Shyreece’s Stage 4 ALK+ Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Story

Shyreece Pompey dedicated her life to teaching kids. Outside of her family, it was her whole world. Then came the shock of her life: a stage 4 lung cancer diagnosis for this mother and grandmother with no history of smoking.

8 years later, Shyreece is thriving as a different kind of teacher. She is lifting others through her own experience and lessons learned since her diagnosis in 2014, like the importance of patients advocating for themselves, ensuring they get comprehensive biomarker testing that could shift their entire treatment path, the importance of clinical trials, and understanding her experience as a Black cancer patient.

Thank you for sharing your story, Shyreece!

- Video (Part 1)

- Introduction: Tell Us About Yourself

- Diagnosis

- Describe getting the lung cancer diagnosis

- Treatment Decision-Making & Self-Advocacy

- Biomarker Testing & Working with Specialists

- Targeted Therapy & Clinical Trial Experience

- Experience in a clinical trial

- Diversity and Inclusion in Cancer Care

- Final message to others

This interview has been edited for clarity. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider for treatment decisions.

Video (Part 1)

Introduction: Tell Us About Yourself

One of the things that I like to talk about is that I loved teaching before I was diagnosed with stage 4 cancer. I loved teaching so much that it became a part of me.

Now, even after diagnosis, I still teach. The art of teaching, the philosophy of teaching, and everything about teaching is what I love. I did that for probably about 17 years, professionally and even in other aspects in the community.

If there was a teacher needed for something or a class to be taught, I taught. I’m a bona fide teacher at heart, and I think that part of me is a part of me that can never go away. I don’t want to get too deep, but it will always be a part of me.

That is my legacy, just everything that I’ve had to overcome. Teaching is it for me. The people that I come across today, I still teach, but in very, very different ways. In ways that allow them to be their best person.

I was scared, and I said, ‘Something’s not quite right.’ Then I heard a wheezing sound that came out of my body. I said, ‘That’s something that I’m not controlling, and it’s coming out of me. What is that?’

Diagnosis

What were the first symptoms?

Great question, and it’s going to continue to flow with the first question you asked me: what I love to do is teach. Well, I was teaching that day, preparing the students for one of the most important tests ever in the state.

As I was teaching them, I took a brain break with them. We’re dancing; we’re doing the wobble. Then all of a sudden, I got so heavy. My arms got heavy, and I got tired and fatigued. I had to tell the kids, “Y’all got to sit down. I don’t know what’s going on, but y’all sit down. Get out your book and read.”

I needed to sit down for a minute, and there was a throb. There was like a skip, a beat in my chest, and it had to throb and calm down. I said, “I don’t know what that was, but it really scared me.”

I was scared, and I said, “Something’s not quite right.” Then I heard a wheezing sound that came out of my body. I said, “That’s something that I’m not controlling, and it’s coming out of me. What is that?”

When was the first time you sought medical care for these symptoms?

Long story short, probably about a week later after that, I ended up in the ER room. The ER doctor said, “You are not going anywhere. Matter of fact, we’ve got a room ready for you, and I don’t even trust your husband to take you to the hospital. What we’re going to do is put you in an ambulance, Shyreece, and take you to another location.”

That was the beginning of my journey to being diagnosed with stage 4 lung cancer.

When did you first realize this might be cancer?

The first inkling that I knew that I was dealing with cancer was when all the tests that were run pointed to absolutely nothing that was on the surface. It wasn’t pneumonia.

I was like, “Come on, everyone. I have to get back to work. Give me some cough syrup. Give me your cough syrup so I can get back to work.” No cough syrup ever came.

They hooked me up to the EKG to see what was going on with my heart. Perfectly fine. Nothing was coming up. I’m like, “Okay, I’m good. I’m good.” I’m getting excited. I’m good. But then they said, “We have to go inside. We’re going to do a VATS (video-assisted thoracic) surgery on you to drain the liquid that is crushing your lung.”

Now things are getting serious. I’m like, “This sounds deep.” “We’re going to scrape some tissue, and we’re going to send it off.” That’s when I’m like, “Whoa boy, this doesn’t sound good because you’re not finding something on these preliminary tests, and yet something is still gravely wrong.”

“Now you need biopsy tissue.” That’s when it was like, “Oh boy.” That’s when I knew that something deeper may come out of this.

I’m like, ‘Cancer? What is cancer? Give me whatever cancer needs to be dealt with. I’m good. Let’s go.’

