Laura’s Stage 4 Renal Cell Carcinoma Kidney Cancer Story

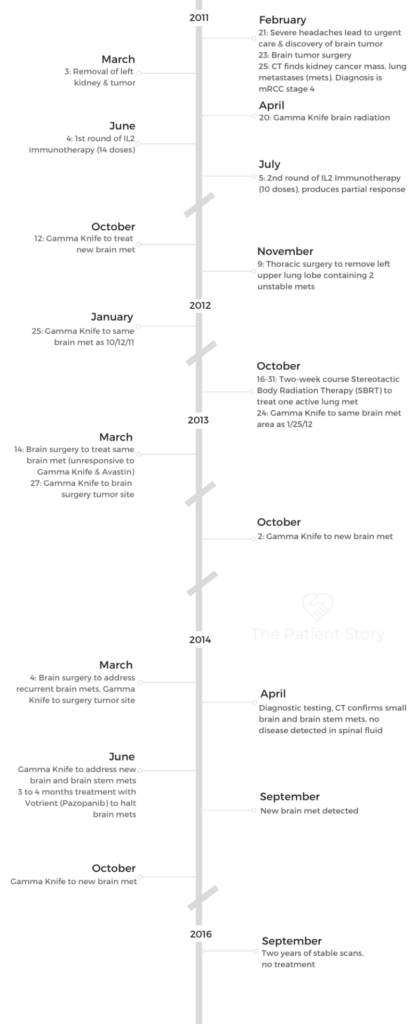

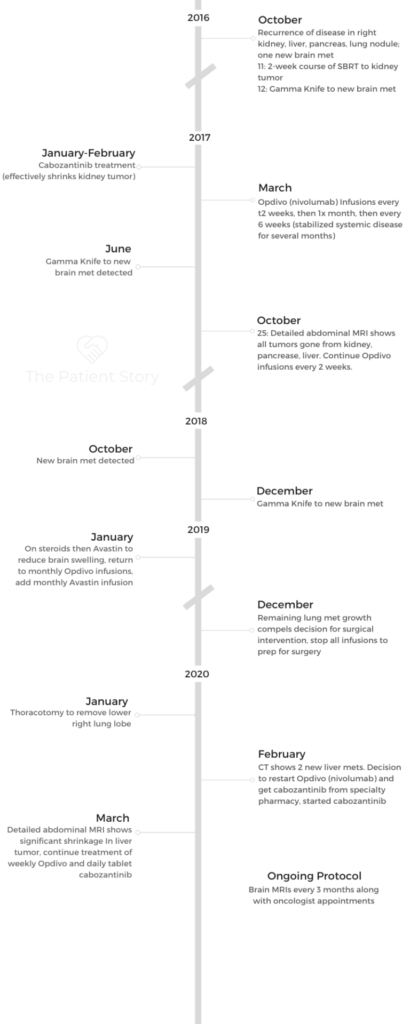

Laura shares her stage 4 metastatic kidney cancer story, clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) subtype, and details how she made it through extensive treatment. That included surgery, radiation, and immunotherapy.

In her in-depth story below, Laura describes navigating a cancer diagnosis like a chronic illness over a period of many years. She highlights issues like dealing with no standard of care, how she manages scanxiety, and how she dealt with telling her young son about the cancer diagnosis.

- Name: Laura F.

- Diagnosis (DX):

- Kidney cancer

- Renal cell carcinoma

- Clear cell

- Age at DX: 45 years old

- 1st Symptoms:

- Headaches (caused by brain tumors)

- Treatment

- Surgery

- Radiation

- Immunotherapy

- Tyrosine kinase inhibitors

- Monoclonal antibodies

This interview has been edited for clarity. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider for treatment decisions.

Find it somewhere inside of you to get back up. Every day, do something. You can put one foot in front of the other even if you’re still recovering from surgery.

Find whatever that is, that place within you that allows you to pick up your head and face the next day. That’s what I’ve learned.

Laura F.

First Symptoms

Describe when you knew something was wrong

In my case, I was diagnosed with stage 4 kidney cancer by way of brain tumor. I don’t know how often that happens, but for me, what that meant is my main primary symptoms were headaches. For several weeks, many weeks, I managed the headaches with ibuprofen.

I was working as a corporate attorney in a full-time position. My boss was on her own leave of absence, so I had stepped into her shoes for about 12 weeks. [It was] a higher-level supporting role, so I was very busy. I managed the headaches with ibuprofen and caffeine.

That was my primary symptom, but those headaches became increasingly severe over many weeks until they really started to affect my sleep.

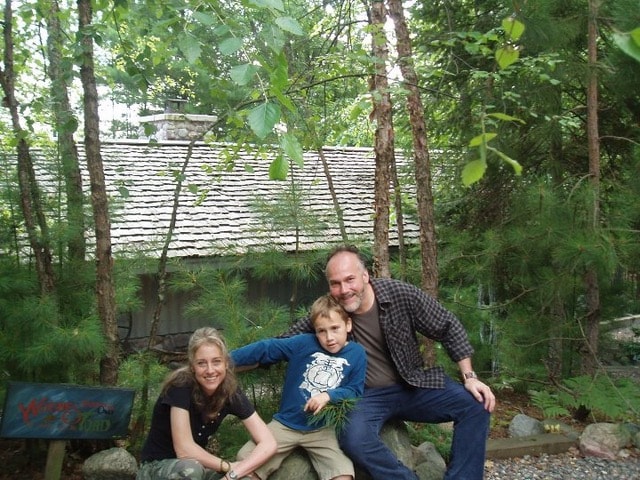

I had a small child at the time, who’s now 16, but he was 7 years old when this cancer experience was beginning. There were bedtime reading stories and soothing him to sleep.

Those kinds of things started to become more difficult for me. I couldn’t keep my eyes open. My headache would keep me from engaging fully with him. That’s when I really started noticing it more.

Then I had a couple of episodes of very extreme headaches. They certainly were warning signs, but they would pass. It was easy or convenient for me to overlook them to some degree.

That was the primary symptom I had; they were intermittent. They would come and go, and then they got increasingly worse. Then I had a couple of very distinctly severe headache episodes.

When did you seek medical care?

