Jeff’s Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL) Story

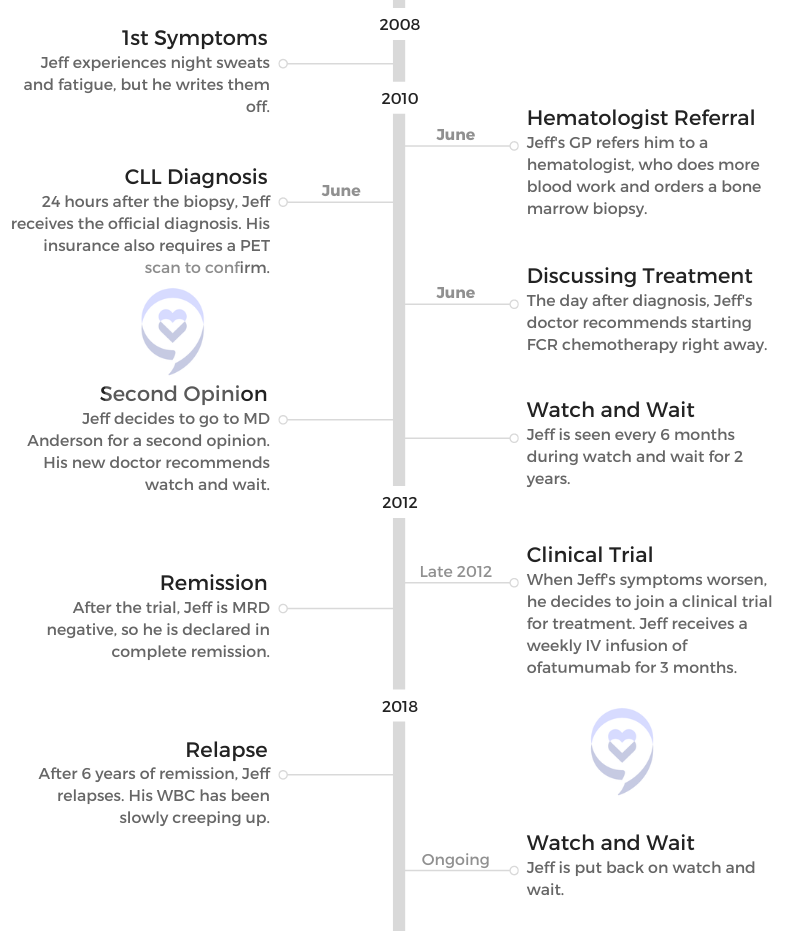

When Jeff started experiencing fatigue and night sweats, he didn’t expect to be diagnosed with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

Jeff’s story includes undergoing watch and wait, joining a clinical trial, reaching remission and going back on watch and wait.

Along the way, Jeff learned some important lessons that he shares with us: getting a second opinion, cutting out unimportant things and finding humor in all situations.

Thank you for sharing your story, Jeff!

- Name: Jeff F.

- 1st Symptoms:

- Fatigue

- Night sweats

- Diagnosis (DX):

- Chronic lymphocytic leukemia CLL)

- Testing for DX:

- Blood work

- Bone marrow biopsy

- Treatment:

- Watch and wait

- Clinical trial

- Ofatumumab infusion

- The CLL Diagnosis

- Living with Cancer

- Clinical Trial Experience

- Joining a Clinical Trial

- Time for treatment for CLL

- Why did you decide to do a clinical trial?

- Later in a clinical trial, what are the other considerations and questions patients and care partners should be asking?

- What is the human experience of a clinical trial?

- Reaching remission

- Did you know if this was a blinded study?

- Meaning dose?

- Reflections

- Joining a Clinical Trial

- More CLL Stories

This interview has been edited for clarity. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider for treatment decisions.

Go live a great life, because it absolutely is possible.

