Burt’s Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumor (pNET) & Kidney Cancer Story

After experiencing brain fog and being completely out of it, Burt went to the hospital. They found out he had bad internal bleeding from ulcers. Doctors subsequently discovered a double diagnosis of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor (pNET) and kidney cancer.

Burt shares his nightmare hospital experience where he almost bled out on the table, how he found out and processed his diagnosis, and how he strives to make sure cancer never defines him.

This interview has been edited for clarity. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider for treatment decisions.

- Name: Burt R.

- Diagnosis:

- Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor (pNET)

- Kidney cancer

- Initial Symptoms:

- None; found the cancers during CAT scans for internal bleeding due to ulcers

- Treatment:

- Chemotherapy: CapTem (capecitabine + temozolomide)

- Surgery: distal pancreatectomy (to be scheduled)

I’m not thankful I have cancer, but there [are] so many silver linings and I’m so grateful for all that I’ve learned because I have cancer.

I’m not a cancer patient. The disease will never define me.

Introduction

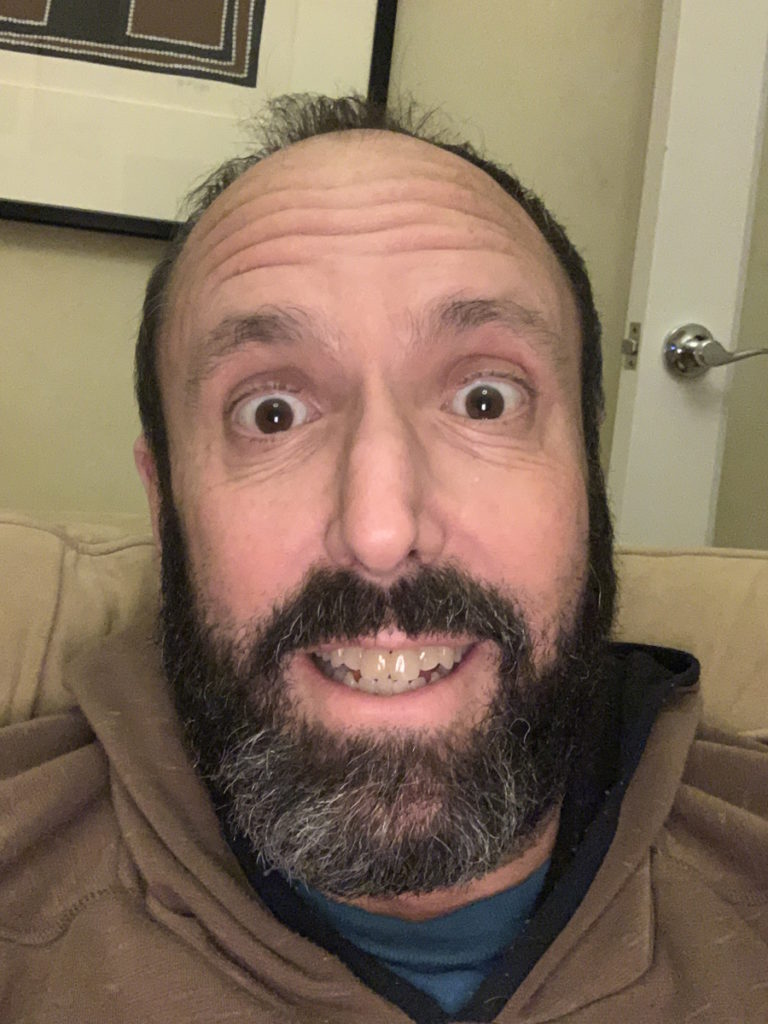

I consider myself a person first. I will never refer to myself as a cancer patient. I never refer to myself as the type of cancer I have. I’m always Burt who happens to have cancer. That’s the way I refer to myself because I never want the disease to define me.

I’m a native New Yorker. Moved to LA, San Francisco, back to New York, Connecticut, and then, ultimately, ended up in Portland, Oregon.

I’m married [with] two kids — one who works for a company in Redlands, California, and a daughter who’s a senior in California.

I love living in Oregon. It’s such a beautiful place and I love the outdoors. I walk outside a lot. I hike a lot.

I love talking to people. I’m an extrovert so I try to go out and meet people. I have a lot of coffee or Zoom meetings.

Once I got my diagnosis, I became a lot more driven to make a difference in the world. I do a lot of volunteering. There’s an organization called Catchafire, [which matches] nonprofits with specific project needs, with people who want to volunteer time.

I’ve met a lot of nonprofits that way. [I’m] involved with my own hospital. I’m also working with the group called NETCancerAwareness.org; I’m on their advisory board. I’m also on the Patient Advocacy Committee for the Society for Integrative Oncology.

I like to experience new things.

I’m not thankful I have cancer, but there [are] so many silver linings and I’m so grateful for all that I’ve learned because I have cancer.

I did a bucket list. I’m going to try to do stuff that I haven’t done before because I really want to, not because I’m worried about dying.

I don’t plan on dying. I’m going to live for a really long time and die with cancer, as we say, not from cancer. It’s helped me crystallize what’s important to me and some of the things that are important to me are doing new things.

I’ve never gone to Bryce or Zion or any of the big national parks on the West Coast. I’d love to go to Yosemite and climb Half Dome and do stuff like that.

Pre-diagnosis

Initial symptoms

I have chronic Lyme disease and I was in treatment for a long time. I have had a rough couple of years work-wise. I was laid off twice in three years and both jobs were ridiculously stressful.

[For] one, I had flown 71,000 miles in a year by June 1st. I don’t mind travel, but I don’t want to be on planes nonstop so that was extremely stressful and really took a toll on my body and my mind.