The test results

The test did come back that it was a malignant cancer, including the biomarker. The FISH (fluorescence in situ hybridization) test indicated that I had an ALK-positive mutation. That was the beginning of one of the most frightening journeys.

Being the kind of person that I was, I don’t know why that didn’t faze me like that. I was so gung ho about doing something else. I wanted to press through it. I’m like, “Cancer? What is cancer? Give me whatever cancer needs to be dealt with. I’m good. Let’s go.”

Boy, how I wish it was that simple.

Describe getting the lung cancer diagnosis

It took 2 weeks to get an actual diagnosis. All of those tests, and this is during hospitalization. I always go back to the fact that this is a hospitalization-type of moment because my lungs were crushing. That was an indicator that something gravely, seriously was wrong, and it was more than just a cough. It was more than just heaviness.

Then 2 weeks after hospitalization, on the last day, the hospitalist came to my bedside and said, “I’m so sorry. It’s cancer, and it’s stage 4.”

That’s when I had the first cry. I cried on the phone with my cousin, who’s a nurse, and she was living in another state. When I posted on social media that I had to do a VATS (video-assisted thoracic surgery), she called me immediately and knew that.

She said, “Wait a minute. What’s going on?” Then I shared with her right then that they found cancer and it’s malignant. We both cried.

Guidance to other people on processing the diagnosis

The type of person that you are before cancer is important to help you endure that moment. Part of me — yes, I cried and broke down — became very vulnerable, and every conversation that I have ever known that I had with… this is where I bring in the God component. It happens in almost every traumatic moment. It’s like, “Oh, God. I thought this about my life. What is happening?”

In that moment, you want to find reasoning that is spiritual or medical. Every kind of component of philosophy comes into your mind and heart right then. Now I’m reaching for character, right? I’m reaching for moral. I’m reaching for something that can ground me through this moment as to what is being shared with me and who’s there for me.

Who can I call? The doctors are here delivering information, but they are not the ones I want to talk to right now. Who can I call? What could I reach for? In that moment, I stayed there for a moment, but then something on the inside, that part of me is like, “Okay, fine. Fine. If this is what it is, then what’s next? What’s the solution, somebody? I’m like the lady in ‘Wiz’ now. Don’t bring me any more bad news!”

Okay, so if it’s chemo treatment, that’s what they brought to me. Chemotherapy treatment was next. I said, “I’m not waiting. Bring it to me now. Hook it up in the machine. How hard can this be? Let’s do this.”

Now, looking in hindsight, I was like Superwoman going quickly down by the head, and I didn’t know it. Intravenous chemotherapy was hard. They loaded me up, and I was like, “Boom, took it.”

Eventually, I started getting weaker and weaker, and then I really had to reevaluate some things, even the D-word. Not diagnosis. If I’m going to die, then let me start preparing my funeral.

What was your reaction to hearing that it was lung cancer?

Just that I don’t have a history of smoking. Where did this come from? I even thought that it could have possibly come from all the smokers that ever came around me when I was growing up. I blamed them.

I said, “This is smoking-related.” But research and as I continue to grow and learn, the lung cancer and the rarity of it and the complexity of it, it’s absolutely not at all smoking-related.

Within that, it had given me an opportunity to heal on some very mental, spiritual issues that I’ve never dealt with in my adulthood that stemmed from my childhood. I needed that to happen because I needed to know the best treatment plan for me. If it was going to work, I needed to be centered and whole. I needed to be clear.

I need you to know me. I need you to hear what I’m saying to you from me and then going to teach about these different biomarkers.

Breaking the lung cancer stigma

First of all, I really had some of the most challenging statements to me, and that was one: “When’d you smoke? I didn’t know you smoked.”

That stigma alone was something to deal with. Based on my character, I tried to find the most Christian way to respond without getting really, really upset and seeing my other side.

Then again, it became a teaching moment. I said, “Great, I get a chance to teach about my type of cancer and my type of mutation. It’s not smoking related.” I start there.

Then I also let them know that I’ve never smoked. Yes, I grew up around a smoking environment, but that is not the cause of this cancer. I had to go into a teachable moment and also let them know that, no, I do not look down on anyone who smokes, but I know that that’s not my story.

For you to understand that smokers are just not the only ones who can get lung cancer, I need you to know me. I need you to hear what I’m saying to you from me and then going to teach about these different biomarkers.

That’s one of the major approaches, that I use it as a teaching moment now. That’s what I was trying to say before. My teaching skills and degree and everything about it and my talent for it never go away. I just use it in a different form.

