Christine’s Breast Cancer Story

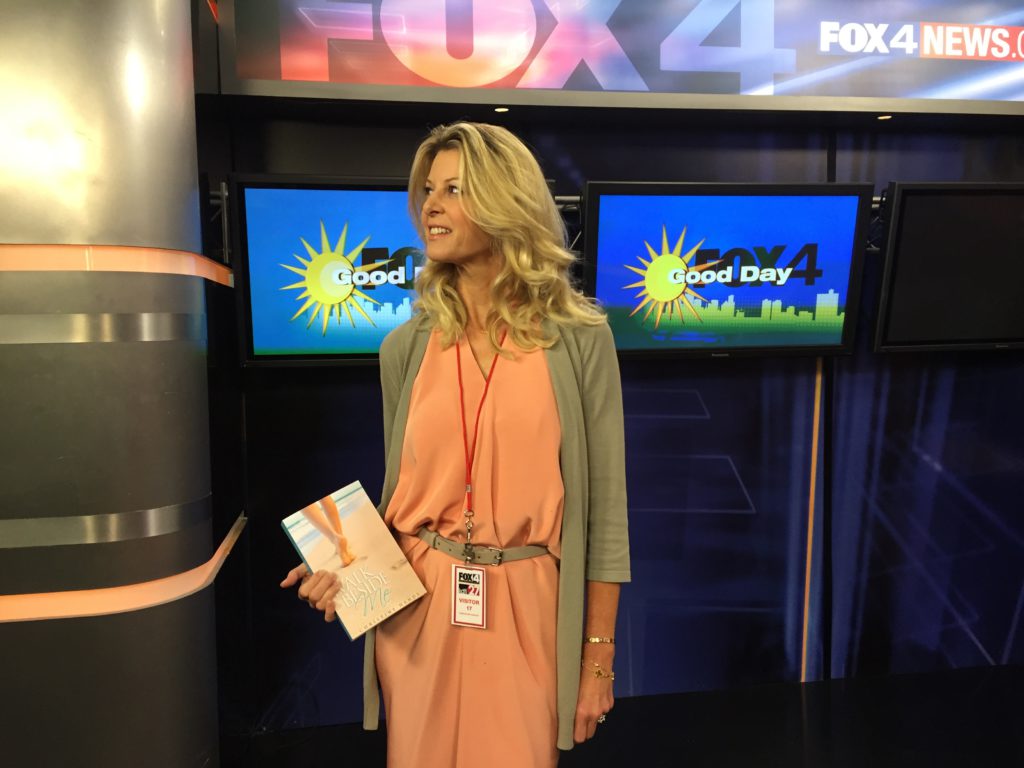

Christine Handy is a model, mother of two, and self-proclaimed Cancer Disruptor. Her life was forever changed when she was diagnosed with breast cancer at only 41 years old.

Christine used the experience to give back to the community. She is on the board of Ebeauty, a charitable wig exchange program for women who can’t afford wigs during treatment. She is also on the boards of People of Purpose and the Break Free Foundation.

Christine shares her story of becoming a thriver, advice for other patients on a cancer journey, and getting back into modeling for Victoria’s Secret after a series of surgeries.

- Name: Christine Handy

- Diagnosis (DX):

- Breast Cancer

- Age at DX: 41

- 1st Symptoms:

- Lump on left breast

- Tests for DX:

- Biopsy

- Other Tests and Scans:

- PET scans

- EKGS

- Echocardiograms

- Mammograms

- Treatment:

- Chemotherapy

- 28 rounds

- Surgery

- Lumpectomy

- Lymph node removal

- Mastectomy

- Maintenance therapy

- Tamoxifen for 8 years

- Chemotherapy

This interview has been edited for clarity. This is not medical advice. Please consult your healthcare provider for treatment decisions.

About Christine

Introduction to Christine

Who am I? Well, my name is Christine Handy, and I am called the Cancer Disrupter for a lot of reasons. A lot of very good reasons. I do like to disrupt the beauty space as a whole. On a personal level, I have two beautiful sons, 24 and 21 years old, respectively.

I call myself a self-proclaimed athlete. I love sports, which is maybe why I chose to live in Miami because there’s a lot of outdoor activities I can participate in. I like to be on the sand, usually walking, and I like to play tennis and paddle sports and row and things like that.

I am a big believer in serving and altruism. In every capacity of my life, I get to do that, whether it’s the nonprofit work that I’m a part of or in the social media space. I do work as an influencer, writer, student of life, mentor to breast cancer patients and survivors, mentor to prisoners because I work in that space as well.

I have a lot of different jobs. I wear a lot of different hats, but everything that I do professionally is a direct result of my heart and what I want to contribute to the world.

