Joe’s Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Caregiver Story

When Joe’s wife, Anna, was diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), he became her primary caregiver.

Joe recounts how he met Anna, her initial symptoms, the chemotherapy regimen she underwent, and how they thought she developed a secondary cancer.

Joe also discusses the mental and emotional toll of a loved one having cancer, processing trauma after everything settles down, and advice for other caregivers.

You’ve got to take care of yourself to take care of your patient. You’ve got to. You’re not infinite. You’re not just a well of giving.

This interview has been edited for clarity. This is not medical advice. Please consult your healthcare provider for medical advice.

Pre-Diagnosis

How did you meet Anna?

Anna’s from Budapest, so she was living there at the time that we met, and we were working for the same company. We were working for an international tech company.

I had just started the job. Actually, I was based in Los Angeles, but I think I was staying in New York at the time. I had just taken the job, and my first project was actually in LA and San Francisco, and she was a project manager, [or] account manager, and had to book me plane tickets.

We started emailing, and I was very taken with her Google photo, a tiny little circle, and I could see her bright eyes and her smile. I remember thinking to myself, “There’s a person at this company I hope that I get a chance to work with.”

We, oddly enough, started communicating (because we were binational) on LinkedIn and started flirting very heavily on LinkedIn of all places. That was our dating site. We did that for, gosh, like three or four months, where we were back and forth on LinkedIn, messaging every day.

So we met in LA for the first time. We spent a week together, and that was it. That’s all we needed.

Overcoming challenges together

It’s been kind of challenge after challenge, and I feel that we’ve been able to get over each one. At first it was, obviously, we were thousands of miles apart. Nine-hour time difference.

Then suddenly it was the pandemic, and we were both quarantined for almost a year before we were able to really talk about seeing each other again. Then it was citizenship paperwork and getting the right stuff in place for her to come over and us to start our life.

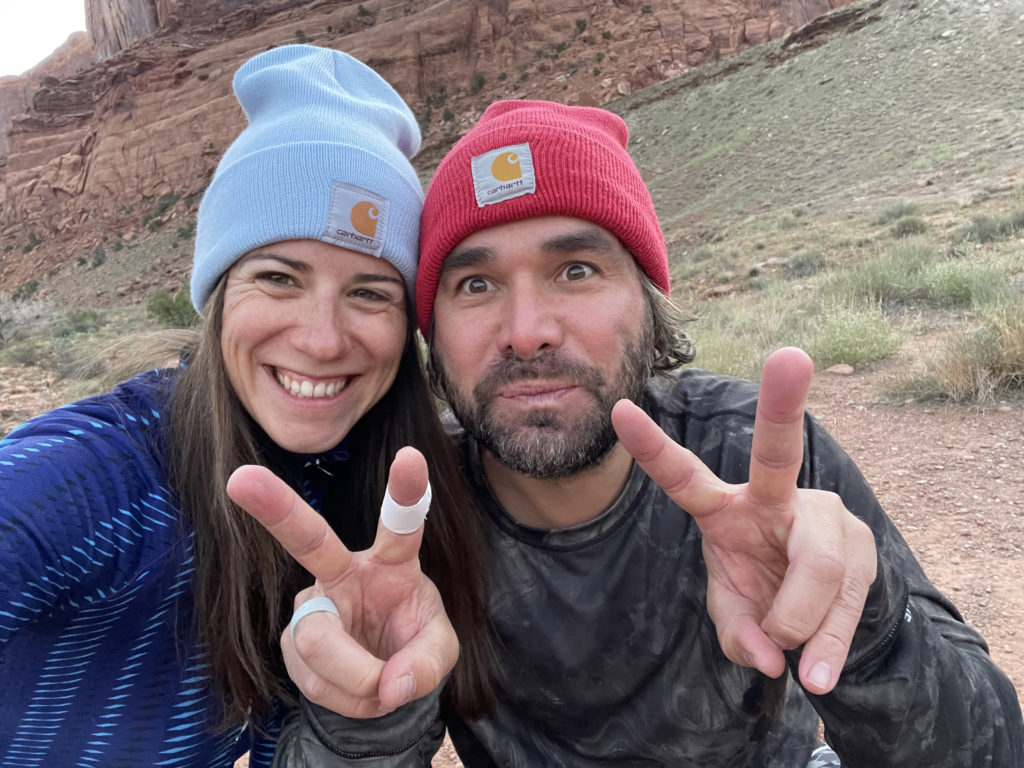

We got married last summer, and then it was five months of wedded bliss before her diagnosis. For a couple that’s relatively young and has been largely displaced for a good chunk of our relationship, we’ve proven our hearts to each other, especially through this last ordeal. [We’re] still going strong.