I don’t know why I got this lung cancer. I reserve the right and the stance to say that. I am shocked that a non-smoker can get this. It’s not saying that I don’t love you or I’m judging someone if they did smoke. No, all I’m saying is that I want to make sense of this. Make this make sense.

Treatment Decision-Making & Self-Advocacy

Video (Part 2)

Describe the first treatment conversation with your first oncologist

I’m so glad that we get an opportunity to go there, because the first oncologist was appointed to me as one of the 5 doctors who came to my bedside while I was hospitalized initially to figure out what was going on with my lungs. Why they were crashing, and where is this fluid coming from?

1,700 mL units had to be drained from my right lung. They left half of the liquid in there, reserved for the VATS (video-assisted thoracic) surgery, and they got some more of it out that way.

There was the oncologist that was represented. I had the surgeon. I had the oncologist that was appointed nearby, a local one that came in. I had the hospitalist and a couple of others, maybe a cardio doctor that came in, so that now we can rule out some things.

The lucky one that stayed was the oncologist and the hospitalist. The oncologist there was sharing with me because now we’re asking her about prognosis. This is critical. You’re at my bedside, and you’re sharing some things with me.

First, it was like, you know, you’re talking that way. In another breath, you’re like, “Oh, you’ve got about 15 months to live.”

I’m like, “Whoa, that changes the whole gamut of things. Well, what can we do about this?” She said, “I can start you on…” They call it the “salad mix.” I’m not going to even try to pronounce all the medical names that go with that (carboplatin, pemetrexed, bevacizumab).

Then I knew deep down. I said, ‘I think I need to go somewhere else.’

When you decided to get a second opinion?

Most folks in the community of survivorship or cancer patients, you know that there is a mixture of intravenous chemotherapy to try to stop and reverse the cancer in its place. I did that for about 3 cycles, 3 weeks with this local oncologist who knew absolutely nothing about the different biomarkers and how to treat these different mutations.

I know that for a fact because the different treatment plans she had me on were killing my cells. I was dying quicker, it seemed like. It was like, “Wow, this doesn’t look like it works, and I have to stand up for myself.”

Plus, it was like a treatment that she was giving that — I’ll just say it because it’s my story — was the same treatment that she would give a smoker. There, I said it. Same treatment, stand in line.

Matter of fact, when I went there, there were people literally lighting up cigarettes waiting outside somewhere to get their treatment, and there were signs in the bathroom that said, “No smoking allowed.” I’m like, “Wow.”

Then here it’s like, “Okay, stand up. Your turn. Stand in line. Roll up your arm. Or do you have a port? Do you have a port? Okay, well, use your port. Put this in there.”

It was like, “Whoa, wait a minute. Wait a minute. Wait, stop, stop. Wait, can you tell me? Can you pinpoint to me where exactly is my cancer?”

I’m not going to say that doctor’s name because I don’t have her in the best light. I brought her a coloring sheet. I used one of her brochures in her clinic, and I took and drew the lung shape. I said, “Can you tell me which one of my cancers is in your brochure? What does mine look like?” She really, really didn’t have the best answer for me.

When I did that, here’s the big insult. She said to me, “Shyreece. You have monkeys in your head, and they’re speaking to you. You need to just stop listening to them and accept your diagnosis.”

Then I knew deep down. I said, “I think I need to go somewhere else.” I followed that hunch. I went to University of Michigan, where I learned that there are different mutations and that I have options.

I did not need to do right away the intense, hard, chemically-altering cell intravenous chemotherapy treatment that they had me on immediately. That came to a stop immediately.

Guidance to others on patient self-advocacy

Stephanie Chuang (The Patient Story): Even as an advocate, I feel like there are moments when you don’t want to be the “bad patient,” and you want to say, “Well, you know what? The doctor knows everything. They know what’s best. They’ve got all the medical training, so I should just listen.” And it’s hard. Can you help give people guidance here? What can motivate them to say, “No, I need to speak up for myself. I can and should speak up for myself”?

Here’s the teacher-type skill in me coming back out again. There’s a concept called Kagan strategies. It allows people to come together and interact in a way that you can move and get a goal done, accomplished, completed.

You help folks get together and have a camaraderie of spirit so that the end goal would be the best practice for that patient, project, individual, whatever we’re going for.

When it comes to me, I know how to collaborate and get whoever is on my care team. That’s the homework that I have to do. It’s like, “Okay, this doctor specializes in this. This one is needed for side effects. This one is the neurosurgeon.”

I need to see how they all are [and] why they are on this team. First of all, that’s homework. Why are you on this team, Team Shyreece, Patient Shyreece?

