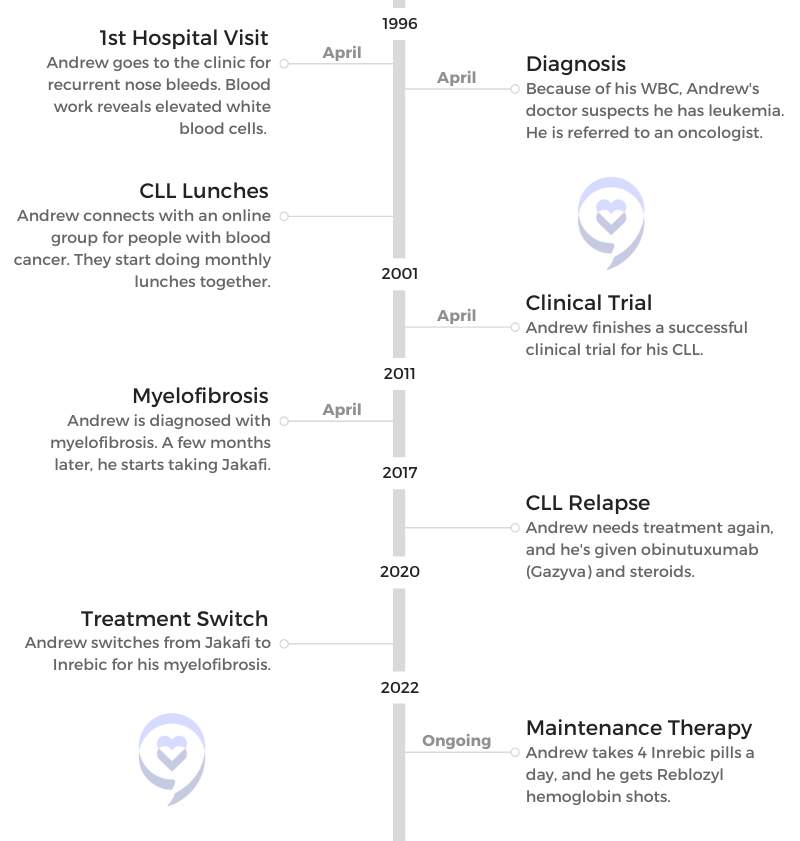

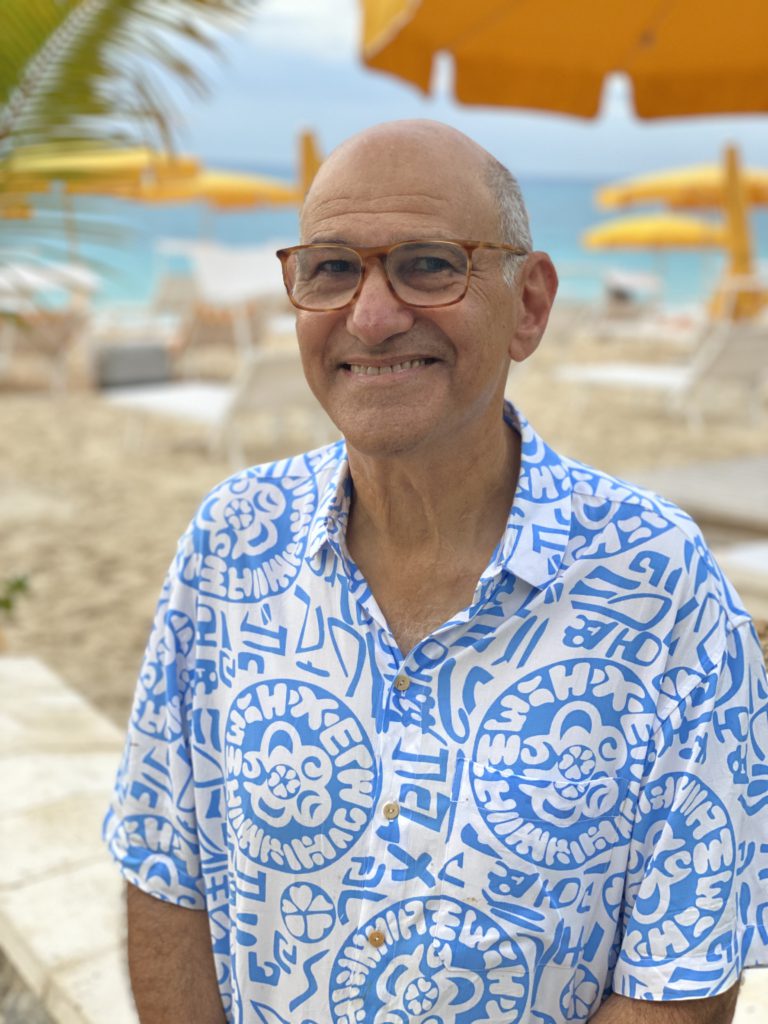

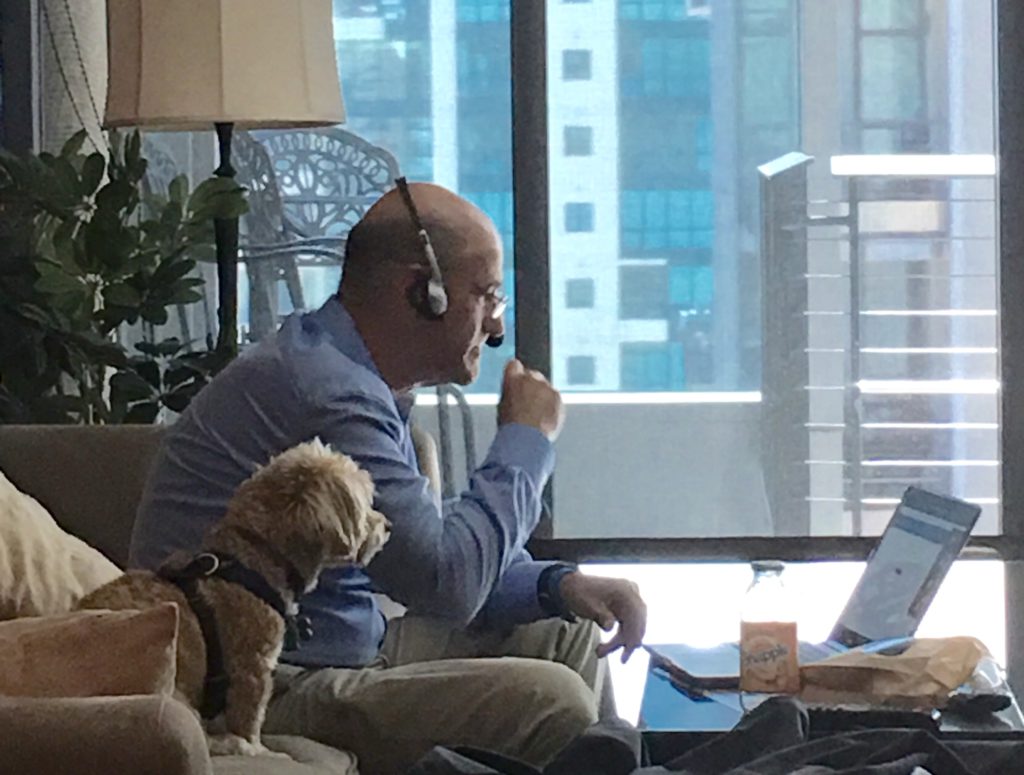

Andrew Schorr: My Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL) & Myelofibrosis Story

Andrew Schorr was a healthy runner with a wife and two young kids when a surprise cancer diagnosis changed his life: chronic lymphocytic leukemia, or CLL.

Andrew recounts learning and processing the CLL diagnosis, connecting with other CLL patients through online communities and in-person lunches and benefitting from 2 different clinical trials.

This was part of a series on The Patient Story called, “Cancer Friends,” featuring Andrew Schorr and Esther Schorr. The two co-founded PatientPower.info, a resource for other cancer patients and caregivers to help them through their diagnosis and treatment.

- Name: Andrew Schorr

- Diagnosis:

- Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)

- Myelofibrosis

- CLL treatment:

- 2001: Clinical trial

- 2017: Gazyva (obinutuzumab) and steroids

- Myelofibrosis Treatment:

- 2011 – 2020: Jakafi (ruxolitinib)

- 2020 – Current: Inrebic (fedratinib)

- 2022: Reblozyl (luspatercept)

Esther’s Caregiver Story

Esther shares her caregiver story, reflecting on lessons learned through her husband’s CLL diagnosis in 1996.

Andrew & Esther’s Story

Andrew and Esther share their CLL story, including reacting to a cancer diagnosis and figuring out their next steps together.

- How did you learn you had a blood cancer 26 years ago?

- The Importance of Community

- CLL lunches

- Clinical Trial

- Why did you decide to join a clinical trial?

- Signing the papers and starting

- Figuring out the logistics of collaboration between MD Anderson and your local HMO

- Clinical trial

- Phases in a clinical trial

- What were you thinking during this process?

- The importance of speaking up for yourself

- How did you get them to work together?

- Lessons about Living Life

- Going through Treatment Again

- DVT and Myelofibrosis Diagnoses

- Maintenance Therapy

This interview has been edited for clarity. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider for treatment decisions.

While I’d like to plan for next month, next year, 10 years from now, I don’t know if I have that. So today the answer’s yes.

Andrew Schorr

How did you learn you had a blood cancer 26 years ago?

Processing his CLL diagnosis

[My doctor said] If your white count is elevated and you have no reason like an infection, it could be leukemia.

Dun dun dun. You’re really shocked. The only thing I knew about leukemia was the solicitations for the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, typically with somebody knocking on your door and then showing you a picture of a little 4- or 5-year-old kid with acute leukemia.