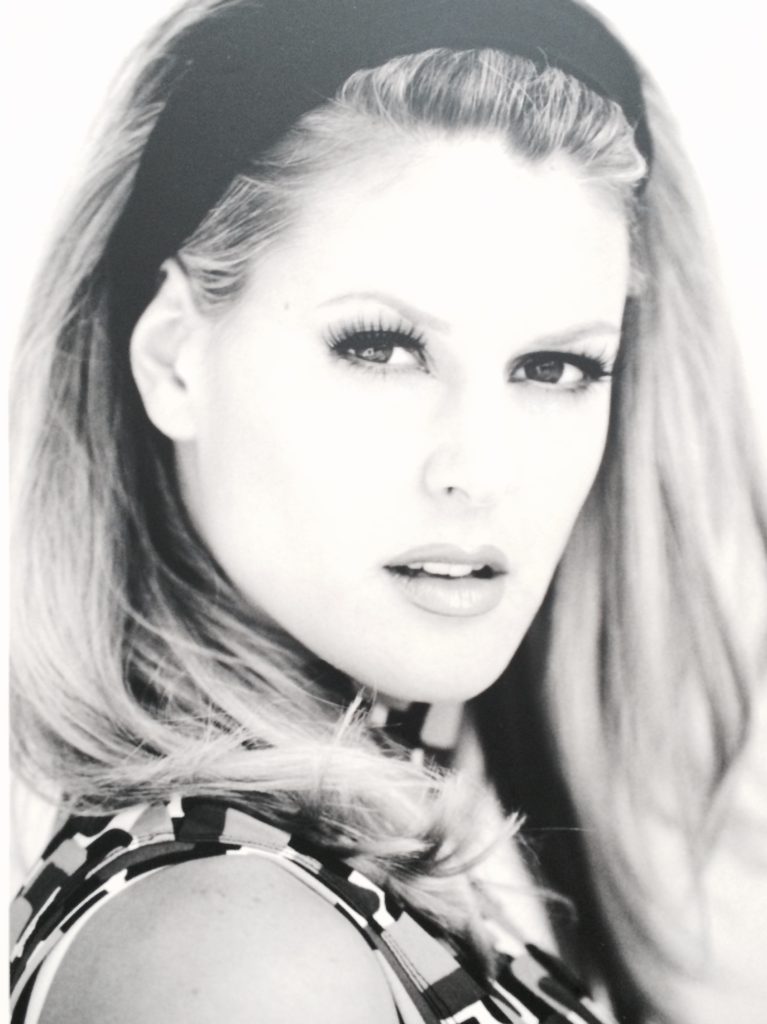

Career as a model

I was raised in Saint Louis, Missouri, and I started modeling there when I was 11 years old. I really had to kind of push my parents to allow me to get into that space. They weren’t the ones that wanted me in it.

When I turned 16 and I was able to drive myself to jobs, I was very independent. I missed a lot of school, but I was a very good student, so I would bring my backpack and my homework on photo shoots. While they were doing my hair and my makeup, I was studying.

I ended up doing well in the modeling space for many, many years. Ultimately, I stopped modeling when I was diagnosed with cancer. Of course, I didn’t think I would ever go back to it, but I ended up going back for a different reason.

I really loved the modeling space. Of course, it has different issues within the industry. Some of them permeated into my own life. I dealt with an eating disorder when I was quite young. But as a whole, modeling to me felt very safe because I’d been in that industry for so long.

Getting back into modeling

When I ultimately lost my chest in 2020, subsequent to my breast cancer diagnosis and implants and mastectomies, I ended up going back into the modeling space at 50 years old. I felt like there was a need to show that women without chests, their beauty is not lost.

You are still whole, and our self-esteem is what keeps us whole. Our faith is what keeps us whole. It’s not external beauty or external things like materials.

I took that opportunity in 2020 to say to my modeling agency and to my manager, “I’d like to go back into modeling, and this is how I want to do it.” It was a little bit difficult because they didn’t see or have the vision or the emotion that I did. It took me to really push myself and them to understand what I really wanted to do with modeling.

I went up to New York, and I went up to New York Fashion Week. I’d never been a runway model. I went up there with a vision to start walking in New York Fashion Week. Of course, now I was 50 years old and with a concave chest.

But I found my way into fashion shows and in front of designers and said, “My name is Christine Handy. I’m the beauty disruptor, the cancer disruptor. I’ve been a model for 40 years, and I’d like to walk in your show in February.”

Modeling with a concave chest

There’s women that need to see this. Women need to see somebody with a concave chest in the largest runway show in the world. That matters. Ultimately, several designers hired me, and I put on high heels for about a month prior to the shows because I needed to get my legs well versed in wearing heels again and also very high heels.

