What Does an Oncology Nurse Do

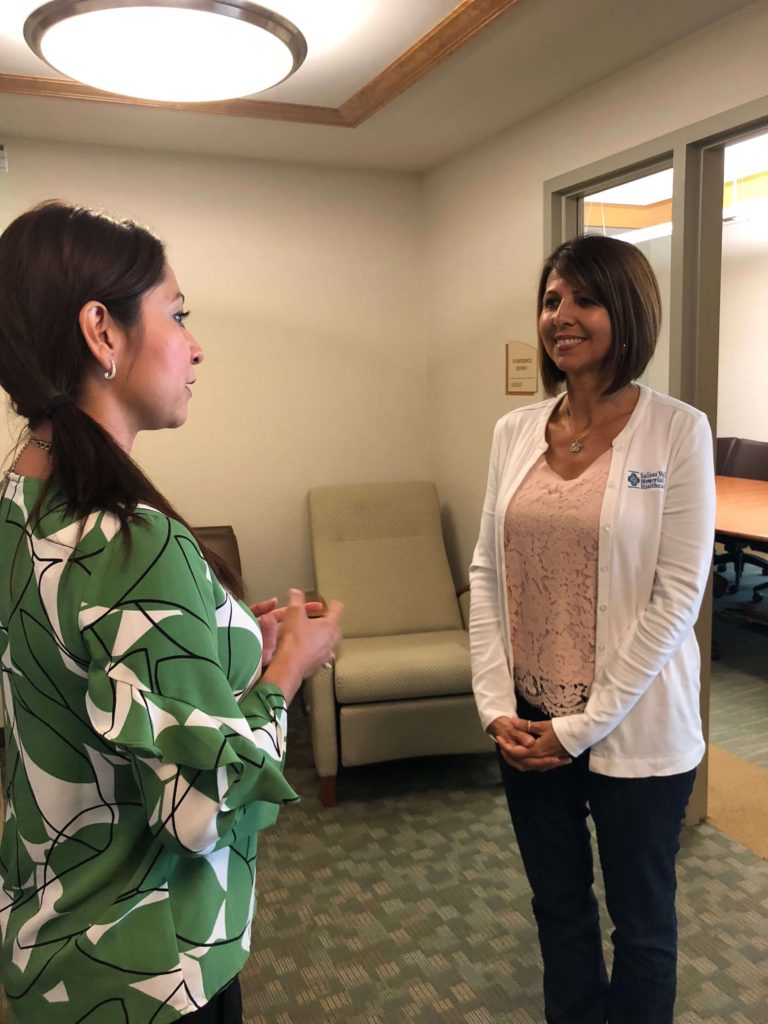

Bernadette Lucas-Burch, RN

Bernadette Lucas-Burch, RN is the warm face some people see when they or their loved one has just been diagnosed with cancer. So what does an oncology nurse do and how do we best navigate the healthcare system leveraging the help these nurses provide? Explore below.

My favorite part is what I learn from people. I truly come away sometimes just amazed. I’m a better person because of them. That’s my favorite part.

Bernadette Lucas-Burch, RN

- Name: Bernadette Lucas-Burch

- Experience: 35 years

- Registered nurse

- Nurse navigator

- Also clinical manager of Nancy Ausonio Mammography Center at SVMH

- Hospital: Salinas Valley Memorial Hospital

- ~260 beds

- Mid-range size hospital

- Your Job as a Nurse Navigator

- What is a nurse navigator

- First conversation with a patient

- What you avoid

- Following up

- Medium-sized hospital vs. smaller hospital

- Inpatient vs. outpatient experience

- Describe the medical team around you

- Is the social worker part of the initial conversation at diagnosis

- How different is the work between a nurse navigator and social worker

- What's your favorite part of the job

- Relationship with Patients

- How do you handle patients who go over appointment times

- Managing differences in styles with cancer patients and their caregivers

- What are some of the biggest quality of life issues that come up

- What questions should patients be asking

- Drawing from your personal experience

- How do you help patients deal with their emotions

- How do you handle patients who speak English as a second language

- What are the tools to help with ESL patients

- Bernadette's message to patients and caregivers

Your Job as a Nurse Navigator

What is a nurse navigator

A lot of cancer programs now have a navigation program built into them. The hope is to be there present at the day of diagnosis. After the diagnosis delivers that type of news, there’s just a vast array of how someone’s going to process that:

- What is that response?

