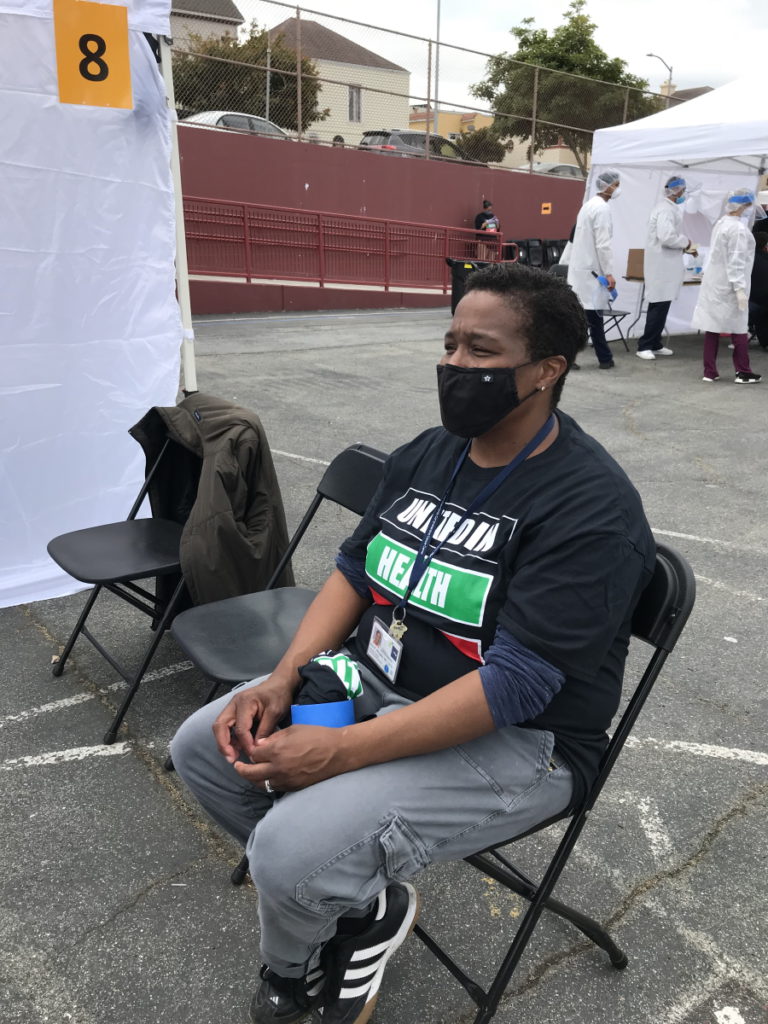

Kim Rhoads, MD, MS, MPH, Founder of Umoja Health

Kim Rhoads, MD, MS, MPH, is the founder of Umoja Health.

Dr. Rhoads is an associate professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at the UCSF School of Medicine. She is also an associate director at the Cancer Center in the area of community engagement and an affiliate of the Philip R. Lee Institute for Health Policy Studies at UCSF.

With the many hats she wears, the common thread is community engagement as a pathway to take action to get to health equity.

The interview has been edited only for clarity.

- What drew you to medicine?

- What personal experience really shaped you?

- What is health equity?

- What have you learned since then?

- Have things changed over time?

- Why do people go where they go?

- What are the solutions?

- How can we start the relationship on the right foot?

- How can small steps lead to big changes?

- How can we avoid otherization?

- How can we deal with the lack of trust?

- What are the next steps?

When it comes to cancer, the truth is different people need different approaches so equity refers to people getting what they need based on what they’re presenting with. That distinction is really important.

What drew you to medicine?

Stephanie Chuang, The Patient Story: What initially drew you to medicine and what drew you eventually to the area of cancer?

Kim Rhoads, MD, MS, MPH: Before we had the DEI language, I was in one of these pipeline programs in 1985 and 86. My mom happened to work at the School of Medicine at UC San Diego and she was in administration. They used to call her The Oracle. She was friends with the woman who started, I would argue, one of the first pipeline programs for underrepresented groups in medicine.

At 14, I worked in a lipid metabolism lab at UC San Diego for two summers in a row. I remember telling my mom, “Don’t get excited. I’m not going into medicine.” But the money was really good.

