Bill’s Stage 3, Type 1 Papillary Renal Cell Carcinoma Kidney Cancer Story

Bill shares his story of kidney cancer, papillary renal cell carcinoma, and how he shifted from patient to self-advocate to advocate for rare kidney cancers. Read on to hear Bill’s experience with surgery, and more important to him, his path to figuring out treatment where there wasn’t an established standard of care.

Also in his in-depth story, Bill highlights other issues critical to him post-kidney cancer diagnosis, including how to approach dealing with a rare cancer, guidance on how to approach clinical trials from a patient perspective, being your own advocate, and the emergency of personalized medicine or precision medicine.

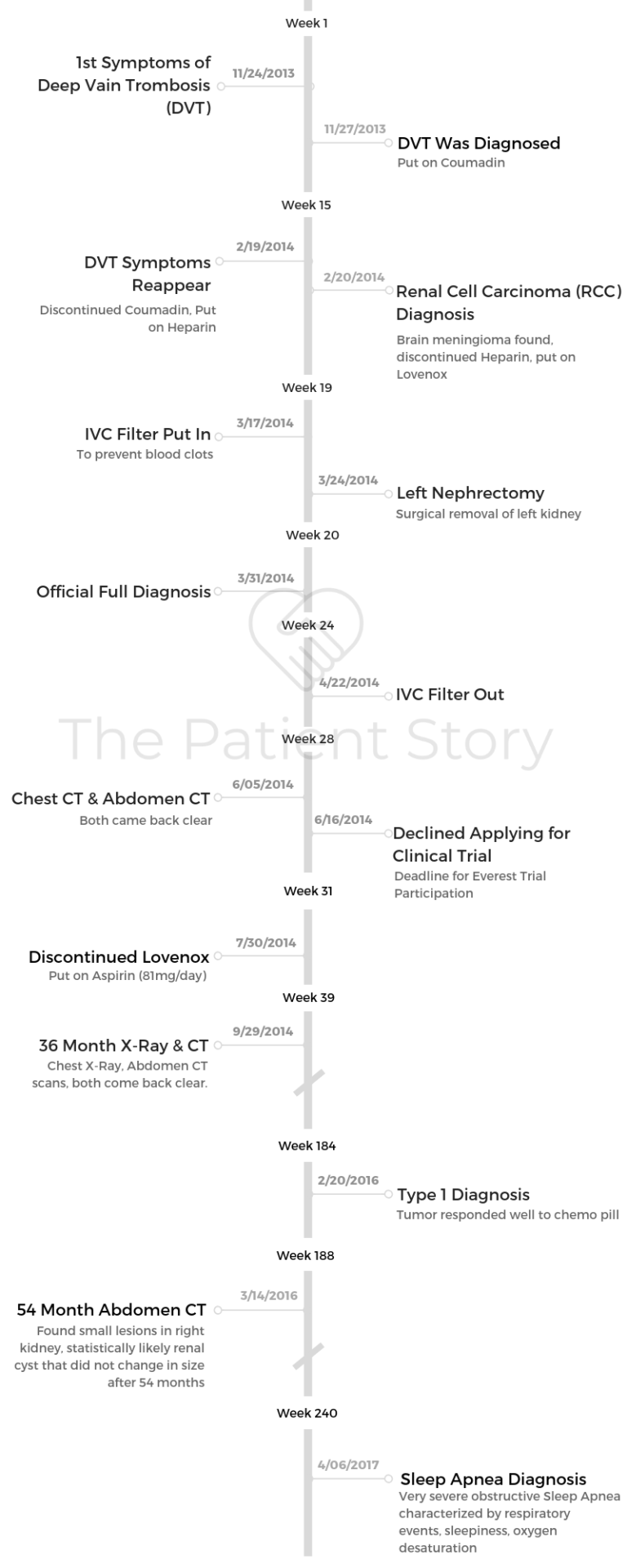

- Name: Bill P.