Anna’s 1st Symptoms

For us, it all happened so fast. Anna got COVID in October of 2021. Nothing serious, and she seemed to recover. We vacationed in Florida in November. In mid-December, I had a little bit of a work/social trip to Chicago. She came with, and we kind of parlayed it into a little bit of a mini vacay before the holidays.

In between November and December, she’d been really displaying symptoms of some fatigue. The only thing I could call it is kind of breathlessness. As a runner, she’s probably one of the fittest, healthiest people that I know. Suddenly, we would go on kind of one of our long walks or whatever, and she would start to get winded pretty quick.

For the duration of that, we really were kind of excusing it by, “Maybe it’s long COVID, or maybe it’s just ongoing symptoms from the COVID.” It was really easy to do that.

We were in Chicago for a week then in mid-December, and toward the end, she was really starting to have a lot of flu-like symptoms. We were walking around a museum, and she got very warm, very sweaty. It was kind of our last night there before we came back to Colorado.

She had a really heavy menstruation, which for female patients that have [periods], that’s something to look out for, for sure. That’s like a big, big indicator of your blood counts being kind of out of whack.

We at first, again, didn’t necessarily think anything of it. We flew home. It was a week between the time we got home and when we went to urgent care, and during that week, things got increasingly worse.

Escalation of symptoms

I think with the acute blood cancers, with acute leukemia, that’s the deal. You can go from a kind of dismissible, less than 10% blast count in your bone marrow to 75% in like two, three weeks.

So in that week, it was like all of a sudden she was out of breath when she walked up the stairs. She was out of breath after she washed her hair in the shower.

If there’s one big indicator, she started to develop all these mystery bruises all over her legs and torso.

We got into the kind of WebMD black hole, and they tell you it’s usually not the worst-case scenario, and I’m looking at leukemia like that’s the worst-case scenario. When the bruising happened, it sort of started to become undeniable. We have to get this checked out.

She was even starting to develop a little bit of the petechiae, the little red dots around a bruise, like lining a bruise. That’s another thing to look out for, or some of the gum line perhaps. We didn’t want to be alarmists, but we were like, “Maybe you’re severely anemic. I don’t know.”

At the end of that week — it was a Sunday — we went to urgent care because we just wanted an answer. It didn’t get super alarming until that last week, and [in] five days we went from zero to, “Holy crap.”

What went through your mind when you found out it could be leukemia?

That’s why I think the concept of early detection is so important to preach and also so important for all of us to accept, because nobody wants this to be the conclusion. We certainly didn’t. I certainly didn’t.

Hindsight, I look back, and I think in my gut I knew. We’re on WebMD, and I’m seeing like, “Okay, at one end of the spectrum, she could be anemic. At the other end of the spectrum, it could be leukemia.” I think in my gut, I was like, “This is bad.”

But I think at the time, the denial, self-preservation, survival, your brain is looking for — I mean, your survival brain. I think the lizard brain, that small voice at the back is going, “This is going to be bad.”

But the reason brain, the human brain, this evolved brain is like, “Nope, it’s going to be fine. It’s all good.” I think there’s a lot of conflict there while you’re in it.

Probably there was a lot of underlying anxiety, certainly some sleeplessness, and just some dread. I think that I was still trying to talk myself into believing that it was all going to be fine.

Anna’s Diagnosis

Heading to the hospital

Again, the timeline for us was so compressed because we went to urgent care on a Sunday, and then by Sunday night, we knew pretty much what the deal was. Thank God for the medical teams that were in place.

We were very lucky. There were some personnel, whether doctors or nurses, in place who kind of took a look at her symptoms and knew to ask for not just the basic blood panel, but a white blood cell count.

It was a Sunday night, so it got sent over to the labs and then to the ER, and there was no guarantee that there would have been someone there to read the results. Luckily, there was a lead doc in the ER where we lived who got the labs, called Anna about 9 p.m. Sunday night, and said, “This is not good.”