When I know that and something that’s going on with me, I can say, “This may fall in these 2 categories, so let me get these 2 in a conversation.” I do it through my patient portal, or I’ll write down questions so that I can take it to my appointment and compare notes.

At the end of the day, the patient has to decide exactly which way you’re going to go to what’s been presented to you. If you are presented with options, I have to look at the data that I’ve been collecting and the anecdotes. Sorry if I’m using too many teacher-type behind-the-scene concepts, but that’s what I use now in order to make data-driven decisions.

Biomarker Testing & Working with Specialists

How did you get the second opinion?

Stephanie Chuang (The Patient Story): It’s an important message for people. Going back to this biomarker testing, I want to really dive into this because it had not been brought up at all in your first conversation, right? It was, “Skip to this harsh chemo, and that’s that.” You go to a second opinion. You get a second opinion. What did the doctor say there?

We’ll go back a little bit [to] while I was being hospitalized. Then, unbeknownst to my knowledge, the biomarker testing and all that had already been done. They took my specimen from the VATS (video-assisted thoracic) surgery and sent it because it’s a local hospital in a rural area.

They took my specimen, shipped it off, and sent it off to the nearest university, which was about 2.5 hours away. When they received it, they ran all the tests on it and sent the report back to the hospitalist.

The hospitalist knew to do that in the first place because he was from the University of Michigan. University of Michigan were the ones who’d done the biomarker testing. The hospitalist called in the local oncologist and said, “Okay, this is a cancer patient. Ball’s in your court.”

That local hospital did not have access to the [report], or I don’t even know if they knew how to read all of the report. All they knew was [for] lung cancer, you stand in this line. Lung cancer goes to this line, when there’s 15 or 16 different aspects.

I’m speaking more intelligently now because I’m speaking in hindsight. But then, it’s like, “Oh, I don’t know.” I said, “Let me just go to University of Michigan and find out.” Yes, I had some options.

Biomarker tests may lead to new treatment options

One of the options was through a targeted chemotherapy. The local oncologist knew nothing about it. The local doctors that I had knew nothing about it. It wasn’t even in their database.

That’s a whole horse of a different color. If I had enough time to spend the rest of my life advocating a thing, that would be why doesn’t the local, rural — that’s where most folks who are living just above poverty. I was a teacher with teacher salary; we have to go to those kind of doctors and clinics. It’s in our area. Why are they not knowledgeable of the different biomarkers?

Working with a lung cancer specialist

Stephanie Chuang (The Patient Story): It’s incredible because it shifted your entire trajectory. It’s an important point for me, too, is understanding and why we do this at The Patient Story. We are trying to reach people who don’t have access to the big research academic centers, who already have people who work both in clinic and in research, know about all these things, and know all the latest developments. This information does need to get out to the millions of people in this country who go to rural, community cancer care centers.

I also do understand that there are a lot of general oncologists. They do their best, and they’re trying to keep up. What I will say is that’s why there are these partnerships, right? You can go to your local oncologist. But if you know to say, “Hey, I’d like for you to work with so-and-so who’s at University of Michigan or UCSF or Mayo Clinic,” wherever, you can have that partnership. I think an important point here, too, is the right doctor is okay with that, right? There’s no ego there. There’s yes, I have my strengths, and I need you as a specialist.

Work together as a team. I don’t know why we’re territorial. I don’t know. Where does that come from? Because it doesn’t help a patient like me. It doesn’t help us.

We need you to collaborate and work together. I need the site, the palliative care doctors, the PCPs, whatever you want to call. You have a meeting every once in a while.

In the education world, there are diagnoses that can help in a student’s life, but it doesn’t keep them there. We’re just saying that today you’re wrestling with ADHD. Today, you may need a 504 plan to help you with your behavioral needs.

Guess what? We have to have meetings. We bring in all the professionals, we bring in the teachers, we bring in their doctors, and we bring in their parents. Everybody sits around the table to develop that plan.

My goodness. To me, it’s just simple. How about my doc? I’ll just keep it personal because we’re talking about the patient’s story. Here’s Shyreece’s dream, and it might happen after I’m called home to glory. But I would sure love to see the day where the oncologist, the neurologist, the neurosurgeon, the radiologist, and everybody just have a meeting every once in a while. Maybe every year, once a year, or every 6 months.

I know you are busy. We thank you for all that you do, but please consider coming together just to have a patient review with everyone that’s involved. That’d be great. Thank you for your time.