- Diagnosis (2014):

- Kidney

- Papillary renal cell carcinoma (pRCC)

- Stage 3

- Type 1 (indolent or slow growing)

- Age at Diagnosis: 59

- Symptoms:

- Kidney stone

- Lower back pain

- Sore, stiff leg

- Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) blood clot

- What led to diagnosis

- Ultrasound of left leg

- CT scan with IV contrast of chest, abdomen, pelvis

- Tests for staging and to determine metastasis:

- CT scan with IV contrast of neck

- MRI with IV contrast of brain

- CT scan with IV contrast (renal protocol)

- Doppler ultrasound of upper extremities

- CT angiogram of chest (to examine blood vessels)

- Ultrasound of veins in left leg

- PETCT scan of skull to thigh

- Treatment:

- Total laparoscopic nephrectomy (surgical removal of entire kidney)

- No standard of care

- Abstract: The most important points from Bill

- Path to Diagnosis

- What were your first symptoms?

- Describe the first medical visit

- Describe each test and scan pre-diagnosis

- When did the symptoms reappear?

- Describe the second round of pre-diagnosis tests and scans

- Describe the initial diagnosis

- Describe the post-operation diagnosis

- What was the prognosis?

- What was the exact subtype and stage of your cancer?

- How did you get the cancer type diagnosis?

- Describe the time gaps between your diagnoses

- How did you break the news to your loved ones?

- How did you decide where to go for treatment?

- What were the pros and cons of going to a bigger hospital?

- Treatment (No Standard of Care)

- Describe the scans

- What was the recommended treatment?

- Describe the surgery (nephrectomy)

- Describe the catheter experience post-surgery

- When were you able to fully walk again?

- When were you able to urinate on your own again?

- What happened when you asked professionals whether you should pursue a clinical trial?

- What does “standard of care” mean to you?

- Advice to rare cancer patients on figuring out best treatment options

- Advice to others on how to approach clinical trials

- Rare Cancer Considerations

- “Take an activist stance”

- Here is some stuff I read when it’s been a bad day

- Advice to other patients and caregivers on dealing with doctors in general

- Be your own advocate

- How important is it to have a caregiver?

- Personalized medicine

- What is your hope for rare cancers like papillary renal cell carcinoma?

This interview has been edited for clarity. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider for treatment decisions.

As a patient, I exercise my right to review the doctor’s conclusions or recommendations. My most important question is always the last one: ‘What question should I have asked that I didn’t?’

The doctor is not there to educate me on the basics. Good thing, since most are poor at being teachers, and few are experts in particular rare conditions.

So I became an expert in my own condition.

Bill P.

Abstract: The most important points from Bill

- Recognize that you have no standard of care. This means that your journey will be unique, and to make an informed decision on your path forward, it helps to become a student of your disease.

- Especially if you have a rare disease, create a complete list of specialists and their locations. SmartPatients can help here.

- It’s a developing situation, so you need time to discover what is going on. You will be on pins and needles as your situation develops.

