Advancements in Metastatic Breast Cancer Treatment & What They Mean for You

Abigail Johnston was a successful lawyer and mother of two young children, living a fulfilling life before being diagnosed with stage 4 metastatic breast cancer in 2017. Her diagnosis, with a prognosis of just 12 to 36 months, was devastating, but she chose to take an aggressive approach to treatment.

Abigail shares the emotional toll of her diagnosis, how she focused on being present with her family by closing down her law practice, and then highlights the power of how understanding more about her disease would change her life, specifically in understanding her cancer biomarkers.

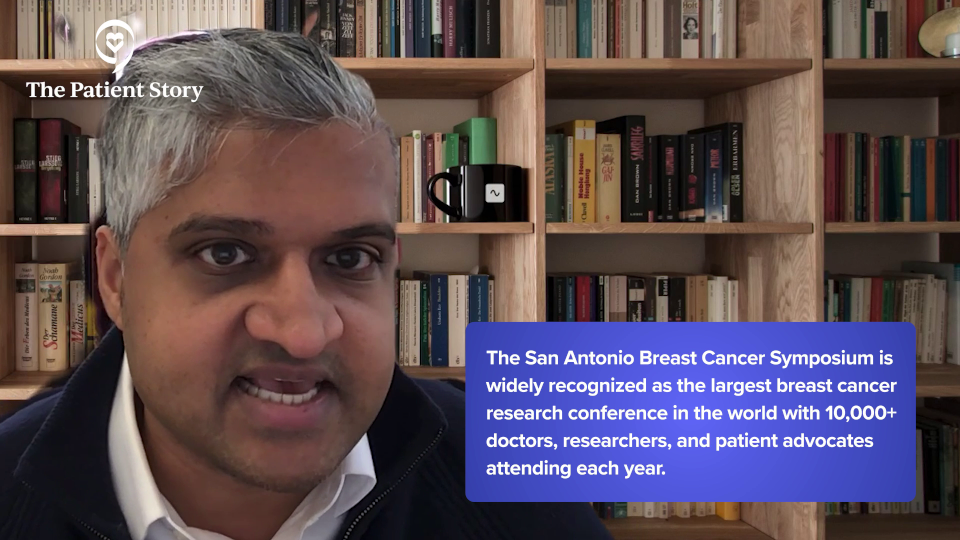

As she reflects on the incredible advancements in metastatic breast cancer treatments and the hope she holds for long-term survival, she brings in another top expert voice, breast cancer specialist, Dr. Neil Vasan from Columbia University, to discuss the latest updates from the largest breast cancer meeting in the world, San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

They talk about the most promising treatments that may be close to FDA approval, how getting tests to understand your disease can completely change your life, and even how the weight loss drugs like GLP-1s have entered the conversation in breast cancer.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider to make treatment decisions.

Edited by: Katrina Villareal & Stephanie Chuang

- Introduction

- INAVO120 Clinical Trial

- EMBER-3 Clinical Trial

- PATINA Clinical Trial

- The Impact of Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADCs)

- Improving How to Get Medicine to People

- Addressing Obesity in the Context of Breast Cancer

- The Importance of Understanding Side Effects

- The Importance of Sharing Side Effects with Your Doctor

- What are You Most Excited About in Breast Cancer Research & Development?

- The PIK3CA Pathbreakers Patient Advocacy Group

- What’s Exciting About Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS)?

- What are Your Recommended Patient Resources?

- Conclusion

Some live for 15, 20, and even 25 years with stage 4 metastatic breast cancer.

Introduction

Abigail Johnston: I have been living with stage 4 metastatic breast cancer. At the age of 38, I was told I had 12 to 36 months to live. As a young person in the middle of my career with two young children, hearing that was devastating and overwhelming.

I chose to be more aggressive and have my treatments happen in a certain way because I’m always thinking of being present with them. I closed my law practice about a week after my diagnosis because if I was going to have limited time, I wanted to spend all that time possible with my kids and not in the office. I count those times with my kids and my husband as so much more valuable.

Some live for 15, 20, and even 25 years with stage 4 metastatic breast cancer. We need to understand why they live for a very long time. Is it a particular medicine? Is it a particular biomarker? Is it something about their genetics? That’s where precision medicine comes in.

Dr. Neil Vasan: Breast cancer is multiple diseases. It can be estrogen receptor-positive, triple-negative, and HER2-positive. This discussion is for women and patients with metastatic breast cancer, but of course, we have a lot of advancements happening in the curative breast cancer setting.

We think about screening and genetic mutations, and the advances there, which straddle all types of breast cancer. Especially for this audience, three important trials were either initially presented or updates were presented at the 2024 San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

Editor’s Note: Clinical trials can seem complicated or technical, but there are later-stage trials that may be a great option for patients, not a “last resort.” See our video/article focused on “What is a Clinical Trial?”

According to the National Cancer Institute: “Clinical trials test new ways to find, prevent, and treat cancer. They also help doctors improve the quality of life for people with cancer by testing ways to manage the side effects of cancer and its treatment.”

For a lot of metastatic trials in the past, we have used tissue biopsy, which is obviously more invasive and takes time to analyze. This trial utilized liquid biopsies in approximately 93% of patients, which was remarkably high. It also enabled this trial to report results quickly.

