Stephen Huff’s Stage 4 ALK+ Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Story

Stephen Huff was diagnosed with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) before he was even 30. In his in-depth story, Stephen, who helps with lung cancer patient advocacy, shares his treatment of targeted therapy and radiation therapy, the stigma of lung cancer and smoking, and family planning after a cancer diagnosis.

- Name: Stephen H.

- Diagnosis (DX)

- Lung cancer

- Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC)

- ALK+ mutation

- DX Age: 29

- 1st Symptoms

- Shortness of breath

- Pain while talking (jabbing sensation)

- Wheezing at night

- Treatment

- Targeted therapy

- Oral TKI drug: alectinib (brand name Alecensa)

- 4 pills taken twice a day

- Ongoing

- Radiation therapy

- SBRT: stereotactic radiation therapy, also called stereotactic external-beam radiation therapy

- 5 sessions altogether

- Targeted therapy

Attitude directs you in life and how you view things. It gives you perspective.

It gives you the opportunity to look beyond your circumstances and to help others.

Stephen H.

- Video: Stephen on Getting Diagnosed

- First Symptoms, Tests, and Scans

- What were your first symptoms?

- When did you finally go to the doctor?

- What happened at the first medical visit?

- You scheduled an appointment with a specialist

- Self-advocating for more testing to get answers

- What happened with the ultrasound and CT scan?

- How did you get the CT scan results?

- When did the possibility of cancer really sink in?

- How did you process the initial bad results?

- Describe the ultrasound-guided core needle biopsy

- The biopsy is not the usual procedure for lung cancer patients

- Describe the imaging tests you had to undergo to be staged

- Describe the PET scan

- Lung Cancer Diagnosis

- How did you finally get the diagnosis?

- Describe the moment you heard it was cancer

- You had to wait for the gene sequencing results for the full diagnosis

- How did you pass the time while waiting for results?

- Your genetic mutation: ALK+

- How did you process the cancer diagnosis?

- How did you break the news to loved ones?

- Any tips for others on how to share a cancer diagnosis?

- Video: Stephen's Treatment

- Treatment (Targeted Therapy)

- Did you consider a second opinion?

- 2 oncologists with different treatment recommendations

- Targeted therapy drug: TKI (tyrosine kinase inhibitor)

- How did your oncologist describe the targeted therapy drug regimen?

- What are the alectinib side effects?

- You started feeling great soon after starting treatment

- You were able to go back to work

- Managing the cancer like a chronic disease

- Paying for the alectinib

- Advancements in lung cancer treatment

- Radiation Therapy

- Video: Stephen's Reflections

- Reflections (Quality of Life)

- Being your own advocate as a patient

- Dealing with the stigma of lung cancer

- How was it being an adolescent young adult (AYA) cancer patient?

- How did you plan for the future (family) while dealing with a late-stage cancer diagnosis?

- Describe how you approached fertility preservation

- What does survivorship mean to you?

- Last message to patients

This interview has been edited for clarity. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider for treatment decisions.

Video: Stephen on Getting Diagnosed

Introduction to Stephen

I grew up in Tennessee. In the Southeast, sports is more than just sports. It’s a way of life. I grew up playing sports my entire life, specifically baseball.

I was fortunate enough to play at the college level and even more fortunate to get drafted by the Chicago White Sox. Sports has been a big part of my life.

There are so many lessons that you learn. You learn about things like work ethic, persistence, all these various things that are tools you put in your tool belt moving forward as an adult.

I love talking about my journey, specifically as it relates to my athletics background.

I grew up in Tennessee. I live in Franklin now. In my college and professional years, I lived almost everywhere. I think I lived in a total of about 15 different states at one point or another. That was just through sports and traveling!

I am here now. My roots are here. My wife and I have started our family. Everybody always asks if we wear cowboy hats and cowboy boots to work, and we don’t. We don’t ride horses.

We are the music city. I won’t say we’re the country music city. We’re known for country music, that’s for sure, but it’s a great place to live. I look forward to spending the rest of my life with my family locally here in the Nashville area.

First Symptoms, Tests, and Scans

What were your first symptoms?

I was in a transitional state of my life. After my college baseball playing career was over and I got drafted, I really transitioned myself into a different level of sports, working out, fitness — whatever you want to call it.

When my playing career ended around 2013 to 2014, I joined the rest of the real world in a normal job. I just assumed it was normal to gain weight, get out of breath, and just not be able to do some of the things I was used to being able to do.

