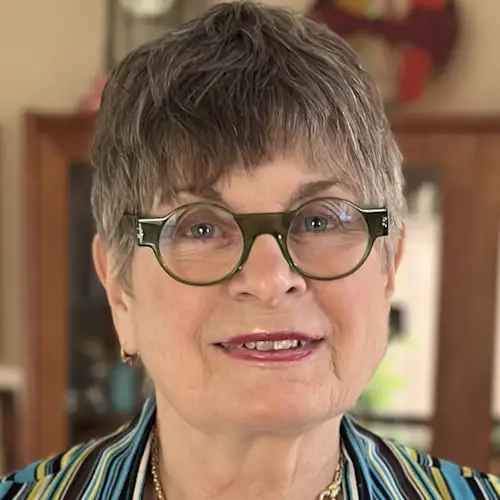

Ruth Fein: Myeloproliferative Neoplasm (MPN) Story

Ruth shares her Myeloproliferative Neoplasms (MPNs) story, a rare blood cancer, and builds awareness to help bridge the gap in a world where so little information exists.

In her story, she shares her experience in navigating her rare disorder, self-advocacy, how her life and outlook evolved with her diagnosis, why she chose to join a clinical trial and her hope in the ever-growing research toward rare cancers such as hers.

- Name: Ruth R.

- Primary Diagnosis:

- Myeloproliferative Neoplasms (MPNs)

- Essential Thrombocythemia (ET)

- Polycythemia Vera (PV)

- Secondary Diagnosis

- Symptoms:

- Anemia

- Bleeding

- Treatments:

- Daily chemotherapy

- Clinical trial

This interview has been edited for clarity. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider for treatment decisions.

Myeloproliferative Neoplasms (MPN) Cancer Diagnosis & Evolution

What was your initial diagnosis?

I was 38 years old when I was diagnosed first. That was with something called Essential Thrombocythemia (ET). And about 15 years later, that transformed to PV, which is Polycythemia Vera.

But when I was first diagnosed, and this was a number of years ago, it was called a blood disorder. Then a number of years went by and the World Health Organization reclassified it as a blood cancer.

Today, it’s called a group of rare blood cancers and Essential Thrombocythemia is basically an overproduction of platelets and Polycythemia Vera is like this little switch that goes off and says, “Oh no, you’re bone marrow. Listen to me, you don’t need extra platelets. You need more red cells.” So your platelets go down, but your red cells go high.

The third disease in that category is something that I’ve also progressed to over the years called myelofibrosis.

“What happens in myelofibrosis, which is very rare – only about 10% of people with either ET or PV progressed to myelofibrosis. I’m just one of the lucky ones.”

What happens in myelofibrosis is your bone marrow starts to produce fibrosis, which is scar tissue or scarring of your bone marrow. And what that does is it prevents your blood cells, or your stem cells, from producing healthy blood cells, red cells, white cells, and platelets.

You become anemic, among other things, and so your high risk for clots and also for bleeding sort of live between this vicarious place between a risk of bleeding and a risk of clotting. That’s a very strange place to sit because the treatments, of course, are exactly the opposite.

»MORE: What Is Myeloproliferative Neoplasm?

How did you process your chronic cancer diagnosis?

It’s a great question because I really think it’s important to make the distinction between chronic and acute cancer. You hear the diagnosis, you hear that “big C” word and I think a lot of times people don’t hear anything beyond that.

“So they then walk out of the office saying, ‘I have a rare blood cancer.’ And that’s how they feel it and that’s how they communicate it and that’s how they research it. They jump to the Internet where they get old, outdated information.”

With any rare disease, particularly with myeloproliferative neoplasms, the research has just accelerated at such a rate in the last five to ten years. Even in the last three years, if you go on the Internet, you’re going to get very different information if you just do a generic search, then if you go to a trusted source like Patient Power and lots of others.

Living with Myeloproliferative Neoplasms

Describe life after your cancer diagnosis

When I was first told that I had Essential Thrombocythemia, I basically lived my life. Five years later I ran the Dublin Marathon. I was on an aspirin a day. I was raising two children. I honestly didn’t think about it often.