The one after was just highly political. I had somebody I worked for that didn’t go well and wasn’t respected by him. He thought he was a great marketer and he wasn’t.

I got laid off from the second job in June of ’21 and my health just started to decline. I wasn’t feeling myself anymore.

As time went on, I started to develop more brain fog. I flew to a conference in Boston and I basically couldn’t think. I couldn’t write a text, I couldn’t write an email, I couldn’t order food. I would lose my phone, which is something I’ve never done before. I wasn’t myself. I was completely out of it.

I talked to my wife and my sister and they both said, “Get on the next flight back home. Don’t stay anymore. Just come home.”

I believe in holistic medicine so I’ve been seeing a naturopath for 14 years. I came home, we went to him, and he helped bring me out of the brain fog. He helped clear my brain.

In June, I started to regress. Finally, right around July 1st, my wife looked at me and said, “We’re not going through this anymore. We’re going to go to a hospital and make sure there’s nothing seriously wrong with you.”

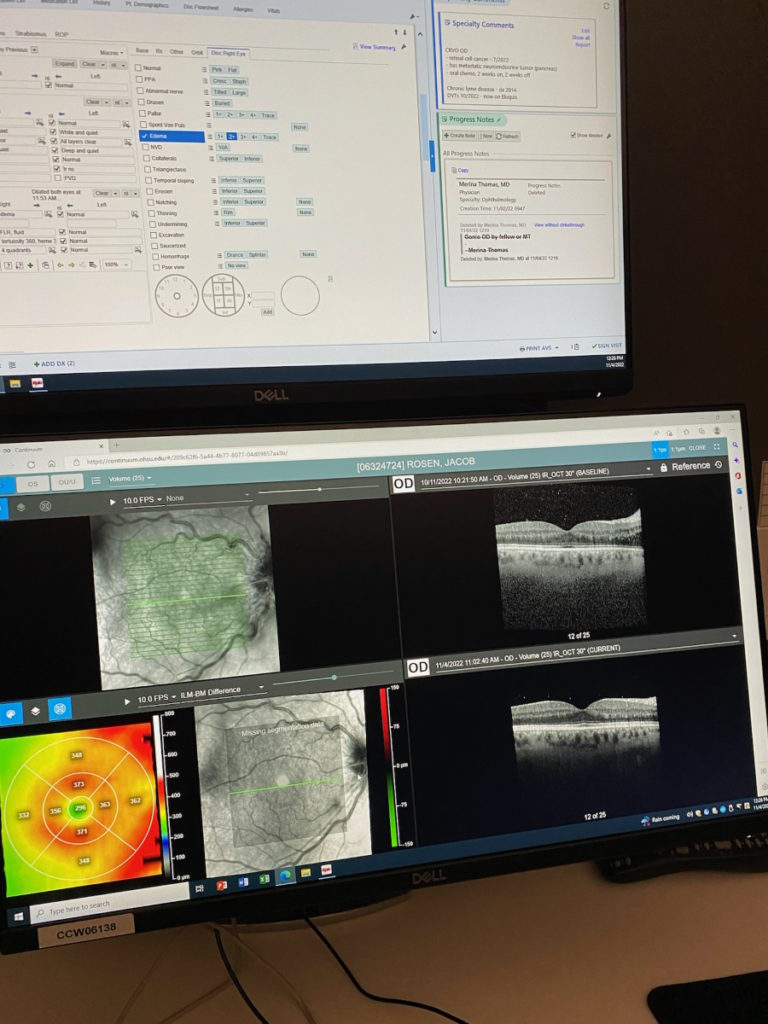

We went to the hospital. It turned out I had bad internal bleeding from two ulcers, one in my small intestine. Had a bunch of tests done. They found out I had cancer when they were doing CAT scans for internal bleeding.

We said we’re putting cancer on hold because [with] internal bleeding, I could die today. [With] cancer, there’s time. About 8-9 days [later], finally got that under control through interventional radiology. As I started to heal, we turned our attention to oncology.

I wasn’t admitted because of cancer symptoms. I was admitted because of other things I had going on. I’m holistic so I believe I’m a box. Burt is a box and all the stuff is connected. You can’t tell me the ulcers aren’t connected to the fact that I have cancer in my GI tract. It’s all connected.

The hospitals and the doctors won’t say it is because they don’t understand how. They’ll never say it’s connected because they can’t explain it. I got admitted for things that wouldn’t be classified as cancer-related symptoms, but they found cancer and those symptoms.

When you can’t think and you can’t control your thoughts, it’s terrifying. When you’re aware that you can’t, it’s terrifying.

The brain fog was terrifying. And brain fog is a Lyme disease so I actually thought it was Lyme.

I was supposed to start seeing a new Lyme doctor. I hadn’t even had my first appointment with her yet. I called her, crying, and just saying, “Help me. This is the scariest thing I’ve ever gone through.” When you can’t think and you can’t control your thoughts, it’s terrifying. When you’re aware that you can’t, it’s terrifying.

My Lyme doctor said, “Next time that happens, you immediately walk yourself into an emergency room and say, ‘I think I’m having a stroke.’ I don’t think you had a stroke. I think you have what’s called a TIA (transient ischemic attack).”

It was really, really scary. I’m not great when I’m not in control. I’m not a control freak but not having some level of control is hard for me. It was terrifying. It was sad, but sad doesn’t even really enter your consciousness when it’s like, “What’s going on in my head?”