The CLL Diagnosis

Introduction

Tell me about yourself

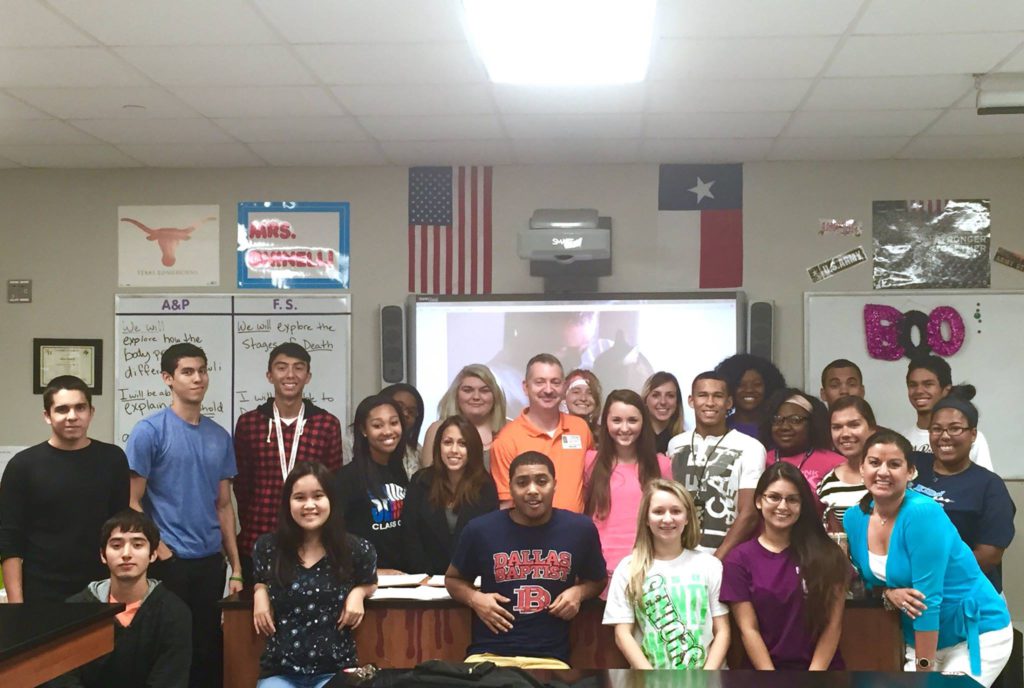

I always start off by telling people that I am a very shy introvert. I count to 3, and then I start laughing because that is 180 degrees opposite of what I truly am. From a very young age, I have been a public speaker. I loved being on the stage and connecting with people, and that’s one of the things that gives me a ton of pleasure. I continue doing it to this day.

As far as the best part about me, I think I have the most awesome daughters and awesome wife in the entire world. My family has been absolutely wonderful throughout this — we’ll call it a “journey.” It’s not a journey. It’s a pain in the butt. They’ve been absolutely great, and I love the fact that we have so much closer of a relationship now. I’m going to say that’s partly due to CLL.

What were your first CLL symptoms?

I was in my mid-40s at that time, and I just thought things were normal. I had some family history of some issues — some high blood pressure, some high cholesterol — and I was seeing my doctor regularly to keep that managed and under control. I like to use the term being a “compliant patient” [for] following those instructions.

I really didn’t notice that the symptoms I was having were out of the ordinary. I love Thai food, and I eat a lot of Thai food. Occasionally, I would get night sweats. I was thinking, “Hey, that’s just eating too much spicy food before I go to bed.”

I was tired all the time, and I was like, “Okay, this is what it’s like to be male hitting midlife, and you run out of energy.” It turned out that was wrong.

I’m very fortunate that my GP, who I still see every 90 days, was keeping tabs on things. He said, “Look, something’s wrong. I don’t know what that something is, so I’m going to get a pinch hitter. I’d like you to go see a hematologist, and let’s find out what’s going on.” And that’s what I did.

The CLL Diagnosis

What was the first indicator to you that this is something very serious?

Unfortunately, I remember exactly how I felt throughout that entire process, because it was a part of my life where everything changed in a very compressed period of time. My GP said, “I need you to go see a hematologist.”

I was like, “No problem. I see specialists all the time.”

He said, “I’m going to make the appointment for you.”

Okay, fine. The appointment was made for the next day. Great. Not a problem. I was doing okay right until I got into the hematologist’s office. I didn’t think that cancer was a possibility, and I didn’t think anything major. It was, “My doc wants to check off some boxes.”

Literally, it was like somebody had taken a baseball bat, swung at full speed right into my gut, and just took all the air completely out of me.

Seeing the hematologist

When I walked into the hematologist’s office, everybody in there was old, ugly and sick. That’s what it looked like to me. I realize that sounds like a generalization, but I’m thinking to myself, “What in the heck are you doing in this office?”

[I] got ushered into the back, and the hematologist looked over the blood test results that my doctor had sent over. He said, “Nope, I want to do this myself.” They drew some blood, and he said, “Nope, this is not good. I need you to come in tomorrow. Bring your wife. She’ll have to drive you home. We’re going to do a bone marrow biopsy.”

I can give you a really detailed description of what a bone marrow biopsy is, and I guarantee you you’ll feel it after I tell the story. But the TL;DR (too long; didn’t read) is you lie down on your belly, they shove a corkscrew in your hip, and they pull out a bunch of tissue.

Then 24 hours later, I learned that I had leukemia. In a period of 48 hours, I go from being a tired, middle-aged dude to, “You’ve got cancer.”

What was your reaction?

The moment was a phone call from the doctor, not the doctor’s nurse. He had reviewed the bone marrow biopsy results, and he said, “I would like you to come back into the office with your wife.”

I said, “Well, I kind of know where this is going. Why don’t you just tell me what’s going on?”

He said, “No, that’s not how we do things here.”

I said, “This is how we’re doing things here. I promise I’ll come in tomorrow, but I need to know what’s going on.”

He said, “Mr. Folloder, you have leukemia, and you need to come in tomorrow so that we can discuss how we’re going to treat it.”

Literally, it was like somebody had taken a baseball bat, swung at full speed right into my gut, and just took all the air completely out of me. My wife and I freaked out — and I still get misty about it — but we kept our word.

»MORE: Patients share how they processed a cancer diagnosis

Discussing treatment for CLL

We went to the doctor again the next day. He scribbled some things on a pad, and he tried to explain what chronic lymphocytic leukemia was and why it was an important cancer. Then he said, “We need to start treatment right away.”

I was like, “Wait, wait. I’m just a little bit tired. Why do we have to start treatment right away?”

He said, “I want to put you on what we call the gold standard of care,” which was a combination therapy called FCR that was very popular at the time and is still used somewhat today.

I started taking very deep breaths. Then for whatever reason, he decided that it was important to tell me that I should expect to live 6 years. That’s when I stopped breathing heavily.

