Blood Cancer Treatment

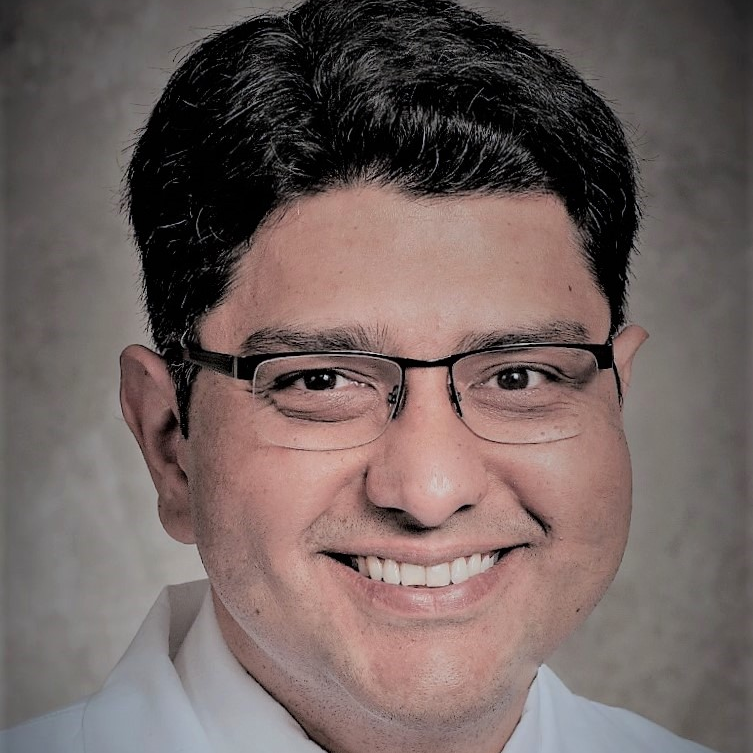

A Conversation with Dr. Farrukh Awan

Dr. Farrukh Awan, a blood cancer specialist who treats people diagnosed with leukemia and lymphoma, shares his work background and the overall picture of progress in blood cancer treatment.

Dr. Awan, an associate professor and hematologist-oncologist at UT Southwestern, is a member of several professional organizations, including the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and the American Society of Hematology (ASH). He is also the recipient of the Young Investigator Award from ASCO and has published on many topics, including ibrutinib and acalabrutinib.

What are you most passionate about in your work?

I’ve always been interested in studying leukemias and lymphomas, studying the cancer biology:

- How does the cancer become resistant?

- What can we do to overcome that?

- How can we eliminate the cancer cells and basically, effectively cure our patients?

Developing new drugs is part of that, being a part of those efforts, trying new drugs, combining it with one or the other options that we have already available, studying the side effects, managing the side effects.

I think those are the things that I feel are important, and in my small way, I can impact the field and slowly move the field forward.

That will happen one patient at a time. The idea is to help as many people as we can

Multitude of blood cancer subtypes

I’m primarily a leukemia doctor and a lymphoma doctor. I basically focus on lymph node cancers. If there is a leukemic version of the lymph node cancers, those are my areas of expertise.

I can tell you that there’s 80 different types of cancer in that group. At least 80, maybe more. Within those 80 diagnoses, there are more subtypes in those groups. It’s not one cancer. That’s the first thing to remember. It’s a family of cancers.

Every cancer has a different name, every cancer has a different subtype, every subtype is treated differently, is managed differently. Just saying that you have lymphoma narrows the diagnosis down to maybe 80 different options.

Even if you say a non-Hodgkin lymphoma, that narrows it down to 75 different options.

It really is a very, very complicated, very broad field. We have a lot of patients who get these cancers, but fortunately, it’s not as common as breast cancer, lung cancer. Those are more common than lymphoma.

We don’t have as many patients as the more common cancers but we still have a fair number of patients who are living afterwards, after they’ve been cured, after they’ve been treated, or in remission.

We have a lot of people who’ve been exposed to this cancer, who are dealing with this cancer, and are survivors of this cancer. We have a fair number of those patients.

What’s the progress of treatments in lymphoma and leukemia?

Just within the lymphoma field, there has been a significant increase in the number of new drugs that have been approved over the last few years. Even in the last two or three years, it’s at least five or six new drugs.

Then it also depends on what subtype you’re looking at. If you’re looking at large cell lymphoma, there’s a whole slew of drugs that are approved for that.

If you’re looking at the second-line, third-line treatment, fourth-line treatment, there are drugs in every spot which were approved. Then if you’re looking at follicular lymphoma, there are drugs approved for that. If you’re looking at marginal zone lymphoma, and so on and so forth. If you’re looking at CLL, there are so many new options.

The point is that if you look at the whole lymphoma family as a whole, there would be probably 15 or 20 new drugs.

If you look at the individual subsets, every subset has some new option, or multiple new options in the last few years, which is really impacting the outcome of our patients. It’s getting better and better every day.

New treatments = new choices + less certainty

Patients have more choices now, which also basically puts us in a tricky spot as physicians because now sequencing becomes a big question mark.

- Which one should we do first?

- Which one should we do second?

- What are the pros?

- What are the cons?

- Which is curative?

- Which is not?

As our options are increasing, our ability to give it to our patients is also improving, but it also makes it more nebulous, because we don’t know what the right sequence is. Nobody does. It’s a lot of opinion. It’s a lot of early data.

This is exactly why we need clinical trials because that’s the only way we can answer what is the right sequence of events. How should we do this so we can eventually cure everyone without having to use chemotherapy ever again?