When I checked into the hospital in early July I had an upper endoscopy. The doctor didn’t do anything wrong, but I think the scope hit my abdominal wall and started bleeding, [flooding] my whole cavity. I almost died on the table from an upper endoscopy. I almost bled out on the table. They had to intubate me.

There’s a lot of scary stuff that I’ve gone through. That being said, I feel amazing. I probably feel more myself than I have in years. I give myself what I call a Burtness scale, which is how much I feel like Burt, where a 10 is I feel exactly like myself and nothing’s wrong whatsoever. I’m pretty high on my Burtness scale lately.

I really feel great. I have two cancers, but I feel great and it doesn’t stop me from doing anything. I drive. I’m self-sufficient. I volunteer for three organizations. I hike. I go to yoga.

Diagnosis

My wife and I phrased it as phase one and phase two — phase one was stop the bleeding and phase two was cancer. Once the bleeding got under control and I was stable, then we started to deal with cancer.

Despite the fact that I said I’ll deal with cancer later, as soon as I heard that I had cancer, I would wake up at three in the morning thinking, Oh shit. am I going to die? If I die, where do I want to die? Who do I want around? I would start crying. I actually have an image in my head of where I wanted to be when I was going to die and it was pretty wild.

I’m not going to die. I can’t be more clear. I will not die from this. Barring anything I don’t know that’s about to take away everything I’m capable of doing, it’s not even in my consideration yet.

I really feel great. I have two cancers, but I feel great and it doesn’t stop me from doing anything.

Getting the official diagnosis

[During] the first three or four days in the hospital, I was mostly non-coherent because of the brain fog, which turned out to be an ammonia buildup in my brain because I was having liver function issues. They cleared that up and put me on meds that actually helped a ton.

I was in and out of coherence. The day after I had that upper endoscopy, I was coherent enough. The GI doctor came in and he was talking to my wife. At one point, he looked at my wife and whispered, “He knows he has cancer, right?” I didn’t and that’s how I found out.

First of all, there’s no ideal way to hear. Second of all, I refer to cancer as the most successful unintentional marketing ever. You say you have cancer, everybody thinks you’re going to die. There [are] so many things associated with the word cancer that may or may not be true.

I have two types — one is kidney cancer, which can [be] removed by surgery, and the other, I’ll have for the rest of my life. But there are people who have lived 20 years with it or even more and don’t die from it but die from other stuff. Cancer doesn’t terrify me. Actually, not at all. But that’s how I heard.

Cancer doesn’t terrify me. Actually, not at all.

Reaction to the diagnosis

The first question is, “Am I going to die?” The second question is, “When am I going to die?” And I was asking a GI who’s not even an oncologist. I think he was trying to figure out, How do I answer his questions but not answer his questions?

He answered them, which he probably shouldn’t have, but I don’t think he knew what to do. It was a really tough position for him. He’s not used to telling people they have cancer unless it’s a polyp that they removed from a colon.

The first question I had in my head [goes] towards mortality because that’s honestly what we’ve all been conditioned to think. It’s not like, “Oh, you have cancer. That’s a chronic illness, like ulcerative colitis,” People think, “Oh, you have cancer? Death.”

I use my blog for my own therapy. I wrote a post about how the biggest struggle for me was people, that when I told them I had cancer, who would say, “I’m so sorry.” Don’t be sorry. I’m fine. I’m not sorry for myself. If you want to feel sorry for me, that’s up to you. Just don’t do it in front of me because I don’t need it.

How other people react to the diagnosis

I wrote this whole article [about] the pity load, [which is] all about removing the pity load from people who are trying to figure out how to react to your bad news.

People want to be helpful, which is nice. But I appreciate it when they’re helpful because they know me and they want to be helpful in a way that’s going to help me.

I got home [from] the hospital and people kept saying, “Do you want us to bring over dinner or do you want us to do meal trains?” It was like, “No, thanks, I’m fine. I get up and cook three meals a day for myself. I don’t need a meal train.”

The “I’m so sorry” was another one. Prayers drive me crazy. I’m an atheist. I don’t believe in God. If you want to pray for me, do it for yourself. It won’t hurt. It can’t hurt, but I’m not excited. There [are] some things like that that are actually slightly annoying to me.

When I talk to people and tell people I have cancer, they’ll say to me, “How are you?” I’ll say, “I’ll tell you, but you can’t tell me you feel sorry for me.” My goal is to remove that conversation from them so they don’t have to feel the whole time, “What do I say?”

I was talking to a friend and she said, “How are you?” I gave her that speech and she said, “That’s fine. I won’t tell you I’m sorry for you.” I went through it. We had a great conversation.

She comes from the health insurance industry and she said, “I know health insurance can be a bear with stuff like this. If you want me to go through all your insurance stuff and see how I can help, negotiate with the insurance company to become a patient advocate, [or] whatever you want, that would be amazing. I’d be happy to do it.”

People want to be helpful, which is nice. But I appreciate it when they’re helpful because they know me and they want to be helpful in a way that’s going to help me.

To me, that was amazing because she understood what I was going through. She was empathetic enough to say, “Let me help you with what you’re going through.” It was like she understood my situation and knew what people in my situation needed and she responded based on that.

When I got home from the hospital, one of my cousins gave me a subscription to MasterClass. That is a genius gift for somebody who is basically really weak, somewhat bedridden, and can’t do a lot early on. It’s just so smart. It gives me something else to do.

People who are actually thoughtful enough to think about who you are and what you might like or what might help you and respond, that’s worth its weight in gold.

The generic stuff, it’s fine. If somebody says, “I’m so sorry for you,” it’s like, “Thanks?”