People in the lab took an interest in me and I liked science so it was fun for me to be in a laboratory. I already had a little bit of experience and the folks in my lab encouraged me to think about medical school. I was not thinking about that.

I majored in linguistics. I was not interested in being in the rat race. But as a junior in college and thinking about what a linguist does for a job, I decided to pursue the coursework to go to medical school.

I knew that it was a big commitment and that I needed to be making a conscious choice about going to medical school.

What personal experience really shaped you?

Stephanie, TPS: You were primed from a very young age, being in a lab at 14. You pursue medicine and, at some point, something personal happened that really shaped you.

Dr. Rhoads: I’d taken all the coursework [for medical school], but I decided to take a year off between college and medical school. Because I had worked in a lab, I was referred by my lab PI (principal investigator) to a lab in Washington, DC. I decided to move for a year [to] take some time and figure out, “Is this really what I want to do?” I wanted to take some time to make a decision [and] casually take the entrance exams.

I worked in an HIV lab at the time and my family is from Virginia, so I had a car. I would drive to Virginia on the weekends and spend time with my favorite cousin and my favorite aunt.

During that period, once I decided to apply for medical school, I was talking to them about interactions black people have with the healthcare system. My aunt was expressing that something was missing from her interactions with healthcare. I remember distinctly, she said, “I just want to be able to go to a clinic where when you walk in, people know your name.” But what I realized is she was asking for community. She wanted to feel like she was part of something, not like she was going into a situation where she would be judged for the choices she had made or how she lived her life.

I don’t want to be on a treadmill and then get to the end and find out that this isn’t what I really want.

What I didn’t know at the time was she had breast cancer. Nobody in the family knew. By my second year in medical school, the cancer had become so advanced she was not even offered surgery. She was treated with chemotherapy and died in the hospital. All contrary to having [a] choice, being supported, [and] feeling that warmth people need in a vulnerable time.

Because I’m [a] first-generation college graduate and [the] first doctor in my family, I thought, “Let me make a phone call. Maybe I could translate,” because I know that medicalese is being spoken and that people are probably not understanding what’s going on. When I called the hospital in Virginia, I was given a little bit of information. I asked if there was a specialist involved and was told, “General surgeons take care of breast cancer and we’re not operating anyway because the tumor is too large.” A lot of dismissive interaction.

By the end of the conversation, the person on the other end of the phone said, “Are you a nurse?” Because clearly, I had enough medicalese to get by as a second-year medical student. I said, “No, I’m a medical student,” and they hung up on me. That really stuck with me. This is not how it’s supposed to go, especially in that vulnerable time. That set me on a course of my original pathway in research, understanding the experiences of black women facing breast cancer and [their] relationship with surgeons.

What is that relationship like? Is it kind and caring? Did you feel taken care of and that somebody was looking after you? I remember one of the questions was, “Did your doctor make a U-turn at the foot of the bed?” It got me thinking about the fact that she never got radiation, which she needed based on the description of the tumor. That’s when I started to look into and think about it.

Many years into my surgical residency, comparing the different settings I had trained in — a Kaiser, a private institution, the academic center, the safety net hospital, the Veterans Administration — and seeing all kinds of different care provided for the same problem and making me wonder: Does this have anything to do with the difference in resources that are available? Going back to my aunt and asking the question: Was there radiation available at that hospital? As it turns out, there wasn’t so that’s why she wasn’t offered radiation. That started to form how I think about disparities because my suspicion was that you get the kind of care you get based on the institution that you select. And that brings us back to our question of inequities. Are people able to get what they need based on where they choose to get their care or where they’re forced to get their care based on their circumstances?

What is health equity?

Stephanie, TPS: What does health equity mean, Dr. Rhoads? We hear this now constantly. We hear about DEI in healthcare. What does that actually mean on a human level?

Dr. Rhoads: Health equity refers to everybody getting what they need. I think we started [with] liberation movements with the language of equality. But when it comes to cancer, the truth is different people need different approaches so equity refers to people getting what they need based on what they’re presenting with. That distinction is really important.