But what it did do, and I think that this is something I can share, even though it wasn’t supposed to affect the longevity or quality of my life, they thought at the time, it still made me face my mortality in a way that a 38-year-old doesn’t usually have, what I call, “privilege” to do that. Right? We go on with our lives and we raise our children if we have children, and we work furiously.

I think most people, unless they have a scare, a health scare, don’t face that mortality in the way that gives us the benefit of saying, “Hey, you know what? Let’s slow down and [ask] what’s really important to us.”

As I used to say…”I could get hit by a truck tomorrow.” That was my way of saying “I could also die tomorrow.” But it’s more comfortable to say I might get hit by a truck. It definitely has an effect and it can be a positive effect.

Then when the disease changed to Polycythemia Vera, there were totally different treatments. It comes with much higher risks. I had life-threatening blood clots [and was] hospitalized a couple of times. You know, it did change things and by then they were calling it blood cancer.

Did you tell people that you had cancer?

At that point, I still really didn’t tell very many people in my life, which is a conversation that I often also think is important to have. We can have that.

Everyone deals with a cancer diagnosis and even living with cancer, very differently. And for me, I wasn’t in chemotherapy every day. I wasn’t in a situation that people could see my hair falling out and some of the other things that people live with who are being treated aggressively. I was on daily chemotherapy – an oral drug that was probably the oldest chemo drug available to men or women. But it wasn’t visible.

For me, I didn’t want to be a person who everybody looked at as someone living with cancer and “Oh, how are you and how are you doing?” And all the things that go along with that, and people bringing meals to my doorstep.

However, I don’t want to minimize the importance of all of that. People need different things. I’m just suggesting that we think that people want or people should – there’s a “should” word – tell people, express themselves, share how they feel, and tell their community so their community can reach out to them.

“I’m bringing it up because I think it’s important to acknowledge that everyone doesn’t react the same. Everyone doesn’t have the same needs, and they can change, which is what happened to me.”

Describe your secondary cancer diagnosis

What happened is I had a bout with early colon cancer, which we now think is probably secondary cancer, which is common to have with Myeloproliferative Neoplasms.

I have eaten healthier than anybody I know for my entire life. So when I got colon cancer, my children actually laughed out loud. Not in a cruel way, but saying “How could you have colon cancer?” But it probably was secondary.

The point is they took eight inches of my colon out. I didn’t need additional therapies because it was very early. I was walking around the hospital on day three like Superwoman. I’m feeling great and “You’re doing great. We’re sending you home.” And I went home.

Twenty-four hours later, I had a massive bleed that put me in the ICU for five days, and really recovery for multiple months where I couldn’t really get out of the recliner.

How did colon cancer change your outlook on living with blood cancer?

At that point, I decided to take my disorder, then a blood cancer, to a different level. My acknowledgment of it, my treatment of it. I sought a super-specialist. I was already seeing a hematologist oncologist in the community and I saw a specialist – which, when I was first diagnosed, there was no such thing.

That changed everything, you know? So from there, I realized the high risk that I was at. They did a bone marrow biopsy and found I had myelofibrosis, which is dreaded of the three MPNs because it’s the most life-threatening. And it was offered to me to be on a clinical trial.

Clinical Trial

Why did you choose a clinical trial?

It’s a great question. I think in our society, and maybe around the world, we’ve come to look at clinical trials as a last resort. And for me, that’s so wrong. And I know in your experience that’s so wrong as well, particularly with a rare disease.

“The research is happening so quickly. We have very, very few treatments that are approved. The only way we’re going to get better drugs and better treatments is through clinical trials.”

And so I hadn’t ever thought about it before, quite honestly, but I have a great physician specialist in New York. And she said to me, “You know, there’s a new trial and you would be a perfect candidate. What do you think?” And I, of course, said, “What do you think?”

Because another very important thing with a rare disease, or any disease, is to have a practitioner that you really trust. And that might take a second opinion and a third opinion, but find that person who knows your disease and knows it in and out, and that you trust their judgment. So when she thought I was a perfect candidate. I said, “Okay, I’ll go for it.”