If you say to me, “I’m so sorry for you. Tell me more about what you have. Are you worried about it? Can you sleep at night? How’s the impact on your family?” That’s a whole different thing. That’s great, too.

People who are actually thoughtful enough to think about who you are and what you might like or what might help you and respond, that’s worth its weight in gold.

Treatment

I was in the hospital for two weeks. It was really about stopping the bleeding and getting me stable.

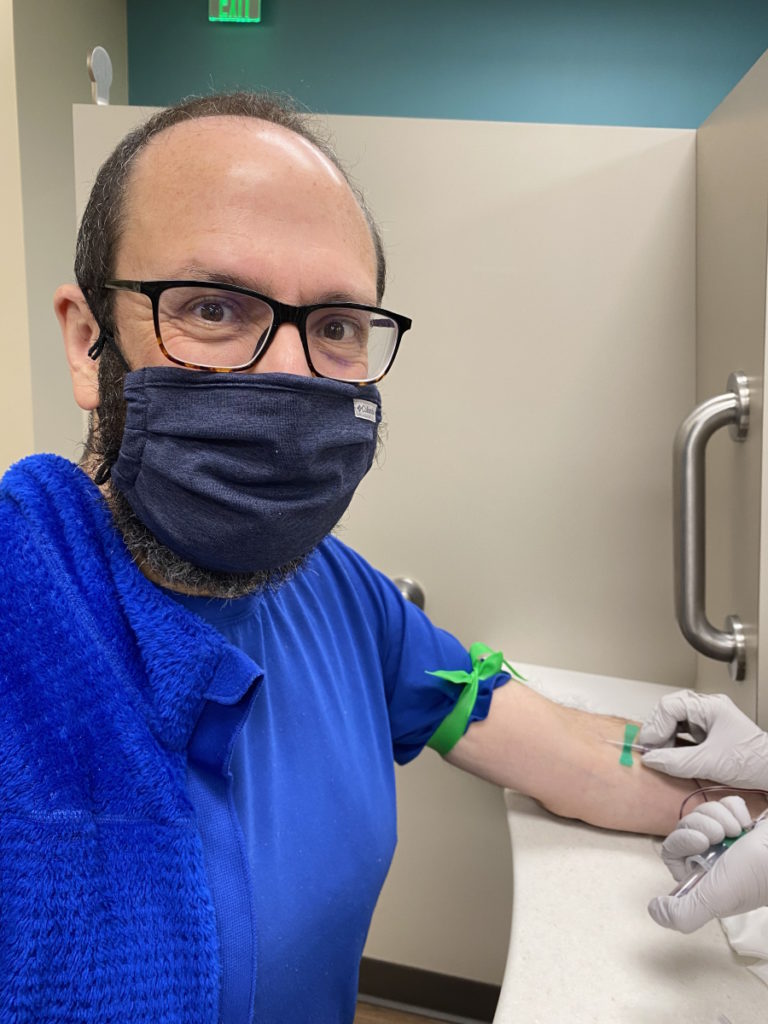

I did have biopsies taken of my kidney and my liver while I was in the hospital, but it was basically a side procedure.

I was at a hospital part of the Providence health system so they set up an appointment for me with one of their oncologists.

My wife and I both come [from] business backgrounds. While in the hospital, we made two lists [with] criteria that [are] important to us in a cancer doctor and then who we want to ask for recommendations.

It turned out that one of my better friends is a radiation oncologist so he obviously knows people all over the place. Then I’m also good friends with somebody who runs a research lab at Oregon Health & Science University, a major hospital in Portland.

We reached out to the two of them first. I had [an] appointment at Providence and they both said OHSU is great.

My friend who works there set me up with the head of the pancreatic cancer unit. I don’t have pancreatic cancer, but I have an offshoot. He met with me and we really liked their approach.

I like the fact that it’s a teaching hospital. They’re internationally recognized. The surgeon is one of those godfathers of the type of cancer I have. And so we started going there.

I’m really well connected in the healthcare community because of the time I spent in healthcare marketing so I had a million people to ask. I was really happy, honestly, with the second person I found, which was the OHSU people.

Providence was really good, too, but I had heard there was some turmoil in the hospital. There were some people leaving and they were getting some new people. They actually ended up getting a really, really good oncologist who specializes in pNET, but I was already at OHSU. It turns out, my medical oncologist at OHSU and the Providence NET doctor are friends.

Treatment plan

They got me on a protocol called CapTem, which is two meds. One is called capecitabine and one is called temozolomide. You also take Zofran for nausea when you take the temozolomide. It’s the same protocol that I’m on now.

The protocol is 28-day cycles. You have 14 days on capecitabine. [In] the last five of those days, you add the temozolomide so you’re on two drugs for the last five days and take the anti-nausea when you take the temozolomide. Then you go two weeks off of any chemo drugs.

That’s the only oncology protocol I’m on. In addition to that, I’m trying to go to yoga twice a week. I eat really, really well. I’m trying to exercise more, although it’s been tough. I’m trying to be active as much as I can.

I found that my mental health is the key to my physical health. If my mind is engaged and I’m feeling useful, valuable, and using creativity, I feel better overall.

I go to two naturopaths. Western medicine is more about, “How do we kill cancer?” The naturopaths will be more about, “How do we take care of your body to make sure it’s capable of killing cancer?”

My naturopath is the only one who’s actually said to me, “We have to figure out why tumors even grow inside you.” That’s not a conversation you ever have with an oncologist.

We don’t know yet. I know I don’t have any genetic stuff. I’ve been tested for that and I don’t show any mutations that would lead to cancer. There’s some other genetic testing I want to do, but I’m not sure I have enough tissue samples so we’ll see.