It was a very interesting process for me, and I showed it all over social media. People were rooting me on to completely figure out my walk. I did some YouTube tutorials and figured out how to do it. I ended up walking gracefully and beautifully in these shows, and it had a big impact.

Ultimately, I’ve walked in three seasons since then, including Miami Swim Week — which made a big splash, no pun intended — but it did make a big splash, because again, I was 50 years old and a concave chest walking in the largest swim show runway show in the world.

That took a lot of courage and bravery, but I felt like I had it inside of me and people, again, needed to see that. That’s a little bit of the history of my modeling career and why I continue to do it.

Christine’s Breast Cancer Journey

1st symptoms

I was 41, and like I said, I was a self-proclaimed athlete, a model, young enough, and didn’t have any family history. I felt kind of immune to getting cancer. Why would anybody like me get cancer?

I was allergic to sugar. You hear sugar promotes cancer and these types of things. I didn’t fit the box. It didn’t occur to me that I was going to have breast cancer.

I was in New York for a doctor’s appointment. I had just had a fused arm from an unfortunate incident with another medical issue, not cancer.

I was in the shower of a hotel, and my arm was hanging out of the shower because I have the huge cast on, and now my wrist was just rebuilt with cadaver bones and a cadaver Achilles tendon.

I’m literally 41 years old, trying to figure out how am I going to drive with a fused arm? How am I going to cook? How am I going to take care of my kids? I’m trying to deal with the gravity of that situation.

I’m in this hotel in New York. Previous to that cast, I had several for months. I was kind of used to having my arm out of the shower, but I wasn’t used to using soap. I would just pour liquid soap over my shoulder and let it run down my body and wash my body.

But in this particular hotel, they didn’t have any liquid soap, so I took the bar of soap. I washed my left breast, and I immediately felt a lump right beneath the surface of my breast. I thought, “There’s no way I have breast cancer.” Again, I have no symptoms. I have no family history. I have no reason to believe that.

Receiving the breast cancer diagnosis

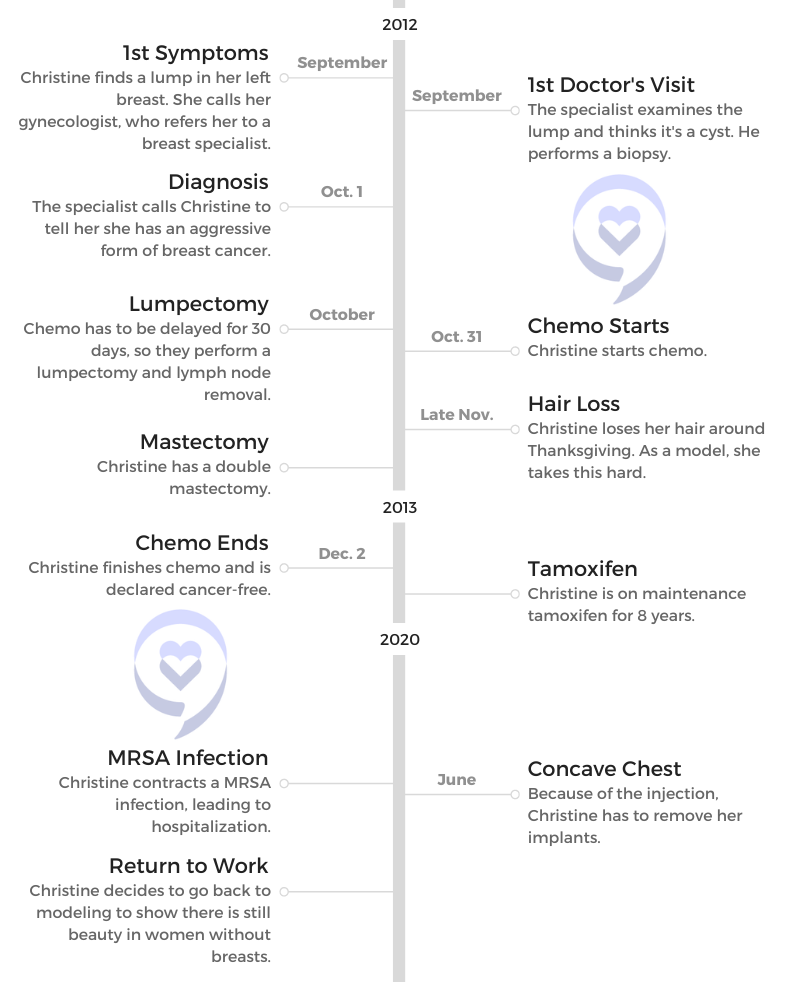

Ultimately, five days later, I was diagnosed with an aggressive form of breast cancer. The ironic part — well, there are so many ironic parts, which sometimes you have to think about the irony in things and think, “Maybe there’s purpose to this.”