How did treatment options change after the ALK-positive result?

Stephanie Chuang (The Patient Story): With the biomarker testing, it turns out that you were ALK positive. For people who are not familiar with biomarker testing, it’s also known as genomic testing or mutation testing. You’re trying to figure out if there is a driver mutation that’s targetable. That’s what you were saying about targeted therapy, right? ALK positive for you. That was the targetable mutation.

[My oncologist] just said, “Here are some options. I said, “I’ll take door number 3.” When I picked it, which is the targeted chemotherapy, he said, “I have to run this by your insurance.” I’m like, “Oh, insurance, what?” Now, there’s another topic.

They ran it by the insurance, went through that process, and waited for hours just to see if I can go and get the targeted therapy.

I’m so glad that University of Michigan had their pharmacy right there. We’re just talking about special deliveries because I’m thinking, “You can’t just send this prescription to Walgreens so I can go pick it up?” No, honey. We’re going to have to see if the insurance approves it, and if they don’t approve it, that would be a shot to me.

What if they didn’t approve it? I’m glad they did. But what if they didn’t approve it? It’s like, for me, now what? That door number 3 is not available to me. That’s a whole ‘nother conversation.

Let’s stick to [the fact] that it was approved. I had to wait and go get it and then for them to fill it. It’s through their pharmacy only. I would have never been able to get it anywhere else anyway. That’s why nobody else knew about it.

Targeted Therapy & Clinical Trial Experience

Video (Part 3)

The targeted therapy experience

I started taking [targeted therapy] in April. One month after diagnosis, I start a whole new world, and I can cry. The day was sunny. I’m sitting in the car with my husband. We leave University of Michigan to take this new elixir of knowledge in this bottle in the form of pills. I can’t even remember how many a day I had to take with crizotinib, the first one, and so I started taking them.

We had our lunch, and then not too much time went by until I felt different. I did feel the side effects of it a little bit, but some things started kind of clearing up a little bit in my throat area, where I was always challenged after surgery.

I started being a little bit more tolerable to what was going on with my body. I felt different. I said, “Wait a minute, something’s different.” I lived 3.5 years on it.

I maintained side effects, but I also knew when it stopped working. That’s a scary place to be also. That’s when I knew I woke up to another reality is that I can’t put all my hope into these targeted treatments. So now what?

Experience in a clinical trial

Stephanie Chuang (The Patient Story): I think it’s good for patients and caregivers to have those expectations set. I also love that you’re talking about the need for constant research. This is why clinical trials are so important, because you’ve got these, like crizotinib, that were approved, and you just need them to be approved in time for you.

But then at some point, you know that there’s resistance and the cancer sometimes finds a way around it. So what’s the next thing? That’s why these clinical trials are constantly being done. Do you have a message about that, the importance of clinical trials and that research, what it means to you?

I am all in for clinical trials and research. I participated in a clinical trial during a May 2015 through to July 2015. I remember like it was yesterday because that’s when I made the decision to come out into retirement.

I could not do the clinical trial at that time. It was very intense. It was like three times a week driving the University of Michigan, which was two and a half hours. Then there were complications, and understanding was this clinical trial that I was participating in. Would there be any help to me in regards to gas and transportation? That got confusing with the university and so we worked through that.

I wanted the world to see this process of this new strange lung cancer that’s rare. No one’s ever really heard of it before.

There’s a resolve that in this journey, it will require three components of you. Mind, body and spirit. You cannot afford to ignore any one of those components.

Importance of more diverse representation in clinical trials

Look at me, I don’t know if you noticed, but I’m Black. I was trying to figure out is there anybody else that looked like me that has this?

Yes, I am all for clinical trials, and that’s another thing. I just like being transparent and I like being authentic and real. There are not a lot of African-Americans who participate in trials in the first place, but I did. I went on ahead and did it.

I didn’t like how it was working with my body. And so by July 2015, the physician assistant, I just love her to death, at University of Michigan. She looked at me in my eyes and she said, Shyreece, this is not the quality of life we want for you, and you don’t have to do this. So because I was having a bad time with it, so she pulled me off of that.

I participate in trials and I do support research where I can.

Stephanie Chuang (The Patient Story): I think there are a couple of points there. One is clinical trials are, someone put it as tomorrow’s treatment today. Sometimes it can give you access to something that’s not yet on the market. And the other part is helping people for research.

What is your message overall to the patient, to the caregiver right now who’s watching this, who’s a little bit nervous, who knows, logically speaking, or rationally, I should speak up, but it’s a little bit hard to do in the moment.