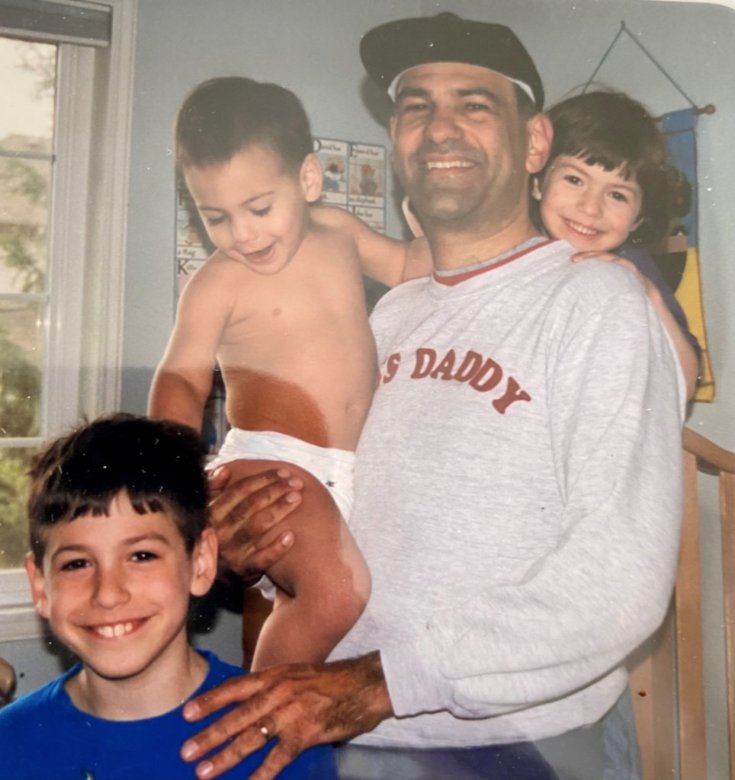

That’s all I knew. It wasn’t really clear whether leukemia was a cancer that could affect adults. I didn’t know any of that. He said, “I’m going to refer you to an oncologist.” It was a beautiful spring day, as I said, in the evening. Esther and I took a walk in the park. I was 45 years old. We had 2 small children.

I was thinking, “This is it. I’m not going to live very long.” Leukemia can be a fatal condition, and I thought, “Have I had a satisfying life? And leaving Esther with 2 kids. Oh, my God.” It was pretty tough.

»MORE: Patients share how they processed a cancer diagnosis

The Importance of Community

Connecting with other CLL patients

We reached out to a friend of ours, who was sort of a computer geek. Now, remember, this was 1996. There wasn’t a lot going on on personal computers then. Internet speed was really slow.

He came over on our little home computer, and he said, “There’s a news group for people with blood cancers. Maybe you should join and correspond with other people and find out more about this.” So I did.

The lady who ran this group was a woman named Barbara Lackritz, who was a school speech therapist outside Saint Louis and had chronic lymphocytic leukemia, which was the diagnosis I ended up receiving. I typed her a note, “We’re terrified. Can we call you?” We talked to her on the phone. Again, it was one of those spring nights.

Her famous words were, “Chill out. You’re not going to die anytime soon. There are certain doctors who specialize in this illness. My advice to you is to connect with them.”

That is what ended up happening. A couple of things there. One is you don’t know anything about leukemia. You don’t know anything about cancer. You feel your life is over and you don’t know anybody who has it.

Eventually I met other people in Seattle. We started having lunch together. We connected on the Internet and said, “Let’s do lunch.”

CLL lunches

Just to continue for a second, it became wonderful that even online, I knew I wasn’t alone. Esther, my wife, knew there were other spouses who dealt with this as well. In this little online world, very early in 1996, I said, “Hey, I’m in the Seattle area. Anybody else here?”

And, “Oh, I am.”

“I am.”

“I am.”

“I am.”

“Let’s do lunch.”

You go into a restaurant, and there are these people who look pretty normal. They don’t look like they’re at death’s door. You go over, and you say, “I’m Andrew.”

“I’m Gary.”

“I’m Carol.”

“I’m Frank.”

“I’m Susan.”

“I’m Pat.”

We all have a diagnosis of chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and some of them had had it for a while. We had different doctors. Some, I think we had the same doctor. It became very comforting. Then I think we started doing that monthly. Connecting with other patients was tremendous support.

Now, I will tell you, over time, we realized that chronic lymphocytic leukemia was not the same for all people. One person, Gary, had a transplant and ended up later passing away. Somebody else, Pat, who I’m still friends with years later, never had treatment.

Then I was in the middle, where eventually I did need treatment. I just think of us around the table and it became very real that there were other people who were dealing with the same condition. We had something in common, and we were willing to share.

What would you say to someone who has just been diagnosed?

The first thing I would say to particularly a new patient or a family member is the same thing that a veteran patient, Granny Barb Lackritz we called her, said to me, and that is, “Chill out.”