I actually had scheduled an appointment with my primary care doctor to say, “Let’s have a physical and talk about the headaches.” Before I could get to her, I was out on a winter day with my husband and my son after a big snowstorm. We’d gone to go get salt for the sidewalks.

We were actually in the store shopping when I had an episode of a very significant headache. It made me sit down. It made me really concerned. I didn’t know what was happening. I didn’t lose consciousness, but it was not right.

I just looked at my husband, and I said, “Do you think I’m having an aneurysm?” He wasn’t sure but said we should go to urgent care, which happened to be across the street, basically, from where we were.

That’s how it all started.

What happened at urgent care?

I got into urgent care within 20 minutes of having been shopping with this headache and saw an urgent care physician. They triaged me immediately to the front of the line. Obviously, they thought there was something going on that I didn’t recognize.

From there, the urgent care doc spent a lot of time with me, checking my reflexes, looking in my eyes, things like that. Then she just surprised me and said, “Listen, I want you to go get an MRI so that we can rule anything serious out, and we’ll probably be back here to talk about a migraine,” which I’d never had.

It was really sort of an episodic situation, where I was out and happened to be near the urgent care, and that’s what happened. Then we went for the MRI.

What happened with the MRI?

We took our son to my sister’s and dropped him off, thinking we’ll be back to pick them up shortly. I went for the MRI. By the time I got out of the MRI tube, the doctor I was seeing at the other clinic urgent care was on the phone and waiting for me.

He’s the one who I had just met that day. The urgent care doctor said, “Listen, there’s something in your brain, and it needs to come out. A neurosurgeon has already seen your film while you were in the [MRI] tube. He’s on his way to meet you at the hospital.”

The Cancer Diagnosis

Processing the news

I was just sort of on autopilot. I’m being told what to do.

The doctor was on the phone with me, and she said that they’re going to come in and escort you to the ER now. I was like, “Who’s they?”

At this point, I’ve got a glass door between me and my husband. He’s looking at me on the phone, and I’m looking at him while I’m hearing this information.

It was just surreal. I didn’t have the context for it, and so I just followed the directions. She said, “Can you do this? Can you go with them to the ER?” That’s what happened.

I got off the phone. These people showed up from the ER, flanked me, then literally walked me to a bed in the ER, and put me in the bed.

They hooked me up to an IV, which I wasn’t exactly sure what it was. I was told I had so much swelling in my brain, from whatever this was that they needed to control the swelling. That’s what the IV was for. That’s why they wanted to get me to the emergency room to be treated with steroids.

The steroid, dexamethasone, is very powerful. They use it for brain tumors to contain the swelling. That’s what happened, and I ended up in bed with an IV and waited.

I was waiting for the neurosurgeon on call to come and see me to describe what was going to happen.

How was your neurosurgeon?

He was very calm, kind, and very circumspect about what he could see in the imaging. He said there was a mass, it needed to come out, and that we wouldn’t know what it was until they could do the pathology on it.

He was not giving me any statistics or data or what he thought it could be. He was trying his best to keep things as neutral as possible until we knew more, but it was clear by then we knew it was very serious. It was described as about a golf-ball-sized mass.

Pretty much all the amount of swelling in my head put me at high risk for having a stroke, passing out, becoming unconscious, or a variety of other neurological complications. That was why I needed to be on the IV medication in the ER.

The neurosurgeon said he needed to do surgery to remove the mass as soon as possible, but he couldn’t do the surgery until the brain swelling came down. That meant I needed to be on these powerful steroids for about 2 days before he could actually do the surgery.

What were the pathology results?

The initial pathology looked good. There were no cancer cells in the initial pathology. When a couple days later a different doctor who I had never met approached me to say that they needed to do more imaging of my body, I was confused. I didn’t know why since I had already been told there was nothing. There was not a problem. It was benign. They called it a meningioma.

But then the plan changed.

I was confused and wasn’t being told why more tests were being ordered. I did the test, and yet a different doctor came in to talk to me after those tests were completed to tell me. By then, my husband was with me. He informed us that there was a mass in my kidney.

It was diagnosed as renal cell carcinoma by the pathology, and they confirmed that by finding the mass in my left kidney.

This is part of why I think that patients who encounter the system in this way are disadvantaged, because this doctor was not an oncologist.

She was a general hospital doctor coming to tell me my test results. Then the next step was to engage the oncology staff within the next few hours.

Then the oncology team arrived at my hospital room to talk to me more about what these results meant. Clearly, it’s painful. I had a softball-sized tumor mass in my left kidney that was related to the brain tumor they just removed, so it was a pretty obvious message that this was a stage 4 situation. The cancer was metastatic.

Meeting the oncologist

The discussion was mostly about potential treatments. The first part of the discussion was the need to surgically remove the tumor in my kidney, which necessitated conversations about who was going to do that and when and where.

Then the rest of the conversation really was about likely treatment options. This is the first time I heard the name of at least one type of drug, Sutent (sunitinib).

At the time, that seemed to be a relatively recent drug that they were using to treat advanced kidney cancer in this type of situation. I didn’t really understand it specifically, other than there seemed to be some hope that my situation could be controlled at some point with a chemical treatment method, on top of surgery and radiation. That seemed to be part of the picture.

Kidney cancer diagnosis

They knew by the pathology, renal cell carcinoma, it was kidney cancer. They knew that it was connected to the brain tumor because they’d had enough time to study the pathologies by that time.

Processing the diagnosis

The first thing I did was I hurried the first doctor to get out of my room, so it wasn’t very good. I don’t know. I don’t know who you are; I want to talk to my doctor. I don’t trust you because that’s not what they told me before.

It was a pretty irrational, perhaps emotional, reaction because it didn’t make sense. Eventually, when I was surrounded by my family, including my husband, to get the information from the oncologist, fortunately I had people around me who could also ask questions about what did some of these things mean.

At that point, it really was just sort of getting to the next step for me, which was having the surgery to remove the kidney, tumor, and my kidney, which happened about 2 weeks later.

»MORE: Patients share how they processed a cancer diagnosis

Breaking the news to loved ones

As an attorney, I’ve got a lot of experience separating my emotions from my logic. I think some of those sort of skills kicked in. I was able to articulate at least to my parents when I had to call them and tell them what was going on and ask them to come to the hospital room to be present with the oncology visit. I handled that.