You have to have a resolve. There’s a resolve that in this journey, it will require three components of you. Mind, body and spirit. You cannot afford to ignore any one of those components. They all have the same level of importance to your overall well-being, as well as how effective the treatment is going to work.

Everybody is different. That’s correct. But one thing remains a fact, and I wish that there was enough time to do scientific research on the survey that most cancer patients must complete prior to their return visit with their doctor.

The survey asks how are any one of these everyday circumstances under these categories, family, spiritual, financial, affecting you this week on the scale of one to 10?

And if your spiritual balance and inward being balance is off, that will affect the success of the treatment being prescribed to you. So keep that in mind on your journey – mind, body and soul. All three of those components are equally important as you journey in your cancer walk.

Shared treatment decision making between doctor and patient

Stephanie Chuang (The Patient Story): When you think about the patient doctor relationship and the paradigm we’ve been living in, where it’s shifting, but it’s still slow, from doctor knows best, I will sit here and listen versus I need to be in charge of my own cancer care or my healthcare in general. What is that message to doctors, to patients about the need for more patient self advocacy, for more listening to patients?

First of all, I would like to take this opportunity as we’re winding up that section to thank the collaboration of all of the doctors, especially the ones that I’ve had at University of Michigan, as well as Stanford Health Care. I think that they are a phenomenal team.

The minute that I walked into Stanford Health Care, they knew my back story. There’s a word on the street, back story, what’s your back story? Then they’ll say, well, I’m just living my back story right now. Well, Stanford, they knew my back story. I was shocked about that and they looked at it intently. They had a plan of where they would like to go.

It was easy for me to trust in that. So there were some components that I was looking for in their approach. They say the first impression, it’s important. So they had a great first impression, which was, ‘Let us take a little time. We don’t need you to fill out the paperwork of a new patient today, Shyreece, just to know you. No, we went and did a little background work on you.’ So to know the patient is very important to me.

Own your data.

If somebody is going to take the time to know you, then yes, that’s a good starting place to where we can enter into a healthy collaborative. Now I have to say collaborate still, because this is my temple. This is my temple. I am not a guinea pig. I’m not a lab rat. This is my temple and nobody walks in this temple but me.

So, yes, there are some parts of me that I have to bring to the table because I can’t expect them to know everything there is to know unless I tell them. There are some things that I have to share as well. So it’s going to take that collaboration.

Also, when you’re presented with options, that’s all they’re doing, is presenting you with options. At the end of the day, you have to make a decision.

So my advice is, look folks, study your own data when you’re presented with some options. The doctors may not know everything before your cancer diagnosis. They’re not gods. They’re your doctor, so have a participative approach to your care.

Own your data.

Diversity and Inclusion in Cancer Care

Video (Part 4)

Amplifying diversity in healthcare and research

Stephanie Chuang (The Patient Story): We know that Black men and women with lung cancer are significantly less likely to get diagnosed in an early stage compared to their white peers. If you’re getting diagnosed later, the odds of survival are smaller, right? But there is a lot of human impact here that I want to unpack. What is your message in terms of what we all need to do better? Whether it’s clinical trial participation, whether it’s messaging to the Black community, what do we need to be doing?

It’s definitely not in the rural areas yet, it’s coming, but there are some African-American initiatives community movements where on the health front, they’re really going into communities and neighborhoods.

They’re setting up fairs and booths and handing out literature to where you can really be active in your health on all fronts, whether it’s lung cancer or breast cancer awareness, all of it.

Reaching faith-based communities

I do know that it’s not enough, though. It’s not. So much more to be done, but it’s a start. Within those communities, and I’m just going to be brutally real, it might have to creep into our faith-based communities because even I have to continue to combat this as a believer.

I do attend church, but I’ve also learned how to grow in this challenge of having cancer. I have the opportunity to see both sides as a cancer patient and as a participant in church activities. So the disconnect is that, and this has happened to me a lot. ‘Girl, just give it to God. Just pray.’

As if the God that I’m praying to is not going to answer through people. When that realization hit me, I was like, oh, He’s going to answer through people when He does, so people, how can we get ourselves in a position to actually do some really wonderful things?

I think that that aha moment is going to come from let’s get out of being territorial first. We do have some owners of the information, ‘this is our information and it’s going to stay in our university.’

There’s that extreme, to just providing the information through flyers. You go to a church gathering and present, I don’t know, have a day of food and medicine. I don’t know. We can be creative, right? I hope.

