Emily’s Cytogenetically Normal Acute Myeloid Leukemia (CN-AML) Story with NPM1 & FLT3 Wild-Type Mutations

Interviewed by: Alexis Moberger

Edited by: Katrina Villareal

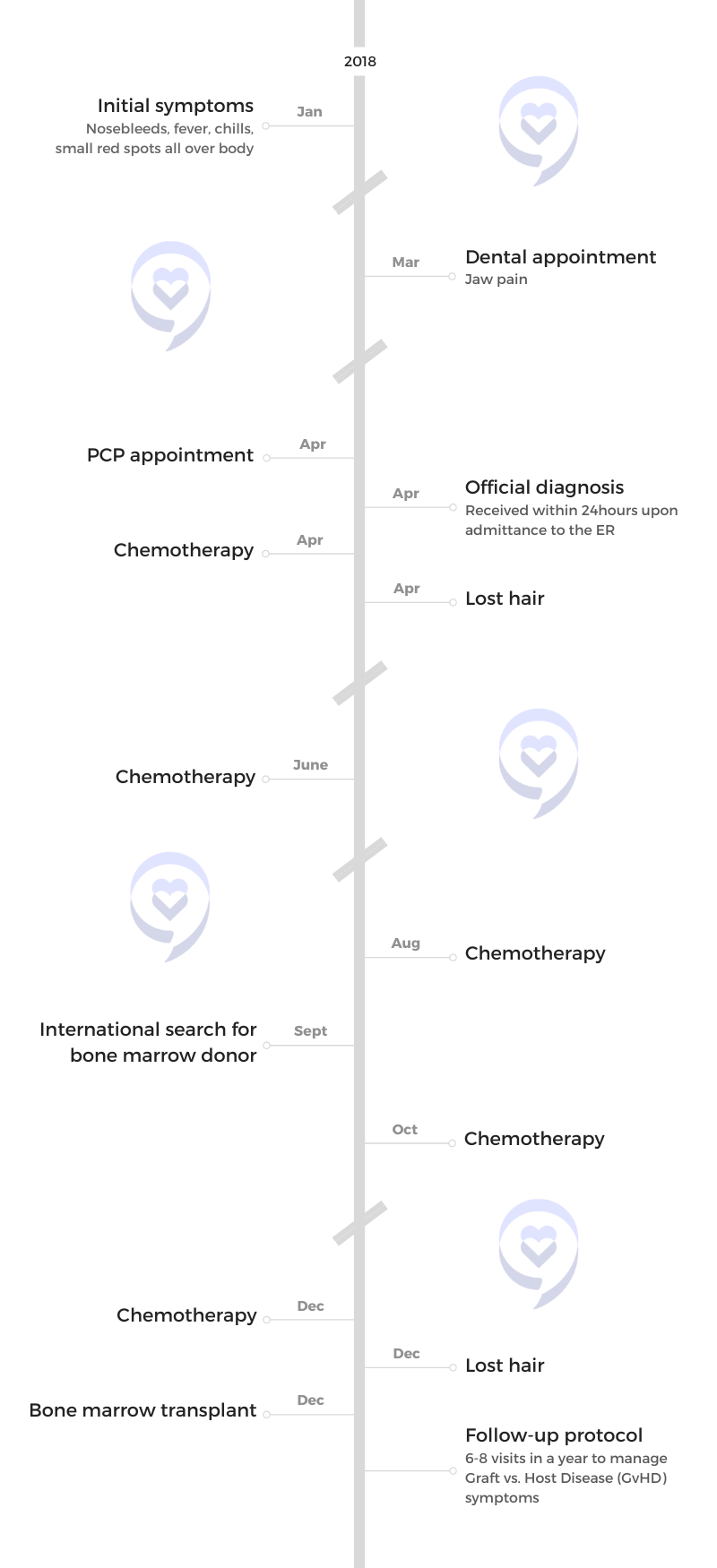

Emily shares her journey of being diagnosed with cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia (CN-AML) with NPM1 & FLT3 wild-type mutations at the age of 32.

She shares the challenges she faced during the diagnostic process while she was in a foreign country. She delves into the experiences of undergoing intensive chemotherapy, facing side effects, and eventually receiving a bone marrow transplant.

She discusses the difficulties in finding a suitable bone marrow donor, the emotional and physical toll of the transplant process, and the ongoing challenges post-transplant, including graft-versus-host disease (GvHD) and early-onset menopause.