They told her, “Bring your husband, pack a bag, and don’t take more than an hour because we got to get [going].” It was very quick. At that point, we get that call from the doctor, and we still don’t know exactly [what it is]. So we drive to the hospital [in] middle of the night, clutching hands, freaked out. Of course, I’m still trying to comfort her.

I don’t want to lose the memory or what we’ve learned of any of this, but if I could kind of scrub one clean, I think that first night would be the one I would say, “Can you just nip that out of my brain and toss it in the trash?”

Unofficial diagnosis

I remember her trying to take a shower and put stuff in a duffel bag for us to drive to the ER, and her just shaking and so afraid of not knowing what we were going to hear.

We drove to the hospital. They took her into the ER first to kind of see what was going on. Then they called me in. They had told her there’s about an 80% [or] 90% chance that this is leukemia, that this is cancer. They told us right there that that was the greatest likelihood.

I know that she doesn’t have a very clear memory of it. It’s very foggy for her. I probably also have a very foggy memory. I know there was a lot of time. She didn’t board the flight and I didn’t leave the hospital until like probably 2 in the morning, and I know that we went there about 9:30 or 10. I don’t remember it being three hours or so, but I remember snippets of it.

She has no family history. We had no reason even going into the onset of symptoms that this would be the outcome. I think it was just like absolutely 100% shock at first. We were both in shock.

I remember that she called her mother in Budapest to tell her. I remember I called my folks, and I remember Anna [said], “If you want to get out, now would be the time.” And I was, of course, like, “That’s ridiculous.”

Being transferred to Denver

The ER doctor was incredibly reassuring, and we got very lucky because of Anna’s oncologist’s association with this hospital, even though he’s headquartered in Denver.

We were very lucky that they had a bed up here where we are at the Colorado Blood Cancer Institute. Again, we got very lucky, looking back.

They kind of gave us the rundown. It all happened very fast. At the time, this was all happening down in Durango, Colorado, which is about six hours down in the southwest corner. They called Denver, they arranged for the bed, and they arranged for a med flight.

Unfortunately, they encouraged me not to fly up with the med flight because there were still COVID stipulations in place, and we didn’t know if I would be allowed into the hospital once we got there.

Processing the likely diagnosis

We decided that I was going to go back to our house, pack a bunch of stuff, and then drive up to Denver first thing in the morning.

I kissed her goodbye when the paramedics came in to load her up into the ambulance to take her to the airport.

I do remember walking out of the ER, getting into the car, driving back to our house, and crying. I’m angry.

You’re in a fit of rage because you’re like, “This is unfair,” and I’m kind of lamenting that. I have a distinct memory of driving and crying, and I’m mad at the universe.

And then all of a sudden I just stopped crying, and I was like, “I can be angry, but there’s nobody to be angry to.”

Her having this or not having this is not an argument that I’m having with anyone. Is it unfair? Sure. Yeah, absolutely. It’s all unfair.

This diagnosis is unfair for everyone, and I’m not saying that doesn’t matter. Everybody has to go through that. Every patient and all of the people who are supporting the patient have to go through that anger and resentment and fury, the why. But the why, why, why? There’s not an answer, and there’s nobody to appeal to.

I went back to our house, and I packed our bags.

»MORE: 3 Things To Remember If Your Spouse/Partner Is Diagnosed With Cancer

Official diagnosis

Anna and I were together at the hospital there, and we got the diagnosis from the oncologist, which was the next day.

He came in and said, “We know it’s leukemia, and we know it’s acute lymphoblastic leukemia. We know it’s B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, Ph-negative. We know exactly what it is, and we know exactly how to fight it. Here’s the treatment protocol.”

Once you accept the diagnosis, then it’s just a matter of kind of the logistics of reckoning with everything else. I have also said that a situation like this, when it’s life or death or cancer, everything’s sort of easy because all the questions are gone.

It’s just a matter of like, well, we have to do whatever we have to do to treat her, to fix this. Everything else kind of falls in line after that. It’s just a matter of how we do it, what we do, or when we do it.

Role as a Caregiver

How did you process your emotions?

I think I probably still am. I think I’m just starting to process stuff in a productive way now. It was shocking. I also think we were a little bit lucky that our diagnostic timeline was so short.

We did have to do a lot of stuff very suddenly. We had to move overnight, we had to figure out job stuff, and we had to do everything overnight. There wasn’t time to dwell on anything. There was only time to act.

The trauma often doesn’t happen while the traumatic experience is taking place. Trauma is a byproduct. It often happens after.