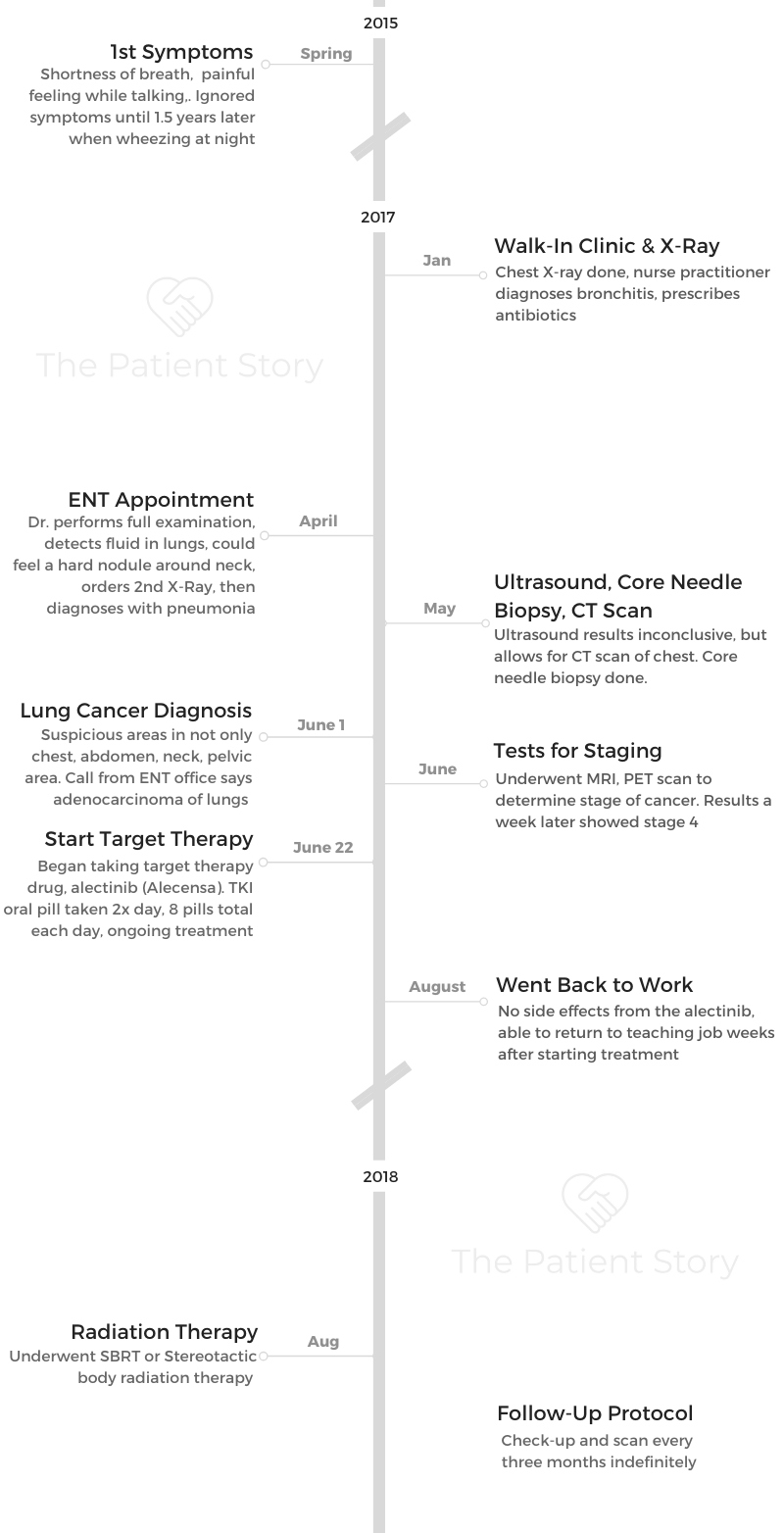

I started to notice my very first symptoms in 2015. The reason I can remember is because I was in graduate school and student teaching in Georgia, where I was also coaching baseball.

I began to have shortness of breath. I think because of the timing of the year and all of the things I mentioned before, I just assumed it was allergies or something normal, that this is what happened to normal people.

When I think about it in hindsight, I obviously can self-reflect and say that was the first sign that something was off with my body.

When did you finally go to the doctor?

I lived with this shortness of breath for some time. I would even get to the point where I could code it, I could keep it discreet, and I could talk around it.

The best way to describe it is I would be talking, and it would feel like someone was jabbing me in the stomach. It would cause me to cringe my stomach up, and I just learned to deal with the symptoms.

Our bodies are so unique and fascinating in that way. Our brains, once we acknowledge something, we can forget about it and continue on. We do this with more than one thing like shortness of breath. We do it with other ailments.

I carried this on for at least a year, possibly two years, until I started to get really, really wheezy. That’s the best way I can describe it. When I would lie down in bed at night, it sounded like there was fluid in my chest.

I remember lying in bed looking at the ceiling, not able to sleep, and my wife said, “Stephen, I really think you should go to the doctor. It’s not normal. It’s beyond keeping you awake at night. Now it’s keeping me awake at night, so I think you should go see a physician.”

What happened at the first medical visit?

Thinking nothing of it, I didn’t even think to make an appointment with my primary care physician. At the time, I had a scheduled appointment, but it was at least around 10 or 11 months away.

I didn’t even think to call and to try and push it forward. What I did was I went to a walk-in clinic. I complained about breathing, and I complained about the wheezing at night.