Then, in the midst of all the information that was being told to me, I listened, I think, more than I talked.

Other than that, I was just trying to process the information. In retrospect, I just was probably in shock, and so I think I went into a mode where at some point I felt like it was too much information.

I didn’t really understand it. I didn’t really know exactly what to do with it. But my husband was there, and he was very supportive.

»MORE: Breaking the news of a diagnosis to loved ones

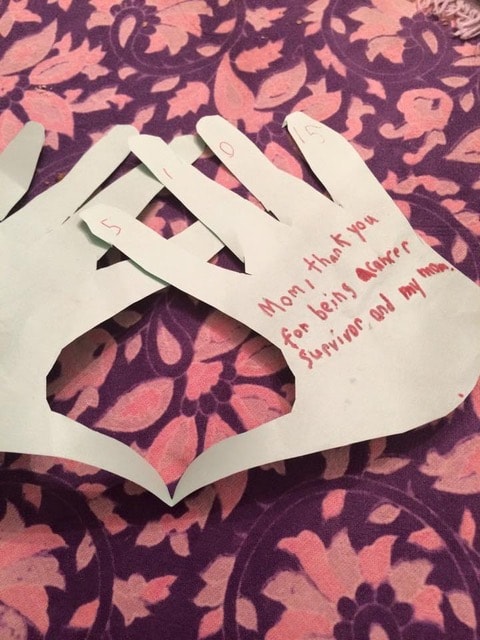

How did you break the news to your son?

Kids know a lot more than we think they do. [That’s] the first thing I’ll say. It’s important to remember that I think, because our view was he already lived with me and knew that I was having headaches.

Then he knew I had a surgery because they found something in my brain that was causing those headaches.

Once the diagnosis came, there was more information that we had to put together for him. We had already concluded we needed to be as honest as we could with him so that he could understand that we were not hiding anything from him, but without telling him too much.

While I was in the hospital getting surgery for my kidney, I believe that was the first time I’d spoken with a social worker, who came to visit me in my room. There were some resources that I got from her at least to get my mind thinking about how you talk to a young child about something like that.

I was the one who actually decided it was important for me to talk to him myself. Both me and my husband were there, but I was the one talking to him.

All I could really do was explain that this is what has already happened with the brain tumor. Now, because of the brain tumor, they found something else.

Now, I have to have that taken out. That was a conversation. Then he knew pretty much right away that you only have 2 kidneys, so we had to talk about that.

We got his body book out, and we didn’t talk about how anatomy works. I’m not a doctor, but I know enough to explain that people can live with one kidney. It was a progressive conversation.

By the time we had the diagnosis in hand, it was a matter of adding to that by saying now that they took this out. What they’re telling me is it’s something called kidney cancer.

He seemed to have already somehow been aware of cancer — at least the word. I don’t think he has any idea of what it meant at any sophisticated level, but he know what it was.

I tried to put it into perspective, and I said, “Listen, they took it out. It’s gone. I have very good doctors who are helping me get better.”

His very first question after I said that to him — he looked me straight in the face, and he said, ‘Are you going to die?’

Of course, I don’t know why I wasn’t ready for that. I should have known. Because that’s all the kid wants to know. Really.

I said, “Listen, nobody has told me that I’m going to die. As far as I know, I’m going to be okay.” I left a bit of a hole there because he could have interpreted it more than one way, but I waited for him to see if he had more questions. I was looking for him at that point to drive more details if he wanted it.

At that point, he seemed to be satisfied with that information. We told him that we would let him know if anything changed or if he needed to have more information.

As soon as we knew what was going on, we would let him know. That was pretty much the first conversation we had with him about the diagnosis. He had just turned 7 years old.

»MORE: Parents describe how they handled cancer with their kids

Guidance for others

Everybody is different, but to receive information in the way I did, which was relatively out of the blue, was very difficult. I ended up in the ER with the problem, so I didn’t even know that there could be this issue kind of lurking.

I think that the best thing to do is to try and stay calm, as calm as you can. In those initial moments that you’re receiving this information, even the professionals around you may not have all the answers.

In fact, they usually don’t. The triage situation, this type of thing was really kind of an emergency setting, so I think to somehow recall or at least try to realize that there’s more information to come and that you will have time to decipher it on your own terms.

It’s a barrage of information initially. That information can change, and it can be nuanced. The next people you talk to, the next set of doctors you talk to, will help you put it into perspective, more than probably that first day you hear anything.

Finding the Right Doctor

How do you choose which hospital to go to?

The first hospital was not a teaching hospital. It was a community hospital. It was the one that the urgent care doc sent us to because of our insurance. We wound up there because of our insurance and because they had appointment space to do the brain MRI.

How did you choose oncologists?

In my case, because of where I was at the time of diagnosis, they were affiliated with something that was called at the time the Humphrey Cancer Center. When they sent an oncologist to my room to discuss it with us, he came from that practice.

In a way, things were happening. They were going automatically on this track. I started with that oncologist, who then orchestrated my kidney surgery.

Then he orchestrated and helped set up [and] procure the services to have the post-brain-surgery radiation that I needed. He was the oncologist who I started with because he was the one who came to my hospital bed because of what hospital I was at.

You got a second opinion

Eventually, however, within the first few months of that whole episode, I started looking for more information, partly because my husband was looking for information.

He was really gathering information about the diagnosis and about the various kinds of treatments that might be available beyond what we’d already been told.

We really just discovered that we felt like we needed more information and perhaps a different oncologist.

We went for a second opinion to the Mayo Clinic because if you live in Minnesota, you might know Mayo Clinic has a very big, well-known presence. And so we did that.

We didn’t really feel like there was much more information that we thought we would get. We really didn’t find much more information at the Mayo Clinic, so I was going to stay put with the oncologist I had already met in the hospital.

Tip: find an oncologist who specializes in your cancer

Within a few months of my diagnosis, I happened to read a book about being a cancer patient. It was called “Crazy Sexy Cancer Tips.” That was a book that my husband brought for me. Because I didn’t really want to be doing any reading or research, he thought maybe this was a book I could handle. I did and started reading it.