Emily emphasizes the importance of self-advocacy, seeking multiple medical opinions, and finding ways to cope with the physical and emotional aspects of cancer treatment. She highlights the need for a holistic approach to healing, involving supportive relationships, lifestyle adjustments, and a proactive mindset. She also reflects on empowerment and resilience, emphasizing the individual’s role in navigating the complexities of cancer survivorship.

In addition to Emily’s narrative, The Patient Story offers a diverse collection of AML stories. These empowering stories provide real-life experiences, valuable insights, and perspectives on symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment options for cancer.

- Name: Emily T.

- Diagnosis:

- Cytogenetically Normal Acute Myeloid Leukemia (CN-AML)

- Mutations:

- NPM1

- FLT3 wild-type

- Initial Symptoms:

- Nosebleeds

- Fever

- Chills

- Small red spots all over the body

- Treatment:

- Chemotherapy

- Bone marrow transplant

This interview has been edited for clarity and length. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider to make informed treatment decisions.

The views and opinions expressed in this interview do not necessarily reflect those of The Patient Story.

Introduction

I was 32 when cancer happened. For most of my life, I’ve always been known as a fitness freak. I can’t even think of one hobby that doesn’t involve any sort of movement.

I’ve been in the health and fitness industry for almost 19 years, primarily coaching people in personal training and fitness, and, more interestingly, in pole dancing and aerial arts.

I was born in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, and moved to Tennessee at a young age. Since then, I have moved back to Asia and lived in Hong Kong, Dubai, and India. All of these places have taught me that it’s so easy to move to the next spot to see what’s next and say yes to everything because that’s life. You don’t say no to everything. You want to experience as much as you can.

There’s always a bit of a “too much” situation with most things and that eventually leads to burnout. At one point, I was living out of my suitcase for about two years for work and personal pursuits, wanting to say yes to every single project that came.

Now I live in a very quiet little town of Alicante, a bustling city in Spain.

I haven’t been able to eat proper food in three to four days. I only had soup and even then, I couldn’t keep it down.

Pre-diagnosis

Initial Symptoms

About three months before I planned to move to Spain for the first time, I started experiencing nosebleeds. I’ve always had nosebleeds throughout childhood but only when the temperature changes. I thought and was told that was normal. But this time, I had nosebleeds at the most random times, like in the middle of a squat or the minute I woke up.

Those were disturbing, but I chalked it up to traveling so much for work and not sleeping well. Typically in the past, when I didn’t sleep well, I tended to have jaw pain that would travel up the neck, which also included ringing in the ears. It becomes very hard to focus.

A few weeks before the diagnosis, I traveled for work from Australia to Hong Kong to pick up my stuff, to Dubai to pick up the rest of my stuff, and then eventually to Madrid, and then to Alicante. By the time I arrived in Alicante, I’d been on my third day of fever, which I thought was the travel and jetlag.

When I went to work the next day, I was told, “Hey, nice to see you! Are you okay?” People worried. “You don’t look as vibrant as you usually do. Are you okay?” My boss specifically said, “You don’t look okay. Are you sure you’re okay?” I brushed it off and said, “Nah, I’m good. Don’t worry. If I need to go to the hospital, I’ll let you know.”

The night before I went to the hospital, I noticed red dots all over my body, especially around my legs.

That night itself, I had an inclination that maybe something wasn’t okay. I haven’t been able to eat proper food in three to four days. I only had soup and even then, I couldn’t keep it down.

I was constantly shivering. I was shivering the whole way on the plane and the train ride. I was popping Advil almost every two hours. I noticed that every single time that I took Advil, it was becoming less and less effective. At the time, I didn’t know that I wasn’t supposed to be taking ibuprofen since it affects your blood count.

The night before I went to the hospital, I noticed red dots all over my body, especially around my legs. They weren’t itchy, but it looked like someone used a red pen and drew dots all over my body.

I went to a local clinic the next day and told the doctor my symptoms, but she didn’t say much. She gave me paracetamol in an IV and told me to go to the main hospital in the middle of the city. I didn’t think much of it because I thought that was protocol for a foreigner in Spain.

When I got to the main hospital, they immediately brought me a wheelchair and said I had to go to the emergency room. When I got there, no one told me anything. They kept jabbing me for test after test after test.

The team at the hospital in Alicante believed that I had leukemia.

Diagnosis

Getting the Official Diagnosis

I was in the ER with not much news. One doctor tried to explain in Spanish that they don’t typically do this because they were waiting for one of the blood results from a leukemia specialist hospital in Valencia. They’re waiting for that final confirmation. The team at the hospital in Alicante believed that I had leukemia.