Weighing the risks and benefits of clinical trials

When you go into a clinical trial, you look at the risks, you look at the benefits and you weigh them and you always have the ability to do one of two things. If you’re not doing well, you have the ability to get out. This was, for instance, a two-year trial. You’re not committing to two years.

And the first six weeks were really rough. Really, really rough. And I think a lot of people do walk away. For me, I was encouraged by my practitioner that she was watching me carefully every week and that I was probably going to get past this very early stage of side effects.

So the other option with a clinical trial is if you do well, which I’m doing extraordinarily well after three years, you could stay on that trial. So I’m still on that trial, even though it was a two-year trial. I still meet all the protocols and get my magic drugs, and I’m doing better than anybody expected me to be.

What was the transition from your local oncologist to a clinical trial like?

It was me who was uncomfortable because I felt as if I was second-guessing his expertise, but he did not feel that way. With a rare disease, he had a handful in a lifetime. His entire life of practicing, he had a handful of patients like me, and he didn’t have access to the information at his fingertips or experience as you would find in an academic center.

Being A Patient Advocate

Bridging the gap between community practitioners and specialists

Now, that said, I think one of the things that we can do as people living with rare blood cancer – or whatever conditions we have – and also as a patient advocate, I think one of the things we can do is to help educate our community practitioners.

I think we need to do a much better job as an organization, as individuals and organizations, advocacy organizations, research organizations, and even the media, to bridge that gap between the community practitioners and the specialists. because I was on a drug that [my doctor] was very happy keeping me on that was just controlling my symptoms. But in the process, I got sicker.

And we now know that in particular for myelofibrosis, it’s not just about symptom management. You need to look at more than just your blood counts, which is the typical thing that someone outside of an academic institution is going to do – they’re going to look at your blood counts.

I would go to see [my doctor] and he would say, “Wow, you look great. Your blood counts are great. See me in another three months.” And of course, that’s not the answer, because all that time my bone marrow was producing fibrosis.

I was lucky that you know, while I had episodes, I was lucky that I saw someone when I did.

Describe your experience with bone marrow biopsy

Bone marrow biopsy is a very common procedure for blood cancer patients. It is, in my opinion, and in a lot of experts’ opinions, overused. And particularly in clinical trials, it has become an endpoint, or at least a measurement, if not an endpoint, of how a person is doing and they build it into protocols for clinical trials.

The [clinical trial] I’m on, I had to have a bone marrow biopsy every six months. When in fact, after the first one, at six months I was doing better. [After] the second one, I was doing great. I probably didn’t need to have them every six months continuously unless something changed.

So most super specialists that you speak to will want to do a bone marrow biopsy at the beginning of diagnosis and [again] if there are any changes or they’re concerned about something that may be different.

And the experience of a bone marrow biopsy makes me want others to advocate for themselves because it’s not fun. I know I’ve spoken to many people who say it’s not at all for them – their experience was not terrible. For me, it was.

I had two terrible bone marrow biopsies where the anesthesia didn’t work and they’re basically drilling into your bone. Just visualize that.

Discovering a better option for bone marrow biopsy

What I did is I had one after I had two bad [biopsies], it was suggested to me by someone that they could do this with – you know, under no anesthesia, but like sedation– with interventional radiology. Someone mentioned to me that they always have their bone marrow biopsies with interventional radiology, and that was total news to me.

So I asked for it and they did the first one and the next one that way. And I said quite clearly, “I am never ever having one without again.”

I think [bone marrow biopsies are] barbaric. And I think any practitioner who does them needs to have one themselves before they do it on their patients. And I don’t say that to scare people. Many people have them and they’re fine.

“I know [interventional radiology is] expensive, but we spend our health care costs on lots of things. Why shouldn’t it be on something that’s so directly related to comfort and pain?”

We do it for other procedures. Just because there isn’t a large patient population that needs a bone marrow biopsy, it should not keep us from doing it in the best way we know how.