For me, I was diagnosed on October 1st, which is the first day of breast cancer [month]. Instead of looking at it as now I’m going to be tortured for the whole month, seeing it all over the media and NFL and the pink socks and the pink this, I thought, “There must be a reason for me to be diagnosed on the 1st.”

The other thing is I wasn’t able to digest the fact that I just had a fused arm, and now I was facing chemotherapy, which had to be postponed for 30 days. If they had started the chemotherapy, the cadaver graft in my arm would have dissolved.

I thought, “This is some sick joke, right? I have cancer. Now I can’t even treat it.” That started a whole new level of duress into my psyche, into my emotional state.

»MORE: Patients share how they processed a cancer diagnosis

Hitting rock bottom

Ultimately, all of that pain and suffering and distress multiplied so greatly that I thought, “I am really at rock bottom here. I mean, I feel so deflated in life. I feel like, okay, my beauty is now going to be gone. My external value’s gone. Who will love me? I’m now handicapped in my right arm, and now I’m facing 28 rounds of chemo. I have no idea if I’m going to get through this.”

When I hit rock bottom, I had a choice, and the choice was you can either be a victim or you can be a vine. You can either show courage to yourself and your community and your family, or you can show despair. You can also show compassion to yourself, or you can show pity to yourself.

I went through this mental gymnastics of, like, do I really want to show pity? I kind of did in the beginning. Do I really want to show compassion to myself? I’m kind of mad. I had to really dig out of this hole with a lot of grace for myself, with a lot of courage.

I was facing a ginormous amount of distress and changes in my life and a lot of questions whether I was going to live or die. Again, I had young kids.

For the next 15 months of chemotherapy, I spent a lot of time doing a lot of introspective work and saying to myself, “If you do get out of this, if the outcome comes to your survival, then let’s not try to survive. Let’s try to thrive. And what does that mean? What does that look like?”

I have a voice, and I’m going to use it.

A transformation through words

I just decided in that moment I’m going to take notes. I’m going to keep a journal of the people that are helping me, the things that are going wrong, maybe the people that aren’t helping me, so I can remember all these moments and so I can write a book about it. Maybe that book can impact somebody.

That’s when I decided to write my book, and then I ended up publishing it. I was well and healthy, and it became successful. The other reason I wrote my book was because there wasn’t a book. There wasn’t a novel about a journey from start to finish and the good, the bad, and the ugly.

It wasn’t very appealing about me. My personality wasn’t so attractive before I was diagnosed with cancer. I was very self-serving, and I was very materialistic. I kind of filled myself up on what society wanted from me.

To go from that to living a life of serving and altruism, there’s quite a transformation, so I wanted to show that in my book. This is how you can do that.

Sharing your story of hope

My book is becoming a film, and one of the reasons why I’m so thrilled about that [is] not because it’s my story. Whether it’s a book or a movie, so often we see the protagonist or the main character die. Let’s say “Philadelphia,” the movie with Tom Hanks, or “Steel Magnolias.”

Take your pick. There’s a lot of illness movies out there that have been very successful movies, but typically the protagonist dies. When I was first approached about having my book made into a film, I said, “This will be different for the movie industry because I’m alive and I’m thriving. Wouldn’t that be a nice story to have?”

Of course, if it’s a film, it’s a bigger audience of hope. That’s what I’m trying to do. You always get criticized, of course, if you have a big platform. But people say to me, “Do you want a bigger platform?” Of course. I have such a beautiful story of hope; I have a light in the world. I have a voice, and I’m going to use it.

But I’m not just going to say, “This is the good part. This is a success. I don’t really care about the highlight reel. I care about the whole reel.” That’s what people are attracted to about my story. I will tell you the mess I was in, and I will tell you the vulnerability and the despair I felt.

I didn’t want to get stuck, and I didn’t want to get paralyzed in that. Ultimately, I didn’t run away, of course. Sometimes people don’t get out of that mess, and that’s why I think these types of stories are so powerful.

Physical impact of cancer

I was already depleted when I was diagnosed with cancer. I had had an infection in my arm for seven months that was untreated, and ultimately my arm was fused. Now I have cadaver bones that are trying to adhere to my body, and I’m trying to figure out how to live a life being handicapped.

From a physical standpoint, my body was depleted. My hair was already thinning, and that was from my arm issue. To go into chemotherapy depleted, and I was already underweight because of that.