I was like, “Okay, this is a lot to digest. My wife and I are going to head home, and we’re going to talk about this. We make decisions as a team.”

Patient-Doctor Relationship

Deciding to get a second opinion

We got home, and we started talking. I looked at my wife, Penny. I said, “He’s fired.”

“Wait, what? What?”

“He’s fired. I’m not going to work with anybody who’s putting an endgame on my life right now. I don’t feel comfortable with this guy.” We’ve got friends and family that work at one of the greatest cancer centers known to the entire universe. It was time to get a second opinion, like right now.

‘You may die with this. You’re not going to die from this. What we’re going to do now is absolutely nothing.’

Jeff’s 2nd Doctor

I called up my aunt, who worked there at the time, and told her what was going on. I said, “Look, I get it. The diagnosis is not going to change.”

She said, “Well, you’re probably right about that.”

“But where you are, the treatment options are huge. I want to make sure that the treatment that I get is the right one for me, so can you get me a hookup?”

It’s very bizarre for a mid-40s somebody to be asking a mid-60s aunt to “get me a hookup. I need to see the right doctor.” But that’s exactly what she did. Literally that same week, I got into that hospital, and I saw one of the world’s leading experts on CLL. My entire trajectory changed for the better.

Can you describe the concept of firing your doctor?

Not every doctor has the best training in how to communicate with patients. Some do it much better than others. For me, having a sincere, candid conversation that’s not dismissive is crucial to me being able to relate to the doctor and to be able to be that compliant patient.

My doctor, that first one, had basically already written me off. In my playbook, that wasn’t going to work. In the communities that I help lead and help advocate for, we tell everyone, “Your doctor can be great, but you have to get a CLL specialist on your team.”

He doesn’t have to play the lead. She doesn’t have to play the lead. But you owe it to yourself to get a CLL specialist as part of the team. Even though your local hematologist may mean well, they’re seeing every type of blood cancer patient.

A CLL specialist, that’s it. All they do is CLL, and getting that perspective can be life changing and mind changing.

To put a really bright underline under that, the person that I saw at this giant hospital in the Houston area asked me, “What did the first doctor want to start you on?”

I told him, “He wants to start FCR right away.”

He said, “That’s really interesting.”

I said, “Why is that interesting?”

He said, “I helped invent the FCR treatment. I know all about the FCR treatment. It’s a really good treatment, and yeah, he’s right. It’s a gold standard. But it’s not right for you.”

I took a really deep breath, and I was like, “Okay, this doctor is really out there in terms of how big his ego is.”

“I invented it.” That’s kind of cool. But he was able to bring me down to a calmer place. “We’re not going to do that because I don’t think it’s right for you.”

I was like, “What is?”

He literally picked me up off the chair, gave me a hug, and said, “Look, you may die with this. You’re not going to die from this. What we’re going to do now is absolutely nothing.”

I was like, “Hold on a second. It’s cancer. We’ve got the early diagnosis. What about the whole program — find it early, attack it hard, go after it, then go live your life?”

He said, “Yeah. Sorry. Not how this disease works. We’re going to keep eyes on you, we’re going to keep eyes on your blood, we’re going to keep eyes on your symptoms, and we’re going to keep eyes on, ‘How is Jeff doing? How is Jeff living?’ We are here to help you have the best possible life, so we’re going to monitor closely. When it’s time, we’re going to treat you with the best thing that’s available for you at that moment.”

That’s exactly what I needed to hear. That’s the kind of doctor relationship that I needed. Tell me what’s going on. Don’t pull any punches. Make it personalized. At least connect with me as a human being to make sure that I understand you get it. Living a great life is important. That was a big deal.

He also picked my wife up out of her chair and hugged her, and she was like, “Wait, why am I getting this hug?” But be that as it may.

Working with both your local hematologist and a large cancer center like MD Anderson

That is a very common setup. There are great cancer centers all over the United States — all over the world, actually. A lot of them are just doing amazing research and doing some really cool clinical trials and good work to connect with the CLL community. They do realize at their core that as hard as we try, as great as some people’s insurance is, it’s just not possible to make that physical trek to a center of excellence, if you will.

Most of the professionals that I’ve talked to in my patient advocacy work refer to it as the quarterback scenario. The local guys, the local gals — they’re the team. They’re the ones who are meeting you face-to-face and making sure that your care is done on a regular basis.

The CLL specialist absolutely can be seen every now and then, or just once to call in a play to make sure that your local people are on top of what the latest and greatest are. I know lots of people who do just that, and they’re getting great care.

The importance of finding the right doctor

It is something that does have a long-term element. I’m couching my words very carefully right now, because when I was first diagnosed, nobody used the word “cure.” [It] was not part of the language of CLL. Here we are, a dozen-plus years down the line, and for a bunch of subsegments of CLL, the doctors are now starting to toss that word around: “cure.”

This could be a long time, but for some of us, that could still be a finite long time. We see the end of that road. It is really, really important to connect with your doctor as someone that you can get along with. I remember very early on, I was connected with a person on one of the Facebook support groups who wanted to come to the Houston area and meet with the same doctor that I was seeing at MD Anderson. I thought it was great.