The word is now being overused. It is now being substituted for disparities. When we put the word inequity on top of disparities, what people are trying to refer to is the fact that these are addressable because if something is inequitable, it means it can be shifted towards equity. But by putting it over and covering over disparities, what we are effectively doing is trying to erase a state of being that exists as a result of inequity. It is the final common pathway of inequity. You end up with disparities. As long as we have inequities, we’re going to have disparities. But what we want to stay tuned for is the elimination of disparities by intervening to promote equity.

Stephanie, TPS: At the end of the day, words really matter and sometimes, it’s not really clear how powerful they are.

As long as we have inequities, we’re going to have disparities. What we want to stay tuned for is the elimination of disparities by intervening to promote equity.

What have you learned since then?

Stephanie, TPS: You were very conscious of this from the very beginning, even before you officially started seeing patients and becoming a surgeon. In the many years since then, what have you learned? Has it changed over time or are we still at the same place, depending on where you go for care?

Dr. Rhoads: Are we still there? Yes. The answer is yes. Most people don’t know because we don’t have a Consumer Report on what hospital you want to go to. There is website [for California] – CalHospitalCompare.org. You plug in your zip code, find the nearest hospitals, and look at their quality ratings. There were some efforts to try to promote better outcomes by ranking quality and letting providers know where the high quality is, letting the insurance companies know where is the high-quality care. There were several studies around 2005 [and] 2006 that came out showing that nobody was using those rankings. Referrals were being made based on personal networks.

My suspicion was that you get the kind of care you get based on the institution that you select… People don’t know that where you go determines what you get.

Whenever you talk about personal networks in [the] field of higher education, you know that those networks are going to be segregated. You can imagine how that can play out. Especially with the history in this country, for example, of black doctors only being allowed to train at certain institutions, only being allowed to practice in certain areas and in certain hospitals, [and] not being allowed to join professional societies with white physicians. That then is going to determine where your patients can go to get care.

California hospitals are still segregated by race [and] ethnicity but also by insurance status. That all came from policy, redlining, exclusion, and segregation in all of those layers — education and where you practice. That’s where patients are able to go.

Have things changed over time?

Stephanie, TPS: What you described, people might think, “Oh, that’s from before,” but what you’re saying is it’s very clearly still here.

Dr. Rhoads: It is. My aunt was treated in a safety net hospital and that’s the hospital that has to take you as a patient, regardless of your ability to pay. Your county has designated where those hospitals are. Those hospitals largely serve patients who have no insurance or Medi-Cal (when we’re talking California) [or] Medicaid (when you’re talking nationally).

If you rewind back to [the] ’64, ’65 civil rights era when Medicare and Medicaid legislation [was] being advanced at the federal level, the American Medical Association — which was very exclusive at the time, did not allow participants who were of color — [was] advocating against these policies. I don’t understand why, that doesn’t quite make sense to me. But the National Medical Association, a professional society created by black physicians out of exclusion, [was] heavily advocating for the passage of this legislation, in particular Medicaid, because they knew that those dollars were going to come to the hospitals where they were working and would have the opportunity for their patients to be covered by some kind of public insurance.

Now, what you’ve got across the country are hospitals that serve a disproportionate share of patients who have Medicaid or no insurance at all. What you’ll find is those tend to be your safety net hospitals so their revenues are not that high because they’re being paid by an insurer that doesn’t reimburse at a high rate. For example, Medicaid pays somewhere between $0.05 and $0.15 [per] dollar. If your total hospital bill is $10, you may get $1.50 back to the hospital to reinvest in their plants, property, and equipment.

Cancer care is expensive. A radiation machine costs money. A specialized CAT scanner costs money. If your revenues are low, those are not the investments you’re going to be making. That’s how you start to see a segregation of patients of color using high Medicaid hospitals for cancer care and then having to get whatever is available. That may not be the high-end PET scanner, may not be the CAT scanner that can slice the pancreas into thin enough slices that you can see a teeny little tiny tumor. If you need radiation and that hospital doesn’t have some kind of agreement with a place to provide radiation, you’re not getting radiation. That has a direct impact on outcomes.

When we looked back in about 2014 [and] 2015, we used publicly available data and asked which hospitals provide care to a high percentage of different racial and ethnic groups. We had what we called white-serving, Hispanic-serving, black-serving, [and] Asian-serving.