- What’s the spouse, the caregiver, the friend, whoever’s accompanying them, how are they going to react to this news?

A navigator has the opportunity to be there, to be still, to listen, and to ensure they understand that there is someone there to help them. There’s a person to call. Mapping out those next steps.

Because after that news, in my experience and what I’ve seen is sometimes the shock is so intense for them that I don’t even know if they’re heard half the conversation.

So also having that navigator to follow up with a phone call the next day or in two days. Making sure the caregiver knows there’s a place to come, as well.

Cancer is not the disease of just the patient. It’s definitely a disease that impacts friends and families.

First conversation with a patient

First, we always let the patients ask or speak. Many times they don’t even know what to ask because this is a whole new territory for them.

The very first thing is you’re not alone. We’re here with you. You’re in great hands. You have a good team. Building trust. Making sure there is confidence in those that are caring for them because I believe healing is not just medicine.

Healing has other dynamics to it like trusting and being comfortable with where you are. I think that helps someone heal.

We try to establish that baseline for them. With all that shakiness that’s going on, let’s get some stability going on. Here’s a little bit we can offer you.

There’s a lot of support and lots of resources available but in that first meeting, I don’t think that’s the priority, I think many times people will want to know:

- Am I going to live?

- Can I go back to work?

- What’s life going to be like after that next hour I got a bomb dropped on me.

- How do we do that?

We do it one step at a time. One word at a time. One whatever that might be for them.

They might have children. There’s so many things going through their minds so it’s trying to reign that in for them and find that one focal point. How do we talk about what’s most important to them in that moment? Then just step by step getting them through that.

What you avoid

What I don’t want to do is put a time table. Yeah you think roughly an hour. Some people will take less, some people are very matter of fact and life goes on and then there’s those that emotionally it’s very difficult.

While you want to average an hour, sometimes you want to be open to not limit yourself if someone’s really struggling with acceptance or accepting, even hearing that.

That’s where the team comes in. You want to make sure that as you triage the needs, you’re pulling in your social worker, you’re getting the right resources based on what’s going on.

Following up

Once you do that, follow-up calls are extremely important. Let them digest all that information. We always provide them with a binder that has calendars. Their appointments are written down. We try to structure it in such a way that once they get home they can make sense of it.

The right then and there in the office is different. My philosophy has always been that my role is to ensure this patient knows how to live with their disease because I’m only here and there and gone. They have to go home with that. How do I successfully help them do that? No matter what disease it is, it’s theirs and we have to help them live with that.

Medium-sized hospital vs. smaller hospital

I worked in a community hospital. We were about a 50-bed hospital. While there’s good things about a smaller hospital because there’s familiarity, people you know in your community which I think can be very comforting, there’s also some difficulties navigating through the system for patients because there’s fragmentation.

There’s not a connection when a patient immediately gets diagnosed with a cancer. They may have to go to multiple appointments which can be very taxing versus a bigger organization where we are now, we can map things out.

We have the ability because we have all the specialities within our service lines to map that out for a patient so upon diagnosis our goal is always to have that path ready since we know what that patient needs the most.

We can also walk alongside them. That’s a significant difference that I see working with women from the community where I came from to the people here who have cancer, I see that they don’t have that.

I look at it is as a circle surrounding that patient. It’s multi-faceted so you need a team to address all areas of a patient’s life.

Inpatient vs. outpatient experience

Usually when you’re inpatient you’re a little bit probably sicker than you are when you are on the outpatient side. Chemotherapy, perhaps you’re dehydrated, perhaps there’s uncontrollable nausea and vomiting.