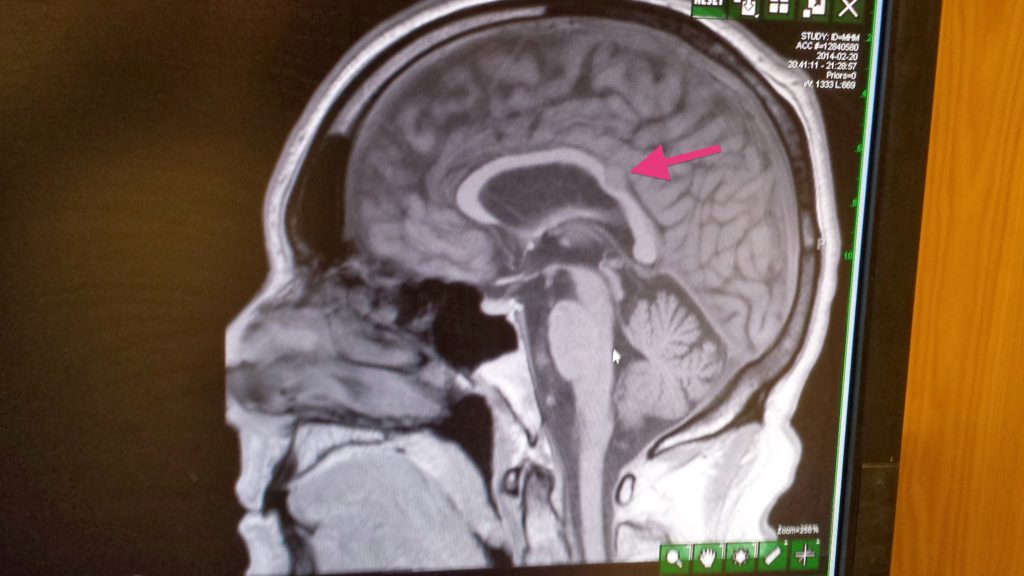

- Example 1: Initial scans showed masses in kidney, lung, neck, and brain. After a day or so, they realized that the neck scan was a mistake. The lung spots were not very big, so they guessed that they could ignore them (for now). Given that assessment, they guessed that the brain tumor was a benign meningioma, not a kidney metastasis.

- Example 2: There was no biopsy, so the doctor’s initial assessment was clear cell kidney cancer (based on statistics). After the operation, they determined that it was papillary. Again, it took several days.

- Example 3: Took two years before I finally knew what kind of papillary.

Path to Diagnosis

What were your first symptoms?

- Sept. 13, 2013: Kidney stone diagnosis. The doctor attributed the kidney stone to chronically elevated uric acid levels.

- Nov. 25, 2013: Developed sore, stiff left leg while on a business trip.

My wife reminded me that I had lower back pain at that time. We bought a nice, new bed to alleviate the symptoms.

Describe the first medical visit

Nov. 27, 2013: Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) diagnosis. I assumed DVT was due to sleeping in cheap seats on cross-country flights. I returned home the day before Thanksgiving.

I had leg pain that did not go away, so I went to my doctor. He was ready to go home, but when I showed him my symptoms, he dug up an ultrasound technician who verified the presence of a DVT (clot) in my leg. The danger of such a clot was that it could dislodge and go to my lungs and create a pulmonary embolism (fatal) or to my brain and create a stroke (fatal or debilitating).

The doctor immediately put me on an injectable blood thinner called Lovenox, like heparin but does not require an IV, and later Coumadin, which is also called warfarin.

Describe each test and scan pre-diagnosis

- Dec. 22, 2009 & Oct. 18, 2011: Urology visits showed high uric acid

- Nov. 27, 2013: Ultrasound of the left leg. Non-occlusive thrombus is visualized in the LEFT mid-femoral veins to the popliteal veins.

When did the symptoms reappear?

Feb. 19, 2014: DVT symptoms reappeared, and I was admitted to hospital. I went to the Johns Hopkins emergency room and was admitted for an examination since the doctors wanted to find out why I still had clotting symptoms while taking anti-clotting medicine.

Describe the second round of pre-diagnosis tests and scans

Johns Hopkins Hospital (Baltimore)

- Feb. 19, 2014: Ultrasound of left leg. Near occlusive thrombus is identified in one of the mid-femoral veins and the distal femoral vein.