I said, “Look, I know this is going to be scary because you’re coming in from Florida and this, that, the other thing. I’ll tell you what, I can carve out some time. I’ll come meet you at the hospital. I’ll sit with you while you’re waiting to see them. We’ll chat and we’ll get some lunch.”

She did the appointment. She came back out. I went, “How did it go?”

“Can’t stand him.”

I was like, “Wait, what?”

“No, he and I? No, this is not going to work.”

“Tell me what you don’t like,” and she did. I said, “I got this one,” and I wrote a name down on a piece of paper. I said, “Not right now, [but] when you get home, call this doctor. Sorry, she’s not in Florida. She’s up in New York, but I think you’ll get along great with her.”

Sometimes you don’t make that connection the first time. Even if you’re seeing one of the greatest CLL specialists in the world, the personalities may not perfectly mesh. Keep trying. It may take 1, 2, 3, 4 appointments, but you have to find somebody that you can be comfortable with, because this is going to be a long-term relationship.

»MORE: How to be a self-advocate as a patient

Living with Cancer

Watch and Wait

“Watch and worry” or “worry and wait”

The patients and their caregivers are not nearly as polite about it. “Watch and wait” is on the borderline of being sarcastic because sitting there doing nothing is so 180 degrees from what everybody has been told about cancer for their entire life.

While you’re in watch and wait, you may be watching. You may be waiting. But you’re worrying, and you’re freaking out about every single, solitary thing because anything that goes wrong, you [think], “That must be the cancer. That’s the CLL kicking in. I’ve got a rash. Ooh, that must be CLL. I can’t do this. Must be CLL.” It becomes this waterfall that you just can’t escape, and it’s constantly beating on your head.

Can you explain getting through knowing you had cancer but not treating it?

I think the best word that I can use to describe watch and wait or conscientious surveillance is that it’s “oppressive.” That’s the best word that I can use for it, because every day you do have to parse all the things that you’re feeling and figure out what can be dismissed as just being normal and what is actually salient that you need to communicate to your team.

Every time you go to have a meeting with the team, they always tell you, “We want to know everything. Don’t leave anything out.” Of course, I started this off like every typical male patient ever does. I would go in for my regular appointment. In the beginning, I always brought my wife with me. The nurse practitioner would come in. The first question that was asked was, “So, how are we doing today?”

My typical male response was, “Fine,” and I left it at that silence.

“So you’re doing okay?”

“Yeah.” My wife [was shaking her head] back and forth.

“Ma’am, you want to tell me what’s wrong with your husband?”

It’s learning how to get past the, “I’m a strong man. I can’t show any weakness,” to, “Okay, I got some crap going on. Here’s what’s happening. What do I need to be worried about?”

As we progressed through not just months but years of that watch and wait, I learned how to be a better communicator with my doctor, with the mid-level practitioners and with my wife about, “Okay, this is important. This is not so much.”

What helped you with the oppressiveness of watch and wait?

I am what most would consider a Type A personality. Add on a soupçon of OCD, and you have a really good description of how my life has been. My biggest problem right up until my cancer diagnosis was that I was an inveterate list maker. I would make tons and tons of lists of all the stuff that I had to get done: stuff I had to get done short-term, mid-term, long-term, plans. This, that, the other. That’s how Type A people are.

The oppression of watch and wait combined with that was not a good mix. As a matter of fact, it was somewhat toxic, and I was getting very frustrated with myself. [I was] getting very frustrated with my family, getting frustrated with my cancer, and getting frustrated that everything was conspiring to make sure that I didn’t get stuff done. Quite frankly, that sucked because that’s not how I had lived my entire life, and I’m not exactly sure what all came together.

It was probably about a year into watch and wait when I came to the realization that I simply couldn’t do it all anymore. It’s not that there wasn’t enough gas in the tank; it’s that I didn’t have enough bandwidth to do everything all the time, 24/7, anymore because things had changed.

I did pull out one of those classic bright yellow legal pads, and I drew a line down it. On the left was stuff that I keep, and on the right was stuff that I throw away. I literally made a big important list that said, “This is all the stuff that’s worth doing. This is all the B.S. that just doesn’t deserve my time right now.”

I stopped doing that B.S. stuff. I cut a bunch of stuff out of my life, and I told people and commitments, “Sorry, you’re on your own.” I had to claw back time for myself. That is how I dealt with watch and wait. I was able to pull up the parking brake and do something that not many people get an opportunity to do, which is reevaluate your life, throw away all the bad stuff and focus on the good stuff.

Did you cut out relationships and tasks that weren’t meaningful?

It’s all of the above. An example would be: most Type A OCD leaders believe that the best way to do a job is to do it yourself. I wound up doing everybody else’s job in addition to doing my job, and that came to a crashing halt.

“Well, here’s the deal. I hired you to do this job. Do your job. If I don’t like the way you’re doing it, I’ll find somebody else to do your job.” That sounds very perfunctory, but it was a life-changing moment for me because I no longer took it personally. If someone that I worked with failed, it wasn’t my fault. It’s their fault. I could put that on the “do not do” side of the list and make it go along.

Having a mindset change

I was traveling a lot for work. This was long before COVID, everybody discovering Zoom and teleconferencing, and all that stuff. I stopped doing a lot of the traveling. I started taking more time to do the things that made me smile.

[It could be] something as simple as instead of getting on a plane and flying to Atlanta, jumping in the truck, driving, actually enjoying the drive and seeing the country. Put on some jazz. Smoke a cigar while I’m driving (don’t tell the doctors). Have a good time. It was a mindset change where the important stuff is important.