They prompted me to get a chest X-ray, which yielded a diagnosis of bronchitis. The nurse practitioner said I had bronchitis, gave me some antibiotics, and said I should be fine.

I distinctly remember walking out of the parking lot, thinking in my head that I’d never had bronchitis, but I was pretty sure it wasn’t bronchitis. It might be, but something inside of me was telling me that it was more than that.

You scheduled an appointment with a specialist

About 2 or 3 weeks later, I scheduled an appointment with a specialist. I wanted to go see an ENT, or ear, nose, and throat physician. For some reason, I had always thought this was allergy related and thought that was the right physician to see.

When I saw the ENT, he gave me a full examination. He also, along with the fluid in the lungs, could feel a hard nodule above my right collarbone. You know how they do the inspection; they check your neck. That was the second alarm bell.

With insurance, nothing is easy, and nothing is straightforward. I had to do a second X-ray before I could do any further testing. That’s when the ENT doctor sent me to do an X-ray, which yielded nothing except possible pneumonia.

I’m sitting here with a bronchitis and pneumonia diagnosis. I still have no answers, and I’m not getting better.

Self-advocating for more testing to get answers

I called the physician to ask if there was further testing that could be done, specifically with the nodule in my neck. When we have these nodules, bumps, and what have you, we check the internet and try to find as much information as possible, which leads to all of this fear and anxiety.

After reading the internet for several hours on end, I decided that I needed to get that nodule checked. We had an ultrasound. That was the third diagnostic test done.

What happened with the ultrasound and CT scan?

The ultrasound result was inconclusive. I don’t remember specifically getting any kind of negative feedback, but I do remember getting an inconclusive follow-up. It was at that point that we had checked all of the boxes to finally get the chest CT scan approved.

The chest CT scan is what ultimately threw up the alarm bells, the whistles, the lights. It was the imaging that actually set off the fire alarm for the lung cancer.

How did you get the CT scan results?

I remember that I had gone to Cracker Barrel, which in the South is a very popular restaurant. I was celebrating my first summer as an educator and soaking it in.

On my way home from the restaurant, my phone rang. It was the doctor telling me that my CT scan was not good. They didn’t know what was going on in my chest and my body, but they said it appeared to look like cancer.

When did the possibility of cancer really sink in?

He said I needed to go into his office as soon as possible and drop everything I was doing. I remember distinctly filling out the paperwork, and the last question on there was if I had a living will. That was the defining moment. That’s when it all sank in that this was real.

That this was not only real, but something life-threatening.

As a cancer patient and survivor, I think the worst part is the waiting because it’s the unknown. That’s when your mind starts to race, and you start imagining things. You have all these ideations of things.

The CT results yielded a lot of things. Basically, there were several suspicious areas in not only my chest, but also in my abdomen, my neck, and my pelvis area as well.

That was probably the realest, scariest moment of the entire journey because up until this point, I was in my own brain. This was all arbitrary and miniscule. I was healthy, young, fit, and this was not something that I had taken seriously up until that point.

I’ll never forget, as a new teacher, I had just finished my first year as a teacher. I’m on cloud 9. I’m starting my first summer as an educator, which is the best part of teaching.

I had all of this happen the day after the last day of school. For me, this was a black cloud. It was very traumatic.

How did you process the initial bad results?

With lung cancer, we ordered a Foundation test, a biomarker genomic sequencing test. It takes 7 to 10 days. That period was a nightmare. I was not sleeping.

When someone tells you you’re sick, sometimes you feel more sick. It was very mental for me in that regard because up until that point, I had been so healthy.

I’d been going to the gym. I was exercising, not as rigorously as I used to, but then I couldn’t. I started to feel sick and feel worse. The combination of those 2 things was really, really hard for me to deal with.

Describe the ultrasound-guided core needle biopsy

When they found this nodule in my neck, they sent me to an interventional radiologist. They took an ultrasound remote and did an ultrasound-guided core needle biopsy.

Essentially, they find the nodule and try to get as much tissue sample as possible. When they send that off, the first result that comes back is whether or not it’s cancer, and if so, what kind of cancer.

If it is cancer, they take the remaining core tissues and start the gene sequencing to see the mutation arrangements and the biomarker testing. All of those things can dictate your treatment options.

The biopsy is not the usual procedure for lung cancer patients

For lung cancer patients specifically, I am a rare case in the sense that I had a lymph node sitting right there on the surface level of my skin that they could access with a needle. Most patients do not have that luxury. Most patients never have that.

The standard procedure is usually called a bronchoscopy, or what they may call a VAT (video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery). They sedate you in an outpatient procedure, go into your lungs, and scrape from the inside of your lungs. You’re asleep the entire time.

I’ve heard that procedure can be good or can have some side effects. I was a rare case in that I had a nodule sitting right next to my neck that they could easily access, leading to a core needle biopsy.