Dr. Vasan

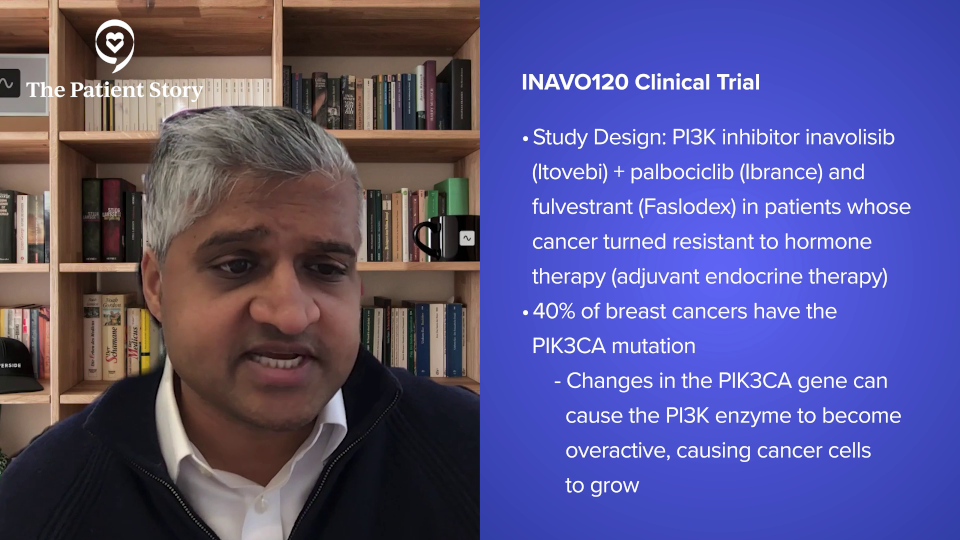

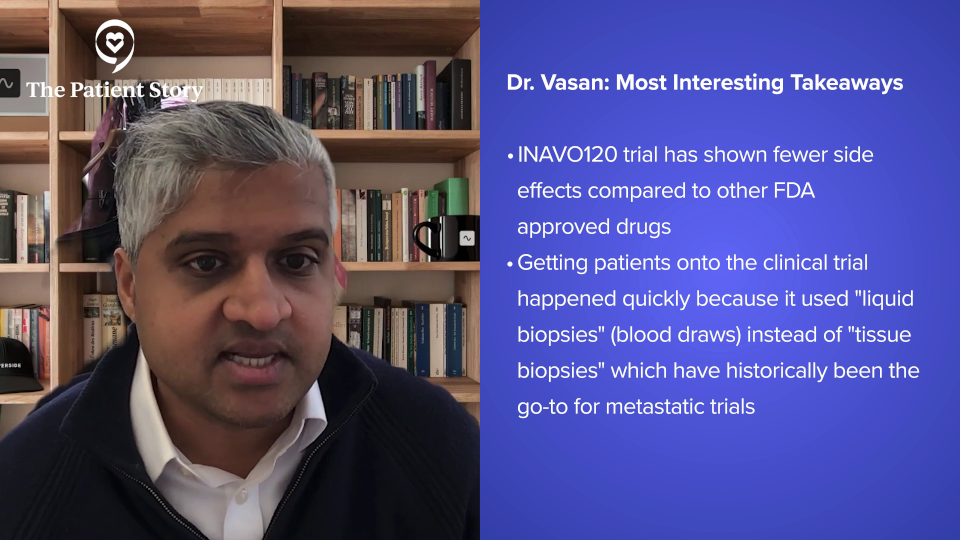

INAVO120 Clinical Trial

Dr. Vasan: The first clinical trial is INAVO120, which is a trial testing PI3 kinase inhibitors in the first-line setting in women who have progressed on adjuvant endocrine therapy. Thankfully, this is very rare, but we do see it. We do know that there are women who only get one or two years of mileage out of these therapies. Sometimes, these therapies can just stop working. This is a hard discussion with patients because the therapies that we think are supposed to cure you didn’t work.

This was a trial that looked at a type of drug that we give in the later line setting of breast cancer. This is called a PI3 kinase inhibitor. This is based on the fact that 40% of breast cancers have mutations in PIK3CA, which is the main engine of this pathway.

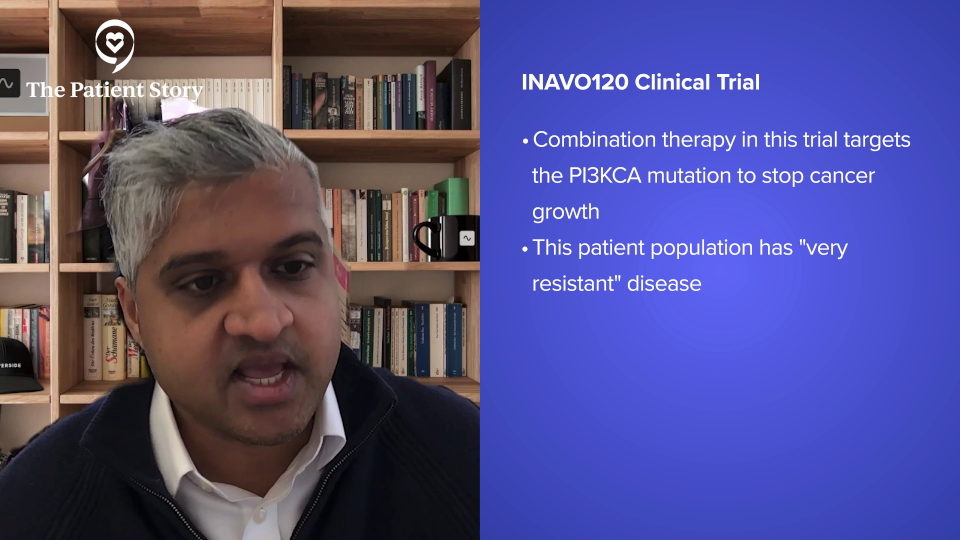

What was interesting about this trial was that they investigated this drug in combination with palbociclib, a CDK4 and CDK6 inhibitor, and fulvestrant in women who had either progressed on adjuvant endocrine therapy or progressed one year with infection. This patient population has very resistant disease.

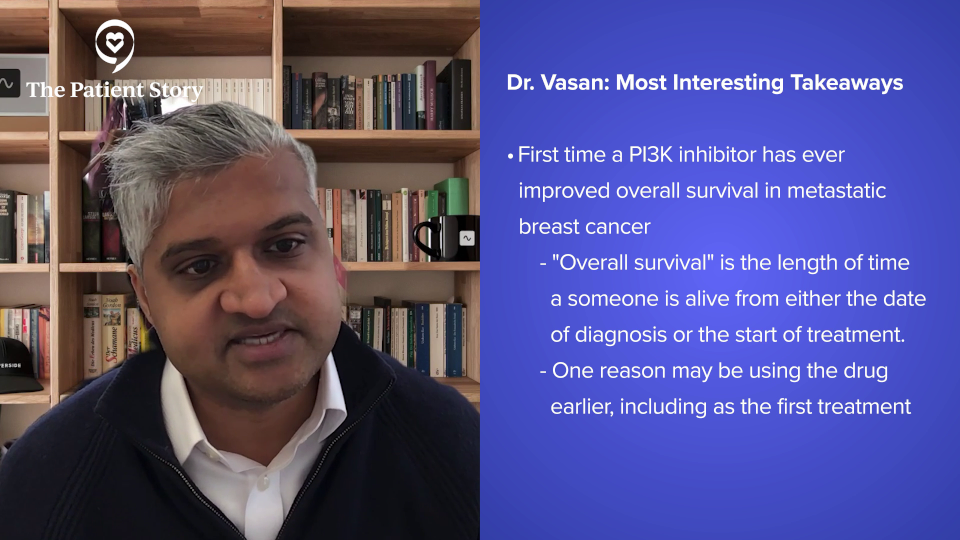

There are a couple of interesting things about this trial. When this trial was initially reported, it doubled progression-free survival. Very recently, we had a press release stating that it improved overall survival. We don’t yet know the numbers for the overall survival improvement, but this is a significant achievement in the field. It’s the first time for a PI3 kinase pathway inhibitor to have improved overall survival in metastatic breast cancer, so that is a huge deal.

We’ve had drugs like everolimus that have targeted this pathway for decades, but we’re only now starting to see the fruits of that. The reason why overall survival has improved is because of a combination of factors. First of all, we’re using this drug in the first-line setting, so we’re putting all the weapons in one go in trying to eradicate breast cancer.

Second, we, as a field, have made a lot of progress in monitoring toxicities and making sure that these therapies have manageable toxicities. That was another important part of this trial. It was a drug that’s better tolerated than alpelisib, which is FDA-approved.

Lastly, this trial enrolled quite quickly because it used liquid biopsies. For a lot of metastatic trials in the past, we have used tissue biopsy, which is obviously more invasive and takes time to analyze. This trial utilized liquid biopsies in approximately 93% of patients, which was remarkably high. It also enabled this trial to report results quickly.

Some of the things I’ve mentioned have to do with the science, but some of them have to do with implementation issues and toxicities, which are science as well, but in a different way. All of these variables matter. This trial is practice-changing and I’m looking forward to hearing about the overall survival data.

Editor’s Note: This interview has been edited for clarity and length. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider to make treatment decisions.