Meeting the oncologist

At that point, I didn’t trust a lot of doctors because my arm doctor really had disappointed me. When I went to see my oncologist, I had already decided I’m not going to trust him. I just was like, “I’m not trusting doctors. They are not honest. Now my arm is fused. I trusted this guy. He was supposedly the best doctor, and now he’s let me down.”

I just had my guard up. The first time I saw my oncologist, I walked in the office, and he said, “Oh, you’re the girl with the arm.” He immediately diffused my fear, my anxiety. My walls already started to come down because he knew my story. He took the time to make a joke about it, and it was endearing. I immediately started to trust him.

He basically said to me in that appointment, “You’re not going to like me because you’re going to go through a lot of chemotherapy, and your body is already broken down.”

And he said, “And there are going to be moments where you and your friends and your family are going to think that I’m killing you or the chemo is killing you. It’s going to feel like that, but when you’re done, you’re going to be done because I don’t ever really want to see you again.”

If we take our hope away, we have nothing.

It was that kind of brash honesty, but also kindness, to say, “I don’t really want to see you around here anymore.” That really stuck with me. I thought, “Okay, I get it. I’m going to go through a lot of help. But if I can just survive this, I’m going to survive life. I’m going to be here to tell the story.”

Survivorship and Thrivership

Having hope in the darkest moments

That gave me hope. I think when people are giving a diagnosis and say, “Go get your affairs in order,” that takes away hope. When hope is lost, what do we have? The bags and the gifts and the accolades from society and the success — that makes no difference. But if we take our hope away, we have nothing.

He gave me hope, and so I stuck with that, even in the darkest moments. After my mastectomy and after 18 rounds of chemotherapy, I was able to get a mastectomy, and then I had more chemo, and then after my third revision of my mastectomy and after my faulty implant.

There were many, many surgeries where I thought, “Okay, this is the last one,” and then they kept going. Even though they kept going, I felt hope. I think that’s the biggest reason why I like to share my story, because it is a story of hope, and we can’t take hope away.

I’ve had about 23 non-elective surgeries in the past 11 years. I’ve had 28 rounds of chemo. I’ve had many complications from chemo. I lost three teeth because chemo gets in healthy cells as well. I have heart issues from chemotherapy. I have liver spots from chemotherapy.

Surviving is ultimately getting out of bed. You don’t have to do anything but just try to get out of bed, and that’s enough.

I see doctors regularly, not just my oncologist, for checkups. I see multiple doctors, and that can wear you down. I had an implant issue and ultimately a MRSA infection in my chest, so my implants had to be excavated.

Physical and emotional pain continuing

I have had no shortage of complications. But through all of the complications, I’ve said to myself, “How can we use this? How can I help people with this new complication, with this new story of pain?” Physical pain, emotional pain, and sometimes the emotional pain got to me, where I was like, “Is this ever going to end?”

I think that’s a subject that cancer survivors should talk about, because a lot of times when treatment is over or the perceived treatment is over, people go away and they move on with their lives, which is expected.

I’m not saying it’s wrong, but people need to know that there are people out there going, “Are you doing okay?” Checking on them, right? Just a text. Doesn’t have to cost money. It doesn’t have to cost you your resources or your time.

These are things that if caretakers hear the story, they go, “Oh, you know what? I’m going to text Susie today because I know she finished treatment a year ago, but I wonder how she’s doing.”

As survivors or patients, we can teach the world how to care for the ones that come after us. That’s our responsibility, so I take that very seriously.

Surviving and thriving

Survivorship certainly looks different for everybody. How it’s impacted them is so different. You can have the exact same disease. You can have lung cancer, you can have breast cancer, or you can have a brain tumor. Everybody’s tumor is going to be different, everybody’s emotional impact is different, and their physical impact is different.

One size does not fit all, which is why it’s important to have multiple stories and multiple points of view. When I talk about survivorship, it looks different for me. I don’t want to alienate people by saying, “This is how I’ve survived.”

I try to teach people to survive. It doesn’t necessarily fit other people. I try to look at it as thriving. I try to look it as I haven’t just survived. I don’t want to just be a survivor. I want to be a thriver.

What it means to be a thriver

For me, that looks like giving back to the community on all levels. If that costs me something, if that’d cost me some emotional distress by sharing my story, if that caused me some financial distress, that’s okay for me.

Because I know that when I was diagnosed, I felt like I was alone. I felt like I was alone in the diagnosis. I felt like I was alone in the journey. Not because I didn’t have friends and family there. I did. But again, if you don’t have contemporaries that have gone through it, you don’t really know.

For me, thriving is helping to give people hope because I’m living a story of hope, but also, again, talking about the pain and the complications and why it’s so important to have these conversations.