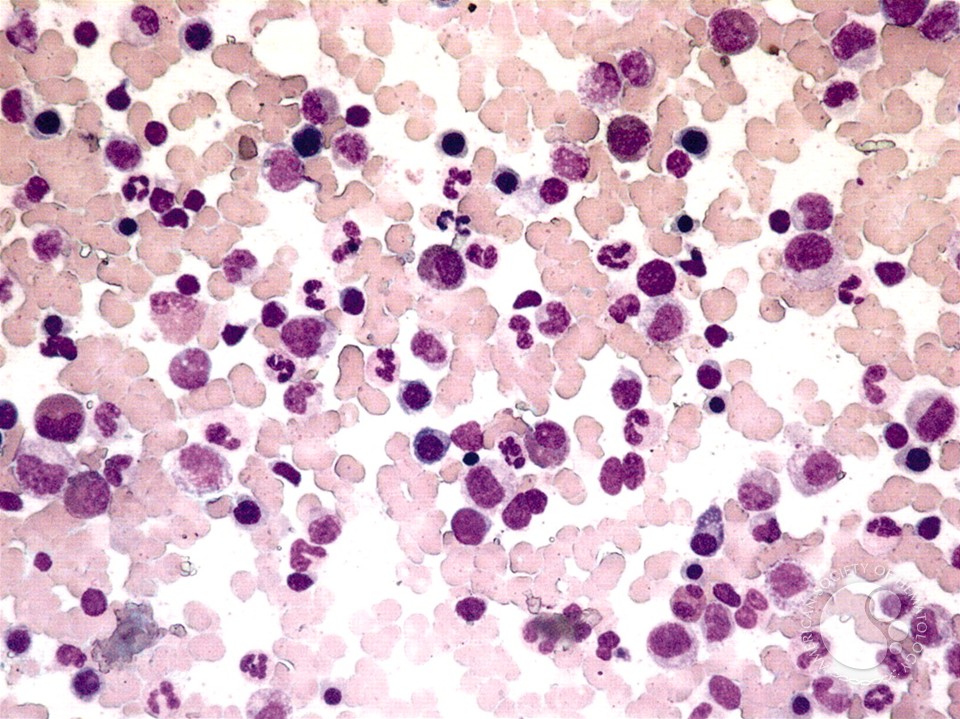

The official diagnosis was cytogenetically normal AML (CN-AML) with NPM1 and FLT3 wild-type mutations. This essentially puts me at intermediate risk. It’s not low-risk where you can get away with less-intensive chemo, but it’s not high-risk where a bone marrow transplant might be mandated almost immediately.

With intermediate risk, it gave me a little more time to understand what a bone marrow transplant was and how to go about it because I didn’t know anything about bone marrow transplants.

It also gave me time to do consolidation rounds with ample rest time in between. In total, I had five rounds of chemotherapy before the bone marrow transplant and each of them was intensive and each of them was done inpatient.

They didn’t give me a stage. I asked the doctors in Spain and Hong Kong. When I was in Hong Kong, I repeatedly asked the doctor, “Can you tell me more about what all this means and tell me the stage?” He’s a leukemia specialist as well as specializing in AML.

He said, “Right now, we don’t have the test for your specific biomarkers to give you a specific stage,” and that was in 2018. I don’t know if there is new testing available now that could give someone with intermediate risk where exactly they are in stages. But for me, that information was not available at the time.

Deep down, I knew something was very wrong. Even with the language barrier, the way the doctor presented the diagnosis felt sincere and sympathetic.

Reaction to the Diagnosis

I don’t know how that might have sounded if I hadn’t gotten first-hand information from the doctor himself. My friend had to translate and he didn’t realize what leukemia was at the time he was translating. Hearing the news brought to you in that sense was underwhelming but quite profound.

My brain went into logistical mode. I immediately whipped out my phone to Google, “What’s leukemia and how do you recover from it?” When I found out it was blood cancer, my survival instinct said to shut down Google. Then the next day, I texted people to tell them that I wouldn’t be showing up for whatever commitment I had committed to and that was it.

Processing the Diagnosis

Deep down, I knew something was very wrong. Even with the language barrier, the way the doctor presented the diagnosis felt sincere and sympathetic. I was in the ER the whole day. They didn’t do one test and told me they thought it was leukemia.

My dad asked, ‘Can we have some time to look for another treatment? Do we need to jump into chemotherapy so quickly?’ The doctor said, ‘She doesn’t have time.’