The one very notable thing is that white-serving hospitals do not overlap with black-serving hospitals and that they only overlap with Asian-serving hospitals. Hispanic- and black-serving hospitals are completely segregated. There are hospitals in California we can show you that have had zero black patients over a period of 10 years.

It really is segregated in a way that has not been amplified. We were looking at what was called minority-serving, so that was any non-white-serving hospitals. Those do not overlap with white-serving hospitals either. It is a pretty segregated system in California.

Across the country, minority-serving hospitals are black-serving hospitals. In California, minority-serving hospitals are Latino- or Hispanic-serving hospitals. Those are just some ways that we have looked at the data to understand the landscape of segregation that is still persistent in our healthcare system in a very liberal and very diverse state.

We used publicly available data and asked which hospitals provide care to a high percentage of different racial and ethnic groups… It really is segregated in a way that has not been amplified.

Why do people go where they go?

Stephanie, TPS: Sometimes, when we talk about these things, about race as a social construct and not just biology, I thought a lot of this is socioeconomic. If you live in a certain area and have limited means, you’re limited in terms of options. The most accessible hospital may be a safety net hospital. But you’re saying this is down racial lines. Can you talk about that? I know there’s another layer there. We talk about socioeconomic, but it’s very clear what you just described.

Dr. Rhoads: Socioeconomic factors — like income, education, [and] employment — track along racial lines as well. It’s hard to pull them apart.

We did publish a series of papers asking the question, “Why do people go where they go?” As you suggested, maybe you just live near the safety net hospital so that’s where you get your care.

We asked racial and ethnic minoritized communities [and] populations in California, “Would you use a National Cancer Institute-designated comprehensive cancer center?” That’s where the best outcomes, all the high-quality services, [and] all the specialists are. Then we also asked, “Would you use a high-volume hospital?” Because practice makes perfect, right? If you’re taking care of a lot of cancer, then your outcomes tend to be better. We’ve shown that that’s true.

We started off by asking, “What is the median travel distance that people will go in California to get colorectal cancer treatment?” We found that the median travel distance was five miles. Now there are all kinds of discussions that can be had about that. Five miles doesn’t seem like a lot. If you have a car, that’s short. If you’re on the bus, it might take longer. If you don’t have the access to either of those things, five miles is impossible.

We used that as a marker then we said, “What proportion of each racial and ethnic group lives within five miles of a National Cancer Institute comprehensive cancer center or a high-volume center?” It turns out that racial and ethnic minorities are the groups that live closest to these centers because they tend to be in non-rural areas in California. They live closer.

Then we said, “Of those who live within five miles, are you using them?” A lower percentage of racial and ethnic minorities who live within five miles of an NCI center or of a high-volume center were using them.

What’s going on here? Is it because some people are actually going where they can get better quality and going to a safety net hospital or high Medicaid hospital? Because that’s where the clustering of racial and ethnic minorities [is]. We asked, “Is this because of insurance?” The answer is no. Insurance did not move the needle. Insurance was not as statistically significant in its correlation. It did not explain this difference.

Then we asked, “Is it travel distance?” We counted everybody in because some people will be further than five miles out and travel distance did make a difference. So that was comforting because it makes sense. It has face validity.

But then we asked, “Is it possible that the neighborhood characteristics determine where you go?” We used education as the socioeconomic factor and it overrode travel distance. It neutralized the effect of travel distance. Travel distance did not matter. What mattered was [the] neighborhood education level. I know when I give this presentation on this series of papers, a lot of people will say, “I knew it.” They just don’t know better. But lots of people know better and still don’t pick the highest quality hospital, including insurers [and] referring providers.

The way I try to explain this is we looked at neighborhood-level education. It’s not the education of the individual; it’s the characteristics of the neighborhood. What we say is you are like your neighborhood. You’re like your neighbors in terms of your health behaviors because that is a marker of socioeconomics: What’s your neighborhood like? In your neighborhood, you’re in range with everybody else because you can afford to live there [and] you chose to live there. What we’re saying is neighborhoods develop patterns of where they get their care and that trumps quality and travel distance.

So that’s where my aunt went. If that’s where my grandma used to go, where my mom went, then that’s where we’re going because that’s our hospital. The problem is that if you peel back another social determinant — which is redlining and say, “Where are people allowed to live?” — then you become like your neighbors and you establish a relationship with the hospitals that serve that neighborhood. And those tend to be the safety net hospitals for racial and ethnic minorities.