Let’s make sure I have enough energy to do the important stuff instead of shortchanging the important stuff. Things like dealing with neighbors’ problems. It used to be, “Hey, I’ll get this taken care of for you. I know who to talk to.” No, not on my list anymore. I realize that a lot of this sounds trivial, and it is trivial right up until you realize how much time and energy you’re wasting on a lot of that stuff.

Asking for Help

How does financial toxicity affect people?

The financial toxicity side of this is the biggest fear stop sign that I deal with in these support groups. Everybody is really, really jazzed about the fact that we’ve got so many new, good, effective treatments coming. Everybody’s really, really thrilled about the fact that side effects are easy to manage. They’re really, really pumped about the fact that access to these is becoming more and more widely available.

What takes the wind out of their sails is $4,000 a month, $10,000 a month, $13,000 a month or $27,000 for a bag of medicine. People wonder how they’re going to get that bill covered because there’s so many different questions. We don’t have enough time. We don’t have enough energy. There’s not enough gas in the tank to debate the health care system.

Medical insurance, at least in my mind, is not insurance. It’s a way to spread the payments over a lifetime. Some people have programs like that. Other people don’t. I struggle with that because I know that there are patients who could be helped who can’t access that help for want of money.

Not knowing about assistance programs

There are programs out there, foundations, associations, nonprofits and even the drug companies themselves. All of them have a whole bunch of fabulous programs that can help people with the financial burden. The big problem is people don’t hear about that until long after they get the price tag upfront.

There’s no shame in saying, ‘Yes, I need some help.’

You get the shock, you get the freak-out, and you get the, “Oh my God, I can never do this.” Then maybe you’ll get information about how you can cover shortfalls down the line, or maybe you don’t get that information and just walk away.

That’s disturbing and upsetting for me because, yes, I believe that everyone should have access to this medicine. That doesn’t always come through right now. I want everybody to be helped, and I can’t help everybody.

What are some of the assistance programs?

The first 3 that I bring up:

- The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society (LLS). These folks have great education programs. They have great learning programs. They put a lot of stuff on the plate, and they also have patient assistance programs. People can apply for these programs. They open and close regularly, and most of them don’t even have an income barrier. Sign up, and you get an LLS gift card to help defray your costs.

- The PAN Foundation is a great group of people who do nothing but make sure that people who need patient assistance get patient assistance.

- Then the third one, which I think is the most important one: the drug companies themselves. Everybody forgets to go ask the drug company. Quite frankly, although we’re talking about this in terms of cancer, any medication that you’re prescribed that doesn’t have a generic, I always recommend [to] go to that company’s website. Chances are there’s a copay assistance program available for you. They’re there, and they’re available.

If somebody wants to give you $10, $50, $1,000 or $10,000 to help you with your treatment program, take it. There’s no shame in saying, “Yes, I need some help.”

What’s your message to folks who are nervous about asking for help?

This is critical to a successful patient experience. If you’re male [you think], “Everything is okay, and nobody’s going to see me being vulnerable.” It doesn’t quite work. I know it’s part of being a guy, but it just doesn’t quite work. This is heavy stuff. This is big stuff, and there are people that can help you with that big stuff.

I was having a conversation with a gentleman who actually, of all things, was my life insurance salesman and is still my life insurance salesman at this time. I had let Keith know that I had been diagnosed with leukemia. We talked for a bit, and he said, “You probably need to call these folks at CanCare.”

I was like, “What’s CanCare?”

He said, “They’re a really cool support group.”

I was like, “No. Stop. I’m not sitting around in a circle singing Kumbaya with everybody and learning how to pass a peace pipe. No, not going to do that.”

He said, “No, they do things a little bit different. There’s no group support thing that they do. You call them up and let them know what’s going on, and they match you one-on-one with someone who’s just like you that’s gone through what you’re going through.”

I thought to myself, “That’s not bad. That sounds doable.” I called CanCare up, and I got connected. Lo and behold, I acquired a CLL Sherpa, and this person was like me. My age, male, same goals, family and all that stuff. He’d been there, done that and got the T-shirt.

Getting rid of some of the burden

It was great to be able to talk to somebody who knew what I was going through. Frankly, that’s getting rid of a burden. Watch and wait — it’s oppressive enough having cancer. It’s oppressive enough. Going through all of this is oppressive enough. Being able to get rid of some of that burden is a big deal.

If things aren’t going 100% right, let the team know. Let your significant other know. Let your best friend know. Let somebody know, because you can get help, and you don’t have to do this by yourself.

Clinical Trial Experience

Joining a Clinical Trial

Time for treatment for CLL

I can remember the appointment that I had at Anderson when we were going through that evaluation. I said, “Yeah, the fatigue is beginning to kick in.”

They asked me, “Well, what does that mean?”

“That means that I’m crashing a lot earlier and a lot harder than I used to, and I’m missing out on some stuff.”

“What do you mean, you’re missing out?”

“I can usually stick it out, have an extra cup of coffee, maybe throw down a chocolate bar or something like that, and get everything done that I needed to get done. Now, sometimes I go, ‘This is going to have to wait because I don’t have enough gas in the tank.'”

That’s when my team went, “Okay, it’s time for treatment.”