Even more so now, because the options in CLL for getting treatment that will be effective for a long, long time with others coming is very real. I think there’s a tremendous time of hope for all of us and it’s working. That’s part 1.

Part 2 is that one person’s story may not be your story. It can be very individualized. There can be different genetic, genomic differences that make your situation different. You may have other illnesses that affect overall how you’re doing.

That’s why it’s so important to get personalized care. If you do, for the CLL, there are some very effective options. If one of them peters out on you, there’s something else. I think it’s a very hopeful time.

Clinical Trial

Why did you decide to join a clinical trial?

I knew nothing about clinical trials and I would say I was at the starting point [like] many people. They say, “I don’t know if I want to be a guinea pig. What are they going to do to me? Will it really benefit me? Could it benefit others, etc.?” I just wanted to get well.

However, I had already connected then with a world-famous leading leukemia department at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston and one of the leaders in the field, a fellow named Michael Keating. When he recommended to me that there was a clinical trial that they were doing, they were the only site in the world adding a targeted therapy, a non-chemo drug to the existing chemotherapies.

They’d already had some experience with it with sicker patients, but they felt it could work for patients who weren’t sick, who were newly diagnosed, had no treatment and that it could do even better. I thought about it, and by then I was starting to develop symptoms after 4 years: swollen lymph nodes and large spleen, fatigue, etc.

There were other trials going on at the same time, including in Boston for a bone marrow transplant. In a bone marrow transplant, you’re kind of out of pocket for the better part of a year. With this other treatment, I was going to be able to continue to work most of the time, so that sounded more appealing than the bone marrow transplant.

»MORE: Learn more about the process of clinical trials from one program director

Signing the papers and starting

I should mention that eventually the bone marrow transplant trial was stopped, but I’d already made the decision to go this other direction. So what did I do? Again, I went back to where I’d been at the time of diagnosis, and that is to connect with other patients. I went online.

“Hey, does anybody know anything about this clinical trial?”

This person in Texas, because it was MD Anderson, said, “I’m a schoolteacher. I’m on that trial.”

“I do roofing. I’m on that trial.”

“Can I talk to you on the phone?”

I did, and I said, “Are you glad you’re in it? Are you glad you’re doing it?” They all were. That patient-to-patient connection gave me some confidence, and [with] the leading scientist doctor, I had to say yes.

It’s scary when you do it because they give you a whole bunch of papers to sign. There were some patients who died very early in the trial, so there was this big black box: “You could die,” basically. Lots of legalistic stuff.

You have the doctor, you have the research coordinator, you have the research nurse, all these people in white coats. My wife, Esther, and I were sitting there. “Sign here.” And we did.

We said, “Okay, when does this start?”

They said, “In about 4 hours. You’re going to that unit, and you’re going to get an infusion.” That’s what happened. I started right away, and that was 6 months of treatment.

Figuring out the logistics of collaboration between MD Anderson and your local HMO

First of all, when I saw the second opinion at MD Anderson, my HMO doctor was not in favor. He said, “We’re not going to pay for you to go to Houston, Texas, from Seattle. They’re going to say the same thing and that is, ‘Start chemotherapy now.'”

I said, “No disrespect to you, but this is my life on the line. I’m going to go even at my own expense.” And I did.

The Houston expert said, “No disrespect for your HMO doctor, but you don’t need treatment yet. When you do, I’ll probably have a clinical trial that would be an option for you and we’ll discuss that. Go home.”

I should also mention that the “go home” was because we had thought of having a third child. He said, “Go have your baby,” which we did. There was a disconnect between the HMO doctor back in Seattle.

I went back to Seattle, and I said, “Dr. Keating says, ‘Wait,'”

“Okay.”

“And that maybe there’ll be a clinical trial.”

“Well, okay. Let’s see.”

I let Houston drive the bus, and the HMO doctor just nodded his head. What happened? We had to work out the logistics. When I needed treatment — swollen lymph node, enlarged spleen, fatigue, etc. — the trial was ready.

Clinical trial

We had 2 little kids, so Grandma and Grandpa, friends, aunts, uncles [helped]. Esther and I were going to be in Houston for at least a week. When you have little kids, that’s a lot of juggling to do. But we pulled it off, went down there, stayed in a little hotel that MD Anderson has across from the clinic, and then got the treatment as an outpatient. That worked out.

As far as expense goes, we paid for the travel, but that seemed like a small expense for the benefit it was going to get. Otherwise, I believe that the care was covered by what insurance I had. We had to pay for travel and work out the family logistics. It was an adventure.

The trial, I fainted the first night from IV Benadryl. That was an experience — the nurses giving me smelling salts, and I hit my head on a bar when I fell. My mouth was bleeding. That first infusion took about 8-and-a-half hours. It was on the final night — we were watching TV in the little room — of the TV show “Survivor.” I was feeling like a survivor on the island.

Then Esther wheeled me back to the hotel across the way in a wheelchair at like 3 in the morning. The trial worked out and it ended up with a 17-year remission, so I’m very grateful for that.