Even her oncologist said, “You could go get a second opinion, but I don’t think you have time.” She was about a week or two away from a stroke. He was like, “I think we should do chemo, and it’s going to take three years.”

There was one moment where Anna was like, “I can’t do this for three years,” and I was like, “Well, we have to. There’s no alternative right now.” We ultimately just had to do [it], so I think we both clicked into a survival mode immediately.

Processing after treatment

Just given the structure of her treatment protocol, it gave us a lot of milestones to hit and a lot of goals to work toward. She was in the hospital for 30 days while they tried try to induce remission. We knew that from day 1 to day 30, our goal was for her to be in remission by day 30.

So we had that and then it was just a matter of getting through each course [or] each phase of treatment. It put us in a state of fight or flight for nine months.

What I’ve said not only about my experience, but what my wife agrees about her experience is that the reality is that the trauma often doesn’t happen while the traumatic experience is taking place. Trauma is a byproduct. It often happens after.

It’s very complex because by the time the experience is over, the people around you are ready for you to be better. But that’s often where the quality of your mental health or emotionally you might be at your worst because you’ve only just started processing.

Being a caregiver during Anna’s treatment

Her treatment protocol kind of varied. Overall, this particular protocol is one of the most intense, but course to course, it kind of varied in intensity. So she had some courses where she was doing okay, and then she had some courses where she was barely conscious.

The amount of care I was giving was regulated based on that. Regardless, there was a lot to do because if she wasn’t in the hospital, we were at clinic like 3 to 5 days a week. There was a lot of logistics.

Stocking the kitchen with the right foods, making sure that we had stuff that made her comfortable, fixing meals, getting her to the bathroom or whatever, getting her showered if need be. And then we were driving up to the clinic or the hospital for every appointment.

I think I sort of thrive in periods and stretches where I have to satisfy logistical demands. So I think in a weird way, I was sort of at my best when the demand was high. I think that even though I was conscious of the fact that I needed to look out for my mental health, I didn’t put a lot of energy into it until much later.

Taking care of your own mental health

If I were going to tell new caregivers or caregivers just coming out of a loved one’s diagnosis, I would say get into that very early, and don’t rely on one method. I think I sought out a therapist maybe, and I went to a couple of sessions of therapy. It felt a little like putting a Band-Aid on an open wound.

I was like, “Well, this feels like a waste of time,” and then I just didn’t do it then for the bulk of the year. It wasn’t actually until Anna started to get better [that I went back].

We weren’t really out of the jungle until maybe November when her current treatment option was introduced to us as a way forward.

It has been since then that I’ve really noticed and maybe since a little bit earlier that I’ve really noticed the challenges of my mental health. It has kind of spurred me into action for my own sake.

I sought out not only therapy, but maybe psychiatry and a little medication, a little bit of self-care, and a little bit of peer-to-peer, making sure that I’m part of talking to other caregivers [and] making sure that I’m accessing any resources that I have available, of which there are many.

The other thing I would encourage caregivers to do. Don’t count on one path for mental or emotional wellness.

You might need a variety [or] a combination of those things to really keep your self functioning. It may not just be talk therapy, and certainly don’t rely just on medication.