So perhaps you came through the emergency room with pain and that pain workup is what found your cancer. Being on the inpatient side is a little more, it has less let’s say, the nurses are doing their very best to take care of the patient but you’re on a schedule, there’s routines, there’s a lot of activity going on. So when you’re inpatient we know there’s business everywhere.

The navigator can assist at least reminding the patient that there will be ongoing support when they’re discharged. There’s disciplines set up 24-7 in the hospital so we never feel like the patient is without what they need. They’re definitely well-supported.

But there’s so much activity going on that I think patients don’t really need the navigator as much because they’re trying to focus on getting well from whatever episode might have brought them in. Neutropenia maybe.

Being respectful of their energy and what they need to do on the in-patient side, we usually introduce ourselves and especially follow up when they’re discharged home because we want to ensure that they know there’s ongoing support when they leave the hospital.

Some people’s chemotherapies are done as inpatients depending on the regimen and they need to be monitored. We know those patients aren’t going to benefit much from the work we do on the outside because they’re just not feeling as well.

They need to reserve their energy for what’s happening on the inpatient side.

We might be able to help and support families a little more during that time. That’s something we would focus on: inviting them over to the resource center.

Many times families may make their way to their cancer resource center when their loved one is in the hospital and it’s a good time for us to ensure that they’re taking good care of themselves during this difficult time.

Describe the medical team around you

You have your oncologist and all his physician teams. In our cancer resource center, we have nurse navigators, social worker who works with our oncology patient, dietitian, spiritual support and then there’s a multitude of different resources locally for the community for financial assistance.

That immediate group that would embrace somebody in the beginning I would think would be that core group. A lot of patients have dietary questions in the beginnings:

- Do I need to make changes immediately?

- What can I do to change my diet for this cancer diagnosis?

I think some things are more immediate than others and then you just slowly add as you need to.

Is the social worker part of the initial conversation at diagnosis

It’s usually a blended appointment, at least the first time we want to ensure that we’re both triaging the appropriate needs at the same time.

How different is the work between a nurse navigator and social worker

I think we dovetail on emotional support because I think we’re both trained well to do that.

Social workers really help a lot with the financial aspects of what someone is going to be facing or already facing. So people walk through the door with already-existing issues. The diagnosis certainly just adds to them. We’ve learned that.

It could be immediately needing housing, food, people are homeless – they get diagnosed so I think the social worker starts with those social aspects of finances, housing, transportation, huge barrier for our community here is transportation. How will these people get to and from where they live in South County or they live miles away.

Coping. Techniques on how to cope. Breathing techniques. Meditation. Mindfulness. So I can see immediately where that is a list that social workers help with immediately.

The nurse navigator is more – I like to look at us as we are the liaison between the doctors and the patients, so we have a lot of answers for some of the medical questions.

We can explain it a little more. We can accompany them to appointments to help them better understand what’s being said. Discuss medications. We can outline – talk about the diagnosis, possible treatments coming their way, what they can expect from the treatments.

We’re the medical side of it for the patient. Genetics – another big thing. We can talk genetics and should we be considering genetic testing?

Maybe explaining the patient visit again. Maybe the way the doctor said it. “I heard most of it but could you say it again?” Perhaps sometimes we can change how we present it that might make a better understanding. I like to think we have access through the backdoor so we can aways go do a doctor’s office and say this patient is struggling with this information or that information. Can you help me understand, too, so I can better go back and help them?

It’s really a partnership across the board, between the patient, the nurse, the doctor, everybody. So we help each other if I can help the patient understand, that’s going to prevent another visit or phone call to the doctor.

I think we try to help them make sense of it. I think the more they understand, the better for them.

Not everyone is interested in that. Some people are just not of that belief and they feel whatever the doctor says, I’ll just do. Then you have the other spectrum where they want to know everything and they’re well-educated.

I think to make them successful to live with their disease, whichever works, but the more they want to know we’re certainly willing to help them get that information.