Phases in a clinical trial

Phase 1 is typically first in humans. That doesn’t mean they weren’t testing it in the lab on animals, etc., but first in humans. Often that’s with the very sickest people, where they’re sort of out of options often and that’s a phase 1 trial.

Phase 2, they have it pretty well figured out. Now there’s a larger group, maybe 100 people or more. They’re working. They’re tweaking the dosage. They’re really monitoring for safety, looking for any side effects, anything like that. Fortunately, I didn’t. I had nausea, but I was able to continue the treatment’s 6 cycles.

Then a phase 3 trial often goes worldwide. Now it’s on hundreds and hundreds of people as they’re really getting further data, and they’re looking for little signals of whether side effects or what they call adverse events (things that they don’t want to have to happen) show up.

What happened is that I got this combination therapy known as FCR (fludarabine-cyclophosphamide), 2 chemo drugs, and a targeted monoclonal antibody, rituximab. I was like patient number 70 and I got that combination 10 years before it was approved as a combination by the FDA.

Now, would I have been alive had I just had chemo and not had this Rituxan added and been in this trial? I don’t know. For me, it provided a real advantage and a head start on state-of-the art treatment. I’m very grateful for that. I think it saved my life.

What were you thinking during this process?

There are a few lessons in what I’ve been through. One is that you need to identify a knowledgeable health care team. Ideally, if you believe that medicine moves forward, you need through them — or maybe even additional resources — a window into what could be next or better for what you have.

Then you need to consider, if it’s not approved medicines, is there something that’s experimental in a clinical trial that could potentially offer you an advantage? That was the decision I made, that the traditional approach was not great. It was pretty toxic and did not cause a long remission.

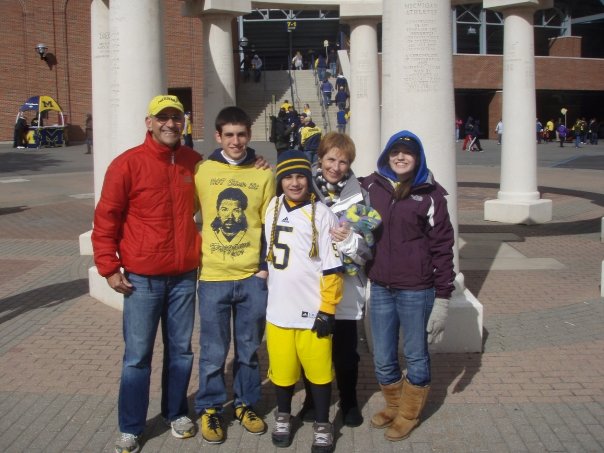

I was 45 years old and then at the time of the trial, 49. I wanted to have a long life. I’m 71.5 now, so obviously it made a big difference. I think you have to really think about your future with people you trust and that’s what I did. It ended up being the right decision, for which I’m very grateful also.

We went ahead and had the hug from our doctor. Keating hugged Esther and said, “Go have a third child. You’re going to be around a long time.” That kid’s 25 years old now. It’s given us a lot of joy. He’s been a kid, so [there were] ups and downs, but we never would have had him. Every time I see my son, that’s a sign of the gift I was given by modern medicine.

The importance of speaking up for yourself

I think you need to be respectful of the doctors and nurses you’re dealing with, but recognize that they may have a lot on their plate. My HMO doctor was tasked with treating every cancer that any member of the HMO would have, with leukemia maybe not being high on the list.

Breast cancer, colon cancer, lung cancer be much higher. He really had spent a lot of time being up on that. Was he necessarily up or totally informed of the latest research for what I had? Maybe not so much.

I, in a respectful way, said, “I know you’re a very devoted doctor, but I want to go the extra mile.”

He said, “We’re not going to pay for you to go get a second opinion, but it’s your right.”

Well, guess what happened? I was eventually in the clinical trial, which was coordinated by MD Anderson Houston and the HMO clinic in Seattle, where I lived. I got them to work together.

How did you get them to work together?

By saying, “Here’s a world-famous doctor in Houston. He signed me up for this clinical trial. You have the medicines available in Seattle. Will you kind of play ball?” They said they would.

I got the remission, and I went back to see my doctor for a check-up in Seattle. I said, “How are you treating other patients now with CLL?”

He said, “Andrew, the same way you got treated because I, as an HMO doctor, learned from your experience being in the trial.”

Lessons about Living Life

What was it like going from the clinical trial back to normal life?

I think the word that applies then but applies every day is “uncertainty.” You don’t know if another shoe is going to drop, either from the medicines you had or from the illness that’s not cured, because it wasn’t cured. It was knocked back. I was in remission.

I would develop a cold, and I realized this pattern over time that it always led to a sinus infection. Then, even though they hesitate to use antibiotics broadly, I always needed an antibiotic and maybe a second course.

You begin to see a pattern of life after treatment. You try to take control of it with your local doctor, and so we did. As a cancer survivor, you’re always concerned is that ache and pain — or that cough you have or whatever — the sign of something more serious?