Stephanie, TPS: Wow. You did ask all of the important questions. If not this, then what? While you were talking, I did think, “Oh, it must be the insurance.” And it’s not. The community events build a bridge of true understanding, not just, “You don’t know any better. You should be going here and this is why.” None of that.

What’s embedded in that history is a relationship and what that offers an opportunity to do is to have a different relationship.

What are the solutions?

Stephanie, TPS: What are the solutions?

Dr. Rhoads: What’s happened is a relationship has been developed, whether that relationship is for better or for worse. You might not be aware that you could get better outcomes somewhere else because that’s always where everybody’s gone. The crazy things that happen there that don’t make sense are perfectly acceptable because that’s the relationship and that’s where you’re talking about history.

What’s embedded in that history is a relationship and what that offers is an opportunity to have a different relationship. But what about now? And what about going forward into the future? That is, I would argue, the foundation of Umoja Health — building a relationship and not building a relationship like it’s a destination. Understanding that relationships evolve over time.

Trust is the equity of relationships. You build it up as you go through good and bad things together. Not just all good things, but the bad things, too. I think [what] we have forgotten in medicine, in healthcare, is our own humanity. We’ve forgotten that we are also simply people. I don’t care if you’re green, purple, brown, [or] whatever. That’s the one thing I have in common with everybody. We need to be making relationships with communities that are around us in the same way we would be thinking about and making relationships with our friends.

We don’t have to tell them all our personal secrets but we shouldn’t be thinking about those relationships as, “I have all the resources and you do not.” There’s that way in which we otherize the patient. It happens in medicine, just in that doctor-patient interaction. The doctor is coming with some information. The patients come in with a lot more information than the doctor could ever have because they’re living in that body every day. But there’s some way in which we exalt the doctor, [as if] the doctor could never be the patient, which is a ridiculous proposition.

Similarly, as institutions, when we partner with [the] community, we otherize them. There’s a lot of paternalism. There [are] things that we want to hide and don’t want to say. Failing to recognize that.

If we came with transparency and said, “These are the hard parts. Let’s work on the hard parts together,” that is going to build trust faster. Then it all looks good and everything we do is great.

We need to be making relationships with communities that are around us in the same way we would be thinking about and making relationships with our friends.

How can we start the relationship on the right foot?

Stephanie, TPS: What are some things people could say to be more transparent and kick off the right conversation to lead to a good relationship?

Dr. Rhoads: First of all, it’s an acknowledgment that this one interaction is not our whole relationship. This is the beginning. I will see you again. In the process, as a human being, I will be making some mistakes. You will be making some mistakes. We will have some miscommunications. But the commitment to the relationship is that we will work through those together. I think that’s what can happen in the doctor-patient interaction.

In the institutional interaction, there also needs to be some humility. We talk about truth and reconciliation. We want to do the reconciliation; we don’t want to do the truth. That’s the hard part. Part of that is getting out of the building and being in community in whatever way you can. You don’t have to be in community as the doctor. Be in community just as an individual human, experiencing life in the same geographic territory as other people but obviously having a different experience. I think that’s what helped Umoja move along.

I also think people buy into Umoja and link into Umoja because even though it’s focused on COVID for the moment, it came out of our relationship with our partners around cancer. They asked us specifically to focus on COVID when the pandemic hit and we said we will do that because we committed ourselves. Year-round — not just when cancer is a problem. Non-transactional — we’re not here just because there’s a study and we need you to get in our study and diversify our study. We’re here because we want to be in partnership. It’s year-round, non-transactional community engagement.

I don’t think people really thought about the non-transactional part. They think about being nice. It’s not about being nice. It’s about being on a shared mission and sticking around when times get tough.

We need to build relationships and that’s where you’re going to get people wanting to be part of the solution.

When you get caught in a problem that gets posted on social media of your institution or a representative of your institution doing something that none of us want to see happen, what needs to be done is a confrontation of that behavior, an admission that that was not only wrong but is not what we are intending to do, and to sit with the community that’s impacted and listen as they express their frustration. Then figure out together how you can take action to avoid it in the future. It doesn’t mean that we’ll be perfect. Again, there’s a disclaimer. We’re going to continue to make mistakes. But what you’re committing to is continuing to work together. That’s the investment that is absent in all this DEI and DEIA conversation — the commitment to humility and transparency is what is always, always missing.