If you give a man a fish, he’ll eat for the day. You teach a man to fish, he’ll eat tomorrow. But how about we show them where to fish?

Improving outreach to Black communities

Stephanie Chuang (The Patient Story): We’re painting with broad strokes. Black people or African-American communities are not one monolithic thing, but generally speaking, there is a sense of distrust with some folks when it comes to institutions, to healthcare, to testing.

And of course, Tuskegee the experiment is a huge part of this because people from that era are telling their family members and passing that down, okay, you’ve got to watch yourself because we have to protect ourselves.

There are these cultural nuances. So you suggested let’s meet people where they are in the community. Is there anything else that we can do better so that we have more participation?

Oh, absolutely. First and foremost, with all due respect, the first thing outside of race, color, creed – I had to choose if I wanted to live or not. When I decided that I want to live, I started looking at everything through the lens of, okay, so what is the best approach? What is this?

Let’s go back and let’s connect something real quick. The first oncologist who said, ‘You have monkeys in your head,’ I could have decided right then to take that as a total racial write off and just go all into some kind of march or whatever and raise a flag. But I chose not to because that energy would have taken away from the energy that I needed to live.

Because when you talk about monkeys and apes and stuff like that, oh, that can raise an alarm in the Black community in a minute. But for me, I needed to look at the bigger picture. I didn’t need to address her that way. Not at that moment.

I need to live first. Let me find out how to live first. So now I’m reaching for the exchange. Can we get to a place where we can feel comfortable engaging in a conversation?

We talked about the stigma of lung cancer being associated with smoking, then we need to remove the stigma that the reason why people are not getting diagnosed early or vice versa, is it all race related or is it because they really don’t know where to fish?

If you give a man a fish, he’ll eat for the day. You teach a man to fish, he’ll eat tomorrow. But how about we show them where to fish? Where is the information at? I wanted to know, so I sought. I now teach people, not color first, gender first, and all this, but I teach you where to go to find information. Is that where the energy goes now?

Democratizing access to treatment information – for everyone

That way, I can demystify the Tuskegee approach. I’m sorry that happened, it did. You’re right, but that’s not today. That’s not today. So I’ve got to stay present.

So what’s today? Today’s issue is just like we talked about once before, which is the information is not made available to everyone. And University of Michigan had knowledge about a targeted therapy that the local rural area that I lived in had no idea about.

I don’t think all the way that that had anything to do with race, color, or creed, it had to do with the dissemination of pertinent information for just people who are not who are not in the university.

You can never give up hope.

Not now, not then, not ever.

Final message to others

I’ll start with the end and work backwards, which is hope. The hope is in knowing that there’s more to life than just your existence. The hope for me was I joined a lot of groups. I joined a lot of advocacy groups and the hope was always in just the research alone. We don’t know what’s coming out. So there’s that hope in the unknown.

You can have fear or you can have hope. Then when you have hope, what is it in? No different than fear. What is your fear in? I can have fear of my scans. I have a scan coming up the end of April. Now I can have fear of the scans, or I can have hope that when the scans come out, that there is an answer, that there is a remedy. That there is something on the horizon.

When I had that hope at first, that hope didn’t kick in right away, it’s weird, even when I called myself a believer, but in a cancer diagnosis, you’re staring at something that people have died from. That’s a whole different walk because you’re planning your own funeral.

But yet a glimpse of hope came, to know that the crizotinib that I was on didn’t even exist 10 years ago. I did pray and people were praying for me and I know that on a cancer journey, the people that love you, they go into prayer. Well the prayer is that, the hope is that yes, research is changing, and it’s creating opportunities to live longer.

I’ve been living eight years now. You can never give up hope. Not now, not then, not ever. So I get the hope to live longer, but I can’t just hope in the next pill. I need to have a place of peace. I need to have a disposition that even if the next pill doesn’t work for me, can I live a life of giving back because that gives me joy.

I want the next person who’s diagnosed to know that not only can you have hope in the research, but you can have hope in a very divine essence of love. Love is an energy that I know that after the last pill doesn’t work for me, the quality of life that I was able to live because of the cancer research, it’s great. And I’m thankful.

So resolve. Get your place to a resolve where you can enjoy the research and take advantage of it for the quality of life and give back. Give back to your family. Give back to your community. Give back to something.

More on Shyreece’s book

HOPE: It Will Not End with My Death is on Amazon.com. It’s basically my six-year lung cancer journey. The first six years in all of the ebbs and flow of it.