I came across a chapter that had bullet points, kind of like a checklist. One of the items on the checklist was, ‘Make sure that your oncologist specializes in your kind of cancer.’ I thought, ‘Wow.’ This hit me like a brick. I hadn’t asked the question.

That really led me to my next set of questions that woke me up. We started asking more questions. For this oncologist, though I liked [him] fine, it was not his specialty area.

All of a sudden, we had a mission. We found an oncologist here locally who does specialize in renal cell carcinoma, and so I switched my care to him. Then he handled my care pretty much ever since, with the exception of a few years when he moved out of state. Then he returned, so I’m still with him.

Any other tips?

Sometimes it’s hard for patients to be assertive because I feel like oftentimes we’ve learned or been socialized to feel or expect that the doctor is the person who has all the answers. They certainly have more answers than I would ever have.

I learned very quickly that being very direct and being like a collaborator in my own treatment process was a very important thing for me to be aware of. It really kind of started very quickly for me, which is still kind of in the early phase, where I went to see this third opinion doctor (whom I’m still with).

We had been asking about a particular type of treatment for kidney cancer, which is called IL-2 or high-dose interleukin-2 (HD IL-2). There were fewer options available for treatments than there are today, and IL-2 was one of them.

We had been asking questions about IL-2, because our previous 2 oncologists were like, “Well, yeah, but you can’t get it around here. You’d have to travel to find it. You’d be a great candidate for it, but you really can’t get it here.”

When we saw my third-opinion doctor for my first visit, he laid out all the imaging and everything that was going on. He said, “My first recommendation for you would be to try the IL-2.”

We said, “Great, where do we get it?” He said on the sixth floor of the University of Minnesota hospital.

That was a very early and fortuitous wake-up call, both from the standpoint that I was able to take the treatment I actually responded to, but also a real wake-up call that despite how knowledgeable professionals may be, some of them might have a blind side.

They might not be as up to date or current on the various treatments available for your particular disease or even the new developments that are coming down through the trial study process. I learned really early because of that experience, being told this particular treatment was not available to me when it actually was.

Surgery and Radiation (Gamma Knife)

Describe the prep for the kidney surgery

My kidney surgery (nephrectomy) was a couple weeks after the initial diagnosis. I lived with the fear already for a little while, and I think I was still really in a state of shock.

By the time I was in that setting to have the kidney removed, I had a very good surgeon. I was able to double-check with my own primary care doctor, “Is this a doctor that you know? Are you familiar with?” Yes.

I felt okay about where I was and who was doing surgery, which is very important. That compassionate care is a big factor in your favor if you have it.

But I was really immensely distressed. I remember the surgery went fine. There were no surprises that they found when they went in to take out the tumor and the organs, so that was good.

The result was good, but I remember being in incredible confusion about what happens next. Now what’s going to happen?

I still needed to have what’s called targeted radiation treatment to the brain tumor cavity, which is pretty standard, or at least it has been for me.

After you have a brain tumor removed, at least with renal cell carcinoma, they often and probably standardly applied high-dose radiation to the brain tumor sites to try and kill off any residual microscopic cancer cells.

I knew that was the next thing even after the kidney surgery. I had another thing to have to look forward to that I’d never heard of before.

I was really sort of still in a lot of shock and disbelief and confusion. We were really just following our instincts at that point.

All I could do was pull myself together as best as I could, because I had a 7-year-old child at home to have to try to explain things to in a way that was age appropriate for him. I would say, for me, that was probably a big part of my motivation to pull myself together.

What’s the Gamma Knife procedure?

The way they described it to me the first time is the Gamma Knife applies a high-dose radiation to a small point, but in order to get all that high-dose radiation not spread around your whole head, in my case, they have a delivery process that takes a few hours.

You go into the hospital. They do MRIs again that morning of your treatments to make sure they can plan to the appropriate levels of radiation, and then they feed it into a large, huge computer that then controls the radiation mechanism.

First, they have to put a metal frame on your head. They bolt metal frames to here with 2 bolts here and 2 bolts on the back, so you have a frame around your head.

Then they use the frame to actually bolt you into the radiation machine so you don’t move. That is something different than other kinds of radiation tools that you might hear about, which includes CyberKnife.

That, for example, is very similar, but they don’t bolt your head down. The theory is that Gamma Knife can be more precise because they bolt your head actually into the machine with that frame.

The actual radiation tool that they use — I always describe it as they put you on a bed where you’re going to lay for the radiation procedure, they bolt you into the machine, and then they back you into a “big salad bowl.”

I call it a salad bowl because they’re backing you into a dome. Inside the dome is filled with hundreds of little tiles. It looks like a mosaic. In each one of those tiles comes a low-dose-level beam of radiation.

They describe it like if you think about a bicycle wheel, it has all those spokes that lead to the center of the hub of the middle of the wheel.

If you think about what the Gamma Knife is doing, all those low-dose rays are working to focus into one place toward the delivery of the high-impact radiation. The high beam is what they’re all focusing into.

Therefore, they can deliver a much, much higher dose of radiation to a very small area and not sacrifice the brain tissue — the rest of the brain tissue that those low dose waves are going through — to get there.

Describe the Gamma Knife process in detail

The most difficult part of that process for me and probably for a lot of people is having the frame bolted to your head. The whole process requires the radiation oncologist, neurosurgeon, and a physiologist.

The neurosurgeon is there to put the frame on your head, which requires large novocaine doses to be applied to your head and into your nerves that run along the base of your skull.

That’s the least pleasant part of it. It doesn’t take very long, but that’s the first step, getting that frame bolted to your head.

I have been able to work with the nursing staff where I have this done at the University of Minnesota hospital. Unfortunately or fortunately, I’ve been able to get to know them well over the years.

For me, I get there, [and] they put me in bed. I know what’s coming now, but part of what helps me is they will give me a small amount of Ativan to control the amount of stress, if I’m having that, or a little Vicodin to manage the pain, if there is any residual from where they bolted the frame to my head.

After that, you’re really just waiting around for your turn in the Gamma Knife room. It really depends on how big the tumors they’re treating are for how long it takes.