With Umoja, we’re out in the community. I’m wearing an Umoja T-shirt just like the volunteers who are there, just like any other medical provider volunteer who comes out — we all look the same. It gets me back to what my aunt was looking for. She’s looking for her neighbor to be at the clinic, to be the person to welcome her. When [you] take away that self-exaltation, holding ourselves more important than other people because we have special knowledge, you end up with the ability to connect with people. For the person coming into that setting, you also get rid of the feeling like they’re going to be judged for their life choices. If they feel like they’re judged, they’re going to lie about their life choices. They’re not going to be totally forthcoming. They’re not going to feel that they have permission to be fully who they are. And that’s where I think we’ve gone wrong with all of healthcare.

We do not train healthcare providers [to see] people in their full humanity without judgment. We provide rules of what’s good and what’s bad, and then you judge the people who are doing it wrong. Then if you layer racism in there, you have a quicker judgment [of] different people because there is a belief that they are inherently not good or inherently better than other people. Racism can go both ways. It’s not just thinking people are bad. It’s any judgment at all.

We need to build relationships and that’s where you’re going to get people wanting to be part of the solution, wanting to promote your study, wanting to participate in your study, because that’s not the primary thing you asked. The primary thing you asked them for was a relationship.

Racism can go both ways. It’s not just thinking people are bad. It’s any judgment at all.

How can small steps lead to big changes?

Stephanie, TPS: What you just said is really powerful. This piece about judgment is huge and that’s what you cut through when you started Umoja. You were in the community. You were leading. You were modeling. Something as simple as not wearing a UCSF shirt. It’s a simple decision but it sends a message.

Because of the timing, COVID is where a lot of the attention was paid. Can you give an example of how what seems like small steps and small decisions can actually really change someone’s mind if you really want to get them involved?

Dr. Rhoads: I’ve been doing community engagement work since 1993 and in 2020, I had a number of eye-opening revelations.

We started Umoja as United in Health District 10. It was an offshoot of Unidos en Salud and I always have to give credit to Diane Havlir for the brilliance of bringing COVID testing into the community when people didn’t have access. We were working in Bayview, southeast sector San Francisco — a large African American population, relatively speaking to the rest of the city — and then Sunnydale where we picked up Pacific Islander communities and then Latino population all throughout.

I remember having a conversation with my department chair and saying, “It really strikes me that the tents for the testing efforts were all just white tents. There was no signage anywhere that said Public Health Department or UCSF and I think that’s actually why people were willing to come.” That was my suspicion.

Then to bolster that, a participant I was speaking to — I had no idea she had gotten tested at our site — brought it up and said, “The only reason I answered your survey questions was [that] my neighbor was the person asking the questions.” Throughout setting these pop-ups, we would track the volunteers who are working the site: Do they match the demographic distribution in the neighborhood? Are we capturing the neighborhood people? Are we engaging the neighborhood people? So that was a big deal when she said, “I only answered because it was my neighbor. Otherwise, I wouldn’t answer any of those questions.” The trust was already there. The relationship was already there so that gives us an advantage.

Engaging people in the process changes how people perceive who you are.

Once we became Umoja Health in late 2020, people were coming out to work together who had never worked together before. I didn’t know because there were these community-based organizations [that] would come together under this umbrella. Thank you to the Brotherhood of Elders Network who opened the door.

We would get out into the field and I would have to say to people, “I know you’re really happy to see people, but please don’t hug each other.” It’s still COVID. There was joy inside of the pandemic and that joy was for us, by us, or FUBU work. Community saving the community. Community delivering the services. Community being valued for what they bring to the table, which is a relationship we don’t have.

That relationship translates because what you could see happening in the informational sessions we were doing in between the service events was people really understanding COVID in their own terms, in their own ability, to explain why social distancing mattered, why wearing a mask mattered, what is exponential spread… People just started to get it on their own. And that was huge. I realized these organizations suddenly are working together and have networks that we haven’t even seen.