What’s your favorite part of the job

My favorite part is what I learn from people. I truly come away sometimes just amazed. I’m a better person because of them. That’s my favorite part.

Relationship with Patients

How do you handle patients who go over appointment times

As a nurse navigator, you make appointments throughout your day. So you have to be mindful of the next patient certainly but I do think there is some flexibility within that.

I think being a nurse for as long as I have, medicine is not predictable. There is nothing about the human body that’s going to be predictable.

So if we try to box people into a calendar, it’s not going to work really well.

I think that if you at least acknowledge to the next patient, you can apologize, “I’m sorry there was a bit of a delay but it was necessary that I just kind of wrap this up.”

I think what you say to them in that is wow, if that was me, they would take that time. So that message is important because medicine doesn’t work on time, it just doesn’t.

We have to accept that because a calendar is not going to always, no matter what department you’re in, things are not going to fit in that time clock.

You have to be sensitive and realistic about those times where that patient just needs that extra 10 minutes and you could probably wrap it up, but you’ve allowed them a space to dump this out, regroup, and walk out hopefully a little more whole than they started.

Managing differences in styles with cancer patients and their caregivers

It’s very sensitive so this is about the patient.

Obviously that relationship came in the door the way it is so we’re probably not going to fix a lot of the dynamics that we see. We’re always open to having open dialogue and maybe role modeling. How they might better dialogue with each other. Maybe that can be helpful.

We want to care for the caregiver but primarily, we can’t give too much information outside the patient’s permission so that is very case by case dependent on what we can share.

I think exploring more about that. Why is there such a difference? Is there some denial going on? The caregivers – are they too overbearing with what they’re doing because that’s the way they’re coping.

And everybody does cope differently, and how do we meet in the middle somewhere? The last thing we want is frustration, people being at odds with one another, not agreeing.

Many times diet is a great topic to bring up in those cases. The patient may have one philosophy or doesn’t feel like eating especially during treatment time, and yet the families love language is no I have to stuff your face, why aren’t you just eating?

I think getting them to an understanding of right now that’s not a big important part of what they’re doing.

We know it’s important to her wellbeing or his wellbeing, but let’s meet in the middle somewhere. Let’s figure out how to do this so that you, above all, you want to enjoy that patient. You want this relationship to be somewhat of spending time together.

We never know what this disease can do and the last thing we want is someone to be arguing or having issues over topics that may not have as much meaning as we’re putting the emphasis on. So reminding them that the good news is you get to define this journey.

The patient gets to define the journey. We’re here to join it with them. What does that look like because primarily it should be them making the call. Then we just work together to get on that path with the patient.

What are some of the biggest quality of life issues that come up

One of the biggest things I like to address with young couples is the challenges they’ll face as a young couple. Intimacy. What does that look like?

Sexuality defined by the woman and the man. It’s my opportunity in the presence of the couple is to be able to help them start realizing that there might be some changes and that’s okay.

How do you redefine it for now? Maybe the next year won’t look the same. Intimacy can be defined in a lot of ways.

I stole this nugget from another nurse navigator but I would always challenge the partner to say, “So I challenge you to three hugs a day. If that’s all you can give, then that’s all you can give.”

And I’d be grateful if they even got one in. But I always thought it was nice to put something out, an example of something, like a gentle touch or hold is all she needs for that day. I think the couple needs to explore that together. What does that look like to stay connected? There’s this big barrier right now.

I always took advantage because I never knew if I’d see him again, so I always took advantage of that first sitting.

Typically in the beginning you get a lot of compliance and a lot of support. Sometimes people have to return to work and there’s a lot of dynamics, and I understand that. So it was precious to me to address those moments and those factors. We even had books.

One of our volunteer services purchased for our breast cancer patients a support partner handbook. I felt that was such a gem for these support partners to really get a better understanding of what those next steps were going to look like.

I said please don’t read the whole book. Please read it chapter by chapter just like this life is unfolding. I think that brought a lot of insight to understand how that other person may be facing the disease.