I also talked to breast cancer survivors who will say to me, “Today was the day of my diagnosis two years ago, and I can’t get out of bed.” Surviving is ultimately getting out of bed. You don’t have to do anything but just try to get out of bed, and that’s enough.

Teaching grace

I think one of the most important things that we collectively can do as survivors and as a community of people trying to help cancer patients is to try to teach grace. Take baby steps. Give yourself enough grace today to get through the day, even if it looks bad.

Give yourself enough grace today to forgive yourself if you’re angry, to forgive yourself if you’re mistrusting of doctors. That’s okay. When we give ourselves the grace and we show grace and we teach grace, that ultimately builds up our courage.

If I get mad at myself and say, “I shouldn’t have been rude to that nurse.” Okay, I’m having a bad day, and if I’m rude to the nurse, I can certainly go back and apologize to that nurse and say, “I’m sorry. This is my issue, not yours.” That’s grace. We all make mistakes like that, and that’s okay.

If you give yourself the grace, then you’re giving yourself the courage, and then you’re building your self-esteem, and then you’ve got your feet on the ground, and now you’re on level ground. Now you’re not staying in bed.

Survivorship looks different, but if we talk about it and we give each other grace, I think that’s a really good talking point, and that’s where we should start.

Advice for Patients and Caregivers

Letting go of the outcome

This is a tough one for people, and I truly believe this is the only way to survive. I think you have to get rid of the outcome.

When I was diagnosed with cancer, I asked a friend’s mother who had been diagnosed, “When do you stop being afraid?” She was 10 years out, and she said, “I’ll let you know.”

I thought, “Yikes, that’s going to be a long time. I don’t really want it to be that long. I want to get over this quicker.” I figured out a way to stop worrying about the outcome. I had no idea in chemotherapy whether I was going to live or die. When I was so fixated on, “What if I die? Who’s going to have the privilege of taking care of my kids?”

That’s just anger. That’s fear, and then anger. Fear translates into anger. When I said to myself, “Okay, enough of the anger. Enough of the fear. Don’t worry about it. Just have faith and just show courage today.”

Show courage for yourself, and then that may permeate to your children. That may permeate to your environment or in your community.

Not being afraid anymore

In the beginning, I was like, “I can’t let this go. I need to know if I’m going to live.” But when I practiced it day after day after day after day, I finally said, “Okay, it’s out of my hands. I cannot control whether I’m going to live or die. I cannot control whether I’m going to get cancer back. So why am I fixated on this fear?”

I had to figure that out inside, and once I figured it out, I let it go. I don’t ever think about getting it back. People ask me that all the time in interviews. They’re like, “How often are you afraid?” I’m not afraid. The reason is I let go of the outcome. I’m fixated on faith. My measure is not of this world, and that’s how I live my life.

Did you work on that internally or get help from someone?

That I figured out on my own. Although I was showing people courage, I was super mad inside. I thought, “Wow, this is a really double standard because I’m showing people that I’m hopeful, I’m nice to the nurses, and I’m nice to my friends when they show up.”

I was mad, and I was questioning my faith. I was questioning my life. Why was a model? Why do I feel sad that I lost my beauty? Why was that important to me? Why am I so fixated on the fear? Why am I so worried about getting through this and getting in the future?

I really had to come up with a plan for me. In the beginning, somebody said to me, “People are watching you. Be very careful how you show this journey.” And that really stuck with me. Those are two issues. The outcome is one issue, but also showing courage and showing compassion and showing grace for myself.

I got that from somebody who said to me in the very beginning, “People are watching.” I’m not talking about social media. I wasn’t even on social media back then. I’m talking about every single day, people are watching you.

They’re watching you, how you react. They’re watching you, how you live your life. It’s just human nature. People were watching me, how I was responding to the diagnosis, how I was responding to the trauma. Was I responding from faith? Was I responding out of fear?

I wanted to have a legacy, even if it was just in my own family, that I wanted to respond out of grace. I wanted to respond out of faith. If I could teach one person how you respond is all that really matters, then I was helping myself ultimately.

Self-advocacy as a patient

This is not a popular answer. Maybe that’s why I’m called the Cancer Disruptor. Medicine is a business. Let that soak in. It’s for profit. Growing up, I was taught that doctors were to be revered, doctors were to be respected regardless of what they said.

As a woman, there was even more pressure. I would see my dad talk to his doctors, and his doctors would respond differently to my father than they would do to my mother. I accepted that.

Well, when that happened to my arm, it became unacceptable. But here is the problem. It was inside of me. I didn’t have a very high self-esteem. My self-esteem had gotten chipped away for years in my life, in my profession.