Reflections

Well, I’m a health and science writer, so one of the things I did is I used that tool to start to write about MPNs, and that’s because others weren’t. It’s a rare disease, and what I started to hear through a very small grapevine, is that people didn’t have materials to share with their friends and families to explain what they had.

How did you share your cancer story with others?

Again, it comes back to “I have blood cancer” and that’s so frightening. Likewise, practitioners didn’t feel as though they had great consumer-level materials to share with patients to explain it. So it happened by accident.

I actually wrote a story. I’ve written on and off for the New York Times for a number of years, but I wrote a first-person story that they accepted and published. That was in 2021, and it’s the first time I really told my story publicly.

The outpouring of support, even still, is amazing to me. Not to pat myself on the back at all, but to make me recognize how large the need was and still is for people to talk about and write about and read about rare cancers.

And so I started using my tools to do that and I started writing more about it. I started doing webinars for Patient Power, which I’ve really enjoyed. I started working with the Research Foundation and writing for their newsletters and various other publications.

“Little by little, I’ve become involved as a patient advocate along the way, and that’s been really good for me and that’s not how I initially saw it. I saw it as my way to help others.”

How did your lifestyle change?

I’m probably a little outside the norm in many things, but in this as well.

I’ve eaten healthy my whole life – probably as close to the Mediterranean diet as is now prescribed for anti-inflammatory issues such as [Myeloproliferative Neoplasms} and so many other cancers. So it wasn’t about diet, it wasn’t about exercise – I’ve been active my whole life. Some of that had been taken away from me.

I went from, for a while, not being able to walk up the street without holding on to a lamppost at the end of one block to having to sit in a recliner and not do much some days because the fatigue just made it impossible.

I then had to become active again, and that’s a long haul. People who have gone through that, for all kinds of reasons, know that that’s a slow process. So for me, it was relearning rather than learning.