Most of my active tumors that we’ve treated are pretty small, pea-size or a little bigger, and it can take 15 minutes of active time with the Gamma running.

While you’re laying there on the table getting the Gamma Knife, you don’t hear anything. You can hear music. You get to choose the music that pipes in. For example, you get to choose what you want to listen to.

The machine is programmed precisely based on the imaging from that morning to move. If they have to move your head, the machine does it in very tiny increments. If you’re not sleeping by then — in my case, I’m usually partially awake still — you can feel the machine moving your head a little bit to realign it for the dosage of the Gamma rays.

The longest I’ve potentially been Gamma Knifed could be maybe between 20 and 40 minutes. I’ve had 3 craniotomies, which then leaves a significant surgical site that then needs to be radiated, and that can take longer.

The tumors coming out, as well as some brain tissue. In my case, I’ve got a divot in my brain basically that needs to be radiated, and that can take a little bit longer depending on how big the site is.

Bolting the frame onto your head

It’s a whole process. The neurosurgeon is the one who does it, assisted by the nurses, who know how to do this. [It] involves a lot of careful measuring. The frame goes over your head, and they have to line it up as best they can on your head. They have to look for the best places to bolt.

(Pointing in video) This is usually where it goes in your head, right up in here. There’s 2 bolts here, and the other 2 bolts are behind in your occipital lobe, where your head or skull is dense, right below that. There’s a nerve that runs along your head right there, which is where they have to attach the other bolt.

First, they do the novocaine, which involves needles that are about 6 to 8-plus inches long in order to get through the frame. They put the frame on, line it up with where they want to put the bolts, [and] then they get the big novocaine needle to come out. It’s fast-acting novocaine.

Sometimes I’ve had 2 doctors. Sometimes they’ve done it at the same time on either side of me injecting these big novocaine needles, tirst in front. Then injecting the novocaine, it stings and burns.

It’s not very comfortable. It’s pretty painful. Then they move to the back and do the next 2. By the time they’re doing the ones in the back, the ones in the front [are] numb by now.

Then they take tools that they screw the frame into your head. They’ve got tools and bolts that they then actually screw into your skull at that point. They literally get out their wrenches and are wrenching it into your head. You can hear the metal; you can hear them wrenching. By that time, if they’ve done it well, you can’t feel it anymore.

Advice on dealing with Gamma Knife

I’ve had it done so many times, I know what to expect. If you’ve never been through it before, the one thing I say is it goes really fast. It’ll be over very quickly. If you can use whatever techniques you may already have or be aware of, if you can breathe through the bolting process to get through it, it doesn’t take very long.

What I do is fixate and look at something ahead of me. I don’t close my eyes. It doesn’t help me, but for some people it might because they wouldn’t see the needle. I focus on something else, and I can pretty much count on a minute or less of that intensity of the bolting process. It does subside. Once it’s done, you’re waiting to get put into the Gamma Knife tube, and you can sleep.

Then you can go home. They bandage up your head because they want you to keep those bolt sites clean. Then I usually go out to breakfast with a big bandage on my head to my favorite pancake place.

You may not really remember all of it once you nap it off, so that’s the best thing I can say. It will go fast. It will be done. In this case, the results of the Gamma Knife on this type of cancer is pretty effective.

Treatment Decisions

How to deal with recurring brain tumors

After the original surgeries that I had — the first brain surgery, kidney surgery — and first year I was diagnosed, I also ended up having a lung surgery. That lung surgery was to address a couple of lung mets that were later discovered that were not behaving. Everything else systemically seemed to be behaving. These 2 lung mets weren’t.

The idea was to go in, remove those lung mets, and they won’t be there anymore. I had these 3 surgeries in a short period of time, plus the IL-2, plus the Gamma Knife, all within that first year.

What I didn’t realize was that for me, the most of my recurrences with this disease have been brain tumors, which meant that I was getting scanned (MRIs, brain scans) every 3 months.

In that first year, the first couple of years, I was having serial brain tumors. Pretty much every 3 or 4 months, I’d have another brain tumor, so I’d need more craniotomies as a result of those tumors when they didn’t respond well to the Gamma Knife control.

I’ve had 15 brain tumors in close to 10 years. You can see how often they’d come. I had one period when I did not have any brain tumors for about 2 years. Currently, I have not had a brain tumor for a year and a half.

Importance of constant MRI checks

Originally, when I was diagnosed, because of the brain tumor situation, the radiation oncologist, who I had been seeing ever since then, pretty much said don’t let anybody tell you to wait longer than 3 months between brain MRIs. That was a recommendation that I had tried to live by.

The point is, if they find something when it’s still small, it’s much easier to treat.

That path has deviated at least once for me, which didn’t turn out very well. This is another area, as a patient, I’ve had to learn even if the neurosurgeon says it’s okay to wait 4 to 5 months and the other doctor says it’s not, you, as a patient, have to make sense of that.

In my case, I learned the hard way. I am now very committed to not waiting more than 3 months between brain MRIs.

As you go through your cancer process, depending on how long it takes to get it under control, or maybe you’re constantly managing it like in my case. This is a situation where one of the doctors that was monitoring me actually missed on. He didn’t see it. It’s happened to me more than once.

These tools they’re using, they’re not perfect – they’re good. It’s better to have imaging than no imaging, but they’re not perfect, not infallible. That’s true with any doctor, as well. As good as they may be, they’re still human beings so there may be a margin of error.

I’ve had a couple of cases when I had a couple of brain tumors that weren’t picked up when they could have been, which gave them time to get bigger.

Hopefully by having frequent MRIs like that, the potential for a brain tumor to get out of control is reduced, but it’s not zero, in my case, at least. Once a brain tumor gets to a point, it shouldn’t be in your brain anyway, so the chances for a brain tumor to cause problems cognitively or with swelling is always there.

Once they apply a radiation tool, the brain will also swell in reaction to the tissue damage so there’s constant monitoring anyway of what the side effects might be, even with having a Gamma knife.

If I’m having them done regularly at the three-month point, they can treat it when it’s smaller. When it’s smaller, you reduce the possibilities for a brand new adverse outcome.