When I was diagnosed with cancer, part of my panic was I have nothing to offer the world because I’m losing my beauty, which is all that people care about. That was a self-esteem issue.

So often we expect the world to protect us. We have to protect ourselves. It’s our job. That’s my job.

Needing self-esteem to be a self-advocate

Going back to the medical field, in order to be an advocate for yourself, you have to have a strong self-esteem. I didn’t have a strong self-esteem, so I wasn’t advocating for myself. You walk into these appointments, and you’re diagnosed with cancer, so you’re totally vulnerable.

It’s for profit, and you know that chemo is expensive. You have to say to yourself, “I have to ask hard questions.” I would absolutely tell people to bring somebody with you because half the time you don’t remember what they say because it’s so much. It’s so overwhelming. And take notes.

All we can do is today. We can’t do tomorrow. We can’t do next year.

Here’s the other problem. A lot of doctors are on a time [crunch]. You got 5 minutes. You can sense that. They’re not going to tell you that, but you can sense that. You feel this pressure, like, “I better ask this really quickly, and I don’t want to ask too many questions because he may get annoyed with me.”

That all goes back to self-esteem. We should be able to sit in that office as long as we are getting the answers that we deserve. We’re the patient. That is definitely changing in our world, but it takes sad stories like my arm for that to change, for people like me to stand up and go, “No, this is unacceptable.”

»MORE: How to be a self-advocate as a patient

Believing in your worth

But I also have to take responsibility for myself and talk about the fact that I had a low self-esteem, talk about that I had to work on my self-esteem, and talk about how I did that, because that’s what people want to know.

How did you do that? Well, I took back my voice. I took back the power of the thoughts that I had. I don’t know what I used to call myself, but it wasn’t nice things.

I changed those tapes in my head, and I started to say to myself, “You’re worthy of love. You’re worthy of doctors. You’re worthy of time. You’re worthy of this attention. You’re worthy of asking your friends for help when you need that.”

If you don’t have a strong self-esteem, you won’t ask for that because you’ll be embarrassed or you’ll have an ego issue. What if they reject me? What if they say no? You’ve got to build your self-esteem in order to be an advocate for yourself.

That’s a daily process. I have a little picture of me in a couple of different corners of my house. I look at that little girl, and I say to her on a day-to-day basis, “I will protect you.” Because so often we expect the world to protect us. We have to protect ourselves. It’s our job. That’s my job.

Viewing cancer as a season of life

When I was diagnosed, I thought, “It was so overwhelming. This is going to go on forever.” It’s just so much. I’m always going to have this now. I’m never going to be who I was before.

I felt like I was changed forever. Looking back, it was a season of my life. If we can look at it as a season of your life, it looks very different. Maybe I wouldn’t have been so overwhelmed because I would have been like, “Okay, it’s a season. If I can get through this season, then there’s another season. Not all seasons are bad. There’s going to be a good season coming.”

In the beginning of COVID, people would ask me all the time, “How am I going to get through this?” I’d say, “Like I did in chemo. It was a season of my life, and now this is a different season. It has a beginning, a middle, and an end. When it’s over, there’s a different season.”

If you can just compartmentalize it like that, it’s less overwhelming. It’s less grandiose; it’s less big. All we can do is today. We can’t do tomorrow. We can’t do next year. Doing those types of things keeps us present and not afraid.

If you think about the magnitude of 28 rounds of chemo, and I’m on number one and focused on 28 — how am I going to get 28? All that does is promote anxiety and fear and a low self-esteem.

If I was going to number one, I’d say, “I gotta get through number one. I gotta get through today, and we’ll worry about next week’s next week.” That’s not easy to do, but if you keep reminding yourself this is a season, that will help you get there.

Help and Support

Importance of your support system

I also think it’s really important who you surround yourself with. I know people have heard that, but really take inventory, especially during cancer and diagnosis. If there are people that are just not a part of your team, it’s okay.

They maybe don’t know how to act. They maybe don’t understand the magnitude. It’s okay to let those people go. They may be in your life in a different season, but maybe not this one. When I gave my certain friends that grace to kind of let go, that softened my heart, and that helped me not judge them. It also helped me not compare.

I think we need to focus on collaboration and not comparison in general, and in particular when you’re going through a diagnosis. It’s not fair to expect people to just say the right things and to be there how you want them to be there without asking for it.

I think that goes back to, again, the grace and also the grace of other people just saying, okay, you may not be here in the season, but I need people who are just going to cheer me on.

Borrowing courage from your support system

I also think that goes back to self-esteem and courage. I think if you have a strong self-esteem, the courage will come. I’ll say one more thing about courage. It’s okay to borrow courage from other people.