Bone Marrow Aspiration

The next big test was bone marrow aspiration. For leukemia and specifically for acute myeloid leukemia, they needed to do a bone marrow aspiration to see how much of it was in my bone marrow. That test tells you how serious the situation is as well.

There are two ways to get your bone marrow out: from the hip and the chest. They chose the chest area where you could see everything. I remember lying down, thinking, Just don’t look. I kept my eyes open for as long as I could and kept it shut the rest of the time. That was probably one of the scariest procedures I had to undergo.

At the time, I didn’t know there was another option. I didn’t know that you could ask for the hip version if you’re not comfortable with the procedure being so close to your vital organs. I don’t even understand why that happens, but I guess it makes sense to always have an alternative just in case the other area is not accessible.

I wish I could have asked for the hip version where I didn’t feel like there was such a compression. Even today, I find myself breathing tightly and that might have been an aftermath and the reflex when you have such a forceful extraction from the chest area.

They gave a local numbing agent, which helped, especially when the first needle went in. It helps you feel less of it. But I do remember feeling a lot of pressure, especially when they started pumping out the marrow. If you dare open your eyes, you will see someone looming over you with a very aggressive type of movement. You’re not going to feel the aggression, but if they have trouble extracting the marrow, there will be some force.

Treatment

Discussing the Treatment Plan

The very next morning, they came in and said, “It’s confirmed. This is what’s going on. Given your condition right now, we have to start chemotherapy right away.” At that time, I was still on painkillers so I don’t remember exactly what I said.

Before I could verbalize anything, my dad jumped in and asked, “Can we have some time to look for another treatment? Do we need to jump into chemotherapy so quickly?” He has a bit of experience with this because his mom went through breast cancer in her 70s. For two years, he saw how it wore her down.

But you have to appreciate how pragmatic Spanish doctors are. I remember this verbatim as well. The doctor said, “She doesn’t have time. She will die,” and that was it. Discussion over.

All things considered, it was good that I had chemotherapy and even better that my body responded to chemotherapy.

Chemotherapy

I asked him about my prognosis. “What’s the next step after this first round of induction chemotherapy?” Induction chemotherapy is “7 + 3,” which is the one I was given. You’re on two different types of chemo. One is on a drip for seven days 24/7 and the other drug is on a drip for three days 24/7 and that’s your induction round. What they hope to do with this round is to induce you into remission, but it’s not considered complete remission from the disease. It has to be above a certain marker to qualify for the next round of chemotherapy.

They gave me three rounds because of the conditions that they said, “Considering your age and that you’re in a healthy weight range, we believe that you have a high chance of recovering from these intensive chemotherapies.” Hence why I was inpatient because they increased the dose on everything so I think the prognosis was positive.

It would have been a different story if my dad had argued and said, “Nope, I don’t believe in chemotherapy. Let’s go with another form of treatment.” I also developed pneumonia while I was in the hospital for the first round.

All things considered, it was good that I had chemotherapy and even better that my body responded to chemotherapy.

The induction chemotherapy included cytarabine. It was one of the drugs that was consistent in the induction round, the consolidation round, and the last round in preparation for transplant.

Cyclophosphamide was the one that was introduced right before the transplant. That was one of the more toxic ones but also one of the stronger ones.

There was also daunorubicin hydrochloride.

Side Effects of Chemotherapy

My side effects varied. During the first round of treatment, the induction chemo, I thought that was going to be as bad as it goes. There was nausea, but what was more prominent was gut pain. I couldn’t eat. I was put on an IV drip for seven days because I couldn’t eat literally and they had to give me nutrients.

I had skin reactions and somehow, I developed an allergic reaction to platelet transfusion

My bowel movement was very uncontrolled for about 20 days. It wasn’t until two days before leaving the hospital that I felt the side effects were finally under control.

I was in the hospital for three weeks for that first round of chemotherapy. I lost my hair. I had a lot of fever as well. Every time the fever happened, it was also accompanied by bad coughing, which explained the pneumonia.

I was given morphine for the gut pain because it was so painful that I couldn’t even function. Even when I had people visiting me, it was hard to talk. I was also given fever medication, antifungal medication, and antiviral medication. They did one scan to see how things were going in terms of the gut because it was so painful.

Throughout the consolidation rounds, the side effects weren’t as bad. My platelets dropped. I had fevers, but they weren’t as intense.

The worst side effects I had were skin-related. I had skin reactions and somehow, I developed an allergic reaction to platelet transfusion, which is ironic because that’s something I needed throughout my treatment. To counter that, they had to give me an antihistamine right before a platelet transfusion to mitigate that reaction.