How to talk about different treatments with your doctor

My husband did the early heavy lifting. I was pretty out of commission in terms of that thought process. He was able to do that originally. The oncologist I have now is a researcher as well as a clinician, so he’s very knowledgeable about the types of new and coming, ongoing research when it comes to treating this kind of cancer.

Since I’ve been with him since the beginning, the dialogue has grown. It’s grown as we have become more knowledgeable.

For me, because kidney cancer back in 2011 when I was diagnosed happened to be a type of cancer that was known to potentially respond well to immunotherapy.

Immunotherapy at the time was still a relatively dubious treatment because it had not been very fruitful for many, many years from a research standpoint.

However, my oncologist was very aware of the research and the trials that were underway at the time, where they were having some new success with immunotherapy products.

He was really instrumental in helping us understand the vocabulary, the types of drugs that were being studied, what they did, how they operated, and how the use of these new and coming drugs would be deployed for me, as needed.

There was a strategy from the beginning around which things to use first and which things to reserve. The doctor had a way of talking about it that helped us understand.

- We’re talking about what’s our toolkit to fight this?

- What kind of things do we take out first?

- What things do we take out later?

- What kind of things might interfere with each other?

We’ve learned a lot as we’ve gone. We’ve also taken it upon ourselves to follow the research as it is actually developing.

So we’ve come to the point where we can follow some of the science at a layperson’s level, but comes to life for me because I’ve lived it.

»MORE: Read more patient experiences with immunotherapy

No standard of care

I think it helps if you have an ongoing curious mind. There’s more than one way to look at the problem.

Sometimes finding more than one way takes a little longer. Sometimes people feel very rushed and pressured to make a treatment decision right away. Sometimes, that’s necessary. I can’t speak for every situation.

But I think probably more often than we realize, as a patient, you should be able to have adequate time to really try to understand what’s on your plate, what might be missing from your plate, and if you need to go gather more information to find a way to do that.

A potentially good question to ask yourself is does this doctor specialize in my particular kind of cancer? And in my case, it was no.

I had to go further. Something we don’t know when we start this process is not every doctor is going to have the answer and maybe it’ll be a team of doctors that work together to formulate the answer. It may not be clear to you in the beginning but I don’t think it’s ever a bad idea to give yourself some time to think through what’s going on.

Figure out the questions that you want to ask. Find another source of information. It could be looking on the internet, looking for a particular disease type, looking for doctors or institutions that specialize in a particular diagnosis that you may end up with, and ask a lot of questions.

Ask a lot of questions

That’s the best thing I think any patient can do is to ask a lot of questions. If a doctor doesn’t like it, which I’ve had, then I think that’s also something as a patient that you should be able to call the shots on. It isn’t necessarily easy.

Taking care of your mental health

The other thing is your mental health as a cancer patient, somebody who’s been diagnosed with cancer, is very crucial to take care of.

I can speak for myself where I went through at least the first two years with my diagnosis being pretty depressed.

I would have antidepressants offered to me, counseling therapy offered- my initial reaction was why? It’s appropriate for me with stage 4 cancer.

I can only say how wrong I was. Once I was able to recognize that having my mental health in as good a position as I could would only bolster what I could bring to the table for my own understanding and my own path for treatment decision-making.

Dealing with another recurrence

Part of the way I dealt with it was a function of what I’d already been through, including the two years of still period. I was still getting regularly scanned, with scans come a lot of anxiety and uncertainty.

By the time I had the recurrence, I’d had several years of dealing with what they call “scanxiety” and dealing with the uncertainty, and in many cases, that uncertainty was unbearable.

You learn how to cope with that, hopefully, in the best way you can. Even though I’d had a couple of years without any brain tumors and without any visible disease from the imaging, in my case, I had already learned that some of these imaging was infallible – not always as accurate as you might hope it is. So I kind of always knew tat day would come. It’s part of the paranoia you live with as a cancer patient.

When it happens, it was like going back into autopilot – back into gathering information, understanding mode, the lessons we’d already learned so far were part of what we dealt with with this new situation, which included follow-up testing.

We needed more testing, the original wasn’t enough. We needed to talk to more than one doctor. By then my original doctor had returned to Minneapolis so I reached out to multiple specialists to get more opinions.

I will say, once again, the original reaction to what to do in the case of the recurrence in my remaining [kidney] was surgery. Let’s go in and get it out! I thought I’m not sure I like that idea because I only have one kidney left.

Getting yet another opinion which was a return to my oncologist who’d just come back to town, which was fortunate, and the answer he gave was different. It was I think we should not do surgery right away. If we have to do surgery, okay, but even if that’s the case, you only have one kidney left. Even in the best situation, surgery can go wrong.

So that was again, we deployed our process which we’d been learning all along which was to ask many, many questions, figure out what options are available, and make the best choice I could at the time.

It was by then, we had learned many lessons to deploy which was chiefly, gather the information, make sure you understand what you’re seeing, look at the records and reports, read them, ask questions, don’t necessarily go with the first recommendation until you understand – in our case – what the variables were.

Immunotherapy

Trying immunotherapy

This was really the first instance where I’d had spread of the disease discovered in my other organs other than my lungs and kidney, left one which was now gone. This was a new frontier for me being that it wasn’t my brain this time.

So what we tried first was body radiation, which is like Gamma Knife to the body. It’s not necessarily as effective but it’s a potential option. That’s what we tried first, to see if we could contain the kidney tumor with radiation.

It didn’t work and so the next step was to try two things. The next thing we tried, we knew we wanted to get my onto the nivolumab which is also known as Opdivo, a type of immunotherapy. However, the kidney tumor at the time was big enough that it was starting to encroach on one of my ureters.

There was a need to shrink that tumor if we could, as quickly as we could, before putting me on the nivolumab, the immunotherapy, because the immunotherapy doesn’t necessarily work that fast.

What that meant was I had access to two drugs that had recently been approved by the FDA, within a handful of months, before I needed them.

I started taking something called cobimetinib which is another type of immunotherapy, a different kind of a drug. It operates to cut off the blood supply to that tumor.

The idea was to keep me on that as long as I could so I could get the multi benefits out of that particular treatment, then switch me to the nivolumab (Opdivo) for longer-term maintenance. That’s exactly what I did.

I was on the cobimetinib approved months before I used it and I was on it for less than a month before the side effects got me kicked off of it, because they were going to have some harsh side effects.