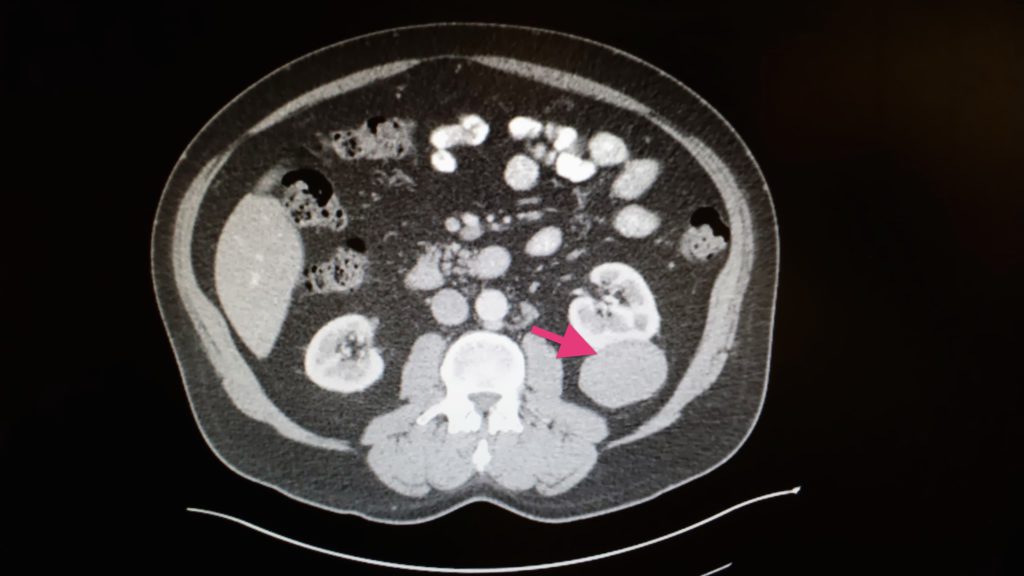

- Feb. 20, 2014: Kidney cancer diagnosis after CT of chest, abdomen, pelvis with IV contrast shows a 5.7×4.8cm mass in the left kidney. MRI of brain showed meningioma.

- Feb. 21, 2014: CT with IV contrast to focus on spleen. Ultrasound shows no evidence of DVT in lungs.

El Camino Hospital (Mountain View, CA)

- Feb. 28, 2014: Angiogram of chest shows no evidence of pulmonary embolism.

- Mar. 3, 2014: Ultrasound (Venous Duplex) shows DVT in upper leg.

- Mar. 6, 2014: PET-CT scan of skull to thigh showed cancer did not appear to have metastasized.

Describe the initial diagnosis

After two days at Johns Hopkins Hospital, I was in the shower, cleaning up. The hospitalist asked, “Where are you?” I said, “Getting ready to go home.” He said, “Maybe not.”

I came out, and he showed me my brain and kidney cancers. I then taped his description.

This was the year that Obamacare kicked in. Fortunately, my wife had bought trip insurance for the Baltimore trip. The trip insurance company said they would pay for my Johns Hopkins Hospital stay due to the DVT.

However, cancer was not an “emergent condition,” so they wouldn’t pay for the surgery. Also, since I was a California resident, if I stayed in Baltimore for the operation, I’d have to pay full freight. So I went back to California where I was insured.

Describe the post-operation diagnosis

The operation (total left nephrectomy or surgical removal of left kidney) was delayed by a UCSF nurses strike. Ultimately, this “critical” operation happened more than a month after the diagnosis.

In addition, the pathology report stated that the cancer was not clear cel” but papillary.

What was the prognosis?

Rare, untreatable, and terminal. There are two forms of papillary kidney cancer: type I and type II.

Type I is indolent (slow growing), and type II grows a lot faster. I asked which one it was, and the surgeon said that UCSF pathology could not tell.

What was the exact subtype and stage of your cancer?

Test results showed:

- pT3aN0M0 RCC (Renal Cell Carcinoma)

- papillary type (5.6 cm)

- Fuhrman grade 2

- focal extra capsular extension

- margins negative

Good news: N0M0 meant the tumor had not gone into the artery, vein, kidney connection to the bladder, adjacent lymph nodes, or traveled to distant organs.

Bad news: pT3a meant it entered the sack that kept the kidney separate from the rest of the body. Officially, I was cancer-free with a “high risk of recurrence.” T3a typically has a 5-year survival rate of 59-70%.

How did you get the cancer type diagnosis?

I wound up co-founding a group called Rare Kidney Cancer with Dr. James Hsieh and discovered that the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in Bethesda (Maryland) handled a lot of papillary kidney cancer cases. I paid UCSF to send slides to the NIH for a more detailed exam.

By phone, the NIH kidney specialist told me that I had papillary type I, the slow-growing form. I was pleased.

Describe the time gaps between your diagnoses

For the first one-month delay, I got the operation scheduled as fast as possible, but as I described, changing insurance and the UCSF strike delayed it more than a month.