Connecting with other caregivers

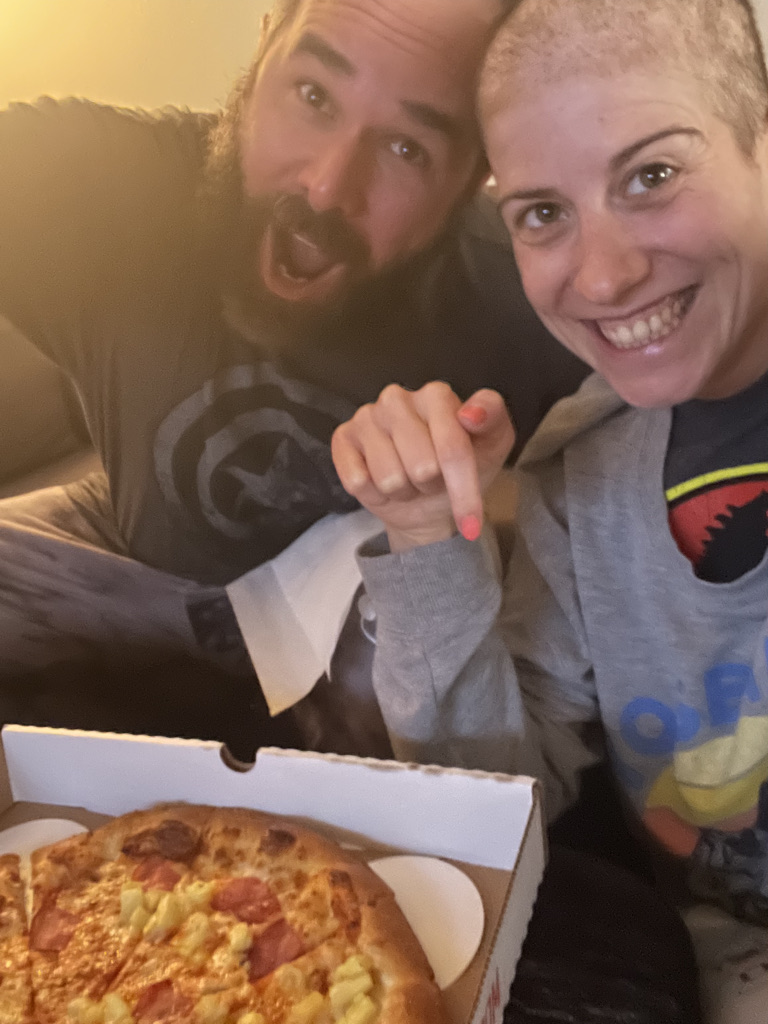

Talking to other caregivers or hearing other caregivers’ stories and the cancer community at large. A lot of connections that we made online, a lot of connections we’ve made in the Denver metropolitan area, a lot of international connections that my wife has made, thankfully, through social media.

We talk a lot about social media being the bane of our existence, but Instagram literally kept my wife plugged into the world while she was trapped in a hospital bed. I wish we would have leaned into it sooner.

I think there’s a reluctance to do that, too, because it’s like an admission of the people don’t want to be reminded that they’re [in the cancer community]. Everybody says, “The cancer community is the best club you never wanted to be a part of.”

But once you kind of give yourself over to it and you’re like, “Oh, there’s amazing people here who are ready to care for you and support and help and offer guidance,” that kind of changes the outlook a little bit.

Caregiver Identity

Advocacy for caregivers

Anna and I are both trying to move into a stage where we’re giving back to the community, doing a lot of fundraising. She’s trying to do a lot of awareness. We’re trying to preach the early detection.

I’m trying to do a little advocacy for caregivers. There’s a lot of good stuff going on for caregivers, but the role of caregiver [is] really complicated. I think it’s for a couple of different reasons.

Caregiver not taking care of their own needs

I think an inability to or a reluctance to recognize and identify personal needs, to make an attempt, [and] put in the effort to satisfy those needs is inherent to caregiving in those scenarios.

When it’s a loved one that has a diagnosis that’s as serious as cancer, our human instinct — maybe not instinct, but our human response — our socialized response is to say, “What do my needs matter when my loved one has cancer?”

The problem with that is — and it’s understandable — it seems to be on the surface evidence of compassion and evidence of recognition of the other situation. But simultaneous to that, it’s also incredibly unhealthy to go into a situation like that denying your own personal needs.

If you’re not good, how are you going to take good care of your loved one? Also, it’s just a denial of personal needs.

Mental health issues for the caregiver

This is something I think we probably don’t talk about often enough, but I think it’s very interesting, and it is starting to come up. I was on a great webinar that Leukemia and Lymphoma Society put together.

On the webinar, we talked a lot about how if you’re in the trajectory of a diagnosis or the cancer journey and if you’re lucky enough to avoid bereavement, oftentimes it’s in the stage when the patient’s in survivorship that there’s the biggest spike of depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation, and serious degrade in mental health among caregivers. [It’s] when the patient’s getting better.

Anna and I talk about it all the time that as she’s gotten better, we’re a little bit like ships passing in the night because not only is she kind of forged with this new identity as a survivor, but she’s also getting what she lost back. She’s getting her health back. She’s slowly building back up.

Creating an identity as a caregiver

For the caregiver, this role that you have sort of adopted has become your identity, because in this particular instance, caregiving kind of involves helping to keep someone alive.

Within that pursuit, I think there’s also a lot of conflict because in the context of the hospital, the clinic, among the care team, or in the presence of the oncologist, you sort of are aware of the fact that you’re useless.