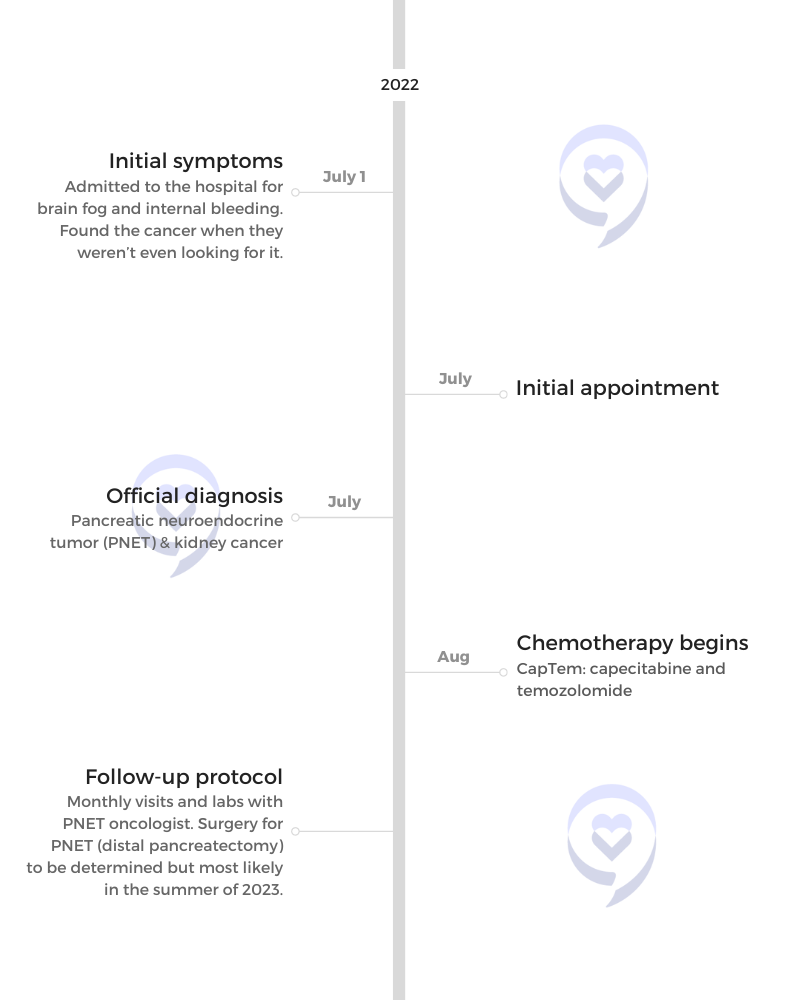

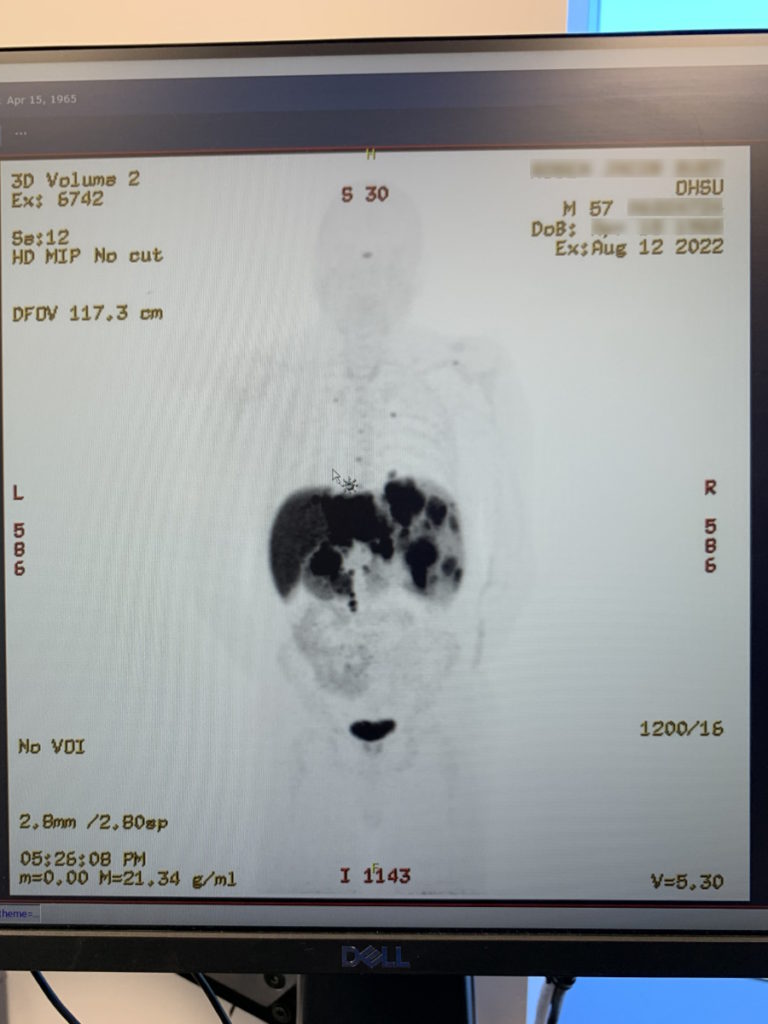

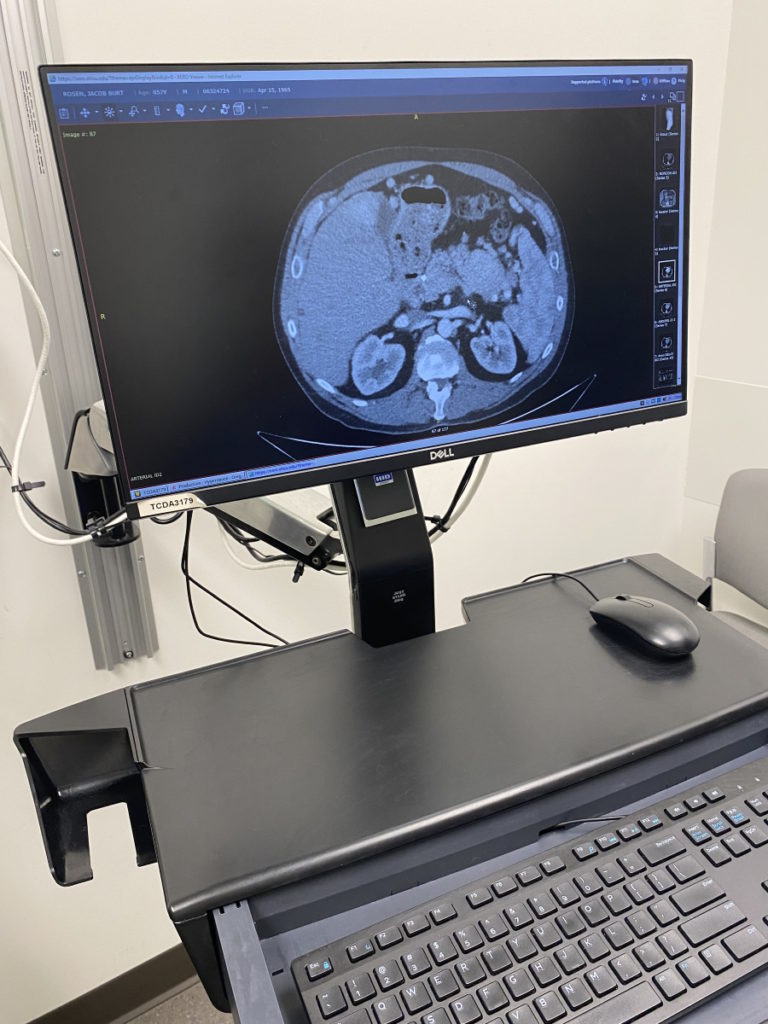

The pNET’s the priority because it’s already metastasized. I have it in my liver, some lymph nodes, and some other places.

The kidney cancer, everybody’s basically said that’s your second priority so we’re not going to worry about that yet. The only way to deal with kidney cancer really is through surgery. My chemo protocol is systemic so it would make sense that it would shrink the tumors and it’s shrinking the tumors in my kidney, too.

The surgery scares me. Having cancer doesn’t scare me. The surgery I’m going to have to have is a huge surgery and that scares the hell out of me. Hopefully, they can do the kidney part as part of that surgery. If they can’t, then I’ll have to probably have a separate procedure for the kidney.

If my mind is engaged and I’m feeling useful, valuable, and using creativity, I feel better overall.

Side effects from treatment

The protocol is considered pretty mild and most people don’t have a lot of side effects from it.

The way I look at it is I have symptoms from cancer. My main symptoms are GI stuff, fatigue, which is fairly common, [and] some skin issues. Those are the biggest ones. I have a little bit of brain fog on occasion, but it’s really married to fatigue.

When the chemo impacts me, what I refer to as a side effect is it makes those worse. It’s not like I take the chemo and I get heavily nauseous, get bad headaches, or get bad pain. None of that.

When I’m on chemo, my fatigue is worse. Even when I’m off chemo because I think it still accumulates in [my] body. I’m still able to function for the most part.

And it’s not consistent. It’s not like I can tell you day eight of every cycle, I’m going to get hit with something.

If I start to get more side effects, I feel like there [are] a lot of natural treatments and remedies. The Society for Integrative Oncology [has] published studies on acupuncture for pain management, music therapy, and other things that can help with some of those side effects. But, luckily, I haven’t had to do a lot of them.