What are the cobimetinib side effects

Because it was a recently released drug, the dosage was still high. So I was on what would have been considered a very full dose at the time for me. One of the first things that happens is you get high blood pressure, so I was on high blood pressure medication. That can be manageable.

The thing that ended up tainting my experience the first time involved uncontrolled diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting. When you can’t control those three things and significant GI symptoms that were not able to be controlled by other kinds of medications so I was on that particular drug for less than a month before the decision was made to get me off of it and put me on the nivolumab.

Nivolumab immunotherapy

That was a decision we made. But even after being on that cobimetinib for less than a month, the kidney tumor had already shrunk significantly so it was no longer encroaching on my ureter or causing any more problems like that.

So I went onto the nivolumab, it was a one-two punch. The nivolumab I was on for about eight months in different courses. First it was once every two weeks, then once a month, then once every five weeks, but after about eight months of constant monitoring, all the visible cancer they had seen in my abdominal cavity, including the kidney tumor, were gone.

The nivolumab had also been a really recently released drug so to be able to take those was like just-in-time medications.

Nivolumab side effects

For me I haven’t really had a lot of side effects.The only thing I’ve experienced which is pretty unique but it can happen is I’ve had hives. I go to the cancer center to have the nivolumab infused. They set me up with an IV and it took about a half-hour.

After I’ve been on it for many, many cycles, I started to get a stray hive here or there. I got one on my neck. But it happened two or three times. Of course the concern is, with immunotherapy, there’s potential to cause an overreaction in the immune system.

Hives and anaphylaxis, another degree reaction, could be very serious. They would treat me in the chair when those hives showed up with intravenous Benadryl, so I would get kind of sleepy with the IV Benadryl. That happened two or three times.

Now what they do is pre-treat me with oral Benadryl. I get there, get IV hooked up, they do blood tests, monitoring, then give me the oral Benadryl to kick in for 20 minutes. Sometimes by then, my medicine’s there and they hang it up. So for me, that’s been the only side effect I’ve had which is very manageable.

How do you get access to immunotherapy

My current oncologist, who I’d had throughout all of my significant treatment, has the prescribing authority. He’s very knowledgeable about all of these drugs which again, goes to one of my earlier points which was know who your doctor is and what they know how to do.

This particular oncologist has such a deep knowledge of clinical, not only in the clinic, but the trial studies. He’s been the head of more than one clinical trial program so he’s very knowledgeable and has farflung professional contacts that help inform him.

He’s deeply involved in that side of the practice so he’s very knowledgeable. When it came to understanding these options, it was not only him helping us understand the treatments, what these various treatments would do, but access to them.

I’ve also had very good medical insurance, health insurance ,and never really encountered a problem with either rejecting or extraordinarily high costs with my healthcare, at this point.

I know that could always change, there’s always some uncertainty to some degree where our health insurance is headed. That’s another significant component, has been my very stable and available health insurance. I’ve never had a problem with it.

I know for people who are unable to get coverage or the co-pay is too expensive. These pharmaceutical companies apparently have programs that help patients pay for their treatment. I’ve never had to invoke that but there have been times where that was put on the table.

Quality of Life

Advice on ongoing treatment advice

Outside of the fundamental hope that a patient can find the right oncologist or oncologists team approach, being able to and willing to do your own due diligence and participate actively in the treatment decisions so that you can be as intolerant as possible with what’s happening to you.

What me and my husband have really learned over the years is for me in my treatment, it’s really been ongoing, with a couple of breaks, but we pretty early on realized that this was not a cancer that was going to go into remission exactly.

Making the series of treatment options and decisions has really been on the emotional side, which is critical to be aware of, as much as it’s hard and it’s like running a marathon in a lot of ways, to continue this kind of lifestyle.

Every new situation that requires some kind of intervention, whether it’s a new brain tumor or recurring mets somewhere else, something we thought was put to bed then it comes back, what we have strived to be able to say to ourselves is well, let’s see what we do next. What do we do now? Let’s marshal our evidence and resources and take the next step.

Did you stop working

I was in a form of denial. I kept working. My capacity was not affected at all from the standpoint of my mental capacities. I worked from home for a little while after I recovered from the surgeries and went back to work.

For me, work was a good way to distract what was going on and to maintain the normalcy, so I was very fortunate to be able to do that.

And at the time, I had some very supportive co-workers and a supportive workplace. So that was, I think an example of how I dealt with it through trying my best to deny that it was really affecting me.

I changed jobs a couple times after that and eventually, for a variety of reasons, I ended up sort of on my own. I established my own practice almost two years ago.

It was in that process and that timeframe that I had an episode of brain tumor. I’ve had many, many brain tumors at this point, which are treated either by radiation or brain surgery. I’ve had three full craniotomies to remove brain tumors, about 15 brain tumors all together by now.

When they’re small enough, they will treat them. If it’s a small enough tumor at least with kidney cancer, they used, for me, the Gamma Knife which is a high dose radiation tool.

»MORE: Patients talk about working during cancer treatment

Dealing with uncertainty and mortality

Whenever there’s a potential mortality staring you in the face, it does sharpen your view of the present. For a long time, that was all I could hang onto, was the day.

I had a hard time looking too far ahead in my calendar and scheduling appointments but at some point, there’s a balance. There’s a balance for us that everybody has mortality, there’s a clock on everyone, that’s just the way it works. We just know mine is ticking really loud.

It becomes more of a balance. Remembering that we’re here today. Tomorrow is never guaranteed for anybody and what do you want to make of that? How does your experience help you actually see life in a different way?

I’ve been dealing with this for almost 10 years. My child had just turned seven on the day of my first brain surgery. He is now 16 going on 17, and we’re teaching him how to drive!

We’re stuck inside with COVID-19, and so I think the takeaway in some ways is to try and find a balance, because nobody can predict what’s going to happen to you. Nobody.

The statistics may tell you one thing. I can tell you when I was first diagnosed, I gave every doctor who walked into the room to meet with me an advisory, I don’t want to hear any statistics, because I knew they weren’t good. They were not good. They were single digits for me to be alive in five years. I knew they couldn’t be good. But that was how I controlled it.