There’s literally nothing you can do. I think there’s a lot of conflict there. You had this identity that you’ve sort of adopted in order to keep your loved one going alive [and] taken care of. It’s kind of like sand through your fingers. It’s slowly slipping away.

As that happens, as you become less needed in that way, and I know for me as I became less needed.

It’s a loss of purpose, and there is a depression to loss of purpose. You start to feel sad at a time when you know intellectually that you should be celebrating.

My wife is not only an independent person, she’s the caretaker and caregiver in our marriage. I’m the caregiver in this situation.

Once she starts feeling ready to kind of be again, the moment she starts feeling better, she’s like, “I can do this. I’ll take care of this. I’ll take care of this.” I was like, “Wait, that’s my job. Please.”

Losing your identity of caregiver

It starts to kind of slip away. It’s a loss of purpose, and there is a depression to loss of purpose. You start to feel sad at a time when you know intellectually that you should be celebrating. So you’re like, “What the hell am I feeling right now?”

I’m not saying that this happens to all caregivers. Certainly, I’m sure there are caregivers out there who are like, “What are you talking about?”

But it’s what I experienced, and I have talked to other caregivers and talked to other medical professionals who identify that this is a thing that a lot of caregivers go through.

I think it’s important to recognize because, again, I think during it, the shock of the diagnosis and the shock of treatment and the shock of this new life can prevent the caregiver from getting care, taking care of themselves, seeking out support.

This moment, when the demand on them is less and the risk for some mental health struggles might be highest, that would be the time when all of this stuff maybe they avoided doing or we avoid doing becomes even more critical to make sure as you build to a new normal, you’re not totally broken as a human being.

Secondary Cancer Scare

Treatment protocol

I was struggling so much. She was off chemo. We had a very difficult July and August. She was back in the hospital for 10 days with a terrible infection while she was immunocompromised. Then we had this crazy diagnostic scare where they thought a secondary cancer presented itself.

Turned out to be untrue, thank God, although I think I still have struggled to let that go.

She was on a treatment protocol: ECOG 10403, if anybody is familiar with that. It is a pediatric chemo protocol and very useful in young adults. The cure rate in kids with this particular protocol is something like 85 to 90% now. So it’s just like they perfected it, and it’s proven very effective in young adults as well.

[It’s] very, very intense, obviously, because the young body can withstand it. There are three phases. For female patients, it’s typically a three-year process. I think for male patients, it’s a four-year process. And there are three phases.

There’s induction, which is a 30-day process to try to induce remission. They bombard the body with enough chemotherapy and enough steroids to hopefully get the percentage of cancer in the marrow down to zero.

Then second phase is consolidation, and that’s a very substantial period, something like I think a six- or seven-month period of varying chemotherapy and varying treatments.

Then at the end of that, the patient moves into a phase called maintenance, which is a still significant but lower-grade dosage, less frequent treatment. It’s for a further two years.

The methodology is like you’re grinding the cigarette butt into the cement until it’s nothing. Anna had just come to the end of consolidation and was ready to move into maintenance for — I think I mentioned — acute lymphoblastic leukemia, ALL.

Bone marrow biopsy

She had a customary bone marrow biopsy as we ended the course, ended the phase, to make sure things look good. Her body had been incredibly responsive at every phase, at every stage, responding to treatment in the way that it should. We kind of assumed this was going to be no different.

This was end of August, and we went in for a routine appointment with her oncologist and our nurse coordinator to go over the biopsy results. There were a couple of kind of weird things.

Myeloblasts

In this particular situation, the biopsy had showed a percentage of myeloblasts, which are an immature blood cell. That’s all leukemia is. Leukemia is a mutation where evolving cells kind of stop at a very immature phase, then they just start to replicate, and they can take up all the room in the marrow.

There was a troublesome percentage of myeloblasts that seemed to indicate the presence of acute myeloid leukemia, which is the other acute leukemia.

The explanation was that somehow — because leukemia is a tricky— it looked like because of this targeted chemotherapies for lymphoblastic leukemia, the leukemia had mutated or kind of switched it up to avoid the targeted chemotherapy.

He was obviously like, “We can treat this, but it’s going to be a bone marrow transplant.” We had the weekend to kind of process, but then she went back into the hospital on that Monday.

The plan was she would do 30 more days of chemotherapy to induce remission for this AML, and then they were going to start work on getting a donor for a bone marrow stem cell transplant, which the timeline on that can vary. Beyond the 30 days, we didn’t know what the future of the treatment would be.