Distal pancreatectomy for PNET

I currently have a 6.5-centimeter tumor on the tail of my pancreas. They’ll remove that part of my pancreas, my spleen, my gallbladder, and then since I have metastases in my liver — I think four or five tumors in the left lobe of my liver — they’ll remove the left lobe of my liver.

I do have some tumors [on] the right side, but they think they can just take those out. Supposedly, the right lobe of my liver has already grown a ton to accommodate for some of the function lost with the left lobe. My kidney functions both show fairly normal in all my blood tests.

I’m not excited. To me, losing organs is just such an unnatural solution. In 10 or 15 years, no one’s going to do this surgery anymore because it’ll be considered barbaric, but it’s what we have now.

My surgeon has told me it’s a serious surgery. He said, “You could be on the table for nine and a half hours. I’m going to be in constant conversation with the anesthesiologist about, ‘Do we think you can take more or are you losing too much blood? Do we need to close you up and have you come back in four months or can we get most of it out?’”

They won’t get 100% of the cancer out. Again, the kidney is different. They can get 100% of the kidney, I think.

[Regarding] the pNET, though, my surgeon has read studies where if you get 70% of it out, it’s as effective as getting 90% out. He feels like he can get out the primary tumor, which is the one on my pancreas, and a bunch of the other stuff.

He’s also said to me, “The liver is the most important thing for you. The liver decides if you live or die.” Basically.

He said our focus will be the liver and then if we can do everything we have to do in the liver, then we’ll remove the primary from your pancreas and then we’ll do the other stuff.

My goals moving forward are to heal myself, to help others heal, and then to help others who can help others heal.