Describe the imaging tests you had to undergo to be staged

A lot happened on June 1st. I received my diagnosis, and I also had to be staged. To do this, they wanted to do not only a PET scan, but they wanted to do a full MRI for the head, neck, thoracic, lumbar, and sacrum.

If you’ve ever had an MRI, you know it is not the world’s greatest experience! I did one with and without contrast. Each section was 15 minutes, twice, so I spent a good 2.5 hours in an MRI tube just to get staged, along with the PET scan.

Describe the PET scan

The PET scan is a little different. They give you the glucose and the liquid form of radiation to spot the cancer. That was a little less invasive than the MRI.

Lung Cancer Diagnosis

How did you finally get the diagnosis?

I was passed off to the oncologist based on something in the ultrasound result. It was still speculation at that point. I didn’t even really know what an oncologist was. I was like, “Is that a specialist?”

I think that was the safe move at the time. When I got the results from the CT scan, it just further validated that I had a lot going on in my body.

After we got the results from that CT scan, the oncologist then ordered the core needle biopsy to confirm what that node in my neck was. We did that at the end of May. I found out on June 1st, 2017, that I had adenocarcinoma of the lung, stage 4 lung cancer. It was non-small cell lung cancer, which is the most common type of lung cancer.

Describe the moment you heard it was cancer

When I went in on June 1st, it was pretty much all set in stone. I had made up in my mind that it was cancer. It was the worst-case scenario.

The physician presented the treatment options. We talked about treatment, but I don’t remember a whole lot after hearing, ‘Unfortunately, it is cancer.’

It’s such a surreal experience. It’s so hard to remember everything because it’s something you’re not equipped to deal with.

»MORE: Read different experiences of a cancer diagnosis and treatment

You had to wait for the gene sequencing results for the full diagnosis

We still had to wait for the remaining results of the core needle biopsy to see if I had a targetable mutation-driver of my tumors before I could jump straight into treatment.

How did you pass the time while waiting for results?

My advice would be to just find something to occupy your brain. For me, idle hands are the worst. When I sit at home and don’t do anything, I go crazy.

I have to find something to do, even if that means I really don’t want to do it or I’m in the worst possible mood. Just getting up and going for a walk or a hike with my wife, getting my mind off of “what if” or “if this happens” or playing all these scenarios out in my head, it helps. It helps with scanxiety, too.

»MORE: Dealing with scanxiety and waiting for results

Your genetic mutation: ALK+

In lung cancer, there is a pretty short and long list, depending on whom you ask, of how many mutations you can have.

The most common are EGFR and KRAS. Mine was ALK+,which is only in about 5% of non-small cell lung cancer cases. It’s definitely the minority.

When I heard that, I was not happy because I thought there would be no drugs available, and they’d kick me to the curb. I was shocked to find out the contrary.

When I found out I had this ALK (anaplastic lymphoma kinase) mutation, I learned there are a lot of drugs specifically for the ALK+ rearrangement.

That was so encouraging to me! That was the first encouraging bit of news through the diagnosis.

How did you process the cancer diagnosis?

It’s going to sound weird, but I think for me, I didn’t want to show weakness. I didn’t want anyone around me to see how much of an impact it had on me.

Your friends, family, and all your loved ones will halo around you and tell you you’ll be okay. “We’ve got this. Strength in numbers!” You’re like, “Yeah!” I put up this bit of a façade, but inside I was thinking I was going to die tomorrow. That’s how I dealt with it.

It was really hard for me because growing up in sports or in anything in life, you’re always told the harder you work, the better the results. The more you push yourself, whether in the gym or weight room, the more repetitions and time you spend there, you’re going to be successful.

This was the first obstacle in my life where I didn’t have something tangible I could push myself through. That was extremely difficult.

I love to be the driver of my own car. I love to be the person in control of my life. That was such a hard reality for me to face. One of the things cancer does more than anything is take away the feeling of control in life.

Slowly but surely, it was a day-by-day process for me. Once I got my diagnosis, I immediately hit shock and then denial. I thought, “This is not me. This is not going to happen to me.”

Then I started to feel bad for myself. That was probably the darkest time. I had a gap of about 3 weeks from the time I was diagnosed to the time I actually started treatment. Those 21 days were extremely hard, the hardest days of my life.

My life had literally been turned upside down in the blink of an eye. I didn’t transition out of that until I started treatment on June 22nd.

How did you break the news to loved ones?

Pretty early, we decided to share with our family and friends, specifically our immediate family. They had been pretty involved, like my mom, my dad, and my wife’s parents. All of us knew of the situation.

My wife and I waited about a week until we started to tell the rest of our family and friends because when you’re processing something like this, you can never think of the best way to word it, to phrase it. Sometimes you try to give yourself a little bit of time to digest before you start to tell everyone.

If you do it immediately, you can open yourself up to not being able to fully digest it. It’s an important step. You need to understand your diagnosis and your treatment options. If you skip that and go into the next step, sometimes you can take steps back.

Any tips for others on how to share a cancer diagnosis?