Processing the possibility of a second diagnosis

So that was really just doing the diagnosis thing all over again. Take the weekend to process. That didn’t really happen. It was just a lot of crying and, “What the hell?” And, “How could this be?”

Anna has patient amnesia about that. I really struggled with that because the brain starts to do the worst-case scenario, trying to protect you from how this could play out in the worst ways.

It was a really difficult weekend, and then we kind of just had to get the fighting spirit going again. She got into the hospital, and we were doing that. At this point, we were veterans. We kind of are more comfortable maybe in hospitals and clinics than out.

They kept kind of prepping her for when the chemo would start, and the oncologist came in and the team, and we walked through this whole protocol and how this would happen. We met with the transplant coordinator, and we talked through all of that. Lot of dread and reconciling.

Well, long story long and then short. It took about another two months to kind of guarantee that this wasn’t AML.

Post-cancer scare

What happened was what looked like the possible onset of AML was actually bone marrow that had been decimated by chemotherapy and was rebuilding in a healthy manner. It was a small percentage of blasts because her bone marrow was coming back from having very little.

She was off chemotherapy for like two months and really just starting to feel better. I think it was during those two months where I felt I was doing the worst. I think that’s where I kind of started to recognize the need to get my shit together and start working on myself.

It became pretty clear that we were going to maybe come out of this. It never goes back to normal, but you start getting back to your new normal. When that’s clear, I wanted to be ready for it. So that’s a lot where I started to seek out a little more help. A lot more help.

Advice for Caregivers

Seek things that make you strong

I think when this first happened to us, I got a lot of advice that was something in the vein of like, “Stay strong. Be a rock.” And not that that’s wrong, because if you’re the caregiver, you do have to. Your loved one has cancer. You do have to be [strong].

I think “be a rock” is terrible advice because what does that mean? There’s nothing that rock does. It just is. It is a rock. That’s why a rock can be a rock, because it is one. I’m a human.

Very, very lucky to have a relationship with my wife where we kind of don’t tolerate holding anything back, and we’re very open and upfront. I think advice-wise, I would say, “Not be strong for the patient. Do everything you can for yourself to make sure that you can be strong for your patient.”

I think that’s the advice. You can’t just be a rock. You can’t just adopt strength, and you can’t just decide to be strong. You’ve got to do stuff that helps you be strong.

Take care of yourself

You’ve got to take care of yourself to take care of your patient. You’ve got to. You’re not infinite. You’re not just a well of giving. Are you going to have to give a lot for longer? Absolutely. [It is] going to be exhausting and tiring, and you’re going to have moments.

That’s the other advice, and not to be too long-winded about it, but I think the other advice is whatever you’re feeling is justified, within reason. I think sometimes [as] a caregiver, you have those ideations where you’re like, “I want to run away,” or, “I want this to be over in some way,” or, “I want to get away from this.” And of course you do. Of course.

I think then denying that or feeling bad for feeling that is doing you a lot more harm than you might think. So I think accepting what you’re feeling is also important, but I think the big one is just you’ve got to do what you can to be strong. You can’t just be strong.

Inspired by Joe's story?

Share your story, too!

More Spouse Caregiver Stories

David Garrigues Ronda, Spouse of Laurent Gemenick, Bladder Cancer Patient

“Talk to family, talk to friends. Ask for help. Don't be alone. And above all, don’t miss any doctor's appointments.”

...

Lung Cancer Caregiver Series Episode 2: Stephen and Emily Huff's Candid Conversation

"We talked, and I remember saying, "What if we have kids and what if I die?" And you were like, "What if you live?"

...

Emily Huff, Spouse of Stephen, Lung Cancer Patient

“Emily's the reason why I’m alive today. The treatments have kept the cancer at bay, but she's the one who’s kept me living, breathing, and enjoying life.”

...

Blair D., Spouse of Brain Cancer Patient

“Find other people who are going through the same thing you are. This journey is very isolating and very lonely.”

...

Nat G., Spouse of Bladder Cancer Patient

“You have to become selfless as a caregiver. You have to assure that person that you are there for them.”

...

Kyle Appleford, Spouse of Lung Cancer Patient (Metastatic) with No History of Smoking

“Ask for help. Don’t be too prideful to accept the help. I wouldn’t be here without all the support from family and friends.”

...