In the case of CLL, what you’d worry about would be getting pneumonia, which could be fatal. That’s what people with CLL die of: an infection that your body can’t fight off. You have to stay ahead of that. If you have a cough, “Oh, my God, is it leading to pneumonia? Should I call the doctor right away?” You have to take responsibility for that as a patient.

Always saying yes

But that said, the days you feel good, go for it. One thing I’d say about life after treatment is when people invite Esther or me for something or together, invariably I feel the answer’s yes. Do you want to go out to dinner? Yes. Do you want to come to a show with us? Yes. Do you want to go on a bike ride with us? Yes.

Why? Because that’s what life’s about. While I’d like to plan for next month, next year, 10 years from now, I don’t know if I have that. So today the answer answer’s yes.

What guidance do you have for people?

First of all, I’ll mention something about social media. Often the people who post on social media have some more urgent, serious concern. I didn’t post anything.

I just went on with my life and CLL faded in the rearview mirror. I knew I still had it, but it wasn’t affecting my life. I think as you go on, or if you’re in watch and wait but you have no active symptoms that are affecting you, just go on with your life. Yes, you may hear about somebody who has some issue, but today most of these issues can be treated effectively.

If you have the right knowledgeable health care team, that’s part of your responsibility to secure that team. But if you do have the right team, then if you’re in watch and wait or you’re in remission, I think it’s about, “Go do what you want to do.”

Going through Treatment Again

Why did you have to get treatment again in 2017?

I knew that I was not what they call MRD negative, or minimal residual disease or measurable residual disease negative. One of my friends, Dr. Wierda at MD Anderson, had done a test, and he said, “It’s going to come back sometime. It’s going to show up.”

I had that in the back of my mind. Then here in San Diego with monitoring from my doctor here, Dr. Kipps, we could see the white blood count go like that. It did come back. I wasn’t shocked that it happened.

Then okay, it worked before. What do we do now? It wasn’t the same treatment. It was sort of more modernized treatment. And guess what? That was in 2017. We’re in 2022, and the CLL has not been a factor after going through those cycles of that treatment.

My pattern of CLL is to know that it’s there, that it could raise its head again. We’ve talked about this sometimes among patients: Whac-A-Mole. We have effective tools to bop it on its head and then go on with your life.

Editor’s Note: obinutuzumab, or Gazyva, and high doses of steroid

That was because I’d already been diagnosed with another condition, so my CLL doctor had to be very thoughtful about how to treat CLL without negatively affecting the other condition, myelofibrosis. He did it right. It worked out well.

Reacting to the steroid

The steroid was a funny part of it, because when you get steroids, you can get pretty hopped up. They were giving me medicine I could take if I was having trouble sleeping, and I was. But when it wasn’t time for bed, which was most of the time, I was cleaning the house or shopping for groceries.

Esther just sort of sat there while I’m [whooshing around]. If you had a fast-motion camera, you’d see me going all over the house, doing things, going on errands, fixing things, really wired. Then at some point, you crash, and then you do it again. But it worked.

»MORE: Cancer patients share their treatment side effects

How did you manage the roller coaster of emotions?

You’re going to get through it. I think for anybody who’s been through cycles of cancer treatment, you’re in this tunnel, in a way, but there’s light at the end of the tunnel. There’s a date when you believe you’re going to stop.

You’re getting powerful medicines. You understand that they likely have some side effects. You just have to get through it. When I was originally treated, I developed increasingly serious nausea. If I walked into the clinic, just the smell of the clinic made me nauseous, not even having treatment.

There’s a goal, and the goal is that the treatment hopefully will be finite, and your disease will be controlled. That’s happened to me a number of times.

DVT and Myelofibrosis Diagnoses

DVT diagnosis

I never expected to be diagnosed with anything other than a recurrence of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Never expected it. I would go to the gym with my wife, Esther, early in the morning, and I noticed that I was getting leg pain in my right calf. Pulled a muscle, right? Gym, makes sense.

It continued a second day and a third day. We were actually at a shopping mall near where we lived. This was in Bellevue, Washington. We’re going from one side of the mall to the other, and I’m limping, trying to disguise it for Esther. I didn’t want her to really say, “What’s wrong?”

Anyway, it’s in the evening. We get home. She’s putting our youngest child to bed. I’m kind of concerned, and so I called the consulting nurse through our insurance company — the little number on the card if you have that kind of insurance. The nurse said, “I’m going to get the doctor to call you.”

We were in a program. My wife worked for Microsoft and they actually were testing doctors making house calls. The doctor called, and I said, “I’ve got this pain in my leg.”

He said, “Is your calf red?”

I said, “Yeah, it’s little red.”

“Is it warm to the touch?”

“Yes, it is.”

“Do this maneuver with your leg: turn your ankle, do the stretcher. Does that hurt?”

I said, “Yes, it does. It’s a pulled muscle, probably.”

He said, “I don’t know about that.”