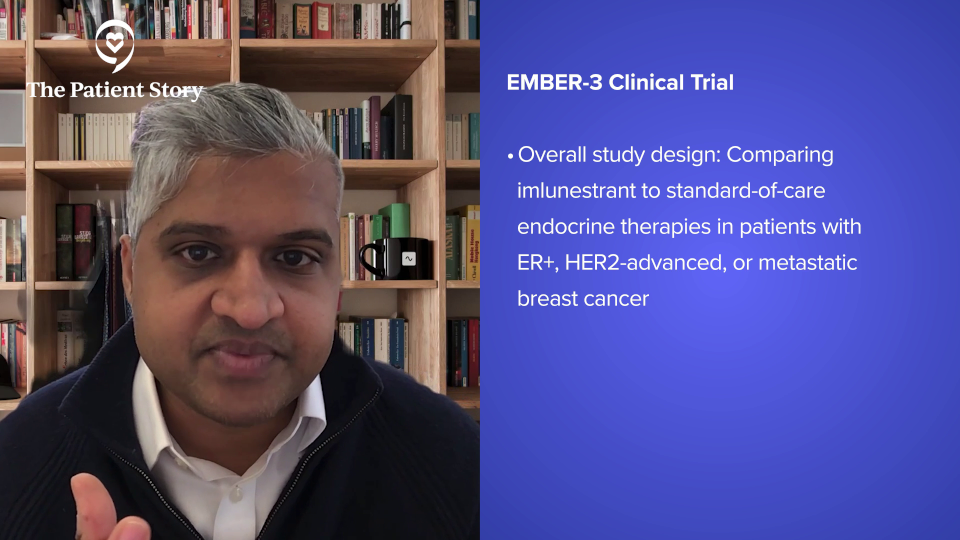

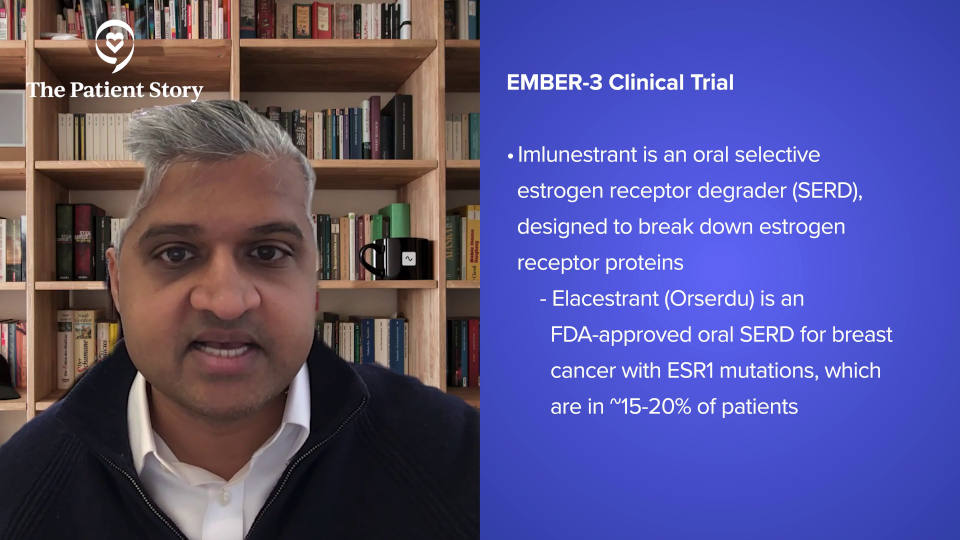

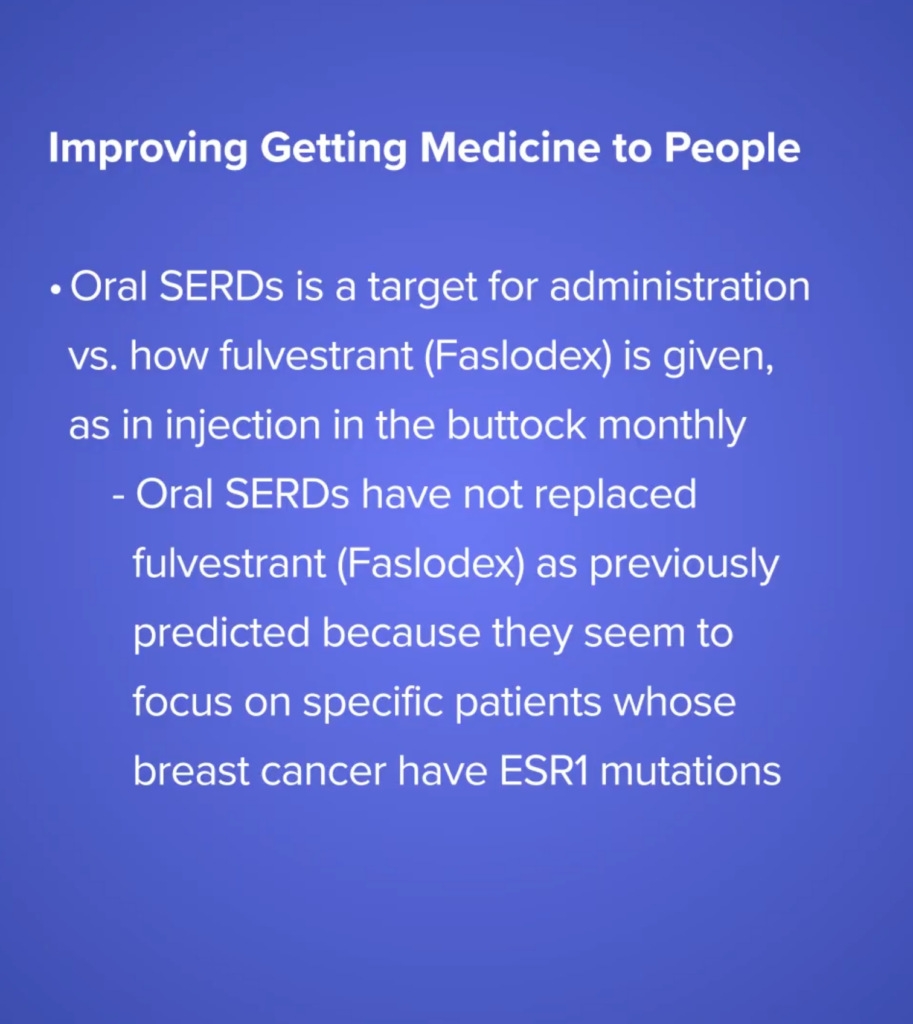

EMBER-3 Clinical Trial

Dr. Vasan: The second trial was looking at a drug called an oral selective estrogen receptor degrader (SERD). The EMBER-3 trial was investigating a drug called imlunestrant, which is sort of an oral version of fulvestrant that degrades the estrogen receptor. There’s already an FDA-approved drug called elacestrant, which is for women whose breast cancers have mutations in the estrogen receptor or in a gene called ESR1.

We see these mutations in about 15 to 20% of patients. I would say that number is a little bit all over the place if you look at the literature. We know that this mutation arises because it is a drug-resistant mutation to aromatase inhibitors. Women whose breast cancers progressed on adjuvant aromatase inhibitors often can get this mutation.

Imlunestrant was tested in combination with abemaciclib or a CDK4/6 inhibitor. This was a trial that looked at a complicated trial, but the gist is that in women whose breast cancers harbored an ESR1 mutation, those women had a longer progression-free survival if they took imlunestrant versus an endocrine therapy of their physician’s choice, which might be fulvestrant or an aromatase inhibitor monotherapy.

There were other more complicated arms of the trial where they looked at the combination of imlunestrant and abemaciclib in patients who had progressed on CDK4/6 inhibitors in the second line. Those resulted in positive data. They had improved progression-free survival. I’m not going to delve into the details of that because, honestly — and I say this as a breast oncologist — it’s challenging to understand exactly. The comparator arms were not necessarily what we would use in the second-line setting.

For any average patient in the second-line setting, we would obtain their genomics, figure out the exact targeted therapy, and then give them that therapy. This trial did not test that particular question. It showed that this combination has efficacy, but it’s hard to understand who the right patient population is. I look forward to seeing how the FDA weighs in on the combination. I anticipate that imlunestrant as a monotherapy is going to be a drug that we see being approved.

I was impressed by the imlunestrant side effect data. If this drug gets approved, I think it will be the preferred drug compared to elacestrant. The reason I say that is not because of the efficacy data, because the efficacy was pretty similar across both trials. It’s more because of the toxicities.