Managing the Side Effects

The chemo before the bone marrow transplant was the most intense. That was when I started to second-guess myself. But during the first round of chemotherapy, what helped me was a sense of acceptance: to sit there and trust that my family and my friends have my best interests at heart, in how they communicate with the doctors, with the medical team, and also asking questions on my behalf.

In the first round, that’s when you’re very dazed, especially when you just heard your diagnosis two days ago before you started chemotherapy. In that situation, open yourself up to someone that you can trust. It was the moment when I felt like I could surrender to whatever higher power there was as well as conventional medicine. That was when I felt my parasympathetic nervous system start to settle a little.

If I’m in fight or flight mode, I don’t think my body biologically would have the ability to handle the side effects. My sense of touch was very strong. My mom was there. She gave me hand and foot massages. She gave hugs. All of those are the type of medicine that people don’t value. I realized how much power we can open ourselves to if we take a step back.

The chemotherapy before my bone marrow transplant was the hardest. The pain was the most intense. The fevers were relentless.

The steps that I took throughout the consolidation round were very helpful. I used the hospital grounds as my exercise place. I was taking walks around the nurses’ station. With every step that you take moving forward, you can feel yourself taking ownership and taking an active role in your recovery. Even if it’s five minutes of walking, even if it’s two minutes of walking, it’s something. It’s a physical representation of you taking action for what you can’t control, but you can still try and it still counts.

I leaped into my hobby of martial arts by watching martial arts movies, martial arts tutorials, and TV shows. I don’t have a martial arts background, but I enjoyed Thai boxing and jiu-jitsu as an adult. I can see how it’s not about the physical strength, but the mental agility that you have to exercise when you have to make decisions in the ring or on the mat.

Those don’t apply to everybody, but there are still some things that we can take from them. We can practice resilience in everyday tasks, like when you’re taking pills that you don’t want to take, but you’re taking them because you know that it’s going to help you. In a way, that’s a tiny practice in resilience.

The perspective exercise is to also see every little thing as, “How can I see this differently? By seeing it differently, I can do something differently. By doing something differently, I might get a different result.”