By participating in delivering the services [and] setting up the site with COVID safety in mind, these people are going to go home to their families, they’re going to be in their social settings with their friends, and they’re going to be talking like this because it’s part of what they’re doing. It’s not because they’re now a doctor. It’s not anything formal. It’s the informal influence, the informal authority that they have within their groups that they could use to start promoting uptake and participation in COVID mitigation.

By the time we finished our first run of Umoja in the fall of 2020, African American people had gone from being the lowest testers in the county to being the highest testers in the county. We didn’t even work the entire county, but we had people in our informational meetings taking that information to their networks. People started really emphasizing and highlighting as credible messengers.

Those are examples of how engaging people in the process changes how people perceive who you are. Now, we get a lot of calls like, “Somebody has cancer. We need a second opinion. How can we get into UCSF?” People who would not have otherwise even considered talking to UCSF. These are people from our Umoja community, COVID-focused, calling us about cancer.

It just goes to show that the relationship is what matters. They perceive that we care because we’re willing to come out, to employ community people, [and] to make spaces for the community to be an active and primary part of the solution. We’re not looking at people as needing transportation and child care or you’re poor and you don’t know anything and we’re ministering to you. No, we’re saying we need what you know because that’s going to help us get the information out and that is what is going to help move us truly toward health equity.

Stephanie, TPS: Everything that you just described is so powerful. Those were really incredible examples. At the core of it, it’s about really building real relationships. People can feel it. They know. They know when you’re approaching them and they feel like, “Are you coming in thinking you’re going to save me?” Let’s go in equally because that’s what we are.

How can we avoid otherization?

Stephanie, TPS: For people who feel, “Well, that’s the other community,” what’s the message about why it’s so important for everybody? We’re not only talking about lifting black Americans or Latino Americans or Asian Americans or Pacific Islanders. What is that message to people who don’t get that part?

Dr. Rhoads: Otherization is really central to how I think about any of the work that we do in any community. You can be a short white man who is not aggressive and be otherized. There are a million ways to be otherized. What I go back to is the way to avoid otherization is to recognize your own humanity because that is the link you have to every single other person on the face of this earth. And I guarantee if you spend more time, you’ll find other similarities and other commonalities so you don’t have to separate yourself in that way. I think that’s core to what the problems are in healthcare.

What I would also point out is Umoja Health in Alameda County focuses on the African American community but in San Mateo County, it focuses on the Pacific Islander community and the Latino community. It’s whoever comes to the table. [It] really is people-powered. It is whatever resources. It is the actualization of stone soup. Whatever you can bring to the table, that’s the soup we’re making and that’s the soup that we’re having.

The way to avoid otherization is to recognize your own humanity because that is the link you have to every single other person on the face of this earth.

If what you’re bringing to the table is your ability to access resources from other spaces, even better, but it allows an opportunity for everybody to fully be who they are and not have to be other. We’re in this together. Everybody is susceptible to COVID. Everybody can actually come to the table and not be judged, “Well, you’re not bringing anything and so we’re here saving you.” No.

You can volunteer. You can encourage people to come to the site. You can educate people with what you’re learning in the meetings. You can invite people to the meetings. Everybody can contribute something. Until we get a handle on that, on believing that, and on operationalizing that, we’re going to be stuck.

For now, the paradigm we have is some people are better than others and have more than others and they need to give to or minister to those who have less. It discounts the importance of the other. Baba Arnold Perkins, who used to be the director of the Department of Public Health in Alameda County and who is now the chair of the Community Advisory Board for our cancer center, says, “Everyone is a piece of the puzzle and every piece is important.” And recently when I talked to him, he added to that. He said, “And every piece is equally important.” And that’s what I think we really need to recognize.

Think about doing a puzzle. Get a 5,000-piece puzzle. You’re just tooling along. It’s looking really good. A piece falls on the floor and you don’t notice until you’re done. When that piece is missing, it ruins the whole puzzle because it’s missing and it’s only one piece out of 5,000. So every piece is equally important.

Everyone is a piece of the puzzle and every piece is equally important.

Baba Arnold Perkins

How can we deal with the lack of trust?

Stephanie, TPS: Some people say this lack of trust or even distrust specifically when we’re talking about the black community, as the generations go on with younger people, slowly that’ll take care of that. In your experience, you met a range of people in terms of age with the same lack of trust.