Elacestrant is a drug we give in the clinic. The nausea is very real for these patients. Imlunestrant looks like a cleaner drug. That being said, with all of these drugs, we don’t know how they work until they get deployed in the real world. That’s where a lot of you are very helpful. You can raise awareness for certain types of side effects that we either know about or may not get a lot of publicity, but then in later years, we find out that it’s a big deal.

An example of that side effect is inflammation of the lungs from CDK4/6 inhibitors. That was something that didn’t bear out in the phase 3 clinical trials, but it was patient advocates who noticed these side effects. Oncologists noticed these side effects in small numbers. The FDA did a big analysis where they pooled all of this data together and found out that this was actually a safety signal. This is where you all can be very helpful, as these drugs get newly launched into the real world to help us figure out the toxicities.

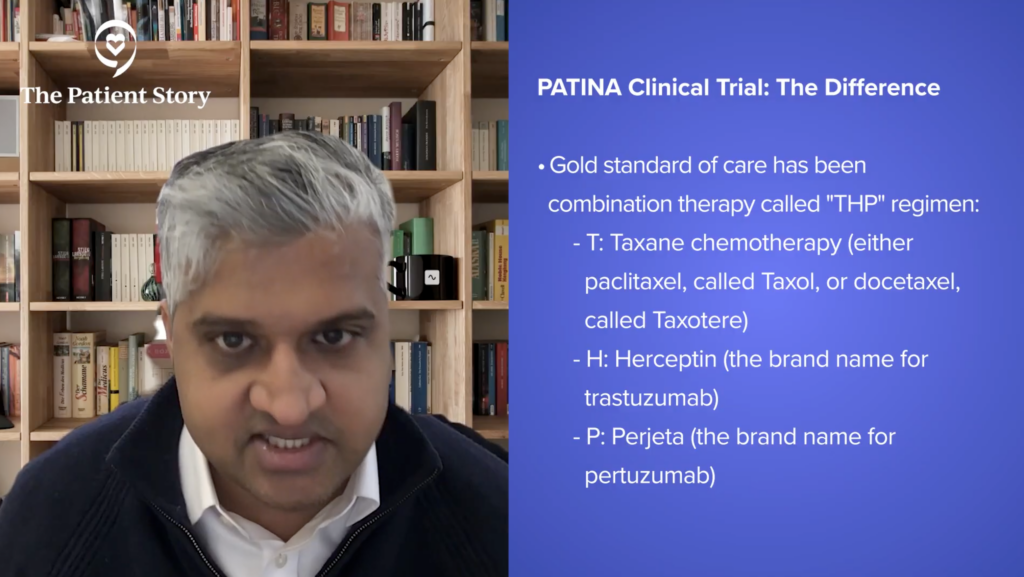

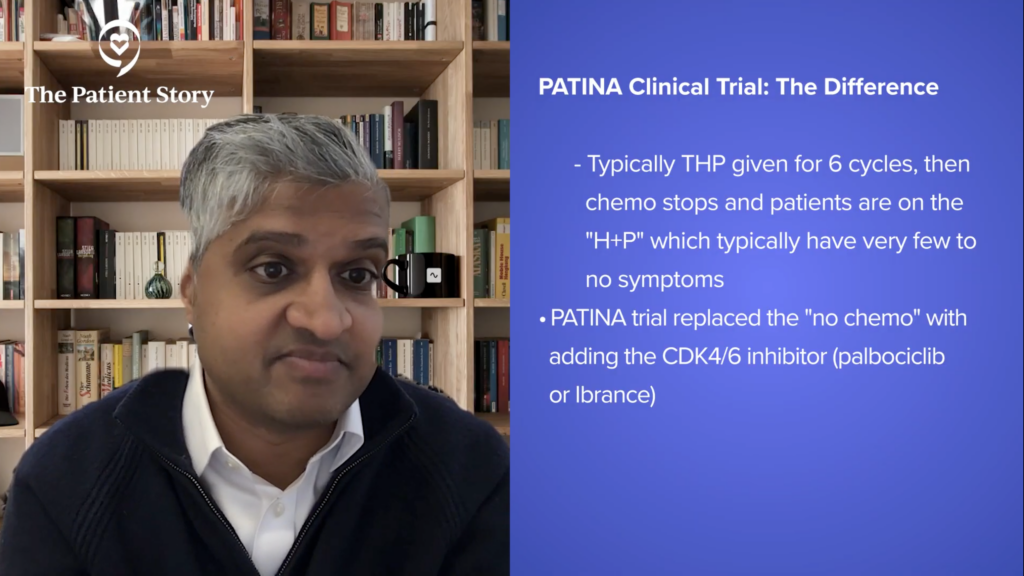

PATINA Clinical Trial

Dr. Vasan: The third trial is PATINA, which is an exciting trial and speaks to the fast-moving pace of this field. This hasn’t been published yet, but it is amazing and groundbreaking. The science is one part of it, but the dissemination of the information is another very important part.

Again, this is where patients can advocate. You want these data as soon as possible. Oncologists have already started to implement these results into clinical practice before the paper has been published.

This trial looked at women with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer who are also ER-positive. HER2-positive breast cancer comprises about 20% of breast cancer and about 70 to 80% of that 20% is estrogen receptor-positive. We sometimes call this triple positive. Generally, we treat these cancers as we treat the HER2 component and then we tack on hormonal therapies in the adjuvant setting and metastatic setting as well.

This trial investigated the addition of CDK4/6 inhibitors, which we know improve overall survival in estrogen receptor-positive, HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer. What about testing it in estrogen receptor-positive, HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer?

It’s a little more complicated because the therapy is a combination of chemotherapy (paclitaxel or docetaxel) with anti-HER2 antibodies trastuzumab and pertuzumab. This is the THP regimen, which is the CLEOPATRA trial. It has been our standard of care for many years now and improves overall survival. It’s the best combination we have in this disease.

They gave the THP therapy. Normally, we give chemotherapy for six cycles, stop chemotherapy, and then patients will be on just trastuzumab and pertuzumab. That’s a great moment in any patient’s disease trajectory and treatment trajectory because once they’re off chemo, the HP (trastuzumab and pertuzumab) has very very few to no side effects.

Patients tell me it’s like getting water. Again, not to minimize anyone who’s had side effects from these drugs, but in large populations, they’re very well tolerated. At that point where we would normally drop the chemo, we would oftentimes add hormone therapy in these patients who are ER-positive, so also adding a CDK4/6 inhibitor, adding palbociclib.

They found that when they did that versus without adding palbociclib, the progression-free survival improvement was gigantic. It went from 29 months to 44 months. One chestnut about this data, if anything, that makes this underappreciated or underrated is the delta or the change between the therapy arms.

You want a big delta. That shows your therapy works. The delta of 12 months is higher than the delta in progression-free survival in ER-positive metastatic breast cancer, meaning that the addition of the CDK4/6 inhibitor is, by these data, maybe even doing more than what we thought it was doing in ER-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer, where CDK4/6 inhibitors transform the landscape.

This is exciting from a therapy point of view. I hope with all my heart that this results in an overall survival improvement. We still need to see, but this is exciting. I think the data blew everyone out of the water. When the progression-free survival curves were shown, there were audible gasps in the audience. We don’t get moments like that a lot and that’s wonderful, so I’m excited about this data.

Taking a big step back, the way that they conducted this trial was interesting because there are other targeted therapies that we use in ER-positive breast cancer, like Akt inhibitors and PI3 kinase inhibitors. PIK3CA is mutated in HER2-positive breast cancer in about 40% of women. Unfortunately, we already know that the antibodies don’t do very well in PIK3CA mutant cancers; antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) seem to do better.