How did your cancer treatment affect your mental health and emotional well-being?

When I got out of the hospital, I was really, really weak. Going from the couch to the bathroom, I couldn’t walk straight. I couldn’t do a lot. My wife, who’s unbelievable, was making [my] meals.

Early on, it was tough. It was depressing. I was just sitting there. I could do some MasterClass stuff. After a while, I could read a little bit and I’d watch a little bit of TV, but it just got depressing.

I have a lot of energy so I always have to be doing stuff. I can relax, but it’s hard for me to relax sometimes. As I started to get better, I just needed more challenges and the challenges tended to be more mental whether they were business problems, creative solutions to different things, or even blogging because that gave me a great outlet.

I started to look for those things. I’m Jewish. I’m not practicing but because of my upbringing, I remember when Yom Kippur is every year. This year, I couldn’t fast. I’ve always done it just because I like the concept of not focusing on food for a day. It’s pretty amazing if you haven’t done it.

I decided to go take a walk in the woods instead — no headphones, no music, [and] no podcasts. I decided that I wanted to organize myself.

I built my own strategic plan. My goals moving forward are to heal myself, to help others heal, and then to help others who can help others heal.

The first one is obviously just about me. The second one was about meeting as many patients as I could, helping both one on one and group, and volunteering. Then the third was a job specific to healthcare where I can make a difference in people’s lives.

Once I had those three guiding principles, that kind of organized me. I actually removed myself from stuff that wasn’t healthy and didn’t fit those principles. I resigned from a board that had nothing to do with helping other people.

I started to put different things in those buckets. Yoga has made me feel great in the past so I want to start doing yoga. I know it’s going to open my body more. It’s going to let things flow better. I started going to yoga twice a week.

I’d been in therapy for a while, but my therapist became more important because I was dealing with more serious issues in a lot of ways. I go to therapy once a week. I meditate most nights.

I got to the point [where] I decided there are going to be two parts to my healing — the drugs and “Let’s go kill the crap,” then “How do we make Burt healthy enough to survive killing the crap?”

A lot of people believe that while chemo might kill cancer, chemo kills you. And there’s a lot written on that stuff, too.

Part of it was just from boredom and from knowing that I needed more challenges and seeing how I felt as I undertook those challenges. Then the other part was the focus on doing things to help me get healthier in ways that weren’t just taking pills.

I don’t plan on dying. I’m going to live for a really long time and die with cancer, as we say, not from cancer.

Death and cancer

Unfortunately, there are cancers out there that will kill you and there’s nothing that science or anything can do to save you.

For others, look at mortality rates. The latest cancer numbers I might have seen is 50% of people with cancer pass away from cancer. So 50% don’t. The number of people who die from it will come down over time. It’s certainly not going to increase.

So much depends on the individual and on the type. That’s why I’m so upset when I say I have cancer and somebody says, “I’m so sorry.” Don’t pity me. I’m fine. Nobody needs to feel sorry for me.

It’s hard because, again, we also all have different personalities. I’m pretty optimistic and positive just by nature.

There are all these thoughts and emotions associated with the word cancer that don’t have to define you. I consider myself Burt who happens to have cancer, the same way I happen to have eczema or happen to have my legs itch.

Cancer is a higher degree of difficulty, no doubt. But that’s what I am. I’m not a cancer patient. The disease will never define me.

Death is hard, but there [are] a lot of people who have cancer who don’t die. And there [are] a lot of people who live a really long time with cancer, even if they ultimately end up losing to it.

Importance of a positive mindset

I’m very, very, very lucky and I’m very grateful. I know who I’m grateful for, but I don’t know who I’m thankful to.

I have an amazing support system. My wife is unbelievable. My medical team is great. My two naturopaths are both amazing. There’s a really strong community, even though it’s a kind of rare cancer that I have.

You have two choices. You can just sit around and wait or you can just say, “You know what? I have it.”

Sometimes I accuse myself of not dealing with the fact that I have it. I was in therapy and my therapist said, “What do you want to work on?” I said, “I think I need to get more in touch with myself emotionally. I have cancer. I have [what] a lot of people consider a deadly disease. I don’t really deal with it. I just ignore it and I go on and do other stuff.”

He said, “We could try to break all that stuff down, but it’s doing a lot of good for you right now. Those defense mechanisms are letting you feel good and it’s letting you do all these things. So for me to strip those things away from you right now, that’s not a good idea.”

Words of advice

The most important thing I’d say is you’re an individual. I can tell you what’s worked for me. You can read tons of articles about what’s worked for other people. It doesn’t matter. What matters is what works for you.

When you close your eyes and start thinking about what makes you happy or what you’ve done in the past that made you happiest, can you do those things more?

If you love quilting, even if you’re bedridden, can you quilt? Can you quilt more? Can you just start doing things like that?

I think what happens is as you start to take on more of those things, then you start to think about other things you’ve done. Maybe it’s quilting and cooking. Figure out what makes you happy and then just try to do some of those things. If you can’t always do them, maybe you can do things around them.

Even if you can’t quilt, maybe you can start watching YouTube videos of other people quilting. Maybe you can read books about people who quilted. Maybe you can study history through quilting.

Start with things that make you really excited. This is hard and I know people say this a lot, but it’s really important. You have to tune into yourself.

You’re an individual. I can tell you what’s worked for me… What matters is what works for you.

A lot of nights, before I go to bed, I will say to myself, just in my own head, “What else can I be doing to make myself feel better?” Sometimes I actually get answers back. Sometimes I don’t. Sometimes there’s nothing interesting.