What questions should patients be asking

What does this disease mean to me? What changes can I anticipate? What are the next steps that I can anticipate? Statistics – sometimes people want to know all that. That’s not anything we get into, we always get them back to their physicians for that.

Just having some understanding of the disease to the point of how do I live with this? How do I support my loved ones? I always want to ensure patients don’t put too much stress on themselves and burden themselves.

“I’m strong, I can do this, I’m strong.” Then they tend to start suppressing their feelings because that word in itself is supposed to – warrant some way of suppression. Like:

“I’m not supposed to show my emotions.”

“I don’t want my family to know.”

“I’m just going to be very stoic and we’re going to get through this.”

That’s fine if that’s how they want to manage but I always want patients to know because you cry or because you break down, that is not a sign of weakness.

That has always been an important opener. Let’s learn about what you have. Let’s figure out what are those next steps. What does it mean to your life? How will this impact you?

And how are you going to cope with this? If you need to cry, by all means, cry. I think it takes more strength to be real with your emotions than it does to suppress them. So I always try to help them define – what are those words? Strong, weak. What does all that mean?”

Face the disease. Do what you can do each and every day. Just be who you can be. There should be no additional pressure on them. If they “fail,” in their mind,“fail” because I hear that from patients, have they really failed because a treatment didn’t work or this didn’t work? No. I think what they’ve done is their course has to go another direction but that’s not a failure, that’s the nature of where it goes.

Drawing from your personal experience

I have a personal experience when my mother-in-law living with lung cancer. Three years ago when she was diagnosed, that was what my husband did.

He said to his mother, “Mom just be strong.” The conversation ended. So later on I welcomed him to understand what just happened in that encounter.

“Well, what do you mean?”

I said, “Define strong. What would you like your mom to do to prove that she’s a strong woman you, to battle this lung cancer?”

“He’s like no, I just don’t want her to give up.”

“Well then say that to her. Did you realize when you said, ‘Mom just be strong,’ your dialogue stopped. Instead of reaching down inside of you, telling her what really was going on, what you feared, and letting her share her fears.”

Sometimes that big word ‘strong’ gets right in the way of a good heartfelt conversation that I think is more cathartic and healing. I think our society likes that word and it’s not necessarily a bad word but I prefer to make sure patients understand what it means to them. So they don’t miss out on those moments that might be a little painful to get out but are so necessary.

How do you help patients deal with their emotions

I’ve learned over the years and from other amazing role models that sometimes we as healthcare providers forget to give them permission. If we don’t ask the key questions, patients feel they don’t need to speak about it.

Going back to intimacy or sexuality- a woman will suffer through painful intercourse and not talk about it because no one’s asking about it. My doctor, he’s not asking. No one’s asking. The nurse didn’t ask. So why should I talk about it? I guess this is what I’m supposed to do.

We’re really good as human beings at suffering sometimes quietly because we think it’s normal.

I believe it’s us as healthcare providers that set the tone and we do that as nurse navigators in oncology right away. Just because no one asked doesn’t mean they’re not interested and it is your voice that matters.

So giving patients permission for whatever it is they need to talk about, it may not come from the health care provider, but that doesn’t mean we’re not interested.

Somehow I think we as healthcare providers, we get busy, it’s not the topic of the visit, so perhaps those don’t get addressed – but they matter.

I try to encourage patients overall to say we live in an amazing time. We don’t have to suffer. There are wonderful ways in which we can have some of these things taken care of. So that you can live somewhat of a more normal life. Intimacy is a huge, important part of that.

You’re allowed to ask. For some cultures it’s not an easy thing, ask is not an easy thing. You have to be culturally sensitive and word it in such a way depending on who you’re working with.

Sometimes we have to spin the conversations. Many times you will have patients who say, I don’t want the children, adult children, to know. It’s really helpful at times to say okay, I hear you, you’re a mom, you’re a dad, that’s your right, we’ll respect that.

But tell me if this table was turned. This is now your daughter or your son with a diagnosis. Do you want them to call you? Do you want them to leave you out? And most people when they see it from the other side say yeah I do.