This is an interesting area to start putting in some of these targeted therapies that we only give in ER-positive breast cancer into the ER-positive, HER2-positive space. We’re going to see a lot more trials doing this paradigm.

That’s something for patients who may have ER-positive, HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. This is going to be a very fast-moving area. We’re going to see a lot of trials by many companies and even cooperative groups combining all of these therapies.

There’s still a lot of complexity because you could imagine, this is now going from three drugs to four or five drugs. We have to think about toxicity, but this is incredible data. I was floored when I saw this because I was not expecting it as well. Again, that’s wonderful for all of you.

That’s an interesting example where these important questions that you raise, Abigail, form the hypotheses for clinical trials that are tested rigorously and prospectively, which can help change or guide future treatments.

Abigail: In that context, we know this information, but nothing’s been published yet. Is that correct?

Dr. Vasan: Nothing’s been published yet. Many of us have already started to change our recommendations based on this. Of course, this is a conversation with patients. We have an initial glimpse into the data, but we don’t have all the answers right now. This is such an amazing improvement. We hope that insurance companies and oncologists will advocate for you to try to get this and work their hardest to get this drug if this applies to you. Again, this speaks to the fast-moving nature of this field and how it’s so imperative that we get these results out as soon as we can for everyone.

Abigail: We talk about lines of treatment and how, with each line of treatment, usually you can’t go back once you’ve been on a line of treatment. When we talk about these combinations, is there a concern that we’re potentially taking up two lines of treatment in these triplets? What are your thoughts on that?

Dr. Vasan: Our thoughts on that have evolved. There were discussions five years ago about whether patients whose disease progresses after a CDK4/6 inhibitor in the first-line setting should switch to two different therapies, or if we should keep the CDK4/6 on and change the endocrine therapy, or vice versa. These are studies that have been reported.

We know now that switching the CDK4/6 inhibitor in the second line in large populations of women improves progression-free survival. That’s an interesting example where these important questions that you raise, Abigail, form the hypotheses for clinical trials that are tested rigorously and prospectively, which can help change or guide future treatments.

I do think it’s an important question. With INAVO120, this triplet regimen, you’re using three good drugs all in the beginning. There’s clearly going to be more toxicity, which is also something that has to be dealt with. But is that the best thing to do for these patients? I would argue that the overall survival is positive. We don’t know what the numbers are yet, but that’s a great sign and rationale for why you would want to give all of those drugs.

These are the academic discussions we have as oncologists and with patients as well. Sometimes, there are discussions about adjuvant CDK4/6 inhibitors. We know that these drugs improve disease-free survival. They prevent breast cancer from coming back, but we don’t know if they improve overall survival. They may, but it’s possible that they may not. The trials were not necessarily powered to answer that question. They were smaller trials, so we don’t know.

Should we offer this drug or give this drug? Offering versus giving in shared decision-making are two different issues. Should we be offering this drug to all women who meet these criteria? We don’t know if it helps them live longer. These are questions that we wrestle with every day.

For this triplet therapy, the fact that it improves overall survival is a great win for patients. It’s a complex decision because it adds more side effects in the first-line setting. Normally, patients in the first-line setting are not used to having lots of side effects in general.

Abigail: Thank you for that overview. It can be a little complicated for patients to look at these statistical analyses and graphs. They’re a little Greek to those of us who don’t have that background, so it’s always good to have a doctor interpret. It’s also important to see the evolution of science. We know what we know today, but we’re going to know more tomorrow because of clinical trials and ongoing research.

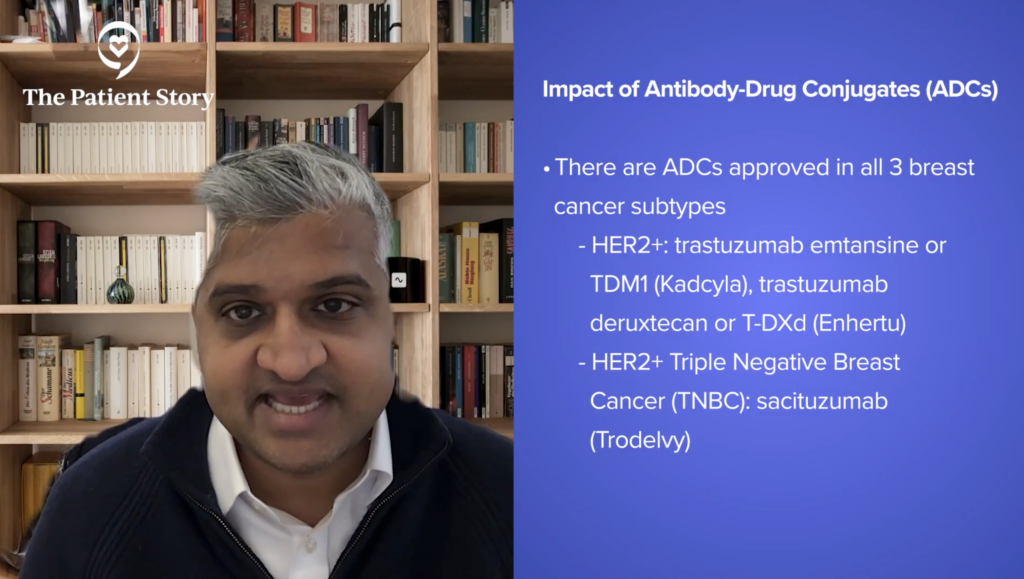

The Impact of Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADCs)

Abigail: You mentioned ADCs. There were some conversations about antibody-drug conjugates and sequencing.

Dr. Vasan: Antibody-drug conjugates have changed the landscape in the treatment of breast cancer. We now have antibody-drug conjugates that are approved in all three subtypes of breast cancer. For HER2-positive, we have trastuzumab emtansine (TDM1) and trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd). For HER2-positive and triple-negative breast cancer, we have sacituzumab.

For HER2-low, which was triple-negative/ER-positive but HER2-low, we have trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd). For ER-positive metastatic breast cancer, we have sacituzumab and datopotamab deruxtecan (Dato-DXd), which is like sacituzumab, a similar target in ER-positive metastatic breast cancer.

In my opinion, it’s always good to have options on the table. I applaud the FDA. As an oncologist, given the data that that’s been shown so far, it’s hard for me to imagine for estrogen receptor-positive metastatic breast cancer recommending Dato-DXd over sacituzumab. This is my opinion, but it is an option, and it may be the best option for you.

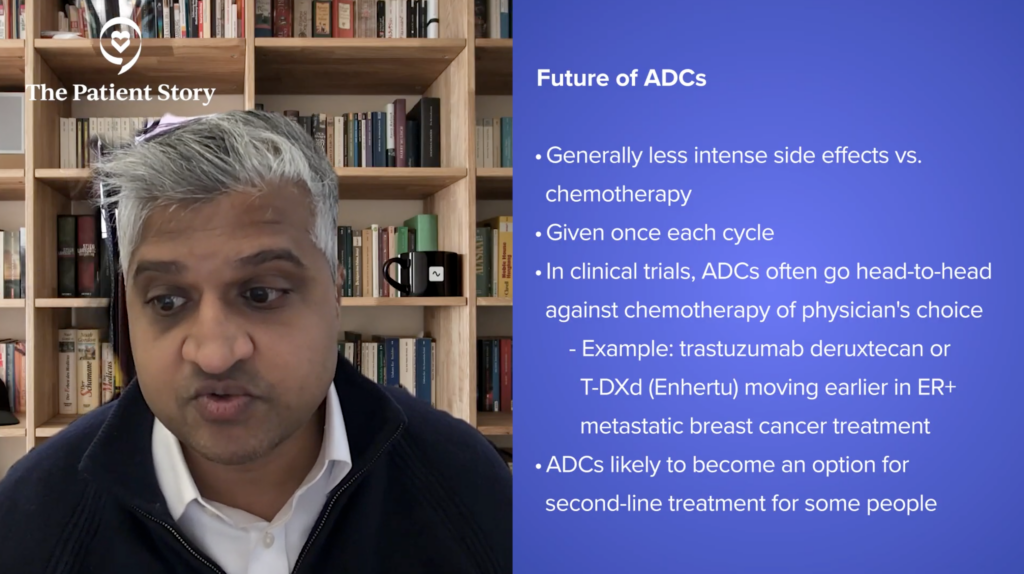

It will be interesting to see how it’s progressed in other breast cancer subtypes and triple-negative breast cancer. It’s being investigated in lung cancer as well. ADCs are here to stay. They’ve changed how we think about drugs and targets. I think about it like next-generation chemotherapy, which is how I communicate it with patients as well.