I said, “Do you want to come make a house call?”

“No. I want you to go to the emergency room.”

“When?”

“Now.”

I said, “Do I need to call an ambulance?”

“No.”

I said, “My wife and kid are asleep.”

Going to the hospital

I snuck out of the house at like 11:30 at night. I didn’t want to wake them. I drove to the hospital. He had called the emergency room to tell them I was coming. They did an ultrasound. It was the weirdest experience because the ultrasonographer, in those days anyway, she was moving the ultrasound wand around your body, and then she was talking to the machine.

I guess it would make some recording for the radiologist or whatever. I had no idea what she was saying. She did the right calf, and then she did the left leg. I said, “Why are you doing left leg? I don’t have any pain there.”

She said, “That’s the protocol. We have to do that.”

I’d had a cough at the time, by the way.

A little while later, the emergency room doctor came in. He said, “Congratulations, you have a DVT, a deep vein thrombosis, a blockage in your right calf. You also have one higher on your leg on the left side that you don’t feel, but it’s there. And guess what? You’ve got pneumonia, and I’m putting you in the hospital now.”

Anyway, I finally called my wife. Then the family heard about it, and they’re all showing up the next morning. I’m hospitalized for this DVT, which you can die from if it goes to your lungs, called a pulmonary embolism. All right.

Clinical trial #2

As I was finishing treatment over a few days, there was a guy who’s sitting in a chair in my room. “Who are you?”

He said, “I’m a clinical trial coordinator. We have a trial for a blood thinner to prevent DVTs, recurrence of DVTs. Would you like to be in it?”

I thought, “I’d been in a clinical trial for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. It worked. Now I’ve got this other thing. I don’t know what the hell it is. Maybe that’s a good idea.” So I signed up.

I was in the clinical trial for a blood thinner, and they were monitoring me, which they do very carefully when you’re in a clinical trial. They do all kinds of stuff, EKGs and blood tests and regular visits. You’re like a VIP. I love the attention. It’s great.

Then the principal investigator called me and said, “Something’s out of whack with your blood. Not blood thinner stuff. You need to go back to your hematologist here in Seattle.”

So I did, and he drew 10 tubes of blood. Okay, then I forgot about it. I was in the trial center. I went to the major convention for blood cancers, called American Society of Hematology. I tried to go as sort of a reporter every year.

Myelofibrosis diagnosis

I was getting out of the taxi one day there at the convention center, and the phone rang. It was a Seattle doctor. He said, “I got to talk to you.”

I said, “What?”

He said, “You have a blood cancer.”

I said, “Chronic lymphocytic leukemia? I’ve already had that.”

He said no. He said, “Myelofibrosis.”

“What the hell is that?”

He said, “It’s scarring in your bone marrow.”

“How do you know?”

He said, “We did genomic testing. You have the condition, and it’s driven by the gene called JAK2 V617F.” This is like gobbledygook, right? “Therefore, we know it’s myelofibrosis.”

I said, “What do you do about it?”

He said, “Nothing right now. Someday you might need a bone marrow transplant.”

I was scared. The only other thing I’ll say about the diagnosis was I’m now at a convention of 30,000 hematologists. Now, I knew a lot of them from CLL, and they were very upbeat about new treatments for CLL, which have continued. They were very upbeat. “CLL, oh yeah, we got a lot to offer patients.”

I said, “I may have this other condition, myelofibrosis,” and their face would fall. I knew it was fatal, potentially fatal, and that they didn’t have a lot to talk about.

Myelofibrosis treatment

I happen to know the doctor who is world famous, who had interviewed previously about myelofibrosis, although I didn’t know much about it.

He said, “Come see me in Houston.” He was an MD Anderson specialist, a world expert. He said, “We’ve got something to talk about now.” The funny thing was, at the same convention, they have exhibits of different drug companies and stuff like that. There was this little booth for a company that had just gotten approval for the first inhibitor of this JAK V617F gene to tamp it down for people with myelofibrosis.

Guess what? A few months later, that newly approved drug became my treatment, and it was highly effective. Diagnosed with something I never heard of again. Stranger in a strange land. Thank God medical science had something to offer, which worked.

Maintenance Therapy

Can you describe what it’s like to be the person who has benefitted from clinical trials twice?

When you talk about cancer, I wish we could say there’s been miraculous progress in every cancer. That’s not true, but there’s been a lot of progress, and it continues. I think I’m just a really lucky guy that the illnesses, the cancers that I’ve been diagnosed with, have been treatable in ever more refined ways as I’ve lived with them. Thank you, God, that I’m living at a time where there’s been progress for what I have.

I think my advice to patients and family members is turn over rocks. Not with false hope, not somebody selling you snake oil, but with validated, real evidence-based information. Is there somebody or something for you that could make a difference and is an example of medical progress for what you have?

Now, I’ll step back for one second. In cancer, there are a lot of people who don’t have the appropriate testing or the most knowledgeable pathologist look at their blood or their tumor type. They get a misdiagnosis, or there’s not a clear test that’s done to show their version of a cancer.