Dr. Rhoads: Trust builds at the pace of the relationship. Think about this: If you don’t have a relationship, why would you expect to have any trust? You shouldn’t. Think about your own personal relationships. You just met somebody. You don’t automatically trust them. It takes some time of building up how you work together [and] how you relate to each other.

Over the generations, you might think [that] young people are unaware because this happened so long ago. But actually, the young people are where it’s at because their minds are flexible. They’re open. They’re willing to see disparate treatment, privilege, and access to opportunities. They can see it.

What I have observed is that for the younger people, it makes them uncomfortable. They want things to be different. We did hear the vaccine was developed too quickly. There [are] nanobots in it. Don’t trust the government. We saw that across age groups — no question. But I do think that there’s an opportunity because young people are now interested.

Climate change is another disaster that adults are creating for them. Racial discrimination. Killings of various kinds of people who are at a disadvantage at the hands of police. They’re seeing that for what it really is. I don’t hear from younger generations trying to smooth it over and say it’s just miscommunication. That’s definitely something that happens in generations who maybe don’t want to hold the responsibility for what we have created. The young people didn’t create it so it’s easy to critique it.

It’s not really a lack of trust; it’s an appropriate response to a history of untrustworthy behavior. There are reasons to be suspicious, which is why it matters to be in community, outside our walls, because that’s where you can start to break down things that happened in the past because now, something’s happening in real-time.

It’s not really a lack of trust; it’s an appropriate response to a history of untrustworthy behavior.

What are the next steps?

Stephanie, TPS: There are so many cancers that disproportionately impact black Americans compared to other groups. I know it’s across health care and life, really. But in cancer specifically, what do you see as the next real feasible steps? Bringing the hospital out into the community, really showing that we care, and trying to build real relationships. Are there additional steps that we can take collectively to help address the inequities and the disparities?

Dr. Rhoads: If you address the inequities, you’re going to get rid of the disparities. I’ve written some papers to look at [the] delivery of care and when you get the right care for the right stage of disease, the differences by race [and] ethnicity go away. We’ve shown it in colon cancer, acute myelogenous leukemia, gastric, and pancreas cancer. We know that if you address the inequities, you’re going to get back to differences. And differences are okay because innately, we are different from each other. We’re not going to live the same number of years. Those differences are acceptable. It’s the disparities where you didn’t get what you needed and therefore you’re dying early — that’s what we’re trying to eliminate. Addressing inequities is going to get us there.

There is a process that is in play. Building the relationship is the beginning of the process. What happens when you’re in relationship with [the] community is the questions start to be centered around the community instead of centered around institutionalists. Because we’ve made the barrier between the institution and the community more porous, we can actually receive input and guidance on what research questions should we be asking.

What are people observing on the ground that we’re unaware of and are assuming a sterile condition under which these disparities are happening? For example, higher rates of cancer in younger people. What do we know about what’s happening on the ground? Often, we don’t know anything. We assume everything’s equal.

The next step is having the community influence the research questions. We’re working with Cancer Grand Challenges, which is an international award to the United Kingdom and the US. The National Cancer Institute and Cancer Research UK combined to fund 11 projects. I’m involved with one of them and the question is about cancer promotion. Are there environmental exposures that cause a mutation you’re already carrying that your body is keeping in check? We are all carrying millions of mutations right now, but we’re not a million cancers. Are there environmental exposures that are selecting a mutation and saying now you’re going to start growing, you’re going to be a tumor?

I think that kind of research is going to be so importantly informed by advocates and community partners because they’re going to be able to tell you stories about what’s happening in their neighborhoods. When we see cancer clusters, we can start asking very specific questions about cancer promotion in those specific spaces. Again, that’s another example of centering the community in the research question. We can apply our scientific approaches, which are all very cutting-edge, but we’re applying them to questions that are directly relevant to people who are living regular lives outside of our institution. The next step is developing questions that really hit home so that our results are relevant to the people that we think we’re trying to serve and be in partnership with.

If you address the inequities, you’re going to get rid of the disparities… you’re going to get back to differences.

Differences are acceptable. It’s the disparities where you didn’t get what you needed and therefore you’re dying early — that’s what we’re trying to eliminate.