When I was in the hospital [in] June of 2020, there was nobody allowed in the hospital other than COVID patients. There were no elective surgeries. So if you were in the hospital June of 2020, you were very sick.

I had an emergency surgery to excavate my breast cavity for the 8th, 9th, or 10th time. I had like 104-degree fever, and I had this MRSA infection. They were taking me into surgery, and this nurse put these papers in front of me. I kind of lifted my head, even though it was hard to lift my head because I was so ill, to write down my signature.

I looked at it, and it said “mastectomy sign.” And I looked at her, and I said, “I can’t be having a mastectomy. I’ve had mastectomies in 2012.” She goes, “Just for insurance reasons.”

Here’s the problem with that. That’s a label. I’m basically signing a label of me having a mastectomy, which it’s not true.

Anyway, that’s a side note. I’m being wheeled back, and I have no idea what the outcome is going to be. I have no idea that my whole chest is about to be excavated. They don’t know what’s going to happen inside. They don’t know how big the infection is.

I come out of surgery. The next morning, the doctors come in. They’re about to take off the dressings on my chest, and they say, “Do you want to look at it?” Of course, we all have masks on. Again, it’s June of 2020, right after COVID started.

I don’t really want to show them how afraid I was, and so I say to them, “I don’t want to see it until I’m with somebody that I love.” I didn’t want them to unveil what I was about to experience probably for the rest of my life without somebody’s courage that I could borrow.

I needed my mother’s courage. I needed my father’s courage. I needed my son’s courage. I didn’t have any courage right then. It was a very lonely and depleting stage of my life. When I talk about courage, I’m not saying that I always have the courage, even with a strong self-esteem. But what I’m saying is it’s okay to borrow from other people and even use that language.

Just say, “Hey, Mom, I need to borrow some courage right now because I have nothing left.” I think it’s so important when you go through trauma and duress to remember it’s not all just on you. There are people out there that will lend you their courage.

Asking for help

You’ve got to get rid of your pride and your ego in order to ask for help. So often, especially for women, we’re expected to do it all and maybe not complain while you’re doing it, but to just suck it up. You got this. Come on. You got this. This whole women empowerment thing.

Hey, listen, I got it. I’m pretty unstoppable. But I ask for help, too. My pride and my ego went away when I was diagnosed with cancer. I have a strong enough self-esteem to say, “I don’t got this on my own, and I need people to help me through it.” There’s a big difference.

How are you doing now?

I’m good. I do see my oncologist a couple of times a year. I’ve had PET scans and biopsies on different places. She keeps an eye on me. I was on tamoxifen for about eight years until it became an issue with my endometrium.

Currently, I’m not on anything. I’m good. I feel very lucky. I feel very privileged. I feel like my journey had a lot of ups and downs, but in general, I feel like I’ve lived a very lucky life.

Inspired by Christine's story?

Share your story, too!

More Breast Cancer Stories

Amelia L., IDC, Stage 1, ER/PR+, HER2-

Symptom: Lump found during self breast exam

Treatments: TC chemotherapy; lumpectomy, double mastectomy, reconstruction; Tamoxifen

Rachel Y., IDC, Stage 1B

Symptoms: None; caught by delayed mammogram

Treatments: Double mastectomy, neoadjuvant chemotherapy, hormone therapy Tamoxifen

Rach D., IDC, Stage 2, Triple Positive

Symptom: Lump in right breast

Treatments: Neoadjuvant chemotherapy, double mastectomy, targeted therapy, hormone therapy

Caitlin J., IDC, Stage 2B, ER/PR+

Symptom: Lump found on breast

Treatments: Lumpectomy, AC/T chemotherapy, radiation, hormone therapy (Lupron & Anastrozole)

Joy R., IDC, Stage 2, Triple Negative

Symptom: Lump in breast

Treatments: Chemotherapy, double mastectomy, hysterectomy

One reply on “Christine’s Breast Cancer Story”

Hi Christine, I just came across your movie premier via my daily Substack email. I had no idea you existed and I am part of the flat community myself. I can’t wait to read your book and see the film. I was diagnosed in 2021 and had a double mastectomy, chemo, rads, the works! I was going to get implants but the chest wall expanders were so awful I told my surgeon after chemo is over, you can take those out and sew me up nicely. I am DONE. I never looked back and feel more confident than ever! I completed a huge educational goal and now work as a registered dietitian. At 50 I basically started over. One of the rare gifts cancer gave me is a much needed shot of confidence to add to my already broad repertoire of determination and tenacity.

I am so happy to see your site and learn more about you. Much love from your fellow “flattie” here in NW Florida.