I didn’t want to be reduced to a statistic. I think there’s something very empowering about that that people can think for themselves, that nobody knows what your path is going to be. I’m a really, really good example of that.

Nobody expected me to still be alive today. Except maybe my husband! But there’s a really important message there to me – no matter, really, what somebody tells you is going to happen to you, nobody really knows. And you can hang onto that in a positive way.

And you can look forward, stay present, and look backwards sometimes. In life, looking backwards has had the benefit of helping others, so I think that’s a very valuable thing to bring to the table for yourself.

Describe dealing with scanxiety

That was a process. I think people develop their own strategies. Everybody’s different. I, for whatever reason, have been able to compartmentalize it.

It wasn’t that way at first because the upcoming scan would always mean another opportunity to find more disease, which of course is the scanxiety part of it.

For me, with time, I just learned over the course of extraordinarily painful experiences that I had to be able to coexist with some of these almost unimaginable kinds of frightening things out there that I couldn’t control.

So in my case, I just learned to compartmentalize it because it was almost impossible to exist on a day to day basis if I was worried about the next scan all the time.

What that means is by now, I don’t really get scanxiety anymore. I will get most anxious waiting for the doctor to come into the room to tell me what the results are. So I’ve reduced the timeline to sitting in the waiting room and that’s what works for me.

I know my husband has a very different experience because he’s a different person and he’s also not the patient. He’s got a very different perspective, so he still struggles with the scanxiety.

We just have very different ways of coping, but for me, that was it. I had to make a proactive decision that it was too difficult for me to live in that emotional upset on a continuing basis. I had to flip the switch for my brain.

»MORE: Patients describe dealing with scanxiety and waiting for results

Message to other patients

Finding it somewhere inside of you to get back up everyday, do something. You can put one foot in front of the other even if you’re still recovering from surgery or something.

Find whatever that is, that place within you that allows you to pick up your head and face the next day. That’s kind of a big thing, but it’s an important thing. That’s what I’ve learned.

Inspired by Laura’s Story?

Share your story, too!

Kidney Cancer, Renal Cell Carcinoma Stories

Mia H., Kidney Cancer (SMARCB1-Deficient Renal Cell Carcinoma, Non-Sickle Cell Trait), Stage 4

Symptoms: Bad cough, fatigue, nausea

Treatments: Chemotherapy, radiation, immunotherapy

...

Alexa D., Kidney Cancer, Stage 1B

Symptoms: Blood in the urine; lower abdominal pain, cramping, back pain on the right side

Treatment: Surgery (radical right nephrectomy)

...

Bill P., Papillary Renal Cell Carcinoma, Stage 3, Type 1

Symptoms: Kidney stone, lower back pain, sore/stiff leg, deep vein thrombosis (DVT) blood clot

Treatment: Nephrectomy (surgical removal of kidney and ureter)

...

Burt R., Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumor (pNET) & Kidney Cancer

Symptom: None; found the cancers during CAT scans for internal bleeding due to ulcers

Treatments: Chemotherapy (capecitabine + temozolomide), surgery (distal pancreatectomy, to be scheduled)

...

Sonia B., Kidney Cancer, Stage 1

Symptoms: Fatigue, abdominal discomfort, flank pain, constantly abnormal bloodwork

Treatment: Surgery (partial nephrectomy, ileostomy)

...

8 replies on “Laura’s Stage 4 Renal Cell Carcinoma Kidney Cancer Story”

Thank you Laura for sharing your journey and advice on how to navigate through stage 4 kidney cancer. I have had one kidney removed and now have nodes in my lungs, receiving targeted therapy in the form of Sunitinib tablets. Prognosis is 6 months to two years and a five year survival of 8%. Your story has given me new hope and confirmed my approach of asking many many questions about my treatment which in the UK can be influenced heavily by cost as we are under the National Health Service. I have a scan this week and a meeting with my oncologist, with whom I will be entering into straight talking conversations about what’ treatments are available to me and why they are either being recommended or not. Immunotherapy seems the way forward to me after reading this, so this will feature in discussions. You have given me so much information and most importantly hope , God bless you

Thank you so much for your story. My sister Christina was recently diagnosed with RCC stage 4. She will start her regimen of medication in 2-3 weeks. Your story has given her hope and that she has a chance for success. If you or any of your followers have information about to handle the side effects, please share.

Laura, I loved your story. It has really helped. I was diagnosed with stage 3 kidney cancer in my right kidney April of 2020. Just as Covid hit. It was removed along with the adrenal gland and 3 lymph nodes. One year later it showed up on my right kidney. Small tumor was removed. Six months after that the kidney cancer spread to my only adrenal gland. That was recently removed. Now I deal with artificial hormone replacement each day. I will begin Immunotherapy in a month. It’s been a long 2 years with many to come. Your story, as well all of the stories have helped me a lot. Thank you. It’s good to know you are not alone.

Wow! I was recently diagnosed with renal stage 4 and told that there was pretty much nothing they could do except prolong life or at least try. They said that removing the tumor was not an option. This was helpful. Thank you for sharing.

Hi Michelle, How are you doing? My husband was diagnosed stage 4 in March 2022. He started Keytruda and Lenvima combo the beginning of April. We were told it was not operable as well. However, if it started to shrink out of the renal vena cava, it could be surgically removed. He had mets to the liver, lungs, lymph nodes, and one rib/vertebrae (respectively). His 3 month scan was two weeks ago with great results. The kidney and liver tumors had shrunk by 1//4 each and all other areas remained stable with no increase. The area in the renal vena cava was 17mm in March, as of the 3 month scan, it has shrunk to 9mm.

So generous in content, intellect and spirit. THANK YOU for the privilege of listening, while reading. The wonderful pictures enhanced the VERY helpful experience.

Jan, thank you so much for your kind words. We’re so glad Laura’s story was helpful!

Thank you, Stephanie, for this insightful interview. Was just diagnosed with stage 4 RCC, with liver mets. I have a strong faith, and these personal stories help guide me and encourage me. So from the bottom of my heart, thank you! Thank you for asking the hard questions, in regards to sharing news with kiddos; finances; insurance; keep asking questions to be able to know all the options. Your interview really helped me!!