It’s like, “Okay, that just tells me [to] stay the course. I’m doing fine.” There are other days like, “Yeah, you really should reach out to this person. I think it’ll help you a lot.”

I know that sounds a little wacky, but you know a lot more than you give yourself credit for. Looking inside and trying to find those things that get you excited and put a smile on your face are the places I would start.

You’re always going to be your own advocate. There’s no way to say this, but our healthcare system sucks. There are some decent people who work in it and there are some good people who work in it, but the system itself is horrible. If you don’t advocate for yourself, a lot of times, no one’s going to advocate for you.

I was bedridden in the hospital. If I got out of bed, the alarms would go off. My mom wanted to talk to me and my wife said, “Nice Burt has to go away. If you don’t feel up to it, you have to say, ‘Mom, I can’t talk now. I’ll call you tomorrow. Hopefully, I’ll feel better.’ You have to stop worrying about making other people happy.”

I’m a people pleaser. I always want other people to be happy. And I learned that early. You have to put yourself first. It doesn’t mean you can’t be sensitive to other people.

I went through [an] upper endoscopy. I almost died while having it. A couple of days later, they wanted to do another to see if the bleeding stopped and if the ulcers were getting better. I said no.

They said, “Why not?” I said, “My body can’t take it. I don’t want the procedures to cause my body more harm than whatever’s going on in my body.” They were generalists. I said no and they said, “Okay. It’s your call.”

The next day, the gastroenterologist came in. We told him the story and he said, “Yeah, I would never give you another one now. I wouldn’t do it either.” At the end of the day, you’re in control.

I know people who are 80 who have the type of cancer I have who refuse treatment, who say, “I’m getting close to where my life is probably going to move on anyway. I don’t want to put myself through that right now.”

You’re always in control of yourself and yet you have to be in control of yourself. Ask questions. Because at the end of the day, you’re the one who has to. You’re the one who this is supposed to help and you’re the one that this is going to hurt.

If you’re worried about something, don’t do something because the doctor says to. All the best doctors are used to having discussions.

At the end of the day, you’re in control… You’re always in control of yourself and yet you have to be in control of yourself.

Almost every time I’ve gone to my oncologist, I’ve said, “Hey, what about this procedure that I read about online?” I put the onus on him to explain to me why it won’t work.

That’s the one other piece of advice I would give. Three or four months in, I said to my doctor, “Can we have an appointment where we don’t talk about my test results at all? We’re going to be working together. We’re going to be partnering on this for a long time. Can we just talk?” And we did and it was amazing.

We talked about Twitter. He told me who he follows. He told me who his mentor was. We talked about some other doctors and what they were doing. I think we even talked a little bit about his kids.

If the doctor can’t spend the time, they’re going to say, “I’d love to. I wish I could stay longer, but I have to go to somebody else.”

You can say, “Great. So when can we follow up on some of the other questions I have?” Sometimes they’ll say send me an email or send me something through the messaging platform. Sometimes they’ll say set up another appointment, but don’t censor yourself.

The day of the doctor is god is gone. If you treat your doctor that way, it’s only going to hurt you. In the cancer world, everybody expects you to get a second opinion. A lot of them will recommend you do and even give you people to go talk to.

When you first get diagnosed, you think, Am I going to die? It doesn’t matter what type of cancer you’ve been diagnosed with. You have those thoughts and talking to other people who have those thoughts would be really valuable.

I do think there’s a lot of work in the cancer world to be done around understanding the experience and culture of actually having it.

I think there [are] really two parts to cancer — the treatment part and the experience part. The experience part is [what] people don’t ever focus on or talk about.

A lot of groups are about cancer treatment. The groups I haven’t found yet, which I’m trying to find, are, “I was just diagnosed last week with cancer, what do I do? Who do I talk to?” “How do I explain to my mom I have cancer?” “How do I explain to my brother [who] I haven’t talked to in 50 years that I have cancer?” Those groups don’t exist and the experience stuff needs a lot more focus than it gets.

The week I got diagnosed, I had more in common with somebody who was diagnosed with bladder cancer — something that I didn’t have, who had just found out about it — than I did with people who had had my condition for 15 years.

All the support groups and organizations are set up around [the] condition state and not experience with the condition. I think that’s a huge miss and a huge opportunity.

Be your own advocate and understand, at the end of the day, you’re in control of every decision. Your caregivers can tell you, “Here’s what I think.” You can still say to a caregiver, “Thank you for sharing your opinion, but I just don’t agree and I’m not going to do that.”

You’re in charge. It’s you. This is all about you. That’s the biggest thing I tell people.

Inspired by Burt's story?

Share your story, too!

Neuroendocrine Tumor Stories

Tabbie V., Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumor (pNET)

Symptoms: Abdominal pain, unusual organ "inflammation" feeling when walking, fatigue

Treatments: Chemotherapy (oral and IV), surgeries (Whipple procedure or pancreaticoduodenectomy, liver resection or partial hepatectomy)

...

Hayley O., Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumor (pNET)

Symptoms: Severe right-sided pelvic pain, nausea, diarrhea

Treatment: Surgery (pancreaticoduodenectomy or Whipple procedure)

...

Drea E., Gastric Neuroendocrine Tumor (gNET), Stage 3, Grade 1

Symptoms: Fainting spells, fatigue, dizziness, anemia, shortness of breath, absence of menstruation, unexplained weight loss, night sweats

Treatment: Surgery (total gastrectomy with a Roux-en-Y reconstruction)

...

Haley M., Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumor (pNET)

Symptom: Persistent digestive issues

Treatment: Surgery (pancreaticoduodenectomy or Whipple procedure)

...