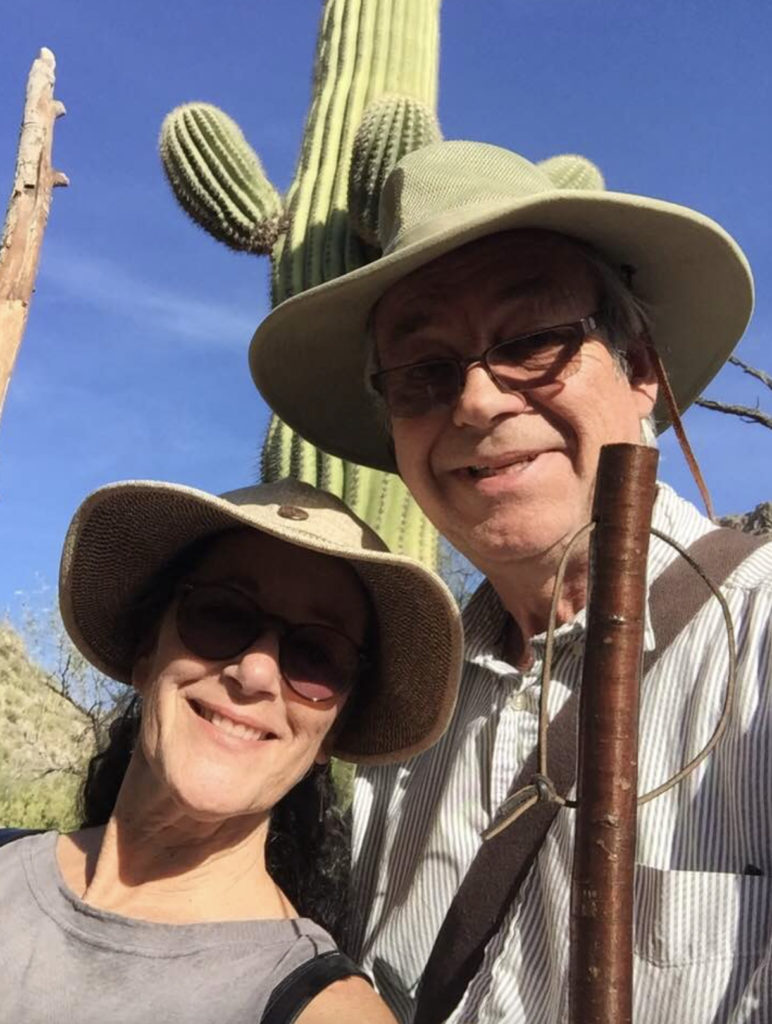

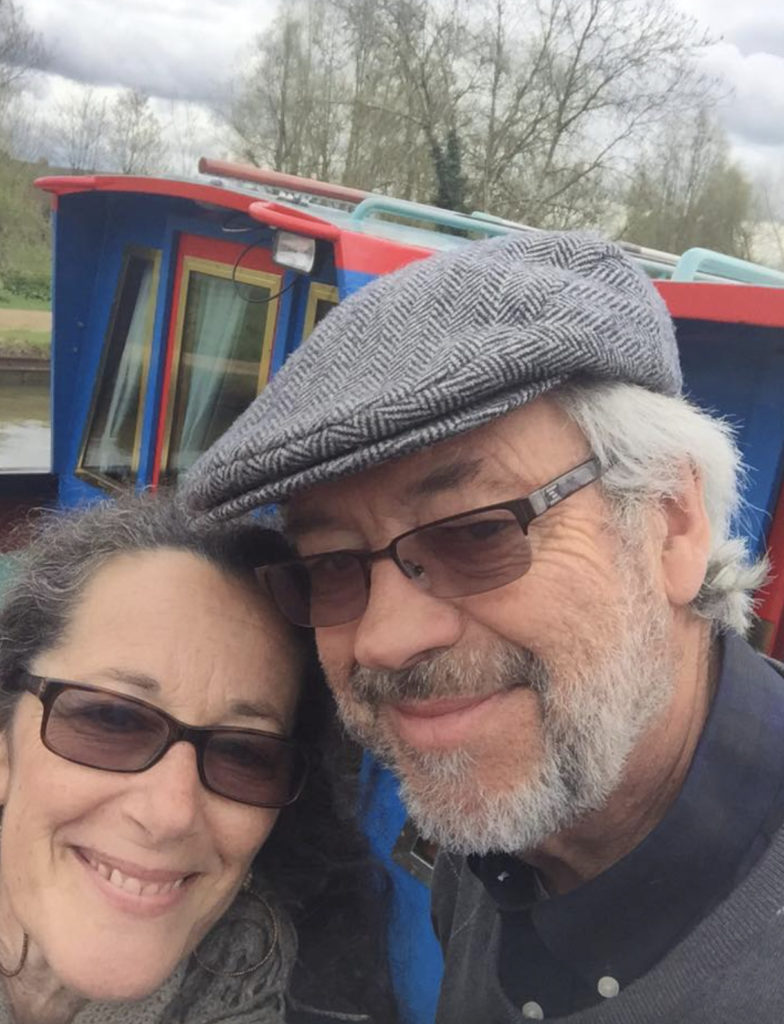

Probably more than all of those things, in terms of lifestyle, was me learning to share my own feelings and experiences. And my dear, sweet husband would tell you I had to learn how to ask for help, which I’m not good at. And his main frustration, which you as a care partner know, is that he wants to help and I don’t always allow him to because I want to do things myself. Those things are where the changes came in for me personally.

What advice do you have for someone diagnosed with Myeloproliferative Neoplasms (MPNs)?

I think number one on my list is, to find a specialist. And it’s a shame that has to be at a major academic center. Because for so many people it has nothing to do with geography as much as it does socioeconomic status and every other thing that defines us or surrounds us. But there are ways.

If anything positive came out of the pandemic for us – a patient population – is that most of the super specialists I know, that I speak to in my work, are very happy to have a remote consult.

It doesn’t mean you need to give up your local hematology oncologist or whoever you see in your community. It means that you need a bridge to a specialist who can work with that physician and make sure that they’re seeing, not just the whole you and the whole picture, but also the latest and greatest of what’s happening there in the academic centers that they can do in their clinic.