It’s not just about the hospital, so it’s not a boring read to where it’s like she’s in the hospital today and then you’ve got to go get a test. It’s not like that. Anyone, even if you don’t have cancer, can read it and just follow me on this awesome journey. I do call it awesome because there are so many other discoveries of me becoming.

Follow Shyreece

- Queen of Overcome (Website)

- HOPE: It Will Not End with My Death (Book)

- Fruititude: Growing Spiritual Virtues Through Adversity (Book)

- Facebook Page

- GoFundMe

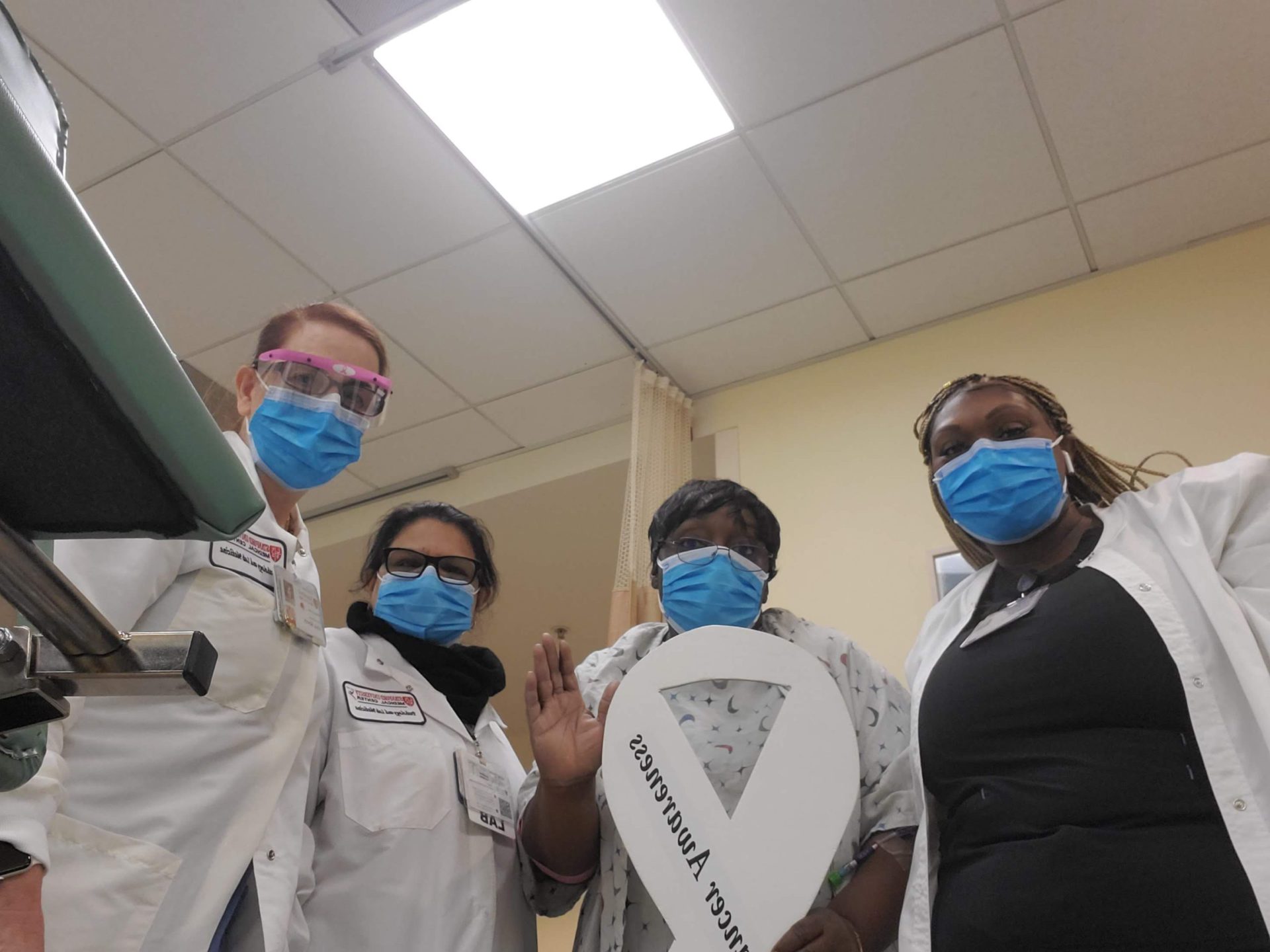

The White Ribbon Project Series

Learn more about one group working in lung cancer advocacy!

Thank you so much to Pfizer for its support of our patient program!