between that time — it sounds so difficult when I say don’t think about it, but truly don’t. The way you do that is by releasing every expectation you have. That was my strategy. I didn’t even think about it.

I just did everything that I did every day. Those were the things that wouldn’t change. Regardless of what happened, I was still going to drink my water and eat my food and walk my dog.

That idea of scanxiety actually only happened after my treatment. The first time I felt that was when my survival mode was off, when I didn’t feel completely separated from everything else and allowed myself to engage in things again. That only happened after I finished treatment. That took a while to regain without a sense of fear.

»MORE: Dealing with scanxiety and waiting for results

What’s the follow-up protocol?

For the first 6 months, it’s every 3 months (oncologist visits and blood draws). After that, every 6 months. I think after 2 years, it goes to once a year.

Reflections

How has survivorship been?

I learned a lot about what people who face mental illness go through when I finished treatment. I was told I was in remission. It’s like your life is on a silver platter, and you have no idea how to take it.

Your hands have been tied behind your back for such a long time. Now that somebody’s cut the rope, you don’t actually realize you have the ability to move them.

That’s how being in remission felt for me. I was happy, but I didn’t know what I was happy about. You don’t know what to do next. I’d been doing all these things. Is coloring in a book now not doing much for me? What am I supposed to do now?

A lot of people do think you’re okay afterwards. I don’t think it’s their fault, necessarily, but once you can’t see the bag of chemicals, you can’t see the cause of your distress or the trauma that’s left with you.

That’s why I made the comment about learning what people with mental illness go through, because you can’t see inside, and that’s the difference.

Once you couldn’t see it anymore, the ability to understand it seemed to dissipate. In a sense, it’s frustrating in the moment. Try and remember the reason people don’t realize that is because they’ve never had to go through it, which in another way is really beautiful. It should be.

We should have been one of them, and we weren’t, but it doesn’t mean they should be forced to know about it, too. That’s one thing to try to remember in the moments of frustration. It is frustrating to feel like you have to explain why you’re not necessarily okay in certain moments or what triggers you.

I was left with PTSD for a few months, and PTSD is not fun. A lot of people think you’re okay automatically.

The best way I can describe to those people who feel they are not okay is this: who you are will come back like little snowflakes, and little snowflakes melt when they hit the ground.

But if it snows for long enough and you close your eyes while it’s snowing, the next time you open your eyes, you’ll just see a field of snow.

Finding the cancer community

Your account made such a difference for me in seeing other people. It really did. I was of the mind that no, I don’t want to see anything, because I wanted to get through it. A lot of patients I know feel that way.

After the matter, it was something special to be able to see into what other people had been through and to see where they are now, too.

Just to see this is me now, and that could be me, too, in 5 years. That could be me in 2 more months. When you’re recovering or in remission for 4 months, it’s different than being in remission for 8 and 12 months. The place you’re in is so different. So your account has made such a difference for me.

I remember when I sent one of my photos in. It was posted. I had 12 photos and 12 versions of my hair. I remember looking at it and thinking to myself, “Wow, you made it. We made it through.”

How has cancer and the experience changed your life perspective?

I learned the amount of privilege I actually have. The privilege you have of hair, and how differently you’re looked at when you don’t have it. I learned the privilege of life, taking the little things for granted and knowing not to.

It took me half an hour every day to put my shoes on to get myself out of bed. That was the mark for me getting out of my bed. Shoes on, and they didn’t come off until I went back to bed later that night. It was the only time in my life my parents allowed me to walk in the house with shoes on.

When the chemo effects physically wore off and I slipped my shoes on, there were many days when I would walk out of my house or apartment at school and think, “There’s no way it took me that short time to put them on.”

You learn not to take anything for granted. You get to see from a different perspective. You get to see from the perspective of death, and then live. A lot of people don’t get to say that.

People do it different ways, like me right now (sharing my story). Some don’t tell a soul until somebody they know has cancer. Then they tell them, “I’ve been through it. You’re going to push through, and I’ve got your back.”

It’s about carrying that forward. The amount that you learn in your life is what will keep you carrying forward.

I can absolutely say the person I was before I went through chemo and before I was diagnosed with cancer — she was a great person. She was a great girl, but she’s different now.

I’m a different person, and I’m okay with it. For a long time, I wasn’t okay with it, or at least it felt like a long time. You’re able to see things later that you could not before.

I really didn’t like who I became during chemo. I became someone I told myself I would never become. I became that person because I couldn’t be the person I was before. Cancer took that person away from me, so I didn’t want to look at her for a while.

But you get through it. They key is that it changes. It’s normal. The best advice — I got it from 2 friends who battled cancer and had chemo treatments before me — was, ‘You’re normal; it’s fine.’ I forgot things, too. The biggest key is to know it’s normal.

Coming out, you’re scared. You’re jarred when someone taps you on the shoulder. You just are. You jump. But PTSD and all of it changes in time. Just keep remembering who you are. Don’t cling on to who you were beforehand, because there are going to be some things like memory that are going to be different.

Know the person who you were — happier, who was into puzzles, or had a brain that could analyze and put things together — they come back. It just takes time, like little snowflakes. I like who I am.

The other thing I think is a huge part of this is your hair kind of grows with you. Your hair is symbolic of the emotional growth that takes place from the point when your hair begins to grow again. That’s typically when treatment ends.

It’ s a journey no one asks for. No, we shouldn’t have to go through it, but we’re going to, and we do. All we have is what we have, and it’s a different lens to see the world. Be a little more grateful about the little things.

You get a chance to also see who all your real friends are, and not many people have that chance.

So when you live and you don’t have to go through it again, you actually received one of the biggest gifts that most people who never go through it will never have.

Inspired by Ava's story?

Share your story, too!

Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Stories

Jessica H., Hodgkin’s Lymphoma, Stage 2

Symptom: Recurring red lump on the leg (painful, swollen, hot to touch)

Treatment: Chemotherapy

Riley G., Hodgkin’s, Stage 4

Symptoms: • Severe back pain, night sweats, difficulty breathing after alcohol consumption, low energy, intense itching

Treatment: Chemotherapy (ABVD)

Amanda P., Hodgkin’s, Stage 4

Symptoms: Intense itching (no rash), bruising from scratching, fever, swollen lymph node near the hip, severe fatigue, back pain, pallor

Treatments: Chemotherapy (A+AVD), Neulasta