I wanted to say, “Wait, all I had to do was say that earlier, and we could have started treatment?”

“No, we needed you to be honest, and you’re being honest.”

It was the combination of my blood work, my symptom load and my quality of life. That matrix all came together, and it was time for treatment.

Why did you decide to do a clinical trial?

For many, clinical trials are this big, scary thing that sounds like, “I’m going to be a guinea pig. I’m going to be a lab rat.” I’ve since learned that’s somewhat of a misnomer. A lot of times when you’re offered the prospect of a clinical trial, it’s not very on early in the clinical trial. It’s down the line.

As it was explained to me, “This will give you the opportunity to get access to medicine that we already know is going to be beneficial. We’re just fine-tuning it at this point. It will be as good or better than the standard of care.”

When it was presented to me in that way, my next question was, “So what happens if I get the placebo?”

“There’s no placebo. You’re getting the medicine. Downside: you may experience some side effects, but we think those side effects will be less than the standard of care.”

They need to be able to connect with patients who are the right targets for that treatment.

I said, “Okay, sign me up. I’m in.”

Then a nurse walked in with a stack of about 6 inches of informed consent that I had to go through. That was a bit of a nightmare. I was completely comfortable with my doctor, who had already demonstrated his prowess by saying, “I invented FCR. We don’t do FCR for you. We should do this because it’s going to give you the best shot at a complete remission for the longest period of time with the least amount of side effects.”

I want to ring this bell one more time: the fact that I was getting this message not from a generalist, but from a CLL specialist. This is somebody who eats, drinks, sleeps, breathes CLL 24/7. That doctor sees more CLL patients in a day than most generalists will see in a year. That has gravitas.

»MORE: Read more on FDA approvals of clinical trials

Later in a clinical trial, what are the other considerations and questions patients and care partners should be asking?

The very first question that they should ask is, “What’s this going to cost me?” We have to be candid. Medical research is really, really expensive, and it doesn’t always yield success. There’s a lot of swinging and missing that Big Pharma is doing in order to get a successful treatment.

When they get further down the line — stage 2, 3 and 4 of their clinical trials — they’re getting to points where we’ve got this. We’re just rounding this corner. We’re sharpening this edge. They need to be able to connect with patients who are the right targets for that treatment.

Like you mentioned earlier, CLL is not the most common cancer out there. In the United States, maybe there are 15,000 new diagnoses in a year, and you’ve got a couple of drug companies trying to create a drug for a small subsegment of them. Treatment sounds really, really good, but if I can get it for free, that sounds even better.

Even though I had great insurance at the time, quite frankly, my insurance company (me) didn’t have to pay for the drug. All we had to pay for is the administration of the drug. That’s a huge consideration.

We talked about CLL not being the most common cancer. We talked about medical research being expensive. Being able to pay for the medicine is a really important consideration. Sometimes a clinical trial is a great way to sidestep a huge chunk of that expense.

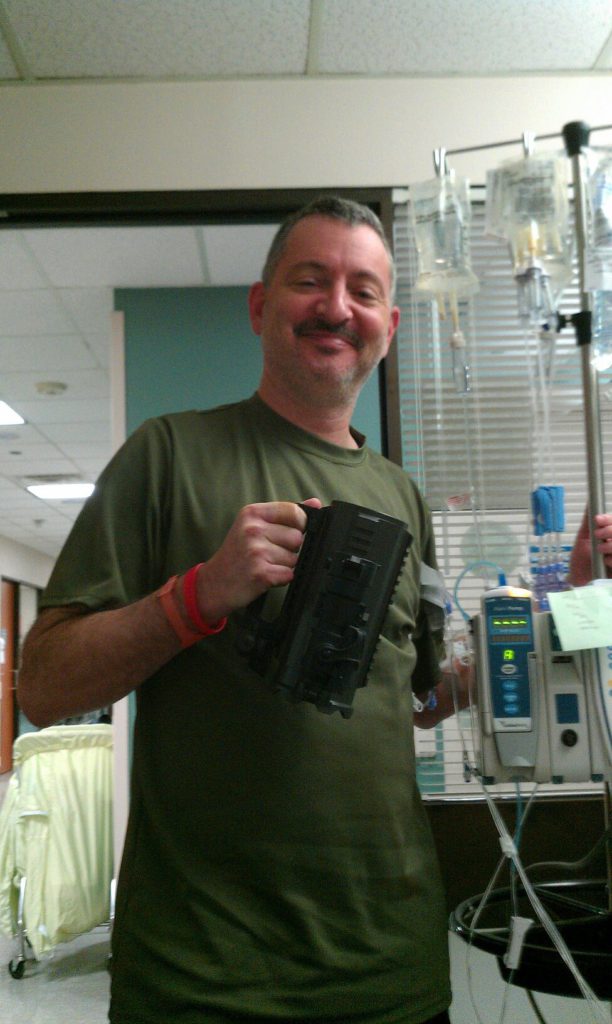

What is the human experience of a clinical trial?

I thought it was going to be very lab ratty, even though I knew up [in my head] that I wasn’t going to be one. In [my heart] I was still scared. I did everything in what’s called the Ambulatory Treatment Center at Anderson. I would show up on a very regular basis in a room that was slightly larger than my walk-in closet and get plugged in. I would get my IV going, and we’d get all the pre-meds and all that stuff.