Do it on your own terms. I liked the idea of calling my friends and telling them. I felt a little uncomfortable when people will call me or text me or send me messages. You cannot control that, and people just want to help innately.

My best advice would be to find a place where you can gather your thoughts and get away, even if it’s to get away from your spouse, parents, or best friend in the entire world.

Go for a walk or a couple of walks. Go somewhere you can gather your thoughts, think a little bit, and think about what you want to say and how you want to say it, because it is important for you mentally to have an approach.

That was my approach, and that was how we decided that we were going to step forward with this.

»MORE: Breaking the news of a diagnosis to loved ones

Video: Stephen’s Treatment

Treatment (Targeted Therapy)

Did you consider a second opinion?

I did not advocate for myself in the beginning because I have always fallen into the mindset that doctors are the smartest, they know everything, and I just listened to what doctors say. I am so grateful for all the amazing doctors we have in this country.

What I will follow that up with is that it is always a good idea to get a second opinion, even if you don’t think you need one. It’s always a good idea just to get someone else’s advice. I wanted to explore and find out. I wanted to see what else was out there.

Even though there was nothing wrong with my first oncologist, I did get a second opinion. I’m glad I did. The second doctor I spoke with really resonated with me, really spoke things on my level, and helped me understand, giving me so much hope.

If I had never made that decision to reach out and get a second opinion, I think it would have changed my path and my journey. Here I am today, with my same oncologist whom I’ve been with for 3.5 years.

2 oncologists with different treatment recommendations

My oncologist who gave me my diagnosis, who told me to get my port, wanted me to sign up for a trial because before my results had come back, he was almost sure that I was going to be an EGFR mutation. That was based off of my demographics, including age.

He wanted me to sign up for an immunotherapy trial. I felt an immense amount of pressure to agree, to sign up, and to put my name on the paper to get started. I wanted to start.

When I spoke with the second physician, she was a contrarian. She didn’t think I had the EGFR at all and thought I had the ALK+ based off of what she’d seen in my reports. Thankfully, she was right, because it changed my entire treatment course for the better.

I love talking about my treatment course because it was something I had no idea about in targeted drugs, as it relates to cancer patients and cancer journeys.

Targeted therapy drug: TKI (tyrosine kinase inhibitor)

As a completely ignorant young adult, I had only assumed that treatment was chemotherapy or radiation therapy. You did both or one or the other.

My oncologist presented the idea of what’s called a targeted drug, specifically a TKI (tyrosine kinase inhibitor). This was something my family and I had never heard of.

This is an oral drug you take twice a day. It allows me to live a completely normal life. I’ve been on this drug for 3.5 years now and still going. I’m actively on treatment.

To know this drug exists is one thing, but to have it impact my life in such powerful ways is something I’m so grateful for, because this drug was FDA-approved just months before my diagnosis.

It saved my life. It’s truly something I’m grateful for.

How did your oncologist describe the targeted therapy drug regimen?

For non-small cell lung cancer patients who have the ALK+ rearrangement, there was a first-line treatment called crizotinib approved in the early 2010s. It was the first drug of its kind, and it saved a lot of lives.

Then my drug, which is called alectinib or Alecensa, is actually a second-line drug that’s FDA-approved for first-line treatment.

The first time my doctor brought up this new drug, she said this would make me feel better within a few days. Of course, I took that as, “There is no way. I don’t know what the world she’s talking about, but there’s nothing that will make me feel better in just a few days.”

She said I needed to take the drug twice a day, 8 pills in total, and to take them with food. The only thing she said they would do is make me feel a little tired, and I might gain some weight as a side effect. I said, “Sign me up!”

What are the alectinib side effects?

Knock on wood, I have had little to no side effects.

I’ve been on this drug for 3.5 years, so that’s almost 42 months. I was told, sitting in my doctor’s office, that this drug was so new and it worked for about 34 months.

The cool thing is that number keeps moving as I keep moving. I’m a science project. I’m happy to be a science project because I’m still on the drug, and I’m still here.

Thankfully, I’m probably very lucky in that regard. I know some other patients on the medication who don’t take it as well and have to take a smaller dose. For me, I have had no issues.

I will say it is a little toxic to the liver, so I have to get my liver tested every 3 months, give or take. I also have to minimize my alcohol, which is probably a good thing anyway. I can still have a glass of wine, but I can’t have 3 or 4, which is a good thing.

You started feeling great soon after starting treatment

I started my medication June 22nd. I have to be honest, I felt amazing after 3 days. I felt like my old self.

What I mean by that is my wheezing was completely gone. My breathing was back to normal. I didn’t have the feeling like someone was jabbing me in the gut.

I knew then that this drug was working. I could tell it was working. When I went in for my first scan around 60 days after I started the treatment, I had a complete response.

Every tumor on my previous scan had shrunk. Some had disappeared completely. That was the validation I needed that this was working, it would work, and that I have a real chance to beat this.

You were able to go back to work

I started teaching again in August. We start school the first week of August, so life continued. In the South, we start school in August. We don’t wait until Labor Day.