Clinical trials, again, are a misnomer. Clinical trials don’t have to be done in an academic setting. They can be done by community physicians. They just don’t always take that opportunity or know about those opportunities. So finding a specialist, no matter where you live. You can do it remotely. Do the research, and get your answers.

Number two. I think you have to believe – and this is about learning and educating yourself so that you can educate others. You have to believe in the difference. As I said before, it’s sort of like fact-based hope, as I like to call it. The facts are different now than they were even three years ago.

This is a chronic condition. This is not an acute condition where you can cut it out, radiate it out, be in remission, and go through life. This is something you’re likely to live with, and because of that, you need to be educated and your hope comes from the education.

What hope do you want to share with those with Myeloproliferative Neoplasms (MPNs)?

Your hope will come from how fast things are changing and how many new answers there are out there. New medications. New treatments. The more you learn, I think you will start to believe that there really is a difference between chronic and acute cancer. And that many cancers today, because of our advancements in science, many cancers that were known as killers just a few decades ago are now chronic because people can be treated and live a good, long life.

What is your top tip for those with cancer?

The last thing on my list is advocacy, and I touched on that before.

Be your best patient advocate. Advocating for yourself is your best patient advocate. The on bone marrow biopsy is a perfect example. You have to say that that’s what you want. “I want my bone marrow biopsy with interventional radiology.”

The other thing is, I have very tiny veins and they roll. Just getting blood work done, which I have to do every three weeks, is an emotional chore because sometimes it takes six or eight sticks. It’s not the pain of it, it’s the stress of it. So an IV is always really stressful for me. When I go into any procedure, I say right from the get-go, “I want an IV Specialist because I don’t want you to feel the stress of having to stick me eight times. It’s going to hurt you more than me.” Which it does, you know?

“You need to learn the things to advocate for. It’s not about being a bothersome nuisance. It’s about getting what you need, using the resources that are at hand to everyone’s benefit, and using the great science that we’ve advanced to, to make life easier, less stressful, and healthier.”

More Myeloproliferative Neoplasms (MPN Stories)

How to Support Someone with Cancer: Karina & Jesse's Myelofibrosis Story

“I underwent a lot of sadness, hardship, and difficulty, and all that entails. But I pressed forward in hope for sure. There was a lot of hope that just kept me going all those years.”

Demetria J., Essential Thrombocythemia (ET) progressing to Myelofibrosis

Symptoms: Extreme fatigue, stomach pain (later identified as due to an enlarged spleen), dizziness, shortness of breath

Treatments: Spleen-shrinking medication, regular blood transfusions, bone marrow transplant

Neal H., Prefibrotic Myelofibrosis

Symptoms: Night sweats, severe itching, abdominal pain, bone pain

Treatment: Tumor necrosis factor blocker, chemotherapy, targeted therapy, testosterone replacement therapy

Andrea S., essential thrombocythemia (ET) progressing to Myelofibrosis

Symptoms: Fatigue, anemia

Treatments: Targeted therapy (JAK inhibitor), blood transfusions, allogeneic stem cell transplant

2 replies on “Ruth Fein: Myeloproliferative Neoplasm (MPN) Story”

I would like to know what clinical drug Ruth F participated in and the drug she is on. My husband has the disease and may be a candidate for clinical trials. Anything else you are willing to share about your journey would be greatly appreciated. Thank you.

Thank you for sharing. I was first diagnosed with PV in Alabama (Anderson CC) in 2018, then a few months ago (2023) with MDS/MPN by a specialist who miraculously joined the hospital here in Guam. He just left for Abbott Hospital in MN 🙁 After almost 4 years of regular phlebotomies and baby aspirin, Dr. Stanley Kim diagnose my illness and prescribed Hydroxyurea…my blood levels have returned to “normal” and I feel much better. Since my first diagnosis of PV till today, I still feel very alone in this health experience. I’m an avid scuba diver, and stay active, determined to enjoy life. While diving, I often hover around rare underwater fauna or creatures in wonder and curiousity. That’s what it feels like, having MDS/MPN, as I hover around all the information (and myself). I feel alone in this ocean. But I know there are others out there similar to me.