From my point of view, it’s a helpful metaphor for a couple of reasons. These drugs have side effects that are more similar to chemotherapy. I would argue they’re more muted but similar. And they’re similar in genre. They can cause hair loss, diarrhea, and neuropathy, which are side effects we associate with chemotherapy. Generally, they’re less than what we see with chemotherapy. These drugs are also given in cycles, the same lingo and parlance as chemotherapy. For that purpose, it’s a helpful metaphor.

In the trials testing these drugs, they’re always comparing them to chemotherapy of the physician’s choice. It’s always a head-to-head versus chemo. We’re now seeing T-DXd moving earlier into the neoadjuvant setting and in the ER-positive metastatic breast cancer space. There was an approval for HER2 ultra-low, but it’s moving up.

It’s very likely that soon, with the INAVO120 regimen, if it stops working for those patients, we may be talking about ADCs even in the second-line. These would be patients who are fit and able to tolerate these therapies. That’s a different discussion, but I think that’s where the puck is heading, into the second line. It’s going to be an option. Maybe not for everyone, but it will be an option.

ADCs are changing the game because they’re changing the way we think about toxicity and efficacy, and they’re moving up. More options are always better for patients, but it’s going to be a complicated landscape.

Improving How to Get Medicine to People

Abigail: You’ve talked about toxicities, which is mostly in the context of side effects. What about time toxicity? How do you talk about that with your patients? For example, the difference between taking an oral therapy at home versus going to the infusion center every three weeks for an ADC.

Dr. Vasan: In the HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer space, there has been a lot of emphasis and research on subcutaneous formulations. PHESGO (pertuzumab, trastuzumab, and hyaluronidase-zzxf ) is the drug I’m thinking of, which is given in a shot in the fat. Biosimilars are also a relevant part of the conversation because of cost.

Most of the time, the trastuzumab and pertuzumab that we’re giving in big academic centers are biosimilars now because they’re generic drugs, cheaper, and better for the system. But I do think that this emphasis on the drug getting approved and becoming generic, but with a new formulation, is a very relevant conversation.

This is where your input is very helpful as patients and patient advocates. There may be a world in the distant future where patients, even with metastatic disease, might be taking these drugs at home. I do think that’s a possibility. During the COVID pandemic, when coming into the infusion center was risky for so many patients, those were options that were deployed in trials or feasibility studies. We know it’s possible, feasible, and safe.

Again, this is an area where the puck is moving. Can we come up with better models of getting drugs to patients? The concept of coming in every three weeks versus taking a drug every day have pros and cons. Obviously, a pro about taking an oral pill is that it’s in your control as a patient. You’re taking the medication. It doesn’t necessarily mean that the drug is less toxic. I would argue we have plenty of oral drugs that are more toxic than certain IV chemotherapies. It’s apples versus oranges.

This is where oral SERDs are interesting drugs. We give fulvestrant. Many patients tell us that no one wants to get shots in the buttocks every month. Interestingly, oral SERDs have come along. We thought as a field that oral SERDs were going to replace fulvestrant, but that’s not what we’re seeing because they only seem to have activity in patients whose breast cancers have ESR1 mutations, which is a small piece of the pie.

With every conversation around changing formulations, you have to reinvestigate these questions because some of our assumptions turn out to be wrong. This is an important change in the field. I would even go a step further. Breast cancer has led this in oncology because now we’re starting to see subcutaneous formulations of other antibodies.

These are the things where patients need to be savvy and know everything about what’s going on. If that’s something that gives you solace and lessens your anxiety, these are questions to ask your oncologist. What are the drugs available to me? What are the targeted therapies, antibody-drug conjugates, chemotherapies, antibody therapies, and clinical trials? Which of these drugs are given intravenously? Can we give this in a way that makes more sense for my life? These are all important questions that you should feel empowered to ask because we do have answers.

Abigail: Thank you for bringing up quality of life type discussions and how important it is to have with your doctor.

With obesity, we know that it is a known risk factor for estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer, but less so for other breast cancer subtypes.

Addressing Obesity in the Context of Breast Cancer

Abigail: There was some data that came out at San Antonio about obesity, which is always a sensitive or complicated subject to talk about. How are you having that conversation with your patients, Dr. Vasan?

Dr. Vasan: I’m sure you are aware of the prior Surgeon General’s declaration about multiple cancer types being linked to alcohol intake, and this is important. We’re always interested in trying to find out if there are modifiable risk factors that can decrease the risk of cancer. We know that the warnings on cigarette packs have decreased the rates of lung cancer and the smoking rates are much lower now than they were 20 years ago. But are there other modifiable risk factors that can decrease the risk of breast cancer?

I mentioned obesity in line with alcohol because those two are a little linked. The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) released a concurrent report that argues that if you look at alcohol in the absence of obesity, the risk of breast cancer is a lot lower than we thought. It’s 1% over someone’s lifetime, which is the absolute increase in risk. The relative risk, of course, is higher.

The bottom line is it’s a hard discussion. If there’s a 1% increase in absolute risk, how are you going to decrease that by alcohol cessation, which can be hard and complicated for people? I put that out there.

With obesity, we know that it is a known risk factor for estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer, but less so for other breast cancer subtypes. The way that I talk about it with patients is that this is a modifiable risk factor. If you’re on some sort of active therapy, we’ll put it out on the table and talk about this issue, but we won’t intervene until you’re done with the hardest parts of therapy.

This is something that comes up all the time in the adjuvant setting. It’s natural for women to want to lose weight. You get ambushed with breast cancer, so you want to investigate all the avenues of your life. How can I do better? How can I change things? I always say to patients, “Let’s get through the hardest part. Let’s get through chemotherapy. Let’s get through surgery first. Then, let’s talk about these issues.”

We are starting to see changes in the world of GLP-1s. There’s a lot of interesting work being done looking at these drugs and their anti-cancer effects. These are anti-cancer effects regardless of their effects on diet and weight loss, which is fascinating as well.

This is a fast-moving space. What I recommend to patients is that when we’re talking about weight loss, talk about the real specifics of an exercise regimen and food intake. These are great conversations that are happening in your doctor’s office. This is also something we’re seeing at the national level, even politically. We’re seeing a lot more discussion about lifestyle and changes that can be made.

There’s a lot more awareness now, even in the last couple of years, about what we’re putting into our bodies and our kids’ bodies. The big question is trying to understand if making a change affects your risk of breast cancer. Does that improve your survival with metastatic breast cancer? These are all questions that we’re hoping to find answers to.

They’re very hard studies to design. Certainly, weight loss is going to help anyone, myself included, with all aspects of life: cardiovascular disease, cardiovascular risk factors, etc. But I don’t want someone to become a vegetarian overnight. That’s a pretty drastic change. What’s that going to give you at the end of the day?