In retrospect, it may have been better to just pay $100,000 for an immediate operation at Johns Hopkins out of pocket.

For the 2-year delay, from the doctor’s perspective, there is no standard of care for any papillary renal cell carcinoma (pRCC). Suppose he identified to the allele the exact genetic mutation that caused my cancer. It doesn’t change treatment options since there is no treatment.

Radiation doesn’t work; chemo doesn’t work; immunotherapy doesn’t work. Why do a biopsy to identify a mutation they can’t treat?

From my perspective, it was helpful to get the type diagnosis to estimate how much time I had left.

A key point here: I’m not dead yet, illustrating that statistics don’t predict individual cases.

Also, perhaps, ‘Ask not what disease the person has, but rather what person the disease has.’

How did you break the news to your loved ones?

My wife was with me at the hospital, so she knew when I knew. I called the kids to bring them up to speed on what happened. Two were concerned. One, when told that I might die during the operation, said, “Everybody dies eventually.”

Not a fun revelation, but the key point is that I’ve only been able to see the true nature of an emotional connection when that connection is under stress. Also, even inside the family, for me, sustainable relationships are based on common interests.

As my relationships changed after we had our first child (less “guys at a bar” and more “father of your child’s friend”), it became clear that cancer, like childbirth, had the potential to be a relationship-changing event. So I kept my condition quiet with most people, but used it to expand my relationships with a new group.

»MORE: Breaking the news of a diagnosis to loved ones

How did you decide where to go for treatment?

[I] wanted to go to the best guy, so I asked my gastroenterologist brother-in-law for the name of the best guy on the West Coast.

I figured that my brother-in-law would do a good job, because if I died, he would have to deal with his sister.

What were the pros and cons of going to a bigger hospital?

In a big hospital, the doctor became the best because he practiced a lot.

However, I had to deal with longer wait times and a hospital strike.

Treatment (No Standard of Care)

Describe the scans

MRIs are big, loud, claustrophobic machines, but they draw no emotional reaction from me. I have had enough scans to be able to tell when the operator is incompetent.

That’s kind of scary. It was not clear to me what to do in that case. I hate contrast. I know it is working to destroy the one good kidney I have left.

I do, however, have a fun memory of the bathroom next to a PET scan. Don’t remember the exact wording, but it was something to the effect of, “Please sit down when urinating. Otherwise, you may splash radioactive contamination all over the bathroom.”

Finally, for one brief moment, I realized a childhood dream. Radiation briefly made me a super-powered mutant: Urination Man.

What was the recommended treatment?

Total left nephrectomy (surgical removal of left kidney).

Describe the surgery (nephrectomy)

It took several hours. I elected for a total instead of a partial removal. Nasty tradeoff.

If they took too little, they might miss some cancer, and it could come back. If they took too much, I would have to go on dialysis if the other kidney failed, and eventually die from that.

I decided I’d rather die of kidney failure than an untreatable cancer. Kidney failure has a standard of care.

Describe the catheter experience post-surgery

Not fun. Despite my research, it was unclear to me how big a deal that was. I was not emptying enough of my bladder fast enough. Also, having a pretty nurse impersonally handling my private parts really drove home that I was 60, not 20.

When were you able to fully walk again?

Same day. They insisted that I walk a lot. In fact, when I went home, I got a standing desk to help heal faster.

This advice came from a nurse when I asked, ‘What question should I have asked but didn’t?’

When were you able to urinate on your own again?

Two or three days.

What happened when you asked professionals whether you should pursue a clinical trial?

According to my surgeon, I was eligible for a clinical trial called EVEREST. I asked 13 professionals if I ought participate in EVEREST. Responses:

- Yes:3

- No: 5

- Patient must decide: 5

The pivotal opinion was given to me by a specialist from Houston: “I do not recommend any adjuvant trial w/ mTOR inhibitors or VEGF targeted agents for papillary RCC. There will be trials with immune checkpoint agents in the near future, but not soon enough to enroll on.”

So I decided not to enter the clinical trial.

»MORE: Learn more about the process of clinical trials from one program director

What does “standard of care” mean to you?