Managing the cancer like a chronic disease

That’s the best way to describe it: I’m dealing with it like a chronic illness. When I was first diagnosed, I had to wrap my brain around this idea of chronic disease.

I’ll explain it in the best way I know possible. Growing up, the only thing I knew about cancer was that you want it out of your body. It needs to be gone completely, cut out surgically, whatever.

When my physician told me because I was stage 4 and because they’d seen cancer spots not only in my lungs but other places like my liver, my spine, my sacrum, and my chest lymph nodes, surgery wasn’t really an option.

Surgery may be an option some day down the road, but for the time being, my oncologist wanted me to not necessarily think that just because the cancer was still in my body. It was wrecking my body.

She said I could live with it. If they could keep the tumors under control, keep them from growing, and keep them stable, I could live a completely ordinary life. I agreed that was a good option when she put it in layman’s terms like that.

I view my disease as a chronic illness that we manage. I hope someday I may be a candidate for surgery or may have some various options, but for the time being, I’m completely satisfied with where I’m at in my treatment.

Paying for the alectinib

When I got the bottle in the mail, of course I had done research and tried to find out everything I could about this alectinib and what it was. I found out that it’s not cheap at all. It is about $11,000 and $13,000 a bottle if you were paying out of pocket.

I’ll be the first one to admit that being a teacher, we have great insurance, and that’s part of the deal. I’m very, very blessed in that regard. I have a max out-of-pocket, which I hit every year. I typically hit my deductible in January, depending on when my first oncologist visit is.

Thankfully, all of my testing was covered. The only thing I can remember that was not covered up front and right away was the foundation biomarker testing. That was simply because my insurance provider hadn’t had a negotiated agreement.

We’re talking about new, innovative testing that can dictate the long-term survival of patients that isn’t necessarily set up yet. We’re still learning about all the genomic sequencing. Thankfully, my insurance provider did end up covering that because that was very expensive.

In the end, I have a small copay of a few dollars for my pills, and it comes every month. I get a call from my pharmacy. They ask me how I’m doing and if I’m ready for a new bottles of pills.

Advancements in lung cancer treatment

In lung cancer specifically, there have been more advances in the last 5 years than there were in the last 50 years. That is so amazing to me.

Anywhere and anytime I can talk about treatment options as it relates to lung cancer in general or just cancer treatments in general, it’s so encouraging.

There’s so much hope. There’s so much to be hopeful for. To think if I were diagnosed 6 or 7 months before, I may or may not have gotten the same drug that I had gotten since.

It makes me even more grateful, so for newly diagnosed patients, whether you’re lung cancer or other various cancers, just take all the old numbers and throw them out.

All the new numbers aren’t reflected yet in terms of what these new treatments can do, specifically targeted drugs and immunotherapies.

Radiation Therapy

When did your oncologist suggest undergoing radiation, and how did she characterize the treatment?

I had a tiny nodule that appeared to be slowly growing. The growth was so slow. It was something like 1 millimeter every 3 to 4 months.

After several months, maybe even a year, of surveillance, we decided to radiate the single node with 5 rounds of SBRT. The radiologist recommended that we radiate the primary or largest tumor as well due to the proximity.

Describe your radiation therapy regimen

I had 5 sessions in total, around the same time every day. After the initial scan to pinpoint the location, my body was marked up with stickers and dots. These were to align me in the exact position for every session.

The only thing that I can remember about the radiation sessions was expecting a laser to drop from the ceiling, similar to something from a James Bond movie. That was not the case!

The treatment itself was relatively quick, less than 10 minutes. Setting up took the longest. My arms would fall asleep from holding them above my head for the entire duration.

It is such a precise therapy, down to something like half of 1 millimeter. The setup needs to be perfect before hitting the big red go button.

What were the SBRT radiation side effects?

Relatively none for me! I did have some fatigue initially, but I did not experience any short-term side effects aside from that.

I did, however, experience pneumonitis several months after the SBRT. Pneumonitis is exactly like pneumonia but without the infection. It is inflammation of the lungs. Each ensuing scan did show scaring and eventually fibrosis.

Around 16 months after this SBRT treatment, my right-middle lobe did eventually entirely collapse. This full collapse is because of the scarring, but it is not as bad as it sounds because we have several lobes, and other lobes will expand to make up the difference.

I cannot tell a difference that I am one lobe short and still very thankful to have several other healthy lobes.

Any guidance on getting through SBRT?

It is not as scary as you may think. I think we are apprehensive about the unknown. For me, that was this preconceived notion that a laser will burn me or cause long-term damage, but my experience was pleasant.

I am still amazed at the precision of these machines. I would highly recommend SBRT to any patient that is considering this as a treatment option.

»MORE: Read other patient experiences with radiation therapy

Video: Stephen’s Reflections

Reflections (Quality of Life)

Being your own advocate as a patient

Sometimes we fall into the mindset that this can’t happen to us or that’s not going to happen to me. For me personally, there’s a self-defense mechanism. When I read about people who are dealing with severe diseases or anything, I tend to distance myself. I put up a halo. I don’t believe it’ll happen to me. It’s not me.