Timing is theirs. They can decide when or how that conversation will be had, but I think sometimes giving alternate perspectives to things changes everything for people.

How do you handle patients who speak English as a second language

Thankfully because of technology we have language lines and iPads. They come in every language needed. I’m proud that our facility and our hospital as an organization is very culturally sensitive. We ensure our patients through an interpreter, whether that be a live interpreter or someone on our language line is able to be heard.

I think that that’s working with a large Hispanic population here, that’s just so vital. They’ll tend to just not talk or they’ll answer and nod and you think they’re understanding.

Because I have English as my first language, I learned that you also have to ask, ‘Did you understand what I just said?’

So critical. The nodding of the head and shaking doesn’t mean that they really understood you. Then they question whether or not they were heard.

To me that’s one of the biggest messages is: Do they feel heard? Do they feel like we understood them as well? There’s cultural sensitivity that’s really important. There should be no reason that we don’t have [the resources].

Even for deaf and mute, we have interpreters as well for them. We can accommodate all walks of life. I’m really proud of that. I think that’s so, so important.

What are the tools to help with ESL patients

Our iPad services are a touch of a button and a person is immediately on the screen. It does take extra time because you’re speaking your language and it’s this back and forth, but it’s doable. It does a little extra time but it’s okay.

It’s an iPad with all the languages and it’s linked to the same thing a phone would be, the language line interpreters. You just determine what language you need and they are actually visible, so now you see a person on the iPad. You not only hear them but you see them versus the phone where it’s just all audible.

They’re translating the whole time. They’re like in the room with you, that’s how I look at it is. They’re right there, their face is there. Sometimes we have to turn the video part off because in some cultures if it’s a male interpreter that got on, they may not be comfortable so we always check in with our patients.

“Are you comfortable? If I turn the video off are you okay with a male voice being the interpreter?” If not, we start all over and try to get a female interpreter.

The last thing we want is someone to be uncomfortable talking about some very intimate and private details of their life.

Bernadette’s message to patients and caregivers

While I know this part of your life journey may have brought you some challenges you never thought you’d face, I want you to know that the road ahead of you may have some bumps, but you will learn some invaluable lessons.

I have heard time and time again from patients that the silver linings that come their way could have been brought to them in no other way or fashion. I believe that my hope for you is that you find every life lesson that you can from this.

May it all make sense when you get to that other side so that you can give back to those other humans that you will encounter. This is about humanity.

This is about man to man, woman to woman. How do we help and connect with one another to ensure that each one of us has a much better life.

What Is a Clinical Trial Really?

Clinical trials can be confusing to navigate, so The Patient Story partnered with the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society (LLS) to discuss what a clinical trial is, the phases of a clinical trial, and figuring out the logistics of paperwork, scans, and finances.

Julie McFadden, Hospice Nurse

Hospice nurse: For last 5 years, helps patients and families understand end of life options

Experience: 14 years

Focus: Introduction to hospice, education

Jennifer Hagerty, Cancer Clinic Nurse

Clinic nurse: works mostly outpatient

Experience: 12 years

Hospital size: Large teaching institution

Brianna Banachoski, Hem-Onc Nurse

Nurse: works 12-hour shifts on blood oncology floor

Experience: was a lymphoma patient, became a nurse in early 2019

Hospital size: mid-range

Bernadette Lucas-Burch, Nurse Navigator

Nurse Navigator: help cancer patients and caregivers at diagnosis through treatment.

Experience: 35+ years

Hospital size: Mid-range but largest in the region

2 replies on “What Does an Oncology Nurse Do”

hello there. i was wondering if there are any coachings. i am a patient, i am trying to look into more because i havent felt well in the past year. my health declined after having pneumonia. a friend suggested lyme. i ordered my own test for that. im not sure if i agree with the possibility of me having lyme, but it doesnt hurt to check. are there ways to join a community to help get answers even if its never going to be cancer?

i want questionnaire about nurse navigator knowlege