An analogy works best. If I break my arm and go to a doctor, each doctor will give me the same examination, recommendation, and treatment. That is because broken arms are not unusual.

All doctors are using the same standard for treatment, the same standard of care. In fact, if the doctor deviates significantly from the standard of care — for example, shaking a rattle over the wound) — s/he can be and often is sued.

Clinical trials are not standards of care. They are unproven educated guesses about what might work. Here, doctors are allowed to shake rattles, “so long as they use a double-blind study.”

Finally, one hematologist I interviewed made a key point: “Metastatic kidney cancer has had no successful treatment (e.g. radiation, chemotherapy, immunosuppressants). So patients with the affliction usually just wait, hope, and live out their lives. If you participate in a clinical trial, you would certainly further scientific knowledge, but chances of success are low.”

Advice to rare cancer patients on figuring out best treatment options

Go to sites like Kidney Cancer, Clinical Trials, Rare Kidney Cancer (note: Bill’s website) to discover who the specialists are, pick the one that makes the most sense for you, and start a conversation.

You do not have to change your existing physicians to do this. I attended the International Kidney Cancer Symposium to make my initial contacts. [I] talked to lots of doctors.

I wanted to open with one question: “How do we get pRCC treatments faster?” Instead I opened with a question suggested by the SmartPatients moderator: “How do we get more pRCC patients in clinical trials?”

That question speaks to their interests. Most conversations died, but one led to a collaboration with my Rare Kidney Cancer co-founder, Dr. James Hsieh. Getting inside the community at events like this got me a lot more information.

Advice to others on how to approach clinical trials

- Understand the trial. Trade off your situation with the potential outcome. I decided not to participate in EVEREST (an adjuvant trial) partially because of this.

- Try to get your blood, tumor, and kidney sequenced while it is still fresh. This helps you seek out trials based on mutation, not just condition. This information also helps you participate in research events, like this one I participated in, while not poisoning the well for any future clinical trial activity.

- Keep some tissue in reserve in case it is required for future trials.

- There is financial aid for some trials.

- Help advocate for “open clinical data” and “pan-cancer research.”

Rare Cancer Considerations

“Take an activist stance”

I believe that if the disease is rare, you won’t have much help, and so patients need to take an activist stance.

Some join groups that explore their particular disease. Some take a broader position (e.g. I like “open clinical records” and “pan-cancer analysis”). But ultimately, I believe Franklin D. Roosevelt nailed it:

‘Take a method and try it. If it fails, admit it frankly, and try another. But by all means, try something.’

Here is some stuff I read when it’s been a bad day

My second favorite movie, “The Martian,” really sets the tone for me on individual attitude when approaching this. Replacing “space” with “cancer,” the closing scene reads:

“The other question I get most frequently is, ‘When I was up there stranded by myself, did I think I was gonna die?’ Yes, absolutely. And that’s one you need to know, going in, because it’s going to happen to you.”

This is cancer. It does not cooperate. At some point, everything is going to go south on you. Everything is going to go south, and you’re going to say, ‘This is it. This is how I end.‘

Now you can either accept that, or you can get to work. That’s all it is. You just begin. You do the math; you solve one problem. Then you solve the next one, and then the next. If you solve enough problems, you get to come home.

My favorite movie, “Iron Man,” features a fellow MIT graduate, Tony Stark, who gets his head set straight with a comment from a friend who is in the same situation as him, stuck in a cave in Afghanistan, shrapnel working its way into his heart with people outside ready to kill them both.

Tony Stark: I shouldn’t do anything. They could kill you. They’re gonna kill me either way, and even if they don’t, I’ll probably be dead in a week.

Yinsen: Then this is a very important week for you, isn’t it?

Advice to other patients and caregivers on dealing with doctors in general

One small but vital point: doctors have two duties that are in direct conflict when you have a terminal disease. One is being frank. The other is providing comfort and hope.

The result can be sunshine-y answers to questions. You have to decide what you want. Some people prefer hope to frankness. I prefer frankness to hope.