When I started to become symptomatic, I immediately thought nothing was wrong. I kept telling myself that over and over and over. But I knew, deep down, something was a little off in my body.

If I had swallowed my pride, if I had not been afraid of what the actual diagnosis or prognosis would’ve been, I could have probably given myself a little bit better of a position in dealing with lung cancer.

When I could remember those first symptoms, I think about that a lot. What if at that time it was still early stage? What if it was stage 1 or 2, and it was operational? How would that have changed everything? Of course, you can drive yourself crazy doing that as well.

Take that with a grain of salt, but the most important advice I can give to anyone in terms of self-advocacy is that nobody knows your body better than you. It’s so important to seek out answers.

If you don’t like the answers you’re getting or you know they’re not right, try to find someone else.

Walking out of the parking lot in January of that urgent care center, I knew I didn’t have bronchitis. I knew something more was going on there, but at the time, I let the voice in the back of my head not speak up. If I can give anyone advice out there, it’s to step up and find answers. Don’t give up.

»MORE: How to be a self-advocate as a patient

Dealing with the stigma of lung cancer

I love talking about this because being a teacher gives me the opportunity to inform someone who might not be aware of some of these stigmas.

When I was first diagnosed with stage 4 lung cancer, in my own head, I thought I was the bill of health. I was 29 years old. Up until that point, I had always taken care of my body. I had never smoked or anything like that, so to get a cancer diagnosis was so shocking.

To get a lung cancer diagnosis was insane. Completely out of left field. I just assumed because of my demographic, everyone would know it was a freak accident.

Well, that wasn’t necessarily the case. What I mean by that is typically when I share with someone my journey about lung cancer, their first response is, ‘Did you smoke?’

I have no problem with someone asking me that because it gives me the opportunity to educate, but I think that question presents a stigma. We have always been told that you get lung cancer from smoking, that smoking is the only cause of lung cancer, and if you don’t want to get lung cancer, stop smoking or never smoke.

The reality is between 30 and 40% of newly diagnosed lung cancer patients are either never-smokers or have quit for a long, extended amount of time. I think there are a couple different narratives we need to change.

One, we need to change the narrative that lung cancer is a smoker’s disease. We need to address the fact that if you have lungs, you can get lung cancer. Even young never-smokers or not-smokers still get lung cancer.

The second narrative we need to address is that no one deserves lung cancer! It sounds silly, but no one deserves any type of cancer. Even if someone does smoke, I don’t think it’s right morally for me to say that they brought it on themselves.

As anyone who’s in the health industry knows, yes, tobacco is the leading cause of lung cancer, but it’s also the leading cause of other cancers and can contribute to other cancers, as well as other diseases, including cardiovascular.

When you go in to get an EKG or you’re a diabetic, you’re not scrutinized. You’re not asked whether you smoked or, “Did you bring this on yourself?” The narrative needs to shift.

As a human race, we need to empathize with lung cancer patients. We need to say, ‘Whether you smoked or not doesn’t matter. ‘

We just need to support you, and we need to understand that lung cancer patients need research and treatment options, just like every other cancer patient does.

How was it being an adolescent young adult (AYA) cancer patient?

The first thing I did was I scoured the internet trying to find some stories of hope. I wanted to see someone beat lung cancer, and it’s hard.

It’s hard in our lung cancer community to find those things, or maybe it was when I was first diagnosed. It’s getting much better. The reason is when you look at the statistics of lung cancer, specifically late stage or stage 4, it’s not very encouraging.

When I was diagnosed, I was told the survival rate was about 16%. When I heard that, that was very discouraging for me. That was about 4 years ago.

Now, it’s already up to 21%, which is highly encouraging. It’s not where we want it, but it’s great. It’s because of these new therapies and new drugs.

When I think about a newly diagnosed patient and advice I could give them as far as finding a community, there’s a lot of great resources out there now for lung cancer that weren’t available when I was diagnosed.

Finding those resources, which can be located on various lung cancer nonprofits, but also finding a group or individuals who have walked the path. For me, that was through social media.

If I can see someone has done something, beat a cancer, or they’ve lived 5, 10, 15 years with cancer, that gives me hope.

I can ask myself, ‘If they can do it, why can’t I do it?’ I think that speaks volumes to the mind, the mental game of beating cancer.

How did you plan for the future (family) while dealing with a late-stage cancer diagnosis?

One thing I love to talk about in my journey is starting a family. Receiving my diagnosis, talking about my medication and my treatment options, the last thing on my mind was starting a family.

My oncologist, whom I love dearly, told me she wanted me to think about the option or at least have the option to start a family, because once we started this drug, I wouldn’t be able to naturally conceive.

I looked at her like she had 3 eyes. I was like, ‘You think that’s what I’m thinking about right now? All I’m thinking about is living tomorrow. I just want to make it.’