The first time around was a harrowing experience because they kind of couched what would happen. They said, “You should expect your first treatment to go about 8 hours, because your body has to get used to this stuff. There’s going to be some adverse reactions. When those happen, we have to stop what we’re doing, treat your reaction and then start all over again.”

Yeah, 8 hours turned into like 23, and I exhibited most of the adverse reactions to the treatment that were on the list from all that informed consent. It’s very disturbing to wake up out of a Benadryl-induced stupor to have your wife saying, “You’re a tomato,” and you’re solid red. Now you’ve got spots, and now this, and now that.

All that happened, but they treated me like royalty. At no point did I feel like I was in danger. I was getting the best of care. It got to the point where I could drive myself to the Ambulatory Treatment Center. I could get plugged in by myself. I could get the treatment. I could get the saline flush, and I could drive myself out. It became routine.

I was thinking to myself, “Well, even if this doesn’t work, they’re going to find out what didn’t work. Those are more data points. It’s not hurting me, and I stand a really good chance, according to my doctor, of getting a complete remission. Let’s stick with this.”

I did, and amazingly, I did achieve complete remission. I got the coveted MRD, minimal residual disease negative, for 6.5 years without having to go through traditional chemo. That was, I believe, worth the price of admission.

Reaching remission

Everybody was learning along the way. I’ll circle back to earlier when we talked about me being the compliant patient. Of course, as part of the clinical trial, they said, “Would you mind giving up all these additional tissue and blood samples during the trial so we can check this, that and the other thing?” Of course, I said yes.

Did you know if this was a blinded study?

In this clinical trial, everyone who was participating in the trial was receiving the medicine. They were not receiving standard of care. It was a fairly down-the-line clinical trial. Everybody was going to get the medicine. We need to see how different karyotypes react to the treatment and at what treatment level.

Meaning dose?

Dosage response. Is it a partial remission? Is it a complete remission? Is it MRD negative?

A few minutes ago, I was bragging [about] 6.5 years of MRD negative. I probably am not supposed to know that was one of the best responses in the clinical trial, but it was. And 10 years later, it doesn’t even bear asking why that happened, because we’ve moved past that already. We’ve already got so many cool new drugs.

The folks at Anderson were plotting out that bell curve and going, “Okay, Jeff is trisomy 12 mutated [and] all these combinations. He got 6.5 years. This person was this type; they got 1 year. This person [had] no response at all.”

All that information is important because they were studying a treatment mode that was far less toxic than the standard of care. FCR is a combination of chemotherapy and monoclonal antibodies. What I did was exclusively monoclonal antibodies, because somebody said, “If you’ve got a high expression of this CD20 marker on your cells, this stands a really good chance of knocking that sucker out.” It did for me, so great on the data point.

Editor’s Note: In the clinical trial, Jeff received an IV of ofatumumab.

Reflections

Using humor to deal with cancer

I have this bright red shirt with white letters, and on the front of it, it says, “Sarcasm. It’s how I hug.” My family knows that that is true. If I can’t find something to laugh at, you know things have gone really, really bad. I am going to find something to smile [at]. I am going to find something to laugh at. I am going to find something to dial down the tension. Otherwise, the oppression just gets to be too much.

Sometimes the humor is inappropriate. I will admit that right now. I can remember the word choice that I used when my daughter came into the Ambulatory Treatment Center with a bag full of Chick-Fil-A nuggets. “Honey, you can’t have those here.” That’s the paraphrase. I gave her the full-on of why having the fried chicken smell where people were receiving treatment is not a good idea. I may not have used the best choice of words, but we did laugh. So there’s that.

Making life changes

After I was pronounced MRD negative, complete remission, I was like, “Huh. I got my life back.” I kind of realized there was a quid pro quo that was expected at this point. I had gone through an awful lot. I had done an awful lot.

I’ve got a reset button that got pressed. What am I going to do with it? For the first time in my life, I decided perhaps it’s time to start taking better care of my body. I have been thin and relatively fit for most of my life, despite my family history of heart disease and all that happy stuff.

I started exercising. My wife had been a wonderful care partner throughout my treatment, the diagnosis and everything leading up to MRD negative. But she didn’t take very good care of herself while she was doing this, and she got big. She got very big. For someone who’s 5’4″ and that big, it was not healthy.

I got to MRD negative. I turned around, and (of course, with a bit of sarcasm) I said, “We can only have one health care crisis in this house at a time. Mine’s done. Let’s work on you.” My wife went through a very awesome program at a Houston health care center, and she lost over 75 pounds. She’s kept it off this entire time, but we had to make changes. We made changes in the way we ate and how much we ate.

Going back on watch and wait

Since she was exercising, I started exercising. Being a Type A personality, a little bit OCD, walking around the block once or twice turned into 5Ks, turned into 10Ks, turned into half marathons, turned into a full marathon. It was pretty cool. My mindset was, “I have to do something to make sure that what I got is not squandered.” I did that, and I kept at it.

After a while, I noticed that the fatigue was creeping back in. I noticed that the “allergies” weren’t quite allergies, because there wasn’t any oak pollen in the air. There wasn’t any tree pollen going on. There wasn’t the typical Houston-area mold going on. It was my body going, “Hey, there’s a problem.”

‘Go enjoy all the stuff you need to do to smile. Everything in moderation, including moderation.’