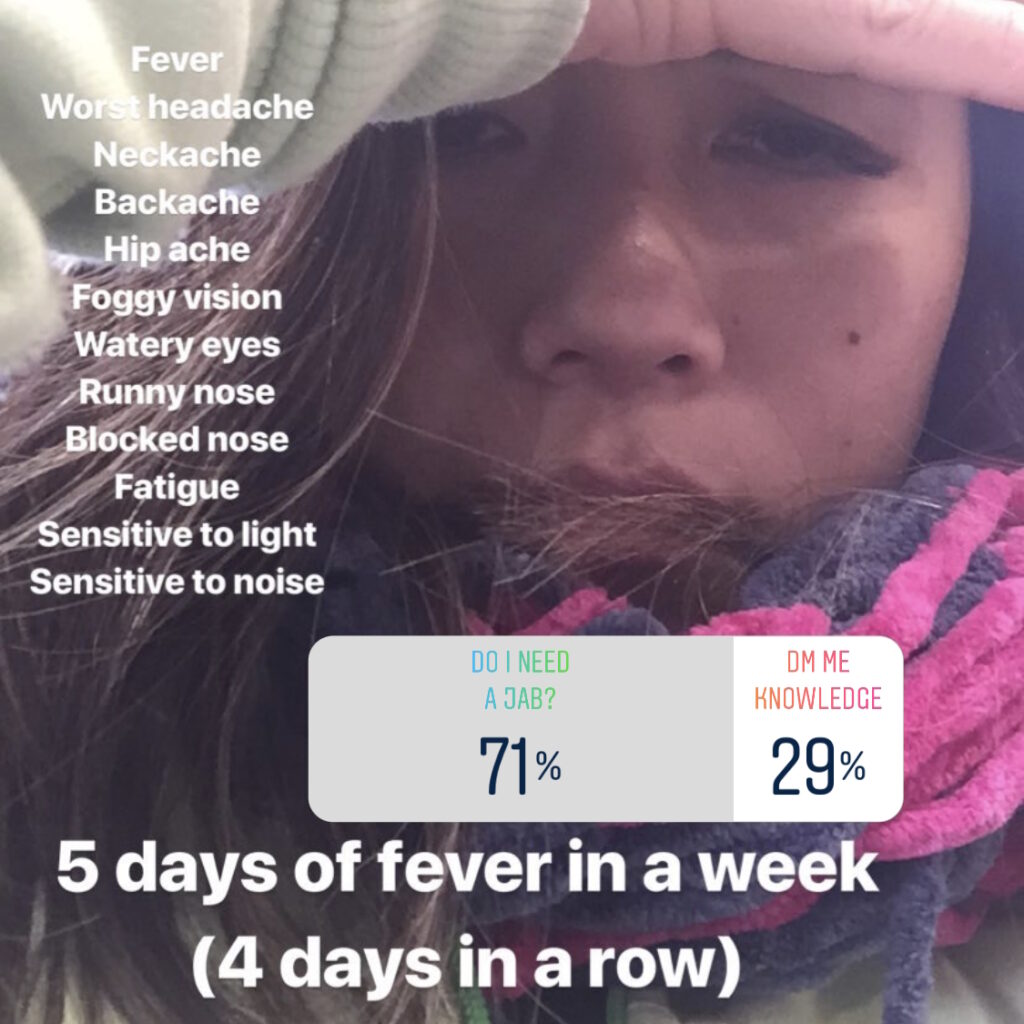

The chemotherapy before my bone marrow transplant was the hardest. The pain was the most intense. The fevers were relentless. I went into anaphylactic shock once during a platelet transfusion, but, luckily, I rang the call bell and everything was sorted.

I had a splitting headache and I got worried that it was a hemorrhage. Luckily, it wasn’t, but it was very important to articulate the sensation of how it occured. I timed it as well in terms of when it happened and how long it usually happened. This is important information to give to our medical team.

That’s what I mean by seeing things differently, being able to see everything that occurs. This is something that I can track. How can I build this case for my doctor to help me the best way they can?

I didn’t realize how difficult it was to get a donor. It’s complicated in the sense that your heritage matters.

Moving From Spain to Hong Kong

After the induction chemo in Spain, they gave me the green light to go back to Hong Kong. I told them, “I would love to continue here, but I don’t think the language barrier would serve me any good nor help you guys do a good job,” so I went back to Hong Kong.

I did all my consolidation rounds in Hong Kong as well as the bone marrow transplant. Luckily for me, Hong Kong had one of the most respected and prestigious transplant centers in Asia. It’s like everything was aligned.

I sought additional medical opinions outside of Hong Kong. I asked Australia, Canada, the UK, and Germany. The consensus was, “You are good where you are right now. Hong Kong has a very good system. They have a specialty specifically for bone marrow transplants there. They don’t even share that ward with anything else, specifically just for that. You are in a good place.” That was very comforting to know.

Bone Marrow Transplant

When they said that I needed a bone marrow transplant, I thought that it was going to be simple. I didn’t realize how difficult it was to get a donor. It’s complicated in the sense that your heritage matters.

The conversation of bone marrow donation is only very popular in first-world countries or mainly English-speaking countries so unless you have Caucasian genes, you have lesser chances of finding a bone marrow donor match all around the world.

I was contacted by Be The Match as well as the Gift of Life Marrow Registry to see how they can help… Because of their reach, you have a higher chance of finding a donor.

Finding a Bone Marrow Donor

When I took my information to compare with my brothers, none of them were a match. Your siblings have the highest chance of being a match. They opened it up to Hong Kong and no one was a match. It was only when they opened it up internationally that increased my chances of finding a donor.

I was contacted by Be The Match as well as the Gift of Life Marrow Registry to see how they can help. I appreciate that these organizations are in place. Because of their reach, you have a higher chance of finding a donor, perhaps through one of their bone marrow donor drives.

Additionally, being a local in your area will play a big difference. My friends in Malaysia did a bone marrow donor drive at the pole dancing studio. My friends in Hong Kong did a bone marrow donor drive through a deadlifting fundraiser.

When it comes to the bone marrow donor, I didn’t realize that I had to pay a deposit for a search. I thought that was covered and you don’t have to pay for it, but I guess every country is different. At the time, I had to put down about HK$ 60,000 as a deposit to get the search going as well as cover the initial stages of getting a donor.

Once they have your information, they will put it in their system to see if anyone in their registry is a match. If they find a match, the registry will contact the donor to see if they’re still willing to donate and if they’re able to donate. If they’re pregnant, develop a disease, or age, these factors disqualify them from being able to donate. There are a lot of procedures before they even tell you that you finally have a confirmed donor.

The donor registry in Hong Kong did all of it. They got the news that they found a donor. The donor lives in China. Luckily for me, I was in Hong Kong at the time. China had a rule that they weren’t donating bone marrow anywhere outside of their territories except for Macau and Hong Kong. If I stayed in Spain, I probably wouldn’t have had the chance to receive that donation.