Job 1 is to know what you’re dealing with. Job 2 is to have a health care team that’s knowledgeable in the full range of options.

I think Job 3 is to have hope that with the right team, with the right diagnosis, that either now or coming soon, there may be something that can help you. If that helps you but peters out, there may be something waiting in the wings to help you even better. That’s what’s happened with me.

Switching in 2020 to another recently approved treatment

The original medicine I was on to inhibit the myelofibrosis, the trade name is Jakafi or Jakavi outside the U.S. The generic name is ruxolitinib. You learn these long words.

Then when I came to San Diego on that drug, eventually my specialist — who’s also a scientist and had done a lot of the groundbreaking work in another drug in that class, fedratinib or trade name Inrebic — said, “I think this may offer you some advantage. Let’s consider changing to that.”

I did, and it’s worked well. I trust in my doctor. Both medicines have worked well, and I’m leading a pretty good life.

Pills and hemoglobin shots

That Jakafi I took, I don’t remember what color the pills were. Sometimes the dosage moves around over the years. I take 4 of these red Inrebic pills every night, and then your blood counts are monitored. My hemoglobin was going down, and going down lower than I’d ever had before.

My doctor, Dr. Jamison, has had good results using a drug called Reblozyl (the trade name). Luspatercept is the generic name. It’s not approved for myelofibrosis, but she’s getting Medicare to pay for it through some scientific argument that I don’t understand.

You get a shot pretty quick, either in your belly, your abdomen or your arm. The nurse gives it to you at the clinic. That boosted my hemoglobin from a low of 8.8 to 11.5. What did that mean? It made the difference for me. Huffing and puffing going up a flight of stairs to being able to ride my bike and not feeling like I needed to lie down. I’m very, very grateful for that.

I’ve done that about 3 or 4 months now, and I’m very grateful that that exists.

How have you managed everything?

I think you have to be a proactive patient. It may be your spouse or your adult child or your best friend. I think you have to look for answers. Not false answers, not phony answers, but you have to look for real answers and providers who are knowledgeable.

I’m very grateful that I’ve been able to do it. But I had to look. I had to push for that. I had to be a consumer. So many people are smart shoppers about buying a house, buying a car, buying a new sweater. Why should it be any different if you’re facing a life-threatening cancer? You’re not a little lamb. You and your family are consumers, so be savvy.

I would say be positive. We’re going to find the right answer. We’re going to find who’s in the know. We’re going to find and get a full understanding of our options. Both what’s approved, what’s maybe experimental, what could make sense. We’re going to find out where there’s financial assistance.

In the meantime, we’ve been given time. If you’re having some good treatment, what does it give you back? It gives you time. Then you can’t say, “I’m going to ‘woe is me’ and mope.” You have to say, “I’ve been given today. What am I going to do with it? What am I going to do that’s positive today?” That’s how I approach every day.

Inspired by Andrew's story?

Share your story, too!

More CLL Stories

Lynn S., Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL)

Symptom: Elevated white blood cell count

Treatments: Chemotherapy, targeted therapy (BTK inhibitor)

Serena V., Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL)

Symptoms: Night sweats, extreme fatigue, severe leg cramps, ovarian cramps, appearance of knots on body, hormonal acne

Treatment: Surgery (lymphadenectomy)

Margie H., Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia

Symptoms: Large lymph node in her neck, fatigue as the disease progressed

Treatment: Targeted therapy

Nicole B., Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia

Symptoms: Extreme fatigue, night sweats, lumps on neck, rash, shortness of breath

Treatments: BCL-2 inhibitor, monoclonal antibody

4 replies on “Andrew Schorr: Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL) & Myelofibrosis Stories”

Hi Ashok, I’m also from Bangalore. Which doctor do you go to? I’m the phase of best and trustworthy doctor now for Myelofibrosis

My prayers for your dad. Let’s hope for miracle !

I just listened to your videos with Ellen Ritchie about ET. And found them very informative . I was diagnosed with ET last October and am slowly but surely coming to terms with my diagnosis and researching more about it. I live in Del Mar and am a patient at UCSD.

Thanks for all you are doing to support MPN patients – please reach out to me if there is anything going on in our “shared neighborhoods “ that might be of interest or helpful to me .

Keep up the good work – we are lucky to have people like you in our corner !! And I hiked Torrey Pines yesterday inspired by the video to “get off the couch”!!

Thank you for all the patient stories. It really gives me hope that someday there will be a more affordable cure to MF. My dad has been with this disease for close to 30 years and recently stopped responding to Jakafi medication. He is now on palliative care and doctors are of the opinion that there is nothing much that can be done from now on. I trust my doctor completely, however just wanted to discuss or talk to someone who is currently in the advanced stage of the disease like my dad and how are they managing. My dad is currently on Thalidomide and Danogen primarliy. I am from Bangalore, India if this helps.

Appreciate if we can get any help.

Still on the look out for best best doctor