Jeff’s Doctor

I had that appointment at Anderson, and they did the blood work. My doctor came in, and he had that look on his face. I knew what that look meant. My habit of always giving my doctor a bottle of red wine every time he gave me good news was coming to an end, because he was going to tell me that I was in relapse.

I was, and it was okay. I really wasn’t prepared for him to say, “And we’re back in watch and wait,” because that’s exactly what the program was. In my mind, watch and wait was a one-time thing. It wasn’t something that had the potential to be multiple [times].

I was like, “Wait, we’re doing watch and wait again?”

He said, “Your blood work’s not great, but your symptom load’s not horrible. So let’s wait. Let’s see how it progresses.”

Has it been hard to get back into that state of watch and wait?

It’s been easier this time than it was the first time, because I know what this means. I have a different doctor at Anderson because my doctor retired. He was entitled to retire. He’d been doing this for a long time. My new doctor had a wonderful way of explaining watch and wait in a way that I hadn’t heard of before.

He said, “Look. Think of it this way. At MD Anderson, our job is to keep you alive, period. The longer we keep you alive, the more time we have to develop more medicine, better medicine, less toxic medicine. I’ve got some really good stuff in my pocket right now that I can treat you with now, but you don’t really need it now. If we push this out another 6 months, year, 2 years or 3 years, just think of what we’re going to have in store for you.”

I’m good with that. I know what the combination would be if I were to need treatment right now. I also now know some of the candidates for what the treatment might be 6 months from now or a year from now.

Staying healthy while accepting limits

Can I go drop off my briefcase, head out the door and knock out a half marathon right now [while] speed walking? No, I’m going to have to work up to that.

I don’t have as much gas in the tank, but I still speed walk every dang morning. I still do my sit ups. I still even play around with dumbbells. For the love of all that’s holy — my daughters have me eating oatmeal and chia seeds with fruit in the morning. I’m putting in the effort. The oatmeal is not really that bad. It’s just weird. I’m putting in the effort, and I’m still enjoying everything that I do.

Yeah, I’m in watch and wait, but the oppression is not as heavy as it was, because I’ve got an understanding of what’s going on.

Living life with moderation

When I first started seeing the folks in Anderson, I felt the need to do this confessional thing.

“So, Doc, you need to understand, I do enjoy the occasional cigar. I smoke a briar pipe from time to time. Is that going to be a problem?”

“How often do you smoke, Jeff?”

“Couple of times a month.”

“Not worried about that.”

“All right, Doc, you need to understand, every night I have a whiskey or 2.”

“Really? What kind of whiskey do you drink?” I had to name it off. He said, “When was the last time you were drunk?”

“1992.”

He said, “I think we’re good.” I opened my mouth again, and he was like, “Stop. I’m not here to make you miserable. I am here to help you live a great life. So go enjoy the whiskey. Go enjoy the bowl of ice cream. Go enjoy all the stuff you need to do to smile. Everything in moderation, including moderation.”

Now, I’m a dozen-plus years into it. I’ll share a little secret with you: I still have that whiskey every night, except it’s a much higher quality whiskey. Because why not? Why not? If I have that whiskey and pretend to watch something on TV, and I have fallen asleep and gone off that cliff at 8:30 in the evening, I don’t care. I’m up at 4:30 in the morning anyway, getting my exercise in. I still got 8 hours of sleep in. Who cares when it happens? Watch and wait’s not fun, but it’s not as horrible as it was the first time around.

What is the biggest takeaway you want people to remember?

I think the most important message that I can deliver to anyone who’s newly diagnosed with CLL is, “Get the right specialist on your team,” because doing that will allow you to get in the mindset of enjoying your life. Being diagnosed with cancer is horrible. It sucks all the air out of the room.

We have learned so much in 12 years about treating CLL. I am not going to shy away from the fact that there are some people who are newly diagnosed with CLL that are not going to have good outcomes. That’s still something that we deal with. But the truth is that for the overwhelming majority of people who’ve been diagnosed with CLL, some of you may never need treatment. And those of you who do need treatment are probably going to have a fantastic response from it and have the opportunity to live a great life.

Since that’s going to happen, from a Type A personality, make a list. What’s all the stuff you want to do? What’s all the good stuff that you want to do? Put it down on paper and keep your promises to yourself. Go live a great life, because it absolutely is possible. The fact that all these medical professionals are now using the C-word (cure)? Cool for us.

Inspired by Jeff's story?

Share your story, too!

More CLL Stories

Lynn S., Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL)

Symptom: Elevated white blood cell count

Treatments: Chemotherapy, targeted therapy (BTK inhibitor)

Serena V., Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL)

Symptoms: Night sweats, extreme fatigue, severe leg cramps, ovarian cramps, appearance of knots on body, hormonal acne

Treatment: Surgery (lymphadenectomy)

Margie H., Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia

Symptoms: Large lymph node in her neck, fatigue as the disease progressed

Treatment: Targeted therapy

Nicole B., Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia

Symptoms: Extreme fatigue, night sweats, lumps on neck, rash, shortness of breath

Treatments: BCL-2 inhibitor, monoclonal antibody

One reply on “Jeff’s Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL) Story”

Are you still in wait and watch. How long have you had this. How old are you now? It has been 20 years since I was diagnosed. Still wait and watch. I have my appointment on Tuesday.