I don’t know if they changed their rules yet, but if they haven’t, that’s what you need to know. If you are of Chinese heritage and you can’t find a donor anywhere else, you need to be in a place where you can receive a donor from one of the biggest Chinese populations in the world.

Everything went well. I received the marrow. I remember specifically it felt like something glittery was coursing through the veins of my body.

Getting the Bone Marrow Transplant

That was probably my longest stay in the isolation ward. To optimize your chances of survival, they do everything in their ability so you don’t get a second disease while you’re in isolation at your most vulnerable.

There was a slight anxiety when I asked the doctor, “When exactly is the donation going to be? When is the marrow going to be extracted? When are they going to be on the way here? How long will they be kept until it’s time to be in my body?”

He said, “They will extract a few days before you are meant to receive the marrow.” I did the calculation in my head. I would be on day four of very intensive chemo, in which you made me sign a waiver that I might die from the chemo. If the donor changes his mind or something happens on the way, I might not receive the stem cells. The Chinese doctors said, “We try not to think about that. Let’s not talk about that.”

But to be fair, these are very important things to know. I’m the type of patient who the more you tell me, the more calm and collected I can be. When I don’t have the probabilities, my overthinking brain takes over and that’s not good for any recovering patient. In this case, knowledge is powerful.

Everything went well. I received the marrow. I remember specifically it felt like something glittery was coursing through the veins of my body. It wasn’t scary. It felt like a blood transfusion and that’s what it looks like. It goes through your port. It’s not painful.

As a precaution, they injected me with antihistamines and steroids because it’s possible to have an allergic reaction to some degree.

The graft versus host disease (GvHD) signs for me appeared earlier than what’s seen because typically, you only see signs after the two-week mark.

Side Effects of Bone Marrow Transplant

After the transplant itself, it’s expected that you will have side effects. The question is to what degree and how many of those side effects will require hospitalization or not. Most of my acute side effects happened while I was still in the hospital so they were able to counter many things.

I had a massive skin reaction. According to the doctor, the graft versus host disease (GvHD) signs for me appeared earlier than what’s seen because typically, you only see signs after the two-week mark. They saw signs within less than 10 days and it started with my skin then fevers and then mouth pain and headaches.

The skin was probably one of the hardest aspects as well because it was itchy. I had hives everywhere, including my face. It can be hard to look at yourself and even receive visitors during that time. If you’re a caregiver or want to visit someone, it’s not a bad idea to check in and respect that there are times when a patient doesn’t want to see anyone.

They gave me steroid creams as much as they could, but it was up to me to apply them diligently, especially when the weather was cold or hot. I kept asking for stronger medication, but the doctor said, “I can’t give you anything stronger right now because I’m waiting for the worst side effects to happen before I give you the stronger medication.” They were holding out on me for my good.

The gut pain this time was more intense. I was timing them as well to give the doctor an idea of what the pain was like and how frequently they were happening. Every patient is different. Sometimes we have to remind the doctors of that as well.

One of the common GvHD signs is the lungs are affected in some way. For me, it was the smaller airways at the bottom of my lungs. They’re not functioning anymore. They kind of have a blockage. I’ll be lying down sleeping and then I’ll start coughing all of a sudden because I need to get more air in.

The intensive chemotherapy I endured launched me into early-onset menopause… In my case, it’s chemo-induced and GvHD-related.

The more chronic GvHD signs that I’ve been living with until today are ulcers around the mouth. I had to change the food that I eat in terms of texture so no more potato chips because they’re too crunchy and stab my mouth. No more spicy food. Thankfully, I’m not a girl who loves spice anyway. There are certain seasonings that if they’re acidic, then I might get a nasty reaction as well.

Those are minor lifestyle tweaks. I’m happy to survive. If you talk to my current doctor in the hospital in Valencia, he will say, “Your quality of life is currently being affected. You’re not eating the foods that you like. Your sex life is very likely also affected. You can’t exercise as much as you can because of your lungs.”

But for me, part of the healing journey is also learning how to stop gaslighting myself. When it comes to disease management and having a background in health and fitness, it’s very common to hear people gaslighting themselves. “It’s fine, I can tweak it,” “It’s fine, I can do that,” or, “It might be this, it might not be that.”

One of the glands in my eyes is not functioning as well as it can so it causes very dry eyes. If you don’t manage it through medicated eye drops, regular checkups, and other practices, it can lead to worse eyesight conditions and ocular health.