My wife and I went home and talked about it long and hard. It was something I didn’t have any interest in, but I am so grateful that we made the arrangements.

About 2 years into my journey with lung cancer, after several good stable scans, life started to feel much more normal than I would have ever expected. I think it’s because when you are handed a diagnosis, your life just flips upside down.

Doing things that got me back into a routine, like work, traveling with my wife, doing family get togethers, and going and doing things with my friends, slowly but surely I started to feel normal again. I got to a point after 2 years where I felt normal enough to explore the options of starting a family.

Thankfully, I am so grateful that I did. If I had been as stubborn as I was with my diagnosis and I didn’t have someone advocating, I might not have had the chance to make those arrangements.

We welcomed our son into the world, scientifically, through IVF in January. He is healthy, he is happy, and he is the light of our worlds.

Describe how you approached fertility preservation

Right before I started taking my targeted drug, alectinib, my oncologist said if I wanted to eventually start a family, I wouldn’t be able to while on the medication.

She highly recommended I go to a fertility clinic and do the sperm bank just to have the option down the road.

»MORE: Fertility preservation and cancer treatment

That’s when my wife and I went home and discussed it. I was not into the idea at all. That was the last thing on my mind. I was so angry that I couldn’t even think about it.

Thankfully, I let it sink in for a few days, and I did it because my wife was advocating. She said she knew it was something I didn’t want to think about right then, but she really thought we should do it. And we did.

My son is technically 3.5 years old! The really cool thing about the IVF process is when they create the embryos, we have multiple viable embryos. We still have a couple that down the road, if we decide to make another addition to the family, we have that option.

»MORE: Read a patient’s detailed IVF journal

What does survivorship mean to you?

Survivorship to me is not letting cancer win. What I mean is not necessarily winning in terms of where it is in my body or if it’s growing. I mean winning by taking away the joy I want to live my life with.

Every second that I spend thinking about, ‘What if? How will this affect me? What if this gets worse?’ is the second I’m letting cancer win.

By focusing on all the things I want to do in life and how I want to live, being a happy, loving father and husband, being a joy in life, that’s winning. That’s survivorship to me.

If I’m having a bad day or feeling down, I get out of the house and do something. I hit the reset button. It’s okay to cry. I tell people that all the time.

It’s okay to feel bad and cry, but you have to get out of it. Flip the switch at some point to stop feeling sorry for yourself, and turn adversity into an opportunity.

I try to turn adversity into an opportunity to be a light, share my story, to advocate for cancer and lung cancer specifically, and live life for the fullest.

Last message to patients

My last message would be that for me, personally, my cancer diagnosis in a weird, obscure way was a gift. I wouldn’t give it to anyone and wouldn’t wish it upon anyone else, but the only reason I would call it a gift for me is because it has helped me recognize and appreciate life much more so now than I ever did before I was diagnosed.

For that, I am so grateful because I try to live every day as best as I can. My diagnosis brought that out in me. For newly diagnosed or people who’ve never been diagnosed, don’t wait for something like that to happen to you, to live that way, to live the way you want to live.

I tell my school kids every day a saying we put on the wall. It’s corny and cliché, but it’s so important to me. It’s 3 letters: A, I, E.. It stands for “Attitude is everything.”

To me, attitude is the most important thing in life. Like Henry Ford said, whether you think you can or whether you think you can’t, you’re probably right.

That resonates so well with me because attitude directs you in life and how you view things. It gives you perspective. It gives you the opportunity to look beyond your circumstances and to help others.

Inspired by Stephen's story?

Share your story, too!

Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Stories

Maggie M., Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, EGFR+, MET Amplification & Overexpression, Stage 4 (Metastatic)

Symptoms: Ocular migraines (kaleidoscope vision), partial blood clot (DVT) in the leg, vision and balance problems, minor chest pain

Treatments: Targeted therapy (tyrosine kinase inhibitors or TKIs), radiation therapy (stereotactic body radiotherapy or SBRT), clinical trials, chemotherapy (combined platinum-based regimen)

Clara C., Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, ALK+, Stage 4 (Metastatic)

Symptoms: Pelvic pain and discomfort, bladder issues related to pelvic tumors, incontinence, pain in the lower back and hip

Treatments: Chemotherapy, immunotherapy, radiation therapy, targeted therapy (lorlatinib)

Shira B., Lung Cancer, EGFR+, Stage 1B

Symptoms: None per se; discovered during a preventative full-body MRI

Treatment: Surgery (thoracotomy)

Phil P., Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, ROS1+, Stage 4 (Metastatic)

Symptoms: Persistent cough, nasal drip, shortness of breath, inability to speak in full sentences

Treatments: Chemotherapy, targeted therapy, radiation therapy, next-generation ROS1 inhibitor (clinical trial)

Stephanie K., Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, ALK+, Stage 4 (Metastatic)

Symptoms: Persistent and intense cough, general feeling of sluggishness

Treatments: Chemotherapy, targeted therapy through a clinical trial, radiation therapy