These are all important conversations to have, but I do think we’re going to start to see more research done in this area.

Abigail: It’s so important for patients to remember that this isn’t about patient shaming. It isn’t about saying that they’re responsible for anything, but about looking at how to improve the quality of life while reducing risk at the same time. I just wanted to make sure we talked about that.

Editor’s Note: This interview has been edited for clarity and length. This is not medical advice. Please consult with your healthcare provider to make treatment decisions.

The Importance of Understanding Side Effects

Abigail: You were part of a discussion about a case-based clinical approach to ER-positive metastatic breast cancer at one of your presentations in San Antonio. Would you like to talk about that?

Dr. Vasan: ER-positive metastatic breast cancer is a fast-moving field with a lot of new therapies approved within the last two years and with new things in the pipeline. We get into a lot of clinical scenarios. This is very common and happens all the time in the clinic.

Patients who have multiple alterations that we have targetable drugs for, patients who have unusual comorbidities — these are scenarios we see all the time. We’re trying to understand what the best drug is for this patient that will help them live the longest and have the best quality of life. This was a great discussion. It’s wonderful to have a patient advocate on the panel. This is important because a lot of these drugs have side effects that mean different things to different people.

Side effects mean different things to different people. They also mean different things, I would argue, for oncologists compared to patients. The way that we grade and rate side effects can mean a lot of different things. Grade 3 diarrhea is 10 episodes a day, which is insane. Grade 3 is usually the red flag, but grade 1 and grade 2 is still a lot of diarrhea.

Stomatitis is something I think about a lot. It’s a side effect that we’re starting to see more now with Akt inhibitors. There was a reasonable percentage of women who had grade 3 stomatitis, which is inflammation of the mouth. Grade 3 means that stomatitis is so bad that you’re losing weight. Grade 1 means it’s there and grade 2 means it’s painful.

Those are big side effects. You could argue that grade 3 side effect X might be very different from grade 1 side effect Y, if Y is bad. The toxicities and communication of the toxicities are so important to make sure that everyone is on the same page. If you’re having a side effect that you feel is not getting the time that you need to talk about it, you need to talk about it. I always tell my patients, “If something doesn’t feel right, I want to hear from you. I’d rather hear from you than not hear from you.” These are important discussions.

The Importance of Sharing Side Effects with Your Doctor

Abigail: Patients talk about their fear of bringing up a side effect that they’re struggling with because it might mean they can’t stay on the medication. How do you handle that in the clinic?

Dr. Vasan: I always try to make it clear that we have a lot of doses that we can give of drugs. They’re generally for targeted therapies. Patients have multiple options. One of the biggest challenges is trying to communicate that there is no one optimal dose. For whatever reason that we don’t understand, some doses are much better tolerated than others. Certain doses for certain individuals are the perfect range.

It’s very hard to understand and hard to accept. If your doctor recommends a dose reduction, do not equate that with not being as hard enough on yourself or not being as strong. I always tell patients, “I don’t want you to feel the side effects of the therapy. The goal is to see it working on the scans and not have any side effects. That’s not what this is about.”

It’s hard. If I were a patient, I could understand feeling less than if my doctor said I need a lower dose. But I want patients to understand that there’s been so much rigorous analysis of every one of these FDA-approved drugs, looking at lower dose levels, and trying to understand if you are attenuating if you lower the dose. Are you decreasing the benefits of survival, the response rate, etc.? The answer for the vast majority is you’re not, which is so important for patients to understand.

There are a lot of initiatives being done at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) level and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), looking at CDK4/6 inhibitors and changes in doses. Some of these drugs — but not all — are approved in the adjuvant setting. A big reason for that is that some doses were modified, and they used a lower dose in the adjuvant setting.

I want patients to know that doctors are always thinking about this, but that’s a perfect example where it’s baked into how we give the drug. With CDK4/6 inhibitors, we give them three weeks on, one week off. It’s not dose reduction per se — it’s dose intensity — but it’s the same idea. People need to know that if your doctor recommends a lower dose, it’s not because of anything you did or did not do; it’s just because that dose is the right dose for you.

There are a lot of people doing research into pharmacogenomics. There are aspects about different races that may change the way that you metabolize drugs. It’s been known for a very long time that Asians have certain metabolic enzymes that change the way their bodies process capecitabine.

That’s something in the GI (gastrointestinal) cancer field and in certain types of GI cancers, like stomach cancer, that are very prevalent in Asian countries. These are important parts of the conversation. There are biological reasons that we may not know yet that could explain why this dose is not the right dose.

Abigail: Yet another reason why diversity in clinical trials is so important. If we don’t have enough of each group of people, we’re not going to necessarily know if something is specific to that group. Thank you for raising that.

What are You Most Excited About in Breast Cancer Research & Development?

Abigail: What is new and exciting that you’re looking forward to?

Dr. Vasan: I’m very excited about the three trials that I talked about earlier. I think in HER2-positive, T-DXd has already changed the world. There are still many more scenarios that I think T-DXd will find an approved role in. Moving drugs into the neoadjuvant adjuvant setting is always wonderful and I think that’s going to be where that field heads.

The PATINA trial, where we’re starting to integrate targeted therapies into that complicated regimen, is going to be an interesting move that the field heads into.

In estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer, there are still a lot more interesting targets that are being investigated in phase 1 trials. One target I have my eye on is something called KAT6A, an epigenetic target. It’s the idea that your DNA can get modified in lots of different ways. The proteins that modify that DNA are called epigenetic proteins, writers, and erasers. There are lots of different classes and one of those is the protein called KAT6A. It’s going through clinical trials right now. The response rates are very high for patients who have progressed on lots of different therapies. There is also a lot of toxicity, so those will have to be managed.

Mutant-selective PI3 kinase inhibitors are exciting drugs. They seem to have little to no hyperglycemia. They are mutant-selective, so they’re ultra-targeted in a way. They’re only targeting the mutated PI3 kinase in cancer cells and not targeting the normal PI3 kinase in all the other cells in your body, like the liver and fat cells, which can cause all these bad side effects.

Triple-negative breast cancer is still the hardest disease. I do think that some interesting advances are being made in optimizing chemotherapies with immunotherapy. I don’t think we’ve quite cracked that yet. There’s always work being done with BRCA and trying to find the patients who benefit from those therapies.

I think ADCs are going to find a huge traction in TNBC, as they already have. As an example, sacituzumab is a better drug in triple-negative breast cancer than it is in ER-positive breast cancer. There’s still more to be seen there.

I love talking to people who know a lot about breast cancer and people who are outside the field because it’s such a fast-moving field. It’s a privilege to take care of patients who have breast cancer and to be able to talk about all these therapies and communicate. I hope you can tell how excited I am when I talk about this. It’s such an amazing field because everyone is so united and mission-oriented to keep moving faster.

The PIK3CA Pathbreakers Patient Advocacy Group

Abigail: Let’s talk about the patient advocacy group PIK3CA Pathbreakers.

Dr. Vasan: We were inspired by the lung cancer patient advocacy group. There have been targeted therapies for decades now against a slew of genes that are mutated in lung cancer. There have been these incredible groups that have formed around the target. EGFR Resisters is one of them. These amazing groups have changed the world. They have changed patient advocacy. They changed how oncologists think about designing trials. The people in these organizations have seats at the table with pharma companies as they design their trials with regulatory agencies as they’re approving these drugs. It’s incredible.

Breast cancer doesn’t necessarily have a genomically-directed targeted therapy, i.e., a gene that’s mutated that we find on a sequencing report, until PI3 kinase. That’s something that’s lacking in the field.