Early-Onset Menopause

Part of the GvHD signs also include vaginal dryness, causing the capillaries in the lining of the wall to thin so during intercourse, pain and bleeding can happen. The intensive chemotherapy I endured launched me into early-onset menopause so that also played a big part in vaginal dryness. In my case, it’s chemo-induced and GvHD-related so it’s helpful to understand the options when it comes to hormone replacement therapy and not taking one doctor’s word for it.

Doctors in different regions are exposed to different types of studies and different types of statistics. In Hong Kong, when he found out that I had breast cancer in the family, he said, “Let’s not do hormone replacement therapy. Let’s wait it out. Even though you’re menopause right now, wait it out.”

But in Spain, when I went to a gynecologist, he said, “I would have put you on hormone replacement therapy seven years ago when your period stopped.” I took one doctor’s word for it. It’s always good to have a second or even a third opinion, preferably from different regions.

In the first two years after the transplant, I was not in the mindset for physical intimacy. It had a big impact on my relationship.

Follow-up Protocol

Before the transplant, they did a bone marrow aspiration to see where things were. Right before I was cleared to leave the hospital, they did another bone marrow aspiration to see where things were. But after that, based on my blood work, the doctor didn’t see a need for any more bone marrow aspirations or biopsy. The blood work was a roller coaster, but not to the point where there’s a red flag so that’s a plus.

The other scans that they did were around the lung area. I do a pulmonary function test every six months. That gives the doctor an idea to see if the GvHD is being controlled or advancing.

I’m in my fifth year after the transplant. I’m still here. Regular checkups are not at a fixed interval. It’s whenever the medical system can give me an appointment, which is around every 3 to 6 months.

The first 100 days after the transplant, is when they monitor the closest. I had to go to the hospital once a week then once every two weeks, once every three weeks, once every four weeks, and then it was stretched out from there.

In my case, I still had to go in to get medication intravenously. The doctor said, “You need to live with someone. You can’t live by yourself right now. If you pass out, if anything happens with your port, you need to be able to call for help.” That’s also important to recognize.

Design your home in a way that’s going to be conducive to healing and recovery. That was the first time I started yoga. I have a bit of yoga experience now.

In the first two years after the transplant, I was not in the mindset for physical intimacy. It had a big impact on my relationship. We’re no longer together, but he didn’t stop showing up as a supportive partner so props and kudos to him. He didn’t leave me in that sense.

I had to go through a stage where I had to learn what it meant. I don’t know if it was their training or culture, but whenever I asked questions about our sexual health, I wasn’t given a very open response. It was only in Spain that I had a doctor who initiated that question. “Tell me about your sex life. How are you doing right now? How is your sex? How is your health?” That prompted me to share.

As cancer patients, we have this ideal image of ringing the bell and being cancer-free. That’s our finish line, that’s the glory, but it’s not the case for everyone.

Words of Advice

What I learned in this journey is that you can go to all the specialists, experts, and trainers as much as you want. Go to a therapist, go to a counselor, find a coach, whatever it is. It comes down to you. Extrapolate the feedback that you get and come to your own conclusion on how healing will be for you. It doesn’t come down to a doctor telling you, “You are now cancer-free.”

My doctor said that he could not give me those words because there were no tests that could give me that guarantee. “I can tell you that you’re responding very well, but I can’t tell you that you’re cancer-free.”

Hearing that made me realize that as cancer patients, we have this ideal image of ringing the bell and being cancer-free. That’s our finish line, that’s the glory, but it’s not the case for everyone. It wouldn’t be fair to impose that on everyone.

You can take power back by deciding what you choose to do. If you want to see a therapist, see one. I saw three. If you want to talk to coaches, find one. I have plenty of coaches even until today. It doesn’t make you a weaker person. It doesn’t make you a weaker personality. It actually makes you brave.

Inspired by Emily's story?

Share your story, too!

More AML Stories

Shelley G., Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) with NPM1 Mutation

Symptoms: Fatigue, rapid heartbeat, shortness of breath, low blood counts

Treatments: Chemotherapy, clinical trial, stem cell transplant

Joseph A., Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML)

Symptoms: Suspicious leg fatigue while cycling, chest pains due to blood clot in lung

Treatments: Chemotherapy, clinical trial (targeted therapy, menin inhibitor), stem cell transplant

Mackenzie P., Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML)

Symptoms: Shortness of breath, passing out, getting sick easily, bleeding and bruising quickly

Treatments: Chemotherapy (induction and maintenance chemotherapy), stem cell transplant, clinical trials

Grace M., Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML)

Symptom: Headache that persisted for 1 week

Treatments: Chemotherapy, stem cell transplant