So I tell the doctor that I recognize the conflict, but would prefer direct answers to direct questions. I can usually get those when interacting face to face. Email is harder, but I was fortunate that the specialist from Houston responded to my second email request for an opinion.

Being frank is not the same as being true or being right (unfortunately). The best you can get from these guys is information. You have to determine what is right yourself.

Be your own advocate

In addition to being an existential threat, my disease is rare (which means no research), untreatable (which means no standard of care), and terminal. Don’t know where the line is, but here, self-advocacy is probably warranted.

In my opinion, the right question is, ‘When should the patient educate themselves about their condition, when should they create their own care team, and when should they just trust the doctor?” Answer: They should educate themselves and create a team in all cases.

Helping my parents in their last days [and] having a nurse as a sister-in-law and a gastroenterologist brother-in-law have given me some exposure to the medical system from both the provider and patient side.

The key experience that forged my attitude was watching my nurse sister-in-law spend the night at the hospital after my wife gave birth (three times). She checked every pill, vial, and procedure and listened to every consult. Occasionally, she slept on the floor. Once, she prevented an unnecessary transfusion. My takeaway? Two points:

- Since trust is a poor substitute for knowledge, every patient must either have a friendly sister as a nurse or be their own expert or advocate. When I write computer programs, I have someone else review and question my work because it helps me do a better job. As a patient, I exercise my right to review the doctor’s conclusions/recommendations.

»MORE: How to be a self-advocate as a patient

My most important question is always the last one: ‘What question should I have asked that I didn’t?’

- The doctor is not there to educate me on the basics. Good thing, since most are poor teachers, and few are experts in particular rare conditions.

- So I became an expert in my own condition (I am co-author on this paper). This is especially important in cases like mine when the condition (papillary kidney cancer) has no standard of care and the only alternative is a clinical trial.

How important is it to have a caregiver?

It’s good to have someone you can trust who is looking out for you. My wife was there to help with insurance, driving, contacts with her brother, and always injected positivity in the situation.

Personalized medicine

In my case, personalized medicine proceeds in two steps.

In the first step, a doctor extracts my kidney tumor cells and sequences them to understand how they differ from normal kidney cells. These differences are called “mutations.” In the second step, the doctor prescribes a particular medication based on the mutation.

When explaining this to others, I note two things. The first, outlined in this JAMA article on lung cancer, is that sequencing has outpaced drug offerings. If each mutation points to a slot in a drug cabinet, only 10% of the drug cabinet’s shelves are filled.

The second is that although the theory behind precision medicine is clear, the understanding clearly has some holes in it. For example, as pointed out by Siddhartha Mukherjee in his NY Times article (June 2018):

‘In one landmark study published in 2015, 122 patients with several different types of cancer — lung, colon, thyroid — were found to have the same mutation in common, and thus treated with the same drug, vemurafenib.

The drug worked in some cancers — there was a 42 percent response rate in lung cancer — but not at all in others: Colon cancers had a 0-percent response rate.’

What is your hope for rare cancers like papillary renal cell carcinoma?

In my disease (papillary kidney cancer), there has been no increase in overall survival for the past 11 years. One barrier is getting enough patient information to study. However, new efforts such as Count Me In are forming, which allow patients to donate their information.

My hope is that this pan-cancer open clinical information movement, like the open software movement before it, will provide a productive alternative to the current ‘money-centered’ approach.

Especially for the research of rare diseases.

Inspired by Bill's story?

Share your story, too!

Papillary Renal Cell Carcinoma Stories

Bill P., Papillary Renal Cell Carcinoma, Stage 3, Type 1

Symptoms: Kidney stone, lower back pain, sore/stiff leg, deep vein thrombosis (DVT) blood clot

Treatment: Nephrectomy (surgical removal of kidney and ureter)

...

Laura E., Type 2 Kidney Cancer (Papillary Renal Cell Carcinoma), Stage 4

Symptoms: Profound fatigue, hypertension, high red blood cell count, severe back pain, badly swollen legs

Treatment: Chemotherapy (Cabometyx (cabozantinib) assigned under S1500 PAPMET clinical trial)

...