Abigail and I, together with two other incredible patient advocates, Marlena Murphy, who unfortunately passed away in 2024, and Melanie Sisk, have formed an organization called PIK3CA Pathbreakers. We’re a patient advocacy group formed around patients with PIK3CA-altered breast cancers.

We now have three FDA-approved drugs, two in the last year and a half for this patient population. We’re invested in trying to increase awareness around clinical trials in this space, increase knowledge about side effects through the lens of patients but articulated by oncologists, and try to make sure that we have strategies to mitigate these side effects.

What’s Exciting About Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS)?

Dr. Vasan: The education and landscape around next-generation sequencing have changed dramatically in the last two years. When to get sequencing? What to get sequencing on? How often to get sequencing? These areas are very fast-moving. We’re still trying to make sure that insurance companies are approving these drugs. I do think that these are bigger conversations that we need to have at a national level, but that’s another big area.

What are the mutations? There are thousands of mutations seen in patients. Some are very common, but we get questions all the time about these rare mutations. Do these rare mutations predict response to these drugs? We don’t know.

As an oncologist and someone who specializes in PI3 kinase, I get emails all the time from oncologists all over the country. They see this rare mutation. Does this predict the response for capivasertib? We don’t know.

What are Your Recommended Patient Resources?

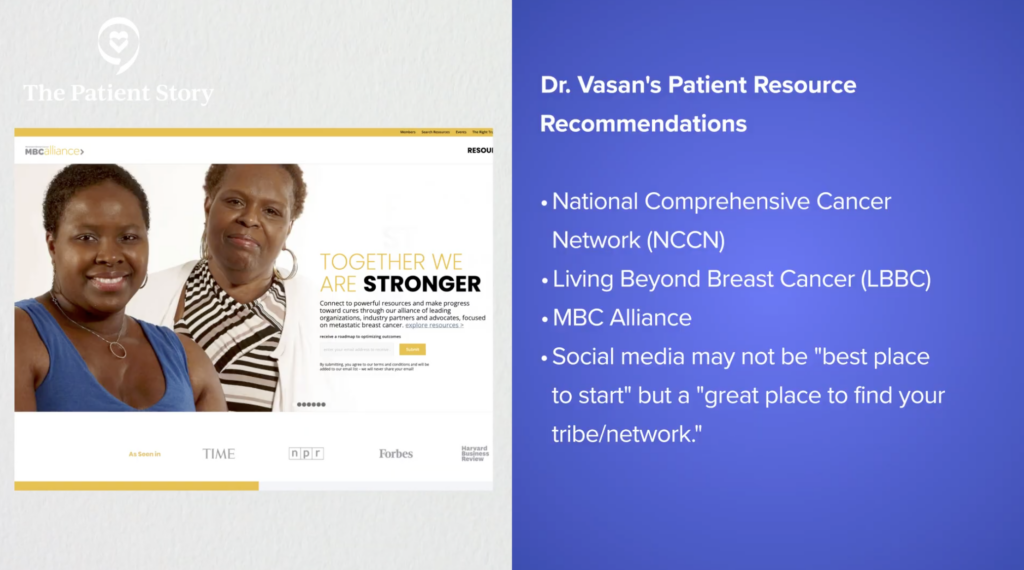

Abigail: Thank you, Dr. Vasan, for your time, your insights, and your excitement. As a patient, it’s always good to see that there are doctors, researchers, and clinicians as invested in our care as we think everybody should be. Very much appreciated. The Patient Story has a YouTube channel with all these videos, which is wonderful. But, Dr. Vasan, where do you point patients to get more information?

Dr. Vasan: Every patient is so different. Sometimes you find something online that’s not right or relevant. Sometimes I hear from patients, “I saw this,” and I have to tell them, “That’s not relevant for you because of X, Y, and Z. It might be something we talk about later, but now, this is why it’s not relevant.”

There can be a lot of information and it’s hard to know how to interpret the data. Breast cancer is such a fast-moving field. When anyone gets diagnosed, they’re going to talk to family members. More often than not, how breast cancer was treated in your loved one five years ago might be radically different. It might not even be an option now because there are newer and better things. It doesn’t mean you should talk to everyone in your life, but you’re going to get a lot of information and sometimes it’s discordant.

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) is a great place to start. The Living Beyond Breast Cancer (LBBC) and MBC Alliance websites are great. All of the documents I’ve seen on all of those websites are spot on. Those are great places to start.

Wikipedia and Twitter are not great places to start. That being said, Twitter is a great place to find your tribe, find your network, and link with people. I highly encourage people to reach out on Twitter. I’ve been humbled and awed by the groundswell in patient advocacy.

The PIK3CA Pathbreakers has a huge Facebook group, as do all of the other patient advocacy groups.

Find your tribe. Get anecdotes and stories from all of those people, but be judicious about what information you take in about your own cancer. Don’t necessarily extrapolate everything you hear to your own.

Conclusion

Abigail: The most important thing that patients who are living with breast cancer and their loved ones need to know is that there’s no one right way to do it. What makes you comfortable, what makes you able to handle it, and what makes you able to put cancer into your life, not your life into cancer — that is the right way to live with cancer.

Metastatic Breast Cancer Patient Stories

Deb O., Breast Cancer (De Novo Triple Positive and ER+ HER-)

Symptoms: First instance: appearance of lump that later on increased in size, orange peel-like skin around inverted nipple, persistent ache under right arm; second instance: appearance of lump

Treatments: First instance: chemotherapy, targeted therapy, hormone therapy; second instance: surgery (mastectomy), chemotherapy, radiation therapy, CDK 4/6 inhibitor

Tammy U., Metastatic Breast Cancer, Stage 4

Symptoms: Severe back pain, right hip pain, left leg pain

Treatments: Surgeries (mastectomy, hip arthroplasty), chemotherapy, radiation therapy, hormone therapy, targeted therapies (CDK4/6 inhibitor, antibody-drug conjugate)

Nicole B., Triple-Negative Metastatic Breast Cancer, Stage 4 (Metastatic)

Symptoms: Appearance of lumps in breast and liver, electric shock-like sensations in breast, fatigue

Treatments: Chemotherapy, surgeries (installation of chemotherapy port, mastectomy with flat aesthetic closure), targeted therapy (antibody-drug conjugate), hyperbaric oxygen therapy, lymphatic drainage

Dalitso N., IDC, Stage 4, HER+

Symptoms: Appearance of large tumor in left breast, severe back and body pain

Treatments: Surgery (hysterectomy), vertebroplasty, radiation therapy, hormone therapy, clinical trial

Marissa T., ILC, Stage 4, BRCA2+

Symptoms: Appearance of lump in right breast, significant fatigue, hot flashes at night, leg restlessness leading to sudden, unexpected leg muscle cramps

Treatments: Chemotherapy, hormone therapy, PARP inhibitor, integrative medicine

Janice C., Triple-Negative Metastatic Breast Cancer, Stage 4

Symptoms: Appearance of lump in left breast near sternum, fatigue, bone and joint pain

Treatments: Surgery (lumpectomy), radiation therapy (brachytherapy), chemotherapy

Dana S., IDC, Stage 4 (Metastatic)

Symptom: Appearance of large lump in left armpit

Treatments: Targeted therapy, hormone blockers, bone infusions

Maria S., Breast Cancer, Stage 4

Symptoms: Intermittent but severe pain including a burning sensation on the side of the breast, appearance of a cyst and a lump, abnormally warm and pink-colored breast, nipple inversion, strangely liquid menstrual periods, unusual underarm odor, darkening and dimpling of the nipple, severe fatigue, night sweats

Treatments: Chemotherapy, surgeries (mastectomy, lymphadenectomy), radiation therapy, targeted therapy

- 1

- 2